Abstract

This review article aims to analyze the diagnostic accuracy of the cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) with respect to other imaging methods in detection of bone tissue invasion by oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). The review was carried out of English language studies in PubMed Search, National Library of Medicine, between 1990 and 2017. For each study, sensitivity, specificity, and positive (LR+) and negative (LR−) likelihood ratio, as well as the diagnostic accuracy, and positive and negative predictive values were calculated. Of the 62 collected articles, 7 fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Tests and respective articles included were computed tomography (CT, four studies), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, five studies), C (two studies), single-photon emission tomography (SPECT, two studies), multi-slice computed tomography (MSCT, two studies), and panoramic radiography (PR, two studies). The analytic data show values of LR+ were 14.4 (CT), 37.9 (MRI), 27.8 (CBCT), 25.5 (SPECT), 37.0 (MSCT), 4.8 (PR), respectively. The values of LR− were 0.35 (CT), 0.24 (MRI), 0.10 (CBCT), 0.06 (SPECT), 0.31 (MSCT), and 0.36 (PR), respectively. The positive and negative predictive values for bone tissue invasion by OSCC were 90.31%–74.91% (CT), 90.63%–78.69% (MRI), 80.05%–89.83% (CBCT), 72.97%–95.53% (SPECT), 87.44%–73.74% (MSCT), and 84.245%–69.18% (PR), respectively. The level of scientific evidence available today is weak. To better define the impact of CBCT on clinical decision-making, further studies with uniform methodological approach are needed.

Keywords: Oral cancer, oral squamous cell carcinoma, cone beam computed tomography, diagnostic accuracy, bone invasion

Introduction

Diagnostic imaging is an important adjunct to the clinical assessment of the dental patient. Historically, this has been accomplished by intraoral and extraoral projection radiography, the latter including rotational panoramic radiography. These techniques are based on the transmission, tissue attenuation, and recording of residual X-rays on a single planar medium (either analogue film or a digital receptor). Accurate image formation is based on the optimal geometric configuration of the X-ray generator, patient, and sensor during the activation of the X-ray generator. The image produced is limited to a two-dimensional (2-D) representation of a three-dimensional (3-D) object and tissues [1].

Over the last few years, the use of 3-D information in dentomaxillofacial radiology and surgery planning has consistently grown, firstly because of a more extensive use of MSCT combined with dedicated reformatting software (dentascan) and, more recently, due to the development and diffusion of several pieces of CBCT equipment [2]. Therefore, it is important to know dental CT patient dose for all machines and protocols, to optimize acquisition parameters and to minimize the related radiological risk. Several studies compare the MSCT patient dose with the CBCT patient dose. The CBCT’s orthodontic application potential makes 3-D cephalometric analysis realistic in perspective vision [3]. In dentistry surgery, it is also indicated in the programming of avulsion interventions of molar thirds and dental elements [4], and in dental implantology [5], widening the acquisition of useful data to the accuracy of the positioning of fixtures in the jawbone. CBCT has become widely used for diagnosis of the dentomaxillofacial region; and its usefulness for dental implants, periapical disease, and impacted teeth has been reported. The use of the CBCT, which in the most recent units, allows the recovery of tissue sections with a thickness of up to 0.1 mm. It is also directed to the pre-surgical evaluation of benign and oral cystic neoformations of the oral cavity and post-surgical control of the margins of benign but biologically aggressive lesion resection such as ameloblastoma and keratocysts (keratocystic odontogenic tumors) that may start with a high rate of recurrence [6].

When compared with helical CT, the major advantages of CBCT include high spatial resolution and low radiation dose. Compared with traditional MSCT, CBCT uses a different type of acquisition image. The X-ray source produces a cone-shaped X-ray beam. This makes it possible to capture the image in one sweep, instead of capturing every individual slice separately, as in MSCT [7]. One major advantage is that the patient is scanned in an upright position in CBCT; the soft tissues are not distorted due to gravity, which is the case when a patient is scanned in the supine position in a conventional MSCT [8].

The preoperative evaluation of the bone invasion entity is complicated by the fact that no imaging method alone provides a total reliability in the anatomical measurements of the sections, generating doubts on surgical planning about the extent of resection in compliance with apparently healthy tissue safety margins [9]. This study therefore aimed to analyze, through a literature review, the accuracy of CBCT compared with other latest-generation reconstructive imaging techniques to quantitatively detect the degree of invasion of the bone tissue in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC).

Clinical and Research Consequences

The literature review was conducted using MEDLINE / PubMed Search (National Library of Medicine, NCBI, New PubMed System) between January 1, 1990, and December 1, 2017, and considered seven specific inclusion criteria (1–7) and five exclusion criteria (A–E), used sequentially. Participating subjects were patients of all ages with a histopathological diagnosis of OSCC. The main condition for the screening of the studies was the invasion of bone tissue, maintaining the histopathology as the standard of reference. Excluded studies have been considered such in the light of the first unsatisfied criterion.

Search Strategy

The keywords, according to the MeSH database terminology, National Library of Medicine (NLM), were: cone-beam, CBCT, volumetric CT, digital volume tomography, DVT, volumetric computed tomography, compact computed tomography, compact CT, magnetic resonance imaging, MRI, positron-emission tomography, PET, single-photon emission CT, SPECT, multislice computed tomography, MSCT. Secondary keywords were: “diagnostic accuracy” or “specificity” or “sensitivity”, “oral cancer” or “carcinoma, squamous cell” or “mouth neoplasm” and “invasion oral cancer” or “buccal cancer” or “squamous carcinoma cells”.

Article Selection and Data Analysis

The first selection of articles was carried out on the evaluation of titles and abstracts. The articles considered relevant were analyzed altogether in the full text, on which the inclusion and exclusion criteria were sequentially applied (Table 1). The risk of bias of the included studies was evaluated by two independent reviewers using the criteria outlined in the QUADAS-2 diagnostic analysis methodology, which quantifies the risk level in four key domains or domains: 1) patient selection, 2) index test, 3) reference standard, and 4) flow and timing. A domain was considered as having a low bias risk if all questions were answered “yes”; the risk of bias was “unclear” when at least one question was answered “unclear”. A high risk was attributed when at least one question was answered “no”. Items that showed high bias risk in domains 2) index test, and/or 3) reference standard were excluded [10]. Data analysis for each radiological test and for each study considered eligible compared to the adopted criteria included calculation of sensitivity indexes, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy. Likelihood ratio as well as the positive (PPV) and negative (NPV) predictive values of the tests were computed through Bayesian analysis [11].

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria adopted to evaluate studies

Inclusion criteria:

|

CT: computed tomography; CBCT: cone beam computed tomography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; MSCT: multi-slice computed tomography; OSCC: oral squamous cell carcinoma; PR: panoramic radiography; PET: positron emission tomography; SPECT: single-photon emission computed tomography

Search Results and Selection Process

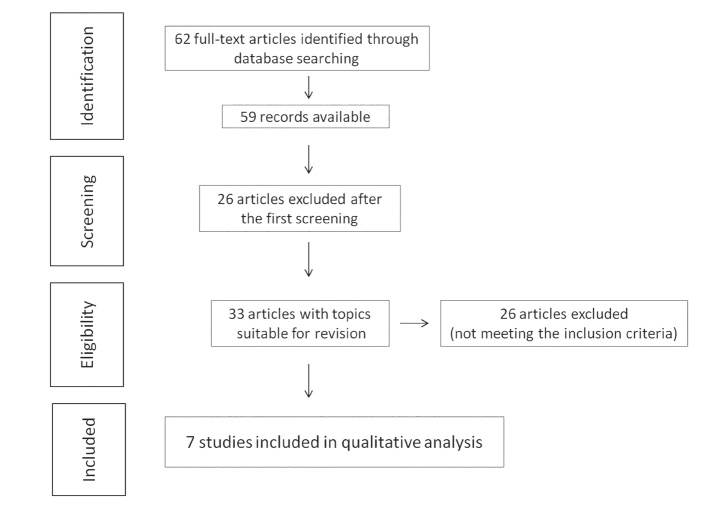

The studies selection process produced 62 full-text articles, of which 59 are available (Figure 1). Of these, after the first verification of the texts, 33 were considered pertinent to the specific theme of the review. A complete review of the 33 articles was followed by applying the above-mentioned selection criteria (Table 1). The selection process was then completed with the exclusion of 26 studies and the inclusion of 7 studies, suitable for subsequent qualitative analysis (Table 2).

Figure 1.

The studies selection process produced 62 full-text articles, of which 59 are available

Table 2.

Studies excluded in relation to the non-responding criterion(s)

| Reason for exclusion (lack of conformity to the review criterions) | References |

|---|---|

| Criterion 1 | -Albuquerque MA, Kuruoshi ME, Oliveira IR, Cavalcanti MG. CT assessment of the correlation between clinical examination and bone involvement in oral malignant tumors. Braz Oral Res 2009; 23: 196–202. -Sigal R, Zagdanski AM, Schwaab G, Bosq J, Auperin A, Laplanche A, et al. CT and MR imaging of squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue and floor of the mouth. Radiographics 1996; 16: 787–810. |

| Criterion 2 | It has been considered in the first screening (see Figure 1). |

| Criterion 3 | -Crecco M, Vidiri A, Angelone ML, Palma O, Morello R. Retromolar trigone tumors: evaluation by magnetic resonance imaging and correlation with pathological data. Eur J Radiol 1999; 32: 182–8. -Dreiseidler T, Alarabi N, Ritter L, et al. A comparison of multislice computerized tomography, cone beam computerized tomography, and single photon emission computerized tomography for the assessment of bone tissue invasion by oral malignancies. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2011; 112: 367–74. -Huntley TA, Busmanis I, Desmond P, Wiesenfeld D. Mandibular invasion by squamous cell carcinoma: a computed tomographic and histological study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1996; 34: 69–74. -Zupi A, Califano L, Maremonti P, Longo F, Ciccarelli R, Soricelli A. Accuracy in the diagnosis of mandibular involvement by oral cancer. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 1996; 24: 281–4. |

| Criterion 4 | -Araki K, Ariji E, Shimizu M, et al. Computed tomography of carcinoma of the upper gingiva and hard palate: correlation with the surgical and histopathological findings. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 1997; 26: 177–82. -Kushraj T, Chatra L, Shenai P, Rao PK. Bone tissue invasion in oral cancer patients: a comparison between orthopantamograph, conventional computed tomography, and single positron emission computed tomography. J Cancer Res Ther 2011; 7: 438–41. -Lwin CT, Hanlon R, Lowe D, et al. Accuracy of MRI in prediction of tumour thickness and nodal stage in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol 2012; 48: 149–54. |

| Criterion 5 | -Acton CH, Layt C, Gwynne R, Cooke R, Seaton D. Investigative modalities of mandibular invasion by squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope 2000; 110: 2050–5. -Brown JS, Griffith JF, Phelps PD, Browne RM. A comparison of different imaging modalities and direct inspection after periosteal stripping in predicting the invasion of the mandible by oral squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1994; 32: 347–59. -Lewis-Jones HG, Rogers SN, Beirne JC, Brown JS, Woolgar JA. Radionuclide bone imaging for detection of mandibular invasion by squamouscell carcinoma. Br J Radiol 2000; 73: 488–93. -Ord RA, Sarmadi M, Papadimitrou J. A comparison of segmental and marginal bony resection for oral squamous cell carcinoma involving the mandible. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1997; 55: 470–7; discussion 477–8. -Rao LP, Das SR, Mathews A, Naik BR, Chacko E, Pandey M. Mandibular invasion in oral squamous cell carcinoma: investigation by clinical examination and orthopantomogram. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004; 33: 454–7. -Schimming R, Juengling FD, Lauer G, Altehöfer C, Schmelzeisen R. Computer-aided 3-D 99mTc-DPD-SPECT reconstruction to assess mandibular invasion by intraoral squamous cell carcinoma: diagnostic improvement or not? J Craniomaxillofacial Surg 2000; 28: 325–30. |

| Criterion 6 | -Dreiseidler T, Alarabi N, Ritter L, et al. A comparison of multislice computerized tomography, cone beam computerized tomography, and single photon emission computerized tomography for the assessment of bone tissue invasion by oral malignancies. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2011; 112: 367–74. |

| Criterion 7 | -Babin E, Desmonts C, Hamon M, Bénateau H, Hitier M. PET/CT for assessing mandibular invasion by intraoral squamous cell carcinomas. Clin Otolaryngol 2008; 33: 47–51 -Brockenbrough JM, Petruzzelli GJ, Lomasney L. Denta Scan as an accurate method of predicting mandibular invasion in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003; 129: 113–7. -Kushraj T, Chatra L, Shenai P, Rao PKK. Bone tissue invasion in oral cancer patients: a comparison between orthopantamograph, conventional computed tomography, and single positron emission computed tomography. J Cancer Res Ther 2011; 7: 438–41. -Rajesh A, Khan A, Kendall C, Hayter J, Cherryman G. Can magnetic resonance imaging replace single photon computed tomography and computed tomography in detecting bony invasion in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008; 46: 11–4. -Vidiri A, Guerrisi A, Pellini R, et al. Multidetector row computed tomography (MDCT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the evaluation of the mandibular invasion by squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) of the oral cavity. Correlation with pathological data. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2010; 29: 73. -Yamamoto Y, Nishiyama Y, Satoh K, et al. Dual-isotope SPECT using 99mTc-hydroxymethylene diphosphonate and 201Tl-chloride to assess mandibular invasion by intraoral squamous cell carcinoma. J Nuclear Med 2002; 43: 1464–8. -Dreiseidler T, Alarabi N, Ritter L, Rothamel D, Scheer M, Zöller JE, et al. A comparison of multislice computerized tomography, cone beam computerized tomography, and single photon emission computerized tomography for the assessment of bone tissue invasion by oral malignancies. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2011; 112: 367–74. -Linz C, Müller-Richter UD, Buck AK, Mottok A, Ritter C, et al. Performance of cone beam computed tomography in comparison to conventional imagingtechniques for the detection of bone invasion in oral cancer. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015; 44: 8–15. -Czerwonka L, Bissada E, Goldstein DP, Wood RE, Lam EW, Yu E, Lazinski D, Irish JC. High-resolution cone-beam computed tomography for assessment of bone invasion in oral cancer: Comparison with conventional computed tomography. Head Neck 2017; 39: 2016–20. |

| Criterion A | -Bolzoni A, Cappiello J, Piazza C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging in the assessment of mandibular involvement in oral-oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: a prospective study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004; 130: 837–43. -Imaizumi A, Yoshino N, Yamada I, et al. A potential pitfall of MR imaging for assessing mandibular invasion of squamous cell carcinoma in the oral cavity. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006; 27: 114–22. -Imola MJ, Gapany M, Grund F, Djalilian H, Fehling S, Adams G. Technetium 99m single positron emission computed tomography scanning for assessing mandible invasion in oral cavity cancer. Laryngoscope 2001; 111: 373–81. -Momin MA, Okochi K, Watanabe H, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of cone beam CT in the assessment of mandibular invasion of lower gingival carcinoma: comparison with conventional panoramic radiography. Eur J Radiol 2009; 72: 75–81. -Mukherji SK, Isaacs DL, Creager A, Shockley W, Weissler M, Armao D. CT detection of mandibular invasion by squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001; 177: 237–43. -Schimming R, Juengling FD, Altehöfer C, Schmelzeisen R. Diagnosis of questionable mandibular infiltration by squamous epithelial carcinomas. 3-D 99mTc-DPD SPECT reconstruction and 18F fluoride PET study: diagnostic advantages or unnecessary expense?. HNO 2001; 49: 355–60. |

| Criterion B | -Dreiseidler T, Alarabi N, Ritter L, et al. A comparison of multislice computerized tomography, cone beam computerized tomography, and single photon emission computerized tomography for the assessment of bone tissue invasion by oral malignancies. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2011; 112: 367–74. |

| Criterion C | -Lane AP, Buckmire RA, Mukherji SK, Pillsbury HC, Meredith SD. Use of computed tomography in the assessment of mandibular invasion in carcinoma of the retromolar trigone. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000; 122: 673–7. |

Studies’ Characteristics and Diagnostic Accuracy

Overall, the studies considered in the qualitative analysis included 406 enrolled patients, of whom 194 were with positive radiological diagnosis for OSCC and bone infiltration, in the various degrees of sensitivity and specificity of different imaging methods. The anatomic sites most affected by neoplastic bone invasion, in order of frequency, were the mandible and the retromolar trigon. In all studies, the reference standard was histopathological analysis, with the description of the microscopic invasion criteria (Table 3). Among the seven included studies, the setting of the studies was prospective for two, [9, 12], retrospective for four [8, 13–15], and prospective and retrospective for one [16]. The numerical representativeness of the patients for each radiologic method analyzed the number of studies (n) was as follows: CT with 242 subjects (n=4), MRI with 214 subjects (n=5), MSCT with 128 subjects (n=2), SPECT with 82 subjects (n=2), CBCT with 81 subject (n=2), and PR with 73 subjects (n=2). In the context of the data collection, for each single study, the results concerning the use of combined techniques, where present, are merely supplementary. The values of the indexes of sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy of each imaging diagnostic method referable to each study are summarized in Table 4.

Table 3.

Types of diagnostic imaging methods, site of the tumors, and invasiveness criteria for the imaging and histopathological findings

| References | Imaging | Anatomical place of the OSCC (n∘) | Diagnostic criteria of image invasion | Criteria for histological invasiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Handschel et al. [15] | CT | Mandible (58) | Three-point scale evaluation of cortical bone erosion. Invasion: periosteal impairment and bone | Three-point classification in relation to the degree of penetration into the cortical bone |

| Oral floor(43) | ||||

| Tongue(6) | ||||

| Gu et al. [14] | CT | Tonsils (23) | Interruption or erosion of the peripheral edge with hyper-attenuation of the signal. Four-point scale of bone evaluation. Invasion probably or surely present Substitution of the peripheral signal hyposensitivity with tumor signal intensity in T1 and T2, or substitution of the hyperintense signal with intermediate tumor signal Dark areas corresponding to regions with high absorption of FDG adjacent to cortical bone showing a visible defect in the accumulation of FDG in the cortical or medullary sites of the same region Combined score scale: score of 4 for multiple tests, or a combined score >2. Like above Like above |

No distinction was made between the invasion of the cortical or bone marrow. Both were considered positive for invasion. |

| MRI | Retromolar trine (8) | |||

| PET/CT | Base of the tongue (6) | |||

| CT+MRI | Oral floor(5) | |||

| CT+PET/CT | Oral area (3) | |||

| MR+PET/CT | Gingiva (1) | |||

| CT+MRI+PET/CT | ||||

| Hendrikx et al. [8] | CBCT | Retromolar trine(8) | Four-point scale in relation to bone compromise. Positive: slight invasion, obvious invasion Like above Like above |

Erosion: bone substituted but without invasion of the medullary spaces, of the mandibular canal and of the parodental ligament. Mandibular invasion: widespread tumor growth within the bone marrow, the root canal and if present in the periodontal ligament space |

| Digital PR | Oral floor (9) | |||

| MRI | Lower alveolar flange (3) | |||

| Van Cann et al. [9] | CT | Retromolar trine (20) Oral floor (31) Lower alveolar flange (13) Mucous membrane (3) |

Absence of cortical bone adjacent to an abnormal soft tissue mass | Bone cortical invasion: bone replacement without invasion of the medullary spaces, the mandibular canal, or the periodontal ligament. Medullary invasion: diffuse growth of the tumor inside the bone marrow, of the root canal and if present in the periodontal ligament space |

| MRI | Retromolar trine (20) Oral floor (31) Lower alveolar flange (13) Mucous membrane (3) |

Replacement of the peripheral signal hyperintensity with tumor signal intensity in T1 and T2, or substitution of the hyperintense signal with intermediate tumor signal. | ||

| Digital PR | Retromolar trine (20) Oral floor (31) Lower alveolar flange (13) Mucous membrane (3) |

n.i | ||

| SPECT | n.i. | |||

| Van den Brekel et al. [13] | MRI | Retromolar process (9) | Tumor within the mandible or hyperintensity of the normal medullary signal replaced by an intermediate signal or an inflammatory eaction in T1 | Impairment of spongiosa and bone marrow |

| CT | Oral floor (20) | Destruction of the external cortical bone and/or bone marrow. | ||

| Digital PR | Three categories: absence of invasion. Minimum erosion. Extended invasion. Invasion: prevalence of bone destruction, replaced by the tumor | |||

| Hakim et al. [12] | CT | Mandible(84) | Semi-quantitative scale with three evaluation points of cortical bone invasion. Bone erosion > at half the thickness of the cortical bone. Penetration of the cortical bone. Infiltration of bone marrow | Bone infiltration was established when tumor cells invaded and perforated the cortical bone (pT4a), according to the UICC/TNM classification for malignant tumors. |

| CBCT | 3-D evaluation of the degree of bone involvement in the three axial, coronal, and sagittal planes, with semi-quantitative scale with three points of assessment of the bone invasion (see above) | |||

| SPECT | ||||

| Kolk et al. [16] | SPECT/CT | Mandible (50) | Classification of images in five categories. Evident involvement of the periosteum and bone. Probable involvement of the periosteum and bone. Not evident involvement of the periosteum and bone. Probably no periosteal involvement and certainly no mandibular erosion. No periosteal and bone involvement | Histological evaluation was conducted on horizontal sections throughout the tumor contact area using standard stains. The analysis of the vertical sections established the state of resection of the margins inside the bone marrow |

| MRI | Like above | |||

| MSCT | Like above |

n.i.: no information; UICC: union for international cancer control

Table 4.

Sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy values for each study

| Reference | Type of study | Subjects | Imaging | True positive | True negative | False positive | False negative | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Diagnostic accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Handschel et al. [15] | Retrospect. | 107 | CT | 38 | 53 | 8 | 8 | 82.6 | 86.9 | 85.0 |

| Gu et al. [14] | Retrospect. | 46 | CT | 5 | 34 | 0 | 7 | 41.7 | 100 | 84.8 |

| MRI | 7 | 33 | 1 | 5 | 58.3 | 97.1 | 87.0 | |||

| PET/CT | 7 | 33 | 1 | 5 | 58.3 | 97.1 | 87.0 | |||

| CT+MRI | 8 | 34 | 0 | 4 | 66.7 | 100 | 91.3 | |||

| CT+PET/CT | 8 | 34 | 0 | 4 | 66.7 | 100 | 91.3 | |||

| MR+PET/CT | 9 | 34 | 0 | 3 | 75.0 | 100 | 93.5 | |||

| CT+MRI+PET/CT | 10 | 34 | 0 | 2 | 83.3 | 100 | 95.7 | |||

| Hendrikx et al. [8] | Retrospect. | 23 | CBCT | 10 | 12 | 0 | 1 | 90.9 | 100 | 95.7 |

| Digital PR | 6 | 11 | 1 | 5 | 54.5 | 91.7 | 73.9 | |||

| MRI | 9 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 83.3 | 100 | 75.8 | |||

| Van Cann et al. [9] | Prospect. | 66 | CT | 25 | 22 | 1 | 18 | 58.1 | 95.7 | 71.2 |

| MRI | 27 | 23 | 0 | 16 | 62.8 | 100 | 75.8 | |||

| PR | N.I. | N.I. | N.I. | N.I. | - | - | - | |||

| SPE CT | N.I. | N.I. | N.I. | N.I. | - | - | - | |||

| Van den Brekel et al. [13] | Retrospect. | 29 | MRI | 17 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 94.8 | 73.0 | 85.7 |

| 23 | CT | 9 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 64.0 | 89.0 | 73.9 | ||

| 26 | PR | N.I. | N.I. | N.I. | N.I. | - | - | - | ||

| Hakim et al. [12] | Prospect. | 78 | MSCT | 21 | 37 | 7 | 13 | 63 | 81 | 75 |

| 62 | SPECT | 29 | 16 | 16 | 1 | 96 | 48 | 73 | ||

| 58 | CBCT | 29 | 16 | 11 | 2 | 93 | 62 | 78 | ||

| Kolk et al. [16] | Prospect. | 30 | SPECT/CT | 19 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Retrospect. | 20 | MRI | 17 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 95 | 94 | 93 | |

| MSCT | 15 | 11 | 0 | 4 | 89 | 100 | 86 | |||

| PR | 14 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 74 | 82 | 77 | |||

| SPECT | 11 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |||

| MSCT | 10 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 89 | 100 | 95 | |||

| MRI | 10 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 95 | 94 | 90 | |||

| PR | 7 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 74 | 82 | 80 |

CT: computed tomography; CBCT: cone beam computed tomography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; MSCT: multi-slice computed tomography; N.I.: none information; PR: panoramic radiography; PET: positron emission tomography; SPECT: single-photon emission tomography

Risk of Bias in the Studies and Likelihood Ratio

As for the bias risk in the studies, the question about the design of case-control study in domain 1 of the QUADAS-2 method was not considered because it was not relevant to the articles being analyzed. The bias risk of the studies included in the review analysis was low to moderate. The major distortion elements are derived from the fact that insufficient information on patient selection was provided, on the time between the execution of the index test and the histopathology analysis and a certain heterogeneity in the application of index tests, such as different scanning thicknesses in CTs and different tesla values in MRI (Table 5). As for the studies are considered and limited to the number of participants, data on likelihood ratio for disease positivity (LR+) and disease-free (LR−) indexes show high specificity for MSCT and MRI, high sensitivity and specificity for CBCT (90.9%; 100%) and SPECT (100%; 100%) respectively, medium-high specificity for CT (82.6%; 86.9%), and low sensitivity for panoramic radiography (74%; 82%). Negative predictive values for bone tissue invasion by OSCC were higher for CBCT (89.83%), and SPECT (95.53%), than the values ascertained in CT, MRI, MSCT, and PR (Table 6).

Table 5.

Methodological quality established according to each QUADAS-2 domain for each single study

| Bias risk | Applicability | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging | Study | Patients selection | Test index | Reference standard | Flow and time | Patient selection | Text index | Reference standard |

| CT | Van den Brekel et al. [13] | ? | + | + | ? | + | + | + |

| Van Cann et al. [9] | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | |

| Gu et al. [14] | ? | + | ? | + | + | + | + | |

| Hanschel et al. [15] | ? | + | + | ? | ? | + | + | |

| MRI | Hendrikx et al. [8] | ? | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Gu et al. [14] | ? | + | ? | + | + | + | + | |

| Van Cann et. [9] | + | + | ? | ? | + | + | + | |

| Kolk et al. [16] | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | |

| Van den Brekel [13] | ? | + | + | ? | + | − | + | |

| CBCT | Hendrikx et al. [8] | ? | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + |

| Hakim et al. [12] | + | + | ? | + | + | + | + | |

| PET/CT | Gu et al. [14] | ? | + | ? | + | + | + | + |

| SPECT | Van Cann et al. [9] | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + |

| Hakim et al. [12] | + | + | ? | + | + | + | + | |

| Kolk et al. [16] | ? | ? | + | ? | ? | ? | + | |

| SPECT/CT | Hakim et al. [12] | + | + | ? | + | + | + | + |

| Kolk et al. [16] | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | |

| MSCT | Hakim et al. [12] | + | + | ? | + | + | + | + |

| Kolk et al. [16] | + | + | + | ? | + | + | + | |

| OPT | Van den Brekel et al. [13] | ? | + | + | ? | + | + | + |

| Hendrikx et al. [8] | ? | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + | |

| Van Cann et al. [9] | + | − | ? | + | + | − | + | |

| Kolk et al. [16] | + | ? | ? | ? | + | + | + |

CT: computed tomography; CBCT: cone beam computed tomography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; MSCT: multi-slice computed tomography; N.I.: none information; PR: panoramic radiography; PET: positron emission tomography; SPECT: single-photon emission tomography

Table 6.

Values of positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR), subdivided by image method, with relative weighted average

| Imaging method | References | Patients n | LR+ (% patients) | LR− (% patients) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Weighted average | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT | Handschel et al. [15] | 107 | 6.30 (44) | 0.20 (44) | 82.61 | 86.89 | LR (T+)=14.80 | Medium high specificity | -The thickness of the scan can influence the sensitivity.15 |

| Gu et al. [14] | 46 | 42.10 (19) | 0.58 (19) | 100.00 | 82.93 | LR (T−)=0.35 | -Possible artifacts generated by metal rehabilitations14 | ||

| Van Cann et al. [9] | 66 | 13.50 (27) | 0.43 (27) | 96.15 | 55.00 | PPV=90.31 | -Underestimate the extent of the bone invasion21 | ||

| Van den Brekel et al. [13] | 23 | 3.31 (9.5) | 0.45 (9.5) | 90.00 | 61.54 | NPV=74.91 | High specificity | -In T1–T2 windows with the use of gadolinium, overestimation of the tumor extension is possible if edema is present.13 | |

| MRI | Gu et al. [14] | 46 | 20.10 (21) | 0.42 (21) | 87.50 | 86.34 | LR (T+)=37.90 | ||

| Hendrikx et al. [8] | 23 | 91.80 (11) | 0.16 (11) | 69.23 | 80.00 | LR (T−)=0.24 | |||

| Van Cann et al. [9] | 66 | 63.40 (31) | 0.37 (31) | 100.00 | 58.97 | PPV=90.63 | -Possible artifacts due to movements, periodontal inflammations and partial volume defects14 | ||

| Van den Brekel et al. [13] | 29 | 3.51 (13.5) | 0.07 (13.5) | 85.00 | 88.89 | NPV=78.69 | |||

| Kolk et al. [16] | 50 | 15.80 (23) | 0.05 (23) | 94.44 | 91.67 | -Signal weakness for cortical bone16 | |||

| CBCT | Hendrikx et al. [8] | 23 | 91.80 (28) | 0.09 (28) | 100.00 | 92.31 | LR (T+)=27.80 | -High sensitivity and specificity. | -Underestimates the extent of bone invasion by the tumor8 |

| Hakim et al. [12] | 58 | 2.44 (71) | 0.11 (71) | 72.50 | 88.89 | LR (T−)=0.10 | -It requires a lower radiation load than the CT and the MSCT8 | -Weak contrast of soft tissues12 | |

| PPV=80.05 | |||||||||

| NPV=89.83 | -Reduced soft tissue distortion due to gravity.8 | -It is altered by inflammatory processes or an increase in hematopoiesis14 | |||||||

| SPECT | Hakim et al. [12] | 62 | 1.85 (76) | 0.08 (76) | 64.44 | 94.12 | LR (T+)=25.50 | -High sensitivity-Identifies hyper-hypometabolic and hypometabolic lesions14 | |

| Kolk et al. [16] | 20 | 99.00 (24) | 0.009 (24) | 100.00 | 100.00 | LR (T−)=0.06 | |||

| PPV=72.97 | |||||||||

| NPV=95.53 | |||||||||

| MSCT | Hakim et al. [12] | 78 | 3.31 (61) | 0.45 (61) | 75.00 | 74.00 | LR (T+)=37.00 | High specificity | -Tendency to underestimate the extent of the tumor8 |

| Kolk et al. [16] | 50 | 89.80 (39) | 0.11 (39) | 100.00 | 73.33 | LR (T−)=0.31 | -Possible artifacts generated by metal rehabilitations9 | ||

| PPV=87.44 | |||||||||

| NPV=73.74 | |||||||||

| PR | Hendrikx et al. [8] | 23 | 6.56 (31) | 0.49 (31) | 85.71 | 68.75 | LR (T+)=4.88 | -Low dosimetry | -Low sensitivity in detecting cortical bone erosion13 |

| Kolk et al. [16] | 50 | 4.11 (68) | 0.31 (68) | 82.35 | 69.23 | LR (T−)=0.36 | -Use to detect periodontal and periapical lesions of not clear interpretation with other modalities9 | ||

| PPV=84.24 | |||||||||

| NPV=69.18 |

LR+: positive likelihood ratio; LR−: negative likelihood ratio; PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value; T+: test positive; T−: test negative

Discussion

The size of the OSCC and the invasion of bone marrow are predictive factors of reduced survival. In contrast, OSCCs with a limited invasion to bone cortical bone show a similar prognosis to those without bone invasion [17]. Histopathologically, two models of bone invasion are established: the erosive or low-risk model and the infiltrative or high-risk model [18]. At present, the radical surgical resection of all tissues infiltrated by the tumor with a safety margin of 7 mm remains the treatment of choice, followed by adjuvant radiotherapy or radio-chemotherapy depending on the pTNM staging of the disease [19].

This assumption implies that the ideal surgical intervention should combine the minimal bone resection with adequate oncological radicality. However, prediction of the degree of bone involvement through preoperative imaging methods remains a matter of debate, as the diagnostic accuracy level of each single method reflects its peculiar utility in planning operative treatment [9].

CBCT is a promising and relatively recent technology when compared to traditional CT, MSCT, and MRI; but is not yet routinely used in preoperative staging procedures in patients with adjacent OSCC or infiltrating the bone structures of the oral cavity [20]. This review of literature aimed at assessing the currently available evidence of CBCT diagnostic accuracy in the diagnosis of bone cancer invasion. The number of apparently small eligible items, distinguished by appropriate methodological quality and diagnostic accuracy, is due to the inclusion and exclusion criteria used, and to the critical evaluation tool (QUADAS-2). The articles analyzed showed a low-to-moderate bias risk (Table 5). Brown and Lewis-Jones [21] published a review in 2001 in which they combined the results of 61 studies, although characterized by a remarkable heterogeneity. The methodology adopted in our study differs from that of Brown and Lewis-Jones as the QUADAS-2 critical review tool has been available since 2003 and reviewed recently [10]. Furthermore, our review has considered histopathological analysis as a benchmark for all the index tests considered. At the end, this study has consistent of the methodological approach used by the recent systematic review carried out by Uribe et al. [22], with its update to the latest published studies.

Specificity data seem to indicate for the MRI, MSCT, CBCT, and to a little bit less for the CT a high diagnostic accuracy index in detecting the negative cases of OSCC invasion. Conversely, there is a marked variation between the maximum values [15] and the minimum [9] of sensitivity, especially for CT (Table 4). This difference could be of multifactorial nature, including a different set of studies, patient selection, and disparity in scanning thickness, ranging from 1.5 mm [9, 13] to 6 mm [13].

On one hand, these findings indicate that current imaging diagnostic tests would probably exclude bone cancer infiltration, on the other, they suggest that clinical use of these tests should be directed to suspect bone infiltration in patients with OSCC rather than being used as a screening method for suspected OSCC cases. In the limited panorama of the two analyzed studies and the total number of patients [8, 12], CBCT shows high sensitivity values but tends to underestimate the extent of bone invasion by OSCC [8]. Concerning this, the causes of the values false negative and false positive of these imaging tests will require further efforts in seeking the possible improvement.

It is further underlined that CBCT alone may not be sufficient to achieve preoperative tumor staging since the “soft tissue window” is still absent from current CBCT scanners, which makes it necessary to use techniques best suited to this aim, such as MRI [12]. Data on the likelihood ratio (LR+, LR−) report for CBCT interesting values on the probability of a positive outcome in the presence of disease (LR+) and disease-free positivity (LR−). This parameter is very significant as it contains sensitivity and specificity data in a single value, providing an indication about the diagnostic utility of the test in question [11] (Table 6).

Consider, however, that although diagnostic accuracy studies are needed, they are not sufficient to provide decision-making guidelines of a public nature, because the impact of the decisions taken about the treatment should also be evaluated. The literature on radiology of the oro-maxillofacial district is predominantly represented by case reports/series, transverse or prevalence studies, technical efficacy studies, and accuracy. These studies do not provide considerable evidence for clinical decision-making nor consider the impact of the diagnostic imaging on patient care [23]. One of the limitations in interpreting the results of this review lies in the small number of studies and, consequently, of casuistry on which the diagnostic accuracy parameters for the different imaging methods analyzed were calculated.

The consultation of a single database and the restriction in the choice to the English language alone could have potentially reduced the availability of studies meeting the selection criteria [24]. To the evaluations exposed, we add that the results of the following study suggest how much the diagnostic accuracy can vary with regard to the criteria used to determine bone invasion by OSCC. An observation to consider in future studies concerns various levels of the QUADAS-2 evaluation method. The first level refers to the selection of patients: since the selection is based on the TNM classification, it would be appropriate to specify the number of patients in each stage of development of the disease, with the aim of better defining the percentage of clinically classifiable subjects “with invasion” and “without invasion” by OSCC. The second level is related to the index test: to consider cortical erosion as a criterion of invasion of the bone it is necessary to establish an agreement for the minimum thickness of the scan (CT and MSCT) to determine the radiological detection [13, 14]. The third level regards the reference standard: according to the first level, a common histopathological criterion of bone invasion should be indicated, to allow the calculation of sensitivity and specificity values for the different diagnostic, instrumental, and laboratory levels, and to facilitate the comparison between the studies. The fourth level, no less important, refers to the flow and time and consists, given the rapid growth of diseases such as oral cancer, in specifying the indication of the time elapsed between the execution of the index test and the reference standard.

The CBCT diagnostic method demonstrates high diagnostic accuracy as well as a high negative predictive value in detecting bone invasion in patients with oral cancer. However, the available evidence is quantitatively low and characterized by poor quality. The standardization of the methodology approach along the lines shared in the planning of future studies will thus have a greater impact on the decision-making process of the clinician in pursuing the best cost-benefit ratio, aimed at treating the patient.

Footnotes

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author contributions: Concept – G.P.B., V.C.; Design – G.P.B.; V.C., F.S., A.B.G., F.C.; Supervision - F.S., A.B.G., F.C.; Analysis and /or Interpretation – G.P.B., V.C., F.S., A.B.G., F.C.; Literature Search – G.P.B., V.C.; Writing – G.P.B. Candotto Valentina; Critical Reviews – F.S., A.B.G., F.C.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1.Scarfe WC, Li Z, Aboelmaaty W, Scott SA, Farman AG. Maxillofacial cone beam computed tomography: essence, elements and steps to interpretation. Aust Dent J. 2012;57(Suppl 1):46–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2011.01657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rampado O, Bianchi SD, Peruzzo Cornetto A, Rossetti V, Ropolo R. Radiochromic films for dental CT dosimetry: a feasibility study. Phys Med. 2014;30:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmp.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheung LK, Chan YM, Jayaratne YS, Lo J. Three-dimensional cephalometric norms of Chinese adults in Hong Kong with balanced facial profile. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112:e56–73. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oenning AC, Neves FS, Alencar PN, Prado RF, Groppo FC, Haiter-Neto F. External root resorption of the second molar associated with third molar impaction: comparison of panoramic radiography and cone beam computed tomography. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;72:1444–55. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balasundaram A, Gurun D, Neely A, Ash-Rafzadeh A, Ravichandra J. Novel CBCT and Optical Scanner-Based Implant Treatment Planning Using a Stereolithographic Surgical Guide: A Multipronged Diagnostic Approach. Implant Dent. 2014;23:401–6. doi: 10.1097/ID.0000000000000128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmad M, Jenny J, Downie M. Application of cone beam computed tomography in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Aust Dent J. 2012;57(Suppl 1):82–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2011.01661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bittermann G, Scheifele C, Prokic V, et al. Description of a method: Computer generated virtual model for accurate localisation of tumour margins, standardised resection, and planning of radiation treatment in head & neck cancer surgery. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2013;41:279–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hendrikx AWF, Dieleman T, Maal F, Van Cann E, Merkx MA. Cone-beam CT in the assessment of mandibular invasion by oral squamous cell carcinoma: results of the preliminary study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39:436–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Cann EM, Koole R, Oyen WJG, et al. Assessment of mandibular invasion of oral squamous cell carcinoma by various modes of imaging. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;37:535–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whiting PF, Rutjes AWS, Westwood ME, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Straus SE, Scott Richardson WS, Glasziou P, Haynes RB. Evidence-based medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM. 3rd ed. Edinburgh, UK: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hakim SG, Wieker H, Trenkle T, et al. Imaging of mandible invasion by oral squamous cell carcinoma using computed tomography, cone-beam computed tomography and bone scintigraphy with SPECT. Clin Oral Invest. 2014;18:961–7. doi: 10.1007/s00784-013-1042-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van den Brekel MWM, Runner RW, Smeele LE, Tiwari RM, Snow GB, Castelijns JA. Assessment of tumour invasion into the mandible: the value of different imaging techniques. Eur Radiol. 1998;8:1552–7. doi: 10.1007/s003300050585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu DH, Yoon DY, Park HC, et al. CT, MR, 18F-FDG PET/CT, and their combined use for the assessment of mandibular invasion by squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity. Acta Radiol. 2010;51:1111–9. doi: 10.3109/02841851.2010.520027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Handschel J, Naujoks C, Depprich RA, et al. CT-scan is a valuable tool to detect mandibular involvement in oral cancer patients. Oral Oncology. 2012;48:361–6. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2726-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolk A, Schuster T, Chlebowski A, et al. Combined SPECT/CT improves detection of initial bone invasion and determination of resection margins in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck compared to conventional imaging modalities. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41:1363–74. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2726-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebrahimi A, Murali R, Gao K, Elliott MS, Clark JR. The prognostic and staging implications of bone invasion in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2011;117:4460–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaw RJ, Brown JS, Woolgar JA, Lowe D, Rogers SN, Vaughan ED. The influence of the pattern of mandibular invasion on recurrence and survival in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2004;26:861–9. doi: 10.1002/hed.20036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah JP, Gil Z. Current concepts in management of oral cancer-surgery. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Momin MA, Okochi K, Watanabe H, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of cone-beam CT in the assessment of mandibular invasion of lower gingival carcinoma: comparison with conventional panoramic radiography. Eur J Radiol. 2009;72:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown JS, Lewis-Jones H. Evidence for imaging the mandible in the management of oral squamous cell carcinoma: a review. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;39:411–8. doi: 10.1054/bjom.2001.0717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uribe S, Rojas LA, Rosas CF. Accuracy of imaging methods for detection of bone tissue invasion in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Dentomaxillofal Radiol. 2013;42 doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20120346. 20120346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dahabreh IJ, Chung M, Kitsios GD, et al. Comprehensive overview of methods and reporting of meta-analyses of test accuracy. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim IH, Patel MJ, Hirt SL, Kantor ML. Clinical research and diagnostic efficacy studies in the oral and maxillofacial radiology literature: 1996–2005. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2011;40:274–81. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/81879482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]