ABSTRACT

Introduction:

Many published studies have estimated the association of rs2435357 and rs1800858 polymorphisms in the proto-oncogene rearranged during transfection (RET) gene with Hirschsprung disease (HSCR) risk. However, the results remain inconsistent and controversial.

Aim:

To perform a meta-analysis get a more accurate estimation of the association of rs2435357 and rs1800858 polymorphisms in the RET proto-oncogene with HSCR risk.

Methods:

The eligible literatures were searched by PubMed, Google Scholar, EMBASE, and Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) up to June 30, 2018. Summary odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to evaluate the susceptibility to HSCR.

Results:

A total of 20 studies, including ten (1,136 cases 2,420 controls) for rs2435357 and ten (917 cases 1,159 controls) for rs1800858 were included. The overall results indicated that the rs2435357 (allele model: OR=0.230, 95% CI 0.178-0.298, p=0.001; homozygote model: OR=0.079, 95% CI 0.048-0.130, p=0.001; heterozygote model: OR=0.149, 95% CI 0.048-0.130, p=0.001; dominant model: OR=0.132, 95% CI 0.098-0.179, p=0.001; and recessive model: OR=0.239, 95% CI 0.161-0.353, p=0.001) and rs1800858 (allele model: OR=5.594, 95% CI 3.653-8.877, p=0.001; homozygote model: OR=8.453, 95% CI 3.783-18.890, p=0.001; dominant model: OR=3.469, 95% CI 1.881-6.396, p=0.001; and recessive model: OR=6.120, 95% CI 3.608-10.381, p=0.001) polymorphisms were associated with the increased risk of HSCR in overall.

Conclusions:

The results suggest that the rs2435357 and rs1800858 polymorphisms in the RET proto-oncogene might be associated with HSCR risk.

HEADINGS: Hirschsprung disease, Polymorphism, Single Nucleotide, Meta-Analysis

RESUMO

Introdução:

Muitos estudos publicados estimaram a associação dos polimorfismos rs2435357 e rs1800858 do proto-oncogene rearranjado durante a transfecção (RET) com o risco de doença por Hirschsprung (HSCR). No entanto, os resultados permanecem inconsistentes e controversos.

Objetivo:

Realizar metanálise para obter estimativa mais precisa da associação dos polimorfismos rs2435357 e rs1800858 no proto-oncogene RET com risco de HSCR.

Método:

A literatura elegível foi pesquisada pelo PubMed, Google Scholar, EMBASE e CNKI até 30 de junho de 2018.

Resultados:

Um total de 20 estudos, incluindo dez (1.136 casos 2.420 controles) para rs2435357 e dez (917 casos 1.159 controles) para rs1800858 foram incluídos. Os resultados globais indicaram que o rs2435357 (modelo alelo: OR=0,230, IC 95% 0,178-0,298, p=0,001; modelo homozigoto: OR=0,079, IC 95% 0,048-0,130, p=0,001; modelo heterozigoto: OR=0,149 , IC 95% 0,048-0,130, p=0,001, modelo dominante: OR=0,132, IC 95% 0,098-0,179, p=0,001 e modelo recessivo: OR=0,239, IC 95% 0,161-0,353, p=0,001) e rs1800858 (modelo alelo: OR=5,594, IC 95% 3,653-8,877, p=0,001; modelo homozigoto: OR=8,453, IC 95% 3,783-18,890, p=0,001; modelo dominante: OR=3,469, IC 95% 1,881- 6,396, p=0,001 e modelo recessivo: OR=6,120, 95% CI 3,608-10,381, p=0,001) polimorfismos foram associados com o aumento do risco de HSCR em geral.

Conclusões:

Os resultados sugerem que os polimorfismos rs2435357 e rs1800858 no proto-oncogene RET podem estar associados ao HSCR.

DESCRITORES: Doença de Hirschsprung, Polimorfismo de nucleotídeo único, Metanálise

INTRODUCTION

Hirschsprung disease (HSCR), also known as congenital megacolon, is a life-threatening birth defect characterized by the absence of enteric ganglia in the submucosal and myenteric plexuses of the gastrointestinal tract 6 . It´s incidence varies from 1:5,000 to 1:10,000 live births with an overall male to female ratio of 3:1 to 5:1, particularly in those with short segments 16 , 21 . The diagnosis is established in 15% within the first month of life, in 40-50% in the first three months, in 60% at the end of the first year of age, and in 85% by four years 7 . The exact mechanism of HSCR is unknown, but it is clear that both genetic and environmental factors are involved 6 . Trisomy chromosome 21 is the most frequent chromosomal abnormality (>90% cases) associated with HSCR disease 1 . Furthermore, it is associated with other congenital malformations in 5%-32% of cases including gastrointestinal tract, by CNS anomalies, hearing impairment and congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract 28 , 31 . Perinatal and environmental risk factors for HSCR, such as vitamin A, maternal age, obesity, parity, hypothyroidism during pregnancy, medical drug use have been sparsely studied; however, the results have not been consistent 15 , 22 , 43 .

HSCR can be inherited as an autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive and even as a polygenic disorder 1 . However, approximately in 30% of cases, it is associated with other malformations 8 . Genetic association analyses have identified 12 susceptibility loci including EDNRB, EDN3, GDNF, NTN, SOX10, PHOX2B, ECE1, KIAA1279/KBP, ZFHX1B, TTF-1 and NRG1 13 . However, variations in most of these loci are found mostly in the syndromic cases, in which HSCR is associated with other congenital malformation 1 , 8 . Linkage analyses of multiplex HSCR families established that the proto-oncogene rearranged during transfection (RET) is the major susceptibility gene to its development 8 . RET is a trans-membrane tyrosine kinase receptor which also involved in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN 2), causing medullary thyroid carcinoma, pheochromocytoma and primary hyperparathyroidism 18 , 25 . Among the variations of RET gene, rs2435357 and rs1800858 polymorphisms, locating in intron 1 and exon 2 of the RET gene, respectively, have been wildly investigated in HSCR. However, the results from different studies are controversial 8 .

Therefore, we carried out current systemic review and meta-analysis to clarify the associations of the SNP rs2435357 and rs1800858 with susceptibility to HSCR.

METHOD

Literature search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed using PubMed, EMBASE, Google scholar, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chinese Biomedical, WanFang and VIP database to identify all eligible studies evaluating the association of the RET rs2435357 and rs1800858 polymorphisms with HSCR risk up to June 30, 2018. The key words were as follows: (‘’Hirschsprung disease’’ OR ‘’HSCR’’ OR ‘’congenital megacolon’’) AND (‘’Rearrange during Transfection’’ OR ‘’RET Proto-oncogene’’ OR ‘’Proto-Oncogene C-Ret’’ OR ‘’RET gene’’ OR ‘’Cadherin-Related Family Member 16’’ OR ‘’Cadherin Family Member 12’’) AND (‘’rs1800858’’ OR ‘’c.135G>A’’ OR ‘’Ala45Ala’’) AND (‘’rs2435357’’ OR ‘’IVS1+9277C>T’’ OR ‘’c.73+9277C>T’’) AND (“polymorphism” OR “SNPs” OR “variation” OR “locus” OR “mutation”). The search was limited to human studies and published studies. In addition, the references list of relevant case-control studies and reviews were manually searched to identify any additional eligible studies. If two or more studies had the same or overlapping data, only the study with the largest sample or most recently published study was included in the meta-analysis.

Data collection

The data from the relevant published studies were extracted independently by two of the authors and entered them in a customized questionnaire. Then, the extracted data were compared, and disagreements were resolved through a discussion between the two researchers. For each eligible study, the following data were extracted: first author’s name, publication year, country of origin, ethnicity, genotyping methods, source of controls (population-based and hospital-based), case and control numbers, genotype frequency of SNPs, minor allele frequency in controls, and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in controls. The ethnicity was divided into Asian and Caucasian or others. In addition, studies was performed on different populations were considered as independent studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Selected studies were included in the meta-analysis if they met the following criteria: 1) case-control or cohort studies; 2) evaluating the association of the rs2435357 and rs1800858 polymorphisms of RET gene with susceptibility to HSCR; 3) studies with sufficient data to perform a meta-analysis. Accordingly, studies with the following characteristics were excluded: 1) not case-control or cohort study; 2) no control population; 3) studies with insufficient available data or lacking of genotypes distribution data; 4) abstracts, comments, case reports, letters, editorials, reviews, and systematic reviews; 5) published studies containing duplicate data.

Statistical analysis

The strength of association of RET rs2435357 and rs1800858 polymorphisms with HSCR risk was measured by odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical significance of the summary OR was determined using the Z-test. We used five models to evaluate associations of the RET rs2435357 and rs1800858 polymorphisms with HSCR risk including: allele model (B vs. A), homozygous model (BB vs. AA), heterozygous model (BB vs. BA), dominant model (BB+BA vs. AA), and recessive model (BB vs. AA+BA). The heterogeneity between studies was evaluated by chi-squared based Q test, in which a p-value less than <0.05 was considered obvious heterogeneity. In addition, the I2 value was used to test the degree of heterogeneity, in which I2<25%, no heterogeneity; I2 25-50%, moderate heterogeneity; I2>50%, large or extreme heterogeneity 17 . The fixed effects model was used to pool ORs and 95% confidential interval (CI) when there was no significant heterogeneity. Otherwise, the random effects model (the DerSimonian and Laird method) was used. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was assessed by the goodness-of-fit Chi-square test. A sensitivity analysis was mainly performed by omission of a single study each time to assess the stability of obtained pooled ORs. In addition, sensitivity analyses were performed by omission HWE-violating studies. The potential publication bias was estimated by the funnel plot, in which the standard error of log (OR) of each study was plotted against its log (OR). In addition, Funnel plot asymmetry was further assessed by the method of Egger’s linear regression test, in which p<0.05 was considered a significant publication bias. The quality of genotype data was estimated by Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) and low quality studies deviated from HWE were excluded in the sensitivity analysis. All the tests in this meta-analysis were conducted with Comprehensive meta-analysis CMA software (version 2.0; College Station, TX). P-values<0.05 were considered statistically significant. Ethical approval was not necessary, as this was a meta-analysis based on previous studies, and no direct handing of personal data or recruitment of participants.

RESULTS

Study characteristics

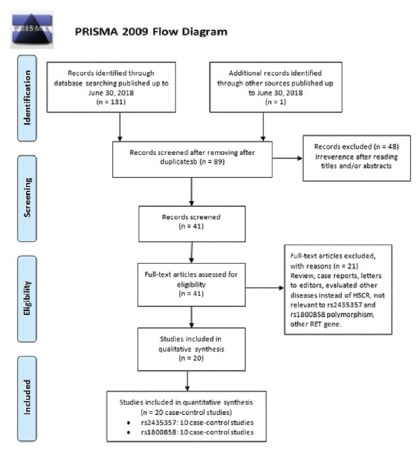

Following the online search of multiple databases, 131 potentially relevant publications were retrieved. As shown in Figure 1, after excluding the duplicates, 89 publications were remained. Among them, 69 publications were excluded because they were irrelevant, reviews/abstracts, not about human subjects, or not published in English. Finally, 20 case-control studies, including nine with 1,136 HSCR cases 2,420 controls for rs2435357 3 , 14 , 19 , 27 , 30 , 32 , 40 , 41 , 42 , and ten with 917 HSCR cases 1,159 controls for rs1800858 5 , 9 , 10 , 12 , 23 , 24 , 30 , 34 , 37 , 39 were included. The characteristics of each study are summarized in Table 1. Among 18 case-control studies, 14 were conducted in Asians and four in Caucasians. All the included studies were published between 2003 and 2017. The HSCR cases sample size ranged from 16 to 362. Genotyping methods used included PCR, PCR-RFLP, TaqMan assay, and PCR-HRM. Fourteen matching for the controls were population-based, two were hospital-based, and two did not stated. All studies showed that the distribution of genotypes in the control group was in agreement with the HWE (p<0.05), except for two studies 22 , 23 for rs2435357 and two 28 , 29 for rs1800858 polymorphisms.

FIGURE 1. Flow chart depicting exclusion/inclusion of individual studies for meta-analysis.

TABLE 1. Main characteristics of studies included in this meta-analysis.

| First Author/Year | Country (Ethnicity) | Genotyping Technique | SOC | Case/Control | Cases | Controls | MAFs | HWE | ||||||||

| Genotypes | Allele | Genotypes | Allele | |||||||||||||

| rs2435357 | TT | TC | CC | T | C | TT | TC | CC | T | C | ||||||

| Zhang 2007 | China (Asian) | PCR | HB | 99/132 | 57 | 28 | 14 | 142 | 56 | 29 | 62 | 41 | 120 | 144 | 0.545 | 0.544 |

| Arnold 2008 | European* | TaqMan | HB | 62/30 | 12 | 27 | 23 | 51 | 70 | 2 | 14 | 14 | 18 | 42 | 0.700 | 0.542 |

| Miao 2010 | China (Asian) | PCR | HB | 315/352 | 228 | 65 | 22 | 521 | 109 | 62 | 169 | 95 | 293 | 359 | 0.550 | 0.390 |

| Phusantisampan 2012 | Thailand (Asian) | PCR-RFLP | HB | 68/120 | 47 | 14 | 7 | 108 | 28 | 31 | 64 | 25 | 126 | 114 | 0.475 | 0.447 |

| Prato 2009 | Italy (Caucasian) | PCR | HB | 22/85 | 11 | 6 | 5 | 28 | 16 | 3 | 32 | 50 | 38 | 132 | 0.776 | 0.435 |

| Zhang 2015 | China (Asian) | TaqMan | NS | 59/59 | 42 | 16 | 1 | 100 | 18 | 13 | 30 | 16 | 56 | 62 | 0.525 | 0.880 |

| 76/59 | 59 | 15 | 2 | 133 | 19 | |||||||||||

| Gunadi 2016 | Indonesia (Asian) | PCR-RFLP | NS | 93/136 | 67 | 22 | 4 | 156 | 30 | 27 | 83 | 26 | 137 | 135 | 0.496 | 0.010 |

| Yang 2017 | China (Asian) | TaqMan | PB | 362/1448 | 209 | 126 | 27 | 544 | 180 | 329 | 802 | 317 | 1460 | 1436 | 0.495 | =0.001 |

| Li 2017 | China (Asian) | TaqMan | NS | 99/114 | 69 | 27 | 3 | 165 | 33 | 19 | 58 | 37 | 96 | 132 | 0.578 | 0.641 |

| rs1800858 | GG | AG | AA | G | A | GG | AG | AA | G | A | ||||||

| Fitze 2003 | German (Caucasian) | NS | HB | 80/120 | 10 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 110 | 65 | 47 | 8 | 177 | 63 | 0.262 | 0.899 |

| Garcia-Barcelo 2005 | China (Asian) | PCR-RFLP | HB | 172/194 | 14 | 40 | 118 | 68 | 276 | 58 | 100 | 36 | 216 | 172 | 0.443 | 0.536 |

| Burzynski 2004 | Netherland (Caucasian) | NS | HB | 105/126 | 21 | 27 | 57 | 69 | 141 | 77 | 40 | 9 | 184 | 58 | 0.230 | 0.242 |

| Zhang 2005 | China (Asian) | PCR | HB | 16/40 | 2 | 1 | 13 | 5 | 27 | 15 | 12 | 13 | 42 | 38 | 0.475 | 0.011 |

| Du 2006 | China (Asian) | PCR | HB | 94/122 | 4 | 33 | 57 | 41 | 147 | 13 | 88 | 21 | 144 | 130 | 0.532 | =0.001 |

| Liu 2008 | China (Asian) | LDR | PB | 116/144 | 11 | 42 | 63 | 64 | 168 | 42 | 73 | 29 | 157 | 131 | 0.454 | 0.789 |

| Saryono 2010 | Indonesia (Asian) | PCR-RFLP | PB | 54/46 | 5 | 23 | 26 | 33 | 75 | 10 | 30 | 6 | 5 | 23 | 0.456 | 0.033 |

| Liu 2010 | China (Asian) | PCR | HB | 125/148 | 12 | 45 | 68 | 69 | 181 | 43 | 75 | 30 | 161 | 135 | 0.456 | 0.794 |

| Tou 2011 | China (Asian) | PCR | HB | 123/168 | 10 | 32 | 81 | 52 | 194 | 52 | 85 | 31 | 10 | 32 | 0.437 | 0.716 |

| Phusantisampan 2012 | Thailand (Asian) | PCR-RFLP | HB | 68/120 | 36 | 23 | 9 | 95 | 41 | 40 | 51 | 29 | 36 | 23 | 0.454 | 0.117 |

* Authors declared that the ancestry of the participants was European (Caucasians); PCR=polymerase chain reaction restriction; PCR-RFLP=polymerase chain reaction restriction fragment length polymorphism; LDR=ligase detection reaction; HB=hospital based; PB= population based; NS=not stated; MAFs=minor allele frequencies; HWE=hardy-weinberg equilibrium.

Quantitative data synthesis

rs2435357

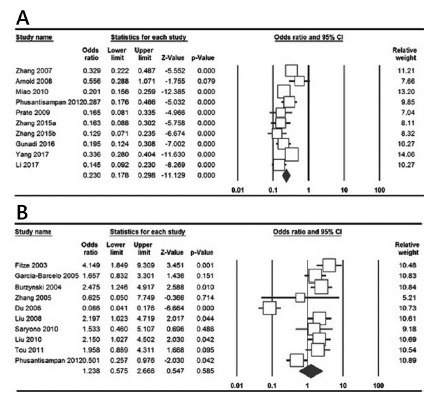

Table 2 listed the main results of the meta-analysis of rs2435357 polymorphism in the RET proto-oncogene and HSCR risk. We pooled all the ten case-control studies to assess the overall association of rs2435357 polymorphism with HSCR risk. Overall pooled analysis suggest a significant association between rs2435357 polymorphism and HSCR risk in overall estimations under all five genetic models, i.e., allele (C vs. T: OR=0.230, 95% CI 0.178-0.298, p=0.001, Figure 2A), homozygote (CC vs. TT: OR=0.079, 95% CI 0.048-0.130, p=0.001); heterozygote (CT vs. TT: OR=0.149, 95% CI 0.048-0.130, p=0.001); dominant (CC+CT vs. TT: OR=0.132, 95% CI 0.098-0.179, p=0.001); and recessive (CC vs. CT+TT: OR=0.239, 95% CI 0.161-0.353, p=0.001).

TABLE 2. Results of the association of RET polymorphism with OA risk.

| Subgroup | Genetic Model | Type of Model | Heterogeneity | Odds Ratio | Publication Bias | |||||

| I2 (%) | PH | OR | 95% CI | Ztest | POR | PBeggs | PEggers | |||

| rs2435357 | ||||||||||

| Overall | C vs. T | Random | 74.18 | =0.001 | 0.230 | 0.178-0.298 | -11.129 | =0.001 | 0.858 | 0.209 |

| CC vs. TT | Random | 60.85 | 0.006 | 0.079 | 0.048-0.130 | -10.008 | =0.001 | 0.371 | 0.178 | |

| CT vs. TT | Random | 58.02 | 0.011 | 0.149 | 0.108-0.205 | -11.670 | =0.001 | 1.000 | 0.156 | |

| CC+CT vs. TT | Random | 59.29 | 0.009 | 0.132 | 0.098-0.179 | -13.220 | =0.001 | 0.371 | 0.068 | |

| CC vs. CT+TT | Random | 52.17 | 0.027 | 0.239 | 0.161-0.353 | -7.184 | =0.001 | 0.107 | 0.219 | |

| rs1800858 | ||||||||||

| Overall | A vs. G | Random | 89.58 | =0.001 | 5.594 | 3.653-8.877 | 7.679 | =0.001 | 0.210 | 0.469 |

| AA vs. GG | Random | 86.57 | =0.001 | 8.453 | 3.783-18.890 | 5.203 | =0.001 | 0.591 | 0.934 | |

| AG vs. GG | Random | 88.56 | =0.001 | 1.238 | 0.575-2.666 | 0.547 | 0.585 | 1.000 | 0.883 | |

| AA+AG vs. GG | Random | 83.71 | =0.001 | 3.469 | 1.881-6.396 | 3.984 | =0.001 | 0.591 | 0.800 | |

| AA vs. AG+GG | Random | 83.23 | =0.001 | 6.120 | 3.608-10.381 | 6.720 | =0.001 | 1.000 | 0.798 | |

FIGURE 2. Forest plots of rs2435357 and rs1800858 polymorphisms in the RET gene and HSCR risk: A) rs2435357 (allele model: C vs. T); B) rs1800858 (heterozygote model: AG vs. GG) .

rs1800858

Table 2 listed the main results of the meta-analysis of rs1800858 polymorphism in the RET proto-oncogene and HSCR risk. Overall pooled analysis suggest a significant association of rs1800858 polymorphism and HSCR risk under four genetic models, i.e., allele (A vs. G: OR=5.594, 95% CI 3.653-8.877, p=0.001); homozygote (AA vs. GG: OR=8.453, 95% CI 3.783-18.890, p=0.001); dominant (AA+AG vs. GG: OR=3.469, 95% CI 1.881-6.396, p=0.001); and recessive (AA vs. AG+GG: OR=6.120, 95% CI 3.608-10.381, p=0.001), but not under heterozygote model (AG vs. GG: OR=1.238, 95% CI 0.575-2.666, p=0.585, Figure 2B).

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis was conducted by omitting each study in each genetic model or removing certain studies such as those studies that did not conform to HWE. After individual study omission, the corresponding pooled OR was not altered significantly. This indicates that our results are statistically robust under all five genetic models examining associations of rs2435357 and rs1800858 polymorphisms with HSCR risk.

Publication bias

Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test were performed to assess the possible publication bias of included studies. The shapes of the Begg’s funnel plot did not reveal any evidence of obvious asymmetry under all five genetic models. In addition, Egger’s linear regression also did not show any significantly statistical evidence of publication bias for rs2435357 under all five genetic models, i.e., allele (C vs. T: PBeggs=0.858 and PEggers=0.209), homozygote (CC vs. TT: PBeggs=0.371 and PEggers=0.178, Figure 3A), heterozygote (CT vs. TT: PBeggs=1.000 and PEggers=0.156), dominant (CC+CT vs. TT: PBeggs=0.371 and PEggers=0.068) and recessive (CC vs. CT+TT: PBeggs=0.107 and PEggers=0.219). Moreover, the Egger’s test did not reveal publication bias rs1800858 polymorphism under all five genetic models, i.e., allele (A vs. G: PBeggs=0.210 and PEggers=0.469), homozygote (AA vs. GG: PBeggs=0.591 and PEggers=0.934), heterozygote (AG vs. GG: PBeggs=1.000 and PEggers=0.883), dominant (AA+AG vs. GG: PBeggs=0.591 and PEggers=0.800) and recessive (AA vs. AG+GG: PBeggs=1.000 and PEggers=0.798, Figure 3B).

FIGURE 3. Funnel plot for the detection of the publication bias for association of rs2435357 and rs1800858 polymorphisms in the RET gene with HSCR risk;a random-effects model was used: A) rs2435357 (homozygote model: CC vs. TT); B) rs1800858 (recessive model: AA vs. AG+GG).

DISCUSSION

The gene for RET proto-oncogene, members of the glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) family, maps to chromosome 10q11.21, contains 21 exons and covers 60kbp DNA36. The RET proto-oncogene encode a trans-membrane receptor tyrosine kinase protein with an extracellular domain rich in cysteine and an intracellular domain enriched in tyrosine that is important in transferring cell growth and differentiation signals33. The RET proto-oncogene germline loss of function mutations are associated with the development of HSCR, while gain of function mutations are responsible for development of various types of human cancer, including medullary thyroid carcinoma, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN 2) and 2B, pheochromocytoma and parathyroid hyperplasia4. To date, several genotype-phenotype correlations have been defined in association of RET mutations with different variants of MEN2 syndrome including MEN 2A, MEN 2B, and familial medullary thyroid carcinoma (FMTC)38.

Several studies have been published exploring the association of the rs2435357 and rs1800858 polymorphisms in RET proto-oncogene with HSCR risk. However, the results of those studies were inconsistent and inconclusive, due to the ethnic differences and small sample size. Therefore, meta-analysis as a powerful tool for summarizing the different studies results is needed to achieve a more comprehensive and reliable conclusion on both polymorphisms in order to provide further insights into this debated subject. This meta-analysis and systematic review, including ten studies with 1,136 cases 2,420 controls for rs2435357 and ten with 917 cases 1,159 controls for rs1800858 were identified and analyzed in this meta-analysis. We found that of rs2435357 and rs1800858 polymorphisms in RET gene are associated with the HSCR risk. These findings are consistent with the meta-analysis by Liang et al 20 . They performed a meta-analysis on association of rs2435357 polymorphism with five studies (566 cases and 719 controls) and rs1800858 polymorphism with nine studies (863 cases and 1,118controls) with HSCR risk. They found rs2435357 and rs1800858 polymorphisms of RET are associated with susceptibility to HSCR. However, their meta-analysis the sample size is rather small and not adequate enough to detect the possible associations.

Between-study heterogeneity is common in meta-analyses, and identifying potential sources of heterogeneity is an essential component of a meta-analysis 26 , 35 . The most potential sources of heterogeneity in a genetic association meta-analysis are study design, ethnicity, genotyping methods, source of controls, and so on 2 , 11 , 29 . Selection bias, although no publication bias was observed, is a possible major source of heterogeneity. Therefore, we have performed subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis by removing HWE-violating studies to found out source of heterogeneity in this meta-analysis. However, heterogeneity before and after the subgroup analysis and process of individual study removing did not reduced or disappeared. Thus, this finding confirmed that the meta-analysis results were statistically robust and that our results were reliable and stable.

This study has two main advantages were as: first, this was the most accurate and comprehensive meta-analysis on rs2435357 and rs1800858 polymorphisms of RET with HSCR risk; second, no publication bias was observed in the present meta-analysis results indicating that our results might be unbiased. However, there were some limitations to this study that may have affected our conclusions. First, the present meta-analysis was limited by relatively small number of studies and sample size on both rs2435357 and rs1800858 polymorphisms, which thus leading to smaller studies in subgroup analysis and weaken statistical power; thus, needs further studies. Second, only studies on Asians and Caucasians populations were involved in this meta-analysis. This bias may exist because we could not determine the role of rs2435357 and rs1800858 polymorphisms in whole populations. Thus, studies on other ethnicities such as Africans and Latinos must be performed to determine the potential effects of ethnic variation on HSCR susceptibility. Third, we have included only the data of published studies, publication bias may be exist, although our results of publication bias tests showed no significance. Fourth, because relevant information was insufficient in the original data, we did not perform stratification analysis by other covariates such as age, gender and so on. This might has caused confounding bias. Finally, it is known that the HSCR has a multifactorial etiology of involving in gene-gene, and gene environment interactions. However, these interactions could not be investigated in the present meta-analysis due to no appropriate data.

CONCLUSION

This meta-analysis suggested that the rs2435357 and rs1800858 polymorphisms in RET proto-oncogene may be associated with susceptibility to HSCR. However, because of the relatively small size of included studies, future large-scale studies on different ethnicity are needed to confirm these findings.

Footnotes

Financial source:none

REFERENCES

- 1.Amiel J, Sproat-Emison E, Garcia-Barcelo M, Lantieri F, Burzynski G, Borrego S. Hirschsprung disease, associated syndromes and genetics a review. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2007;45(1):1–14. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.053959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aslebahar F, Neamatzadeh H, Meibodi B, Karimi-Zarchi M, Tabatabaei RS, Noori-Shadkam M, et al. Association of Tumor Necrosis Factor-a (TNF-a) -308G>A and -238G>A Polymorphisms with Recurrent Pregnancy Loss Risk: A Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Fertility & Sterility. 2019;(4) doi: 10.22074/ijfs.2019.5454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold S, Pelet A, Amiel J, Borrego S, Hofstra R, Tam P. Interaction between a chromosome 10 RET enhancer and chromosome 21 in the Down syndrome-Hirschsprung disease association. Human mutation. 2009;30(5):771–775. doi: 10.1002/humu.20944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borrego S, Wright FA, Fernández RM, Williams N, López-Alonso M, Davuluri R. A Founding Locus within the RET Proto-Oncogene May Account for a Large Proportion of Apparently Sporadic Hirschsprung Disease and a Subset of Cases of Sporadic Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2003;72(1):88–100. doi: 10.1086/345466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burzynski GM, Nolte IM, Osinga J, Ceccherini I, Twigt B, Maas S. Localizing a putative mutation as the major contributor to the development of sporadic Hirschsprung disease to the RET genomic sequence between the promoter region and exon 2. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2004;12(8):604–612. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler Tjaden NE, Trainor PA. The developmental etiology and pathogenesis of Hirschsprung disease. Translational research?: the journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 2013;162(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chumpitazi B, Nurko S. Pediatric gastrointestinal motility disorders challenges and a clinical update. Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2008;4(2):140–148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Pontual L, Pelet A, Trochet D, Jaubert F, Espinosa-Parrilla Y, Munnich A. Mutations of the RET gene in isolated and syndromic Hirschsprung's disease in human disclose major and modifier alleles at a single locus. Journal of medical genetics. 2006;43(5):419–423. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du H, Wang G, Zhang Y, Tao K, Tang S, Niu Y. [Association between RET proto-oncogene polymorphisms and Hirschsprung disease in Chinese Han population of Hubei district] Zhonghuaweichangwaikezazhi = Chinese journal of gastrointestinal surgery. 2006;9(2):152–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitze G, Appelt H, König IR, Görgens H, Stein U, Walther W. Functional haplotypes of the RET proto-oncogene promoter are associated with Hirschsprung disease (HSCR) Human Molecular Genetics. 2003;12(24):3207–3214. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forat-Yazdi M, Jafari M, Kargar S, Abolbaghaei SM, Nasiri R, Farahnak S, et al. Association between SULT1A1 Arg213His (Rs9282861) polymorphism and risk of breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Health Sciences. 2017;17(4) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Barcelo M, Ganster RW, Lui VCH, Leon TYY, So M-T, Lau AMF. TTF-1 and RET promoter SNPs regulation of RET transcription in Hirschsprung's disease. Human Molecular Genetics. 2005;14(2):191–204. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldstein AM, Hofstra RMW, Burns AJ. Building a brain in the gut development of the enteric nervous system. Clinical genetics. 2013;83(4):307–316. doi: 10.1111/cge.12054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gunadi, Dwihantoro A, Iskandar K, Makhmudi A, Rochadi Accuracy of polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism for RET rs2435357 genotyping as Hirschsprung risk. Journal of Surgical Research. 2016;203(1):91–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heuckeroth RO. Hirschsprung disease-integrating basic science and clinical medicine to improve outcomes. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2018;15(3):152–167. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofstra RMW, Elfferich P, Osinga J, Verlind E, Fransen E, LópezPisón J. Hirschsprung disease and L1CAM is the disturbed sex ratio caused by L1CAM mutations? Journal of medical genetics. 2002;39(3):E11. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.3.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamali M, Hantoushzadeh S, Borna S, Neamatzadeh H, Mazaheri M, Noori-Shadkam M. Association between Thrombophilic Genes Polymorphisms and Recurrent Pregnancy Loss Susceptibility in the Iranian Population a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Iranian biomedical journal. 2018;22(2):78–89. doi: 10.22034/ibj.22.2.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krampitz GW, Norton JA. RET gene mutations (genotype and phenotype) of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 and familial medullary thyroid carcinoma. Cancer. 2014;120(13):1920–1931. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Q, Zhang Z, Diao M, Gan L, Cheng W, Xiao P. Cumulative Risk Impact of RET, SEMA3, and NRG1 Polymorphisms Associated With Hirschsprung Disease in Han Chinese. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2017;64(3):385–390. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang C, Ji D, Yuan X, Ren L, Shen J, Zhang H. RET and PHOX2B Genetic Polymorphisms and Hirschsprung's Disease Susceptibility A Meta-Analysis. Leung FCC, editor. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e90091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin Y-C. Nationwide Population-Based Epidemiologic Study of Hirschsprung's Disease in Taiwan. Pediatrics & Neonatology. 2016;57(3):165–166. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lo f Granstro m A, Svenningsson A, Hagel E, Oddsberg J, Nordenskjo ld A, Wester T. Maternal Risk Factors and Perinatal Characteristics for Hirschsprung Disease. PEDIATRICS. 2016;138(1):e20154608–e20154608. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu C, Jin L, Li H, Lou J, Luo C, Zhou X. RET polymorphisms and the risk of Hirschsprung's disease in a Chinese population , Journal of Human. Genetics. 2008;53(9):825–833. doi: 10.1007/s10038-008-0315-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu C-P, Tang Q-Q, Lou J-T, Luo C-F, Zhou X-W, Li D-M. Association Analysis of the RET Proto-Oncogene with Hirschsprung Disease in the Han Chinese Population of Southeastern China. Biochemical Genetics. 2010;48(5-6):496–503. doi: 10.1007/s10528-010-9333-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Machens A, Dralle H. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 achievements and current challenges. Clinics. 2012;67(S1):113–118. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2012(Sup01)19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mashhadiabbas F, Neamatzadeh H, Nasiri R, Foroughi E, Farahnak S, Piroozmand P. Association of vitamin D receptor BsmI, TaqI, FokI, and ApaI polymorphisms with susceptibility of chronic periodontitis A systematic review and meta-analysis based on 38 case-control studies. Dental Research Journal. 2018;15(3):155–155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miao X, Leon TY-Y, Ngan ES-W, So M-T, Yuan Z-W, Lui VC-H. Reduced RET expression in gut tissue of individuals carrying risk alleles of Hirschsprung's disease. Human Molecular Genetics. 2010;19(8):1461–1467. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore SW. The contribution of associated congenital anomalies in understanding Hirschsprung's disease. Pediatric Surgery International. 2006;22(4):305–315. doi: 10.1007/s00383-006-1655-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Namazi A, Forat-Yazdi M, Jafari MA, Foroughi E, Farahnak S, Nasiri R, et al. Association between polymorphisms of ERCC5 gene and susceptibility to gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2017;18(10) doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.10.2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phusantisampan T, Sangkhathat S, Phongdara A, Chiengkriwate P, Patrapinyokul S, Mahasirimongkol S. Association of genetic polymorphisms in the RET-protooncogene and NRG1 with Hirschsprung disease in Thai patients. Journal of human genetics. 2012;57(5):286–293. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2012.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pini Prato A, Rossi V, Mosconi M, Holm C, Lantieri F, Griseri P. A prospective observational study of associated anomalies in Hirschsprung's disease. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2013;8:184–184. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prato AP, Musso M, Ceccherini I, Mattioli G, Giunta C, Ghiggeri GM. Hirschsprung Disease and Congenital Anomalies of the Kidney and Urinary Tract (CAKUT) Medicine. 2009;88(2):83–90. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e31819cf5da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santos MACG dos, Quedas EP de S, Toledo R de A, Lourenço DM, Toledo SP de A. Screening of RET gene mutations in multiple endocrine neoplasia type-2 using conformation sensitive gel electrophoresis (CSGE) Arquivos brasileiros de endocrinologia e metabologia. 2007;51(9):1468–1476. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302007000900009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saryono S, Rochadi R, Lestariana W, Artama WT, Sadewa AH. RET single nucleotide polymorphism in Indonesians with sporadic Hirschsprung's disease. UniversaMedicina. 2016;29(2):71–77. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sobhan MR, Mahdinezhad-Yazdi M, Aghili K, Zare-Shehneh M, Rastegar S, Sadeghizadeh-Yazdi J. Association of TNF-a-308 G?>?A and -238G?>?A polymorphisms with knee osteoarthritis risk: A case-control study and meta-analysis. Journal of Orthopaedics. 2018;15(3):747–753. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2018.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan L, Hu Y, Tao Y, Wang B, Xiao J, Tang Z. Expression and copy number gains of the RET gene in 631 early and mid stage non-small cell lung cancer cases. Thoracic cancer. 2018;9(4):445–451. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tou J, Wang L, Liu L, Wang Y, Zhong R, Duan S. Genetic variants in RET and risk of Hirschsprung's disease in Southeastern Chinese a haplotype-based analysis. BMC Medical Genetics. 2011;12(1):32–32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-12-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang J, Zhang B, Liu W, Zhang Y, Di X, Yang Y. Screening of RET gene mutations in Chinese patients with medullary thyroid carcinoma and their relatives. Familial Cancer. 2016;15(1):99–104. doi: 10.1007/s10689-015-9828-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiansheng Z, Ying Z, Ya G, Quan X, Yitao D, Xinkui G, et al. The relationship between Hirschsprung disease and single nucleotide polymorphisms of c135 in RET proto-oncogene. JOURNAL OF XI'AN JIAOTONG UNIVERSITY (MEDICAL SCIENCES) 2005;26(5):470–472. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang D, Yang J, Li S, Jiang M, Cao G, Yang L. Effects of RET, NRG1 and NRG3 Polymorphisms in a Chinese Population with Hirschsprung Disease. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:43222–43222. doi: 10.1038/srep43222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang X-N, Zhou M-N, Qiu Y-Q, Ding S-P, Qi M, Li J-C. Genetic Analysis of RET, EDNRB, and EDN3 Genes and Three SNPs in MCS + 9 7 in Chinese Patients with Isolated Hirschsprung Disease. Biochemical Genetics. 2007;45(7-8):523–527. doi: 10.1007/s10528-007-9093-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Z, Jiang Q, Li Q, Cheng W, Qiao G, Xiao P. Genotyping analysis of 3 RET polymorphisms demonstrates low somatic mutation rate in Chinese Hirschsprung disease patients. International journal of clinical and experimental pathology. 2015;8(5):5528–5534. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zwink N, Jenetzky E. Maternal drug use and the risk of anorectal malformations systematic review and meta-analysis. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2018;13(1):75–75. doi: 10.1186/s13023-018-0789-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]