Abstract

Purpose

We review two recent neuroanatomical studies of children who stutter (CWS), one that examines white matter integrity and the other that focuses on cortical gray matter morphology. In both studies, we sought to examine differences between children whose stuttering persists (“persistent”), children who recovered from stuttering (“recovered”), and their nonstuttering peers (“controls”).

Method

Both of the reviewed studies use data from a large pediatric sample spanning preschool- to school-age children (3–10 years old at initial testing). Study 1 focused on surface-based measures of cortical size (thickness) and shape (gyrification) using structural magnetic resonance imaging, whereas Study 2 utilized diffusion tensor imaging to examine white matter integrity.

Results

In both studies, the main difference that emerged between CWS and fluent peers encompassed left hemisphere speech motor areas that are interconnected via the arcuate fasciculus. In the case of white matter integrity, the temporoparietal junction and posterior superior temporal gyrus, both connected via the left arcuate fasciculus, and regions along the corpus callosum that contain fibers connecting bilateral motor regions were significantly decreased in white matter integrity in CWS compared to controls. In the morphometric study, children who would go on to have persistent stuttering specifically had lower cortical thickness in ventral motor and premotor areas of the left hemisphere.

Conclusion

These results point to aberrant development of cortical areas involved in integrating sensory feedback with speech movements in CWS and differences in interhemispheric connectivity between the two motor cortices. Furthermore, developmental trajectories in these areas seem to diverge between persistent and recovered cases.

Stuttering affects approximately 5% of all preschool-age children. Onset of stuttering typically occurs between 2 and 4 years of age (Yairi & Ambrose, 1999, 2013), coinciding with a period of rapid speech and language development. Up to 80% of children who stutter (CWS) will recover with or without intervention. It is reported that natural recovery occurs, in most cases, within 2 years of stuttering onset (Yairi & Ambrose, 1999). The pathophysiological bases for childhood stuttering remain unclear, and we know little about the possible ameliorating factors behind recovery or risk factors for persistent stuttering that occurs in 1% of the general population. Because stuttering onset and eventual recovery in most cases occur during early childhood, examining children close to stuttering onset is considered critical in furthering our understanding of neural risk factors associated with persistent stuttering.

Compared to research that focused on adults who stutter, investigations into brain development trajectories in CWS have been scarce. While there are significant practical challenges when conducting neuroimaging studies with children, these studies are nevertheless important as they have the potential to overcome some limitations that are inherent in investigations that only involve adults. For example, examining children close to symptom onset could help elucidate possible confounding issues that make it difficult to determine what is a trait-based difference related to etiology of stuttering, compared to a difference that may be related to a result of having stuttered for a number of years.

Among studies investigating brain anatomy differences in CWS, the most common finding across morphometric studies of CWS (Beal, Gracco, Brettschneider, Kroll, & De Nil, 2013; S. E. Chang, Erickson, Ambrose, Hasegawa-Johnson, & Ludlow, 2008; S. E. Chang & Zhu, 2013) is anomalous structure within the left hemisphere speech network. For example, an early study by S. E. Chang et al. (2008) used voxel-based morphometry to compare gray matter volume (GMV) in CWS and fluent children. The largest differences in GMV were found in the left inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) and left precentral gyrus (which includes motor and premotor cortex); these areas are both crucial centers in the speech production network (Guenther, 2006). CWS had smaller GMV in these areas than controls. Beal et al. (2013) also found smaller IFG GMV in CWS compared to fluent children, although in this study the differences were found bilaterally. S. E. Chang and Zhu (2013) found structural differences between CWS and fluent children in white matter tracts primarily within the left hemisphere speech network, including connections between putamen, auditory cortex, supplementary motor area (SMA), and insula. Analyses of resting-state functional connectivity in the same subjects largely corroborated the tractography results. In another study of white matter development, S. E. Chang, Zhu, Choo, and Angstadt (2015) reported decreases in white matter integrity in a number of areas along the left superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF), as well as parts of the corpus callosum (CC; see Figure 2). Among these, the left IFG and parts of the CC showed the expected age-related increases in fractional anisotropy (FA) for controls, but not in CWS.

Figure 2.

Summary of significant group differences in the left hemisphere cortical morphology. Areas showing significant group differences are plotted on an inflated cortical surface template. See caption of Figure 1 for anatomical parcel abbreviations. aCO = anterior central operculum; midPMC = middle premotor cortex temporale; SMA = supplementary motor area; vMC = ventral motor cortex; vPMC = ventral premotor cortex. Reprinted from Garnett et al., ‘Anomalous Morphology in Left Hemisphere Motor and Premotor Cortex of Children Who Stutter,’ Brain, Vol. 141, pp. 2670–2684, by permission of Oxford University Press. Copyright © 2018 Oxford University Press.

Related, although not a study of anatomy, Walsh et al. (2017) used functional near-infrared spectroscopy to examine brain activity in bilateral IFG and superior temporal gyrus (STG) cortical areas during continuous speech production. The left IFG/ventral premotor regions were the only areas showing significantly aberrant patterns in the hemodynamic response during the speech production task in CWS compared to controls. Group differences in the right hemisphere homologues (IFG, STG) were not significant (Walsh et al., 2017). These findings corroborate results from research focused on brain structural changes in stuttering, which have pointed to probable anomalous development of the left perisylvian auditory–motor cortical structures and the white matter tracts that interconnect them.

In this article, we review two recent neuroanatomical studies from our group, one that examines cortical gray matter morphology differences and the other that focuses on white matter integrity differences. The relationship between white and gray matter maturation is not well understood, but several studies report links between white matter maturation, long-range brain connectivity, and cortical maturation. Cortical gray matter maturation relates to development of brain functions, while white matter development promotes propagation of nerve signals from one cortical area to another, contributing to both gray matter development and overall cerebral connectivity and development (Friedrichs-Maeder et al., 2017; Tau & Peterson, 2009). While early neural maturation is driven by genetic molecular cues, postnatal neural development is highly dependent on environmental cues and experience-dependent neural activity, which leads to refinements of neural circuits via synaptic, dendritic, axonal outgrowth, and pruning. Gray matter development occurs sequentially from subcortical areas to primary sensory and motor cortical regions and then to secondary, tertiary, and higher order regions. It has been shown that speech-language–associated regions such as the left IFG and bilateral STG show the most protracted growth trajectories, occurring up to late adolescence (Gogtay et al., 2004). White matter development also occurs from a primary/caudal to rostral direction toward higher order areas occurring later during development, heavily dependent on experience and training (Barnea-Goraly et al., 2005; Brody, Kinney, Kloman, & Gilles, 1987; Girard, Raybaud, & du Lac, 1991; Paus et al., 2001).

In the two studies reported here, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)–based indices of white and gray matter brain maturation included measures derived from diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and surface-based morphometric measures of shape and size of cortical areas from structural MRI, respectively. DTI uses a special MRI sequence (Stejskal & Tanner, 1965) that is sensitized to the movement of water molecules, and the data allow derivation of quantitative measures that reflect the microscopic structure of white matter tissue (Le Bihan & Johansen-Berg, 2012). The measure used in Study 2 below utilized FA, a measure that quantifies the extent to which water molecules move in a preferential (i.e., anisotropic) direction. FA is a scalar ranging from 0 to 1, with 0 being almost absolute isotopic movement while 1 being almost absolutely anisotropic movement. High FA values would be seen in structures such as the CC, while low FA values would be seen in cerebrospinal fluid or, to a lesser extent, in gray matter areas. FA values are influenced by myelination, axon diameter, axonal packing, and the presence of crossing fibers. FA, in general, increases in white matter areas in most brain areas with development but decreases with edema or a demyelinating condition, such as multiple sclerosis. As reviewed previously, one of the most commonly reported findings in stuttering has been that FA is significantly decreased in left hemisphere tracts (e.g., SLF, arcuate fasciculus) in both CWS and adults who stutter.

In the case of examining gray matter, we report in Study 1 a surface-based morphometric analysis of structural MRI data (spoiled gradient recalled). We focus here on morphology of the cerebral cortex, investigating two aspects of cortical morphology in separate analyses: region of interest (ROI) size and gyrification. For the gyrification analysis, the FreeSurfer measures local gyrification index, which characterizes the amount of cortex within sulcal folds compared to the outer cortex, was the dependent variable. For the ROI size analysis, we first performed a dimensionality reduction analysis using all four FreeSurfer measures of ROI size (cortical thickness, surface area, volume, and thickness-to-area ratio). We utilized image processing and statistical analysis methods that provide increased sensitivity to group differences in morphology than those used in prior studies, including cortical surface reconstruction (Dale, Fischl, & Sereno, 1999) and a functional–anatomical parcellation of cerebral cortex designed specifically for studies of speech that account for individual differences in cortical anatomy, thereby providing increased statistical power (Nieto-Castanon, Ghosh, Tourville, & Guenther 2003; Tourville & Guenther, 2012). This is the first study to investigate local gyrification in CWS. As noted above, this morphometric feature has been shown to differ in speech-related cortical areas of adults who stutter compared to fluent adults.

In both studies, we sought to examine differences between children whose stuttering persists (“persistent”), children who recovered from stuttering (“recovered”), and their nonstuttering peers (“controls”). Both of the reviewed studies use data from a large pediatric sample spanning preschool- to school-age children (3–10 years old at initial testing). This allowed us, for the first time, to examine structural differences encompassing a data set that includes many children close to stuttering onset, as well as how any results change with age. The relatively large data set comprising young children also permitted us to compare findings between the persistent and recovered groups, as the data are part of a longitudinal study that tracks stuttering status and brain morphometry of CWS over the course of several years.

Method

Methods Common to Both Studies

Participant Recruitment and Behavioral Testing

Both of the studies we review below use data from the first cohort of the largest neuroimaging data set of young CWS and their fluent peers. Children enter the study when they are between 3 and 10 years of age and visit the lab for testing once a year for up to 4 years. Each yearly visit, children complete a battery of standardized speech, language, and cognitive tests; an audiometric hearing screening; and an oral–motor screening, details of which can be found in S. E. Chang et al. (2015). Children with scores below 2 SDs of the mean on any of the standardized assessments were excluded from further participation. In order to characterize stuttering status, severity, and eventual recovery/persistence, children provided spontaneous speech samples with a parent and a certified speech-language pathologist. These samples were collected each year, with up to four yearly samples from each child. We calculated the percentage of disfluent syllables based on narrative samples and a monologue (storytelling) using a pictures-only book (Frog, Where Are You? by Mayer, 1969). The Stuttering Severity Instrument–Fourth Edition (SSI-4; Riley & Bakker, 2009) was used to examine the frequency and duration of disfluencies occurring in the speech sample, as well as any physical concomitants associated with moments of stuttering; all of these measures were incorporated into a composite stuttering severity rating. All study procedures were approved by the Biomedical and Health Institutional Review Board at Michigan State University, where the study was conducted (IRB 09-810). All parents provided informed consent, and all children provided assent before participating.

Children designated into the stuttering group were diagnosed with stuttering during their initial visit. To determine eventual recovery or persistence, a combination of objective and subjective measures was used. In addition to the SSI-4 composite score, determination of recovery status also required the consideration of percent occurrence of stuttering-like disfluencies (%SLD) in the speech sample (> 3 for persistent) as well as clinician and parental reports. Specifically, a child was considered recovered if the composite SSI-4 score was below 10 at the second visit or thereafter and %SLD was lower than 3. A child was categorized as persistent if the SSI-4 score was at or higher than 10 (corresponding to “very mild” in the SSI-4 severity classification) at the second visit or thereafter, and the onset of stuttering had been at least 36 months prior to the most recent visit. Similar criteria were used to determine persistence versus recovery in stuttering children in previous studies (Yairi & Ambrose, 1999; Yairi, Ambrose, & Cox, 1996). For controls, the inclusion criteria included never having been diagnosed with stuttering, no family history of stuttering, lack of parental concern for their child's fluency, and a %SLD of below 3.

Information related to parent impression is obtained from the case history and includes questions, such as “Do you feel that your child's stuttering has changed?” and follow-up questions from the clinician. Additional questions include types of disfluencies, secondary behaviors, situations that make the stuttering better or worse, awareness of disfluencies, teasing, and speech therapy services. Clinician impression is based on frequency and type of disfluencies as well as the presence of secondary behaviors. Along with traditional measures such as %SLD and the SSI, this information is collected/completed on each of the yearly visits and used to determine fluency status. The determination of persistence versus recovery is made by triangulating the objective data (the SSI, %SLD), parent impression, and clinician impression. Additionally, if a child exhibited less than 3% SLD during a visit but the parent reported the child was exhibiting an atypically mild day and confirmed continued stuttering in the past 6 months, this child would be considered persistent and was followed up/confirmed in later visits. The same was true for recovery: If there was greater than 3% SLD, mostly whole-word repetitions, a score of very mild or below on SSI, and the parent indicated at least 6 months of continued fluency, that child was categorized as recovered. The persistence versus recovery status was monitored at each longitudinal visit for each child.

MRI Training and Acquisition

All children were trained during a separate visit with a mock MRI scanner to familiarize them with the MRI environment and procedures and to practice keeping still for stretches of time. This mock training included listening to recordings of MRI scanning noises, which helped acclimate the children to the loud MRI sounds during scanning. The MRI scanning protocol was repeated yearly, with repeat scans occurring, on average, every 12 months.

All MRI scans were acquired on a GE 3T Signa HDx MR scanner with an eight-channel head coil. During each session, whole-brain T1-weighted inversion recovery fast spoiled gradient recalled images (3D) with cerebrospinal fluid suppressed were obtained with the following parameters: time of echo = 3.8 ms, time of repetition of acquisition = 8.6 ms, time of inversion = 831 ms, repetition time of inversion = 2,332 ms, flip angle = 8°, field of view = 25.6 cm × 25.6 cm, matrix size = 256 × 256, slice thickness = 1 mm, and receiver bandwidth = ± 20.8 kHz.

After T1 data acquisition, first and high-order shimming procedures were carried out to improve magnetic field homogeneity. The DTI data were acquired with a dual spin echo echo-planar imaging sequence for 12 min 6 s with the following parameters: 48 contiguous 2.4-mm axial slices in an interleaved order, field of view = 22 × 22 cm, matrix size = 128 × 128, number of excitations = 2, echo time = 77.5 ms, repetition time = 13.7 s, 25 diffusion-weighted volumes (one per gradient direction) with b = 1000 s/mm2, one volume with b = 0, and parallel imaging acceleration factor = 2. One staff member sat inside the scanner room next to the child at all times to monitor the child's comfort and to ensure cooperation during scanning. During acquisition of volumetric T1-weighted scans and DTI scans, the children viewed a movie to help them stay still. A research staff member sat next to the child to ensure comfort and compliance throughout the scanning procedure, which also included acquisition of a resting state fMRI data that are not discussed here. The total scan time was about ~40 min.

Study 1: Anomalous Morphology in Left Hemisphere Motor and Premotor Cortex of CWS

Garnett et al. (2018) focused on cortical morphology by examining measures of the size (cortical thickness) and shape (local gyrification) of cortical ROIs. We aimed to detect differences in brain structure between children who stuttered initially but recovered (the recovery group), children whose stuttering persisted (the persistent group), and fluent children (the control group). Given the previous findings of CWS reviewed above, we expected that, compared to children who recover from stuttering and their fluent peers, children with persistent stuttering would show structural differences in the left hemisphere speech network and related sensorimotor and higher order cognitive areas involved in speech production (Guenther, 2016). For example, aberrant connectivity within the default mode network and its connectivity with other large-scale networks such as the attention networks (e.g., dorsal attention network, ventral attention network) were shown to be specific to persistent CWS (e.g., S. E. Chang et al., 2018).

Detailed methods, materials, and participants can be found in Garnett et al. (2018). In brief, participants included 70 children (36 CWS, 14 girls; 25 persistent; 34 controls, 17 girls) between 37.1 and 129.2 months of age. To examine the morphological structure of the cerebral cortex, including measures of the size and shape of cortical ROIs, we used FreeSurfer software (Version 5.3.0; http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/). FreeSurfer uses high-resolution anatomical T1-weighted images from each subject's MRI to create a three-dimensional reconstruction of the surface of the brain. The software also automatically creates separate gray (pial surface) and white matter segmentation, which can be overlaid onto the reconstructed surfaces. Manual quality checks were completed on all scans, and edits were sometimes necessary to ensure that the automatic segmentation was done accurately. These were completed using the guidelines from the FreeSurfer tutorial (https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/fswiki/FsTutorial/TroubleshootingData), after which the surface reconstructions were regenerated. This segmentation helps distinguishes between gray and white matter structures within the brain and allows FreeSurfer to automatically calculate five measures, including thickness, area, volume, thickness-to-area ratio, and local gyrification index (a measure of the folding patterns) of specified ROIs. In this project, we used a specialized atlas that divides each subject's cortical surface into 62 distinct anatomical regions (parcels) per hemisphere based on individual anatomical landmarks according to the SLaparc parcellation system (Tourville & Guenther, 2012) that focus on perisylvian speech regions.

Data Analysis

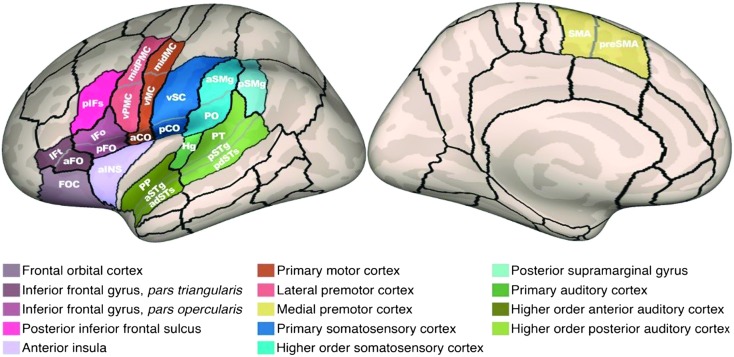

Details regarding selection and analysis of morphometric measures can be found in Garnett et al. (2018). For the purposes of the present discussion, we highlight the statistically significant findings from the cortical thickness, surface area, and local gyrification index measures. The chosen morphometric measures for ROI size and gyrification were submitted to analyses of covariance that allowed us to compare persistent, recovered, and control groups on these measures, as well as determine if any effects of age were present, while rigorously controlling for multiple comparisons. These effects were explored in 14 left hemisphere speech network ROIs as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Functional regions of interest (fROIs; color-coded shading). The fROIs and associated anatomical parcels are shown on an inflated reconstruction of a representative left hemisphere cortical surface. aCO = anterior central operculum; adSTs = anterior dorsal superior temporal sulcus; aINS = anterior insula; aFO = anterior frontal operculum; aSMg = anterior supramarginal gyrus; aSTg = anterior superior temporal gyrus convexity; FOC = frontal orbital cortex; Hg = Heschl's gyrus; IFo = inferior frontal gyrus pars opercularis convexity; IFt = inferior frontal gyrus pars triangularis convexity; midMC = middle motor cortex; midPMC = middle premotor cortex; pCO = posterior central operculum; pdSTs = posterior dorsal superior temporal sulcus; pFO = posterior frontal operculum; pIFs = posterior inferior frontal sulcus; PO = parietal operculum; PP = planum polare; preSMA = pre–supplementary motor area; pSMg = posterior supramarginal gyrus; pSTg = posterior superior temporal gyrus convexity; PT = planum temporale; SMA = supplementary motor area; vMC = ventral motor cortex; vPMC = ventral premotor cortex; vSC = ventral somatosensory cortex. Reprinted from Garnett et al., “Anomalous Morphology in Left Hemisphere Motor and Premotor Cortex of Children Who Stutter,” Brain, Vol. 141, pp. 2670–2684, by permission of Oxford University Press. Copyright © 2018 Oxford University Press.

Results

A summary of the significant group differences from the hypothesis-based analyses plotted on an inflated cortical surface is provided in Figure 2. Analysis of these functional ROIs identified significant group cortical thickness differences in four functional ROIs: middle premotor cortex (midPMC), ventral motor cortex (vMC), ventral premotor cortex (vPMC), and anterior central operculum (aCO). In the mid-PMC, the persistent group had lower cortical thickness compared to the recovery and control groups (see Figure 3a). Similarly, in the vMC, the persistent group had lower cortical thickness than the recovery group (see Figure 3b). In vPMC, cortical thickness decreased with age in the persistent group but not in the control group (see Figure 3c). Finally, in aCO, group effects (see Figure 3d) were driven by a combination of both main between-groups differences and group-by-age interactions, but no significant individual effects. The data were consistent with the vMC finding of lower cortical thickness in persistent compared to recovered children, despite no significant pairwise group differences. Along with the adjacent vMC, this region of the Rolandic operculum has been shown to have aberrant white matter tracts (S. E. Chang et al., 2008; Sommer, Koch, Paulus, Weiller, & Büchel, 2002). The lack of significant group differences in this region may indicate that this specific ROI does not contribute in a major way to the differentiation of persistent versus recovered groups or recovery but is rather related to stuttering risk in general.

Figure 3.

Premotor, motor, and medial motor cortical areas showing significant group differences in morphometry. Significant morphometric group differences (P-FDR < .05) were identified in analyses of covariance of group differences in the left hemisphere speech network morphology, plotted as a function of age. See caption of Figure 1 for anatomical parcel abbreviations. aCO = anterior central operculum; midPMC = middle premotor cortex temporale; SMA = supplementary motor area; vMC = ventral motor cortex; vPMC = ventral premotor cortex. Reprinted Garnett et al., “Anomalous Morphology in Left Hemisphere Motor and Premotor Cortex of Children Who Stutter,” Brain, Vol. 141, pp. 2670–2684, by permission of Oxford University Press. Copyright © 2018 Oxford University Press.

Turning to gyrification (see Figures 3e and 3f), the local gyrification analysis identified both significant main and interaction effects in SMA, consistent with a decrease in gyrification with age in the recovery group but not in the persistent or control groups. It also revealed a significant main effect in pre-SMA consistent with reduced gyrification in the recovery group compared to the persistent or control groups.

Summary of Study 1

To summarize, Study 1 reported the first surface-based cortical analysis in childhood stuttering. The primary neuroanatomical findings that differentiated the persistent and recovered groups were in cortical thickness in the left motor and lateral premotor areas. Recovery from stuttering was linked to decreased gyrification in the left SMA/pre-SMA. One interpretation is that long-range connectivity between regions may be supported by these structural differences, which in turn better support improvements in fluent speech production. These results provide novel information that contributes to our expanding knowledge base on the neural bases of stuttering and the possible basis for chronicity versus recovery from stuttering.

Study 2: White Matter Neuroanatomical Differences in CWS

While Garnett et al. (2018) found structural differences in the gray matter in CWS compared to those who recover from stuttering and fluent peers, Chow and Chang (2017) studied white matter development. This study examined developmental trajectories of white matter in persistent and recovered CWS deviate from typically developing children. We hypothesized that FA reductions in the tracts identified in a recent meta-analysis (Neef, Anwander, & Friederici, 2015) based on previous DTI studies of persistent stuttering (i.e., arcuate fasciculus underlying frontoparietal regions and the body of the CC) are related to trait deficits of stuttering and hence would also be found in CWS. Moreover, we expected that, if the FA reductions in these tracts reflect underlying stuttering behavior, there would be continued anomalous FA development in the same areas in children with persistent stuttering.

Detailed methods can be seen in Chow and Chang (2017). In brief, 195 high-quality DTI scans from 35 stuttering children (22 boys, 13 girls; 12 recovered) and 43 controls (21 boys, 22 girls) were included. Participants' ages at the initial visit ranged from 3.2 to 10.7 years, with a mean age of 6.5 years and an SD of 2.1. The number of longitudinal scans acquired from each child ranged from one to four. Among these, 17 children (seven controls, five persistent, five recovered) provided a total of four scans that were useable for analysis, 24 children (13 controls, seven persistent, four recovered) provided a total of three scans that were useable for analysis, 19 children (14 controls, three persistent, two recovered) provided two scans that were useable for analysis, and 18 children (nine controls, eight persistent, one recovered) provided a single scan that was entered into the analysis.

DTI Data Analyses

One hundred ninety-five high-quality DTI scans (103 for controls, 55 for persistent, and 37 for recovered) were processed using Tortoise developed by the NIH Pediatric Neuroimaging Diffusion Tensor MRI Center (Pierpaoli et al., 2010). Individual FA maps were output, normalized to a standard space (ICBM152), and spatially smoothed with a 4-mm full width at half maximum Gaussian kernel. Group analysis of the normalized FA maps was carried out using a voxel-based approach in the white matter area, which was defined using the average FA across all participants. Voxels with average FA of less than 0.25 were excluded.

Linear mixed-effects modeling was employed to analyze group and age-related effects on FA, which is able to handle an unequal number of within-subject measurements and unbalanced longitudinal data (Bernal-Rusiel et al., 2013; Chen, Saad, Britton, Pine, & Cox, 2013). Our effects of interest included group (control, persistent, recovered) and Group × Age interactions. Socioeconomic status, IQ, sex, Group × Quadratic Age interactions, and the head motion measure were included to capture the potential nuisance effects. Model estimates were compared using t tests. False positives due to multiple voxelwise comparisons were controlled by the p value of each voxel and a spatial extent (cluster size) threshold (k), which was estimated using AFNI 3dClustSim (Version 17.2.13; http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/pub/dist/doc/program_help/3dClustSim.html). Unless otherwise specified, the thresholds were set at p < .01 and k > 33 voxels, corresponding to a corrected p value of .05.

Results

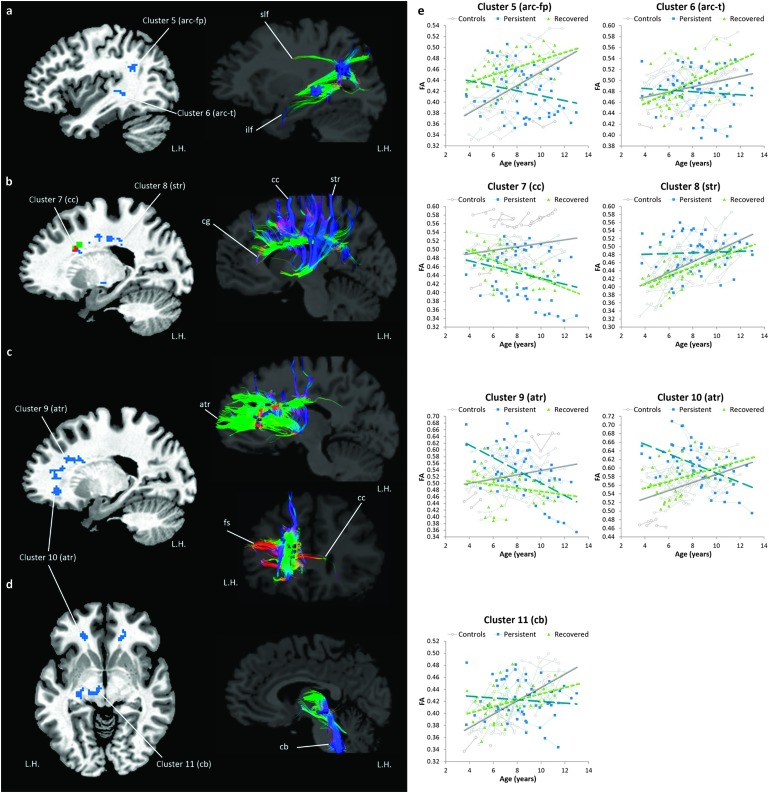

Relative to controls, both persistent and recovered groups exhibited overall FA reductions in the left arcuate fasciculus in the inferior parietal lobule (i.e., a part of the SLF) and in the posterior temporal lobe (see Figure 4a and scatter plots in Figure 4c). Moreover, the persistent group showed a reduction in the midsection of the CC body and splenium, whereas recovered children showed FA reductions in the superior part of the CC body, near the SMA (see Figures 4b and 4c).

Figure 4.

Overall fractional anisotropy (FA) reductions in children with persistent stuttering and children who recovered from stuttering relative to controls (group effect). (a, b) The left column shows the white matter areas where significant FA reductions were found in the persistent group (blue), the recovered group (green), and both groups (red). The right column illustrates the white matter fibers passing through the areas showing FA reductions based on DTI tractography of a 9-year-old female control participant. (c) Individual FA values in the clusters of FA reductions located in the left arcuate fasciculus and the mid body of the corpus callosum were plotted against age. White circles, blue squares, and green triangles indicate individual FA values in the control, persistent, and recovered groups, respectively. Data points of the same participant are connected by thin solid gray lines. Linear trend lines were added to illustrate the developmental trajectories of FA in each group (controls: gray line, persistent: blue dashed line, and recovered: green dotted line). arc-fp = arcuate fasciculus in the frontoparietal areas; arc-t = arcuate fasciculus in the temporal lobe; cc = corpus callosum; cg = cingulum; ilf = inferior longitudinal fasciculus; L.H. = left hemisphere. Reprinted from Chow and Chang (2017), “White Matter Developmental Trajectories Associated With Persistence and Recovery of Childhood Stuttering,” Human Brain Mapping, by permission of John Wiley and Sons. Copyright © 2017 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Regarding the age-related changes, the persistent group exhibited a lower FA growth rate in midline white matter structures, including the body of CC, cingulum, superior thalamic radiation (see Figures 5b and 5e), anterior thalamic radiation (see Figures 5c and 5e), and the cerebral and cerebellar peduncles (see Figures 5d and 5e). Lower FA growth rate in the body of CC and the anterior thalamic radiation was observed, but the spatial extent was much smaller than that exhibited by the persistent group (see Figures 5b and 5e). Unique to the recovered group, a lower FA growth rate was found in the right inferior longitudinal fasciculus (anterior temporal part) and the left dorsolateral frontal area when compared with controls (not shown). Compared with controls, a higher FA growth rate was found in the splenium of the CC for children with persistent stuttering, but a higher FA growth rate was observed in the body of CC near the SMA and the cerebellum for recovered children (not shown).

Figure 5.

Fractional anisotropy (FA) growth rate reduction in children with persistent stuttering and children who recovered from stuttering relative to controls (Group × Age interactions). (a–d) The left column shows the white matter areas where significant lower FA growth rates were found in the persistent group (blue), the recovered group (green), and both groups (red). The right column illustrates the white matter fibers passing through the areas showing reductions of FA growth rate based on diffusion tensor imaging tractography of a 9-year-old female control participant. (e) Individual FA values in the speech motor regions showing reductions of FA growth rate were plotted against age. White circles, blue squares, and green triangles indicate individual FA values in the control, persistent, and recovered groups, respectively. Data points of the same participant are connected by thin solid lines. Linear trend lines were added to illustrate the developmental trajectories of FA in each group (controls: gray line, persistent: blue dashed line, and recovered: green dotted line). arc-fp = arcuate fasciculus in the frontoparietal areas; arc-t = arcuate fasciculus in the temporal lobe; atr = anterior thalamic radiation; cb = cerebral peduncle; cc = corpus callosum; cg = cingulum; fs = frontal lobe short fibers; ilf = inferior longitudinal fasciculus; L.H. = left hemisphere; str = superior thalamic radiation. Reprinted from Chow and Chang (2017), “White Matter Developmental Trajectories Associated With Persistence and Recovery of Childhood Stuttering,” Human Brain Mapping, by permission of John Wiley and Sons. Copyright © 2017 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Summary of Study 2

Our results showed that the risk of stuttering, regardless of eventual persistence or recovery, was associated with overall FA reductions in parietal–temporal areas of the left arcuate fasciculus and the body of the CC. Since these differences were consistent across the age range of our samples (3–10 years of age at the initial visit), they were likely developed before the onset of stuttering symptoms. However, these anomalies may not necessarily lead to persistent stuttering if the white matter areas grow at the normal rate. In the case of recovered children, many of the regions with attenuated white matter integrity linked to stuttering showed normalized growth patterns with age. On the other hand, stuttering persistence was specifically associated with reduction of growth rate in white matter tracts interconnecting the left frontotemporal regions, bilateral motor areas, and the basal ganglia. These results suggest that normal (although delayed) developmental trajectories of white matter tracts in recovered children can eventually support fluent speech production, but a persisting anomalous developmental trajectory in children who continue to stutter. Further investigation is needed to understand the factors and mechanisms driving these developmental changes that may help develop treatment strategies to mitigate stuttering symptoms and enhance chances of recovery in CWS.

Discussion

Here, we reviewed two recent neuroanatomical studies associated with childhood stuttering and developmental trajectories differentiating persistent and recovery groups. One study focused on morphometric differences derived from surface-based measures of shape and size of cortical areas, and the other reported on measures reflecting microscopic structural changes in major white matter tracts. These two studies provide us with updated and more comprehensive insights into possible anomalous neuroanatomical development associated with childhood stuttering. As mentioned in the introduction, white and gray matter developments influence one another and relate to maturation of brain functions.

Although the goal of these studies was not to determine whether gray and white matter structural anomalies found in CWS are related to each other, the results in general do corroborate one another. For instance, both studies showed that structural anomalies associated with stuttering are concentrated in the left hemisphere. In particular, both studies seem to point to the left vPMC and mid-PMC as possible areas of core deficits in stuttering, as both cortical thickness and white matter connections between these motor areas and the pSTG are markedly reduced in persistent stuttering. Furthermore, we observed age-related changes in the cortical areas (SMA and pre-SMA) related to gyral anatomy associated with recovery, which may be related to a successful compensatory process. However, minimal changes in white matter were associated with recovery from stuttering. Taken together, our results indicate that cortical reorganization in pre-SMA/SMA, perhaps more than white matter compensatory growth involving these regions, may be more crucial for the recovery of stuttering. Examining white and gray matter findings together thus provides us better biomarkers that predict persistent stuttering.

Potential Neurological Underpinnings of Stuttering

According to recent models of speech motor control, production of fluent speech involves four major stages, each of which is associated with anatomical components of the speech motor network (Bohland, Bullock, & Guenther, 2010; Guenther, Ghosh, & Tourville, 2006; Hickok, 2012a, 2012b; Hickok & Poeppel, 2007; Houde & Nagarajan, 2011; Tourville & Guenther, 2011). In brief, the left STG is involved in the storage and activation of sound representations of upcoming speech. These sound representations need to be converted to motor representations via interactions between the STG and the speech motor areas including the IFG and the vPMC, as well as those between the IFG and the SMA. The motor representations are executed and controlled through the basal ganglia thalamocortical loop and the cortico-cerebellar loop. The “planned” motor representation and “actual” speech are continuously monitored and compared to the sound representations stored in the STG. Based on this simplified functional anatomical model, the results of our morphometric and DTI studies indicate that the core deficits of stuttering may exist within the conversion between sound and motor representations during speech production. This conversion may be affected by the reduction of structural integrity of the white matter tracts connecting the STG and the IFG/vPMC (Study 2) and the morphometric anomalies in vPMC (Study 1).

On the other hand, neither study found substantial structural differences between CWS and controls in temporal regions, suggesting that the process to activate and compare sound representations may be intact in CWS. Interestingly, structural anomalies in regions associated with “execution” of speech were observed in both of our studies. Specifically, the DTI study showed that persistence was associated with reduced FA with age in the cortical spinal tracts, while the morphometry study showed a nonsignificant age-related reduction of cortical thickness in the inferior motor areas that control articulator movements (vMC and aCO).

Developmental Trajectories Associated With Recovery From Stuttering

In both studies, we were interested in group effects and in any interaction with age that may reveal developmental trajectories that are characteristic of recovery. In Study 2, we conducted a linear mixed-effects analysis to enable longitudinal comparison of developmental trajectories (Chow & Chang, 2017). Children who would eventually recover from stuttering were found to exhibit aberrant FA reduction relative to controls in the left arcuate fasciculus and CC, but FA developmental trajectories in these areas are normal; that is, the rate of FA increases with age were comparable to that exhibited by controls (see Figures 5a and 5b). These results indicate a delay of white matter development that is common in CWS in general, which becomes “normalized” with age in children who ultimately recover from stuttering. In contrast, the persistent group exhibited age-related “decreases” rather than the expected “increases” in white matter integrity, as was shown by the control and recovered groups. However, it is not clear what caused the divergent white matter developmental trajectories in the recovery and persistent groups.

Our gray matter morphometric study may provide some insights into this issue (Garnett et al., 2018). In this study, we showed age-related changes in gyrification measures that differentiated the recovered and control groups. The recovered group exhibited a higher rate of gyrification reduction in the pre-SMA and SMA areas. Since the gyrification of these area is, in general, decreasing with age (see Figures 3e and 3f), higher rate of gyrification reduction indicates an earlier than normal maturation in the pre-SMA and SMA areas in the recovery group, which may play a role in compensating the core deficits associated with vPMC and vPMC–STG connections. This interpretation is speculative; however, the pre-SMA/SMA is connected with the left IFG/PMC areas via the frontal aslant tract (Dick, Bernal, & Tremblay, 2014), which has been implicated in language production (Catani et al., 2013). Through this connection, the developmental changes in pre-SMA and SMA with recovery may compensate the core deficits in the IFG/vPMC areas and contribute to achieving alleviation of stuttering and eventual recovery. Some support comes from negative correlations between gyrification and years of training when comparing expert versus novice divers (Guenther, 2016; Zhang et al., 2016), suggesting that reduced gyrification contributes to the development of specific skills and behaviors. In our data, developmental changes in pre-SMA/SMA gyrification were only seen in the recovered group but not in the persistent group and, therefore, are unlikely to be related to the cause of stuttering. Instead, a decrease in gyrification with age in the recovery group suggests that changes in the left SMA/pre-SMA function and/or structure may somehow offset the neural processing impairments that caused these children to stutter when they were younger. These ideas should be confirmed in future studies.

Caveats

Some limitations of the studies include the wide age range of participants and the possibility of later recovery and/or relapse to persistence in children after the period of research participation. Research suggests that most children begin to stutter between 2 and 6 years of age, and recovery occurs in most cases within 36 months after onset (e.g., Conture, 2001; Yairi & Ambrose, 1999). Children past the age of natural recovery were included in both studies reported here; however, with objective speech samples, disfluency analysis, and parental reports, we were able to document their stuttering starting when they were younger.

Thus, although the age range of our participants includes older children who are well past the most commonly reported age of recovery, our recovered cases nevertheless were those with documented stuttering and recovery history that we were able to capture during the course of our longitudinal study. Because we allowed a larger age range in this cohort of participants, this is reflected in the small number of recovered cases that were included in the two studies. Our second wave of recruitment is ongoing and is focusing on a much tighter age range, with initial visits occurring when the children are between 3 and 5 years of age.

Children who begin to stutter recover at similar rates irrespective of whether they had therapy, as was summarized in Franken, Koenraads, Holtmaat, and van der Schroeff (2018): children who did not receive therapy (74%–80%) versus those who did have therapy (65%–82%). It is possible that the oldest children in this data set received more treatment in the past, potentially for longer periods than in younger children. In Study 1, of the four children who entered the study at 9+ years of age, two received previous fluency therapy, both for approximately 4 years. Given that this is a very small subgroup, we do not expect that it contributed significantly to our findings. Furthermore, we conducted an additional analysis with therapy history as a covariate and found that this did not change any of our results: Namely, approximately 30% of our pool of CWS report having had or is currently enrolled in therapy, with all receiving nonintensive behavioral therapy (e.g., 30 min/week). Our analyses treating therapy history as a covariate in our structural data analyses indicated no significant effects of therapy, possibly due to the nonintensive nature of the interventions (p = .803). In the data set for Study 1, 12 (33%) of the children who entered the study had fluency treatment prior to or at the time of enrollment. Of those 12, 10 children had at least two visits (thus were followed for at least 12 months) and were considered persistent at their final visit. It would be interesting to explore if the results from the anatomical analyses differ between children who recovered naturally compared to children who recovered due to (at least in part) fluency therapy.

The determination of persistence versus recovery was based on the repeated fluency assessments on subsequent visits, providing us with the ability to reassess and potentially revise this determination at later visits. Most children had at least two additional visits after Visit 1, and we are confident in our group assignment. Although it is unlikely that a change in status could occur more than 4 years after stuttering onset, it is possible that some children from the recovered group could show relapse or that some children may still recover from stuttering. Consequently, we continue to monitor these children to confirm group assignment in the future.

Conclusions

The two neuroanatomical studies of childhood stuttering reviewed in this article point to gray and white matter MRI indices that differentiate CWS from controls. Furthermore, examining age-related changes in these indices in children who eventually persisted or recovered in stuttering led to novel discoveries of distinct developmental trajectories that provide first clues to the neural mechanisms of childhood stuttering persistence and recovery. The results point to possible core deficits in structural connectivity among left hemisphere speech motor and sensory regions that are delayed but normalized with age in recovered children. Persistent stuttering is associated with continued anomalies in cortical speech motor areas and their white matter connections and additional changes to white matter tracts that form circuits among cortical, subcortical, and cerebellar areas.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Awards R01DC011277 (S. C.) and R21DC015312 (S. C.) from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders and the Matthew K. Smith Stuttering Research Fund. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders or the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank all the children and parents who have participated in this study. The authors also thank David Zhu for his support on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning protocols; Kristin Hicks; Saralyn Rubsam; Megan Sheppard for her assistance in participant recruitment, behavioral testing, and help with MRI data collection; Scarlett Doyle for her assistance in MRI data acquisition; Barbara Holland for assistance with data quality control; and Ashley Diener for her assistance in speech data analyses.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by Awards R01DC011277 (S. C.) and R21DC015312 (S. C.) from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders and the Matthew K. Smith Stuttering Research Fund. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders or the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank all the children and parents who have participated in this study.

References

- Barnea-Goraly N., Menon V., Eckert M., Tamm L., Bammer R., Karchemskiy A., … Reiss A. L. (2005). White matter development during childhood and adolescence: A cross-sectional diffusion tensor imaging study. Cerebral Cortex, 15, 1848–1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal D. S., Gracco V. L., Brettschneider J., Kroll R. M., & De Nil L. F. (2013). A voxel-based morphometry (VBM) analysis of regional grey and white matter volume abnormalities within the speech production network of children who stutter. Cortex, 49(8), 2151–2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal-Rusiel J. L., Greve D. N., Reuter M., Fischl B., Sabuncu M. R., & Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. (2013). Statistical analysis of longitudinal neuroimage data with linear mixed effects models. NeuroImage, 66, 249–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohland J. W., Bullock D., & Guenther F. H. (2010). Neural representations and mechanisms for the performance of simple speech sequences. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 22(7), 1504–1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody B. A., Kinney H. C., Kloman A. S., & Gilles F. H. (1987). Sequence of central nervous system myelination in human infancy. I. An autopsy study of myelination. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology, 46, 283–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catani M., Mesulam M. M., Jakobsen E., Malik F., Martersteck A., Wieneke C., … Rogalski E. (2013). A novel frontal pathway underlies verbal fluency in primary progressive aphasia. Brain, 136(8), 2619–2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S. E., Angstadt M., Chow H. M., Etchell A. C., Garnett E. O., Choo A. L., … Sripada C. (2018). Anomalous network architecture of the resting brain in children who stutter. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 55, 46–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S. E., Erickson K. I., Ambrose N. G., Hasegawa-Johnson M. A., & Ludlow C. L. (2008). Brain anatomy differences in childhood stuttering. NeuroImage, 39(3), 1333–1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S. E., & Zhu D. C. (2013). Neural network connectivity differences in children who stutter. Brain, 136(Pt. 12), 3709–3726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S. E., Zhu D. C., Choo A. L., & Angstadt M. (2015). White matter neuroanatomical differences in young children who stutter. Brain, 138(Pt. 3), 694–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G., Saad Z. S., Britton J. C., Pine D. S., & Cox R. W. (2013). Linear mixed-effects modeling approach to fMRI group analysis. NeuroImage, 73, 176–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow H. M., & Chang S. E. (2017). White matter developmental trajectories associated with persistence and recovery of childhood stuttering. Human Brain Mapping, 38(7), 3345–3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conture E. G. (2001). Stuttering: Its nature, diagnosis, and treatment. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Dale A. M., Fischl B., & Sereno M. I. (1999). Cortical surface-based analysis: I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. NeuroImage, 9(2), 179–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick A. S., Bernal B., & Tremblay P. (2013). The language connectome new pathways, new concepts. Neuroscientist, 20(5), 453–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franken M. J. P., Koenraads S. P. C., Holtmaat C. E. M., & van der Schroeff M. P. (2018). Recovery from stuttering in preschool-age children: 9 Year outcomes in a clinical population. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 58, 35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrichs-Maeder C. L., Griffa A., Schneider J., Hüppi P. S., Truttmann A., & Hagmann P. (2017). Exploring the role of white matter connectivity in cortex maturation. PLOS ONE, 12(5), e0177466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnett E. O., Chow H. M., Nieto-Castañón A., Tourville J. A., Guenther F. H., & Chang S.-E. (2018). Anomalous morphology in left hemisphere motor and premotor cortex of children who stutter. Brain, 141, 2670–2684. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awy199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard N., Raybaud C., & du Lac P. (1991). MRI study of brain myelination. Journal of Neuroradiology, 18, 291–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogtay N., Giedd J. N., Lusk L., Hayashi K. M., Greenstein D., Vaituzis A. C., … Thompson P. M. (2004). Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(21), 8174–8179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther F. H. (2006). Cortical interactions underlying the production of speech sounds. Journal of Communication Disorders, 39(5), 350–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther F. H. (2016). Neural control of speech. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guenther F. H., Ghosh S. S., & Tourville J. A. (2006). Neural modeling and imaging of the cortical interactions underlying syllable production. Brain and Language, 96(3), 280–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickok G. (2012a). Computational neuroanatomy of speech production. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(2), 135–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickok G. (2012b). The cortical organization of speech processing: Feedback control and predictive coding the context of a dual-stream model. Journal of Communication Disorders, 45(6), 393–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickok G., & Poeppel D. (2007). The cortical organization of speech processing. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 8(5), 393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houde J. F., & Nagarajan S. S. (2011). Speech production as state feedback control. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 5, 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bihan D., & Johansen-Berg H. (2012). Diffusion MRI at 25: Exploring brain tissue structure and function. NeuroImage, 61(2), 324–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M. (1969). Frog, where are you? New York, NY: Penguin Putnam. [Google Scholar]

- Neef N. E., Anwander A., & Friederici A. D. (2015). The neurobiological grounding of persistent stuttering: From structure to function. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports, 15(9), 63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto-Castanon A., Ghosh S. S., Tourville J. A., & Guenther F. H. (2003). Region of interest based analysis of functional imaging data. NeuroImage, 19(4), 1303–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T., Collins D. L., Evans A. C., Leonard G., Pike B., & Zijdenbos A. (2001). Maturation of white matter in the human brain: A review of magnetic resonance studies. Brain Research Bulletin, 54, 255–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierpaoli C., Walker L., Irfanoglu M. O., Barnett A., Basser P. J., Chang L.-C., … Wu M. (2010). TORTOISE: An integrated software package for processing of diffusion MRI data. Proceedings of the ISMRM 18th Annual Meeting, 2010, 1597. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J. C. (2005). Linear mixed effects models for longitudinal data. In Armitage P. & Colton T. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of biostatistics. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Riley G. D., & Bakker K. (2009). Stuttering Severity Instrument–Fourth Edition: SSI-4. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer M., Koch M. A., Paulus W., Weiller C., & Büchel C. (2002). Disconnection of speech-relevant brain areas in persistent developmental stuttering. The Lancet, 360(9330), 380–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stejskal E. O., & Tanner J. E. (1965). Spin diffusion measurements: Spin echoes in the presence of a time-dependent field gradient. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 42, 288–292. [Google Scholar]

- Tau G. Z., & Peterson B. S. (2010). Normal development of brain circuits. Neuropsychopharmacology, 35(1), 147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourville J. A., & Guenther F. H. (2011). The DIVA model: A neural theory of speech acquisition and production. Language and Cognitive Processes, 26(7), 952–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourville J. A., & Guenther F. H. (2012). Automatic cortical labeling system for neuroimaging studies of normal and disordered speech. In Society for Neuroscience–Abstracts (Vol. 38, No. 681.06). [Google Scholar]

- Walsh B., Tian F., Tourville J. A., Yücel M. A., Kuczek T., & Bostian A. J. (2017). Hemodynamics of speech production: An fNIRS investigation of children who stutter. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 4034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yairi E., & Ambrose N. (1999). Early childhood stuttering I: Persistency and recovery rates. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 42(5), 1097–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yairi E., & Ambrose N. (2013). Epidemiology of stuttering: 21st Century advances. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 38(2), 66–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yairi E., Ambrose N., & Cox N. (1996). Genetics of stuttering: A critical review. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 39(4), 771–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Zhao L., Bi W., Wang Y., Wei G., Evans A., & Jiang T. (2016). Effects of long-term diving training on cortical gyrification. Scientific Reports, 6, 28243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]