Abstract

Objective:

Although research has documented harms associated with drinking within intimate relationships, there is evidence that some drinking patterns—characterized by congruent or shared partner drinking—may be associated with positive relationship functioning. The present dyadic daily diary study allowed us to consider whether congruent drinking events and drinking with partner increase the likelihood of experiencing intimacy with one’s partner within the next few hours.

Method:

Within a sample of 119 community couples in which both partners drank regularly, we studied the temporal relationship between drinking events and intimacy experiences using 56 days of daily reports. To ensure that the pattern of results was robust, we tested the effects of congruent versus noncongruent drinking events using different characterizations.

Results:

Drinking episodes involving simultaneous drinking by both partners (but not solo drinking) increased the likelihood of intimacy in the next few hours. Similarly, drinking episodes in which partner was present (but not episodes when partner was absent) and drinking episodes that took place at home (but not away from home) increased the likelihood of intimacy.

Conclusions:

Results provide the first evidence that some types of drinking events contribute to the occurrence of couple intimacy experiences within the next few hours and help to explain previously observed long-term effects of congruent drinking patterns on couple functioning.

Alcohol use within intimate relationships has been associated with poorer relationship functioning (Marshal, 2003), including intimate partner aggression (Cafferky et al., 2018; Foran & O’Leary, 2008) and divorce (Breslau et al., 2011; Waldron et al., 2011). However, drinking may also be a source of pleasure within intimate relationships, depending on the circumstances and patterning of partner alcohol use (Rodriguez & Derrick, 2017). Couples who drink together may experience more positive relationship outcomes over time (e.g., Homish & Leonard, 2005). However, few studies have considered the immediate, potentially positive consequences of drinking on couple interaction. The present dyadic, daily report study was designed to consider whether drinking episodes, reported independently by male and female intimate partners, increase the likelihood of partner intimacy experiences in the next few hours. We explored whether characteristics of these drinking episodes—congruency in partner drinking, presence of partner, and context of use—were influential predictors of subsequent self-reports of emotional and physical intimacy.

Immediate consequences of drinking episodes on social interaction

Alcohol is usually consumed in social settings and is believed to facilitate and enhance social interactions (Brown et al., 1980), including sexual intimacy (George & Stoner, 2000). Yet, there are relatively few studies examining its positive as opposed to its negative effects. A few studies provide evidence that alcohol use facilitates social interaction. For example, in a series of daily diary studies, naturally occurring social interactions that followed alcohol consumption (up to 3 hours prior) were characterized by greater positive and less negative affect compared with interactions without alcohol (Aan Het Rot et al., 2008). A few experimental studies have considered whether alcohol administered to dyads or groups influences social interactions. These studies suggest that drinking with others increases self-disclosure and verbal and nonverbal expressiveness. Among groups of unacquainted people, groups who drank alcohol (relative to placebo or no alcohol) displayed higher positive and lower negative affect and reported greater social bonding in unscripted conversations (Sayette et al., 2012). Similarly, groups who drank alcohol exhibited greater verbal activity and self-disclosure in a subsequent discussion than groups who did not (Lindfors & Lindman, 1987). We have been able to locate only one study that considered the effects of administered alcohol on the social interactions of community couples. Consistent with the notion that alcohol facilitates intimacy, Smith et al. (1975) found that consuming alcohol, relative to placebo, increased emotional expressivity in unstructured discussions between intimate partners. In a review of this literature, Fairbairn and Sayette (2014) conclude that within naturalistic social contexts among naive participants, alcohol reduces fear of social rejection, enhancing mood and facilitating emotional expression and self-disclosure.

Alcohol consequences within intimate partner dyads

Within close relationships, alcohol use may function as a source of conflict and tension or as a positive mechanism of bonding and shared activity (Rodriguez & Derrick, 2017). An emerging body of primarily survey research suggests that concordance or congruence in couple drinking is a key determinant of whether alcohol use promotes or impairs couple functioning (see Fischer & Wiersma, 2012, for a review). For example, couples with discrepant drinking patterns, relative to those who drank similar amounts, had greater declines in marital satisfaction (Foulstone et al., 2016; Homish & Leonard, 2007) and were more likely to divorce (Leonard et al., 2014; Torvik et al., 2013). The relative benefits of congruent versus discrepant drinking patterns may reflect the fact that couples who drink together spend more time in shared leisure activities, which contributes to relationship satisfaction and maintenance over time (Girme et al., 2014; see Kuykendall et al., 2015, for a review). Consistent with this view, couples who usually drank together reported higher marital satisfaction than couples who drank apart and comparable satisfaction to couples comprising nondrinkers (Homish & Leonard, 2005).

The positive long-term consequences of congruent couple drinking may also stem from short-term effects of drinking together on experiences of emotional and physical intimacy (Fairbairn & Sayette, 2014). Alcohol is commonly perceived as a means of enhancing intimacy within couples, particularly sexual intimacy (George & Stoner, 2000). Male and female partners with stronger alcohol-intimacy expectancies subsequently reported more episodes of drinking with partner (Levitt & Leonard, 2013). Derrick et al. (2010) found that women (although not men) in congruent heavy drinking couples had stronger alcohol intimacy expectancies than those in couples with discordant heavy drinking patterns. Previous positive drinking experiences within couples reinforce the belief or expectancy that drinking together facilitates intimacy, leading to continuation of the behavior (Levitt & Leonard, 2013; Levitt et al., 2014).

Two daily report studies provide evidence that drinking with one’s intimate partner, as opposed to drinking apart, may facilitate intimacy. Among college students, morning reports of perceived intimacy with partner (how close, happy, in love with) were higher and negative perceptions of partner behavior were lower the day after drinking with partner compared with reports that followed days of no drinking or drinking without partner (Levitt & Cooper, 2010). Of note, the effects of drinking quantity on relationship functioning depended on the quantity consumed by the partner, such that consuming similar amounts as one’s partner yielded better outcomes than consuming discrepant amounts. Using the present sample of adult couples, Levitt et al. (2014) again found that men and women reported higher positive relationship functioning (how loving, how well they got along with) and lower negative functioning (how angry, how much they argued) when they had reported drinking with partner the previous day compared with days following no drinking or drinking without partner. These studies provide evidence that certain drinking events—but not others—increase next-day couple functioning. Findings point toward the importance of partner drinking congruence, rather than the pharmacological effects of alcohol, for couple functioning.

Present study

The present study was designed to consider the immediate consequences of drinking events on male and female reports of the occurrence of partner intimacy within the next few hours. Following research suggesting that congruent social drinking facilitates social bonding and self-disclosure (Fairbairn & Sayette, 2014) and that congruent drinking patterns promote relationship functioning among intimate couples (Homish & Leonard 2005), we hypothesized that drinking episodes reflecting congruent partner drinking increase the likelihood of experiencing emotional and/or physical intimacy with one’s partner. We first tested the hypothesis that simultaneous drinking by male and female partners—that is, drinking by both at the same hour—would increase the likelihood of reporting intimacy in the next 3 hours relative to no drinking. We offered no hypothesis regarding the effects of drinking by only one partner. We also tested the effects of congruent drinking by considering the impact of drinking with partner events separately from drinking without partner events. Based on prior studies (Levitt & Cooper, 2010; Levitt et al., 2014), we hypothesized that drinking with partner would increase the likelihood of intimacy relative to no drinking but offered no hypothesis for drinking without partner relative to no drinking. As an exploratory aim, we compared the impact of drinking events that took place at home versus drinking episodes away from home. Although location is not a direct reflection of partner congruency, early studies suggest that drinking at home may be positively associated with marital intimacy and functioning compared with drinking away from home (Dunn et al., 1987; Roberts & Leonard, 1998).

Hypotheses were tested using partners’ independent reports of daily drinking and intimacy episodes provided over 56 consecutive days by heterosexual community couples. Primary analyses of these data have examined whether drinking episodes predict subsequent episodes of partner conflict and aggression (Testa & Derrick, 2014) and whether conflict and aggression episodes predict subsequent drinking episodes (Derrick & Testa, 2017). Data from this sample were also used to consider the impact of drinking events, with and without partner, on next-day relationship functioning (Levitt et al., 2014). However, the short-term temporal relationship between drinking episodes and intimacy episodes has not previously been examined using these or any other data. Use of the Actor Partner Interdependence Model (Kashy & Snyder, 1995; Kenny et al., 2006) allowed us to consider the independent effects of drinking by self (actor) and drinking by partner (partner) on intimacy experiences reported by male and female partners.

Method

Sample and recruitment

Participants were 119 married or cohabiting heterosexual couples, ages 21–46 (M = 33.35, SD = 6.82) recruited from the Buffalo area. Most responded to screening questionnaires sent to approximately 20,000 households (n = 77), with the remainder responding to Facebook (n = 27) or newspaper ads (n = 15). To be eligible, both partners had to drink four or more drinks per occasion at least monthly, report no contraindications to alcohol administration (e.g., pregnancy, medication, psychiatric or substance abuse treatment), and be willing to participate in an experimental alcohol administration study (Testa et al., 2014). These eligibility criteria yielded a sample of couples in which male and female partners drank similar amounts. Six months after the experimental study, couples were contacted and rescreened for eligibility and interest in participation in the 56-day daily report study. The sample was primarily White (93.1%), married (78.4%), employed (91.3% of men and 76.8% of women), and well educated (Mdneducation = 16 years).

Procedures

After providing written informed consent, couples were trained to make daily reports using the interactive voice response system. For 56 consecutive days, male and female partners were asked to make an independent report regarding the previous day’s activities and current functioning. They were compensated $1 for each report with bonuses of $10 for each complete week and $30 for 8 complete weeks. If one report was missed, an abbreviated make-up report could be made at the end of the next day’s report. If 2 or more days were missed, research staff called to obtain missing reports by telephone. As a consequence, there were very few missing reports. Men completed 6,591/6,608 reports (99.7%), with 5,810/6,608 (87.9%) on time; women completed 6,602/6,808 (99.9%) of reports, with 5,763/6,608 (87.2%) on time. All procedures were approved by the University at Buffalo Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Drinking events.

In each daily report, participants were asked: “Yesterday, did you drink any alcoholic beverages?” (0 = no, 1 = yes). If yes, they were asked the time drinking began using whole hours (e.g., 6 P.M., 7 P.M.), allowing us to determine the temporal ordering of drinking and intimacy events. Other follow-up questions included episode duration, number of drinks consumed, where drinking took place (home, bar, public place), and whether various other people were present (partner, friend, relative, no one). After reporting the event, participants were asked whether there was another drinking event that day and if so, provided similar data regarding that episode. All episodes were used in analyses.

Intimacy events.

Each daily report included the question: “At any time yesterday, did you have an interaction or meaningful conversation with your partner that involved intimacy, love, caring, or support?” (0 = no, 1 = yes) and if yes, the hour it occurred. Primary analyses considered the occurrence of intimacy as the outcome. If intimacy was reported, dichotomous follow-up questions, corresponding broadly to previously identified facets of couple intimacy (Marston et al., 1998) assessed whether the experience included the following: I provided comfort or emotional support; my partner provided comfort or emotional support; we had a meaningful, intimate or deep conversation; we cuddled or kissed; we had sex. In supplementary analyses, we considered as separate outcomes events involving emotional intimacy (positive response to give support, receive support, meaningful conversation) and events involving physical intimacy (cuddled/kissed or had sex). As with drinking events, participants could report a second intimacy event on the same day; all were used in analyses.

Analytic strategy

Outcome variables were male and female reports of intimacy, analyzed as dichotomous variables. We created hourly versions of the variables by dividing each day into 24 1-hour segments. Thus, for each couple, there were initially 1,344 rows of data, resulting in a total of 159,936 rows of data for analysis (24 hours × 56 days × 119 couples); however, most were made up of zeros given that relatively few hours included drinking or intimacy events (Testa & Derrick, 2014). To examine the temporal relationship between drinking events and intimacy events, we created lags for the predictor variables for the previous 3 hours and collapsed across these lagged variables to create a “moving window” that included episodes of drinking that began within the previous 3 hours up to and including the same hour. For example, a drinking episode was considered temporally precedent to an intimacy event occurring at 10 P.M. if it began at 7, 8, 9, or 10 P.M. The 3-hour window was chosen to approximate the period of elevated blood alcohol concentrations following drinking initiation and to be consistent with prior studies (e.g., Aan Hen Rot et al., 2008; Testa & Derrick, 2014). However, we considered other windows (2 hours, 4 hours), as well.

Given the interdependent nature of partners’ reports within a couple, we modeled equations for men and women simultaneously using multivariate multilevel modeling and Bayesian estimation within MPlus Version 8.2 (Gelman et al., 2014; Muthén & Muthén, 2017). The Bayes estimator uses the probit link function, which allowed us to specify a residual covariance between male and female dichotomous outcomes. We used the Actor Partner Interdependence Model to model the effects at both levels of each person’s own drinking (actor paths) and the effects of the partner’s drinking (partner paths) on each person’s intimacy reports.

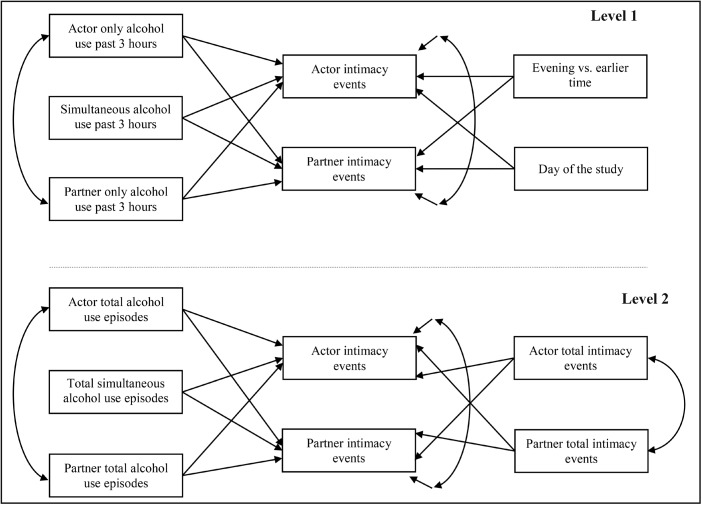

At Level 1 (the event level), we included the uncentered binary alcohol use variables (coded different ways for different analyses; see below). We also included time of day (uncentered; 1 = 5 p.M.–midnight, 0 = all other hours) and day of the study (1–56), grand mean centered, to account for the tendency for daily reports to decline over time (e.g., Testa & Derrick, 2014). At Level 2 (the couple level), we controlled for each partner’s total drinking episodes over 56 days (coded different ways for different analyses; see below), permitting distinguishing of within-person effects of drinking events from between-person effects. To be conservative, we also included total episodes of intimacy, since couples who experience more intimacy events overall are more likely to experience an intimacy event at a given hour (Testa et al., 2019). All Level 2 variables were grand mean centered (Enders & Tofighi, 2007). Level 1 and Level 2 effects are depicted in Figure 1. Additional details about our analytic approach are provided in the supplemental material, which appears as an online-only addendum to the article on the journal’s website.

Figure 1.

Level 1 and Level 2 predictors of actor and partner intimacy events

Results

Event reports

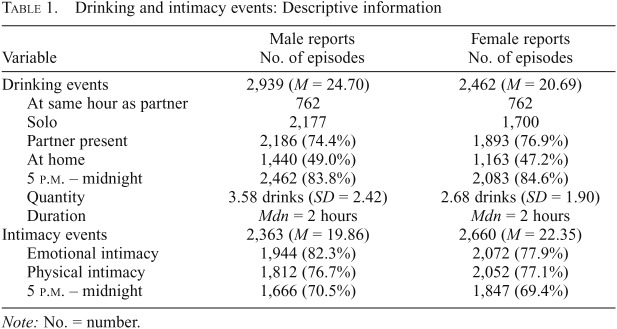

A total of 5,401 drinking episodes were reported on 5,048 days (of a possible 13,328 reporting days − 56 days × 119 couples). Men reported more drinking episodes (2,939 events on 2,731 days; M = 24.70 episodes, SD = 15.82) than women (2,462 events on 2,317 days; M = 20.69 episodes, SD = 14.38), t(5,399) = 15.301, p < .001. Because men and women reported drinking episodes independently, overlap in reports was modest. There were 762 episodes of simultaneous drinking in which both partners independently reported initiating drinking at the same hour. More commonly, drinking was reported at a given hour by only the male (2,177 episodes) or only the female (1,700 episodes), without a corresponding report by the partner. Male and female drinking episodes, presented in Table 1, were similar except that men consumed more drinks per episode (M = 3.58, SD = 2.42) than women (M = 2.68, SD = 1.90), t(5,398) = 14.944, p < .001.

Table 1.

Drinking and intimacy events: Descriptive information

| Variable | Male reports No. of episodes | Female reports No. of episodes |

| Drinking events | 2,939 (M = 24.70) | 2,462 (M = 20.69) |

| At same hour as partner | 762 | 762 |

| Solo | 2,177 | 1,700 |

| Partner present | 2,186 (74.4%) | 1,893 (76.9%) |

| At home | 1,440 (49.0%) | 1,163 (47.2%) |

| 5 P.m. – midnight | 2,462 (83.8%) | 2,083 (84.6%) |

| Quantity | 3.58 drinks (SD = 2.42) | 2.68 drinks (SD = 1.90) |

| Duration | Mdn = 2 hours | Mdn = 2 hours |

| Intimacy events | 2,363 (M = 19.86) | 2,660 (M = 22.35) |

| Emotional intimacy | 1,944 (82.3%) | 2,072 (77.9%) |

| Physical intimacy | 1,812 (76.7%) | 2,052 (77.1%) |

| 5 P.m. – midnight | 1,666 (70.5%) | 1,847 (69.4%) |

Note: No. = number.

A total of 5,023 intimacy events were reported on 4,498 days (Table 1). Women reported significantly more intimacy events (2,660 events on 2,372 days; M = 22.35 events, SD = 18.28) than men (2,363 events on 2,126 days; M = 19.86 events, SD = 17.31), t(5,021) = -3.693, p < .001. On 1,548 (23.2%) days both partners reported an intimate event, on 1,402 (21.0%) days one partner but not the other reported intimacy, and on 3,714 (55.7%) days neither reported intimacy. Most intimacy events included at least one type of emotional intimacy (4,016/5,023, 80.0%) and at least one type of physical intimacy (3,864/5,023, 76.9%), suggesting overlap rather than different types of events.

Temporal effects of drinking events on intimacy events

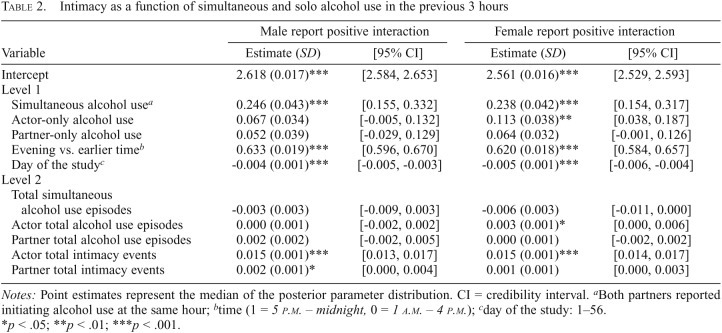

To test the hypothesis that simultaneous partner drinking (but not solo drinking) would have a positive effect on intimacy, we entered simultaneous drinking episodes (both partners reported drinking beginning at the same hour) and solo drinking episodes (drinking reported by only one partner beginning at a given hour) as independent predictors of intimacy. Number of drinks consumed was equivalent for solo (M = 3.17, SD = 1.26) and simultaneous events (M = 3.16, SD = 1.26), t(5,399) = -0.158, p = .874. Results of this analysis (the unstandardized Bayes median point estimates, posterior standard deviation, two-tailed p values [Gelman et al., 2014], and Bayesian 95% credibility intervals) are reported in Table 2 (models with standardized estimates are provided in the supplemental material). As hypothesized, simultaneous drinking increased the likelihood that male and female partners would report intimacy in the next 3 hours. With one exception, solo drinking episodes did not increase the likelihood of intimacy relative to no drinking. Intimacy events were more likely to be reported after 5 P.m., earlier in the daily report period, and by actors who reported more intimacy events; however, number of simultaneous drinking events did not influence reports of intimacy. The pattern of results was virtually identical when emotional and physical intimacy events were considered separately and when using a 2-hour or 4-hour window.

Table 2.

Intimacy as a function of simultaneous and solo alcohol use in the previous 3 hours

| Variable | Male report positive interaction |

Female report positive interaction |

||

| Estimate (SD) | [95% CI] | Estimate (SD) | [95% CI] | |

| Intercept | 2.618 (0.017)*** | [2.584, 2.653] | 2.561 (0.016)*** | [2.529, 2.593] |

| Level 1 | ||||

| Simultaneous alcohol usea | 0.246 (0.043)*** | [0.155, 0.332] | 0.238 (0.042)*** | [0.154, 0.317] |

| Actor-only alcohol use | 0.067 (0.034) | [-0.005, 0.132] | 0.113 (0.038)** | [0.038, 0.187] |

| Partner-only alcohol use | 0.052 (0.039) | [-0.029, 0.129] | 0.064 (0.032) | [-0.001, 0.126] |

| Evening vs. earlier timeb | 0.633 (0.019)*** | [0.596, 0.670] | 0.620 (0.018)*** | [0.584, 0.657] |

| Day of the studyc | -0.004 (0.001)*** | [-0.005, -0.003] | -0.005 (0.001)*** | [-0.006, -0.004] |

| Level 2 | ||||

| Total simultaneous alcohol use episodes | -0.003 (0.003) | [-0.009, 0.003] | -0.006 (0.003) | [-0.011, 0.000] |

| Actor total alcohol use episodes | 0.000 (0.001) | [-0.002, 0.002] | 0.003 (0.001)* | [0.000, 0.006] |

| Partner total alcohol use episodes | 0.002 (0.002) | [-0.002, 0.005] | 0.000 (0.001) | [-0.002, 0.002] |

| Actor total intimacy events | 0.015 (0.001)*** | [0.013, 0.017] | 0.015 (0.001)*** | [0.014, 0.017] |

| Partner total intimacy events | 0.002 (0.001)* | [0.000, 0.004] | 0.001 (0.001) | [0.000, 0.003] |

Notes: Point estimates represent the median of the posterior parameter distribution. CI = credibility interval.

Both partners reported initiating alcohol use at the same hour;

time (1 = 5 P.M. – midnight, 0 = 1 A.M. – 4 P.M.);

day of the study: 1–56.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

The above analysis included drinking and intimacy events that occurred at the same hour (e.g., both partners drank at 9 P.m. and one or both reported intimacy at 9 P.m.). Of simultaneous drinking hours, nearly half included a report of intimacy by one or both partners at the same hour (342/762, 44.9%). However, in these cases temporal ordering of drinking and intimacy is not clear. To ensure that drinking episodes preceded intimacy, we omitted hours in which drinking and intimacy both occurred by coding them as missing. In this more conservative analysis, drinking was considered to predict intimacy at 9 P.m. if it began during the 3 hours before the intimacy event (6, 7, or 8 P.m.) but not if it began at the same hour (9 P.m.). Omitting concurrent drinking – intimacy hours weakened the pattern of results shown in Table 2; the positive effect of simultaneous drinking remained for male but not for female intimacy events.

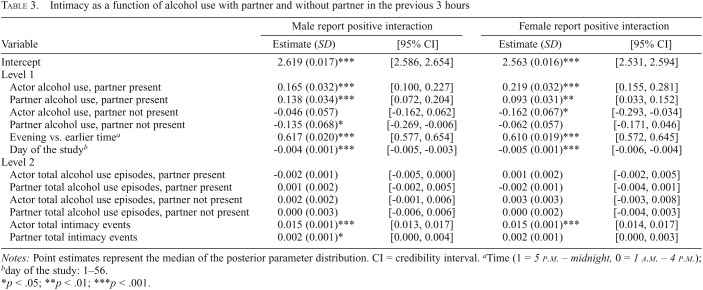

Drinking with partner and drinking at home

We tested two additional hypotheses using alternative classifications of drinking events. First, we tested the hypothesis that drinking with partner (but not drinking without partner) would positively predict intimacy, and second, that drinking at home (but not away from home) would predict intimacy. As expected, these two variables were associated. Drinking with partner events were more likely to occur at home (2,184/4,078, 53.5%) than drinking without partner events (418/1,320, 31.6%), χ2(1, n = 5,399) = 191.149, p < .001. Quantity of drinks consumed was significantly lower in home (M = 2.56, SD = 1.90) versus outside the home events (M = 3.73, SD = 2.38), t(5,397) = 19.898, p < .001) but did not differ for drinking with versus without partner events (p = .261).

Consistent with the first hypothesis, both actor and partner drink with partner events increased the likelihood of intimacy in the next 3 hours for men and women (Table 3). In addition, there was a negative effect of actor drinking without partner on female reports of intimacy and a negative effect of partner drinking without partner on male reports of intimacy. To ensure that findings were robust, we repeated analyses using 2- and 4-hour windows; the pattern remained the same. However, when we removed hours with concurrent drinking and intimacy events to ensure that drinking always preceded intimacy, the drink with partner pattern was weakened such that only partner (not actor) effects remained.

Table 3.

Intimacy as a function of alcohol use with partner and without partner in the previous 3 hours

| Variable | Male report positive interaction |

Female report positive interaction |

||

| Estimate (SD) | [95% CI] | Estimate (SD) | [95% CI] | |

| Intercept | 2.619 (0.017)*** | [2.586, 2.654] | 2.563 (0.016)*** | [2.531, 2.594] |

| Level 1 | ||||

| Actor alcohol use, partner present | 0.165 (0.032)*** | [0.100, 0.227] | 0.219 (0.032)*** | [0.155, 0.281] |

| Partner alcohol use, partner present | 0.138 (0.034)*** | [0.072, 0.204] | 0.093 (0.031)** | [0.033, 0.152] |

| Actor alcohol use, partner not present | -0.046 (0.057) | [-0.162, 0.062] | -0.162 (0.067)* | [-0.293, -0.034] |

| Partner alcohol use, partner not present | -0.135 (0.068)* | [-0.269, -0.006] | -0.062 (0.057) | [-0.171, 0.046] |

| Evening vs. earlier timea | 0.617 (0.020)*** | [0.577, 0.654] | 0.610 (0.019)*** | [0.572, 0.645] |

| Day of the studyb | -0.004 (0.001)*** | [-0.005, -0.003] | -0.005 (0.001)*** | [-0.006, -0.004] |

| Level 2 | ||||

| Actor total alcohol use episodes, partner present | -0.002 (0.001) | [-0.005, 0.000] | 0.001 (0.002) | [-0.002, 0.005] |

| Partner total alcohol use episodes, partner present | 0.001 (0.002) | [-0.002, 0.005] | -0.002 (0.001) | [-0.004, 0.001] |

| Actor total alcohol use episodes, partner not present | 0.002 (0.002) | [-0.001, 0.006] | 0.003 (0.003) | [-0.003, 0.008] |

| Partner total alcohol use episodes, partner not present | 0.000 (0.003) | [-0.006, 0.006] | 0.000 (0.002) | [-0.004, 0.003] |

| Actor total intimacy events | 0.015 (0.001)*** | [0.013, 0.017] | 0.015 (0.001)*** | [0.014, 0.017] |

| Partner total intimacy events | 0.002 (0.001)* | [0.000, 0.004] | 0.002 (0.001) | [0.000, 0.003] |

Notes: Point estimates represent the median of the posterior parameter distribution. CI = credibility interval.

Time (1 = 5 P.M. – midnight, 0 = 1 A.M. – 4 P.M.);

day of the study: 1–56.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

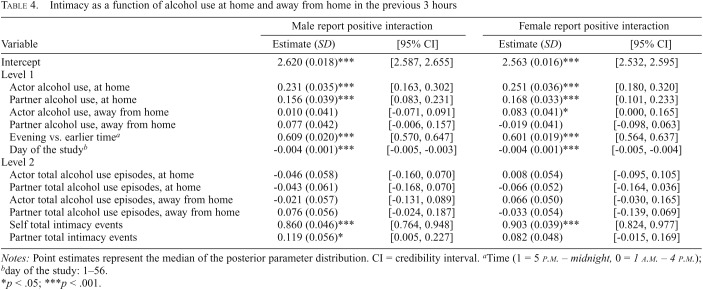

As shown in Table 4, there were positive actor and partner effects of drinking at home on intimacy reports by male and female partners. Drinking away from home was not associated with intimacy, with the exception of a modest positive effect on women’s reports of intimacy. Results were virtually identical when repeated using 2- and 4-hour windows and when we removed hours that included concurrent drinking and intimacy.

Table 4.

Intimacy as a function of alcohol use at home and away from home in the previous 3 hours

| Variable | Male report positive interaction |

Female report positive interaction |

||

| Estimate (SD) | [95% CI] | Estimate (SD) | [95% CI] | |

| Intercept | 2.620 (0.018)*** | [2.587, 2.655] | 2.563 (0.016)*** | [2.532, 2.595] |

| Level 1 | ||||

| Actor alcohol use, at home | 0.231 (0.035)*** | [0.163, 0.302] | 0.251 (0.036)*** | [0.180, 0.320] |

| Partner alcohol use, at home | 0.156 (0.039)*** | [0.083, 0.231] | 0.168 (0.033)*** | [0.101, 0.233] |

| Actor alcohol use, away from home | 0.010 (0.041) | [-0.071, 0.091] | 0.083 (0.041)* | [0.000, 0.165] |

| Partner alcohol use, away from home | 0.077 (0.042) | [-0.006, 0.157] | -0.019 (0.041) | [-0.098, 0.063] |

| Evening vs. earlier timea | 0.609 (0.020)*** | [0.570, 0.647] | 0.601 (0.019)*** | [0.564, 0.637] |

| Day of the studyb | -0.004 (0.001)*** | [-0.005, -0.003] | -0.004 (0.001)*** | [-0.005, -0.004] |

| Level 2 | ||||

| Actor total alcohol use episodes, at home | -0.046 (0.058) | [-0.160, 0.070] | 0.008 (0.054) | [-0.095, 0.105] |

| Partner total alcohol use episodes, at home | -0.043 (0.061) | [-0.168, 0.070] | -0.066 (0.052) | [-0.164, 0.036] |

| Actor total alcohol use episodes, away from home | -0.021 (0.057) | [-0.131, 0.089] | 0.066 (0.050) | [-0.030, 0.165] |

| Partner total alcohol use episodes, away from home | 0.076 (0.056) | [-0.024, 0.187] | -0.033 (0.054) | [-0.139, 0.069] |

| Self total intimacy events | 0.860 (0.046)*** | [0.764, 0.948] | 0.903 (0.039)*** | [0.824, 0.977] |

| Partner total intimacy events | 0.119 (0.056)* | [0.005, 0.227] | 0.082 (0.048) | [-0.015, 0.169] |

Notes: Point estimates represent the median of the posterior parameter distribution. CI = credibility interval.

Time (1 = 5 P.M. – midnight, 0 = 1 A.M. – 4 P.M.);

day of the study: 1–56.

p < .05;

p < .001.

Discussion

We hypothesized that drinking with one’s partner would increase the short-term likelihood of experiencing emotional and physical intimacy. Using different ways of classifying drinking events, we found consistent evidence that congruent partner drinking facilitates experiences of relationship intimacy. Simultaneous drinking, drinking with partner present, and drinking at home increased the likelihood of reporting intimacy experiences in the next 3 hours for men and women relative to no drinking. In contrast, drinking by only one partner, drinking without partner present, and drinking away from home had little or no effect on intimacy experiences. To our knowledge, this is the first study to consider the immediate effects of intimate partner drinking events on subsequent experiences of couple intimacy. The consistency of the pattern across different methods of characterizing drinking events bolsters confidence in the results.

The immediate positive consequences of drinking with partner events on perceived intimacy are consistent with, while extending considerably, previous analysis of these data, which demonstrated positive lagged effects of actor drinking with partner on next-day positive feelings toward partner (Levitt et al., 2014). Findings also help to explain the long-term positive effects of congruent drinking patterns on relationship satisfaction and stability (Homish & Leonard, 2005; 2007; Leonard et al, 2014). If we presume that these alcohol-facilitated intimacy experiences are rewarding and reflective of perceived partner responsiveness (Reis, 2013), the accumulation of such positive experiences is likely to contribute to relationship maintenance and satisfaction (Abelson, 1985; Murray et al., 2009). It would be valuable for future research to consider how these discrete events contribute to relationship functioning over time.

The increased likelihood of intimacy following drinking together is likely to be reinforcing, strengthening and sustaining beliefs about the positive consequences of drinking together for one’s relationship and leading to more such occasions (Derrick et al., 2010; Levitt & Leonard, 2013). Couples may even drink together as a way of improving relationship functioning (Levitt & Cooper, 2010). It is noteworthy that nearly half of all simultaneous drinking episodes also included an intimacy event at the same hour and drinking effects on intimacy were weakened when same hour events were removed. The close temporal association between drinking together and intimacy is consistent with popular expectancies and images of alcohol as a prelude to intimacy and may reflect a deliberate choice to drink to facilitate intimacy. The fact that only congruent drinking episodes and not all drinking episodes facilitated intimacy argues against a strictly pharmacological mechanism for the findings. However, the immediate positive effects of congruent drinking on intimacy are consistent with group drinking studies showing increased social bonding when all members of the group drank compared with groups that did not drink alcohol (incongruent drinking was not examined; Sayette et al., 2012).

Most literature establishing the relevance of partner drinking congruence has relied on survey data to demonstrate between-couple effects: couples characterized by congruent drinking report better relationship functioning (Homish & Leonard, 2005, 2007). An important innovation and extension of the present study is the ability to distinguish between-couple from within-couple drinking effects. We found consistent within-couple effects of congruent drinking occasions on intimacy but no between-couple effects; couples who reported more occasions of congruent drinking over the 56-day reporting period were not more likely to report intimacy at a given hour. The absence of between couples effects for congruent drinking may be specific to the sample since most, if not all, couples would be classified as congruent rather than discrepant drinkers. Nevertheless, the within-couples effects of congruent drinking occasions on intimacy is noteworthy given that most couples exhibited similar drinking patterns.

Limitations

Although daily reports provide a wealth of information on drinking and intimacy events that are unobtainable using survey methods, these data are not a perfect reflection of reality and pose challenges for data analysis decisions. As is common in couple daily data, partner reports of drinking and intimacy (and aggression; Derrick et al., 2014) overlapped only modestly. The modest correspondence may reflect actual differences in behavior (one partner drank, the other did not), differences in perception (one partner labels an experience as intimacy, the other does not), errors in recall precision (report event as occurring at 5 P.m. rather than 6 P.m.), or failure to report events that actually occurred. Assessment methodology permitted recording only of the event hour (e.g., 9 P.m.) rather than more specific times (e.g., began drinking at 9:00, intimacy at 9:25) or recording of which event preceded the other, posing challenges for temporal analyses. Because of these complexities, we analyzed data in several different ways. Results were stronger when we included the substantial number of drinking and intimacy events that occurred at the same hour rather than omitting these hours, suggesting a close or simultaneous temporal relationship between the two events. However, the consistency of results using different classifications of congruent drinking and different hourly windows provides confidence that findings are robust. Nonetheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that intimacy after drinking together reflects, at least in part, partner proximity; other shared activities may also increase perceived intimacy.

Results were obtained with a primarily White, well educated sample of frequent, moderate drinkers; very light drinkers and those with serious drinking problems were ineligible. Most, if not all, couples would be classified as congruent drinkers by virtue of similarity in partner drinking patterns and be expected to exhibit better couple functioning than couples with discrepant drinking (e.g., Homish & Leonard, 2007). The immediate, positive effects of congruent drinking occasions are consistent with maintenance of the relationship and drinking pattern within such a sample. It is not known whether congruent drinking events contribute to intimacy similarly among couples with dissimilar drinking patterns. On the other hand, despite congruency in partner drinking patterns, previous analyses within this sample revealed robust temporal effects of male and female drinking on the subsequent occurrence of verbal and physical aggression episodes (Testa & Derrick, 2014). Negative consequences following partner drinking events do not preclude positive effects on intimacy. Future research may endeavor to determine whether there are individual, dyadic, or situational factors that contribute to the likelihood of one or the other.

Footnotes

This research was supported by Grant R01 AA016127 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

References

- Aan Het Rot M., Russell J. J., Moskowitz D. S., Young S. N. Alcohol in a social context: findings from event-contingent recording studies of everyday social interactions. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:459–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00590.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abelson R. P. A variance explanation paradox: When a little is a lot. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;97:129–133. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.97.1.129. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J., Miller E., Jin R., Sampson N. A., Alonso J., Andrade L. H., Kessler R. C. A multinational study of mental disorders, marriage, and divorce. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2011;124:474–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01712.x. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01712.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. A., Goldman M. S., Inn A., Anderson L. R. Expectations of reinforcement from alcohol: Their domain and relation to drinking patterns. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1980;48:419–426. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.48.4.419. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.48.4.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cafferky B. M., Mendez M., Anderson J. R., Stith S. M. Substance use and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Psychology of Violence. 2018;8:110–131. doi:10.1037/vio0000074. [Google Scholar]

- Derrick J. L., Leonard K. E., Quigley B. M., Houston R. J., Testa M., Kubiak A. Relationship-specific alcohol expectancies in couples with concordant and discrepant drinking patterns. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:761–768. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.761. doi:10.15288/jsad.2010.71.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrick J. L., Testa M. Temporal effects of perpetrating or receiving intimate partner aggression on alcohol consumption: A daily diary study of community couples. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2017;78:213–221. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.213. doi:10.15288/jsad.2017.78.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrick J. L., Testa M., Leonard K. E. Daily reports of intimate partner verbal aggression by self and partner: Short-term consequences and implications for measurement. Psychology of Violence. 2014;4:416–431. doi: 10.1037/a0037481. doi:10.1037/a0037481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn N. J., Jacob T., Hummon N., Seilhamer R. A. Marital stability in alcoholic-spouse relationships as a function of drinking pattern and location. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1987;96:99–107. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.96.2.99. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.96.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders C. K., Tofighi D. Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:121–138. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbairn C. E., Sayette M. A. A social-attributional analysis of alcohol response. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140:1361–1382. doi: 10.1037/a0037563. doi:10.1037/a0037563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer J. L., Wiersma J. D. Romantic relationships and alcohol use. Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 2012;5:98–116. doi: 10.2174/1874473711205020098. doi:10.2174/1874473711205020098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran H. M., O’Leary K. D. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulstone A. R., Kelly A. B., Kifle T., Baxter J. Heavy alcohol use in the couple context: A nationally representative longitudinal study. Substance Use & Misuse. 2016;51:1441–1450. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2016.1178295. doi:10.1080/10826084.2016.1178295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A., Carlin J. B., Stern H. S., Rubin D. B. Bayesian Data Analysis (Vol. 2) Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- George W. H., Stoner S. A. Understanding acute alcohol effects on sexual behavior. Annual Review of Sex Research. 2000;11:92–124. doi:10.1080/10532528.2000.10559785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girme Y. U., Overall N. C., Faingataa S. ‘Date nights’ take two: The maintenance function of shared relationship activities. Personal Relationships. 2014;21:125–149. doi:10.1111/pere.12020. [Google Scholar]

- Homish G. G., Leonard K. E. Marital quality and congruent drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:488–496. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.488. doi:10.15288/jsa.2005.66.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homish G. G., Leonard K. E. The drinking partnership and marital satisfaction: The longitudinal influence of discrepant drinking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:43–51. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.43. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashy D. A., Snyder D. K. Measurement and data analytic issues in couples research. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:338–348. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.338. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny D. A., Kashy D. A., Cook W. L. Dyadic data analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kuykendall L., Tay L., Ng V. Leisure engagement and subjective well-being: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2015;141:364–403. doi: 10.1037/a0038508. doi:10.1037/a0038508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard K. E., Smith P. H., Homish G. G. Concordant and discordant alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use as predictors of marital dissolution. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:780–789. doi: 10.1037/a0034053. doi:10.1037/a0034053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt A., Cooper M. L. Daily alcohol use and romantic relationship functioning: Evidence of bidirectional, gender-, and context-specific effects. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36:1706–1722. doi: 10.1177/0146167210388420. doi:10.1177/0146167210388420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt A., Derrick J. L., Testa M. Relationship-specific alcohol expectancies and gender moderate the effects of relationship drinking contexts on daily relationship functioning. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:269–278. doi:10.15288/jsad.2014.75.269. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt A., Leonard K. E. Relationship-specific alcohol expectancies and relationship-drinking contexts: Reciprocal influence and gender-specific effects over the first 9 years of marriage. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:986–996. doi: 10.1037/a0030821. doi:10.1037/a0030821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindfors B., Lindman R. Alcohol and previous acquaintance: Mood and social interactions in small groups. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 1987;28:211–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.1987.tb00757.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9450.1987.tb00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal M. P. For better or for worse? The effects of alcohol use on marital functioning. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:959–997. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.002. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston P. J., Hecht M. L., Manke M. L., McDaniel S., Reeder H. The subjective experience of intimacy, passion, and commitment in heterosexual loving relationships. Personal Relationships. 1998;5:15–30. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.1998.tb00157.x. [Google Scholar]

- Murray S. L., Holmes J. G., Aloni M., Pinkus R. T., Derrick J. L., Leder S. Commitment insurance: Compensating for the autonomy costs of interdependence in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97:256–278. doi: 10.1037/a0014562. doi:10.1037/a0014562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L. K., Muthén B. O. Mplus users’ guide. 8th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Authors; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Reis H. T. Relationship well-being: The central role of perceived partner responsiveness. In: Hazan C., Campa M. I., editors. Human bonding: The science of affectional ties. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. pp. 283–307. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts L. J., Leonard K. E. An empirical typology of drinking partnerships and their relationship to marital functioning and drinking consequences. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1998;60:515–526. doi:10.2307/353866. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez L. M., Derrick J. Breakthroughs in understanding addiction and close relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2017;13:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.011. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette M. A., Creswell K. G., Dimoff J. D., Fairbairn C. E., Cohn J. F., Heckman B. W., Moreland R. L. Alcohol and group formation: A multimodal investigation of the effects of alcohol on emotion and social bonding. Psychological Science. 2012;23:869–878. doi: 10.1177/0956797611435134. doi:10.1177/0956797611435134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. C., Parker E. S., Noble E. P. Alcohol and affect in dyadic social interaction. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1975;37:25–40. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197501000-00004. doi:10.1097/00006842-197501000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M., Crane C. A., Quigley B. M., Levitt A., Leonard K. E. Effects of administered alcohol on intimate partner interactions in a conflict resolution paradigm. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:249–258. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.249. doi:10.15288/jsad.2014.75.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M., Derrick J. L. A daily process examination of the temporal association between alcohol use and verbal and physical aggression in community couples. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:127–138. doi: 10.1037/a0032988. doi:10.1037/a0032988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M., Wang W., Derrick J. L., Leonard K. E. Marijuana use episodes and partner intimacy experiences: A daily report study. Cannabis. 2019;2:19–28. doi: 10.26828/cannabis.2019.01.002. doi:10.26828/cannabis.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torvik F. A., Røysamb E., Gustavson K., Idstad M., Tambs K. Discordant and concordant alcohol use in spouses as predictors of marital dissolution in the general population: Results from the Hunt study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37:877–884. doi: 10.1111/acer.12029. doi:10.1111/acer.12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron M., Heath A. C., Lynskey M. T., Bucholz K. K., Madden P. A. F., Martin N. G. Alcoholic marriage: Later start, sooner end. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35:632–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01381.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01381.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]