Abstract

Aortic aneurysms represent a significant clinical problem as they largely go undetected until a rupture occurs. Currently, an understanding of mechanisms leading to aneurysm formation is limited. Numerous studies clearly indicate that vascular smooth muscle cells play a major role in the development and response of the vasculature to hemodynamic changes and defects in these responses can lead to aneurysm formation. The LDL receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) is major smooth muscle cell receptor that has the capacity to mediate the endocytosis of numerous ligands and to initiate and regulate signaling pathways. Genetic evidence in humans and mouse models reveal a critical role for LRP1 in maintaining the integrity of the vasculature. Understanding the mechanisms by which this is accomplished represents an important area of research, and likely involves LRP1’s ability to regulate levels of proteases known to degrade the extracellular matrix as well as its ability to modulate signaling events.

Keywords: Lipoprotein receptors, LRP1, proteases, aneurysms, smooth muscle cells, extracellular matrix

1. INTRODUCTION

Aortic aneurysms result from the progressive enlargement of the aorta and render the vessel wall unstable, prone to life-threatening dissections and ruptures. This disease was the primary cause of 9,863 deaths in the United States in 2015 [1]. Currently, the two major treatments for aortic aneurysms include drugs to lower the hemodynamic stress on the vessel wall and surgery to replace the injured section of the vessel. However, most aortic aneurysms go undetected until they rupture. Unfortunately, our current understanding of the molecular mechanisms leading to aneurysm formation is limited.

It is becoming clear that vascular smooth muscle cells (SMC) play a major role in both the appropriate development and maintenance of the vasculature. Exactly how SMC function to maintain the vasculature and their response to injury is an active area of investigation. SMC are responsible for the production, mechanosensing and mechanoregulation of the extracellular matrix [2]. The major extracellular matrix components in large elastic arteries are elastin and collagen [3]. Elastin provides reversible extensibility during the cardiac cycle, while collagen provides strength and prevents failure at high pressure [3]. Elastin does not turn over in normal, healthy arteries [4], thus damage or degradation of elastin results in severe consequences, including aortic dissections and aneurysms. The direct connection between vascular SMC and elastin fibers is provided by the “elastin-contractile unit” (reviewed in [5]) in which the elastic fibers of the aortic medial wall are surrounded by microfibrils which are attached to the dense plaques and focal adhesions in SMC. Failure of appropriate mechanosensing of SMC, defined as the communication of SMC with the surrounding extracellular matrix, can lead to aortic aneurysms and dissections [2]. Recent investigations have identified the LDL receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) as a major SMC receptor that functions to maintain the integrity of the vasculature [6–9].

Originally identified as the hepatic receptor responsible for the catabolism of α2M-protease complexes [10, 11], LRP1 is now known to bind and mediate the internalization of numerous ligands and to also function in signaling pathways [12, 13]. Deletion of the Lrp1 gene in mice results in early embryonic lethality at E13.5 [14, 15] due to extensive hemorrhaging resulting from a failure to recruit and maintain SMC and pericytes in the vasculature. Genetic studies have revealed that selective deletion of LRP1 in neurons [16], macrophages [17–21], hepatocytes [22, 23], SMC [6–9], or endothelial cells [24, 25] all lead to significant phenotypic alterations revealing critical roles for LRP1 in regulating physiological processes. For example, selective deletion of LRP1 in SMC has revealed that LRP1 protects against the development of atherosclerosis by controlling platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor activation and prevents aneurysm formation by mechanisms that are not currently well defined. This review will briefly summarize the features of LRP1 and then discuss its role in regulating the integrity of the vasculature.

2. LRP1 IS A MEMBER OF A HIGHLY CONSERVED RECEPTOR FAMILY

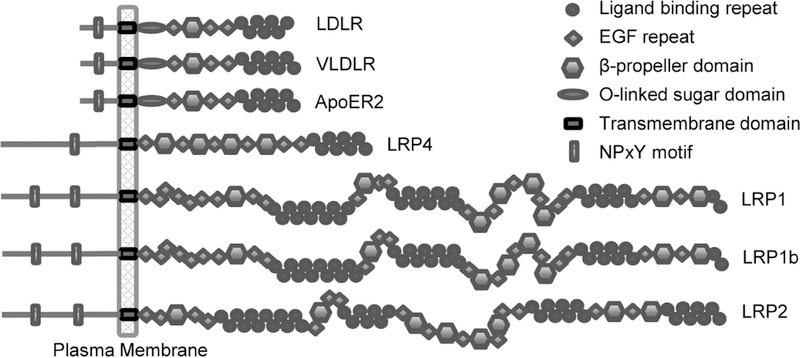

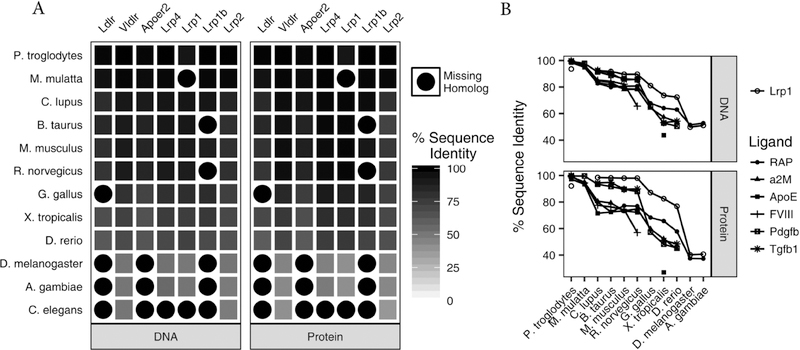

LRP1 is a member of the LDL receptor family which includes the LDL receptor, the VLDL receptor, apoE receptor 2, LRP4, LRP1, LRP1b and LRP2 as its core members (Fig. 1). These receptors are composed of clusters of ligand binding repeats, EGF-repeats, β-propeller domains, a transmembrane domain as well as a cytoplasmic domain. In addition, the LDL receptor, VLDL receptor and apoE receptor 2 contain an additional O-linked sugar domain. Members of this family are highly conserved both at the DNA and protein levels. Utilizing the NCBI HomoloGene database, we compared the DNA and protein sequences of LDL receptor family members with their putative homologs in 12 eukaryotic species (Fig. 2A). Although homolog annotations are incomplete in some species, as indicated by blank tiles, the DNA and protein sequences of the receptor family are remarkably well conserved in vertebrate animals.

Fig. 1. Core members of the LDL receptor family.

Core members of this receptor family include similar domain organization consisting of ligand binding repeats, epidermal growth factor (EGF) repeats, β-propeller domains, a transmembrane domain and cytoplasmic domains containing one or more NPxY motifs.

Fig. 2. LRP1 and the LDL receptor family are highly conserved.

(A) The percent identity of human DNA and protein sequences for the LDL receptor family members against their predicted homologs in 12 species were retrieved from the NCBI HomoloGene database. Tiles with a black circle indicate that there is currently no annotation for a receptor homolog in the indicated species. The high levels of sequence identity (black) indicate that the family is particularly well conserved in vertebrate species. For example, human LRP1 protein is 92%, 99%, 98%, 98%, 98%, 87%, 83%, 77%, 40% and 41% identical to P.troglodytes, C.lupus, B.taurus, M.musculus, R.norvegicus, G.gallus, X.tropicalis, D.rerio, D.melanogaster and A.gambiae LRP1 homologs. (B) The sequence identity of prominent LRP1 ligands in these species indicate that they are generally less conserved than LRP1 (open circles). This suggests that the biological role of LRP1 extends beyond the interaction with any single ligand.

LRP1 is synthesized as a single chain molecule and is cleaved by furin in the trans-Golgi into a 515 kDa heavy chain and an 85 kDa light chain [26]. The resultant heavy and light chain remain non-covalently associated in the mature receptor. LRP1 is expressed in most cells and tissues and is most abundant in SMC, hepatocytes, fibroblasts, macrophages and neurons [13, 27]. The physiological roles of LRP1 in diverse tissues are in part mediated by the ability of LRP1 to bind and internalize a variety of structurally-diverse ligands. Investigation of LRP1 ligands and their homologs in eukaryotic species reveal that LRP1 trends toward a higher degree of sequence conservation than any single ligand at both the DNA and protein levels (Fig. 2B). We interpret this finding to mean that the functional role of LRP1 is multifaceted and extends beyond the interaction with any single ligand. This conclusion is supported by the association of LRP1 function with numerous diseases based on both clinical studies and in studies employing various mouse models. These include vascular disease (see below), hepatic steatosis [22], insulin resistance (see review [28]) and Alzheimer’s disease (see review [29]).

3. AORTIC ANEURYSMS

The pathobiology of aortic aneurysms is complex and largely unsolved. Unbiased whole genome sequencing is now being used to elucidate the genetic basis of aortic aneurysms to uncover the germline genetic variants that cause or influence the risk of disease. The two types of aortic aneurysms, abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) and thoracic aortic aneurysms (TAA) have different etiologies. Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) are more common and are linked to multiple genetic, environmental and lifestyle-associated risk factors, including hyperlipidemia, hypertension, sex, smoking and age [30–33]. Several genes and loci have been associated with AAA, including LRP1, CDKN2B-AS1, CNTN3, LPA, IL6R and SORT1, MMP3 [31, 34, 35]. Thoracic aortic aneurysms (TAA) are much rarer and have a stronger linkage to genetic factors, and the numerous causal genes thus far identified point to the importance of the maintenance of interaction between vascular SMC and the medial ECM. These genes include matrix components (FBN1, EFEMP2, COL3A1), components of the TGFβ signaling pathway (TGFBR1, TGFBR2, SMAD3, TGFB2), and smooth muscle cell genes that are involved in the contractile process (ACTA2, MYH11, MYLK ) [36–39].

4. GENETIC STUDIES IN HUMANS LINK LRP1 TO ANEURYSMS

Genetic studies, including genome-wide association studies (GWAS), exome sequencing, and TaqMan single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping assays, have revealed the association of LRP1 SNPs with aortic aneurysms, aortic dissections, and Marfan Syndrome (Table 1). In a seminal GWAS, Bown et al. [40] demonstrated a significant association of a LRP1 SNP, rs1466535, with AAA. Additional independent association studies of coronary artery disease, blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, or diabetes showed no association with rs1466535 or the 12q13.3 locus, suggesting a specific association of the locus with AAA. Bown et al. [40] also confirmed during the replication stage that the SNP rs1466535 risk allele is the C allele. Association of LRP1 SNPs with AAA was confirmed in a separate GWAS by Bradley et al. [41]. The discovery stage revealed suggestive association (p-value < 1 × 10−4) of two SNPs within the 12q13.3 locus with AAA, rs4759044 (p = 5.40 × 10−5) and rs1466535 (p = 2.12 × 10−5). In contrast to the GWAS by Bown et al. [40], the SNP rs1466535 risk allele reported by Bradley et al. [41] is the A allele. Interestingly, a separate study [42] involving TaqMan SNP genotyping of an Italian population showed a significant (p = 0.01) association of the rs1466535 polymorphism with AAA, but the study reported a T risk allele for the locus. In a recent meta-analysis of GWAS for AAA [35], the previously reported LRP1 SNPs associated with AAA were not replicated. A newly identified SNP within the 12q13.3 locus, rs1385526, showed border-line association with AAA. Although the SNP reached the discovery threshold of significance (p = 1.1 × 10−9), it failed to reach the genome-wide threshold of significance when combined with the validation cohort (p = 6.4 × 10−7). Although these studies reported different SNPs within the 12q13.3 locus and risk alleles associated with AAA, these results confirm that polymorphisms of the LRP1 gene is a susceptibility factor for AAA. It is likely that reported differences in association significance (i.e. p-values) and risk alleles are largely attributed to population availability and variation. Importantly, biological evidence and association with other vascular diseases support the role of LRP1 in AAA and warrant further investigation. Variants in LRP1 have also been shown to be associated with aortic dissections. In a GWAS, Debette et al. [43] identified two LRP1 SNPs associated with cervical artery dissections, rs11172113 (p = 3.03 × 10−7) and rs1466535 (p = 4.94 × 10−6). Interestingly, the same SNP rs11172113, identified through exome sequencing, was significantly associated with a decreased risk for sporadic thoracic aortic dissection (STAD) (p = 2.74 × 10−8) and type A dissection alone (p = 3.11 × 10−6) [44]. These studies demonstrate that different LRP1 variants can be associated with an increased risk for specific vascular diseases or confer protection.

Table 1.

Genetic studies of LRP1 associated with aortic aneurysms, aortic dissections, and disease.

| SNP | Functional Class | Risk Allele | OR (95% CI) | p-value | Method | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aortic Aneurysms | |||||||

| Abdominal | rs1466535 | Intron | C | 1.15 (1.10–1.21) | 4.52 × 10−10 | GWAS | [40] |

| rs4759044 | Intron | G | 0.85 (0.79–0.92) | 5.40 × 10−5 | GWAS | [41] | |

| rs1466535 | Intron | A | 0.84 (0.77–0.91) | 2.12 × 10−5 | GWAS | [41] | |

| rs1466535 | Intron | T | 1.85 (1.2–2.84) | 0.01 | TaqMan | [42] | |

| rs1385526 | Intron | C | 0.91 (0.877–0.944) | 6.4 × 10−7 | GWAS | [35] | |

| Aortic Dissections | |||||||

| Cervical Artery | rs11172113 | Intron | C | 0.82 (0.76–0.89) | 3.03 × 10−7 | GWAS | [43] |

| rs1466535 | Intron | A | 0.83 (0.77–0.90) | 4.94 × 10−6 | GWAS | [43] | |

| Sporadic Thoracic Type A + B | rs11172113 | Intron | C† | 0.82 (0.76–0.89) | 2.74 × 10−8 | Exome | [44] |

| Sporadic Thoracic Type A | rs11172113 | Intron | C† | 0.81 (0.75–0.89) | 3.11 × 10−6 | Exome | [44] |

| Other Diseases | |||||||

| Marfan Syndrome | n/a | Exon | A | n/a | n/a | Exome | [45] |

Minor allele associated with a decreased risk. n/a: Not applicable

Connective tissue disorders, such as Marfan syndrome, often involve cardiovascular complications including aortic aneurysms and dissections, mitral valve prolapse, and aortic regurgitation. Exome sequencing of two Marfan syndrome patients from a four-generation Marfan syndrome family identified a missense mutation (G > A) in exon 15 of LRP1 [45]. This study further supports the involvement of the LRP1 gene in aortic aneurysms and dissections and provides an additional target for further pathobiological research.

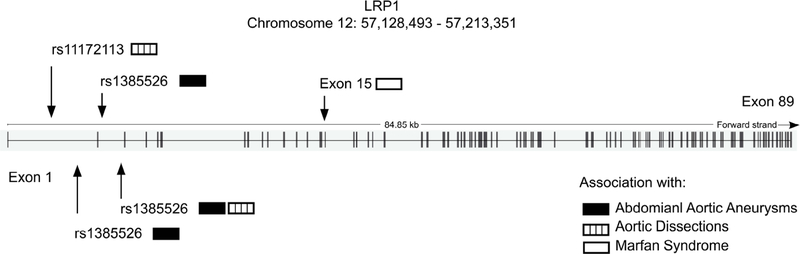

The human LRP1 gene is located on chromosome 12 and contains 89 exons (Ensembl Release 89 – May 2017; Gene ENSG00000123384; Transcript ID ENST00000243077.7). A majority of the LRP1 variants cataloged in Homo sapiens [46]. occur within introns of the gene. Furthermore, LRP1 SNPs associated with AAA or aortic dissections are located within the first two introns (Fig. 3). Gene expression studies by Bown et al. [40] showed a trending increase in LRP1 expression with the rs1466535 CC genotype in sampled arterial tissues and a significant (p = 0.029) increase (1.19-fold [1.04–1.36]) in LRP1 expression in the aortic adventitia of CC homozygotes compared to TT homozygotes. Additional functional studies suggested that rs1466535 may alter a SREBP-1 binding site and influence enhancer activity [40]. In contrast to the LRP1 SNP locations associated with AAA or aortic dissections, the LRP1 SNP associated with Marfan syndrome was mapped to exon 15. Exon 15 corresponds to an EGF repeat located between a β-propeller (YWTD) domain and cluster II on the LRP1 ectodomain, and a missense mutation at this location may affect ligand binding. Collectively, genetic studies have demonstrated a significant association of LRP1 SNPs with AAA, aortic dissections, and Marfan syndrome; however, additional functional studies are necessary to elucidate the effect of these polymorphisms on ligand binding and/or signaling pathways.

Fig. 3. LRP1 gene structure and mapped SNPs.

The human LRP1 gene contains 89 exons and is located on chromosome 12q13.3. Genetic studies have revealed the association of LRP1 SNPs with abdominal aortic aneurysms (black), aortic dissections (open), and Marfan Syndrome (dotted). LRP1 SNPs associated with abdominal aortic aneurysms or aortic dissections are located within the first two introns while the LRP1 SNP associated with Marfan Syndrome, a missense mutation (G > A), is located in exon 15. (Ensembl Release 89 – May 2017; Gene ENSG00000123384; Transcript ID ENST00000243077.7).

Of interest in this regard are the studies of Chan et al., [47] who reported a significant reduction in protein levels of LRP1 in human AAA samples associating LRP1 with AAA pathogenesis. Recently, Chan et al. [48] demonstrated that translational inhibition by microRNA-205 was responsible for driving the lower expression levels of LRP1. Furthermore, lower levels of LRP1 were speculated to result in accumulation of excess matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9, a well-documented protease that contributes to the degradation of the extracellular matrix proteins leading to AAA [49].

5. A PARADOXICAL ROLE FOR TGFβ SIGNALING IN THE VASCULATURE

The role of TGFβ signaling in vascular development and its subsequent contribution to the development of vascular disease is still not fully understood. First of all, studies in mice have revealed that TGFβ signaling is absolutely required for appropriate vascular development, and global loss of TGFβ signaling or selective ablation of TGFβ signaling in SMC during development leads to embryonic lethality due to severe vascular defects [50–53]. An important role for TGFβ signaling during vascular development is to facilitate SMC differentiation. Interestingly, conditional deletion of Tgfbr2 [54, 55] or Smad4 [56] in SMC following birth results in aneurysm formation, revealing that TGFβ signaling is not only required for vascular development, but is also essential for vessel wall homeostasis in postnatal mice.

In apparent contradiction to these results, mouse models have revealed that excess TGFβ signaling promotes TAA and dissections in a mouse model of Marfan syndrome [57–59] as well as in mouse models of Loeys-Dietz syndrome [60]. This occurs via non-canonical TGFβ signaling resulting in activation of the ERK1/2 and JNK1 pathways [61]. While all of the complexities of TGFβ signaling in the vasculature are far from being resolved, an elegant study of Cook et al. [62]. provides significant insight into the essential role of TGFβ signaling during vascular development along with the harmful effects of excess signaling following development of the vasculature. This study found that neutralizing TGFβ signaling in mice prior to postnatal day 16 exacerbated TAA formation, while neutralizing TGFβ signaling following postnatal day 45 reduced TAA formation. Taken together, these studies reveal that tight regulation of TGFβ signaling pathways is essential for vascular development as well as for maintenance of the vessel wall, and that deregulation of TGFβ signaling leads to disease.

A pivotal discovery employing a Marfan mouse model was the finding that administration of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonist, losartan corrected ascending aortic dilatation through its ability to attenuate TGFβ signaling [58]. Interestingly, losartan was much more effective than β-adrenergic blocking agents, such as propranolol in this capacity [58]. These exciting results have led to clinical trials examining the effectiveness of losartan for the treatment of Marfan syndrome including the “Atenolol versus losartan in children and young adults” trial [63]. The results of this study revealed no significant difference between these two treatments, and thus the dramatic results of losartan therapy over those of β-blockers observed in Marfan mice were not duplicated inpatient studies, perhaps for a variety of reasons [64].

6. LRP1 PROTECTS THE VASCULATURE

A protective role for LRP1 is well documented in numerous vascular beds. Under hypercholesterolemic conditions in cholesterol-fed LDL receptor-deficient mice, Boucher et al. showed an increase in vascular occlusion in mice in which the Lrp1 gene was specifically deleted in vascular SMC. This effect was attributed to excess activation of the PDGF-signaling pathway [6]. Selective deletion of LRP1 in macrophages also resulted in the development of more extensive atherosclerosis [17–20]. Further, extensive vascular remodeling in these mice was noted employing a carotid ligation model [21]. At present, it is not clear how macrophage LRP1 modulates these processes. It does appear, however, that macrophage LRP1 regulates the TGFβ signaling pathway [21], macrophage migration [65] and inflammation [66]. In the brain, LRP1 plays an important role as a key clearance receptor for amyloid-β by endothelial cells as well as SMC of the cerebrovasculature [67–69].

Finally, studies have identified LRP1 as a major SMC receptor that plays a critical role in maintaining the integrity of the vessel wall to prevent aneurysm formation [8, 70]. In mice, genetic deletion of LRP1 in smooth muscle cells results in the development of spontaneous thoracic aneurysms, as well as progressive aortic root growth and aberrant thickening of the aortic media with fragmentation and disarray of elastic fibers [8, 70, 71]. While the mechanisms are currently not fully understood, it is clear that LRP1’s ability to regulate protease activity and to modulate signaling pathways contribute to this protective role.

7. LRP1 PLAYS A MAJOR ROLE IN REGULATING THE LEVELS OF PROTEASES

Studies have revealed that LRP1 plays a major role in regulating the levels of numerous proteases, protease inhibitors, protease cofactors and complexes of proteases with their inhibitors (Table 2). For certain proteases, their regulation by LRP1 occurs when the protease directly binds LRP1 on the cell surface and is then transported into the cell where it is delivered to lysosomal compartments for subsequent degradation. Interestingly, proteases thus far known to directly bind to LRP1 include those involved in the degradation of the extracellular matrix as well as those involved in blood coagulation and fibrinolysis. Secreted metalloproteinases that degrade the matrix whose levels are regulated by LRP1 include ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5, MMP-13, MMP9 and MMP2. ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5 degrade proteoglycans including Aggrecan, a major component of cartilage. Excess activity of these proteases leads to degradation of Aggrecan, which is a significant event in early stages of osteoarthritis [72, 73]. MMP-13 is thought to play a critical role in the degradation of cartilage and also contributes to the early phases of osteoarthritis [74]. MMP-9 and MMP-2 are involved in tissue remodeling and inflammation [75] and evidence suggests that both proteases can contribute to the development of AAA [76]. Interestingly, MMP-2 is upregulated in tissue from patients with TAA and aortic dissections [77], and serum levels of MMP-2 correlate with ascending aortic diameter in patients with ascending aortic aneurysms [78]. MMP-2 does not directly bind LRP1, but does bind tightly to thrombospondin 2, which then can interact with LRP1 to mediate the cellular internalization of the complex [78]. Finally, LRP1 also regulates the levels of high temperature requirement A1 (HtrA1) [8], a secreted serine protease that attenuates TGFβ signaling and also degrades components of the extracellular matrix [80]. HtrA1 levels increase dramatically in mice in which LRP1 is genetically deleted in SMC [8].

Table 2.

Proteases, co-factors, protease inhibitors and protease-inhibitor complexes that bind to LRP1.

| Function | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Proteases that degrade the extracellular matrix | ||

| ADAMTS-4 | Degrades cartilage proteoglycans | [116] |

| ADAMTS-5 | Degrades cartilage proteoglycans | [117] |

| MMP-13 | Degrades extracellular matrix | [118] |

| MMP-9 | Local proteolysis of extracellular matrix | [119] |

| TSP-2:MMP-2 complexes | Degrades extracellular matrix | [79] |

| HtrA1 | Degrades extracellular matrix | [8] |

| Proteases and cofactors involved in blood coagulation | ||

| Factor IXa | Blood coagulation | [120] |

| Factor VIII | Blood coagulation | [121, 122] |

| Factor V | Blood coagulation | [123] |

| Proteases involved in fibrinolysis | ||

| tPA | Fibrinolysis | [79, 124] |

| Pro-uPA and uPA | Fibrinolysis | [125] |

| Protease inhibitors that regulation blood coagulation | ||

| Heparin cofactor II:thrombin complexes | Regulation of blood coagulation | [126] |

| ATIII-thrombin complexes | Regulation of blood coagulation | [126] |

| Protein C inhibitor:protease complexes | Regulation of blood coagulation | [127] |

| TFPI and TFPI:fVIIa complexes | Regulation of blood coagulation | [128] |

| Protease nexin 1:protease complexes | Regulation of blood coagulation, development | [129] |

| Protease inhibitors that regulate fibrinolysis | ||

| PAI-1 and PAI-1:protease complexes | Regulation of fibrinolysis | [130] |

| Neuroserpin and Neuroserpin:protease complexes | Plasminogen activator inhibitor in brain, synaptic plasticity | [131] |

| Pan-protease inhibitors and inhibitors that regulate inflammation and complement activation | ||

| Activated α2M and α2M-protease complexes | Inflammation, pan-protease inhibitor | [10, 11] |

| PZP protease complexes | Pan-protease inhibitor | [132] |

| C1s:C1 inhibitor | Regulation of complement activation | [133] |

| α1-antitrypsin:protease complexes | Neutrophil elastase inhibitor, protects against inflammation and matrix degradation | [126] |

| Protease inhibitors that regulate matrix degradation | ||

| Timp3 | Regulation of matrix degradation | [134] |

In addition to binding and mediating the cellular internalization of matrix-degrading proteases, LRP1 also regulates the levels of several proteases and co-factors involved in blood coagulation and fibrinolysis. These include factor fVIII, a co-factor protein whose deficiency leads to hemophilia A. Upon activation of fVIII to fVIIIa by the enzyme thrombin, fVIIIa associates with fIXa to form a proteolytic complex responsible for activating factor X to Xa. Factor Xa in complex with fVa are the final enzymes responsible for generating thrombin, the terminal protease in the blood coagulation cascade. In addition to regulating thrombosis by removing factors VIII and IXa, LRP1 also binds the plasminogen activators urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) as well as tissue-type plasminogen activator.

Protease activity is tightly regulated by inhibitors. In the circulation, most protease inhibitors belong to the Serpin family of inhibitors. Early work by Ohlsson and colleagues [81] investigating the clearance of trypsin-inhibitor complexes from the circulation suggested the existence of an hepatic receptor responsible for the clearance of serpin-enzyme complexes. We now know that LRP1 is responsible for binding and mediating the removal of a number of serpin-enzyme complexes (Table 2). Most of these inhibitors only bind to LRP1 as a complex with a protease, but PAI-1 [82] and neuroserpin [83] appear capable of binding directly to LRP1 without a proteinase. Of interest, the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 3 (TIMP3) also binds directly to LRP1 [84]. TIMP3 is an important inhibitor of several metalloproteinases.

8. SIGNALING PROPERTIES OF LRP1

Similar to the diversity of LRP1 ligands, LRP1 modulates a wide variety of signaling pathways, including the PDGF [85, 86], TGFβ [21, 87, 88] and MAPK signaling pathways [89, 90], as well as the activation of Src family kinases [91], and the mediation of the bone morphogenic protein-binding endothelial regulator (BMPER) signaling pathway [92]. One mechanism by which LRP1 can precisely activate a wide array of signaling pathways is via interaction with co-receptors. In this paradigm, LRP1 ligands either recruit co-receptors via direct interaction with the co-receptor or induce conformational changes in LRP1 upon binding that enable LRP1 to interact with co-receptors. Co-receptor association with LRP1 results in the recruitment of additional scaffolding proteins [90], the phosphorylation of tyrosine residues within the LRP1 cytoplasmic domain [85, 86], and activation of specific signaling pathways [93]. Despite significant progress, mechanisms by which LRP1 regulates signaling pathways are still not fully understood.

8.1. Proteases and Protease Inhibitors as LRP1 Signaling Mediators

In addition to their role in degradation of the extracellular matrix, proteases and protease inhibitors compose a major class of LRP1 ligands that can initiate signaling events. In bone-marrow-derived macrophages, LRP1 has been demonstrated to regulate the inflammatory response by modulating NFκB activation [66] (Table 3). Initial studies discovered that the response of macrophages to LPS was significantly enhanced when LRP1 was genetically deleted. Interestingly, both tissue-type plasminogen activator tPA (or an enzymatically inactive form of tPA) and activated forms of α2-macroglobulin (α2M*) inhibited the response of BMDM to lipopolysaccharide (LPS). This occurs via a process in which these two ligands prevent the LPS-mediated phosphorylation of IκBα, a key regulator of the NF-kB pathway. Late in the canonical NF-κB pathway, IκBα is phosphorylated and then tagged for proteasomal degradation. IκBα degradation then allows translocation of the p50/p65 phosphorylated complex to the nucleus to induce transcription of NF-κB regulated genes.

Table 3.

LRP1-mediated signaling pathways.

| Primary Ligands | Co-receptors | Function | Pathway Interactions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tPA or α2M | Trk NMDAR |

Fibrosis, inflammation, cell survival | ERK1/2, SFK, RhoA, PI3K, NF-κB, PSD-95, | [16, 66, 90, 91, 107, 111] |

| MMP-9 | Cell migration, Peripheral nervous system injury | ERK1/2, PI3K | [89] | |

| PAI-1 | Cell survival, cell migration | ERK1/2, β-catenin, PI3K, JAK1/STAT1,vitronectin, integrin αvβ3 | [97, 98, 100] | |

| uPA | EGFR | Cell migration, fibrosis | ERK | [99] |

| TGF-β | TGF-βRI TGF-βRII Decorin |

Cell growth, matrix remodeling | Smad2/3, ERK1/2 | [21, 87, 88, 101, 102, 106] |

| PDGF | PDGFR-β | Aneurysm formation | ERK1/2, Shc, SFKs | [85, 86] |

| CTGF | Fibrosis, fibroblast differentiation | ERK1/2, Akt | [115] | |

| BMPER | Angiogenesis, endothelial cell proliferation, cell cycle progression | PARP-1, CDK2, Rb, NFATc1, ERK, INF-γ, NF-κB, NF45 | [24, 92] | |

| Frizzled | Frizzled-1 | Tissue development | Wnt3A, LRP6 | [112] |

Studies have also revealed that another protease, matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) also interacts with LRP1 to initiate a signaling cascade that may be significant in regulating Schwann cell migration upon peripheral nervous system injury [89]. This study observed that association of the MMP9 hemopexin domain with LRP1 activates a MAPK signaling cascade. Silencing of LRP1 or inhibition of MMP-9 hemopexin domain binding with receptor associated protein (RAP) which binds to LRP1 at multiple sites and inhibits its ability to bind ligands [94–96] prevented activation of Akt and ERK1/2 in Schwann cells. The MMP-9 signaling effect is not generalizable to other MMPs since MMP-2, which is not recognized by LRP1, did not induce activation of Akt and ERK1/2. Interestingly, in a crush injury model of peripheral nervous system injury, LRP1-dependent MMP-9 signaling was specific to only injured sciatic nerves with no noticeable pathway effects on undamaged nerves.

Prior studies have shown that the protease inhibitor plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) can block SMC migration by regulating the accessibility of cell associated integrin attachment sites in the matrix [97]. This occurs when PAI-1 associates with vitronectin to block its interaction with integrin αvβ3. Interestingly, formation of a complex of PAI-1 with plasminogen activators results in loss of affinity of PAI-1 for vitronectin and restores cell migration. In addition to inhibiting SMC migration by blocking integrin binding sites in the matrix, PAI-1 can also stimulate cell migration via an LRP1-dependent mechanism [98]. Degryse et al. [98] demonstrated that PAI-1 stimulated rat SMC migration and this was attributed to the ability of either active or cleaved PAI-1 to mediate activation of the JAK/STAT signaling system. The effect of PAI-1 on LRP1-induced cell migration of rat SMC was independent of uPA, uPa receptor (uPAR), or vitronectin [98, 99]. More recent studies have suggested that PAI-1 also appears capable of modulating cell migration via an LRP1-dependent activation of β-catenin and ERK1/2 MAPK pathway [100]. Interestingly, PAI-1 induced transcription of beta-catenin-related genes in mouse embryonic fibroblasts expressing LRP1, but not in mouse embryonic fibroblasts deficient in LRP1.

8.2. Attenuation of TGFβ Signaling by LRP1

Several studies support the notion that LRP1 is an important modulator of the TGFβ signaling pathway. Initial studies by Huang et al. [101] demonstrated that 125I-labeled TGFβ1 could be crosslinked to LRP1, and further demonstrated that murine fibroblasts in which LRP1 was genetically deleted were not sensitive to growth inhibition by TGFβ [101](Table 3). Further confirmation came from the studies of Tseng et al. [102] who demonstrated that TGFβ 1 inhibits the growth of wild-type Chinese hamster ovary cells, but not the growth of LRP1-deficient Chinese hamster ovary cells. In vivo evidence that LRP1 modulates the TGFβ signaling pathway is derived from vascular remodeling studies in mice in which LRP1 was selectively deleted from macrophages [21]. In these studies, macrophage LRP1 was found to protect the vasculature by limiting remodeling events associated with injury. This resulted from the ability of macrophage LRP1 to reduce TGF β2 protein levels and to attenuate expression of the TGF-β2 gene, resulting in suppression of the TGFβ signaling pathway.

It is not clear how LRP1 attenuates the TGFβ signaling pathway. One possibility is that LRP1 regulates levels of TGFβ ligands by mediating their internalization. This notion is supported by surface plasmon resonance experiments revealing that TGFβ2 binds to LRP1 with affinity values close to those measured for the binding of TGFβ1 to soluble forms of TGFBR2 [21]. Furthermore, TGFβ2 is crosslinked to LRP1 in macrophages, and TGFβ2 antigen accumulates in conditioned media of LRP1-deficient macrophages [21]. In addition to its ability to reduce TGFβ levels, LRP1 also appears to attenuate gene expression as well [21], and very likely modulates the TGFβ signaling pathway by additional mechanisms.

Studies have revealed that the role of LRP1 in regulating TGFβ signaling pathways often involve other molecules. For example, studies have shown that LRP1 functions as an endocytic receptor for decorin [103, 104], a small leucine-rich proteoglycan that is known to modulate TGFβ signaling pathways [105]. Interestingly, Cabello-Verrugio and Brandan discovered a novel modulatory signaling pathway requiring both activation of the Smad pathway and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in which decorin and LRP1 cooperate to modulate TGFβ signaling responses in myoblasts [106].

8.3. Co-receptor Involvement in LRP1 Signaling

LRP1 is capable of assembling unique co-receptor complexes that depend upon the specific ligand [90]. For example, studies found that treating PC12 and N2a neuron-like cells with tPA (or enzymatically inactive tPA) or α2M* resulted in rapid activation of ERK1/2 that was completely blocked by the LRP1 antagonist RAP [90]. tPA or α2M* treatment also resulted in phosphorylation of the tyrosine receptor kinase (Trk) receptors. All of these processes seemed to require the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) [90]. Together, these studies suggested that NMDARs cooperate with LRP1 in mediating the activation of the MAPK pathway. This cooperation may involve cytoplasmic adaptor proteins as studies have demonstrated that LRP1 can co-precipitate with NMDAR and postsynaptic density protein 95 [16, 107]. Interestingly, the tPA or α2M* mediated signaling events described above were ligand specific, as myelin-associated glycoprotein, another LRP1 ligand, failed to mediate the activation of ERK1/2 or induce phosphorylation of TrkA. In contrast, the association of myelin-associated glycoprotein with LRP1 stimulated a completely different signaling pathway, which was accomplished by recruiting the p75 neurotrophin receptor into a complex with LRP1 resulting in the formation of activated RhoA [90].

A second example for a ligand-induced co-receptor function for LRP1 involves the PDGF signaling pathway. Initial studies [85] demonstrated that PDGF-BB directly binds to LRP1 and promotes transient tyrosine phosphorylation of the LRP1 cytoplasmic domain. This process requires activation of the PDGF receptor and activation of Src. Employing immunofluorescence and immunogold electron microscopy experiments, LRP1 and PDGF receptor-β were subsequently demonstrated to co-localize in coated-pits and endosomal compartments [86, 108]. Furthermore, phosphorylated forms of the PDGFR-β co-precipitated with LRP1 [108]. Interestingly, phosphorylation of LRP1 is blocked by treating the cells with dynamin inhibitors to prevent endocytosis [86]. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the LRP1 cytoplasmic domain generates a binding site on LRP1 for the adaptor proteins Shc [85, 109] and SHP-2 [110], a cytoplasmic SH2 domain containing protein tyrosine phosphatase, thereby modulating PGDF-mediated signaling events.

In addition to co-receptor complex formation, LRP1 can initiate signaling pathways by trans-activation of a second receptor. For example, ligand binding to LRP1 in embryonic sensory neurons results in the activation of Src family kinase members, which in turn mediated the transactivation of Trk receptors and lead to the activation of ERK1/2 and Akt [91]. Transfection of cells with a kinase-defective Src prevented phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and Akt. This signaling pathway is required for neurite sprouting in embryonic sensory neurons [111]. Finally, studies have also demonstrated that LRP1 interact with frizzled-1, a key co-receptor in the canonical Wnt signaling pathway [112]. This interact results in the formation of an inhibitory complex leading to suppression of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway.

8.4. CTGF-mediated LRP1 Signaling

Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2) is a small cysteine-rich protein that is a member of the CCN family [113]. CTGF plays a variety of roles in the vasculature and contributes to angiogenesis, fibrogenesis, atherosclerosis and restenosis. Segarini et al. [114] were the first to identify LRP1 as a receptor for CTGF. CTGF protein levels, but not mRNA levels, were significantly increased in mice in which LRP1 was selectively deleted in SMC [8]. While not fully understood at present, LRP1 does influence signaling events mediated by CTGF. Thus, in renal myofibroblasts, CTGF mediates the tyrosine phosphorylation of the LRP1 cytoplasmic domain, an event that is required for the synergistic effect of CTGF and TGF-β to activate ERK1/2 and induce expression of α-SMA in these cells [115].

CONCLUSIONS

As a cellular receptor, LRP1 has the capacity to modulate an enormous number of biological processes, both by binding and removing molecules targeted for degradation and by initiating specific signaling pathways. The two major classes of ligands for this receptor, lipoproteins and proteases, contribute to important physiological processes. The diversity of LRP1 function arises from its capacity to interact with numerous ligands as well as other transmembrane proteins to affect specific biological processes. Ligand-mediated assembly of co-receptors to participate along with LRP1 in signaling events provides remarkable specificity and diversity to this receptor’s function. Evidence is beginning to accumulate revealing a critical function for this receptor in maintaining the integrity of the vasculature. This evidence includes genetic studies in humans as well as in mouse models in which the LRP1 gene has been selectively deleted in various cells. Defining the endocytic and signaling functions of LRP1 and how they integrate at the molecular level to affect cellular processes will require additional studies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Cancer Institute, the National Institutes of Health (R35 HL135743, Dudley K. Strickland; F31 HL131293, Dianaly T. Au; F31CA213815 William E. Fondrie), and the American Heart Association Scientist Development Award (15SDG244 70170, Selen C. Muratoglu).

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- LDL

Low density lipoprotein

- LRP

LDL receptor-related protein

- SMC

Smooth muscle cells

- RAP

Receptor associated protein

- TGFβ

Transforming growth factor β

- EGF

Epidermal growth factor

- TAA

Thoracic aortic aneurysms

- AAA

Abdominal aortic aneurysms

- GWAS

Genome-wide association study

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- MMP

Matrix metalloprotease

- ERK

Extracellular signal-regulated kinases

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- ADAMTS

A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin type 1 motif

- HtrA1

High temperature requirement A1

- PDGF

Platelet derived growth factor

- PAI-1

Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

- TIMP3

Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3

- Trk

Tyrosine receptor kinase

- NMDAR

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor

Footnotes

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- [1].N. C. for H. S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Underlying Cause of Death 1999–2015 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released December, 2016,” Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999–2015, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucdicd10.html on Jul 13, 2017 11:00:55, 2017.N.C 2017.

- [2].Humphrey JD, Schwartz MA, Tellides G, Milewicz DM. Role of mechanotransduction in vascular biology: focus on thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. Circ Res 2015; 116(8):1448–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mecham RP. Elastin synthesis and fiber assembly. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1991; 624: 137–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mithieux SM, Weiss AS. Elastin. Adv Protein Chem 2005; 70: 437–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Karimi A, Milewicz DM. Structure of the elastin-contractile units in the thoracic aorta and how genes that cause thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections disrupt this structure. Can J Cardiol 2016; 32(1): 26–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Boucher P, Gotthardt M, Li WP, Anderson RGW, Herz J. LRP: Role in vascular wall integrity and protection from atherosclerosis. Science 2003; 300(5617): 329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Basford JE, Moore ZW, Zhou L, Herz J, Hui DY. Smooth muscle LDL receptor-related protein-1 inactivation reduces vascular reactivity and promotes injury-induced neointima formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2009; 29(11): 1772–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Muratoglu SC, Belgrave S, Hampton B, et al. LRP1 Protects the Vasculature by Regulating Levels of Connective Tissue Growth Factor and HtrA1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2013; 33(9):2137–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Boucher P, Li WP, Matz RL, et al. LRP1 functions as an atheroprotective integrator of TGFbeta and PDFG signals in the vascular wall: Implications for marfan syndrome. PLoS One 2007; 2:e448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ashcom JD, Tiller SE, Dickerson K, et al. The human α2-macroglobulin receptor: identification of a 420-kD cell surface glycoprotein specific for the activated conformation of α2-macroglobulin. J Cell Biol 1990; 110: 1041–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Strickland DK, Ashcom JD, Williams S, et al. Sequence identity between the α2-macroglobulin receptor and low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein suggests that this molecule is a multifunctional receptor. J Biol Chem 1990; 265: 17401–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Herz J, Strickland DK. LRP: a multifunctional scavenger and signaling receptor. J Clin Invest 2001; 108(6): 779–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lillis AP, Van Duyn LB, Murphy-Ullrich JE, Strickland DK. LDL receptor-related protein 1: Unique tissue-specific functions revealed by selective gene knockout studies. Physiol Rev 2008; 88(3):887–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Herz J, Clouthier DE, Hammer RE. Correction: LDL receptor-related protein internalizes and degrades uPA-PAI-1 complexes and is essential for embryo implantation. Cell 1993; 73: 428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nakajima C, Haffner P, Goerke SM, et al. The lipoprotein receptor LRP1 modulates sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling and is essential for vascular development. Development 2014; 141(23): 4513–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].May P, Rohlmann A, Bock HH, et al. Neuronal LRP1 functionally associates with postsynaptic proteins and is required for normal motor function in mice. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24(20): 8872–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hu L, Boesten LS, May P, et al. Macrophage low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein deficiency enhances atherosclerosis in ApoE/LDLR double knockout mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2006; 26(12):2710–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Overton CD, Yancey PG, Major AS, Linton MF, Fazio S. Deletion of macrophage LDL receptor-related protein increases atherogenesis in the mouse. Circ Res 2007; 100(5): 670–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yancey PG, Blakemore J, Ding L, et al. Macrophage LRP-1 controls plaque cellularity by regulating efferocytosis and Akt activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2010; 30(4): 787–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Yancey PG, Ding Y, Fan D, et al. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 prevents early atherosclerosis by limiting lesional apoptosis and inflammatory Ly-6Chigh monocytosis: evidence that the effects are not apolipoprotein E dependent. Circulation 2011; 124(4):454–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Muratoglu SC, Belgrave S, Lillis AP, et al. Macrophage LRP1 suppresses neo-intima formation during vascular remodeling by modulating the TGF-ß signaling pathway. PloS One 2011; 6(12):e28846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ding Y, Xian X, Holland WL, Tsai S, Herz J. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 protects against hepatic insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis. EBioMedicine 2016. May; 7:135–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hamlin AN, Basford JE, Jaeschke A, Hui DY. LRP1 protein deficiency exacerbates palmitate-induced steatosis and toxicity in hepatocytes. J Biol Chem 2016; 291(32):16610–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mao H, Lockyer P, Townley-Tilson WH, Xie L, Pi X. LRP1 regulates retinal angiogenesis by inhibiting parp-1 activity and endothelial cell proliferation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2016; 36(2): 350–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Storck SE, Meister S, Nahrath J, et al. Endothelial LRP1 transports amyloid-beta1–42 across the blood-brain barrier. J Clin Invest 2016; 126(1): 123–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Herz J, Kowal RC, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Proteolytic processing of the 600 kD low density liprotein receptor related protein LRP occurs in a trans-Golgi compartment. EMBO J 1990; 9: 1769–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Etique N, Verzeaux L, Dedieu S, Emonard H. LRP-1: a checkpoint for the extracellular matrix proteolysis. Biomed Res Int 2013; 2013: 152163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Au DT, Strickland DK, Muratoglu SC. The LDL Receptor-Related Protein 1: At the Crossroads of Lipoprotein Metabolism and Insulin Signaling. J Diabetes Res 2017; 2017: 8356537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Bu G Apolipoprotein E and its receptors in Alzheimer’s disease: pathways, pathogenesis and therapy. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009; 10(5): 333–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kuivaniemi H, Shibamura H, Arthur C, et al. Familial abdominal aortic aneurysms: collection of 233 multiplex families. J Vasc Surg 2003; 37(2): 340–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kuivaniemi H, Ryer EJ, Elmore JR, et al. Update on abdominal aortic aneurysm research: from clinical to genetic studies. Scientifica (Cairo ) 2014; 2014: 564734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2013; 127(1): e6–e245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cornuz J, Sidoti PC, Tevaearai H, Egger M. Risk factors for asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm: systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based screening studies. Eur J Public Health 2004; 14(4): 343–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Golledge J, Kuivaniemi H. Genetics of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2013. May; 28(3):290–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Jones GT, Tromp G, Kuivaniemi H, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for abdominal aortic aneurysm identifies four new disease-specific risk loci. Circ Res 2017; 120(2): 341–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Gillis E, Van LL, Loeys BL. Genetics of thoracic aortic aneurysm: at the crossroad of transforming growth factor-beta signaling and vascular smooth muscle cell contractility. Circ Res 2013; 113(3): 327–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Pomianowski P, Elefteriades JA. The genetics and genomics of thoracic aortic disease. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2013; 2(3): 271–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Morisaki T, Morisaki H. Genetics of hereditary large vessel diseases. J Hum Genet 2016; 61(1): 21–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Milewicz DM, Guo DC, Tran-Fadulu V, et al. Genetic basis of thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections: focus on smooth muscle cell contractile dysfunction. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2008; 9: 283–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Bown MJ, Jones GT, Harrison SC, et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysm is associated with a variant in low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1. Am J Hum Genet 2011; 89(5): 619–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bradley DT, Hughes AE, Badger SA, et al. A variant in LDLR is associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2013; 6(5): 498–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Galora S, Saracini C, Pratesi G, et al. Association of rs1466535 LRP1 but not rs3019885 SLC30A8 and rs6674171 TDRD10 gene polymorphisms with abdominal aortic aneurysm in Italian patients. J Vasc Surg 2015; 61(3):787–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Debette S, Kamatani Y, Metso TM, et al. Common variation in PHACTR1 is associated with susceptibility to cervical artery dissection. Nat Genet 2015; 47(1): 78–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Guo D-C, Grove-Gaona M, Prakash S, et al. Genetic variants in LRP1 and ULK4 are associated with acute thoracic aortic dissections. Am J Hum Genet 2016; 99(3): 762–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Li G, Yu J, Wang K, et al. Exome sequencing identified new mutations in a Marfan syndrome family. Diagn Pathol 2014; 9: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Database of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (dbSNP). Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine; (dbSNP Build ID: 150). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/ 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Chan CY, Chan YC, Cheuk BL, Cheng SW. A pilot study on low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 in Chinese patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2013; 46(5): 549–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Chan CY, Chan YC, Cheuk BL, Cheng SW. Clearance of matrix metalloproteinase-9 is dependent on low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 expression downregulated by microRNA-205 in human abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg 2017; 65(2): 509–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Sakalihasan N, Delvenne P, Nusgens BV, Limet R, Lapiere CM. Activated forms of MMP2 and MMP9 in abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg 1996; 24(1): 127–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Frutkin AD, Shi H, Otsuka G, et al. A critical developmental role for tgfbr2 in myogenic cell lineages is revealed in mice expressing SM22-Cre, not SMMHC-Cre. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2006; 41(4): 724–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Langlois D, Hneino M, Bouazza L, et al. Conditional inactivation of TGF-beta type II receptor in smooth muscle cells and epicardium causes lethal aortic and cardiac defects. Transgenic Res 2010; 19(6): 1069–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Jaffe M, Sesti C, Washington IM, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling in myogenic cells regulates vascular morphogenesis, differentiation, and matrix synthesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2012; 32(1): e1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Carvalho RL, Itoh F, Goumans MJ, et al. Compensatory signalling induced in the yolk sac vasculature by deletion of TGFbeta receptors in mice. J Cell Sci 2007; 120(Pt 24): 4269–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Hu JH, Wei H, Jaffe M, et al. Postnatal deletion of the type II transforming growth factor-beta receptor in smooth muscle cells causes severe aortopathy in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2015; 35(12): 2647–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Li W, Li Q, Jiao Y, et al. Tgfbr2 disruption in postnatal smooth muscle impairs aortic wall homeostasis. J Clin Invest 2014; 124(2): 755–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Zhang P, Hou S, Chen J, et al. Smad4 deficiency in smooth muscle cells initiates the formation of aortic aneurysm. Circ Res 2016; 118(3): 388–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Judge DP, Biery NJ, Keene DR, et al. Evidence for a critical contribution of haploinsufficiency in the complex pathogenesis of Marfan syndrome. J Clin Invest 2004; 114(2): 172–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Habashi JP, Judge DP, Holm TM, et al. Losartan, an AT1 antagonist, prevents aortic aneurysm in a mouse model of Marfan syndrome. Science 2006; 312(5770): 117–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Neptune ER, Frischmeyer PA, Arking DE, et al. Dysregulation of TGF-beta activation contributes to pathogenesis in Marfan syndrome. Nat Genet 2003; 33(3): 407–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Gallo EM, Loch DC, Habashi JP, et al. Angiotensin II-dependent TGF-beta signaling contributes to Loeys-Dietz syndrome vascular pathogenesis. J Clin Invest 2014; 124(1): 448–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Holm TM, Habashi JP, Doyle JJ, et al. Noncanonical TGFbeta signaling contributes to aortic aneurysm progression in Marfan syndrome mice. Science 2011; 332(6027): 358–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Cook JR, Clayton NP, Carta L, et al. Dimorphic effects of transforming growth factor-beta signaling during aortic aneurysm progression in mice suggest a combinatorial therapy for Marfan syndrome. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2015; 35(4): 911–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Lacro RV, Dietz HC, Sleeper LA, et al. Atenolol versus losartan in children and young adults with Marfan’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 2014; 371(22): 2061–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Mallat Z, Daugherty A. AT1 receptor antagonism to reduce aortic expansion in Marfan syndrome: lost in translation or in need of different interpretation? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2015; 35(2): e10–e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Cao C, Lawrence DA, Li Y, et al. Endocytic receptor LRP together with tPA and PAI-1 coordinates Mac-1-dependent macrophage migration. EMBO J 2006; 25(9): 1860–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Mantuano E, Brifault C, Lam MS, et al. LDL receptor-related protein-1 regulates NFkappaB and microRNA-155 in macrophages to control the inflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016; 113(5): 1369–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Urmoneit B, Prikulis I, Wihl G, et al. Cerebrovascular smooth muscle cells internalize Alzheimer amyloid beta protein via a lipoprotein pathway: implications for cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Lab Invest 1997; 77(2): 157–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Bell RD, Deane R, Chow N, et al. SRF and myocardin regulate LRP-mediated amyloid-beta clearance in brain vascular cells. Nat Cell Biol 2009; 11(2): 143–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Kanekiyo T, Cirrito JR, Liu CC, et al. Neuronal clearance of amyloid-beta by endocytic receptor LRP1. J Neurosci 2013; 33(49): 19276–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Davis FM, Rateri DL, Balakrishnan A, et al. Smooth muscle cell deletion of low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 augments angiotensin II-induced superior mesenteric arterial and ascending aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2015; 35(1):155–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Zhou L, Takayama Y, Boucher P, Tallquist MD, Herz J. LRP1 regulates architecture of the vascular wall by controlling PDGFRbeta-dependent phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation. PloS One 2009; 4(9): e6922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Yang CY, Chanalaris A, Troeberg L. ADAMTS and ADAM metalloproteinases in osteoarthritis - looking beyond the ‘usual suspects’. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017. July; 25(7):1000–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Verma P, Dalal K. ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5: key enzymes in osteoarthritis. J Cell Biochem 2011; 112(12): 3507–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Troeberg L, Nagase H. Proteases involved in cartilage matrix degradation in osteoarthritis. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012; 1824(1): 133–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Yabluchanskiy A, Ma Y, Iyer RP, Hall ME, Lindsey ML. Matrix metalloproteinase-9: Many shades of function in cardiovascular disease. Physiology (Bethesda ) 2013; 28(6): 391–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Longo GM, Xiong W, Greiner TC, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 work in concert to produce aortic aneurysms. J Clin Invest 2002; 110(5): 625–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Li YH, Li XM, Lu MS, Lv MF, Jin X. The expression of the BRM and MMP2 genes in thoracic aortic aneurysm and aortic dissection. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2017; 21(11): 2743–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Meffert P, Tscheuschler A, Beyersdorf F, et al. Characterization of serum matrix metalloproteinase 2/9 levels in patients with ascending aortic aneurysms. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2017; 24(1): 20–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Yang Z, Strickland DK, Bornstein P. Extracellular MMP2 levels are regulated by the LRP scavenger receptor and thrombospondin 2. J Biol Chem 2000; 276(11): 8403–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Clausen T, Kaiser M, Huber R, Ehrmann M. HTRA proteases: regulated proteolysis in protein quality control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2011; 12(3): 152–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Ohlsson K, Ganrot PO, Laurell CB. In vivo interaction beween trypsin and some plasma proteins in relation to tolerance to intravenous infusion of trypsin in dog. Acta Chir Scand 1971; 137(2): 113–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Gettins PG, Dolmer K. The High Affinity Binding Site on Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) for the Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor-related Protein (LRP1) Is Composed of Four Basic Residues. J Biol Chem 2016; 291(2): 800–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Makarova A, Mikhailenko I, Bugge TH, et al. The low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein modulates protease activity in the brain by mediating the cellular internalization of both neuroserpin and neuroserpin-tissue-type plasminogen activator complexes. J Biol Chem 2003; 278(50): 50250–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Scilabra SD, Yamamoto K, Pigoni M, et al. Dissecting the interaction between tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3 (TIMP-3) and low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 (LRP-1): Development of a “TRAP” to increase levels of TIMP-3 in the tissue. Matrix Biol 2017; 59: 69–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Loukinova E, Ranganathan S, Kuznetsov S, et al. PDGF-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of the LDL receptor-related protein (LRP): Evidence for integrated co-receptor function between LRP and the PDGF receptor. J Biol Chem 2002; 277(18): 15499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Muratoglu SC, Mikhailenko I, Newton C, Migliorini M, Strickland DK. Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) forms a signaling complex with platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta in endosomes and regulates activation of the MAPK pathway. J Biol Chem 2010; 285(19): 14308–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Huang SS, O’Grady P, Huang JS. Human Transforming Growth Factor beta alpha2-Macroglobulin Complex Is a Latent Form of Transforming Growth Factor beta. J Biol Chem 1988; 263: 1535–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Huang SS, Leal SM, Chen CL, Liu IH, Huang JS. Identification of insulin receptor substrate proteins as key molecules for the TbetaR-V/LRP-1-mediated growth inhibitory signaling cascade in epithelial and myeloid cells. FASEB J 2004; 18(14): 1719–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Mantuano E, Inoue G, Li X, et al. The hemopexin domain of matrix metalloproteinase-9 activates cell signaling and promotes migration of schwann cells by binding to low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J Neurosci 2008; 28(45): 11571–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Mantuano E, Lam MS, Gonias SL. LRP1 assembles unique co-receptor systems to initiate cell signaling in response to tissue-type plasminogen activator and myelin-associated glycoprotein. J Biol Chem 2013; 288(47): 34009–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Shi Y, Mantuano E, Inoue G, Campana WM, Gonias SL. Ligand binding to LRP1 transactivates Trk receptors by a Src family kinase-dependent pathway. Sci Signal 2009; 2(68): ra18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Lockyer P, Mao H, Fan Q, et al. LRP1-Dependent BMPER Signaling Regulates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Vascular Inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017; 37(8): 1524–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Stiles TL, Dickendesher TL, Gaultier A, et al. LDL receptor-related protein-1 is a sialic-acid-independent receptor for myelin-associated glycoprotein that functions in neurite outgrowth inhibition by MAG and CNS myelin. J Cell Sci 2013; 126(Pt 1): 209–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Herz J, Goldstein JL, Strickland DK, Ho YK, Brown MS. 39-kDa protein modulates binding of ligands to low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein/α2-macroglobulin receptor. J Biol Chem 1991; 266: 21232–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Williams SE, Ashcom JD, Argraves WS, Strickland DK. A novel mechanism for controlling the activity of α2-macroglobulin receptor/low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. Multiple regulatory sites for 39-kDa receptor-associated protein. J Biol Chem 1992; 267: 9035–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Bu G, Rennke S. Receptor-associated protein is a folding chaper-one for low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J Biol Chem 1996; 271: 22218–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Stefansson S, Lawrence DA. The serpin PAI-1 inhibits cell migration by blocking integrin alpha V beta 3 binding to vitronectin [see comments]. Nature 1996; 383: 441–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Degryse B, Neels JG, Czekay RP, et al. The low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein is a motogenic receptor for plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. J Biol Chem 2004; 279(21): 22595–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Geetha N, Mihaly J, Stockenhuber A, et al. Signal integration and coincidence detection in the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) cascade: concomitant activation of receptor tyrosine kinases and of LRP-1 leads to sustained ERK phosphorylation via down-regulation of dual specificity phosphatases (DUSP1 and −6). J Biol Chem 2011; 286(29):25663–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- [100].Kozlova N, Jensen JK, Chi TF, Samoylenko A, Kietzmann T. PAI-1 modulates cell migration in a LRP1-dependent manner via beta-catenin and ERK1/2. Thromb Haemost 2015; 113(5):988–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Huang SS, Ling TY, Tseng WF, et al. Cellular growth inhibition by IGFBP-3 and TGF-{beta}1 requires LRP-1. The FASEB Journal 2003; 17(14):2068–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Tseng WF, Huang SS, Huang JS. LRP-1/TbetaR-V mediates TGF-beta1-induced growth inhibition in CHO cells. FEBS Lett 2004; 562(1–3):71–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Brandan E, Retamal C, Cabello-Verrugio C, Marzolo MP. The low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein functions as an endocytic receptor for decorin. J Biol Chem 2006; 281(42): 31562–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Cabello-Verrugio C, Santander C, Cofre C, et al. The internal region leucine-rich repeat 6 of decorin interacts with low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1, modulates transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta-dependent signaling, and inhibits TGF-beta-dependent fibrotic response in skeletal muscles. J Biol Chem 2012; 287(9): 6773–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Riquelme C, Larrain J, Schonherr E, et al. Antisense inhibition of decorin expression in myoblasts decreases cell responsiveness to transforming growth factor beta and accelerates skeletal muscle differentiation. J Biol Chem 2001; 276(5): 3589–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Cabello-Verrugio C, Brandan E. A novel modulatory mechanism of transforming growth factor-beta signaling through decorin and LRP-1. J Biol Chem 2007; 282(26): 18842–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Nakajima C, Kulik A, Frotscher M, et al. Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) modulates N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-dependent intracellular signaling and NMDA-induced regulation of postsynaptic protein complexes. J Biol Chem 2013; 288(30):21909–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Newton CS, Loukinova E, Mikhailenko I, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta (PDGFR-beta) activation promotes its association with the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP). Evidence for co-receptor function. J Biol Chem 2005. July; 280(30): 27872–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Barnes H, Larsen B, Tyers M, van Der GP. Tyrosine phosphorylated LDL receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) associates with the adaptor protein Shc in Src-transformed cells. J Biol Chem 2001; 22: 19119–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Craig J, Mikhailenko I, Noyes N, Migliorini M, Strickland DK. The LDL Receptor-Related Protein 1 (LRP1) Regulates the PDGF Signaling Pathway by Binding the Protein Phosphatase SHP-2 and Modulating SHP-2-Mediated PDGF Signaling Events. PLoS One 2013; 8(7): e70432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Yamauchi K, Yamauchi T, Mantuano E, et al. Low-density lipo-protein receptor related protein-1 (LRP1)-dependent cell signaling promotes neurotrophic activity in embryonic sensory neurons. PLoS One 2013; 8(9): e75497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Zilberberg A, Yaniv A, Gazit A. The low density lipoprotein receptor-1, LRP1, interacts with the human frizzled-1 (HFz1) and down-regulates the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 2004; 279(17): 17535–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Ponticos M Connective tissue growth factor (CCN2) in blood vessels. Vascul Pharmacol. 2013. March; 58(3):189–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Segarini PR, Nesbitt JE, Li D, et al. The Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor-related Protein/alpha 2-Macroglobulin Receptor Is a Receptor for Connective Tissue Growth Factor. J Biol Chem 2001; 276(44): 40659–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Yang M, Huang H, Li J, Li D, Wang H. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the LDL receptor-related protein (LRP) and activation of the ERK pathway are required for connective tissue growth factor to potentiate myofibroblast differentiation. FASEB J 2004; 18(15): 1920–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Yamamoto K, Owen K, Parker AE, et al. Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1)-mediated endocytic clearance of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs-4 (ADAMTS-4): functional differences of non-catalytic domains of ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5 in LRP1 binding. J Biol Chem. 2014; 289(10): 6462–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Yamamoto K, Troeberg L, Scilabra SD, et al. LRP-1-mediated endocytosis regulates extracellular activity of ADAMTS-5 in articular cartilage. FASEB J 2013; 27(2): 511–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Yamamoto K, Okano H, Miyagawa W, et al. MMP-13 is constitutively produced in human chondrocytes and co-endocytosed with ADAMTS-5 and TIMP-3 by the endocytic receptor LRP1. Matrix Biol 2016; 56:57–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Hahn-Dantona E, Ruiz JF, Bornstein P, Strickland DK. The Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor-related Protein Modulates Levels of Matrix Metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) by Mediating Its Cellular Ca-tabolism. J Biol Chem 2001; 276(18): 15498–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Rohlena J, Kolkman JA, Boertjes RC, Mertens K, Lenting PJ. Residues Phe342-Asn346 of activated coagulation factor IX contribute to the interaction with low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J Biol Chem 2003; 278(11): 9394–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Saenko EL, Yakhyaev AV, Mikhailenko I, Strickland DK, Sarafanov AG. Role of the low density lipoprotein-related protein receptor in mediation of factor VIII catabolism. J Biol Chem 1999; 274(53): 37685–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Lenting PJ, Neels JG, van Den Berg BM, et al. The light chain of factor VIII comprises a binding site for low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J Biol Chem 1999; 274(34):23734–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Bouchard BA, Meisler NT, Nesheim ME, et al. A unique function for LRP-1: a component of a two-receptor system mediating specific endocytosis of plasma-derived factor V by megakaryocytes. J Thromb Haemost 2008; 6(4): 638–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Bu G, Williams S, Strickland DK, Schwartz AL. Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein/α2-macroglobulin receptor is an hepatic receptor for tissue-type plasminogen activator. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1992; 89: 7427–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Kounnas MZ, Henkin J, Argraves WS, Strickland DK. Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein/α2-macroglobulin receptor mediates cellular uptake of pro-urokinase. J Biol Chem 1993; 268: 21862–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Kounnas MZ, Church FC, Argraves WS, Strickland DK. Cellular internalization and degradation of antithrombin III-thrombin, heparin cofactor II-thrombin, and α1-antitrypsin-trypsin complexes is mediated by the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J Biol Chem 1996; 271: 6523–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Kasza A, Petersen HH, Heegaard CW, et al. Specificity of serine proteinase/serpin complex binding to very-low-density lipoprotein receptor and alpha2-macroglobulin receptor/low-density-lipoprotein-receptor-related protein. Eur J Biochem 1997; 248: 270–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Warshawsky I, Broze GJJ, Schwartz AL. The low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein mediates the cellular degradation of tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994; 91(14): 6664–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Knauer MF, Kridel SJ, Hawley SB, Knauer DJ. The efficient catabolism of thrombin-protease nexin 1 complexes is a synergistic mechanism that requires both the LDL receptor-related protein and cell surface heparins. J Biol Chem 1997; 272: 29039–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Nykjær A, Petersen CM, Moller B, et al. Purified α2-macroglobulin receptor/LDLreceptor-relatedproteinbindsurokinase •plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 complex. Evidence that the α2-macroglobulin receptor mediates cellular degradation of urokinase receptor-bound complexes. J Biol Chem 1992; 267: 14543–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Makarova A, Mikhailenko I, Bugge TH, et al. The LDL receptor-related protein modulates protease activity in the brain by mediating the cellular internalization of both neuroserpin and neuroserpin: tPA complexes. J Biol Chem 2003; M309150200. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [132].Chiabrando GA, Vides MA, Sanchez MC. Differential binding properties of human pregnancy zone protein- and alpha2-macroglobulin-proteinase complexes to low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. Arch Biochem Biophys 2002; 398(1): 73–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [133].Storm D, Herz J, Trinder P, Loos M. C1 inhibitor-C1s complexes are internalized and degraded by the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J Biol Chem 1997; 272: 31043–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Scilabra SD, Troeberg L, Yamamoto K, et al. Differential regulation of extracellular tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3 levels by cell membrane-bound and shed low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1. J Biol Chem 2013; 288(1): 332–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]