Abstract

Objective:

Adolescents are exposed to alcohol marketing through traditional advertising and through newer digital media channels. Cumulative marketing exposure across channels is of concern but has been insufficiently studied. This study explores the measurement of alcohol marketing exposure across channels and whether cumulative recalled exposure is independently associated with underage drinking.

Method:

Two hundred two New England adolescents (ages 12–17 years) were recruited from a general pediatrics clinic and completed an online survey. Recall of alcohol marketing across channels (e.g., Internet, magazines) was assessed, along with drinking behavior and relevant covariates (i.e., demographics, parental/peer drinking, smoking status, sensation seeking, Internet use, social media use, television use, and parental Internet monitoring). Confirmatory factor analysis was used to establish a latent construct of alcohol marketing exposure recall. Logistic regression tested associations between alcohol marketing recall and adolescent drinking, with covariates controlled for.

Results:

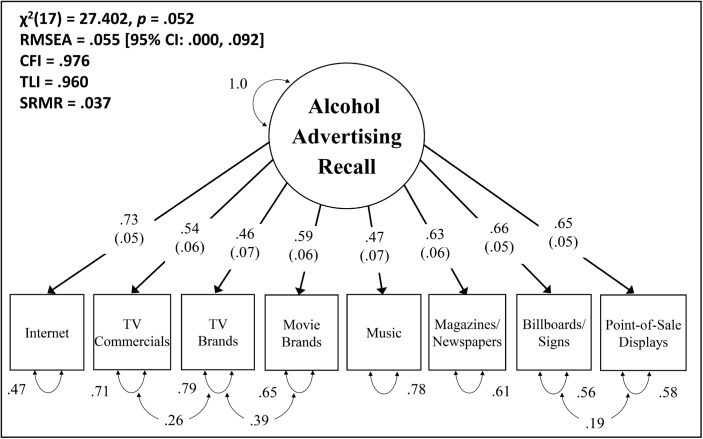

Adolescents reported recall of alcohol marketing across all marketing channels. Alcohol marketing recall items were significantly correlated, with α = .83. The latent measurement model of alcohol marketing recall provided excellent fit to the data, χ2(17, n = 202) = 27.402, p = .052; root mean square error of approximation (.000–.092) = .055; Tucker–Lewis Index = .960; comparative fit index = .976; standardized root mean square residual = .037). Adjusted cross-sectional logistic regression analyses demonstrated that the latent alcohol marketing recall construct was significantly associated with underage drinking (adjusted odds ratio = 4.08, 95% CI [1.15, 14.46]) when relevant covariates were accounted for.

Conclusions:

The final measurement model provided support for construct validity of a novel alcohol marketing recall construct assessing cumulative cross-channel marketing exposure. Adolescent recall of alcohol marketing across channels was significantly associated with underage drinking, while associated factors such as peer/parental drinking were accounted for.

Exposure to alcohol advertisements is predictive of adolescent drinking initiation and of progression to problematic drinking behaviors, as demonstrated across multiple cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Anderson et al., 2009; Jackson et al., 2018; Jernigan et al., 2017). These findings have been replicated when assessing advertising exposure within and across various media exposures, such as advertising or brand placement within movies and television content (Koordeman et al., 2012), in television commercials (Ross et al., 2015; Stacy et al., 2004), in music (Primack et al., 2014), in point-of-sale advertising, and via the Internet (McClure et al., 2019). Hereafter, channel refers to any of these or other specific outlets of media exposure through which marketing can be disseminated. Adolescent consumption of media is inherently cross channel, as teens continue to report a high use of media through a variety of channels as part of their daily activities.

Recently, industry marketing practices have seen rapid evolution with the proliferation of social media and Internet channels that allow for marketing campaigns to appear across more traditional media (magazine, newspaper, billboard, radio) as well as these newer digital channels (Jernigan & Rushman, 2014). With these new media/digital marketing campaigns, messages can be reinforced in multiple settings such as social media, gaming, and entertainment websites, many of which include online peer networking (Jackson et al., 2018). The evolving digital environment extends the opportunities for dissemination and engagement beyond traditional types of marketing (e.g., television commercials) and has greater potential to reach and influence underage audiences, including large numbers of adolescents who live in digitally integrated environments with easy access to multiple forms of media (Jernigan & Rushman, 2014).

Of particular concern is the marketing of products that introduce health risks to adolescents such as tobacco, alcohol, and calorie-dense nutrient-poor foods. Traditional media channels (e.g., movies and television) have frequently depicted content including adolescent alcohol consumption or product placement of alcohol (Roberts et al., 2016; Sargent et al., 2006; Siegel et al., 2016), as well as delivering more traditional advertising. Advancements in technology such as directed advertising on Internet-connected devices provide potential for multiple sources of exposure through a single device (e.g., Internet ads and television and movie content all consumed on a smartphone device), including a more interactive approach, potentially enabling greater engagement and impact (McClure et al., 2016, 2019). Indeed, there is growing evidence that adolescents are exposed to and influenced by online alcohol marketing (Hoffman et al., 2014; Jernigan, 2012; Jones & Magee, 2011; Leyshon, 2011; McClure et al., 2016; Montgomery et al., 2012), despite self-regulation of marketing by the alcohol industry (Federal Trade Commission, 2014). Thus, youth are encountering a greater variety of exposures to depictions of alcohol across a larger number of media channels that accumulates and has concerning behavioral implications.

A substantial literature exists on the influence of single-channel exposure to media depictions of alcohol on youth development of drinking behavior (Anderson et al., 2009; Jackson et al., 2018; Jernigan et al., 2017). For example, Sargent and colleagues have published numerous studies on depictions of alcohol in movies and the prospective association with youth alcohol use initiation and progression to binge drinking (Dal Cin et al., 2009; Sargent et al., 2006). Several researchers have studied the effects of exposure to alcohol television advertisements on youth drinking behavior (Jernigan et al., 2013; Morgenstern et al., 2014). Some work has also been done in other media channels such as music (Primack et al., 2014) and magazines (Ross et al., 2014b).

More recently, in recognition of the multichannel marketing campaigns used by the alcohol industry, researchers have begun to assess alcohol marketing exposure in youth across channels. For example, Gordon and colleagues conducted a study of prompted recall of alcohol marketing across 15 different media channels (e.g., television/cinema, billboards, sports-related sponsorship, celebrity endorsements) in youth between ages 12 and 14 years (Gordon et al., 2010). In a European study on alcohol marketing exposure and drinking behavior, researchers created a latent variable across 13 different marketing channels, which served as a predictor of drinking onset and progression to binge drinking across time (de Bruijn et al., 2016). Of note, this study tested reciprocal effects of drinking on marketing exposure recall as well and did not find significant prospective pathways between drinking behaviors and subsequent alcohol marketing recall.

Several explanatory models have been put forth to provide a rationale for the link between media/marketing exposures and the development of subsequent risk behaviors such as smoking and alcohol use (Jackson et al., 2018). For example, Social Learning Theory assumes that people have the capacity to learn by observation, enabling acquisition of large, integrated patterns of behavior. Applied to media exposure and alcohol use, drinking behavior can be reinforced when viewers see that engagement in drinking by media characters is followed by social rewards (e.g., having fun or getting more attention from romantic partners; Bandura, 1977, 2001).

Relatedly, the Message Interpretation Process (MIP) model suggests that individuals participate in their socialization process by making decisions based, in part, on information from media messages. The MIP model holds that individuals use both logical and affective strategies to interpret messages, which contribute to belief formation as an individual either internalizes or rejects messages received (Austin, 2007).

Aligned with MIP and specific to alcohol marketing, the Alcohol Marketing Receptivity model (McClure et al., 2013) provides a framework of explanatory developmental cascade for adolescent progression from nondrinker to drinker as engagement with alcohol marketing increases over time. This model suggests that adolescent exposure to alcohol marketing influences alcohol-related attitudes/expectancies and future attention to marketing (Austin et al., 2006; Morgenstern et al., 2011; Russell et al., 2014). Then, as marketing preferences develop, adolescent recognition of and affiliation with alcohol brands occurs, impacting their identities related to drinking (Lin et al., 2012). Across these models, a unifying theme emerges in which greater exposure to alcohol use and marketing, as well as interactivity of marketing messages, would relate to increased risk for drinking behavior, and that broad and cumulative exposure would have more of an impact.

As marketing approaches have shifted with the changes in technology, so must our research approach shift to include more comprehensive measurement of advertising exposure. Specifically, we need new methods to account for the complexity of adolescent exposure to marketing across different channels (e.g., movies, Internet, billboards). As described above, most of the literature in this area has used a single channel of marketing exposure such as movies (Dal Cin et al., 2008) or television (Ross et al., 2014a) or music (Primack et al., 2014). However, youth use diverse media consumption habits, and assessment of just one domain of media consumption likely underestimates youth exposure to media depictions of alcohol and to integrated marketing campaigns. A method of capturing marketing exposure across marketing channels is needed to provide more information about the depth and breadth of marketing exposures, and to better understand the influence of this exposure on youth behavior.

The present study seeks to extend the literature on adolescent media alcohol exposures by exploring and evaluating a more comprehensive approach to the measurement of adolescent exposure, across different marketing channels. Given the shift in media dissemination with the rise of digital technology, our first aim was to describe exposures to alcohol marketing that may occur across a range of channels, with distinction between digital media channels (e.g., Internet, social media, and including movies and television) and exposures that occur in built/print channels (e.g., billboards, magazines). Second, we explored the potential of creating a cumulative measure of adolescent alcohol marketing exposure across channels through latent modeling. Last, we tested the association between this latent construct of cumulative recalled alcohol marketing exposure across channels and adolescent drinking to determine whether the latent model approach offers additional information beyond the assessment of a single form of exposure. These findings are intended to be a first step in defining a more comprehensive measurement approach as a means to inform future longitudinal studies that can explore predictive associations more fully.

Method

Recruitment and survey methods

A convenience sample of 202 adolescents ages 12–17 years was recruited from a general pediatric clinic in New England, using an electronic medical record–based telephone recruitment protocol. Between December 2015 and October 2016, eligible adolescents were identified through a partial HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996) waiver and were contacted by phone. Recruiters obtained verbal parental permission and collected basic demographic information, then obtained child assent before directing adolescents to a web portal to complete the survey of adolescent media and marketing exposure. Participants were given a unique username and password to ensure confidentiality. An encrypted electronic database was used for recruitment, tracking, and data management. The Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth College approved the study.

Measures

Outcome.

Any lifetime drinking was assessed with the item “Have you ever had a drink of alcohol, other than a few sips?” (yes, no).

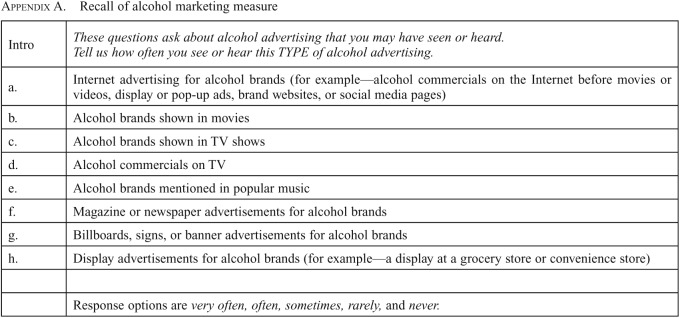

Recall of Alcohol Marketing measure.

To assess exposure across channels, the Recall of Alcohol Marketing measure provided three alcohol marketing recall scores, derived from a single multiresponse variable assessing recalled exposure to various types of alcohol marketing that had been used in prior single-exposure studies (e.g., Dal Cin et al., 2008; see Appendix A at the end of the article). Total recall of alcohol marketing was derived from survey items that asked, “Tell us how often you see or hear this type of alcohol advertising” (very often, often, sometimes, rarely, or never; eight items; Cronbach’s α = .83). Marketing recall was then divided into two scores. The first was a built/print marketing score (three items assessing participants’ recall of alcohol marketing in their physical environment: “Magazines or newspaper advertisements for alcohol brands,” “Billboards, signs, or banner advertisements for alcohol brands,” and “Display advertisements for alcohol brands [for example—a display at a grocery or convenience store]”; Cronbach’s α = .70). The second was a digital marketing score (five items assessing participants’ recall of alcohol marketing from broadcast or Internet sources: “Alcohol commercials on TV,” “Alcohol brands shown in TV shows,” “Alcohol brands shown in movies,” “Internet advertising for alcohol brands [for example—alcohol commercials on the Internet before movies or videos, display or pop-up ads, brand websites or social media pages, etc.],” and “Alcohol brands mentioned in popular music”; Cronbach’s α = .74).

Covariates.

Covariates identified by prior research that might influence the association between alcohol marketing exposure and adolescent drinking were assessed within the regression analysis. Sociodemographics included age, gender, race (dichotomized at the analytic phase to White and non-White because of very small minority numbers), and parental education. Adolescent characteristics included smoking status (ever/never) and sensation-seeking propensity, based on a six-item scale (α = .74) that included agreement with statements such as “I like to do frightening things” or “I like to explore strange places.”

In addition, a number of media variables were included to control for general media use by adolescents as well as monitoring by parents. Television time was assessed by asking, “On [weekdays/weekends], how many hours a day do you watch TV?” (none, ½ hour/day, 1 hour/day, 2 hours/day, 3 hours/day, 4 hours/day, 5 or more hours/day). A sum score for television time was calculated across weekends/weekdays and was used in the regression model. Two Internet time variables, weekday Internet time and weekend Internet time, were used to assess recreational use: “On [weekdays/weekends], how many hours a day do you use the Internet for personal use, like shopping, reading the news, playing games, checking personal email, or social networking?” (none, ½ hour/day, 1 hour/day, 2 hours/day, 3 hours/day, 4 hours/day, 5 or more hours/day). Sum scores for television time and Internet time were calculated across weekends/ weekdays and were used in the regression model. Last, the frequency of social media use was assessed with “How often do you use social media?” (never, rarely, once in a while, about once a day, many times a day).

Additional peer and family covariates identified in prior research on marketing and youth drinking included friend/parental alcohol use, parental monitoring, and parental responsiveness. Peer drinking was assessed by asking, “How many of your friends drink alcohol? Would you say . . . none, a few, more than a few, most?” and parental drinking by asking, “Which of the following statements best describes how often your mother/father drinks alcohol? Would you say . . . never, occasionally, weekly, daily?” For parental drinking, if drinking by two parents was reported, the higher parental report was included. Parental monitoring was indicated by items such as “How often does your parent know where you are and what you are doing after school?” (six items; α = .70) and parental responsiveness indicated by items such as “How often does a parent let you know he/she really cares about you?” (four items; α = .90).

Statistical analysis

We first examined distributions of and correlations between all variables of interest. T-tests were used for continuous variables to determine differences across adolescent recall of alcohol marketing across built/print versus digital environments. To examine the structure of the latent alcohol marketing recall construct, confirmatory factor analysis was used within a structural equation modeling framework to assess the measurement model. Factor loadings were examined to determine the relative strength and the significance of influence on the latent construct. A “good” fitting model provides a structure that is relatively consistent with the data and is estimated using a number of different fit indices. Model fit was estimated using practical fit indices such as the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the nonnormed fit or Tucker–Lewis index (TLI). Acceptable levels for these fit indices are greater than .90 for CFI and TLI and lower than .08 for RMSEA and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR; Browne, 1993; MacCallum et al., 1996). Once the measurement model for the latent alcohol marketing recall construct was established, cross-sectional logistic regression identified associations between the latent alcohol marketing construct across venues and underage drinking, while the above listed covariates were controlled for. Missingness was minimal (<5% missing across all variables). However, multiple imputation with the expectation-maximization algorithm was used to mitigate bias, which resulted in 100 imputed data sets. All models were run using Mplus Version 7.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 2013).

Results

Sample description

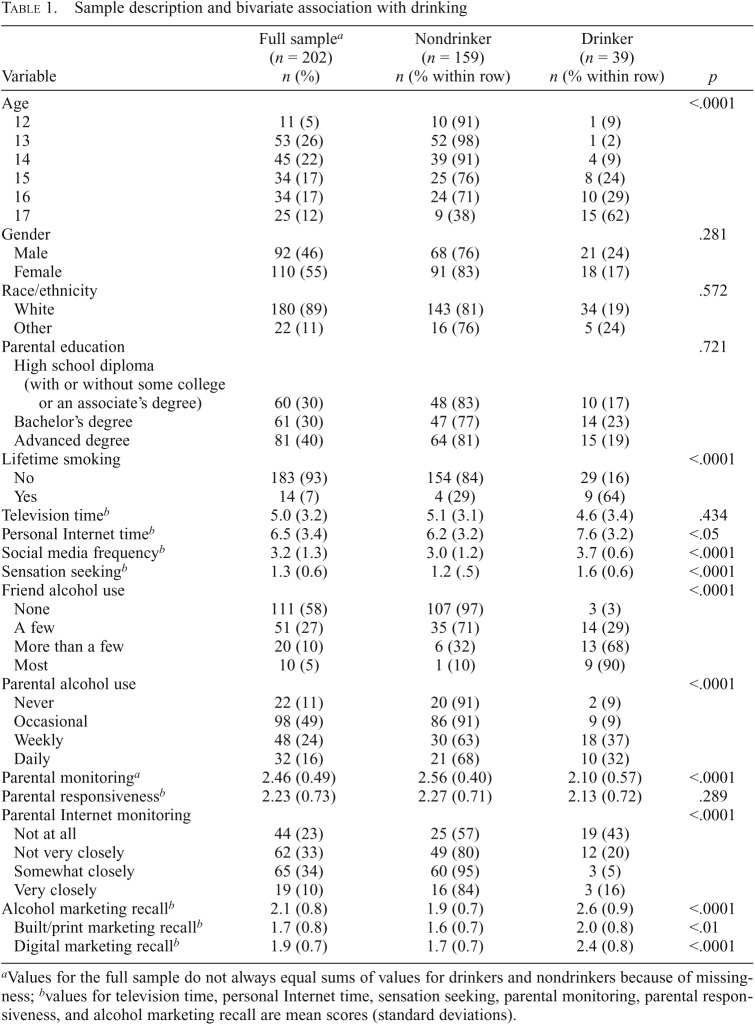

The sample (n = 202) ranged in age from 12 to 17 years (M = 14.5 years, SD = 1.48) and was equally distributed by gender (55% female). The majority (89%) of participants identified as White, with highly educated parents. Of participants, 40% reported that they had a parent who drank weekly to daily, and a little under half (42%) reported having friends who drink. Smoking prevalence in the sample was 7%, and 20% of participants reported a history of ever drinking. See Table 1 for additional demographic information.

Table 1.

Sample description and bivariate association with drinking

| Variable | Full samplea (n = 202) n (%) | Nondrinker (n = 159) n (% within row) | Drinker (n = 39) n (% within row) | p |

| Age | <.0001 | |||

| 12 | 11 (5) | 10 (91) | 1 (9) | |

| 13 | 53 (26) | 52 (98) | 1 (2) | |

| 14 | 45 (22) | 39 (91) | 4 (9) | |

| 15 | 34 (17) | 25 (76) | 8 (24) | |

| 16 | 34 (17) | 24 (71) | 10 (29) | |

| 17 | 25 (12) | 9 (38) | 15 (62) | |

| Gender | .281 | |||

| Male | 92 (46) | 68 (76) | 21 (24) | |

| Female | 110 (55) | 91 (83) | 18 (17) | |

| Race/ethnicity | .572 | |||

| White | 180 (89) | 143 (81) | 34 (19) | |

| Other | 22 (11) | 16 (76) | 5 (24) | |

| Parental education | .721 | |||

| High school diploma (with or without some college or an associate’s degree) | 60 (30) | 48 (83) | 10 (17) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 61 (30) | 47 (77) | 14 (23) | |

| Advanced degree | 81 (40) | 64 (81) | 15 (19) | |

| Lifetime smoking | <.0001 | |||

| No | 183 (93) | 154 (84) | 29 (16) | |

| Yes | 14 (7) | 4 (29) | 9 (64) | |

| Television timeb | 5.0 (3.2) | 5.1 (3.1) | 4.6 (3.4) | .434 |

| Personal Internet timeb | 6.5 (3.4) | 6.2 (3.2) | 7.6 (3.2) | <.05 |

| Social media frequencyb | 3.2 (1.3) | 3.0 (1.2) | 3.7 (0.6) | <.0001 |

| Sensation seekingb | 1.3 (0.6) | 1.2 (.5) | 1.6 (0.6) | <.0001 |

| Friend alcohol use | <.0001 | |||

| None | 111 (58) | 107 (97) | 3 (3) | |

| A few | 51 (27) | 35 (71) | 14 (29) | |

| More than a few | 20 (10) | 6 (32) | 13 (68) | |

| Most | 10 (5) | 1 (10) | 9 (90) | |

| Parental alcohol use | <.0001 | |||

| Never | 22 (11) | 20 (91) | 2 (9) | |

| Occasional | 98 (49) | 86 (91) | 9 (9) | |

| Weekly | 48 (24) | 30 (63) | 18 (37) | |

| Daily | 32 (16) | 21 (68) | 10 (32) | |

| Parental monitoringa | 2.46 (0.49) | 2.56 (0.40) | 2.10 (0.57) | <.0001 |

| Parental responsivenessb | 2.23 (0.73) | 2.27 (0.71) | 2.13 (0.72) | .289 |

| Parental Internet monitoring | <.0001 | |||

| Not at all | 44 (23) | 25 (57) | 19 (43) | |

| Not very closely | 62 (33) | 49 (80) | 12 (20) | |

| Somewhat closely | 65 (34) | 60 (95) | 3 (5) | |

| Very closely | 19 (10) | 16 (84) | 3 (16) | |

| Alcohol marketing recallb | 2.1 (0.8) | 1.9 (0.7) | 2.6 (0.9) | <.0001 |

| Built/print marketing recallb | 1.7 (0.8) | 1.6 (0.7) | 2.0 (0.8) | <.01 |

| Digital marketing recallb | 1.9 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.8) | <.0001 |

Values for the full sample do not always equal sums of values for drinkers and nondrinkers because of missingness;

values for television time, personal Internet time, sensation seeking, parental monitoring, parental responsiveness, and alcohol marketing recall are mean scores (standard deviations).

Recall of alcohol marketing: Built/print versus digital marketing

Most adolescents reported seeing alcohol advertisements at least “sometimes” across each of the digital marketing channels (i.e., 55% on the Internet, 60% in music, 69% in movies, 63% in television shows, and 71% in television advertisements). Across built/print channels, most adolescents recalled in-store display advertisements at least “sometimes” (73%), and approximately half reported recall at least “sometimes” on billboards or banner advertisements (47%) and in magazines or newspapers (50%).

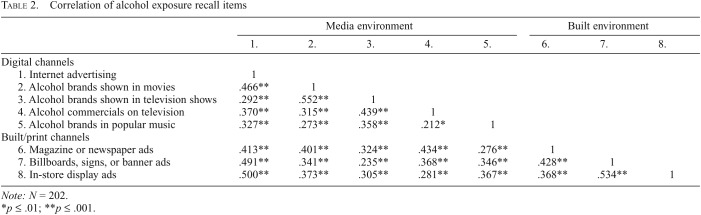

The average/mean total alcohol marketing recall score was 1.79 (SD = 0.70). Participants had significantly greater recall scores for alcohol marketing from digital media channels (M = 1.88, SD = 0.73) compared with built/print sources (M = 1.68, SD = 0.82) (t = 3.78, p < .001). However, alcohol marketing recall scores across these two sources were significantly correlated at r = .66 (p < .001), with a positive linear association based on inspection of a scatter plot. All assessed marketing channels were significantly correlated with each other (as shown in Table 2), which is supportive of a single-factor latent model.

Table 2.

Correlation of alcohol exposure recall items

| Media environment |

Built environment |

|||||||

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | |

| Digital channels | ||||||||

| 1. Internet advertising | 1 | |||||||

| 2. Alcohol brands shown in movies | .466** | 1 | s | |||||

| 3. Alcohol brands shown in television shows | .292** | .552** | 1 | |||||

| 4. Alcohol commercials on television | .370** | .315** | .439** | 1 | ||||

| 5. Alcohol brands in popular music | .327** | .273** | .358** | .212* | 1 | |||

| Built/print channels | ||||||||

| 6. Magazine or newspaper ads | .413** | .401** | .324** | .434** | .276** | 1 | ||

| 7. Billboards, signs, or banner ads | .491** | .341** | .235** | .368** | .346** | .428** | 1 | |

| 8. In-store display ads | .500** | .373** | .305** | .281** | .367** | .368** | .534** | 1 |

Note: N = 202.

p ≤ .01; **p ≤ .001.

Latent construct of recall of alcohol marketing

All indicators for the latent alcohol marketing recall construct were significantly correlated at the p < .01 level (Table 2). Examination of the measurement model of the latent alcohol marketing recall construct with no correlated residuals provided poor fit to the data, χ2(20, n = 202) = 69.64, p < .001; RMSEA (.083–.140) = .111; TLI = .837; CFI = .884; SRMR = .058. Based on theory, examination of the correlation matrix, and information provided through modification indices, residuals were correlated across television commercials and television brand placement, across brand placement in television and in movies, and across billboards/signs/banner ads and in-store display ads for alcohol brands. The final measurement model of the alcohol marketing recall construct identified in Figure 1 demonstrated excellent fit, χ2(17, n = 202) = 27.402, p = .052; RMSEA (.000–0.092) = .055; TLI = .960; CFI = .976; SRMR = .037. A model examining a two-factor solution (built/print vs. digital channels) was tested but did not provide improved fit to the data and demonstrated a linear dependency between the two constructs, with the latent correlation between constructs not significantly differing from 1; thus, the one-factor solution was used in the regression model.

Figure 1.

Measurement model of the latent alcohol advertising recall construct. RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CI = confidence interval; CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker–Lewis index; SRMR = standardized root mean square residual.

Association between cross-channel recall of alcohol marketing and drinking

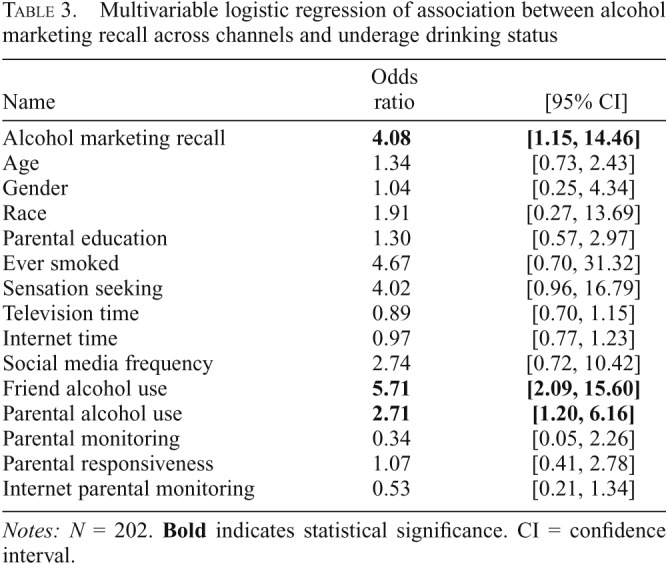

In a cross-sectional logistic regression model predicting underage drinking status, we found that the latent alcohol advertising recall construct was significantly associated with adolescent drinking status (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 4.08, 95% CI [1.15, 14.46]), while accounting for relevant covariates (Table 3). Friend alcohol use (AOR = 5.71, 95% CI [2.09, 15.60]) and parental alcohol use (AOR =2.71, 95% CI [1.20, 6.16]) were the only covariates that retained significance in the final model, although sensation seeking trended toward significance as well (AOR = 4.02, 95% CI [0.96, 16.79]). The only correlated residuals that retained significance with alcohol marketing recall were age (β = .291, p < .01) and social media frequency (β = .408, p < .001).

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression of association between alcohol marketing recall across channels and underage drinking status

| Name | Odds ratio | [95% CI] |

| Alcohol marketing recall | 4.08 | [1.15, 14.46] |

| Age | 1.34 | [0.73, 2.43] |

| Gender | 1.04 | [0.25, 4.34] |

| Race | 1.91 | [0.27, 13.69] |

| Parental education | 1.30 | [0.57, 2.97] |

| Ever smoked | 4.67 | [0.70, 31.32] |

| Sensation seeking | 4.02 | [0.96, 16.79] |

| Television time | 0.89 | [0.70, 1.15] |

| Internet time | 0.97 | [0.77, 1.23] |

| Social media frequency | 2.74 | [0.72, 10.42] |

| Friend alcohol use | 5.71 | [2.09, 15.60] |

| Parental alcohol use | 2.71 | [1.20, 6.16] |

| Parental monitoring | 0.34 | [0.05, 2.26] |

| Parental responsiveness | 1.07 | [0.41, 2.78] |

| Internet parental monitoring | 0.53 | [0.21, 1.34] |

Notes: N = 202. Bold indicates statistical significance. CI = confidence interval.

Discussion

Adolescents today are confronted with integrated alcohol marketing campaigns that include marketing across a range of channels, including built/print and a broad range of digital environments. Prior research has demonstrated a link between alcohol marketing exposure within specific channels (e.g., movies or television advertisements), but little work had been done to examine the potential cumulative impact of marketing exposure across multiple channels. The present study extends the prior literature by assessing adolescent recall of alcohol marketing across multiple channels through the use of multiple indicators and latent modeling. The proposed measurement model in this study demonstrates that a latent construct of adolescent recall of alcohol marketing across channels can be determined and has good fit to our model. Furthermore, the high association between built/print and digital channel exposures suggests that adolescents report exposures across multiple channels and that higher within-adolescent exposure co-occurs across both settings. Given that the one-factor model appeared to provide a more parsimonious fit to the data than a two-factor model (separating built/print vs. digital marketing recall) without substantial loss of information, it may be more appropriate to consider the cumulative impact of marketing across channels; this approach is more aligned with industry use of integrated marketing campaigns. Crucially, we found that this model of adolescent recall of alcohol marketing was significantly associated with underage drinking, while accounting for the influence of 14 other covariates. Despite our small sample, this is suggestive of a robust and independent association between recall of marketing and drinking behavior and one that is equivalent in magnitude to other known risk factors such as peer drinking.

As media and technology advance and offer new avenues for industry marketing, the measurement of youth exposure to marketing becomes more complex. Of particular public health concern is the growing influence of marketing that occurs in digital media environments such as social media or other Internet sources, as well as within online streaming of television and movie content. Digital media environments offer ways for adolescents to engage with marketing campaigns more actively, through tools such as Advergames or interactions with brand sites, or posting of their own alcohol-related content in online peer networks. These extensions beyond traditional forms of media marketing have created a media environment for young people that is particularly challenging for parents to monitor and restrict. It is therefore not surprising that, within this sample, adolescents recalled a higher frequency of alcohol marketing within digital channels compared with built/print channels. This could represent higher levels of actual marketing exposure, or it could indicate that media venues provide more salient or memorable types of marketing exposure for adolescents. This finding is consistent with a recent study by Jernigan and colleagues (2017), which demonstrated greater exposure to marketing through the Internet and television than from billboards.

Results should be considered in the context of limitations inherent within the study. First, this regional New England sample was small and sociodemographically homogeneous. Despite this, a strong latent measurement model of alcohol advertising recall was obtained and demonstrated significant associations with underage drinking. Second, although the models tested included numerous covariates identified as influential for adolescent drinking outcomes, it is possible that an unmeasured confounder could explain the identified association between adolescent recall of marketing and adolescent drinking initiation. Third, given the rapid change of new media technology, a single item measuring “Internet” alcohol recall may not be as informative, because multiple items assess recall across Internet channels as well (e.g., social media, YouTube). This study also assessed a “lifetime” measure of alcohol use, which could have captured youth use that occurred well before the time of the study. Similarly, no time reference for recall of alcohol marketing was provided to participants, and could be considered as an addition in future research.

Last, analyses were cross sectional in nature. Therefore, we cannot assess prospective associations that may be reciprocal with drinking status being predictive of adolescent alcohol marketing recall. Adolescents at higher risk for drinking may seek out media or environments with higher levels of alcohol marketing. Although such reciprocal relations between marketing receptivity and early drinking behaviors are plausible, other work has shown weaker prospective associations between drinking and subsequent exposure to alcohol content in the media than the converse (de Bruijn et al., 2016; Janssen et al., 2018).

Future research using more comprehensive measurements of cross-channel alcohol marketing within larger, more nationally representative prospective samples are indicated to promote better understanding of how adolescent marketing receptivity develops over time and the directionality between these factors. Specifically exploring different types of marketing content, the role of emotional appeals, saliency, and examination of brand placements within media content would further elucidate the nuances associated with alcohol marketing exposure and youth drinking behaviors.

Conclusion

Adolescents consume high amounts of media across a range of channels, which increases the likelihood of exposure to alcohol marketing, a known risk factor for underage drinking initiation and progression. In this study, a latent construct of adolescent recall of alcohol marketing across channels was established that could be used in future studies as a more robust predictor of adolescent drinking status than single-channel marketing recall. Given the breadth of prior research on each of these marketing channels, as well as information provided within this study, parents, pediatricians, and policy makers should continue to work to minimize adolescent exposure to alcohol marketing within and across this increasingly complex marketing landscape to mitigate this environmental risk for adolescent drinking.

Appendix A. Recall of alcohol marketing measure

| Intro | These questions ask about alcohol advertising that you may have seen or heard. Tell us how often you see or hear this TYPE of alcohol advertising. |

| a. | Internet advertising for alcohol brands (for example—alcohol commercials on the Internet before movies or videos, display or pop-up ads, brand websites, or social media pages) |

| b. | Alcohol brands shown in movies |

| c. | Alcohol brands shown in TV shows |

| d. | Alcohol commercials on TV |

| e. | Alcohol brands mentioned in popular music |

| f. | Magazine or newspaper advertisements for alcohol brands |

| g. | Billboards, signs, or banner advertisements for alcohol brands |

| h. | Display advertisements for alcohol brands (for example—a display at a grocery store or convenience store) |

| Response options are very often, often, sometimes, rarely, and never. |

Footnotes

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (K23AA021154 to Auden C. McClure, principal investigator; T32 DA037202 to Joy Gabrielli, and K02 AA13938 to Kristina M. Jackson); by a SYNERGY Scholars Award from the Dartmouth Center for Clinical and Translational Science (to Auden C. McClure, principal investigator); by the Dartmouth SYNERGY Clinical and Translational Science Institute, under award number UL1TR001086 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health; and by the Dartmouth Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research Center supported by Cooperative Agreement Number U48DP005018 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; the preparation, review, or approval of the article; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The findings and conclusions in this journal article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- Anderson P., de Bruijn A., Angus K., Gordon R., Hastings G. Impact of alcohol advertising and media exposure on adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2009;44:229–243. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn115. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agn115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin E. W. The message interpretation process model. In: Arnett J. J., editor. Encyclopedia of children, adolescents, and the media. Vol. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. pp. 535–536. [Google Scholar]

- Austin E. W., Chen M. J., Grube J. W. How does alcohol advertising influence underage drinking? The role of desirability, identification and skepticism. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:376–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.08.017. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychology. 2001;3:265–299. doi:10.1207/S1532785XMEP0303_03. [Google Scholar]

- Browne M. W., Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen K. A., Long J. S., editors. Testing structural equation models (Sage Focus ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Cin S., Worth K. A., Dalton M. A., Sargent J. D. Youth exposure to alcohol use and brand appearances in popular contemporary movies. Addiction. 2008;103:1925–1932. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02304.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Cin S., Worth K. A., Gerrard M., Gibbons F. X., Stoolmiller M., Wills T. A., Sargent J. D. Watching and drinking: Expectancies, prototypes, and friends’ alcohol use mediate the effect of exposure to alcohol use in movies on adolescent drinking. Health Psychology. 2009;28:473–483. doi: 10.1037/a0014777. doi:10.1037/a0014777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruijn A., Tanghe J., de Leeuw R., Engels R., Anderson P., Beccaria F., van Dalen W. European longitudinal study on the relationship between adolescents’ alcohol marketing exposure and alcohol use. Addiction. 2016;111:1774–1783. doi: 10.1111/add.13455. doi:10.1111/add.13455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Trade Commission. Self-regulation in the alcohol industry: Report of the Federal Trade Commission. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/self-regulation-alcohol-industry-report-federal-trade-commission/140320alcoholreport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon R., MacKintosh A. M., Moodie C. The impact of alcohol marketing on youth drinking behaviour: A two-stage cohort study. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2010;45:470–480. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agq047. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agq047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman E. W., Pinkleton B. E., Weintraub Austin E., Reyes-Velázquez W. Exploring college students’ use of general and alcohol-related social media and their associations with alcohol-related behaviors. Journal of American College Health. 2014;62:328–335. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2014.902837. doi:10.1080/07448481.2014.902837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson K. M., Janssen T., Gabrielli J. Media/marketing influences on adolescent and young adult substance abuse. Current Addiction Reports. 2018;5:146–157. doi: 10.1007/s40429-018-0199-6. doi:10.1007/s40429-018-0199-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen T., Cox M. J., Merrill J. E., Barnett N. P., Sargent J. D., Jackson K. M. Peer norms and susceptibility mediate the effect of movie alcohol exposure on alcohol initiation in adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2018;32:442–455. doi: 10.1037/adb0000338. doi:10.1037/adb0000338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D., Noel J., Landon J., Thornton N., Lobstein T. Alcohol marketing and youth alcohol consumption: A systematic review of longitudinal studies published since 2008. Addiction. 2017;112(Supplement 1):7–20. doi: 10.1111/add.13591. doi:10.1111/add.13591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D. H. Who is minding the virtual alcohol store? Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2012;166:866–867. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.608. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D. H., Padon A., Ross C., Borzekowski D. Self-reported youth and adult exposure to alcohol marketing in traditional and digital media: Results of a pilot survey. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2017;41:618–625. doi: 10.1111/acer.13331. doi:10.1111/acer.13331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D. H., Ross C. S., Ostroff J., McKnight-Eily L. R., Brewer R. D. & the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Youth exposure to alcohol advertising on television—25 markets, United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62:877–880. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D. H., Rushman A. E. Measuring youth exposure to alcohol marketing on social networking sites: Challenges and prospects. Journal of Public Health Policy. 2014;35:91–104. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2013.45. doi:10.1057/jphp.2013.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S. C., Magee C. A. Exposure to alcohol advertising and alcohol consumption among Australian adolescents. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2011;46:630–637. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agr080. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agr080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koordeman R., Anschutz D. J., Engels R. C. Alcohol portrayals in movies, music videos and soap operas and alcohol use of young people: Current status and future challenges. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2012;47:612–623. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/ags073. doi:10.1093/alcalc/ags073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyshon M. New media, new problem? Alcohol, young people and the Internet. 2011. Retrieved from http://www.ias.org.uk/uploads/pdf/News%20stories/ac-media-report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Lin E.-Y., Caswell S., You R. Q., Huckle T. Engagement with alcohol marketing and early brand allegiance in relation to early years of drinking. Addiction Research and Theory. 2012;20:329–338. doi:10.3109/16066359.2011.632699. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum R. C., Browne M. W., Sugawara H. M. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:130–149. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130. [Google Scholar]

- McClure A. C., Gabrielli J., Cukier S., Jackson K. M., Brennan Z. L., Tanski S. E. Internet alcohol marketing recall and drinking in underage adolescents. Academic Pediatrics. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2019.08.003. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2019.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure A. C., Stoolmiller M., Tanski S. E., Engels R. C., Sargent J. D. Alcohol marketing receptivity, marketing specific cognitions, and underage binge drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37(Supplement 1):E404–E413. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01932.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01932.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure A. C., Tanski S. E., Li Z., Jackson K., Morgenstern M., Li Z., Sargent J. D. Internet alcohol marketing and underage alcohol use. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20152149. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2149. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery K. C., Chester J., Grier S. A., Dorfman L. The new threat of digital marketing. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2012;59:659–675. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2012.03.022. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2012.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern M., Isensee B., Sargent J. D., Hanewinkel R. Attitudes as mediators of the longitudinal association between alcohol advertising and youth drinking. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2011;165:610–616. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.12. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern M., Sargent J. D., Sweeting H., Faggiano F., Mathis F., Hanewinkel R.2014Favourite alcohol advertisements and binge drinking among adolescents: A cross-cultural cohort study Addiction 1092005–2015doi:10.1111/add.12667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B., Muthén L. Mplus Version 7.11–Base Program and Combination Add-On. Los Angeles, CA: Authors; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Primack B. A., McClure A. C., Li Z., Sargent J. D. Receptivity to and recall of alcohol brand appearances in U.S. popular music and alcohol-related behaviors. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38:1737–1744. doi: 10.1111/acer.12408. doi:10.1111/acer.12408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S. P., Siegel M. B., DeJong W., Ross C. S., Naimi T., Albers A., Jernigan D. H. Brands matter: Major findings from the Alcohol Brand Research Among Underage Drinkers (ABRAND) project. Addiction Research & Theory. 2016;24:32–39. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2015.1051039. doi:10.3109/16066359.2015.1051039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C. S., Maple E., Siegel M., DeJong W., Naimi T. S., Ostroff J., Jernigan D. H. The relationship between brand-specific alcohol advertising on television and brand-specific consumption among underage youth. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014a;38:2234–2242. doi: 10.1111/acer.12488. doi:10.1111/acer.12488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C. S., Maple E., Siegel M., DeJong W., Naimi T. S., Padon A. A., Jernigan D. H. The relationship between population-level exposure to alcohol advertising on television and brand-specific consumption among underage youth in the US. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2015;50:358–364. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agv016. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agv016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C. S., Ostroff J., Siegel M. B., DeJong W., Naimi T. S., Jernigan D. H. Youth alcohol brand consumption and exposure to brand advertising in magazines. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014b;75:615–622. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.615. doi:10.15288/jsad.2014.75.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell C. A., Russell D. W., Boland W. A., Grube J. W. Television’s cultivation of American adolescents’ beliefs about alcohol and the moderating role of trait reactance. Journal of Children and Media. 2014;8:5–22. doi: 10.1080/17482798.2014.863475. doi:10.1080/17482798.2014.863475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent J. D., Wills T. A., Stoolmiller M., Gibson J., Gibbons F. X. Alcohol use in motion pictures and its relation with early-onset teen drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:54–65. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.54. doi:10.15288/jsa.2006.67.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel M., Ross C. S., Albers A. B., DeJong W., King C., III, Naimi T. S., Jernigan D. H. The relationship between exposure to brand-specific alcohol advertising and brand-specific consumption among underage drinkers—United States, 2011-2012. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2016;42:4–14. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2015.1085542. doi:10.3109/00952990.2015.1085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy A. W., Zogg J. B., Unger J. B., Dent C. W. Exposure to televised alcohol ads and subsequent adolescent alcohol use. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2004;28:498–509. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.28.6.3. doi:10.5993/AJHB.28.6.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]