Abstract

Talaromycosis is endemic in Southeast Asia and is commonly described in HIV-infected patients. We describe the first case of Talaromycosis in HIV-infected patient in Burkina Faso. This is an 83-year-old man with skin lesions on the right foot. The thick scales were used for the mycological examination. Microscopic examination of growth allowed isolation of Talaromyces marneffei in its yeast and mold forms. The patient was treated successfully with Itraconazole (400 mg/day) for 8 weeks.

Keywords: Talaromycosis, Talaromyces marneffei, dimorphic fungus, Burkina Faso

1. Introduction

Talaromyces marneffei (formerly Penicillium marneffei) is an opportunistic dimorphic fungus responsible for talaromycosis (formerly known as penicilliosis). It has been more described in Southeast Asia in HIV-infected patients [1,2]. It is an emerging deep mycosis responsible for systemic involvement and is more often located in the skin, lungs and reticuloendothelial system [3,4]. T. marneffei exists in two forms (yeast and mold) depending on the temperature of the medium. This dimorphism is characteristic of the T. marneffei species, making it possible to differentiate it with the other species of Talaromyces. The yeast form is observed at 37 °C (body temperature) in tissue and culture medium. The mold form (filamentous) is observed at 25 °C–30 °C. T. marneffei is an intracellular fungus and his survival in macrophages is responsible for its virulence [5,6].

Talaromycosis is poorly described in the world. It is geographically limited in Southeast Asia where it is endemic, particularly in Thailand. The prevalence of talaromycosis has increased significantly with the advent of the HIV pandemic [4,7]. The natural reservoir of the fungus and modes of transmission are still unclear although several studies implicate the role of bamboo rats (Asian rodents) in contamination [8]. In northern Thailand, it is the third most opportunistic infection after tuberculosis and cryptococcosis in HIV-infected patients [4]. The infection has been described in HIV-infected patients with CD4+ count less than 100/μL [9]. It is rare in Europe and all the cases described were residents or had a stay in an endemic area. In West Africa, a case had been reported in Germany from a patient from Ghana who had never been to SouthEast Asia [7,10]. In Burkina Faso, no case of T. marneffei infection had been reported, although HIV infection is widespread [3,7].

The recommended treatment for talaromycosis combines Amphotericin B with Itraconazole [9,11]. But these molecules are not always accessible in Burkina Faso. Mortality due to T. marneffei in HIV-infected patients would be 100% in absence of treatment [7,9].

Here we describe the first case reported of T. marneffei infection in an HIV-infected patient in Burkina Faso.

2. Case

The patient is a retired 83-year-old former public servant who has been suffering from liver-foot skin lesions that have lasted more than year −1. His history included HIV infection since years −9 and followed by the first-line ART regimen recommended in the country (TDF + FTC + EFV) and cotrimoxazole 960 mg. He was not taking his treatment properly and the follow-up was not regular. No travel history with a trip to Asia was noted. The patient had not traveled outside Burkina Faso during the last five years. The beginning of the symptoms was marked by small prurinous nodules and periodic fever. He then consulted several doctors and most of the treatments were oral unspecified antibiotics. He was seen in consultation at the National Hospital in Ouagadougou for persistent itching in the right foot.

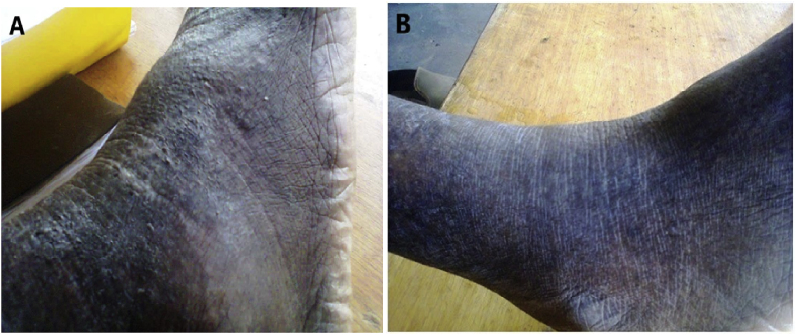

Physical examination showed that the patient was in good condition. Examination of the right foot revealed irregular hyperkeratotic verrucous warty skin lesions with nodules and hyperpigmented healed plaques. A slight extension was observed on the outer side of the ipsilateral leg with erythematous and crusty scarred areas covered with scales (Fig. 3A). There was no fever or other symptoms that could affect other parts of the body.

Fig. 3.

Observation of the evolution of lesions of the right foot. (A) Nodular hyperkeratotic lesions with scarred areas - (B) Disappearance of lesions after week +10 of treatment.

The results of the blood count revealed slight anemia (10.7 g/dL), leukopenia (1.9 × 103/mm3), lymphopenia (1.24 × 103/μL) neutropenia (0.86 × 103/μL). The C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated at 54 mg/L. The qualitative study of the anti-HIV antibodies performed by the Alere Determine™ Immunochromatographic Test was positive and the HIV-1 type was confirmed by immunoblot determining. The CD4+ T lymphocyte count was 240 cells/μL and the viral load was below the limit of detection (150 copies /mL) at RT-PCR. Serological tests for hepatitis B and C were negative. The biochemical parameters were normal. The blood culture was negative at days +10.

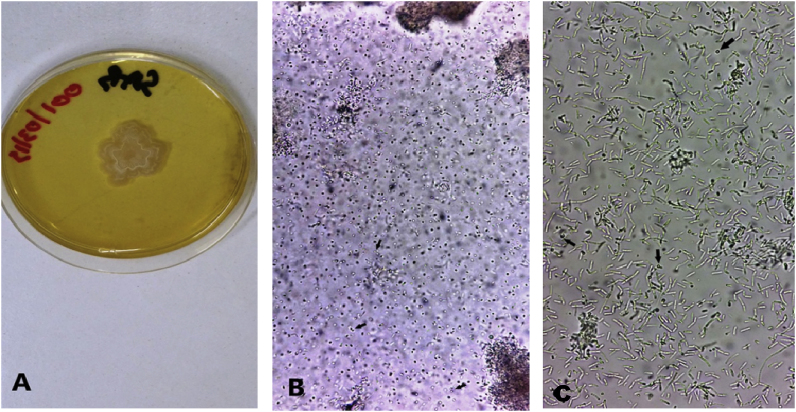

The mycological examination was performed from scale samples. The culture was carried out on a Sabouraud agar medium at 37 °C and 27 °C.

At 37 °C, beige and creamy colonies grew after day +1 (Fig. 1A). Microscopic examination of the colony showed the yeast form of T. marneffei with the presence of rounded and elliptical cells and a characteristic division by binary fission giving two anucleate cells (Fig. 1B). Arthroconidia and ascospores in germination were also seen (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Observation of the culture at 37 °C. (A) Creamy smooth and beige colonies. (B,C) Stages of sexual reproduction of T. marneffei- (B) Division by binary fission of yeast (arrows) - (C) Ascospores in germination (arrows) and arthroconidia.

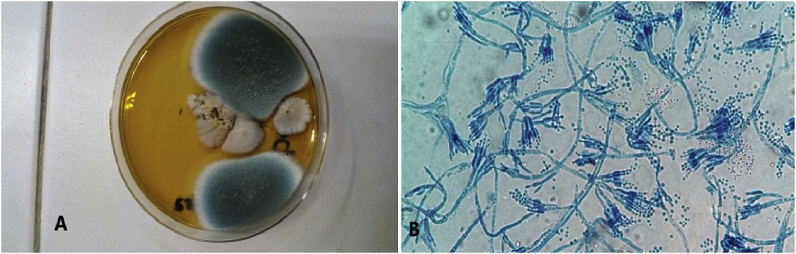

After days +3 of culture at 27 °C fluffy and gray colonies had grown (Fig. 2A). Microscopic observation revealed septal mycelial filaments with branched conidiophores bearing tight phialides against each other and producing conidia arranged in a chain (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Observation of the culture at 27°C- (A) Gray fluffy colonies - (B) Microscopic identification with presence of conidiophores with ramifications carrying phialides and chain-aligned conidia.

The treatment consisted of oral administration of 400 mg Itraconazole daily for 8 weeks followed by a maintenance dose of 200 mg daily for 6 weeks, with regular monitoring of the management of HIV infection. The skin lesions decreased during treatment. After weeks +10 of therapeutic follow-up, the patient was cured with disappearance of skin lesions (Fig. 3B). He continued his treatment at dose of 200 mg up to 6 weeks. There was an excellent response to the therapy.

3. Discussion

T. marneffei is a fungus responsible for opportunistic infection in immunocompromised patients. In deep and systemic lesions mortality is certain when diagnosis and treatment are delayed [9,12,13]. The mycological diagnosis is easy and requires an experienced manipulator. The infection is more known in Asia but remains more or less underestimated or neglected in Africa. Cases reported outside endemic areas are rare [9]. We describe the first case reported in an HIV-infected patient with a cutaneous localization of talaromycosis in Burkina Faso.

Infection by T. marneffei is geographically limited in the south-east. The only reported case in West Africa was in plantations and the source of the infection was unknown [6,9]. This case is an HIV-infected native from Burkina Faso who has never been to Asia and has not traveled outside the country in the last five years.

The transmission of T. marneffei remains unclear. The fungus is present in the soil and can be transmitted by any traumatic agent. The cutaneous localization of the infection at the level of the lower limb can be favored by micro wounds of gardening plants or other grasses parasitized by the fungus. Climatic conditions (25 °C–30 °C) are a factor favoring contamination by inhalation of spores (conidia) and responsible for pulmonary involvement [4,14,15].

The reported cases of T. marneffei infection had a CD4 count of less than 100 cells/μL. This case had a CD4 count of 240 cells/μL. This result shows that the risk of T. marneffei infection exists despite a CD4 count greater than 100 cells/μL [11]. Talaromycosis is an opportunistic disease that may be associated with other infections in immunocompromised patients. T. marneffei should be commonly sought as opportunistic infections [9,16]. The development of serological tests for the rapid identification of T. marneffei circulating antigen would be an input into the diagnosis and monitoring of treatment [13,17].

In Burkina Faso, T. marneffei infection is not known to clinicians. The current epidemiology of talaromycosis in the country is probably inaccurate due to insufficient technical platform for mycological diagnosis. Particular attention should be given to this infection in the population of HIV-infected patients. The recommended treatment is based on the use of Amphotecycin B with an oral relay with Itraconazole [11]. Treatment of the patient was administered orally at a single dose of 400 mg of Itraconazole for 8 weeks, followed by a maintenance dose of 200 mg for 6 weeks. Itraconazole alone is therefore effective in the treatment of cutaneous involvement of talaromycosis [18].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the team of laboratory of the pediatric hospital Charles De-Gaulle for their collaboration especially Yacine R. Ouattara and Germaine K. Ouedraogo for their involvement.

References

- 1.Xu X., Ran X., Pradhan S., Lei S., Ran Y. Dermoscopic manifestations of Talaromyces (Penicillium) marneffei infection in an AIDS patient. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2019;85(3):348. doi: 10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_118_17. http://www.ijdvl.com/text.asp?2019/85/3/348/233796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clyti E., Sayavong K., Monchy D., Chanthavisouk K. Pénicilliose au Laos. Presse Med. 2006;35(3):427–429. doi: 10.1016/s0755-4982(06)74610-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matos A.C., Alves D., Saraiva S., Soares A.S., Soriano T., Figueira L. Isolation of Talaromyces marneffei from the skin of an Egyptian Mongoose (Herpestes ichneumon) in Portugal. J. Wildl. Dis. 2019;55(1):238–241. doi: 10.7589/2017-02-037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanittanakom N., Cooper C.R., Fisher M.C., Sirisanthana T. Penicillium marneffei infection and recent advances in the epidemiology and molecular biology aspects. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006;19(1):95–110. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.1.95-110.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woo P.C.Y., Lam C.W., Tam E.W.T., Leung C.K.F., Wong S.S.Y., Lau S.K.P. First discovery of two polyketide synthase genes for mitorubrinic acid and mitorubrinol yellow pigment biosynthesis and implications in virulence of Penicillium marneffei. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2012;6(10):e1871. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woo P.C.Y., Lau S.K.P., Lau C.C.Y., Tung E.T.K., Chong K.T.K., Yang F. Mp1p is a virulence factor in Talaromyces (Penicillium) marneffei. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2016;10(8):e0004907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.000490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong S.Y., Wong K.F. Penicillium marneffei infection in AIDS. Pathol. Res. Int. 2011;2011:764293. doi: 10.4061/2011/764293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gugnani H., Fisher M.C., Paliwal-Johsi A., Vanittanakom N., Singh I., Yadav P.S. Role of Cannomys badius as a natural animal host of Penicillium marneffei in India. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42(11):5070–5075. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.11.5070-5075.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohsin J., Khalili S.A., Van den Ende A.H.G.G., Khamis F., Petersen E., De Hoog G.S. Imported talaromycosis in Oman in advanced HIV: a diagnostic challenge outside the endemic areas. Mycopathologia. 2017;182(7):739–745. doi: 10.1007/s11046-017-0124-x. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5500679/pdf/11046_2017_Article_124.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lo Y., Tintelnot K., Lippert U., Hoppe T. Disseminated Penicillium marneffei infection in an African AIDS patient. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2000;94(2) doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(00)90271-2. 187-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masur H., Brooks J.T., Benson C.A., Holmes K.K., Pau A.K., Kaplan J.E. Updated guidelines from the centers for disease control and prevention, National institutes of health, and HIV medicine association of the infectious diseases society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014;58:1308–1311. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong S.C.Y., Sridhar S., Ngan A.H.Y., Chen J.H.K., Poon R.W.S., Lau S.K.P. Fatal Talaromyces marneffei infection in a patient with autoimmune hepatitis. Mycopathologia. 2018;183(3):615–618. doi: 10.1007/s11046-017-0239-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hulshof C.M.J., Van Zanten R.A.A., Sluiters J.F., Van der Ende M.E., Samson R.S., Zondervan P.E., Wagenvoort J.H.T. Penicillium marneffei infection in an AIDS patient. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1990;9:370. doi: 10.1007/BF01973751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Y., Huang X., Yi X., He Y., Mylonakis E., Xi L. Detection of Talaromyces marneffei from fresh tissue of an inhalational murine pulmonary model using nested PCR. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0149634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baradkar V., Kumar S., Kulkami S.D. Penicillium marneffei : the pathogen a tour doorstep. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2009;75(6):619–620. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.57733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatakeyama S., Yamashita T., Sakai Y., Kamei K. Case report: disseminated Talaromyces (Penicillium) marneffei and Mycobacterium tuberculosis coinfection in a Japanese patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017;97(1):38–41. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ning C., Lai J., Wei W., Zhou B., Huang J., Jiang J. Accuracy of rapid diagnosis of Talaromyces marneffei: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0195569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thanh N.T., Vinhb L.D., Liemb N.T., Shikumad C., Daya J.N., Thwaitesa G. Clinical features of three patients with paradoxical immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome associated with Talaromyces marneffei infection. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2018;19:33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]