Abstract

Background:

The surgical approach to gallbladder cancer (GBCA) has evolved in recent years, but the impact on outcomes is unknown. This study describes differences in presentation, surgery, chemotherapy strategy, and survival for patients with GBCA over two decades at a tertiary referral center.

Methods:

A single-institution database was queried for patients with GBCA who underwent surgical evaluation and exploration and was studied retrospectively. Univariate logistic regression was used to assess the relationship between time and treatment. Univariate Cox proportional hazard regression assessed the association between year of diagnosis and survival.

Results:

From 1992–2015, 675 patients with GBCA were evaluated and 437 underwent exploration. Complete resection rates increased over time (p<0.001). In those submitted to complete resection (n=255, 58.4%), more recent years were associated with lower likelihood of bile duct resection and major hepatectomy but greater odds of neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy (p<0.05). No significant association was found between year of diagnosis and OS or RFS (p>0.05) for patients with complete resection.

Conclusion:

Over the study period, GBCA treatment evolved to include fewer biliary and major hepatic resections with no apparent adverse impact on outcome. Further prospective trials, specifically limited to GBCA, are needed to determine the impact of adjuvant chemotherapy.

Keywords: Gallbladder cancer, GBCA, Time trends, Survival

Introduction

Gallbladder cancer (GBCA) is the most common malignancy of the biliary tract. GBCA may be diagnosed incidentally following cholecystectomy for presumed benign biliary disease or when symptoms prompt imaging of the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Most patients present with locally advanced or metastatic disease, and complete resection can only be achieved in a subset of patients with localized tumors.(1–4) Even with resection, the risk of GBCA recurrence is high and is associated with the depth of tumor invasion, presence of residual disease, lymph node status, and jaundice at presentation.(2, 5–7) The clinical challenge in GBCA is selecting patients likely to benefit from surgery.

Over the last two decades, the surgical approach and medical management of patients with GBCA has evolved to address this challenge, but the impact of these developments on overall outcomes in a large surgical series is unknown. With regard to surgical therapy, clinical experience has confirmed that patients who present with jaundice are unlikely to undergo definitive surgery.(7) Less extensive resections are now favored and practice patterns have also shifted away from routine bile duct or port site resection.(8, 9) Furthermore, improvements in imaging technology have limited exploration in patients with disseminated disease, and those with evidence of locally advanced GBCA have even been increasingly offered preoperative treatment as a means of observing disease biology prior to attempted resection.(10–12)

Medical management has also changed during this time, but the increased utilization of both neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy has not been well-described in general clinical practice. Based on the ABC-02 trial that demonstrated improved overall survival (OS) with gemcitabine and cisplatin for unresectable biliary cancer, this combination became the recommended regimen for advanced biliary tract cancer.(13) However, the specific benefit of adjuvant therapy after complete resection of biliary cancer remained controversial. Now, in light of two recent randomized trials, including the PRODIGE 12-ACCORD 18 and BILCAP studies, the role of adjuvant chemotherapy for biliary cancer has been further elucidated.(14, 15) Therefore, in response to these many developments, a description of the temporal trends observed in the surgical management of GBCA is necessary to understand contemporary efforts to improve outcomes against this malignancy.

The aim of this retrospective study was to assess differences in presentation and management of surgical patients with GBCA over time and to analyze the impact of these changes on survival.

Methods

Patients

Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board for waiver of informed consent. All patients with GBCA evaluated by a hepatopancreatobiliary (HPB) surgeon at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) were recorded in a prospectively-maintained database containing demographic, pathology, operative and perioperative details, and initial recurrence and survival information. Follow up data was updated using the electronic medical record. All patients from 1992–2015 were included in the initial query. Patients that were seen in consultation only, or that underwent operation at another institution were excluded. Descriptive statistics were provided for all patients, including those that presented with inoperable metastatic disease. However, only patients that underwent surgery at MSKCC for adenocarcinoma, adenosquamous, or squamous carcinoma of the gallbladder were included in final analyses.

Surgical Approach

The authors’ surgical approach to GBCA has been described previously. (6, 8, 16) Laparoscopy was used selectively before laparotomy in patients with concern for metastatic disease. In cases without evidence of disseminated disease, laparotomy was performed. In recent years, selected patients had laparoscopic or robotic resections. A complete exploration of the abdomen was performed to assess the extent of disease. Ultrasonography of the liver was performed to assess for discontinuous liver metastases. Peritoneal metastases, discontinuous liver metastases, and involved N2 lymph nodes according to AJCC staging were generally considered unresectable disease.(17) Complete resection included curative-intent operations: segment 4 and 5 resection, hemihepatectomy, or extended hepatectomy in combination with portal lymphadenectomy.

Patients were classified as having primary or incidental GBCA based on previous history of cholecystectomy. In incidental GBCA, cholecystectomy was performed for presumed benign biliary disease and GBCA diagnosed on pathologic review of the specimen. For patients with incidental GBCA, residual disease (RD) at re-operation was recorded as distant or locoregional only. Distant RD included the liver, peritoneum, or abdominal wall. Locoregional only RD included the gallbladder fossa, bile duct, or lymph nodes.

Neoadjuvant and Adjuvant Chemotherapy

As a retrospective study, the type and duration of chemotherapy was not controlled but was determined by the primary medical oncologist during treatment. When available, chemotherapy information was recorded from the electronic medical record. As a tertiary referral center, patients often received chemotherapy treatment at a different institution. The number of cycles and specific toxicities were often unavailable and thus not included in analysis. For adjuvant chemotherapy, the date of initiation and the date of the last dose were recorded. Regimens were grouped according to gemcitabine only, combination gemcitabine and platinum, gemcitabine and other chemotherapy, 5-fluorouracil based regimen, or other.

Statistical Analyses

General

Patient characteristics were described using counts and percentages for categorical variables and medians and ranges for continuous variables. Kaplan Meier methods were used estimate median and annual survival and to illustrate survival trends. OS was calculated from the time of surgery until death. Patients alive at last follow-up were censored. RFS was calculated using date of surgery and recurrence or death. Patients alive and disease free at last follow-up were censored. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (The SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of OBservational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines were followed (Supplementary Material).(18)

Time Trends in Presentation and Management

Time was treated as a continuous variable and year was the unit of measurement. Univariate logistic regression was used to assess whether treatment and diagnostic information changed over time. Year of diagnosis was treated as a predictor variable. For all patients that underwent exploration, the association between year of diagnosis and complete resection status, lymph node status, primary or incidental diagnosis, jaundice at presentation and neoadjuvant chemotherapy were examined. For patients with complete resection, year of diagnosis was assessed for associations with adjuvant and neoadjuvant chemotherapy, bile duct resection, and major hepatic resection (hemihepatectomy and extended hepatectomy). These relationships were visualized with series plots.

Time Trends in Survival Outcomes and Associations between Disease Characteristics and Survival

Univariate Cox proportional hazard regression was used to assess the association between time and survival outcomes. In all patients that underwent exploration, univariate Cox proportional hazard regression was also used to assess the relationship between complete resection status, lymph node status, primary or incidental diagnosis, jaundice at presentation, and neoadjuvant chemotherapy with OS. In patients with a complete resection, this method was also used for lymph node status, primary or incidental diagnosis, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, jaundice at presentation, T-stage, margins, and adjuvant chemotherapy with both OS and RFS. To account for the time between surgery and adjuvant treatment, adjuvant chemotherapy was treated as a time dependent covariate. As Tis/T1a patients were infrequent in the surgical database and have distinct treatment recommendations, patients in this group (N=5) were excluded from the association between T-stage and survival outcomes.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Overall, 724 patients were evaluated by the HPB surgery service at MSKCC between 1992 and 2015. Patients seen in consultation only (n=32) or who had definitive resection at a different institution were excluded (n=17). The remaining 675 patients formed the descriptive sample. Demographics and disease characteristics are listed in Table 1 stratified by attempt at surgical resection. Among all patients, the median age was 67 years with a majority being female (63.7%). Most patients were white (75.9%) and approximately half were diagnosed with incidental GBCA (53.6%). In patients not subjected to exploration (n=220), the most common reasons were evidence of metastatic disease (n=123, 56%) and locally advanced disease (n=63, 29%).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics for Entire Cohort (N=675)

| Total | Surgery | No Surgery | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Gender | Male | 245 (36.3) | 168 (36.9) | 77 (35) |

| Female | 430 (63.7) | 287 (63.1) | 143 (65) | |

| Age at Diagnosis, years | Median (range) | 67.7 (28.1–92.5) | 67 (28.1–90.2) | 69.8 (29.1–92.5) |

| Race | White | 512 (75.9) | 365 (80.2) | 147 (66.8) |

| Black | 45 (6.7) | 28 (6.2) | 17 (7.7) | |

| Asian | 41 (6.1) | 29 (6.4) | 12 (5.5) | |

| Other | 6 (0.9) | 4 (0.9) | 2 (0.9) | |

| Unknown | 71 (10.5) | 29 (6.4) | 42 (19.1) | |

| Primary/Incidental | Incidental | 362 (53.6) | 276 (60.7) | 86 (39.1) |

| Primary | 313 (46.4) | 179 (39.3) | 134 (60.9) | |

| Histology | Adenocarcinoma | 596 (88.3) | 409 (89.9) | 187 (85) |

| Adenosquamous | 23 (3.4) | 21 (4.6) | 2 (0.9) | |

| Squamous | 8 (1.2) | 7 (1.5) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Neuroendocrine | 8 (1.2) | 8 (1.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 11 (1.6) | 6 (1.3) | 5 (2.3) | |

| Unknown | 29 (4.3) | 4 (0.9) | 25 (11.4) | |

| Complete Resection | Yes | 268 (39.7) | 268 (58.9) | 0 (0) |

| No | 187 (27.7) | 187 (41.1) | 0 (0) | |

| N/A | 220 (32.6) | 0 (0) | 220 (100) | |

| Reason for No Attempt at Surgical Resection | Distant Metastases | 101 (15) | 0 (0) | 101 (45.9) |

| Peritoneal Carcinomatosis | 22 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 22 (10) | |

| Locally Advanced | 63 (9.3) | 0 (0) | 63 (28.6) | |

| Comorbidities | 21 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 21 (9.5) | |

| Patient Refused | 7(1) | 0 (0) | 7 (3.2) | |

| Tis/T 1 a | 6 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 6 (2.7) | |

| N/A | 455 (67.4) | 455 (100) | 0 (0) | |

Numbers represent frequencies with percent in parentheses unless otherwise specified

The main cohort included 437 patients that underwent exploration. Table 2 reveals the operative details of these patients. Adenocarcinoma was the most frequent histology, present in 90% of patients (409/437) selected for surgery. Complete resection was achieved in 58% of patients (255/437). Among all patients with complete resection (n=255), final pathology revealed a positive margin in 15 patients.

Table 2.

Peri-operative Details for Patients That Underwent Exploration and Complete Resection

| All Surgical Patients (N=437) | ||

| Laparoscopy | Yes | 210 (48.1) |

| Laparotomy | Yes | 388 (88.8) |

| Stage | I | 20 (4.6) |

| II | 77 (17.6) | |

| III | 136 (31.1) | |

| IV | 170 (38.9) | |

| No Definitive Stage | 34 (7.8) | |

| Complete Resection | Yes | 255 (58.4) |

| Complete Resection Patients (N=255) | ||

| Surgical Procedure | Segment 4–5 Resection | 191 (74.9) |

| Extended Hepatectomy | 49 (19.2) | |

| Hemihepatectomy | 13 (5.1) | |

| Bile Duct Resection Only | 2 (0.8) | |

| Lymphadenectomy | Yes | 251 (98.4) |

| Concurrent Bile Duct Resection | Yes | 102 (40) |

| Extra Organ Resection | Yes | 26 (10.2) |

| Procedure Time (min) | Median (range) | 239 (88–584) |

| EBL (cc) | Median (range) | 300 (15–3000) |

| Incidental Patients (N=276) | ||

| RD on Pathology | Yes | 172 (62.3) |

| No | 104 (37.7) | |

| Location of Residual Disease | None | 104 (37.7) |

| Locoregional only | 92 (33.3) | |

| Distant | 80 (29) | |

Numbers represent frequencies with percent in parentheses unless otherwise specified

Time Trends in Presentation and Management for all Patients Undergoing Exploration

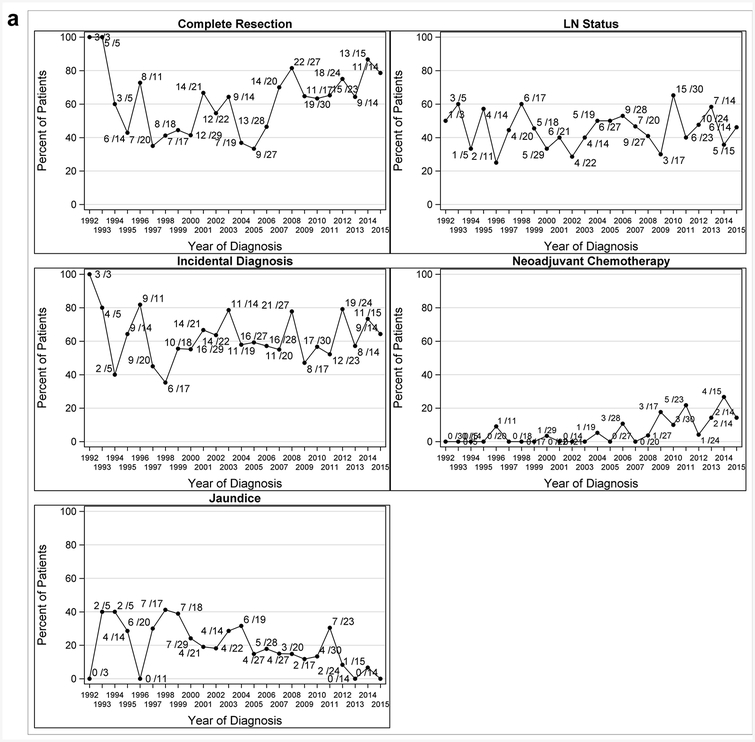

For all patients explored (n=437), later years of diagnosis were associated with higher odds of complete resection (OR 1.06, 95% CI: 1.02–1.09, p<0.001) and having received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (OR 1.20, 95% CI: 1.10–1.32, p<0.001), and lower odds of jaundice (OR 0.93, 95%CI: 0.89–0.97, p<0.001). However, year of diagnosis was not associated with positive lymph node status (OR: 1.01, 95% CI: 0.97–1.05, p=0.62) or presentation with incidental GBCA (OR: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.95–1.02, p=0.42). These findings align with the series plots in Figure 1a. Additionally, among patients with incidental GBCA, the likelihood of having residual disease at re-operation was lower in more recent years (OR 0.94, 95% CI: 0.90–0.98, p=0.005).

Figure 1a.

Series Plots for GBCA Presentation by Year for All Patients that Underwent Exploration 1992–2015 (N=437)

Time Trends in Surgical Therapy among Patients with Complete Resection

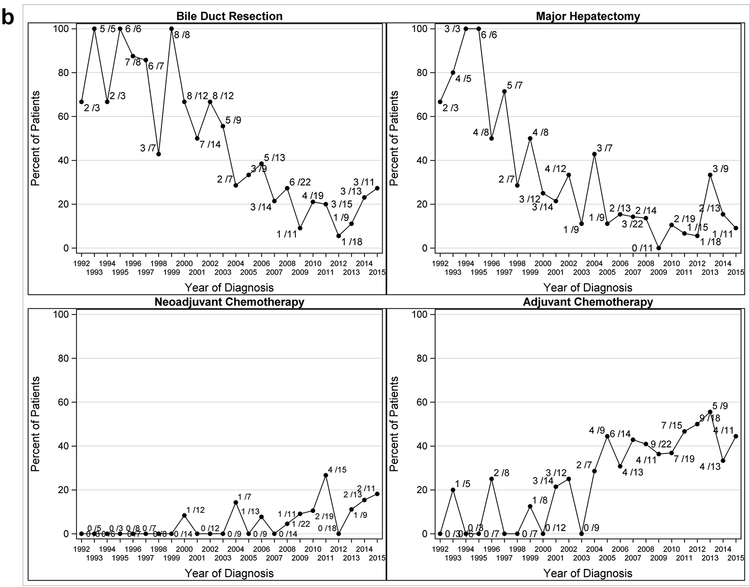

In patients with complete resection (n=255), the most frequent procedures were segment 4 and 5 resection (191/255, 74.5%) and extended hepatectomy (49/255, 19.2%). Additional operative details are included in Table 2. Within this group, patients in more recent years had a lower likelihood of undergoing concurrent bile duct resection (OR 0.82, 95%CI: 0.78–0.87, p<0.001) and/or major hepatectomy (OR 0.84, 95%CI: 0.80–0.89, p<0.001). Trends over time for surgery are displayed in Figure 1b. For patients with complete resection, no significant relationship was found between year of diagnosis and stage (OR: 1.01, 95%CI: 0.93–1.08, p=0.88).

Figure 1b.

Series Plots for Extent of Surgery and Chemotherapy Strategy by Year for Complete Resection Patients 1992–2015 (N=255)

Time Trends in Chemotherapy Strategy among Patients with Complete Resection

Among patients that underwent a complete resection (n=255), the utilization of neoadjuvant (OR 1.19, 95% CI: 1.05–1.34, p=0.005) and adjuvant chemotherapy (OR 1.13, 95% CI: 1.07–1.20, p<0.001) varied with year of diagnosis, with patients in more recent years more likely to be treated. Trends over time for chemotherapy strategies are also displayed in Figure 1b.

In patients submitted to complete resection (n=255), neoadjuvant chemotherapy had been utilized in 16 (6.3%). Neoadjuvant regimens included: gemcitabine alone (2/16, 12.5%), combination gemcitabine with oxaliplatin or cisplatin (9/16, 56.3%), gemcitabine and other (3/16, 18.8%), 5-FU based therapy (1/16, 6.3%), and irinotecan (1/16, 6.3%). Adjuvant chemotherapy was administered to 78 patients (30.7%). Adjuvant regimens included: gemcitabine alone (32/78, 41%), combination gemcitabine with oxaliplatin or cisplatin (14/78, 17.9%), gemcitabine and other (16/78, 20.5%), 5-FU based chemotherapy (9/78, 11.5%), irinotecan (1/78, 1.3%) or other (6/78, 7.7%).

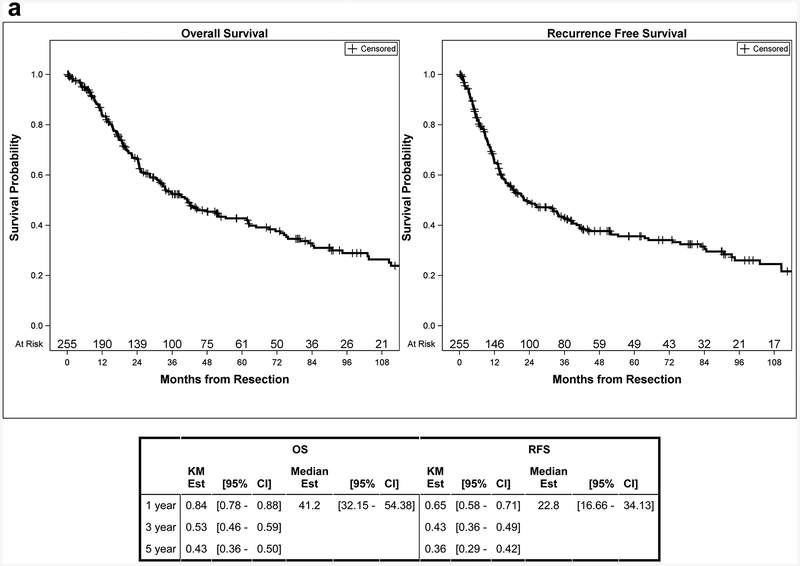

Time Trends in Survival Outcomes

Among all patients that underwent exploration, 315 patients had died with a median OS of 19.6 months (95% CI: 16.7–23.1 months) and a 5-year estimate of 26% (95% CI: 21–31%). Median follow up in survivors was 33.1 months (range: 0–256 months). Patients diagnosed in later years had a significantly lower risk of death (HR 0.97, 95% CI: 0.95–0.99, p=0.002). For patients submitted to complete resection, 149 patients had died by the end of follow up with a median OS of 41.2 months (95% CI: 32.2–54.4 months) and a 5-year estimate of 43% (95% CI: 36–50%). Median follow up in survivors was 36.5 months (range: 0–192 months). Median RFS was 22.8 months (95% CI: 16.7–34.1 months) with a 5-year RFS estimate of 36% (95% CI: 29–42%) (Figure 2a). For patients that underwent a complete resection, no significant association was found between year of diagnosis and OS (HR 0.98, 95% CI: 0.95–1.01, p=0.26) or RFS (HR 0.98, 95% CI: 0.96–1.01, p=0.20).

Figure 2a.

OS and RFS Curves for Complete Resection Patients

Associations between Disease Characteristics and Outcomes

Among all patients undergoing exploration, a complete resection (HR: 0.25, 95%CI: 0.20–0.31, p<0.001) and incidental diagnosis (HR: 0.51, 95%CI: 0.41–0.64, p<0.001) were associated with a lower risk of death. Patients that presented with jaundice (HR: 2.60, 95%CI: 2.00–3.38, p<0.001) or found to have positive lymph nodes (HR: 2.47, 95%CI: 1.83–3.35, p<0.001) were at a higher risk of death compared to patients without those factors. Neoadjuvant treatment was not found to be associated with OS (HR: 1.28, 95%CI: 0.79–2.06, p=0.32) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association between Disease Characteristics and Outcomes

| HR | OS [95% CI] | p-value | HR | RFS [95% CI] | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Surgical Patients | |||||||

| Complete Resection | Yes | 0.25 | [0.20 – 0.31] | <.001 | |||

| No | |||||||

| LN Status* | Positive | 2.47 | [1.83 – 3.35] | <.001 | |||

| Negative | |||||||

| Primary/Incidental | Incidental | 0.51 | [0.41 – 0.64] | <.001 | |||

| Primary | |||||||

| Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy | Yes | 1.28 | [0.79 – 2.06] | 0.32 | |||

| No | |||||||

| Jaundice | Yes | 2.60 | [2.00 – 3.38] | <.001 | |||

| No | |||||||

| Complete Resection Patients | |||||||

| LN Status* | Positive | 2.35 | [1.67 – 3.31] | <.001 | 2.21 | [1.59 – 3.07] | <.001 |

| Negative | |||||||

| Primary/Incidental | Incidental | 0.66 | [0.46 – 0.93] | 0.019 | 0.65 | [0.46 – 0.91] | 0.012 |

| Primary | |||||||

| Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy | Yes | 1.56 | [0.79 – 3.07] | 0.20 | 2.00 | [1.08 – 3.72] | 0.028 |

| No | |||||||

| Jaundice | Yes | 3.09 | [1.83 – 5.22] | <.001 | 2.46 | [1.46 – 4.15] | <.001 |

| No | |||||||

| T-Stage | T3–T4 | 2.42 | [1.74 – 3.37] | <.001 | 2.81 | [2.04 – 3.87] | <.001 |

| T1b-T2 | |||||||

| Margin | Positive | 0.95 | [0.23 – 3.82] | 0.94 | 1.74 | [0.55 – 5.47] | 0.34 |

| Negative | |||||||

| Adjuvant Chemotherapy | Yes | 1.33 | [0.93 – 1.91] | 0.12 | 1.28 | [0.90 – 1.82] | 0.17 |

| No | |||||||

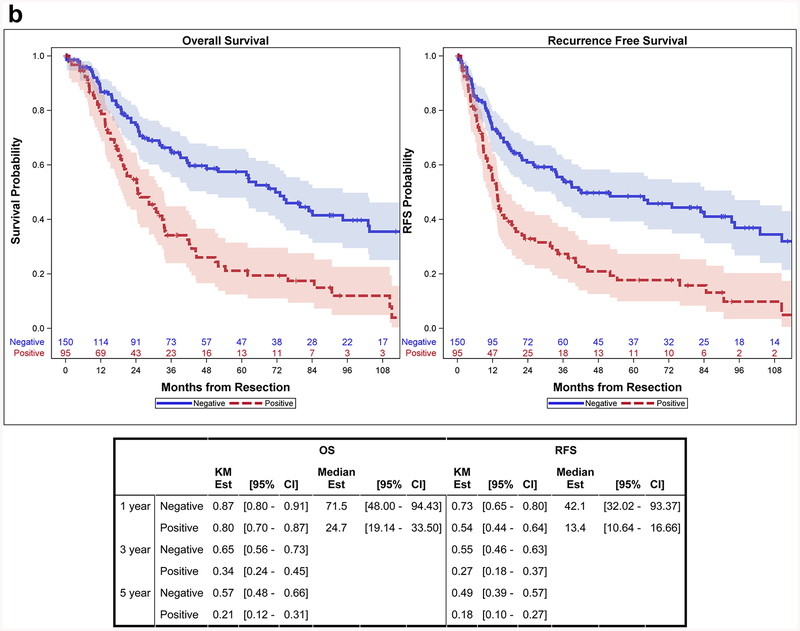

Among patients with complete resection, lymph node metastasis was associated with both a higher risk of death (HR: 2.35, 95%CI: 1.67–3.31, p<0.001) and RFS (HR: 2.21, 95%CI: 1.59–3.07, p<0.001). Median OS was 25 months (95%CI: 19–34 months) for those with positive lymph nodes and 72 months (95%CI: 48–94 months) for those with negative lymph nodes (Figure 2b). Jaundice at presentation was also associated with a higher risk of both death (HR: 3.09, 95%CI: 1.83–5.22, p<0.001) and RFS (HR: 2.46, 95%CI: 1.46–4.15, p<0.001). Median OS was 15 months (95%CI: 10.9–24.7 months) for patients with jaundice and 42 months (95%CI: 33.7–62.4 months) for those without jaundice. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy was associated with a higher risk of recurrence (HR: 2.00, 95%CI: 1.08–3.72, p=0.028), but was not significantly associated with death (HR: 1.56, 95%CI: 0.79–3.07, p=0.20). Adjuvant chemotherapy was not associated with either OS (HR: 1.33, 95%CI: 0.93–1.81, p=0.12) or RFS (HR: 1.28, 95%CI: 0.90–1.82, p=0.17) (Table 3).

Figure 2b.

OS and RFS Curves Stratified by Lymph Node Status for Complete Resection Patients

Discussion

Gallbladder cancer is an aggressive malignancy, and complete resection is the goal for patients without evidence of disseminated disease. In this study, we analyzed GBCA patients that underwent exploration over the course of two decades. Among all patients selected for surgery, the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and the odds of complete resection have increased over time. For those patients with incidental GBCA, the likelihood of finding residual disease at re-operation decreased. For patients with complete resection, the rate of concurrent bile duct resections and major hepatectomies has decreased over time, but year of diagnosis was not associated with differences in OS or RFS. This suggests that less extensive resections have no apparent adverse impact on outcomes. Although the use of neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy has increased, there was no association between these strategies and OS. Pre-operative identification of residual disease, strategies to observe disease biology prior to exploration, and effective chemotherapy are needed to further increase the percentage of patients able to undergo complete resection.

Previous studies in GBCA have demonstrated an associated improvement in OS for patients with complete, curative-intent resection.(1, 2) We also found this association, with complete resection patients having a lower risk of death. Complete resection was achieved in approximately 60% of patients selected for surgery, and the median OS for this group was 41 months. Patients treated in more recent years had increased odds of undergoing a complete resection, suggesting improvements in patient selection over time. Previous studies have demonstrated the poor prognosis associated with jaundice or residual disease at the time of operation.(7, 19) This was reflected in our sample that was selected for exploration, in which the percentage of patients with preoperative jaundice has decreased. These results may indicate that patients explored in more recent years had a decreased likelihood of incomplete resection at the time of surgery. Incorporation of preoperative radiology was beyond the scope of this project, but advances in cross-sectional imaging have likely also altered the profile of patients explored for GBCA over the last two decades. As a surgical series, we are unable to capture the entirety of all patients presenting with GBCA and not referred to a surgeon or selected for exploration. Nonetheless, although patient selection for surgery is multi-factorial, the odds of complete resection at the time of surgery increased over time.

Among all patients subjected to exploration, year of diagnosis was associated with OS in that patients in more recent years had lower risk of death. However, in patients with complete resection of GBCA, there was no association between year of diagnosis and OS or RFS. This suggests that the improved survival among all patients may be, in part, due to those with unresectable disease living longer or it may be a function of power within the complete resection cohort. Patients subjected to exploration with unresectable disease are not indicative of all patients with locally advanced or metastatic GBCA as a whole. As such, this selected group is not necessarily the best sample to assess the contribution of palliative treatments on survival and outcomes in patients with unresectable GBCA. However, this data does provide considerable insight into the time trends and survival outcomes for patients submitted to complete resection of GBCA.

During the study period, the frequency of major hepatectomy declined, even while the rate of complete resection increased in more recent years. Routine bile duct excision and port site resection are no longer recommended as standard therapy.(8) As expected, the rate of these procedures has therefore decreased over time in this study, but this surgical evolution has not had an adverse impact on the survival of patients with resectable GBCA. Complete, curative-intent resection is aimed at achieving a negative margin. There was no association found between year of diagnosis and survival, suggesting that less extensive surgery has not led to worse oncologic outcomes; however, the survival results highlight the need for more effective neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy.

Over the entire study period, approximately 60% of patients submitted to re-operation for incidental GBCA had residual disease, evenly split between locoregional only (33.3%) and distant (29.0%) residual disease. For these patients, a more recent year of diagnosis was associated with decreased odds of finding residual disease, which is strongly associated with poor prognosis, even if completely resected.(19) The reason for this decrease is unclear. While it is possible that residual disease has simply become a less common finding, it would seem more likely that cross-sectional imaging has improved identification of patients with more advanced disease, with subsequent referral for neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Supporting this argument is the observed trend toward increased utilization of neoadjuvant therapy to better select patients with favorable biology.

As stated above, the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy has increased over time, and the majority of regimens include gemcitabine. This strategy has been utilized primarily in patients with locally advanced or high-risk GBCA. Although the likelihood of response and complete resection in patients with locally advanced disease are low, complete resection is possible and associated with longer survival in previous reports.(11, 12) Ausania et al suggested 3-month repeat staging CT prior to surgery for patients with incidental GBCA, as a means of observing disease biology prior to attempted resection. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy accomplishes similar goals and has the potential to limit the number of patients subjected to unsuccessful surgery or with early recurrence.(20) While neoadjuvant chemotherapy was not associated with a difference in OS among patients chosen for surgery, our study did not include patients that received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and were never selected for exploration. A prospective trial, with clear inclusion criteria for locally-advanced and high-risk patients, would better determine the role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in GBCA.(21, 22)

Additionally, for patients with complete resection, the use of adjuvant chemotherapy was not associated with improved RFS in our study, consistent with the recent randomized trial reported by Edeline et al.(14) On the contrary, the BILCAP study demonstrated improved OS with capecitabine compared to observation alone, although GBCA represented a small subset of patients in the trial.(15) Our sample included only 12 patients that had received capecitabine and thus no conclusions on specific chemotherapy regimens can be drawn based on the limited number in this cohort. Further prospective studies, specifically for GBCA, are needed to better assess the role of adjuvant chemotherapy.

A previous study by Konstantinidis et al also analyzed trends in treatment, extent of resection, and outcomes for GBCA at Massachusetts General Hospital.(23) However, this study included patients seen over a much wider range of years (1962–2008) and undergoing varied surgical procedures, ranging from simple cholecystectomy to complete resection with partial hepatectomy. The authors concluded that more extensive recent operations, in the time interval from 1998–2008, were associated with improved survival in GBCA. This is consistent with previous reports about the survival benefit of complete resection over simple cholecystectomy.(24, 25) In our current study, a margin-negative, complete resection with partial hepatectomy was practiced during the entire selected time period. The present study is one of the few that describes GBCA treatment trends over time, during which this practice was standard management. Our findings build upon such previous studies to describe changes in surgical management, treatment, and outcomes for GBCA in the current clinical context.

An additional study using population-based data has also analyzed survival trends for GBCA encompassing similar years. Mayo et al showed that compliance from 1992–2005 with NCCN guidelines for GBCA resection was poor and that there was no significant improvement in survival for patients with surgically managed GBCA over time.(26) However, according to their data, only 13% of patients underwent adequate surgical treatment with a complete resection that also included a partial hepatectomy. Therefore, this study is not a direct comparison to the present single-institution series with complete, definitive resection. While their study addressed compliance with NCCN guidelines and outcomes, it should be viewed in light of the methodology and study-specific limitations.

This study has several limitations, the most important of which is the retrospective analysis and associated selection biases. We did not examine all patients at our institution with gallbladder cancer, such as those that were never referred to a surgeon. Furthermore, the analyses were limited to those that underwent at least exploration. The study attempted to capture the reason(s) that resection was not undertaken, but this often involves complex decision-making that includes clinical characteristics, functional status, and patient desires that is not always apparent in a retrospective analysis. Additionally, there is regional variation between high-volume centers in different countries with regard to presentation and outcomes.(27, 28) Therefore, the results of this study may not necessarily represent trends in GBCA survival across other institutions or geographic regions. The results should be interpreted with regard to the particular practice environment. Correlation between specific chemotherapy regimens and survival was beyond the scope of this project based on the limited sample size of patients treated with each strategy. Thus, we grouped all patients with adjuvant treatment together for OS and RFS survival analyses. In the future, targeted chemotherapy regimens based on mutation profiling may potentially improve response rates and survival.(29, 30) These limitations notwithstanding, this is the largest single-institution surgical series in the United States regarding GBCA, and provides valuable insights into survival trends and prognostic factors over the last two decades. The study illustrates the evolution of surgical therapy for gallbladder cancer over two decades and shows that the trend toward routine use of more limited resections has not been associated with a compromise of oncologic efficacy.

Conclusion

Over the study period, the surgical management of GBCA has evolved to include fewer bile duct resections and major hepatectomies without an adverse impact on survival. There was no significant association between year of diagnosis and OS/RFS for patients with complete resection. Furthermore, patients with GBCA diagnosed in more recent years had increased utilization of neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy. In this subset, no association was found between adjuvant chemotherapy and OS/RFS. Further prospective trials are needed to assess the overall impact of adjuvant chemotherapy on outcomes, limited specifically to patients with GBCA.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This work was supported in part by the NIH/NCI P30 CA008748 Cancer Center Support Grant.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: none

References:

- 1.Fong Y, Jarnagin W, Blumgart LH. Gallbladder cancer: comparison of patients presenting initially for definitive operation with those presenting after prior noncurative intervention. Annals of surgery. 2000. October;232(4):557–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuks D, Regimbeau JM, Le Treut YP, Bachellier P, Raventos A, Pruvot FR, et al. Incidental gallbladder cancer by the AFC-GBC-2009 Study Group. World journal of surgery. 2011. August;35(8):1887–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aloia TA, Jarufe N, Javle M, Maithel SK, Roa JC, Adsay V, et al. Gallbladder cancer: expert consensus statement. HPB: the official journal of the International Hepato Pancreato Biliary Association. 2015. August;17(8):681–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duffy A, Capanu M, Abou-Alfa GK, Huitzil D, Jarnagin W, Fong Y, et al. Gallbladder cancer (GBC): 10-year experience at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Centre (MSKCC). Journal of surgical oncology. 2008. December 1;98(7):485–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pawlik TM, Gleisner AL, Vigano L, Kooby DA, Bauer TW, Frilling A, et al. Incidence of finding residual disease for incidental gallbladder carcinoma: implications for re-resection. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery: official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2007. November;11(11):1478–86; discussion 86–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ito H, Ito K, D’Angelica M, Gonen M, Klimstra D, Allen P, et al. Accurate Staging for Gallbladder Cancer Implications for Surgical Therapy and Pathological Assessment. Annals of surgery. 2011. August;254(2):320–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawkins WG, DeMatteo RP, Jarnagin WR, Ben-Porat L, Blumgart LH, Fong Y. Jaundice predicts advanced disease and early mortality in patients with gallbladder cancer. Annals of surgical oncology. 2004. March;11(3):310–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Angelica M, Dalal KM, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, Blumgart LH, Jarnagin WR. Analysis of the extent of resection for adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder. Annals of surgical oncology. 2009. April;16(4):806–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maker AV, Butte JM, Oxenberg J, Kuk D, Gonen M, Fong Y, et al. Is port site resection necessary in the surgical management of gallbladder cancer? Annals of surgical oncology. 2012. February;19(2):409–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corvera CU, Blumgart LH, Akhurst T, DeMatteo RP, D’Angelica M, Fong Y, et al. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography influences management decisions in patients with biliary cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2008. January;206(1):57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sirohi B, Mitra A, Jagannath P, Singh A, Ramadvar M, Kulkarni S, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced gallbladder cancer. Future oncology (London, England). 2015;11(10):1501–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Creasy JM, Goldman DA, Dudeja V, Lowery MA, Cercek A, Balachandran VP, et al. Systemic Chemotherapy Combined with Resection for Locally Advanced Gallbladder Carcinoma: Surgical and Survival Outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2017. February 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2010. April 8;362(14):1273–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edeline J, Bonnetain F, Phelip JM, Watelet J, Hammel P, Joly J-P, et al. Gemox versus surveillance following surgery of localized biliary tract cancer: Results of the PRODIGE 12-ACCORD 18 (UNICANCER GI) phase III trial. American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Primrose JN, Fox R, Palmer DH, Prasad R, Mirza D, Anthoney DA, et al. Adjuvant capecitabine for biliary tract cancer: The BILCAP randomized study. American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butte JM, Gonen M, Allen PJ, D’Angelica MI, Kingham TP, Fong YM, et al. The role of laparoscopic staging in patients with incidental gallbladder cancer. Hpb. 2011. July;13(7):463–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edge SB, American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010. xiv, 648p. p. [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007. October 16;4(10):e296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butte JM, Kingham TP, Gonen M, D’Angelica MI, Allen PJ, Fong Y, et al. Residual disease predicts outcomes after definitive resection for incidental gallbladder cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2014. September;219(3):416–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ausania F, Tsirlis T, White SA, French JJ, Jaques BC, Charnley RM, et al. Incidental pT2-T3 gallbladder cancer after a cholecystectomy: outcome of staging at 3 months prior to a radical resection. HPB: the official journal of the International Hepato Pancreato Biliary Association. 2013. August;15(8):633–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ethun CG, Postlewait LM, Le N, Pawlik TM, Buettner S, Poultsides G, et al. A Novel Pathology-Based Preoperative Risk Score to Predict Locoregional Residual and Distant Disease and Survival for Incidental Gallbladder Cancer: A 10-Institution Study from the U.S. Extrahepatic Biliary Malignancy Consortium. Annals of surgical oncology. 2016. November 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Creasy JM, Goldman DA, Gonen M, Dudeja V, Askan G, Basturk O, et al. Predicting Residual Disease in Incidental Gallbladder Cancer: Risk Stratification for Modified Treatment Strategies. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery: official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2017. May 08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Konstantinidis IT, Deshpande V, Genevay M, Berger D, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Tanabe KK, et al. Trends in presentation and survival for gallbladder cancer during a period of more than 4 decades: a single-institution experience. Archives of surgery. 2009. May;144(5):441–7; discussion 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bartlett DL, Fong Y, Fortner JG, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH. Long-term results after resection for gallbladder cancer. Implications for staging and management. Annals of surgery. 1996. November;224(5):639–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shih SP, Schulick RD, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, Pitt HA, Choti MA, et al. Gallbladder cancer: the role of laparoscopy and radical resection. Annals of surgery. 2007. June;245(6):893–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayo SC, Shore AD, Nathan H, Edil B, Wolfgang CL, Hirose K, et al. National trends in the management and survival of surgically managed gallbladder adenocarcinoma over 15 years: a population-based analysis. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery: official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2010. October;14(10):1578–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butte JM, Matsuo K, Gonen M, D’Angelica MI, Waugh E, Allen PJ, et al. Gallbladder cancer: differences in presentation, surgical treatment, and survival in patients treated at centers in three countries. J Am Coll Surg. 2011. January;212(1):50–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Butte JM, Torres J, Veras EF, Matsuo K, Gonen M, D’Angelica MI, et al. Regional differences in gallbladder cancer pathogenesis: insights from a comparison of cell cycle-regulatory, PI3K, and pro-angiogenic protein expression. Annals of surgical oncology. 2013. May;20(5):1470–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Javle M, Rashid A, Churi C, Kar S, Zuo M, Eterovic AK, et al. Molecular characterization of gallbladder cancer using somatic mutation profiling. Human pathology. 2014. April;45(4):701–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Javle M, Churi C, Kang HC, Shroff R, Janku F, Surapaneni R, et al. HER2/neu-directed therapy for biliary tract cancer. Journal of hematology & oncology. 2015;8:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.