Abstract

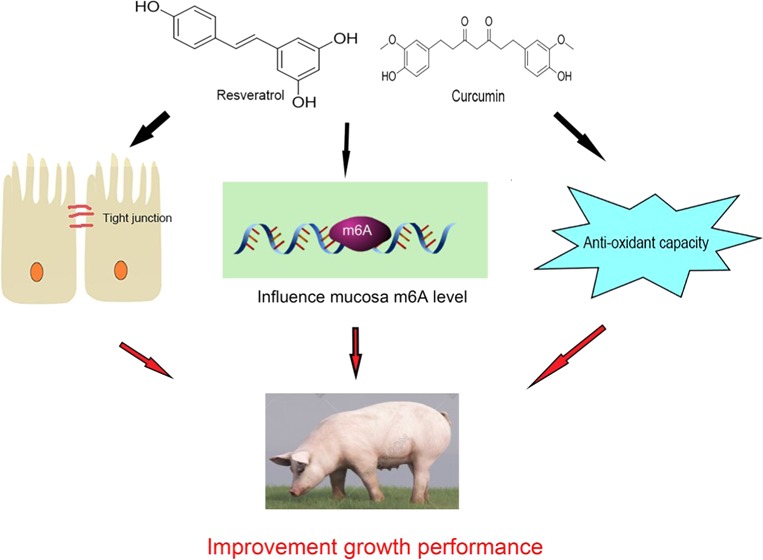

N6-Methyladenosine (m6A) is the most prevalent modification on eukaryotic messenger RNA (mRNA). Resveratrol and curcumin, which can exert many health-protective effects, may have a relationship with m6A RNA methylation. We hypothesized that the combination of resveratrol and curcumin could affect growth performance, intestinal mucosal integrity, m6A RNA methylation, and gene expression in weaning piglets. One hundred and eighty piglets weaned at 28 ± 2 days were fed a control diet or supplementary diets (300 mg/kg of antibiotics; 300 mg/kg of each resveratrol and curcumin; 100 mg/kg of each resveratrol and curcumin; 300 mg/kg of resveratrol; 300 mg/kg of curcumin) for 28 days. The results showed that the combination of resveratrol and curcumin improved growth performance and enhanced intestinal mucosal integrity and functions in weaning piglets. Resveratrol and curcumin also increased intestinal antioxidative capacity and mRNA expression of tight junction proteins. Furthermore, resveratrol and curcumin decreased the content of m6A and decreased the enrichment of m6A on the transcripts of tight junction proteins and on heme oxygenase-1 in the intestine. Our findings indicated that the combination of resveratrol and curcumin increased growth performance, enhanced intestine function, and protected piglet health, which may be associated with changes in m6A methylation and gene expression, suggesting that curcumin and resveratrol may be a potential natural alternative to antibiotics.

Introduction

The intestinal mucosal barrier, which is responsible for nutrient absorption and immunological stimuli, is very important for the neonate development and health,1 particularly in piglets. Due to oxidative stress, nutritional and environmental challenges, weaning leads to intestinal mucosal barrier impairment, immune function disruption, diarrhea, growth retardation, and even deaths in piglets.2 Traditionally, antibiotics have been used to relieve weaning stress in piglets; however, antibiotics were prohibited from use in animal feeds in the European Union this year because of concerns about residues in animal products and the potential appearance of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Some natural products can exert mucosa barrier protecting ability and may have the potential to improve weaning stress. Resveratrol is a phenylpropanoid compound present in strongly pigmented vegetables and fruits. Curcumin (diferuloylmethane) is derived from Curcuma longa (turmeric plant). Accumulating evidence indicates that these natural products have immunomodulatory, antioxidative, antiapoptotic, and antiinflammatory functions.3−5 In addition, resveratrol and curcumin can protect intestinal epithelial barrier against dysfunction under oxidative stress and immune challenge.3 However, their utility is limited because of low bioavailability.6−8 Furthermore, resveratrol and curcumin regulate many genes expression to exert their biological function9,10 but the underlying mechanisms remain unclear.

Among over 100 distinct RNA chemical modifications identified thus far, N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most abundant internal modification of eukaryotic messenger RNAs (mRNAs). Dynamic and reversible m6A methylation is catalyzed by RNA methyltransferase, including methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3), methyltransferase-like 14 (METTL14),11 Wilms tumor 1-associated protein, and demethylases, including fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) and alkylated DNA repair protein AlkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5).12 In addition, m6A binding proteins are predominantly in the YT521-B homology (YTH) family and contain the YTH domain (YTHDF1, YTHDF2, YTHDF3, YTHDC1, and YTHDC2).13 A growing amount of evidence indicates that m6A RNA methylation plays a critical role in the regulation of gene expression for fundamental cellular processes, including RNA processing, RNA splicing, RNA nucleation, RNA degradation, and RNA translation.14,15 In addition, m6A methylation is involved in diverse physiological functions, including obesity, immunoregulation, stem cell differentiation, and human chronic diseases.16−18 Interestingly, recent studies showed that a high-fat diet, betaine, and cycloleucine affect the m6A RNA methylation patterns,19,20 altering the gene expression, suggesting that nutritional challenge regulates the dynamic and reversible nature of m6A modification.

Our hypothesis is that resveratrol and curcumin affect growth performance, m6A methylation, and gene expression in the intestine of piglets after weaning, and these compounds may have synergistic effects. We investigated the effect of the combination of resveratrol and curcumin on growth performance, intestinal morphology, antioxidant activity, tight junction protein gene expression, the total content of m6A, and the levels of m6A on the transcript. Pigs are very similar to humans in anatomy, genetics, and physiology; consequently, pigs are an excellent animal model to study human diseases,21 and therefore, we choose weaned piglets as the animal model in this experiment.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Experimental Design

All of the procedures were carried out in accordance with the Chinese Guidelines for Animal Welfare and Experimental Protocol and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanjing Agricultural University, China (NJAU-CAST-2015-098). One hundred and eighty (90 ♂ + 90 ♀) piglets with an initial body weight of 7.8 ± 0.6 kg (weaned at 28 ± 2 days) were randomly divided into six groups that were fed a control diet supplemented with additives as follows: no addition (CON); 159 mg/kg of olaquindox + 81 mg/kg of kitasamycin + 60 mg/kg of chlortetracycline (ANT); 300 mg/kg resveratrol and curcumin (HRC); 100 mg/kg resveratrol and curcumin (LRC); 300 mg/kg of resveratrol (RES); 300 mg/kg of curcumin (CUR), respectively. All pigs were housed in pens in an environmentally controlled room (25.0 ± 0.5 °C) and were allowed to consume feed and water ad libitum. Each treatment had six replicates and five pigs per replicate. The compositions of the diets are presented in Table S1 and met the NRC (2012) requirements for nutrition. Curcumin (≥98%) was obtained from the Cohoo Biotech Research & Development Center (Guangzhou, China). Resveratrol (CAS number 501-36-0, ≥98%) was purchased from Seebio Bio-technology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). One replicate in each group consumed the diet in which the inert marker yttrium oxide (Y2O3) was added in a percentage of 0.01% to measure apparent digestibility.22,23 The average daily gain (ADG), average daily feed intake (ADFI), and feed conversion ratio (FCR) of piglets were recorded carefully. Feed leftovers were collected after each meal and recorded weekly for calculating average daily feed intake (ADFI). Body weight was recorded weekly for calculating average daily gain (ADG) and feed conversion ratio (FCR).

Sample Collection

At 42 days of postnatal age, blood samples were obtained by jugular venipuncture and heparin sodium was added for anticoagulation. At 56 days of postnatal age, one piglet from each replicate was selected (n = 6). After electrical stunning, blood samples were collected and centrifuged at 3500g for 15 min at 4 °C and then stored at −80 °C. After blood collection, piglets were sacrificed by the exsanguination. The entire small intestine starting from the pyloric sphincter to the ileocecal valve was removed from the abdominal cavity and divided into three segments, including the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. The jejunal and ileal segments were immediately washed with ice-cold physiological saline to remove the luminal contents. Approximately 1 cm intestine sections from the middle of jejunum and ileum were collected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. The middle of jejunal and ileal mucosae was scraped using a glass microscope slide24 and were then snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for further analysis.

Laboratory Analysis

Fecal samples were collected from each pen. They were dried at 100 °C for 48 h, milled through a 1 mm screen, and homogenized before analysis. The apparent digestibility of nutrients was calculated as described previously.25 The diet and fecal samples were analyzed for Y2O3 concentrations.22,23 Ash was determined after ignition of a known weight of diet or feces in a muffle furnace at 500 °C and the dry matter (DM) of the diets/feces was determined after drying overnight at 103 °C.23 The apparent digestibility was determined using the formula

|

Intestinal Morphology

The intestinal segments fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde were dried using a graded series of xylene and ethanol and embedded in paraffin. The samples (5 μm) were then deparaffinized using xylene and rehydrated with graded dilutions of ethanol. The slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Six slides for each tissue were prepared, and the images were acquired using an optical binocular microscope with a digital camera (Nikon ECLIPSE 80i, Tokyo, Japan).

Measurement of Intestinal Enzyme Activities, Plasma d-Lactate, and Diamine Oxidase (DAO)

The plasma DAO activity and the level of d-lactate were measured by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Shanghai Yili Biological Technology Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China). The activities of intestine glutathione peroxidase (GSH-PX), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and the concentrations of glutathione (GSH), oxidized glutathione (GSSG), malondialdehyde (MDA), total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC), sucrase, maltase, and lactase were determined using the commercial kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All results were normalized to the total protein concentration in each sample for intersample comparison. The protein concentrations were quantified using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China).

Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA from intestinal mucosa was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, Jiangsu, China). DNase was added to remove contaminant DNA. After the quantification and unified concentration, total RNA was reversed-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using a reverse transcription kit (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, Jiangsu, China). The primer sequences are listed in Table S2 and synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The cDNA was amplified using the ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, Jiangsu, China). The relative gene expression was calculated by the 2–ΔΔCT method after normalization to β-actin.

m6A Immunoprecipitation (IP) and Gene-Specific m6A qRT-PCR

The relative abundance of occludin (OCLN), claudin 1 (CLDN1), zonula occluden (ZO-1), and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) mRNA in m6A antibody IP samples and input samples was assessed by qRT-PCR. Total RNA was isolated from mucosa with TRIzol reagent (Vazyme) followed by polyadenylated RNA extraction using Dynabeads mRNA DIRECT (Invitrogen) kit. A 200 ng aliquot of mRNA was saved as input samples. The remaining mRNA was used for m6A-immunoprecipitation as given in Dominissini et al.14 and Zhong et al.26 A 5 μg aliquot of mRNA was incubated with m6A antibody (Abcam) in IP buffer (10 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Igepal CA-630) supplemented with RNase inhibitor (Fermentas) for 2 h at 4 °C. Dynabeads Protein A (Invitrogen) was added to the solution and rotated for an additional 2 h at 4 °C. After washing with IP buffer, mRNA was eluted from the beads via incubation in 300 mL elution buffer (0.1 M NaCI, 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.05% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 200 mg/mL proteinase K) for 1.5 h at 50 °C. Finally, m6A IP mRNA was recovered by ethanol precipitation, purified by phenol/chloroform extraction, and analyzed by qRT-PCR. Primer sequences are listed in Table S3.

Quantification of m6A by Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC–MS/MS)

Messenger RNA was subjected to liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) for the determination of m6A as previously described.13,26 Briefly, 100–200 ng of mRNA was digested by P1 nuclease (Fisher Scientific) in 25 μL of buffer containing 2.0 mM ZnCl2 and 10 mM NaCl for 2 h at 37 °C. Subsequently, 1 μL of alkaline phosphatase and 2.5 μL of NH4HCO3 were added and the sample was incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. The sample was then diluted with 75 μL of RNase-free water and filtered through a 0.22 mm poly(vinylidene fluoride) filter (Millipore). Finally, the sample was injected into a C18 reverse-phase column coupled on-line to Agilent 6410 triple-quadrupole LC mass spectrometer in multiple reactions monitoring positive electrospray ionization mode. The nucleosides were quantified using the nucleoside to base ion mass transitions of 282.1–150.1 (m6A) and 268.0–136.0 (A). Concentrations of nucleosides in mRNA samples were deduced by fitting the signal intensities into the stand curves. The ratios of m6A/A were subsequently calculated.

Western Blotting

Proteins were extracted from frozen ileum mucosa by grinding with radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer and phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride. BCA assay kit was used to measure the protein concentrations. Thereafter, 40 μg of protein/lane was electrophoresed in 4–12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels followed by transfer to poly(vinylidene difluoride) membranes and blocking with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline Tween 20 buffer for 1 h. After blocking, the membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4 °C. The primary antibodies were β-actin (1:7000, 60008-1-AP; Proteintech, Rosemont, IL), METTL3 (1:1000, 15073-1-AP; Proteintech), and YTHDF2 (1:500, 24744-1-AP; Proteintech). The membranes were washed in TBST five times and were processed with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG, 1:10 000; Proteintech) for 90 min at room temperature. The blots were developed using an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Merck Millipore) followed by autoradiography. Images were recorded using a Luminescent Image Analyzer LAS-4000 system (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan) and were quantified by Image-Pro Plus 6.0. β-Actin was used as the internal standard to normalize the signals.

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean with standard error of mean (SEM) and analyzed by one-way analysis of variance using the SPSS 25.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Differences among group mean were determined by Tukey–Kramer multiple range test. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Growth Performance and Apparent Digestibility of Nutrients

Compared with the CON group, the average daily gain (ADG) was higher (P < 0.05) in the ANT and HRC groups (Table 1), the average daily feed intake (ADFI) was increased (P < 0.05) in the HRC group, and the feed conversion ratio (FCR) was lower (P < 0.05) in the ANT and LRC groups. Higher (P < 0.05) crude protein (CP) digestibility was found in the ANT group and higher (P < 0.05) crude fat (EE) digestibility was found in the ANT, HRC, LRC, and RES groups. Higher (P < 0.05) dry matter (DM) digestibility was found in the ANT and HRC groups. There was no difference among the ANT, HRC, LRC, RES, and CUR groups for the crude fiber (CF) and ash digestibility.

Table 1. Effects of Dietary Supplementary with Resveratrol and Curcumin on Growth Performance and Apparent Digestibility of Nutrients in Weaned Pigletsa,b,c.

| items | CON | ANT | HRC | LRC | RES | CUR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Performance | ||||||

| ADG (g/days) | 278.50 ± 9.40b | 316.00 ± 10.71a | 319.20 ± 10.29a | 296.50 ± 12.98ab | 301.60 ± 8.62ab | 303.50 ± 15.08ab |

| ADFI (g/days) | 480.30 ± 12.96b | 491.40 ± 7. 60ab | 508.30 ± 5.08a | 496.90 ± 5.92ab | 499.10 ± 6.05ab | 489.30 ± 5.42ab |

| FCR | 1.72 ± 0.02b | 1.56 ± 0.03a | 1.60 ± 0.05ab | 1.58 ± 0.06a | 1.66 ± 0.04ab | 1.64 ± 0.08ab |

| Apparent Digestibility of Nutrients (%) | ||||||

| crude protein | 79.00 ± 0.30b | 84.33 ± 3.06a | 83.33 ± 1.53b | 80.33 ± 2.52ab | 81.00 ± 2.00ab | 80.33 ± 1.53ab |

| crude fat | 69.04 ± 7.59b | 82.31 ± 6.94a | 80.33 ± 2.02a | 75.47 ± 2.63a | 77.90 ± 2.63a | 72.95 ± 3.48ab |

| crude fiber | 19.40 ± 1.25 | 20.14 ± 1.94 | 20.88 ± 1.93 | 20.36 ± 2.27 | 19.73 ± 2.71 | 20.12 ± 3.44 |

| ash | 71.03 ± 2.00 | 78.07 ± 4.08 | 76.44 ± 4.97 | 75.60 ± 4.48 | 76.87 ± 2.40 | 76.43 ± 6.67 |

| dry matter | 79.24 ± 3.23b | 82.75 ± 4.31a | 81.98 ± 2.17a | 80.26 ± 4.14ab | 80.79 ± 1.91ab | 80.12 ± 2.59ab |

Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 30/group. Different letters on the shoulder mark indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05), the same letter or no letter indicates that the difference is not significant (P ≥ 0.05).

ANT, control diet + 300 mg/kg antibiotics; CON, control diet; HRC, control diet + curcumin and resveratrol (300 mg/kg); LRC, control diet + curcumin and resveratrol (100 mg/kg); RES, control diet + 300 mg/kg resveratrol; CUR, control diet + 300 mg/kg curcumin.

ADG, average daily gain; ADFI, average daily feed intake; FCR, feed conversion ratio.

Intestinal Morphology

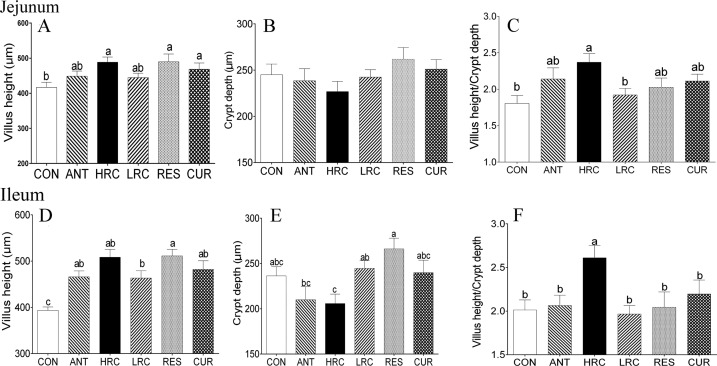

Compared with the CON group, the villus height of the jejunum was higher (P < 0.05) in the HRC, RES, and CUR groups (Figure 1A) but there was no difference among the ANT, HRC, LRC, RES, and CUR groups. No change in crypt depth was observed in the jejunum of piglets (Figure 1B). The villus height/crypt depth of the jejunum was increased (P < 0.05) in the HRC group compared to the CON and LRC groups (Figure 1C). Villus height of ileum (Figure 2A) was higher (P < 0.05) in the ANT, HRC, LRC, RES, and CUR groups and higher (P < 0.05) villus height/crypt depth of ileum (Figure 2C) was observed in the HRC group.

Figure 1.

Effects of dietary supplementation with resveratrol and curcumin on the mucosal morphology of the jejunum and ileum in weaned piglets. (A, D) Villus height, (B, E) crypt depth, (C, F) villus height/crypt depth ratio. The column and its bar represent the mean value and SEM, respectively. Different letters on the shoulder mark indicate significant differences (P < 0.05), and the same letter or no letter indicates that the difference is not significant (P ≥ 0.05). ANT, control diet + 300 mg/kg antibiotics; CON, control diet; HRC, control diet + curcumin and resveratrol (300 mg/kg); LRC, control diet + curcumin and resveratrol (100 mg/kg); RES, control diet + 300 mg/kg resveratrol; CUR, control diet + 300 mg/kg curcumin.

Figure 2.

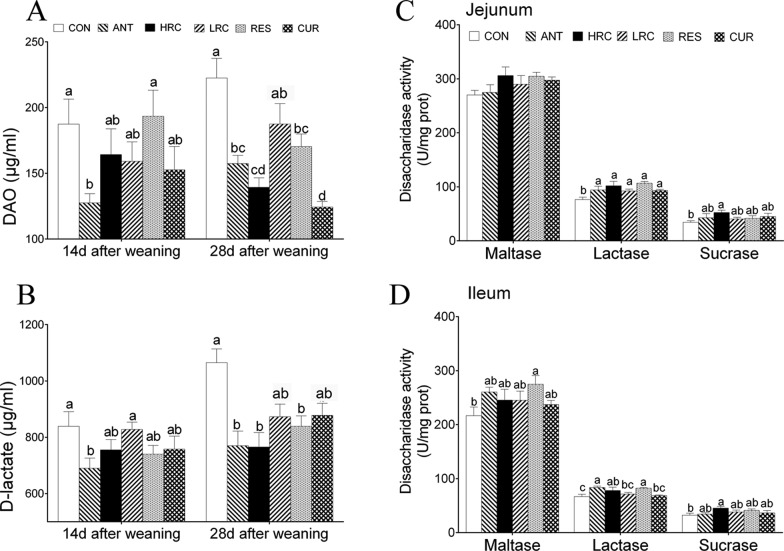

Effects of dietary supplementation with resveratrol and curcumin on the level of plasma diamine oxidase and d-lactate, and the activity of mucosa disaccharidase in weaned piglets. (A) The level of plasma d-lactate, (B) the level of plasma DAO, (C) jejunal disaccharidase activity, and (D) ileal disaccharidase activity. The column and its bar represent the mean value and SEM, respectively, n = 6/group. Different letters on the shoulder mark indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05), and the same letter or no letter indicates that the difference is not significant (P ≥ 0.05). ANT, control diet + 300 mg/kg antibiotics; CON, control diet; HRC, control diet + curcumin and resveratrol (300 mg/kg); LRC, control diet + curcumin and resveratrol (100 mg/kg); RES, control diet + 300 mg/kg resveratrol; CUR, control diet + 300 mg/kg curcumin.

Plasma d-Lactate Content and Diamine Oxidase Activity

We observed that plasma d-lactate was lower in the ANT group than that in the CON and LRC groups, and the activity of diamine oxidase (DAO) was decreased in the ANT group compared to the CON and RES groups at 14 days after weaning (P < 0.05) (Figure 2A). Piglets in the ANT, RES, and CUR groups showed a decreased level of both plasma d-lactate and activity of DAO compared to the CON group at 28 days after weaning (Figure 2B).

Intestinal Antioxidant Capacity and Disaccharidase Activity

The activity of lactase was higher in the ANT, HRC, LRC, RES, and CUR groups than that in the CON group in the jejunum (P < 0.05) (Figure 2C). In the ileum, the activity of lactase in the ANT, HRC, and RES groups was increased compared to that in the CON group (Figure 2D). In the jejunum and ileum, sucrase activity was higher (P < 0.05) in the HRC group than that in the other groups. We only observed increased maltase activity in the RES group in the ileum (P < 0.05).

Compared with the CON group, the content of GSH was higher (P < 0.05) in the ANT, HRC, LRC and RES groups in the jejunum (Table 2), and in the ANT, LRC, and RES groups in the ileum, respectively. The content of GSSG decreased in the HRC, RES and CUR groups in both the jejunum and ileum (P < 0.05). The levels of MDA were lower (P < 0.05) in the ANT, HRC, and CUR groups in the jejunum and also decreased in the ANT, HRC, LRC, RES, and CUR groups compared to the CON group in the ileum. We observed that higher (P < 0.05) GSH/GSSG ratio in the HRC, RES, and CUR groups in the jejunum and also in the HRC, LRC, RES, and CUR group in the ileum, respectively. The activity of SOD was increased (P < 0.05) in the HRC and RES groups in the jejunum but did not change in the ileum. The activity of T-AOC was higher in the ANT and RES groups compared to the CON, HRC, LRC, and CUR groups in the ileum (P < 0.05).

Table 2. Effects of Dietary Supplementation of Resveratrol and Curcumin on Intestinal Antioxidant Capacity of Weaned Pigletsa,b,c.

| items | CON | ANT | HRC | LRC | RES | CUR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jejunum | ||||||

| GSH (nmol/mg prot) | 1.96 ± 0.02c | 2.48 ± 0.04a | 2.62 ± 0.05a | 2.17 ± 0.06b | 2.24 ± 0.05b | 2.10 ± 0.03bc |

| GSSG (nmol/mg prot) | 0.17 ± 0.01a | 0.16 ± 0.01a | 0.13 ± 0.01b | 0.15 ± 0.01ab | 0.13 ± 0.01b | 0.13 ± 0.01b |

| GSH/GSSG | 12.03 ± 0.31c | 14.67 ± 0.26bc | 19.79 ± 1.01a | 14.79 ± 0.89bc | 16.79 ± 0.76b | 15.73 ± 0.43b |

| GSH-PX (U/mg prot) | 33.85 ± 1.06 | 36.05 ± 1.34 | 37.85 ± 0.47 | 34.50 ± 1.68 | 34.37 ± 2.61 | 35.90 ± 1.08 |

| MDA (nmol/mg prot) | 0.66 ± 0.05a | 0.55 ± 0.02b | 0.52 ± 0.03b | 0.57 ± 0.02ab | 0.62 ± 0.02ab | 0.54 ± 0.03b |

| SOD (U/mg prot) | 142.08 ± 12.08b | 162.15 ± 10.71ab | 170.96 ± 8.93a | 144.26 ± 5.77b | 170.88 ± 4.00a | 154.44 ± 4.46ab |

| T-AOC (U/mg prot) | 2.13 ± 0.09ab | 2.31 ± 0.06b | 2.59 ± 0.15a | 2.44 ± 0.04ab | 2.44 ± 0.04ab | 2.45 ± 0.08ab |

| Ileum | ||||||

| GSH (nmol/mg prot) | 1.93 ± 0.06b | 2.32 ± 0.08a | 2.28 ± 0.08ab | 2.46 ± 0.14a | 2.36 ± 0.03a | 2.26 ± 0.06ab |

| GSSG (nmol/mg prot) | 0.16 ± 0.01a | 0.13 ± 0.01bc | 0.13 ± 0.02bc | 0.13 ± 0.01b | 0.11 ± 0.01c | 0.12 ± 0.01bc |

| GSH/GSSG | 11.86 ± 0.33c | 13.77 ± 0.48bc | 17.08 ± 0.74ab | 16.84 ± 1.48ab | 17.67 ± 0.71a | 16.93 ± 0.51ab |

| GSH-PX (U/mg prot) | 30.91 ± 1.90 | 34.72 ± 1.18 | 36.32 ± 1.46 | 34.65 ± 1.07 | 36.38 ± 1.03 | 34.20 ± 1.60 |

| MDA (nmol/mg prot) | 0.68 ± 0.02a | 0.60 ± 0.05b | 0.53 ± 0.02b | 0.54 ± 0.02b | 0.62 ± 0.02b | 0.56 ± 0.03b |

| SOD (U/mg prot) | 137.56 ± 6.70 | 150.43 ± 4.92 | 168.30 ± 6.53 | 145.43 ± 8.34 | 161.88 ± 4.68 | 160.52 ± 14.10 |

| T-AOC (U/mg prot) | 2.02 ± 0.07b | 2.50 ± 0.05a | 2.48 ± 0.15ab | 2.45 ± 0.10ab | 2.60 ± 0.12a | 2.40 ± 0.14ab |

Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 6/group. Different letters on the shoulder mark indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05), the same letter or no letter indicates that the difference is not significant (P ≥ 0.05).

GSH-PX, glutathione peroxidase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; GSH, glutathione; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; MDA, malondialdehyde; T-AOC, total antioxidant capacity.

ANT, control diet + 300 mg/kg antibiotics; CON, control diet; HRC, control diet + curcumin and resveratrol (300 mg/kg); LRC, control diet + curcumin and resveratrol (100 mg/kg); RES, control diet + 300 mg/kg resveratrol; CUR, control diet + 300 mg/kg curcumin.

Messenger RNA Expression in the Intestine

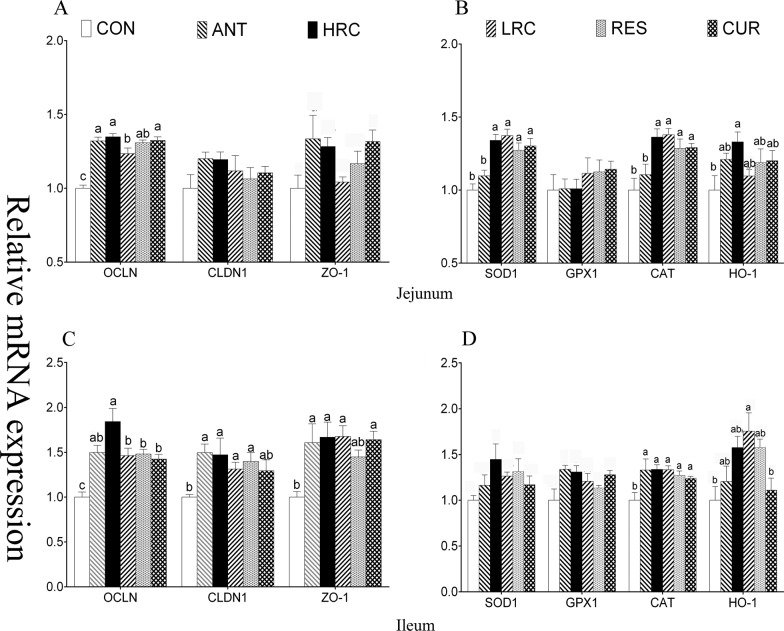

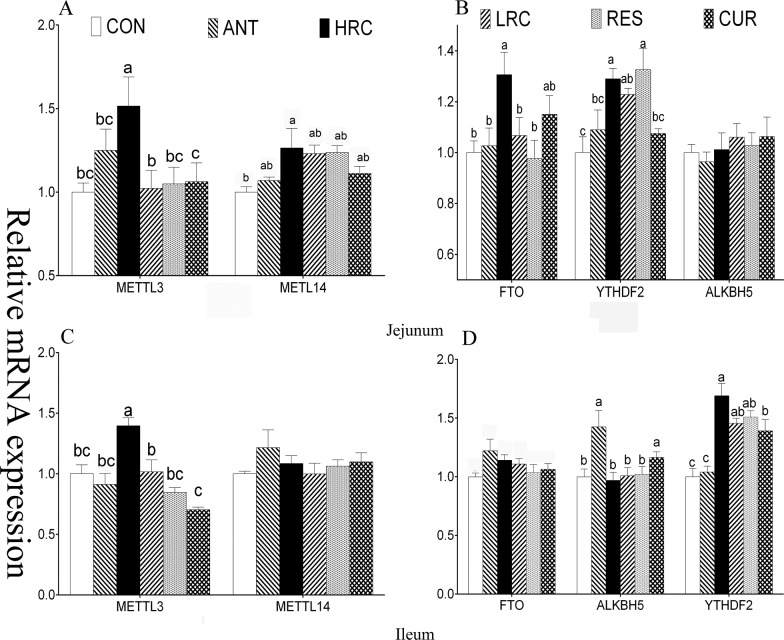

When compared with the CON group, the mRNA expression level of OCLN was increased (P < 0.05) in the ANT, HRC, LRC, RES, and CUR groups in the jejunum and ileum (Figure 3), CLDN1 was increased (P < 0.05) in the ANT, HRC, LRC, and RES groups in ileum, and ZO-1 was increased (P < 0.05) in the ANT, HRC, LRC, and CUR groups in ileum. Piglets in the HRC, LRC, RES, and CUR groups showed increased (P < 0.05) mRNA expression level of SOD1 in the jejunum, increased (P < 0.05) level of catalase (CAT) in the HRC, LRC, RES, and CUR groups in the jejunum and ileum, increased (P < 0.05) expression level of HO-1 in the HRC group in the jejunum, and in the LRC and CUR groups in the ileum. The mRNA expression level of METTL3 was higher (P < 0.05) in the HRC group in the jejunum and ileum (Figure 4), METTL14 and FTO were higher (P < 0.05) in the HRC group in jejunum, the ALKBH5 expression level was higher (P < 0.05) in the ileum of the ANT and CUR groups, and YTHDF2 was expressed at a high (P < 0.05) level in the HRC, LRC, and RES groups in the jejunum and the HRC, LRC, RES, and CUR groups in the ileum.

Figure 3.

Effects of dietary supplementation with resveratrol and curcumin on jejunum and ileum mucosal gene expression in the jejunum and ileum of weaned piglets, (A) mRNA expression level of jejunal tight junction protein, (B) mRNA expression level of jejunal antioxidant enzyme, (C) mRNA expression level of ileal tight junction protein, and (D) mRNA expression level of ileal antioxidant enzyme. The column and its bar represent the mean value and SEM, respectively; n = 6/group. Different letters on the shoulder mark indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05), and the same letter or no letter indicates that the difference is not significant (P ≥ 0.05). OCLN, occludin; CLDN1, claudin 1; ZO-1, zonula occluden; SOD1, superoxide dismutase 1; GPX, glutathione peroxidase 1; CAT, catalase; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1. ANT, control diet + 300 mg/kg antibiotics; CON, control diet; HRC, control diet + curcumin and resveratrol (300 mg/kg); LRC, control diet + curcumin and resveratrol (100 mg/kg); RES, control diet + 300 mg/kg resveratrol; CUR, control diet + 300 mg/kg curcumin.

Figure 4.

Effects of dietary supplementation with resveratrol and curcumin on jejunum and ileum mucosa gene expression in weaned piglets. (A) mRNA expression level of methyltransferase in the jejunum. (B) mRNA expression level of demethylases and YTHDF2 in the jejunum. (C) mRNA expression level of demethylase in the ileum. (D) mRNA expression level of demethylases and YTHDF2 in the ileum. METTL3, methyltransferase-like 3; METTL14, methyltransferase-like 14; FTO, fat mass and obesity-associated protein; ALKBH5, alkB homolog 5; YTHDF2, YTH N6-methyladenosine RNA binding protein 2. The column and its bar represent the mean value and SEM, respectively; n = 6/group. Different letters on the shoulder mark indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05), and the same letter or no letter indicates that the difference is not significant (P ≥ 0.05). ANT, control diet + 300 mg/kg antibiotics; CON, control diet; HRC, control diet + curcumin and resveratrol (300 mg/kg); LRC, control diet + curcumin and resveratrol (100 mg/kg); RES, control diet + 300 mg/kg resveratrol; CUR, control diet + 300 mg/kg curcumin.

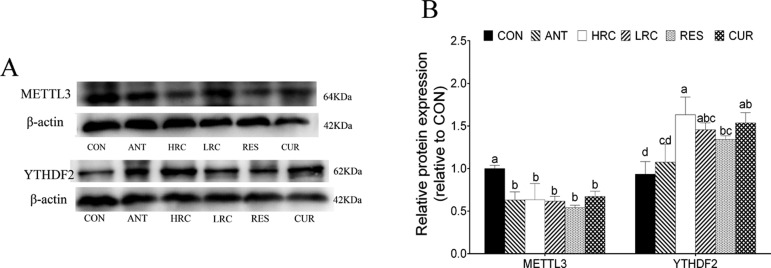

Protein Expression of Intestine

Compared with the CON group, the protein expression level of METTL3 was decreased in the ANT, HRC, LRC, RES, and CUR groups in the ileum (Figure 5), and the protein expression level of YTHDF2 was increased in the HRC, LRC, RES, and CUR groups in the ileum.

Figure 5.

Protein expressions of METTL3 and YTHDF2 in ileum mucosa normalized to β-actin. (A) METTL3 and YTHDF2 protein expressions, as detected by western blot analysis. (B) Relative protein expressions of METTL3 and YTHDF2. The column and its bar represent the mean value and SEM, respectively; n = 4/group. Different letters on the shoulder mark indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05), and the same letter or no letter indicates that the difference is not significant (P ≥ 0.05). ANT, control diet + 300 mg/kg antibiotics; CON, control diet; HRC, control diet + curcumin and resveratrol (300 mg/kg); LRC, control diet + curcumin and resveratrol (100 mg/kg); RES, control diet + 300 mg/kg resveratrol; CUR, control diet + 300 mg/kg curcumin.

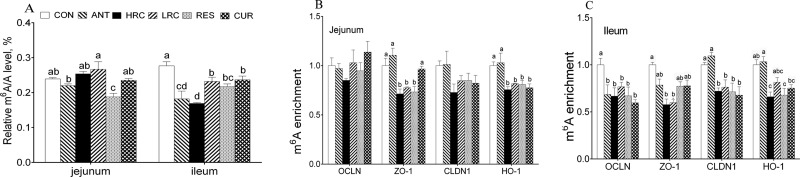

m6A Level and m6A Enrichment in Transcript

The content of m6A was decreased in the jejunum in RES groups compared to that of the other groups (Figure 6A). In the ileum, the m6A levels of the ANT, HRC, LRC, RES, and CUR groups were decreased when compared with that of the CON group. In particular, the combination of resveratrol and curcumin at high doses further decreased the content of m6A in the ileum (P < 0.05).

Figure 6.

m6A/A level and m6A enrichment in the intestine of weaned piglets. (A) Relative m6A level of the intestinal mucosa; (B) jejunal m6A enrichment; and (C) ileum m6A enrichment. The column and its bar represent the mean value and SEM, respectively; n = 3/group. Different letters on the shoulder mark indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05), and the same letter or no letter indicates that the difference is not significant (P ≥ 0.05). ANT, control diet + 300 mg/kg antibiotics; CON, control diet; HRC, control diet + curcumin and resveratrol (300 mg/kg); LRC, control diet + curcumin and resveratrol (100 mg/kg); RES, control diet + 300 mg/kg resveratrol; CUR, control diet + 300 mg/kg curcumin.

In the jejunum, supplementation of resveratrol and curcumin significantly decreased the m6A enrichment in ZO-1 and HO-1 mRNA compared to the CON and ANT groups (P < 0.05) in the jejunum but there was no change in OCLN and CLDN1 gene (Figure 6B). In the ileum, the ANT, RES, and CUR additional group showed a decreased level of the m6A enrichment in OCLN and ZO-1 mRNA compared to the CON group (Figure 6A). The m6A enrichment of CLDN1 and HO-1 gene was lower (P < 0.05) in the HRC, LRC, RES, and CUR groups than the CON and ANT groups, but there was no difference (P > 0.05) between the CON and ANT groups in the ileum (Figure 6B).

Discussion

Resveratrol and curcumin may have an impact on the weaned piglet growth performance and the intestinal mucosal barrier functions, as well as the gene expression. Here, we observed that dietary supplementation with resveratrol and curcumin improved piglet ADG, ADFI, and FCR, influenced the apparent digestibility of nutrients, promoted intestinal mucosa growth, and improved intestinal mucosal integrity in weaning piglets, particularly in combination of resveratrol and curcumin at high doses. In addition, the gene expression levels of intestinal antioxidants gene and tight junction protein gene were increased, and the relative m6A/A level and the m6A enrichment were decreased in the ileum. Thus, we hypothesized that dietary supplementation with resveratrol and curcumin can decrease the N6-methyladenosine level in weaned piglet intestine, then influence intestinal mucosa permeability and improve intestinal antioxidative ability, and, ultimately, affect their growth.

Accumulating evidence has identified the beneficial effects of resveratrol and curcumin on animal health and disease, including an increase in growth performance and improvement in intestinal function,3,27,28 but these functions are utility limited because of low bioavailability. For the first time, we determined the effect of a combination of resveratrol and curcumin on growth performance and intestinal function in weaning piglets. In the present study, low levels of resveratrol and curcumin in combination did not exert beneficial effects on growth and intestinal health in weaning piglets; however, the combination of resveratrol and curcumin at high doses increased growth performance, antioxidant activity, and intestinal mucosal integrity, suggesting that resveratrol and curcumin may have synergistic effects. Low bioavailability also limits the applications of resveratrol and curcumin because of their similar characteristics: extremely hydrophobic, poor absorption, and fast systemic elimination.6,7 However, researchers have found that the combined use of resveratrol and curcumin may have mutual effects on improving their bioavailability.29,30 Resveratrol and curcumin should combine with plasma proteins to exert their functions because they are extremely hydrophobic; however, curcumin and resveratrol can improve the content of plasma protein, which may be the underlying mechanism of how they exert their mutual effects.31 In addition, in our previous study, we found that resveratrol and curcumin can regulate intestinal bacteria in weaned piglets,32 and gut microbiota plays an important role in curcumin and resveratrol metabolism and biotransformation. Probiotics may have beneficial effects on the mucosa, and33,34 better mucosa environment also helps resveratrol and curcumin absorption. In addition, the present data showed that beneficial effects of resveratrol and curcumin on the intestinal function and gene expression in the ileum are better than those in the jejunum, which may be due to the higher concentration of resveratrol and its metabolite in the ileum than that in the jejunum.35

N6-methyladenine (m6A), as the most prevalent internal RNA methylation in eukaryotic mRNA, plays critical roles in regulating the expression of genes in fundamental cellular processes, including pri-mRNA splicing, mRNA nuclear transport, molecular stability, translation, and subcellular localization. In addition, m6A methylation is involved in diverse physiological functions, including obesity,36 immunoregulation, circadian rhythm,26 cellular differentiation,37 antitumor,38 and other human diseases.39 Interestingly, due to the dynamic and reversible nature of m6A modification, nutritional challenges, such as high-fat diet, dietary fasted state, and supplementation of the diet with betaine and cycloleucine, have been shown to affect the m6A RNA methylation patterns, altering the gene expression.20 Furthermore, resveratrol and curcumin can affect the nutrient absorbance by affecting the intestinal flora,40,41 which may have a potential connection with m6A. Using mass spectrometry, we found that the combination of resveratrol and curcumin decreased the content of m6A in the intestinal mucosal of weaning piglets. Decrease of m6A may be associated with inhibition of oxidative stress by resveratrol and curcumin since oxidative or heat stress can increase the m6A levels.15 Moreover, the effects of resveratrol and curcumin on m6A methylation may be associated with changes in microRNA since increasing evidence indicates that curcumin changes the expression profiles of microRNA in vivo and in vitro,9 and that the formation of m6A is modulated by microRNAs through regulating METTL3 selectively binding to mRNA substrates.42 We also found that the levels of m6A on OCLN, CLDN1, ZO-1, and HO-1 transcript reduced in the intestinal mucosal of weaning piglets. Decrease of m6A modification on genes promotes mRNA stability,43 leading to upregulation of gene expression, which is consistent with the expression of OCLN, CLDN1, ZO-1, and HO-1 mRNA.

Interestingly, we also found that the level of m6A/A was decreased in the ANT group; the underlying mechanism might be that antibiotics inhibit the proliferation of Gram-negative bacteria. After weaning, Gram-negative bacteria proliferate in large numbers, and the impaired intestinal epithelium leads to the release of endotoxin into the intestinal mucosa and systematic circulation and then accumulates in the liver.44 Researchers have found that intraperitoneal injection of lipopolysaccharide leads to an increased level of liver m6A in chicken45 and weaned piglets.21 The decreased intestinal bacterial population may be one of the causes of decreased m6A levels in the intestinal mucosa.

In conclusion, dietary supplementation with resveratrol and curcumin can enhance the growth performance of weaned piglets, the apparent nutrient digestibility, and can improve intestinal mucosal integrity, particularly in the group treated with the combination of resveratrol and curcumin at high doses. Furthermore, resveratrol and curcumin can decrease the content of mucosa m6A, which may promote mRNA stability, leading to an increase in the gene expression of tight junction proteins and antioxidant gene. The beneficial effects of resveratrol and curcumin still need further investigation, and our findings may be helpful in exploring a new natural product as an alternative antibiotic in healthcare products.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31872391 and 31572418) and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (No. BK 20161446).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- RES

resveratrol

- CUR

curcumin

- METTL3

methyltransferase-like 3

- METTL14

methyltransferase-like 14

- ALKBH5

alkB homolog 5

- FTO

fat mass and obesity-associated protein

- YTHDF

YTH family protein

- HO-1

heme oxygenase-1

- OCLN

occludin

- CLDN

claudin

- ZO-1

zonula occluden-1

- ADG

average daily gain

- ADFI

average daily feed intake

- FCR

feed conversion ratio

- GSH-PX

glutathione peroxidase

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- GSH

glutathione

- GSSG

oxidized glutathione

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.9b02236.

Composition and nutrient levels of the basal diet (Table S1); primer sequence for qRT-PCR used in this paper (Table S2); primer sequence for MeRIP-PCR used in this paper (Table S3) (PDF)

Author Contributions

† Z.G. and W.W. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Suzuki T. Regulation of intestinal epithelial permeability by tight junctions. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013, 70, 631–659. 10.1007/s00018-012-1070-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; Su W.; Ying Z.; Chen Y.; Zhou L.; Li Y.; Zhang J.; Zhang L.; Wang T. N-acetylcysteine attenuates intrauterine growth retardation-induced hepatic damage in suckling piglets by improving glutathione synthesis and cellular homeostasis. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 327–338. 10.1007/s00394-016-1322-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N.; Han Q.; Wang G.; Ma W. P.; Wang J.; Wu W. X.; Guo Y.; Liu L.; Jiang X. Y.; Xie X. L.; Jiang H. Q. Resveratrol Protects Oxidative Stress-Induced Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Dysfunction by Upregulating Heme Oxygenase-1 Expression. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2016, 61, 2522–2534. 10.1007/s10620-016-4184-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J.; Niu Y.; Wang F.; Wang C.; Cui T.; Bai K.; Zhang J.; Zhong X.; Zhang L.; Wang T. Dietary curcumin supplementation attenuates inflammation, hepatic injury and oxidative damage in a rat model of intra-uterine growth retardation. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 537–548. 10.1017/s0007114518001630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel K. R.; Scott E.; Brown V. A.; Gescher A. J.; Steward W. P.; Brown K. Clinical trials of resveratrol. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1215, 161–169. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand P.; Kunnumakkara A. B.; Newman R. A.; Aggarwal B. B. Bioavailability of curcumin: problems and promises. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2007, 4, 807–818. 10.1021/mp700113r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amri A.; Chaumeil J. C.; Sfar S.; Charrueau C. Administration of resveratrol: What formulation solutions to bioavailability limitations?. J. Controlled Release 2012, 158, 182–193. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briskey D.; Sax A.; Mallard A. R.; Rao A. Increased bioavailability of curcumin using a novel dispersion technology system (LipiSperse). Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 2087–2097. 10.1007/s00394-018-1766-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momtazi A. A.; Shahabipour F.; Khatibi S.; Johnston T. P.; Pirro M.; Sahebkar A. Curcumin as a MicroRNA Regulator in Cancer: A Review. Rev. Physiol., Biochem. Pharmacol. 2016, 171, 1–38. 10.1007/112_2016_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunnumakkara A. B.; Bordoloi D.; Harsha C.; Banik K.; Gupta S. C.; Aggarwal B. B. Curcumin mediates anticancer effects by modulating multiple cell signaling pathways. Clin. Sci. 2017, 131, 1781–1799. 10.1042/CS20160935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Yue Y.; Han D.; Wang X.; Fu Y.; Zhang L.; Jia G.; Yu M.; Lu Z.; Deng X.; Dai Q.; Chen W.; He C. A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 10, 93–95. 10.1038/nchembio.1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia G.; Fu Y.; Zhao X.; Dai Q.; Zheng G.; Yang Y.; Yi C.; Lindahl T.; Pan T.; Yang Y. G.; He C. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 7, 885–887. 10.1038/nchembio.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Lu Z.; Gomez A.; Hon G. C.; Yue Y.; Han D.; Fu Y.; Parisien M.; Dai Q.; Jia G.; Ren B.; Pan T.; He C. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature 2014, 505, 117–120. 10.1038/nature12730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominissini D.; Moshitch-Moshkovitz S.; Salmon-Divon M.; Amariglio N.; Rechavi G. Transcriptome-wide mapping of N(6)-methyladenosine by m(6)A-seq based on immunocapturing and massively parallel sequencing. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 176–189. 10.1038/nprot.2012.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J.; Wan J.; Gao X.; Zhang X.; Jaffrey S. R.; Qian S. B. Dynamic m(6)A mRNA methylation directs translational control of heat shock response. Nature 2015, 526, 591–594. 10.1038/nature15377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G.; Dahl J. A.; Niu Y.; Fedorcsak P.; Huang C. M.; Li C. J.; Vagbo C. B.; Shi Y.; Wang W. L.; Song S. H.; Lu Z.; Bosmans R. P.; Dai Q.; Hao Y. J.; Yang X.; Zhao W. M.; Tong W. M.; Wang X. J.; Bogdan F.; Furu K.; Fu Y.; Jia G.; Zhao X.; Liu J.; Krokan H. E.; Klungland A.; Yang Y. G.; He C. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 18–29. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Li Y.; Toth J. I.; Petroski M. D.; Zhang Z.; Zhao J. C. N6-methyladenosine modification destabilizes developmental regulators in embryonic stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 191–198. 10.1038/ncb2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng H.; Huang H.; Wu H.; Qin X.; Zhao B. S.; Dong L.; Shi H.; Skibbe J.; Shen C.; Hu C.; Sheng Y.; Wang Y.; Wunderlich M.; Zhang B.; Dore L. C.; Su R.; Deng X.; Ferchen K.; Li C.; Sun M.; Lu Z.; Jiang X.; Marcucci G.; Mulloy J. C.; Yang J.; Qian Z.; Wei M.; He C.; Chen J. METTL14 Inhibits Hematopoietic Stem/Progenitor Differentiation and Promotes Leukemogenesis via mRNA m(6)A Modification. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 22, 191.e9–205.e9. 10.1016/j.stem.2017.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Zhu L.; Chen J.; Wang Y. mRNA m(6)A methylation downregulates adipogenesis in porcine adipocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 459, 201–207. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Yang J.; Zhu Y.; Liu Y.; Shi X.; Yang G. Mouse Maternal High-Fat Intake Dynamically Programmed mRNA m(6)A Modifications in Adipose and Skeletal Muscle Tissues in Offspring. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1336 10.3390/ijms17081336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu N.; Li X.; Yu J.; Li Y.; Wang C.; Zhang L.; Wang T.; Zhong X. Curcumin Attenuates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Hepatic Lipid Metabolism Disorder by Modification of m 6 A RNA Methylation in Piglets. Lipids 2018, 53, 53–63. 10.1002/lipd.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austreng E.; Storebakken T.; Thomassen M. S.; Refstie S.; Thomassen Y. Evaluation of selected trivalent metal oxides as inert markers used to estimate apparent digestibility in salmonids. Aquaculture 2000, 188, 65–78. 10.1016/S0044-8486(00)00336-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh A. M.; Sweeney T.; O’Shea C. J.; Doyle D. N.; O’Doherty J. V. Effect of supplementing varying inclusion levels of laminarin and fucoidan on growth performance, digestibility of diet components, selected faecal microbial populations and volatile fatty acid concentrations in weaned pigs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2013, 183, 151–159. 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2013.04.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su W.; Zhang H.; Ying Z.; Li Y.; Zhou L.; Wang F.; Zhang L.; Wang T. Effects of dietary l-methionine supplementation on intestinal integrity and oxidative status in intrauterine growth-retarded weanling piglets. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 2735–2745. 10.1007/s00394-017-1539-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard L. A. Francis Gano Benedict--a biographical sketch (1870–1957). J. Nutr. 1969, 98, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong X.; Yu J.; Frazier K.; Weng X.; Li Y.; Cham C. M.; Dolan K.; Zhu X.; Hubert N.; Tao Y.; Lin F.; Martinez-Guryn K.; Huang Y.; Wang T.; Liu J.; He C.; Chang E. B.; Leone V. Circadian Clock Regulation of Hepatic Lipid Metabolism by Modulation of m(6)A mRNA Methylation. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 1816.e4–1828.e4. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.10.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W. B.; Wang Y. Y.; Meng F. S.; Zhang Q. H.; Zeng J. Y.; Xiao L. P.; Yu X. P.; Peng D. D.; Su L.; Xiao B.; Zhang Z. S. Curcumin protects intestinal mucosal barrier function of rat enteritis via activation of MKP-1 and attenuation of p38 and NF-kappaB activation. PLoS One 2010, 5, e12969 10.1371/journal.pone.0012969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N.; Wang G.; Hao J.; Ma J.; Wang Y.; Jiang X.; Jiang H. Curcumin ameliorates hydrogen peroxide-induced epithelial barrier disruption by upregulating heme oxygenase-1 expression in human intestinal epithelial cells. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2012, 57, 1792–1801. 10.1007/s10620-012-2094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi F.; Moeeni M. Study on the interactions of trans-resveratrol and curcumin with bovine α-lactalbumin by spectroscopic analysis and molecular docking. Mater. Sci. Eng., C 2015, 50, 358–366. 10.1016/j.msec.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakibaei S.; Mobasheri A.; Buhrmann C. Curcumin synergizes with resveratrol to stimulate the MAPK signaling pathway in human articular chondrocytes in vitro. Genes Nutr. 2011, 6, 171. 10.1007/s12263-010-0179-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey K. B.; Rizvi S. I. Resveratrol may protect plasma proteins from oxidation under conditions of oxidative stress in vitro. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2010, 21, 909–913. 10.1590/S0103-50532010000500020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gan Z.; Wei W.; Li Y.; Wu J.; Zhao Y.; Zhang L.; Wang T.; Zhong X. Curcumin and Resveratrol Regulate Intestinal Bacteria and Alleviate Intestinal Inflammation in Weaned Piglets. Molecules 2019, 24, 1220 10.3390/molecules24071220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White R.; Atherly T.; Guard B.; Rossi G.; Wang C.; Mosher C.; Webb C.; Hill S.; Ackermann M.; Sciabarra P.; Allenspach K.; Suchodolski J.; Jergens A. E. Randomized, controlled trial evaluating the effect of multi-strain probiotic on the mucosal microbiota in canine idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. Gut Microbes 2017, 8, 451–466. 10.1080/19490976.2017.1334754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiely C. J.; Pavli P.; O’Brien C. L. The role of inflammation in temporal shifts in the inflammatory bowel disease mucosal microbiome. Gut Microbes 2018, 9, 477–485. 10.1080/19490976.2018.1448742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azorín-Ortuño M.; Yáñez-Gascón M. J.; Vallejo F.; Pallarés F. J.; Larrosa M.; Lucas R.; Morales J. C.; Tomás-Barberán F. A.; García-Conesa M. T.; Espín J. C. Metabolites and tissue distribution of resveratrol in the pig. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2011, 55, 1154–1168. 10.1002/mnfr.201100140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church C.; Moir L.; McMurray F.; Girard C.; Banks G. T.; Teboul L.; Wells S.; Brüning J. C.; Nolan P. M.; Ashcroft F. M.; Cox R. D. Overexpression of Fto leads to increased food intake and results in obesity. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 1086–1092. 10.1038/ng.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista P. J.; Molinie B.; Wang J.; Qu K.; Zhang J.; Li L.; Bouley D. M.; Lujan E.; Haddad B.; Daneshvar K.; Carter A. C.; Flynn R. A.; Zhou C.; Lim K. S.; Dedon P.; Wernig M.; Mullen A. C.; Xing Y.; Giallourakis C. C.; Chang H. Y. m(6)A RNA modification controls cell fate transition in mammalian embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 15, 707–719. 10.1016/j.stem.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J. Z.; Yang F.; Zhou C. C.; Liu F.; Yuan J. H.; Wang F.; Wang T. T.; Xu Q. G.; Zhou W. P.; Sun S. H. METTL14 suppresses the metastatic potential of hepatocellular carcinoma by modulating N6-methyladenosine-dependent primary MicroRNA processing. Hepatology 2017, 529–543. 10.1002/hep.28885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geula S.; Moshitch-Moshkovitz S.; Dominissini D.; Mansour A. A.; Kol N.; Salmon-Divon M.; Hershkovitz V.; Peer E.; Mor N.; Manor Y. S.; Ben-Haim M. S.; Eyal E.; Yunger S.; Pinto Y.; Jaitin D. A.; Viukov S.; Rais Y.; Krupalnik V.; Chomsky E.; Zerbib M.; Maza I.; Rechavi Y.; Massarwa R.; Hanna S.; Amit I.; Levanon E. Y.; Amariglio N.; Stern-Ginossar N.; Novershtern N.; Rechavi G.; Hanna J. H. Stem cells. m6A mRNA methylation facilitates resolution of naive pluripotency toward differentiation. Science 2015, 347, 1002–1006. 10.1126/science.1261417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solano-Aguilar G.; Shea-Donohue T.; Madden K. B.; Quinoñes A.; Beshah E.; Lakshman S.; Xie Y.; Dawson H.; Urban J. F. Bifidobacterium animalis subspecies lactis modulates the local immune response and glucose uptake in the small intestine of juvenile pigs infected with the parasitic nematode Ascaris suum. Gut Microbes 2018, 9, 422–436. 10.1080/19490976.2018.1460014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings J. H.; Macfarlane G. T. Role of intestinal bacteria in nutrient metabolism. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 16, 3–11. 10.1016/S0261-5614(97)80252-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T.; Hao Y. J.; Zhang Y.; Li M. M.; Wang M.; Han W.; Wu Y.; Lv Y.; Hao J.; Wang L.; Li A.; Yang Y.; Jin K. X.; Zhao X.; Li Y.; Ping X. L.; Lai W. Y.; Wu L. G.; Jiang G.; Wang H. L.; Sang L.; Wang X. J.; Yang Y. G.; Zhou Q. m(6)A RNA methylation is regulated by microRNAs and promotes reprogramming to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 16, 289–301. 10.1016/j.stem.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roundtree I. A.; Evans M. E.; Pan T.; He C. Dynamic RNA Modifications in Gene Expression Regulation. Cell 2017, 169, 1187–1200. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A. P.; Schultze A. E.; Holdan W. L.; Buchweitz J. P.; Roth R. A.; Ganey P. E. Lipopolysaccharide-induced hepatic injury is enhanced by polychlorinated biphenyls. Environ. Health Perspect. 1996, 104, 634–640. 10.1289/ehp.96104634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Guo F.; Zhao R. Hepatic expression of FTO and fatty acid metabolic genes changes in response to lipopolysaccharide with alterations in m(6)A modification of relevant mRNAs in the chicken. Br. Poult. Sci. 2016, 57, 628–635. 10.1080/00071668.2016.1201199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.