Abstract

Disparities in health outcomes for heart, lung, blood and sleep-related health conditions are pervasive in the United States, with an unequal burden experienced among structurally disadvantaged populations. One reason for this disparity is that despite the existence of effective interventions that promote health equity, few have been translated and implemented consistently in the health care system. To achieve health equity, there is a dire need to implement and disseminate effective evidence-based interventions that account for the complex and multi-layered social determinants of health among marginalized groups across healthcare settings. To that end, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Center for Translation Research and Implementation Science invited early stage investigators to participate in the inaugural Saunders-Watkins Leadership Workshop in May of 2018 at the National Institutes of Health. The goals of the workshop were to: (1) present an overview of health equity research, including areas which require ongoing investigation; (2) review how the fields of health equity and implementation science are related; (3) demonstrate how implementation science could be utilized to advance health equity; and (4) foster early-stage investigator career success in Heart, Lung, Blood and Sleep-related research. Herein, we highlight key themes from the two-day workshop and offer recommendations for the future direction of health equity and implementation science research in the context of heart, lung, blood and sleep-related health conditions.

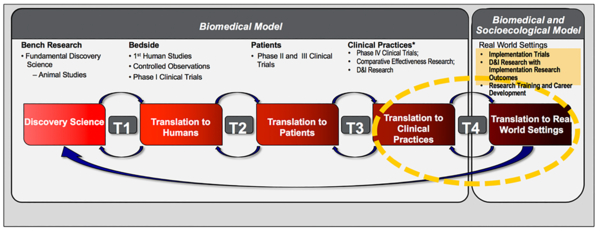

Although progress has been made to identify the drivers of health disparities across heart, lung, blood, and sleep (HLBS) conditions, an unequal disease burden remains.1–3 One cause for persistent disparities is a lack of translational and implementation research, to translate the existing knowledge base into action through the distribution and integration of effective interventions to specific audiences and contexts (Figure 1).4, 5 Addressing this gap requires developing, fostering, and sustaining a community of investigators dedicated to health equity and implementation science research.6

Figure 1. Continuum of Clinical and Translational Research.

The 4 steps involved in the translation of fundamental discovery science into clinical and public health impact in real-world settings. T1, the first translational step—bench to bedside or animal studies to humans; T2, the second translational step—translating science discovery to patients with specific diseases; T3, the third translational step—translating clinical insights to service delivery in clinical practices; T4, the fourth translational step—translating effective interventions to real-world settings. Reproduced from Mensah, GA. A new global heart series-perspectives from the NHLBI. Glob Heart. 2013;8:283–284.

To that end, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s (NHLBI) Center for Translation Research and Implementation Science (CTRIS) hosted the first Saunders-Watkins Leadership Workshop (SWLW), honoring Dr. Elijah Saunders and Dr. Levi Watkins, Jr., two prominent African American cardiovascular specialists who dedicated their professional lives to minimizing inequities in health and mentoring the next generation of research scientists.7–9 Held on May 22 to 23, 2018 at the National Institute of Health (NIH), the goals of the SWLW were to: (1) present an overview of health equity research, including scientific gains to date and areas which require ongoing investigation; (2) review how the fields of health equity and implementation science are related; (3) demonstrate how implementation science could be utilized to advance health equity; and (4) foster early-stage investigator career success in HLBS -related research that pertains to health equity and implementation science.10 Programming included keynote addresses from leaders in the field, who represented the NIH Office of the Director, NHLBI, CTRIS, the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD), the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the U.S. Department of Army, and the Federal Communications Commission. Health equity and implementation science researchers presented on core topics and facilitated skill-building sessions. Fifty junior faculty and postdoctoral fellows from across the United States conducting research in these areas were invited to attend including co-authors (MRS, SEE, YCM, JYB); the SWLW was chaired by one co-author (MNS). Oral and poster presentations, as well as opportunities for professional development among the participants, were integrated throughout the workshop.

Health Equity Research in HLBS Conditions: A Call to Action

Although age-standardized CVD mortality rates have declined substantially in the US over the last 40 years,11–13 CVD still accounts for 800,000 deaths each year. Moreover, CVD morbidity and mortality are unequally distributed in the population, with disparities persisting by sex, race/ethnicity, and geographic region.3 Evidence suggests this may be in part due to suboptimal control of both biologic and behavioral risk factors among certain groups. As the population becomes increasingly diverse,14 increased attention to understanding and addressing these disparities among marginalized populations will be critical. Owing to this need, SWLW speakers identified areas that will require ongoing investigation in the coming years including: 1) rural health; 2) hypertension; 3) the opioid epidemic; and 4) precision medicine.

Rural Health Disparities

Disparities in morbidity and mortality among residents of rural areas in the United States are well documented.15, 16 Data from several large, nationally representative samples have demonstrated the prevalence of diabetes, coronary heart disease and obesity are higher in rural communities compared to urban communities.17, 18 Additionally, studies have shown physical activity rates and the consumption of fruits and vegetables are lower in rural populations, compared with urban and suburban counterparts.19, 20

While the majority of research on rural health disparities examines inequalities between rural and urban communities, recent data suggest important disparities exist within rural communities. A report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which used data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, found that disparities exist across racial/ethnic populations in rural communities in the US. For example, in rural areas, American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/ANs), blacks, and Hispanics were found to have more self-reported fair or poor health, compared to whites.21 In addition, mental distress was reported more often among AI/ANs and blacks compared to whites. All racial/ethnic minority populations were less likely than non-Hispanic whites to report having a personal health care provider in rural areas. These results suggest that while all rural populations experience health issues, the issues may differ by race/ethnicity.22 Community needs assessments are needed to better understand these differences and develop tailored, culturally appropriate initiatives to eliminate them. For example, health behavior models developed and tested among urban populations may fail to address important cultural and social differences associated with diverse identity groups living in rural communities. SWLW speakers explained that in order to have a more comprehensive understanding of risk factors for health in rural communities, future research needs to look past urban-rural comparisons, and also investigate differences within rural populations.

Disparities in Hypertension

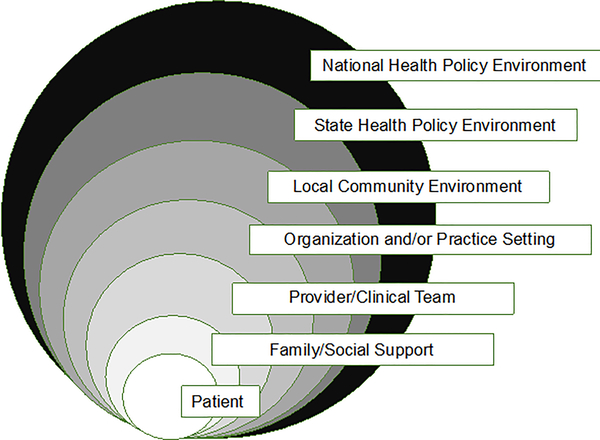

Racial disparities in hypertension and hypertension-related outcomes have been pervasive for decades, with African American individuals facing greater risks for adverse outcomes than European-American individuals.23, 24 Despite awareness of this disparities and efforts to address it with treatment, blood pressure control is worse among African Americans with hypertension compared to whites.25, 26 This is problematic since poor blood pressure control is associated with greater rates of stroke, end-stage renal disease, and congestive heart failure. Studies have shown that, compared with whites individuals, African-Americans receiving adequate treatment should achieve similar declines in overall blood pressure and experience lower rates of hypertension-related morbidity and mortality.27 Yet, this goal has not been achieved. Reasons for this are multifold. First, barriers to reducing disparities in blood pressure control exist at several levels beyond the patient (insurance, health literacy, English proficiency, discrimination, adherence to medications and lifestyle recommendations), including: the interpersonal level (family and social support systems), the provider level (communication skills, cultural responsiveness), organizational and practice setting (decision support, care coordination, patient education), and at the policy level (reimbursement) (Figure 2).28 Thus, it is likely multi-level interventions targeting different levels of influence will be most successful.29 An example of this can be seen in a recent study by Shahu et al (2019) which examined the association between household income and blood pressure control in the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack (ALLHAT) trial, the largest RCT of antihypertensive therapy in which participants had equal access to blood pressure medications.30 Authors found despite this and the rigorous randomization process, socio-economic context was significantly associated with blood pressure control. This study demonstrates providing access to hypertension treatment alone – that is, addressing one barrier to blood pressure control -- may be insufficient to overcome disparities.31 Second, interventions which can be promoted to patients and community-based organizations may improve uptake and effectiveness, as evident by recent successes of the Barbershop32 and FAITH trials,33 whereby participants were engaged in behavior change interventions in the community and via community members. Third, given the historic lack of representation across structurally disadvantaged groups, researchers ought to strive to include racial/ethnic minorities, individuals of low socioeconomic status, underserved rural residents, and sexual and gender identity minorities in their study samples,34 if they want to conduct the most rigorous and equitable science.

Figure 2. Factors Influencing Disparities in Hypertension Control by Levels of the Social Ecological Model.

Multiple barriers to blood pressure control exist, at the patient, interpersonal, clinical, organizational, local, state, and national level. Adapted from Mueller M, Purnell TS, Mensah GA, Cooper LA. Reducing racial and ethnic disparities in hypertension prevention and control: What will it take to translate research into practice and policy? American Journal of Hypertension. 2015;28:699–716.

Disparities in the Opioid Epidemic

Despite receiving national attention over the last few years, the opioid epidemic is worsening. The CDC reported mortality rate for drug overdoses increased from 16.3 per 100,000 people in 2015 to 19.8 per 100,000 in 2016.35 When stratified by race/ethnicity, the drug-related mortality rate (per 100,000) in 2016 was 25.3 among whites compared to 17.1 in blacks and 9.5 in Hispanics.36 These findings are in sharp contrast to prior epidemics, which disproportionately affected racial/ethnic minority groups. The reasons for why the current opioid epidemic is heavily concentrated among low-income White communities are not well understood and additional research is needed.

A recent study by Friedman et al. (2019) sought to determine if differential prescribing of opioids by race/ethnicity and income level could explain opioid overdoses among low-income White communities.37 Using 2011–2015 data from the California’s Controlled Substance Utilization Review and Evaluation System (CURES) database, which tracks all prescriptions for the Drug Enforcement Administration–scheduled medication in California,38 they found residents of neighborhoods with the highest proportion of white people were more than twice as likely to be prescribed an opioid for pain relief than residents of neighborhoods with fewer whites. Zip codes with the highest proportion of racial/ethnic minority residents saw the opposite. Overall, they found opioid overdose deaths were concentrated in lower-income, mostly white regions, with a 10-fold difference in overdose rates across the race/ethnicity–income gradient. The race/ethnicity and income pattern of opioid overdoses mirrored prescription rates, suggesting differential exposure to opioids via the health care system may have induced the large, observed racial/ethnic gradient in the opioid epidemic.

These findings emphasize the importance of monitoring regional prescribing trends and the need for tailored interventions that emphasize safe prescribing practices, as well as discussion of overdose risk and co-prescribing of naloxone.39 Additionally, the data suggests persistent disparities in treatment and access to pain medications, which requires ongoing investigation and attention. Importantly, this disparity is not new. Indeed, seminal research by Todd et al (1993) found that Hispanics were twice as likely as non-Hispanic whites to not receive pain medicine in the emergency department when presenting with isolated long-bone fractures.40

Precision Medicine: Opportunities and Challenges

As defined by the National Library of Medicine, precision medicine is “an emerging approach for disease treatment and prevention that takes into account individual variability in genes, environment, and lifestyle for each person.”41 As such, precision medicine offers clinicians tools to better understand the complex biological and environmental mechanisms underlying a patient’s health, disease, or condition, and enables the prediction of which treatments will be most appropriate for which people.42 Indeed in recent years, rapid growth of large-scale databases and computational methods for analyzing data have led to increased interest and opportunities for its use. However, despite benefits and growth, there is also potential for precision medicine to exacerbate health disparities since many structurally disadvantaged groups may be left out or be unable to afford treatments.43 In order to ensure the scientific advances of precision medicine are positively impactful to all populations, research must include diverse populations including racial/ethnic minorities, structurally disadvantaged population subgroups, those people living with differing levels of ability, rural residents, sexual and gender identity minorities, and members of all marginalized groups.44, 45 Additionally, it will be important for the focus on genetic contributions to health to not over-shadow the socio-demographic, behavioral, and environmental factors which influence health outcomes.46 Finally, researchers will need to avoid conflating social identity constructs with biology and biological determinism.

Health Equity and Implementation Science: An Important Partnership

Equity, as defined by the World Health Organization, is the absence of avoidable, unfair, or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically, or geographically.47 “Health equity” implies everyone should have a fair opportunity to attain their full health potential and that no one should be disadvantaged from achieving this potential. Implementation science is defined as the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice, thereby improving the quality and effectiveness of health services.48

Although sometimes conceptualized as two separate fields, the workshop emphasized the importance of partnerships between health equity and implementation science and the potential for each field to complement and catalyze each other. In the United States, the Healthy People 2020 plan aims for “a society in which all people live long, healthy lives,” and one of the stated goals is to “achieve health equity, eliminate disparities, and improve the health of all groups,” thereby extending prior national goals focused solely on reducing health disparities.45 The field of implementation science has the potential to contribute substantively to this mission since its frameworks, theories and methodological approaches to promote evidence-based practice could be used to improve the translation of evidence among vulnerable populations.48 Thus, both health equity and implementation scientists can work towards ensuring that all patients receive the highest quality health care supported by research evidence.49

To date, however, the marriage of these fields has not been fully actualized. While research in cardiovascular disease has made marked gains in terms of the detection and explanation of disparities, efforts to develop, implement, sustain and evaluate interventions to reduce these disparities have fallen short. Conversely, while implementation science has made significant gains with the development of frameworks, theories, strategies, and measures, major gaps remain in the application of this knowledge to decrease disparities and achieve health equity.49 A few reasons for this exist. First, many groups including racial/ethnic minorities, rural populations, sexual and gender identity minorities, and socio-economically disadvantaged persons, Aboriginal peoples, and persons with disabilities have not been adequately represented in clinical trials and implementation studies.50 Second, interventions and implementation strategies are not always developed with the health of disparity populations in mind.51 Third, many existing frameworks do not integrate principles of both fields. Without recognizing and addressing these shortcomings, many interventions fail to reach and improve care for everyone.

Implementation Science: A Vehicle to Advance Health Equity

To address these issues, speakers at the SWLW demonstrated how the field of Implementation Science could be leveraged to improve the uptake of evidence-based interventions among structurally disadvantaged populations, thereby advancing health equity. Three examples of ways to do this include the use of: 1) new frameworks; 2) study designs; and 3) multi-stakeholder approaches.

New Frameworks

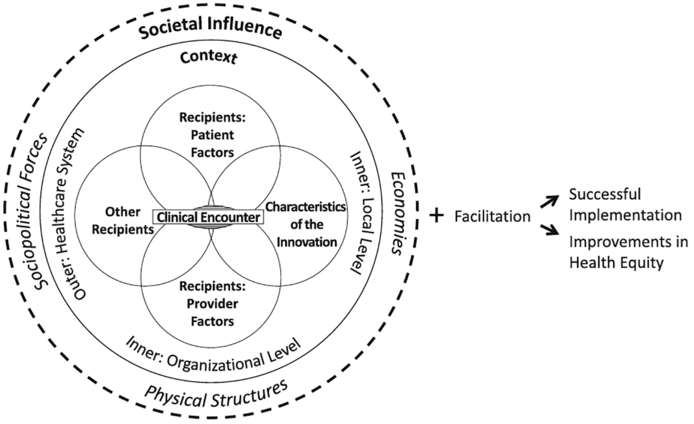

While frameworks have been used to guide health equity research (examples include: The NIMHD Research Framework,52 Social Ecological Model,53 Healthy People 2020,54 WHO’s Commission on the SDOH Conceptual Framework55) and implementation science research (examples include: Quality Implementation Framework, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research [CFIR]56, Reach, Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance [RE-AIM],57 and Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services [PARiSH]),58 few conceptual frameworks take both fields into account. Recently, however, two frameworks have been proposed to address this issue: 1) Equity-based framework for Implementation Research (EquIR) by Eslava-Schmalbach et al (2019)59 and 2) Health Equity Implementation Framework by Woodward et al (2019).60 Both frameworks build upon existing frameworks in Health Equity and Implementation Science, but also seek to integrate factors relevant to both fields. For example, the Health Equity Implementation Framework enables researchers to assess and address implementation problems that may contribute to healthcare inequities among vulnerable groups. As shown in Figure 3 the framework brings together well- known implementation science (Integrated-Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services [i-PARIHS])61 and health disparities frameworks (the Health Care Disparities Framework)62 to posit the innovation is delivered during a clinical encounter, but the clinical encounter itself has local and organizational contexts that need to be considered. Additionally, the model accounts for the healthcare system, the economy, sociopolitical forces, and physical structures, all of which are likely to influence uptake and outcomes.

Figure 3. The Health Equity Implementation Framework.

By bringing together well-known Implementation Science (Integrated-Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services [i-PARIHS]) and health disparities frameworks (the Health Care Disparities Framework), the Health Equity Implementation Framework demonstrates one way to modify an implementation framework to better assess health equity determinants. Reproduced from Woodward EN, Matthieu MM, Ucendu US, Rogal S, Kirchner JE. The health equity implementation framework: Proposal and preliminary study of hepatitis C virus treatment. Implement Sci. 2019;14:26.

Study Designs

Several presenters at the SWLW emphasized the importance of selecting appropriate study designs for optimal equity and implementation outcomes. For clinical trials, presenters discussed the benefits of using user-centered, factorial or stepped wedge designs, which allow researchers to address the multilayered nature of health beyond what traditional randomized control trials allow.56, 63 Additionally, using mixed-methods approaches, which involves collecting, analyzing, and interpreting quantitative and qualitative data that investigate the same phenomenon,64–66 were featured. As shown in Table 1, there are many ways to structure and analyze the components of mixed methods studies. Regardless of structure though, using a mixed methods approach not only allows investigators to deepen their understanding of the needs of complex populations, but also allows for earlier identification of potential successes and failures of various implementation strategies.67

Table 1.

Types of Mixed Methods Designs

| Element | Category | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | QUAL → quan | Sequential collection and analysis of quantitative and qualitative data, beginning with qualitative data, for primary purpose of exploration/hypothesis generation |

| qual → QUAN | Sequential collection and analysis of quantitative and qualitative data, beginning with qualitative data, for primary purpose of confirmation/hypothesis testing | |

| Quan → QUAL | Sequential collection and analysis of quantitative and qualitative data, beginning with quantitative data, for primary purpose of exploration/hypothesis generation | |

| QUAN → qual | Sequential collection and analysis of quantitative and qualitative data, beginning with quantitative data, for primary purpose of confirmation/hypothesis testing | |

| Qual + QUAN | Simultaneous collection and analysis of quantitative and qualitative data for primary purpose of confirmation/hypothesis testing | |

| QUAL + quan | Simultaneous collection and analysis of quantitative and qualitative data for primary purpose of exploration/hypothesis generation | |

| QUAN + QUAL | Simultaneous collection and analysis of quantitative and qualitative data, giving equal weight to both types of data | |

| Function | Convergence | Using both types of methods to answer the same question, either through comparison of results to see if they reach the same conclusion (triangulation) or by converting a data set from one type into another (e.g., quantifying qualitative data or qualifying quantitative data) |

| Complementarity | Using each set of methods to answer a related question or series of questions for purposes of evaluation (e.g., using quantitative data to evaluate outcomes and qualitative data to evaluate process) or elaboration (e.g., using qualitative data to provide depth of understanding and quantitative data to provide breadth of understanding) | |

| Expansion | Using one type of method to answer questions raised by the other type of method (e.g., using qualitative data set to explain results of analysis of quantitative data set) | |

| Development | Using one type of method to answer questions that will enable use of the other method to answer other questions (e.g., develop data collection measures, conceptual models or interventions) | |

| Sampling | Using one type of method to define or identify the participant sample for collection and analysis of data representing the other type of method (e.g., selecting interview informants based on responses to survey questionnaire) | |

| Process | Merge | Merge or converge the two datasets by actually bringing them together (e.g., convergence– triangulation to validate one dataset using another type of dataset) |

| Connect | Have one dataset build upon another data set (e.g., complementarity– elaboration, transformation, expansion, initiation or sampling) | |

| Embed | Conduct one study within another so that one type of data provides a supportive role to the other dataset (e.g., complementarity– evaluation: a qualitative study of implementation process embedded within an RCT of implementation outcome) |

Reproduced from Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Horwitz S, Chamberlain P, Hurlburt M, Landsverk J. Mixed method designs in Implementation Research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38:44.

Multi-stakeholder Approaches

Research that aims to improve health equity via implementation science will require that disparity populations (racial/ethnic minorities, low income communities, multi-lingual, persons with disabilities, etc) be included in a proportion that is representative of the degree of the health disparity.68 Additionally, building partnerships is critical. Much like health equity researchers who conduct community-based participatory research,69 implementation scientists often engage a variety of key stakeholders including patients, family members (caregivers), providers, practice directors, hospital leaders, and policy makers. Thus, in order to ensure that science is representative, recruitment of diverse populations and infrastructure to support multi-stakeholder collaborations are critical.

Existing and Emerging Opportunities for Training and Funding in Health Equity and Implementation Science Research

Given the persistent health disparities that exist in HLBS conditions, and the role implementation science can play towards reducing these disparities, training and funding for the next generation of health equity and implementation scientists are essential. In response to this need, CTRIS was established in 2014 with the goal of identifying and investing in evidence-based interventions, which when scaled, have the potential to improve population-level health and reduce health disparities in domestic and global settings.70 Directed by Dr. George Mensah, CRTIS aims to foster and support an integrated portfolio of late-stage T4 translational research, implementation science, and related training in HLBS disorders. As such, it sponsors programs like the SWLW, which in addition to lectures, offered numerous opportunities for career development for early stage investigators including skill-building sessions on scientific publishing, communicating effectively with NIH extramural program staff, and grant writing pertaining to health equity and implementation science. In addition to the SWLW, CRTIS has started an Implementation Research for Health Equity Webinar Series, which is designed to provide a platform to highlight topics about late-stage implementation research, health disparities, population health, biomedical research capacity building, and workforce diversity. Beyond the dissemination of knowledge, the goal of the webinar series is to bring researchers, doctors, nurses, pharmacists, trainees, and practitioners together to discuss novel research activities aimed at moving evidence-based HLBS interventions into practice. Finally, CTRIS has recently put forward several funding mechanisms to stimulate research at the intersection of these fields including: ‘Stimulating T4 Implementation Research to Optimize Integration of Proven-effective Interventions for Heart, Lung, and Blood Diseases and Sleep Disorders into Practice’ (STIMULATE) and ‘Disparities Elimination through Coordinated Interventions to Prevent and Control Heart and Lung Disease Risk’ (DECIPHeR).71, 72

In recognition of the gap between scientific knowledge and the implementation of that knowledge, the NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, in collaboration with the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the US Department of Veterans Affairs established the Training Institute for Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health (TIDIRH), designed to educate scientists and clinician scientists about conducting dissemination and implementation research.73 TIDIRH is comprised of a 5-month online course which culminates in a 2-day in-person training experience held at the NIH. In addition to preparing investigators to conduct implementation science research, TIDIRH also aims to cultivate interest for implementation science research at institutions around the country. As such, participants are expected to return to their home institutions and share what they have learned and engage local faculty.

Another notable program meant to stimulate skills and career development in health equity and implementation science is the Research in Implementation Science for Equity (RISE) Program hosted by University of California San Francisco’s Center for Vulnerable Populations.74 Part of the NHLBI’s Program to Increase Diversity among Individuals Engaged in Health-Related Research (NHLBI-PRIDE), RISE aims to train and sustain scholars underrepresented in biomedical sciences for long-term success in academic careers pursuing innovative research of interest to the NHLBI. The RISE program is comprised of a two-week summer institute, focused on implementation science and career mentoring, and a second summer institute the following summer, with sessions in between.

Several institutions across the country have also developed programming around these emerging areas of investigation. Examples include The Center for Dissemination and Implementation at Washington University in St. Louis and the Center for Research in Implementation Science and Prevention at the University of Colorado at Denver. Additionally, The Institute for Clinical and Translational Research at The University of Wisconsin-Madison started a Dissemination and Implementation Science Short Course. In 2018, the theme was, “A Vision for Health Equity: Applying a Health Equity Lens to Dissemination and Implementation Science.”75 The Short Course provided a forum for researchers and community stakeholders to explore the emerging field of dissemination and implementation science through the lens of health equity with national and local experts.

Finally, conferences and online resources have proliferated to meet the growing need of scholars in these areas. The Society for Implementation Research Collaboration created the Network of Expertise (NoE) to engage new and established investigators, evidence-based practice champions, and implementation practitioners through a both in-person and virtual Implementation Development Workshop.76 Additionally, each December, AcademyHealth holds the Science of Dissemination and Implementation in Health. This year’s theme, “Raising the bar on the rigor, relevance, and rapidity of dissemination and implementation science,” includes a track on Promoting Health Equity and Eliminating Disparities. Finally, several online toolkits, courses, and resources exist whereby scholars can obtain skills on study design, frameworks, and best-practices for publishing as they seek to conduct science in these areas.77

Conclusion

Despite progress in the identification of health disparities and the development of interventions to address them, implementing and sustaining interventions in HLBS conditions has been limited. To achieve health equity, evidence-based interventions must be translated, implemented, and disseminated to vulnerable populations. In May of 2018, NHLBI’s CTRIS convened the first SWLW to address this gap. The SWLW, which was geared toward junior faculty and postdoctoral fellows conducting HLBS research, reviewed the important partnership between health equity and implementation science and demonstrated how scientists can utilize implementation science methodologies and principles to advance health equity. Additionally, as the SWLW aimed to foster early-stage investigator career success among participants, existing and emerging opportunities for skill-building, career development, and funding in health equity and implementation science were reviewed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Melissa Green Parker, PhD, Program Official from the Center for Translation Research and Implementation Science (CTRIS) of the NHLBI for her role in organizing the SWLW and for her assistance with this manuscript. In addition, we would like to thank Helen Cox, MHS, (also from CTRIS) for her role in organizing the SWLW. Finally, we would like to extend our appreciation to all of the leadership and staff at CTRIS for making this workshop possible, as well as all of the speakers who offered their valuable insights.

Sources of Funding:

Dr. Sterling was supported by grant number T32HS000066 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality while attending the SWLW. She is currently supported, in part, by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or this foundation.

Dr. Commodore-Mensah was supported by a career development grant awarded to the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (5KL2TR001077–05)

Dr. Breland is supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service. Dr. Breland is a VA HSR&D Career Development awardee at the VA Palo Alto (15-257). Dr. Breland is also an investigator with the Implementation Research Institute (IRI), at the George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis; through an award from the National Institute of Mental Health (5R25MH08091607) and the Department of Veterans Affairs, HSR&D, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI). The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Dr. Nunez-Smith is supported, in part, by the NIH, NIMHD, NHLBI, NCI, NCATS, the Commonwealth Fund and the Doris Duke Charitable Fund. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIH or these foundations.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

None of the authors have any conflicts to report.

References

- 1.Sidney S, Quesenberry CP, Jaffe MG, Sorel M, Nguyen-Huynh MN, Kushi LH, Go AS and Rana JS. Recent trends in cardiovascular mortality in the United States and public health goals. JAMA cardiology. 2016;1:594–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roth GA, Johnson CO, Abate KH, Abd-Allah F, Ahmed M, Alam K, Alam T, Alvis-Guzman N, Ansari H and Ärnlöv J. The burden of cardiovascular diseases among US states, 1990–2016. JAMA cardiology. 2018;3:375–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Greenlund KJ and Croft JB. State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the United States. Circulation. 2005;111:1233–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mensah GA, Cooper RS, Siega-Riz AM, Cooper LA, Smith JD, Brown CH, Westfall JM, Ofili EO, Price LN and Arteaga S. Reducing cardiovascular disparities through community-engaged implementation research: a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop report. Circulation research. 2018;122:213–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engelgau MM, Narayan KV, Ezzati M, Salicrup LA, Belis D, Aron LY, Beaglehole R, Beaudet A, Briss PA and Chambers DA. Implementation Research to Address the United States Health Disadvantage: Report of a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Workshop. Global heart. 2018;13:65–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chambers DA, Proctor EK, Brownson RC and Straus SE. Mapping training needs for dissemination and implementation research: lessons from a synthesis of existing D&I research training programs. Translational behavioral medicine. 2016;7:593–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egan BM. Elijah Saunders in Memoriam. J Clin Hypertens. 17:415–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watkins L and Cornwell EE III. Department of Surgery, The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions. Archives of Surgery. 2003;138:239–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDaniels AK, Burris J, Cox E and Wood P. Levi Watkins, pioneer in cardiac surgery, dies. The Baltimore Sun; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plaisime M, Cox H and Parker MG. First Saunders-Watkins Workshop Focuses on Early-Stage Investigators NIH Record. Revised 2018. https://nihrecord.nih.gov/2018/09/21/first-saunders-watkins-workshop-focuses-early-stage-investigators. Accessed December 7, 2018.

- 11.Anderson KM. How Far Have We Come in Reducing Health Disparities?: Progress Since 2000: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Makuc DM, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, Moy CS, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Soliman EZ, Sorlie PD, Sotoodehnia N, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D and Turner MB. Heart disease and stroke statistics−-2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2–e220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lackland DT, Roccella EJ, Deutsch AF, Fornage M, George MG, Howard G, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Schwamm LH, Smith EE and Towfighi A. Factors influencing the decline in stroke mortality: a statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:315–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colby SL and Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. Population Estimates and Projections. Current Population Reports. P25–1143. US Census Bureau. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cosby AG, McDoom-Echebiri MM, James W, Khandekar H, Brown W and Hanna HL. Growth and Persistence of Place-Based Mortality in the United States: The Rural Mortality Penalty. American Journal of Public Health. 2018; 109:155–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh GK and Siahpush M. Widening rural-urban disparities in all-cause mortality and mortality from major causes of death in the USA, 1969–2009. Journal of urban health : bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2014;91:272–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Connor A and Wellenius G. Rural-urban disparities in the prevalence of diabetes and coronary heart disease. Public Health. 2012;126:813–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Befort CA, Nazir N and Perri MG. Prevalence of obesity among adults from rural and urban areas of the United States: findings from NHANES (2005–2008). The Journal of rural health : official journal of the American Rural Health Association and the National Rural Health Care Association. 2012;28:392–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michimi A and Wimberly MC. Associations of supermarket accessibility with obesity and fruit and vegetable consumption in the conterminous United States. Int J Health Geogr. 2010;9:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen SA, Greaney ML and Sabik NJ. Assessment of dietary patterns, physical activity and obesity from a national survey: Rural-urban health disparities in older adults. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0208268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.James CV, Moonesinghe R, Wilson-Frederick SM, Hall JE, Penman-Aguilar A and Bouye K. Racial/ethnic health disparities among rural adults—United States, 2012–2015. J MMWR Surveillance Summaries. 2017;66:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liao Y, Bang D, Cosgrove S, Dulin R, Harris Z, Taylor A, White S, Yatabe G, Liburd L and Giles W. Surveillance of health status in minority communities - Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health Across the U.S. (REACH U.S.) Risk Factor Survey, United States, 2009. Morbidity and mortality weekly report Surveillance summaries (Washington, DC : 2002). 2011;60:1–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howard G, Prineas R, Moy C, Cushman M, Kellum M, Temple E, Graham A and Howard V. Racial and geographic differences in awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension: the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke study. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2006;37:1171–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoon S, Fryar C and Carroll M. Hypertension prevalence and control among adults: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS data brief, no 220. 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howard G, Lackland DT, Kleindorfer DO, Kissela BM, Moy CS, Judd SE, Safford MM, Cushman M, Glasser SP and Howard VJ. Racial differences in the impact of elevated systolic blood pressure on stroke risk. JAMA internal medicine. 2013;173:46–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lackland DT. Racial Differences in Hypertension: Implications for High Blood Pressure Management. The American journal of the medical sciences. 2014;348:135–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ooi WL, Budner NS, Cohen H, Madhavan S and Alderman MH. Impact of race on treatment response and cardiovascular disease among hypertensives. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex : 1979). 1989;14:227–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mueller M, Purnell TS, Mensah GA and Cooper LA. Reducing racial and ethnic disparities in hypertension prevention and control: what will it take to translate research into practice and policy? American journal of hypertension. 2015;28:699–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clarke AR, Goddu AP, Nocon RS, Stock NW, Chyr LC, Akuoko JA and Chin MH. Thirty years of disparities intervention research: what are we doing to close racial and ethnic gaps in health care? Med Care. 2013;51:1020–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shahu A, Herrin J, Dhruva SS, Desai NR, Davis BR, Krumholz HM and Spatz ES. Disparities in Socioeconomic Context and Association With Blood Pressure Control and Cardiovascular Outcomes in ALLHAT. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2019;8:e012277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anstey DE, Christian J and Shimbo D. Income Inequality and Hypertension Control. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2019;8:e013636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Victor RG, Lynch K, Li N, Blyler C, Muhammad E, Handler J, Brettler J, Rashid M, Hsu B, Foxx-Drew D, Moy N, Reid AE and Elashoff RM. A Cluster-Randomized Trial of Blood-Pressure Reduction in Black Barbershops. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:1291–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schoenthaler AM, Lancaster KJ, Chaplin W, Butler M, Forsyth J and Ogedegbe G. Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial of FAITH (Faith-Based Approaches in the Treatment of Hypertension) in Blacks. Circulation Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2018;11:e004691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Institue on Minority Health and Health Disparities Fact Sheet. Revised 2019. https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/overview/. Accessed August 9, 2019.

- 35.Seth P, Scholl L, Rudd R and Bacon S. Overdose Deaths Involving Opioids, Cocaine, and Psychostimulants- United States, 2015–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:349–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.QuickStats: Age-Adjusted Death Rates for Drug Overdose, by Race/Ethnicity- National Vital Statistics System. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedman J, Kim D, Schneberk T, Bourgois P, Shin M, Celious A and Schriger DL. Assessment of Racial/Ethnic and Income Disparities in the Prescription of Opioids and Other Controlled Medications in California. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:469–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.State of California Department of Justice Office of the Attorney General. Controlled Substance Utilization Review and Evaluation System. Revised 2016. https://oag.ca.gov/cures. Accessed August 8, 2019.

- 39.Adams JM, Office of the Surgeon General UPHS, US Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC, Giroir BP and Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health UPHS, US Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC. Opioid Prescribing Trends and the Physician’s Role in Responding to the Public Health Crisis. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2019;179:476–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Todd KH, Samaroo N and Hoffman JR. Ethnicity as a risk factor for inadequate emergency department analgesia. Jama. 1993;269:1537–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.US National Library of Medicine. What is precision medicine? Revised 2015. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/primer/precisionmedicine/definition. Accessed August 9, 2019.

- 42.Lyles CR, Lunn MR, Obedin-Maliver J and Bibbins-Domingo K. The new era of precision population health: insights for the All of Us Research Program and beyond. Journal of translational medicine. 2018;16:211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meagher KM, McGowan ML, Settersten RA Jr, Fishman JR and Juengst ET. Precisely where are we going? Charting the new terrain of precision prevention. Annual review of genomics human genetics. 2017;18:369–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dankwa-Mullan I, Bull J and Sy F. Precision medicine and health disparities: Advancing the science of individualizing patient care. American journal of public health. 2015;105:S368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rajkomar A, Hardt M, Howell MD, Corrado G and Chin MH. Ensuring fairness in machine learning to advance health equity. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2018; 169:866–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adams SA and Petersen C. Precision medicine: opportunities, possibilities, and challenges for patients and providers. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA. 2016;23:787–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Health Organization. Health equity. Revised 2017. https://www.who.int/topics/health_equity/en/. Accessed August 1, 2019.

- 48.Eccles MP and Mittman BS. Welcome to implementation science. Implementation science. 2006; 1. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chinman M, Woodward EN, Curran GM and Hausmann LR. Harnessing Implementation Science to Increase the Impact of Health Disparity Research. Medical care. 2017;55:S16–S23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baumann AA, Cabassa LJ and Stirman SW. Adaptation in dissemination and implementation science. Dissemination implementation research in health: translating science to practice. 2017;2:286–300. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chinman M, Woodward EN, Curran GM and Hausmann LR. Harnessing Implementation Science to Increase the Impact of Health Disparity Research. Medical care. 2017;55:S16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.NIMHD Research Framework. NIH National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Revised 2017. https://nimhd.nih.gov/about/overview/research-framework/. Accessed December 5, 2018.

- 53.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A and Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health education quarterly. 1988;15:351–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy people 2020. Revised 2018. https://www.healthypeople.gov. Accessed February 7, 2019.

- 55.Solar O and Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. WHO. Revised 2010. https://www.who.int/social_determinants/publications/9789241500852/en/. Accessed November 16, 2018.

- 56.Mazzucca S, Tabak RG, Pilar M, Ramsey AT, Baumann AA, Kryzer E, Lewis EM, Padek M, Powell BJ and Brownson RC. Variation in Research Designs Used to Test the Effectiveness of Dissemination and Implementation Strategies: A Review. Frontiers in public health. 2018;6:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM and Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1322–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kitson AL, Rycroft-Malone J, Harvey G, McCormack B, Seers K and Titchen A. Evaluating the successful implementation of evidence into practice using the PARiHS framework: theoretical and practical challenges. Implementation science : IS. 2008;3:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eslava-Schmalbach J, Garzón-Orjuela N, Elias V, Reveiz L, Tran N and Langlois EV. Conceptual framework of equity-focused implementation research for health programs (EquIR). International journal for equity in health. 2019;18:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Woodward EN, Matthieu MM, Uchendu US, Rogal S and Kirchner JE. The health equity implementation framework: proposal and preliminary study of hepatitis C virus treatment. Implementation science : IS. 2019;14:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harvey G and Kitson A. PARIHS revisited: from heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of knowledge into practice. Implementation Science. 2016;11:1– [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, Crowley-Matoka M and Fine MJ. Advancing Health Disparities Research Within the Health Care System: A Conceptual Framework. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:2113–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lyon AR and Koerner K. User-Centered Design for Psychosocial Intervention Development and Implementation. Clinical psychology : a publication of the Division of Clinical Psychology of the American Psychological Association. 2016;23:180–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Curry LA, Krumholz HM, O’Cathain A, Plano Clark VL, Cherlin E and Bradley EH. Mixed methods in biomedical and health services research. Circulation Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2013;6:119–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leech NL and Onwuegbuzie AJ. A typology of mixed methods research designs. Quality & Quantity. 2009;43:265–275. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Curry L and Nunez-Smith M. Mixed methods in health sciences research: A practical primer: Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Horwitz S, Chamberlain P, Hurlburt M and Landsverk J. Mixed method designs in implementation research. Administration and policy in mental health. 2011;38:44–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McNulty M, Smith JD, Villamar J, Burnett-Zeigler I, Vermeer W, Benbow N, Gallo C, Wilensky U, Hjorth A, Mustanski B, Schneider J and Brown CH. Implementation Research Methodologies for Achieving Scientific Equity and Health Equity. Ethnicity & disease. 2019;29:83–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA and Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mensah GA, Engelgau M, Stoney C, Mishoe H, Kaufmann P, Freemer M and Fine L. News from NIH: a center for translation research and implementation science. J translational behavioral medicine. 2015;5:127–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.NOT-HL-19–715: Notice of Intent to Publish an NHLBI Funding Opportunity Announcement for STIMULATE-2 (R61/R33 Clinical Trial Required). Revised 2019. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-HL-19-715.html. Accessed August 9, 2019.

- 72.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Disparities Elimination through Coordinated Interventions to Prevent and Control Heart and Lung Disease Risk (DECIPHeR) (UG3/UH3 Clinical Trial Optional). Revised 2019. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/rfa-hl-20-003.html. Accessed August 9, 2019.

- 73.Meissner HI, Glasgow RE, Vinson CA, Chambers D, Brownson RC, Green LW, Ammerman AS, Weiner BJ and Mittman B. The U.S. training institute for dissemination and implementation research in health. Implementation science : IS. 2013;8:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.University of California San Francisco. Research in Implementation Science for Equity (RISE). Revised 2018. https://cvp.ucsf.edu/programs/capacity-building-training/research-implementation-science-equity-rise. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- 75.University of Wisconsin-Madison. A Vision for Health Equity: Applying a Health Equity Lens to Dissemination and Implementation Science. Revised 2018. https://ictr.wisc.edu/dni-short-course-2018/. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- 76.Society for Implementation Research Collaboration. Network of Expertise. Revised 2019. https://societyforimplementationresearchcollaboration.org/network-of-expertise/. Accessed August 13, 2019.

- 77.Ford B, Rabin B, Morrato EH and Glasgow RE. Online Resources for Dissemination and Implementation Science: Meeting Demand and Lessons Learned. J Clin Transl Sci. 2018;2:259– [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.