Abstract

Background

Many nursing students are not prepared to encounter death and care for patients who are at the end of life as newly educated nurses. The Frommelt Attitude Toward Care of Dying Scale (FATCOD) has been used to assess nursing students’ attitudes during their education and changes have been noted.

Objective

To examine nursing students’ attitudes towards care of dying patients before and after a course in palliative care.

Design

A descriptive study with a pre and post design.

Settings & participants

Nursing students (n = 73) enrolled in a mandatory palliative course in the nursing programme at a Swedish university.

Methods

Data were collected before and after a palliative care course using FATCOD and qualitative open-ended questions. Data from FATCOD were analysed using descriptive and analytical statistics. The open-ended questions were analysed with qualitative content analysis.

Results

The students’ mean scores showed a statistically significant change toward a more positive attitude toward care of dying. Students with the lowest pre-course scores showed the highest mean change. The qualitative analysis showed that the students had gained additional knowledge, deepened understanding, and increased feelings of security through the course.

Conclusions

A course in palliative care could help to change nursing students’ attitudes towards care of patients who are dying and their relatives, in a positive direction. A course in palliative care is suggested to be mandatory in nursing education, and in addition to theoretical lectures include learning activities such as reflection in small groups, simulation training and taking care of the dead body.

Keywords: Nursing, Medicine, Health profession, Education, Attitudes, Work integrated learning, End of life, Nursing education, Nursing students, Palliative care

Nursing; Medicine; Health profession; Education; Attitudes; Work integrated learning; End of life; Nursing education; Nursing students; Palliative care

1. Introduction

From a global perspective, nursing education, including palliative care, varies both in length and content. Many newly graduated nurses are not ready to encounter death and caring for patients at the end of life [1]. Almost all nurses meet and care for patients at the end of life and for many nursing students it will be their first encounter with death. It is thus important to provide education for them due to the complexity of end-of-life care. This study aims to examine nursing students’ attitudes towards care of dying patients before and after a course in palliative care.

2. Background

Caring for patients at the end of life can affect nursing students in different ways and nursing students can feel unprepared for end-of-life care [2]. Their own fears about and reactions to seeing a dead person and anxiety at not be able to support patients and their relatives were major concerns. Students' thoughts about death were found to be more frightening than the actual experience, and taking care of patients until the end of life was experienced as a special situation [3]. Anxiety has been found as a component in other studies too, for example caring for patients who are younger has been shown to provoke anxiety [4]. Nursing students who had experiences with end-of-life care saw death as something more natural to think and talk about, although caring for patients who were dying was still a difficult task they had to deal with [1]. However, death also aroused feelings of helplessness, uncertainty, and inadequacy that could affect students’ attitudes. It has also been shown that nursing students felt unprepared to deal with end-of-life care [2]. It can be challenging to deal with own feelings and at the same time provide caring when caring for patients in end of life [5].

There are several questionnaires to measure attitudes concerning death and palliative care for undergraduate students within health care [6]. The Frommelt Attitude Toward Care of Dying Scale (FATCOD) [7] is one such way to measure attitudes about end-of-life care. FATCOD is translated, tested and validated into Swedish [8], and the questionnaire has also been used in several countries within varying cultures and contexts such as Iran, Japan, Palestine, Sweden, Turkey and USA [8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13]. To enable comparisons with other Swedish studies [1, 14, 15] we chose FATCOD.

2.1. Research utilizing FATCOD score

The questionnaire has been used for both graduated nurses and nursing students. Relationships among demographic variables and nurses' attitudes towards death and caring for dying patients showed that nurses saw death as a natural part of life and as a relief from pain and suffering [10]. According to FATCOD, nurses found it difficult to manage in-home care for older patients with cancer [9]. For nursing students, the FATCOD mean score was significantly higher for students who wanted to provide care for dying patients than for those who did not [11]. Differences in attitudes between nursing students from different countries have also been reported. Iranian students seemed to have more fear of death than Swedish students, who also were more likely to interact and talk with dying persons [12]. Nevertheless, both groups were of the opinion that professional and personal competence was important in palliative care. Attitudes about end-of-life care have also been shown to be different for students from the same province depending on individuals’ experiences with death: students with more experiences with death had less positive attitudes toward caring than students with less experiences with death [16].

Studies have also investigated the effect of both shorter and longer education on attitudes toward care of dying persons. According to FATCOD scores, a one-day workshop, engaging nursing students' in scenarios with end-of-life care situations changed their attitudes and feelings concerning end-of-life care towards more positive attitudes. Students who had received education on death and dying had scores higher than students who had not received such education. A six-week educational component in palliative care improved nursing students' attitudes towards end-of-life care compared to students who did not receive this education [17]. A Swedish longitudinal study including six universities found changes in attitudes over the whole nursing education (comprising theoretical education on palliative care to various extents) in favour of a more positive attitude [14]. Nurses who participated in a post-graduate program in palliative care nursing showed a change in their attitudes regarding understanding patients' attitudes about their pain, suffering, treatment, and care [18]. Despite nursing students’ positive attitudes as measured by FATCOD, over one-third expressed that they needed more education in palliative care [19].

For nursing students, death and dying can provoke anxiety that can affect their attitudes towards end-of-life care. Some studies have examined nursing students' attitudes about end-of-life care using FATCOD, although few studies have examined changes in students' attitudes due to education. This study examines nursing students’ attitudes towards care of dying patients before and after a course in palliative care.

3. Methods

3.1. Design

This descriptive study has a pre and post design that combines data from a questionnaire and data from qualitative open-ended questions.

3.2. Setting and context

In Sweden, nursing education is a three-year Bachelor's degree programme [20]. The education has a national course outline setting the outer borders but giving each university opportunities to shape the education in different ways, within limits. This means that specific subjects such as palliative care are given varying degrees of attention at different universities. The present study was performed at a university in Western Sweden providing a dedicated five-week course in palliative care offering 7.5 HE credits, Palliative Care (PC), during the students' last semester out of six. The students had a basic theoretical introduction to the concept of palliative care during their first year of education. They might also have met patients in the late phase of life during their clinical practice in the second and fourth semester. The course focuses on the late phase of end of life based on World Health Organization's (WHO) definition of palliative care [21]. The following topics are covered in the 12 lectures of the course: the most common palliative diagnoses, relief from distressing symptoms, ethical issues, care of relatives including children as relatives, physical and mental changes in the dying patient, and the importance of advocating for the patient and their relatives. The students were encouraged to keep a diary to reflect on palliative care and to support processing of the course content.

The course has three examining seminars, including one practical examination at the clinical training centre and one final home examination examining the course goals. All seminars take place in smaller groups to allow for the students to take active part in discussion and reflection. The first seminar utilizes a standardized patient case from the National Council for Palliative Care in Sweden and links it to the rights of the dying person [22]. The second seminar is about common palliative medical diagnoses and diagnosis-specific symptoms at the end of life, aiming to give the students a holistic understanding of challenges in palliative care. The third seminar, performed at the clinical training centre, is conducted as a simulation where the students take care of a dying person and relatives at the moment of death, and care for the dead body. This examination also tests the students’ knowledge about legal regulations concerning actions in connection with death and criteria for determining death in Sweden. The course was taught by lecturers and senior lecturers with theoretical education in palliative care as well as long clinical experience from work in various palliative care contexts. Lectures were also given for example, by professionals clinically active in the context of palliative care in a broader sense, such as a registered nurse from hospice, a religious representative (minister) and a mortician.

3.3. Participants and data collection

All nursing students (n = 80) from the mandatory Palliative care course in the nursing programme in autumn 2016 were invited to participate. The pre-course questionnaire was distributed to the students at the course introduction by the last author (ÅR), and the post-course questionnaire was distributed at the end of the course by the first and second authors (MK and IB). All students (n = 80) were present at the course introduction and chose to fill out the pre-course questionnaire. Not all students participated at the end of the course and seven students (two male and five females) did not fill out the post-course questionnaire. The questionnaires for all students answering both the pre- and the post-course questionnaires were included in the study (n = 73).

3.4. The pre- and post-course questionnaires

The Swedish version of the FATCOD [8], based on Frommelt's original version [7], was used to measure nursing students' attitudes about end-of-life care before and after the course in palliative care (Box 1). The pre-course questionnaire also had questions about demography (Table 1), birth country (Table 2), religious beliefs, experience of care of dying persons (private or professional), and one open-ended question about the students' views about death. “What is your view about death?” The post-course questionnaire had, in addition to the FATCOD, also two questions addressing whether the course had meant any change to the students; “My preconceptions about death have changed after the course” (Likert type) and the open-ended question “Has participating in this course meant a change to you concerning palliative care?”.

Box 1. Description of the questionnaire FATCOD – Frommelt Attitude Towards Care of Dying Scale.

| FATCOD – Frommelt Attitude Towards care of Dying Scale | |

|---|---|

| Construction | FATCOD has 30 items to measure attitudes towards death and caring measured on a five-point Likert scale – 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree) – min 30 and max 150 score [7]. |

| Domains | The original FATCOD was a single domain scale [7], but was later found to consist of two domains [23]. The two domains are Positive attitude toward caring for the dying patient, FATCOD I, with the items 1–3, 5–11, 13–15, 17, 26, 29, and 30 Perception of patient- and family-centred care, FATCOD II, with the remaining items. |

| Validity and reliability | The original FATCOD has been assessed regarding content validity (content validity index) and test-retest reliability (Pearson product-moment correlation = .94 and .90) [7]. |

| Validation of the Swedish version | The Cronbach's alpha in the Swedish version of FATCOD was .51 and increased to .60 when item 25 was omitted. If items 1, 2, 10, 23, 25, and 30 were deleted, the Cronbach's alpha increased to .70. The validation of the Swedish version [8] confirmed the two domains – FATCOD I and FATCOD II – found in the Japanese version [23]. However, the Cronbach's alpha was low for the two domains in the Swedish version [8]. |

| Critique of the questionnaire | The scale has been shown to measure a two-dimensional construct [8, 24]. It has been found to contain items that could be revised or omitted, and items 10 and 25 in particular are said to be problematic [24]. |

Alt-text: Box 1

Table 1.

Age shown in total and divided by gender.

| Age, mean years | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| All (n = 73) | 27.6 | 21–59 |

| Female (n = 67) | 27.8 | 21–59 |

| Male (n = 6) | 25.8 | 23–29 |

Table 2.

The students’ birth country.

| Country | N |

|---|---|

| Sweden | 66 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 2 |

| Brazil | 1 |

| Colombia | 1 |

| Kosovo | 1 |

| Poland | 1 |

| Russia | 1 |

3.5. Analysis

Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 23. No items were omitted for the analysis. Items 1, 2, 4, 6, 10, 12, 16, 18, 20–24, 27, and 30 were considered to be positively worded statements. We consider all other items negative and consequently reversed them for the analysis. The scores were analysed according to demographical data, since these variables have previously been shown to be important [1, 11, 12].

The statistical significance was established at a 5% significance level and a 95% confidence interval. Descriptive statistics – i.e., frequencies, means, ranges, and standard deviations for the FATCOD scores – were calculated based on a normal distribution. FATCOD scores and ages were divided into age groups based on quartiles (Q): Q 1 = 21–23 years, Q 2 = 23–25 years, Q 3 = 25–28 years, and Q 4 = 28–59 years. FATCOD scores were also analysed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Effect size index (r) was established at .10 for small effect, .30 for medium effect, and .50 for large effect [25].

The questionnaires' internal consistency validation for each subscale was assessed. A Cronbach's alpha value of α > 0.7 was considered to be satisfactory [26]. FATCOD scores and ages were analysed using Pearson's correlation test.

The open-ended questions were analysed with content analysis based on Krippendorff's description [27]. The content for each question was first compiled based on differences and similarities and summarized based on meanings by the last author (ÅR), and after that discussed and revised in the research group.

3.6. Ethical considerations

The head of the department for the nursing education approved the study. In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [28], the participants were verbally informed about the study, the voluntariness of participating and the possibility to withdraw at any time without negative consequences. We made no attempt to persuade the students to fill out the forms and neither did we ask students who did not fill out the forms about their reasons for that. Due to the sensitive nature of the questions asked in this study, the participants were assured confidentiality. The subject could create strong emotions and we were prepared to handle this through the lecturer responsible for the course, who was not part of the research group. The lecturer has long experience of handling existential and other end-of-life related questions from her clinical practice within palliative care.

4. Results

4.1. Change in FATCOD scores

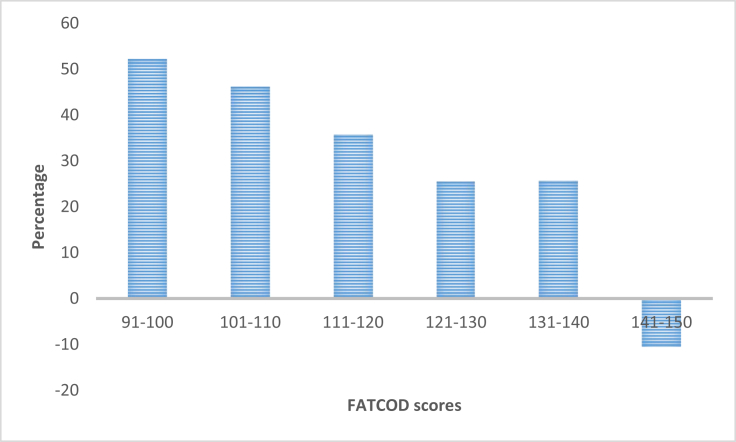

From pre-course to post-course, the nursing students' (n = 73) overall FATCOD mean score changed by 9.6 points in favour of a more positive attitude (Table 3). The change was statistically significant, with a large effect size. The Cronbach's alpha was 0.741 pre-course and 0.715 post-course. The change in students' mean scores for the FATCOD I and II domains were also statistically significant, with a medium effect size. The Cronbach's alpha for the FATCOD I domain was 0.76 pre-course and 0.70 post-course and for FATCOD domain II 0.44 pre-course and 0.50 post-course. Both male (n = 6) and female (n = 67) students changed their attitudes in a more positive direction from pre-course to post-course and the change was statistically significant with effect size changing from medium to large (Table 3). The difference in mean score between male and female students' pre-course was statistically significant, with a medium effect size. The male students' mean FATCOD post-course score was significantly lower than the female students' mean post-course, with a low effect size. The students' change in FATCOD score ranged from –6 to +36. Five out of 73 students had changed their total score in a negative direction post-course compared to pre-course, and three showed no change in total scores. Students with the lowest pre course scores had the highest change both in absolute numbers (+36 points) and as mean percentage change (+52.2 %) of the possible change in FATCOD scores (Fig. 1). Students with negative change in FATCOD scores were in the three groups with the highest FATCOD scores.

Table 3.

FATCOD score comparison between sex pre- and post-PC course shown as a total and for each domain.

| Participants (n = 73); male = 6, female = 67 | Pre-PC course Mean (SD) |

Post-PC course Mean (SD) |

Significance | Effect size (r) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FATCOD | All | 123.0 (10.1) | 132.6 (9.1) | p < .001 | r = .94 |

| Male | 115.4 (8.3) | 124.8 (9.5) | p = .028 | r = -.47 | |

| Female | 123.7 (10,0) | 132.6 (7.4) | p < .001 | r = -.56 | |

| Male | 115.4 (8.3) | ||||

| Female | 123.7 (10,0) | p = .001 | r = -.41 | ||

| Male | 124.8 (9.5) | ||||

| Female | 132.6 (7.4) | p = .001 | r = -.22 | ||

| FATCOD I | All | 61.4 (8.2) | 66.4 (6.1) | p < .001 | r = -.49 |

| Male | 58.0 (7.4) | 60.8 (6.8) | p = .343 | r = -.19 | |

| Female | 61.7 (8.3) | 66.9 (5.8) | p < .001 | r = -.72 | |

| Male | 58.0 (7.4) | ||||

| Female | 61.7 (8.3) | p < .001 | r = -.23 | ||

| Male | 60.8 (6.8) | ||||

| Female | 66.9 (5.8) | p < .001 | r = -.43 | ||

| FATCOD II | All | 61.4 (8.2) | 66.4 (6.1) | p < .001 | r = -.49 |

| Male | 58.0 (7.4) | 60.8 (6.8) | p = .343 | r = -.19 | |

| Female | 61.7 (8.3) | 66.9 (5.8) | p < .001 | r = -.72 | |

| Male | 58.0 (7.4) | ||||

| Female | 61.7 (8.3) | p < .001 | r = -.23 | ||

| Male | 60.8 (6.8) | ||||

| Female | 66.9 (5.8) | p < .001 | r = -.43 |

Fig. 1.

Nursing students' mean percentage change of the possible change in FATCOD scores from pre course to post course.

4.1.1. Change in FATCOD scores related to age, birth country, and religious beliefs

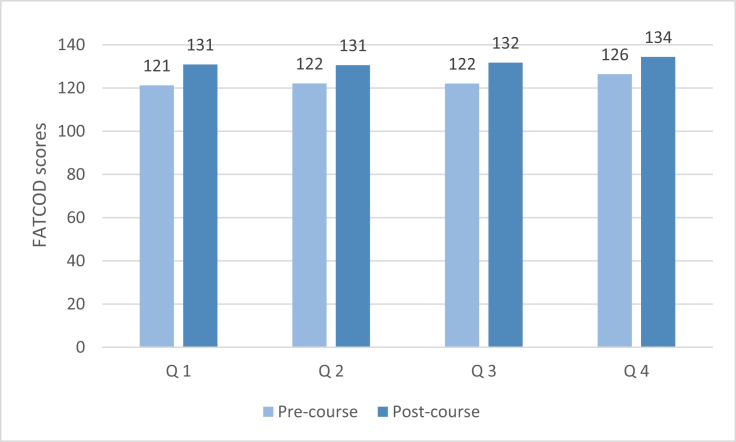

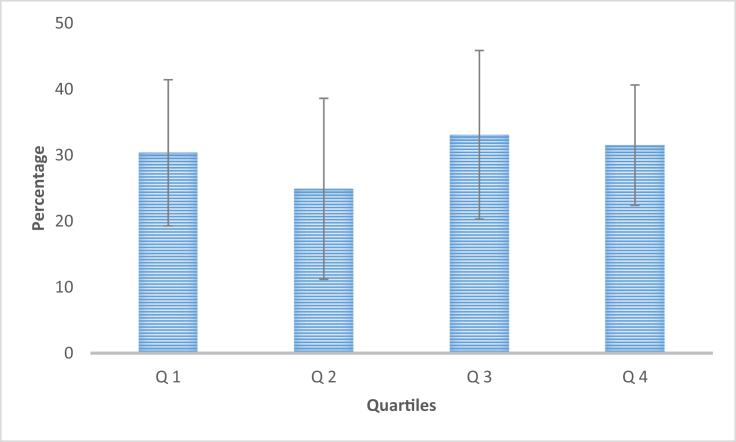

The age group Q 4 (28–59 years) had slightly more positive attitudes both pre- and post-course albeit the difference is small in absolute numbers (Fig. 2). When examining the mean change of the possible change in FATCOD scores, no difference between the quartiles can be seen; that is, we found no correlation for change in FATCOD scores with the students’ age (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Students FATCOD scores shown as pre and post course scores divided by quartile age groups: Q 1 = 21–23 years; Q 2 = 23–25 years; Q 3 = 25–28 years; Q 4 = 28–59 years.

Fig. 3.

Nursing students mean percentage change of the possible change of FATCOD scores divided by quartile age groups: Q 1 = 21–23 years; Q 2 = 23–25 years; Q 3 = 25–28 years; Q 4 = 28–59 years.

There were no significant differences in FATCOD mean scores between nursing students born in Sweden and those students born in other countries or those with experience of caring for dying persons compared to those with no such experience. That is, we found no difference in FATCOD scores either pre-course or post-course. There were also no significant differences in the FATCOD mean score between religious participants (22%) and non-religious participants.

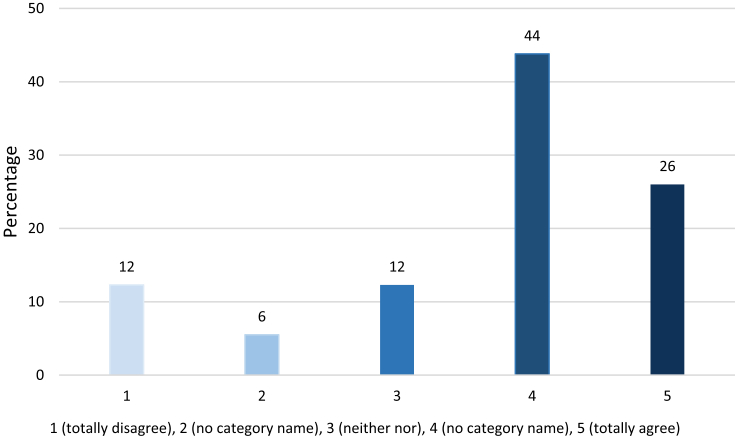

The open-ended question in the pre-course questionnaire “What is your view about death?” was answered by 63 (86%) students. Most answers reflected the nursing perspective and not a personal view. Death was viewed as a natural part of life and as a unique experience for every person. Death was described as being both precious and a relief, as well as something that could be frightening and unjustified. It was also described as accompanied by both pain and other symptoms, and that it could involve suffering. Death was seen as a difficult situation with many challenges for the nurse, where contact with relatives and easing symptoms were mentioned. The question “Has participating in this course meant any change to you concerning palliative care?” in the post-course questionnaire was answered by 43 (59%) students. The analysis showed that the majority of the students believed that they had gained additional knowledge, a new awareness, a deeper understanding, and an increased feeling of security through the course. Some students stated that the course had not contributed to their view of caring for dying patients and that the course had made them view palliative care as being more complex and difficult. The answers showed that 70% of the students had answered that the course had changed their preconceptions about death (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Nursing students' opinions of whether the course had meant any change in preconceptions about death from totally disagree to totally agree.

5. Discussion

5.1. Strengths and limitations

Although our sample is limited in size, > 90 % of the students in the course participated. The results furthermore show statistically significant changes in attitudes after the palliative course and the material is thus large enough. The distribution between male and female students is uneven, although the distribution reflects the reality of the gender distribution in the nursing education. Nonetheless, this skewness and the reality of the gender distribution limit the possibility to draw conclusions about differences based on gender. Nor can conclusions based on age be made due to the small sample, but a trend of more positive attitudes pre-course among older students could be seen. The students also scored fairly high (mean 123) pre-course, and this limits the possibility for attitudes to change in a positive direction. Does this reflect the breakthrough of palliative care in contemporary care in Sweden today? If so, it is gratifying for the palliative care concept. We saw that five students among those with the highest scores pre-course changed their attitudes in a negative direction post-course. This might be a result of chance, since the changes for these students were close to the maximum, or this might be attributed to the ceiling effect of the questionnaire. It might also reflect a real change in attitude since some students in the open-ended question stated that after the course they understood the complexities in palliative care in a new way.

The answers to the open-ended questions were mostly short (a few words or sentences), and thereby only allowed for basic compilation. For the question about the student's own views about death, the answers mostly took the nursing perspective as a starting point, not the students' personal views. One can wonder whether this is an attempt by the students to distance themselves from such a personal question or if it is the nursing students' attempt to act as nurses?

The FATCOD measure has been revised since the first version [29] and has also been translated into many languages. It is constructed with both positively and negatively worded items and some answers should accordingly be reversed before the analysis, giving the highest scores for the most positive attitudes. Because the original article [7] does not state which answers should be reversed, some uncertainties exist. That is, which items that are reversed differ between different FATCOD versions. This might be according to cultural and organisational differences. These items include items whether it is the nurse's responsibility to talk about death with patients (item 6) and whether dependency on pain medication at the end of life is seen as a problem (item 25). We have used the Swedish version of FATCOD; however, unlike Henoch, Browall et al. [8], we did not reverse item 6 and we did reverse item 25, due to what we consider to be in line with what is viewed as a positive attitude in the palliative care concept in Sweden. These issues create difficulties when trying to interpret and compare results between studies utilizing the FATCOD measure. Some degree of caution is thus advised.

It also has been argued that the FATCOD scale [24] has issues in terms of validity (Box 1) and the low Cronbach's alpha in the present study points to this problem. We have not studied the long-term effects of the education on palliative care, which limits the possibilities for drawing conclusions on the effect for nurses' working life and thus the quality of care for patients at the end of life.

5.2. Discussion of the results

The nursing students in this study took a dedicated five-week course in palliative care in the last semester of their three-year education. Our study clearly shows a statistically significant positive change in attitude after the course. This result is in line with Mallory's findings [17] and with findings that attitudes correlated with the extent of theoretical education in palliative care [14]. Moreover, these results were seen despite the already high pre-course FATCOD scores. The largest change in attitude was +36 in favour of a more positive attitude, but changes towards a more negative attitude, albeit to a lesser extent with –6 scores, also occurred. Those with the greatest change in attitudes in a positive direction were shown to be those with the least positive attitude pre-course. When considering the aim of the course in palliative care (i.e., to promote qualitatively good care at end of life and positive attitudes towards caring for dying patients), this can be seen as a favourable outcome. Those holding the most negative attitudes pre-course also seemed to gain the most from taking the course. However, we must bear in mind that what is captured by a questionnaire about attitudes is always a little unclear. In this study, we captured a difference between the two measures, which seems likely to represent a real change in attitude independent of the questionnaire per se.

The FATCOD mean post-course score in the present study is similar to what has been previously reported from a Swedish context: 133 vs. 132 [14]. This similarity indicates that the change in the students' attitudes towards care of dying persons in a more positive direction is likely to take place if they receive education and training on palliative care. Due to that study's longitudinal design [14], there was a substantial drop-out, limiting the possibilities for making comparisons with the present study. Several factors contributing positively to attitudes, such as being born in Sweden, being older (>35 years), and having experience of meeting a dying person have also been found previously [15]. In the present study, we could not replicate this. We found that the oldest students had slightly higher FATCOD scores both before and after the course, but it was not a contributing factor. However, it is possible that persons with longer life experience have a more positive attitude towards death in general and towards care of dying in particular, reflecting the difference seen in this study according to age. The other two factors, being born in Sweden and having experience of meeting with dying persons, were neither contributing factors in present study.

In the validation of the Swedish version of FATCOD [8], it was found that students' encounters with dying patients were not predictors for attitudes towards caring for dying patients, whereas gender was found to be a contributing factor although not a predictor. In the present study, neither of these differences were found. The number of men in the present study was however too small to allow for a conclusion based on gender. The majority of the students in the present study were born in Sweden and almost all of the students had experience with meeting a dying person compared to about one-third in the study by Lundh Hagelin, Melin-Johansson et al. [15]. The latter might be explained by the fact that the students in the present study took the palliative care course during their sixth semester, so they may have met a dying person during their education. Therefore, this limits our possibilities to analyse the impact of this factor. We did not find that the FATCOD scores were affected by religious beliefs as has been reported in a previous study [11]. This finding might be due to the fact that Sweden is a highly secularized country, the fifth least religious country globally [30]. The answers to the question about the students' conceptions about death and changes related to the course do not give the direction of the change. However, the change in FATCOD scores indicates that the change in conceptions about death has an impact on their attitude toward caring for dying patients. Most students’ answers to this question conformed to the changes in their FATCOD scores post-course.

Strang, Bergh et al. [1] showed that second year nursing students felt unprepared to care for patients at the end of life. At this point in their three-year education, the students had not received any theoretical education in palliative care. Nursing students have reported feeling unprepared to take care of a dead body and meet relatives despite having taken a course in palliative care [14]. The palliative course in the present study contains practical training on both these issues and might thus contribute to the positive change in FATCOD scores from pre-course to post-course. It is important for nursing education in palliative care to combine theoretical knowledge with realistic end-of-life care scenarios [31]. This approach can prepare them for challenges they may face as nurses in end-of-life care. It has also been argued that nursing students need to discuss and reflect on end-of-life care to be confident in their profession [3]. The students in present study were given such an opportunity through the course in palliative care. Frommelt [7] stated that the only factor that significantly contributed to educated nurses' attitudes toward care of dying was having taken a course within the field. Our study shows a clear shift towards more positive attitudes after having taken such a course, suggesting that Frommelt's findings also apply to nursing students. The impact of a palliative course seems to be of value for promoting positive attitudes towards caring for dying patients, independent of the students' demographics and previous experience of caring for dying persons.

6. Conclusion

The study clearly shows a positive change in attitudes for nursing students after taking a five-week course in palliative care in the last semester of their nursing education. Education in palliative care seems to improve nursing students’ attitudes towards care of dying persons. This is important since all nurses working in health care might encounter end-of-life care and have to care for dying patients and their relatives.

Through a course in palliative care, nursing students are better prepared to handle encounters with patients and their relatives at end of life in their work as graduated nurses, ensuring a better care for the patients and their relatives. We accordingly conclude that a dedicated course, of a sufficient extent, in palliative care should be a mandatory part of nursing education. The results of this study propose that, in addition to theoretical education, a course in palliative care should include learning activities involving reflection. Simulation training that takes care of a dying person, the next of kin, and the dead body at the clinical training centre as part of a work-integrated learning pedagogy also seems to be of value in preparing nursing students for work in palliative care as graduate nurses. The results suggest that knowledge about palliative care, reflection, and practical training including simulation helps nursing students change their attitudes. Through this their encounters with patients and relatives at the end of life as graduated nurses might not be so frightening and foreign.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Ina Berndtsson, Åsa Rejnö: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Margareta Karlsson: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participating nursing students as well as the lecturer responsible for the palliative course, Birgitta Stenström. Thanks also to Per Nordin for guidance with the statistical analysis. We are grateful for the support from the Department of Health Sciences, University West, Sweden.

References

- 1.Strang S., Bergh I., Ek K., Hammarlund K., Westin L., Prahl C. Swedish nursing students' reasoning about emotionally demanding issues in caring for dying patients. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2014;20(4):194–200. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2014.20.4.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gillan P.C., van der Riet P.J., Jeong S. End of life care education, past and present: a review of the literature. Nurse Educ. Today. 2014;34(3):331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ek K., Westin L., Prahl C., Österlind J., Strang S., Bergh I. Death and caring for dying patients: exploring first-year nursing students' descriptive experiences. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2014;20(10):509–515. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2014.20.10.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper J., Barnett M. Aspects of caring for dying patients which cause anxiety to first year student nurses. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2005;11(8):423–430. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2005.11.8.19611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karlsson M., Berggren I., Kasén A., Wärnå-Furu C., Söderlund M. A qualitative metasynthesis from nurses' perspective when dealing with ethical dilemmas and ethical problems in end-of-life care. Int. J. Hum. Caring. 2015;19(1):40–48. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frey R.A., Gott M., Neil H. Instruments used to measure the effectiveness of palliative care education initiatives at the undergraduate level: a critical literature review. BMJ Supp.; Palliative Care. 2013;3(1):114. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frommelt K.H. The effects of death education on nurses' attitudes toward caring for terminally ill persons and their families. Am. J. Hosp. Pall. Care. 1991;8(5):37–43. doi: 10.1177/104990919100800509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henoch I., Browall M., Melin-Johansson C., Danielson E., Udo C., Johansson Sundler A. The Swedish Version of the Frommelt Attitude toward Care of the Dying Scale: aspects of validity and factors influencing nurses’ and nursing students’ attitudes. Cancer Nurs. 2014;37(1):E1–E11. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e318279106b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsui M., Kanai E., Kitagawa A., Hattori K. Care managers' views on death and caring for older cancer patients in Japan. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2013;19(12):606–611. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2013.19.12.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunn K.S., Otten C., Stephens E. Nursing experience and the care of dying patients. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2005;32(1):97–104. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.97-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arslan D., Akca N.K., Simsek N., Zorba P. Student nurses' attitudes toward dying patients in central Anatolia. Int. J. Nurs. Knowl. 2014;25(3):183–188. doi: 10.1111/2047-3095.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iranmanesh S., Axelsson K., Häggström T., Sävenstedt S. Caring for dying people: attitudes among Iranian and Swedish nursing students. Indian J. Palliat. Care. 2010;16(3):147–153. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.73643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abu-El-Noor N.I., Abu-El-Noor M.K. Attitude of Palestinian nursing students toward caring for dying patients: a call for change in health education policy. J. Holist. Nurs. 2016;34(2):193–199. doi: 10.1177/0898010115596492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henoch I., Melin-Johansson C., Bergh I., Strang S., Ek K., Hammarlund K. Undergraduate nursing students’ attitudes and preparedness toward caring for dying persons – a longitudinal study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2017;26:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lundh Hagelin C., Melin-Johansson C., Henoch I., Bergh I., Ek K., Hammarlund K. Factors influencing attitude toward care of dying patients in first-year nursing students. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2016;22(1):28–36. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2016.22.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iranmanesh S., Sävenstedt S., Abbaszadeh A. Student nurses' attitudes towards death and dying in south-east Iran. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2008;14(5):214–219. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2008.14.5.29488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mallory J.L. The impact of a palliative care educational component on attitudes toward care of the dying in undergraduate nursing students. J. Prof. Nurs. 2003;19:305–312. doi: 10.1016/s8755-7223(03)00094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rønsen A., Hanssen I. Communication in palliative care: philosophy, teaching approaches, and evaluation of an educational program for nurses. Nurse Educ. Today. 2009;29(7):791–795. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grubb C., Arthur A. Student nurses’ experience of and attitudes towards care of the dying: a cross-sectional study. Palliat. Med. 2016;30(1):83–88. doi: 10.1177/0269216315616762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higher Education Ordinance. vol. 1096. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.WHO . World Health Organization; 2002. Definition of Palliative Care: WHO.http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en [cited 2019 18 July]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barbus A.J. The dying person's bill of rights. Am. J. Nurs. 1975;75(1):99. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyashita M., Nakai Y., Sasahara T., Koyama Y., Shimizu Y., Tsukamoto N. Nursing autonomy plays an important role in nurses' attitudes toward caring for dying patients. Am. J. Hosp. Pall. Care. 2007;24(3):202–210. doi: 10.1177/1049909106298396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leombruni P., Loera B., Miniotti M., Zizzi F., Castelli L., Torta R. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Frommelt attitude toward care of the dying scale (FATCOD-B) among Italian medical students. Palliat. Support. Care. 2015;13(5):1391–1398. doi: 10.1017/S1478951515000139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992;112(1):155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Connelly L.M. Research Roundtable. Cronbach's alpha. Medsurg Nurs. 2011;20(1):45. 4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krippendorff K. third ed. SAGE; Thousand Oaks, California: 2013. Content Analysis : an Introduction to its Methodology; p. 441. [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2013;310(20):2191–2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frommelt K.H. Attitudes toward care of the terminally ill: an educational intervention. Am. J. Hosp. Pall. Care. 2003;20(1):13–22. doi: 10.1177/104990910302000108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gallup International . 2017. Religion Prevails in the World: Gallup International.http://www.gallup-international.bg/en/36009/religion-prevails-in-the-world/ [cited 2019 18 July]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brajtman S., Higuchi K., Murray M.A. Developing meaningful learning experiences in palliative care nursing education. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2009;15(7):327–331. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2009.15.7.43422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]