Abstract

Background

Speech impairment, which reduces Quality of Life (QOL), frequently occurs in individuals with Parkinson's disease (PD). As speaking is required for social interaction, speech impairment can reduce one's life satisfaction. Although QOL has been well-studied in individuals with PD, the QOL of their caregivers has seldom been investigated. This study compared the QOL of individuals with PD and their caregivers. The relationships between QOL, self-rated speech scale, and life satisfaction level were examined.

Method

A total of 20 individuals with PD and their caregivers completed the Parkinson's disease Questionnaire-39 (PDQ-39) scale and the Life Satisfaction Scale (LSS). In addition, PD participants were asked to complete the Self-Rated Speech Scale (SRSS) to rate their speech intelligibility.

Result

PD participants reported significantly lower QOL scores than their caregivers. However, there was no difference between the two groups on the social support and stigma dimensions, indicating that both groups reported similar levels of social support and stigma in their daily lives. A moderate significant correlation was observed between the LSS and PDQ-39 scores in the PD group, suggesting that life satisfaction could affect their QOL. Moreover, moderate correlation was found between the LSS and SRSS, showing that participants self-reported speech intelligibility has an impact on their life satisfaction.

Conclusion

In general, individuals with PD showed lower QOL than their caregivers. Given that the SRSS, LSS and QOL are moderately correlated, identifying patients' perception on their speech intelligibility and life satisfaction could help clinicians to better understand their patients' needs when delivering speech therapy services.

Keywords: Parkinson's disease, quality of life, caregiver, communication, questionnaire

Introduction

Quality of Life (QOL) refers to one's perceptions of his/hers experiences in life, and it has been widely used as a measurement outcome in clinical and research settings. While the QOL of individuals with Parkinson's Disease (PD) has been well studied, the QOL of their caregivers has seldom been invetigated. As it is stressful to care for an individual with PD, it is expected that the personal life and QOL of the caregivers will be influenced (1,2).

Caretaking is an all-day job, depending on the degree of impairment of the individuals with PD; the demands for help increases as the disease advances. Caregivers play an important role as they assist individuals with PD with such matters as the activities of daily living (ADLs), medication and medical management, household chores, financial management, transportation, social and emotional support and decision making regarding medication (2,3). As the disease progresses, individuals with PD require more and more assistance from others (4). Previous studies have reported that 56% of individuals with PD required assistance one year after diagnosis. Approximately 88.9% of the caregivers are spouses, while 5.9% are adult children (3,4). As the spouses and adult children provide increasing amount of care and even withdraw from their own personal lives, they face high degrees of stress (5,6). Moreover, the caregivers of PD patients experience greater mental stress than physical stress (7). As the patient's health deteriorates, the caregivers' burdens increase, affecting their QOL (8,9). A reduction of the caregivers' QOL can result in a reduction in the quality of care (6,10).

Quality of life of caregivers is important, as the resulted burden, overwhelmed caring capacity or reduction of QOL of caregiver could lead to long term institutionalization of individuals with PD, or consequences of physical or mental health of caregivers (6,10). In addition, quality of care provided to individuals with PD will also be affected. Thus, investigating dimensions in QOL of caregivers is important to enable rehabilitation therapy to be targeted to assist both individuals with PD and caregivers in order to reduce factors leading to poor QOL.

Person-centeredness: The philosophy that underlies care and service delivery among allied healthcare disciplines is focusing on meeting an individual's needs or values, and optimizing the individual's experiences with care and focusing on the family as the centre of decision-making (11). The meaning and practice of person-centredness is unique in rehabilitation contexts. For instance, rehabilitation requires the active participation of patients and their families (often the main caregiver) rather than just adherence to medication prescriptions (12). Such rehabilitation, when treating a patient with PD, often takes place over a long period of time. During speech therapy, patient participation can be challenged by the presence of communication impairment. This occurs in as many as 89% of individuals with PD (13). Moreover, family involvement is a priority during speech therapy as the ‘client’ is not just the patient with PD; it also includes the patient's family. Hence, understanding the limitations on a patient's QOL is inadequate when providing quality service. The caregiver's QOL should also be considered to understand better the patient's and the caregiver's perspectives on goals and/or disability in the planning of effective rehabilitation therapy (14).

Communication is a need for social interaction. As the PD progresses, the patient's speech intelligibility is reduced (15). In fact, patients with PD often present with a communication disorder known as dysarthria, resulting in poor speech production and can lead to a reduction in QOL(16). When the patient lacks speech clarity, he/she reduces participation in daily social events (17). Presently, speech therapists often overlook the patient's QOL during therapeutic management because of lack of understanding of the relationship between communication and QOL (14). Therefore, understanding the communication difficulties experienced by patients with PD is crucial for speech therapists when assessing and planning effective intervention to improve QOL (18,19,20). Although speech and language therapy have been practiced in Malaysia for over 20 years, there has been no research conducted on the relationship between QOL and communication of individuals with PD and their caregivers.

According to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, speech-language therapists should address communication skills of patients to increase their quality of life (18). However, quality of life is often overlooked by speech-language pathologists, due to the absent of conceptual relationship between communication and quality of life (14). While QOL helps evaluate an individual's life experiences, the individual's satisfaction towards life may be measured by the life satisfaction scale, a subjective measure that focuses on one's perspectives on life as a whole (21). To date, there is limited research which examines the life satisfaction levels of PD patients and their caregivers. Given that communication could negatively impact one's QOL and life satisfaction level, it is necessary for speechlanguage therapists to understand the communicative difficulties experienced by these individuals, in assessing and planning effective intervention to achieve the rehabilitative goals. Hence, this study had three aims. Its primary aim was to determine the differences in QOL of PD patients and their caregivers. The secondary aim was to determine the relationships between QOL and life satisfaction among PD patients and their caregivers. The third aim was to examine the relationships between QOL, life satisfaction, and self-perception of speech among PD patients.

Methods

Participants: A total of 20 individuals with PD and 20 caregivers participated in this study. Of the 20 caregivers, 14 were spouses of individuals with PD, three were their children, one was neighbor, and two were maids. This number of subjects was calculated using the power analysis for t-test in GPower program to determine a sufficient sample size using an alpha of 0.05, power of 0.97, a large effect size (w=0.8). All participants (including the main caregivers) were active members of the Malaysia Parkinson's Disease Association (MPDA). Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia's Board of Ethics. All participants provided informed consent before participating in the study.

Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39): The Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ- 39) (22) was used to compare the quality of life of individuals with PD and the control across eight dimensions: mobility (10 items), activities of daily living (6 items), emotional well-being (6 items), stigma (4 items), social support (3 items), cognitions (4 items), communication (3 items), and bodily discomfort (3 items). This survey was comprised of 39 items, presented in Likert scale (0 = never, 1 = occasionally, 2 =sometimes, 3 = often, 4 = always). Each dimension score was calculated and the total score was computed into the PD Summary Index Score (PDSI). A lower PDSI score indicates a better quality of life and vice versa. The PDQ-39 has been tested for validity and reliability (23), with a satisfactory level of internal consistency, content and convergent validity, and stability (24,25).

Life Satisfaction Scale (LSS): The LSS is a measure of self-reflection as it looks into an individual's satisfaction level towards life. The LSS is a 10-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating “Excellent”, and 10 indicating “Worst”. Individuals with PD and their caregivers were requested to measure their level of life satisfaction on the scale “before” and “after” being diagnosed with PD/or taking care of the individuals. The sample instruction was “Grade your life satisfaction AFTER you have Parkinson's disease”. For caregivers, they were instructed as “Grade your life satisfaction AFTER you began taking care of the individual with Parkinson's disease.”

Self-rated Speech Scale (SRSS): The SRSS is a self-reflection measure on speech intelligibility, with a 10-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating “Excellent”, and 10 indicating “Worst”. Only individuals with PD were asked to fill-in this scale. They were asked to judge their speech “before” and “after” they had PD (“Grade your speech AFTER having Parkinson's disease”).

Procedure: A survey package with information sheet, consent form, demographic sheet, and PDQ-39, LSS and SRSS was distributed to each participant face-to-face. The PD participants were asked to complete the survey based on their latest one-month experience with having PD, whereas the caregivers were requested to complete the questionnaire that reflects on their daily experiences.

Data analysis: Descriptive statistic for the demographic information was calculated for both groups. Independent t-test was conducted given that data were normally distributed for both PD [Shapiro-Wilk W (20) =.951, p= .388], and caregiver [Shapiro-Wilk W (20) =.929, p= .148]. The three items (“Had difficulty with your speech?”, “Felt unable to communicate with people properly?”, “Felt ignored by people?”) that examined the sommunication dimension in the PDQ-39 form was compared between groups using t-test.

Additionally, the Pearson correlation was conducted between the PDQ-39 total score (also known as PDQSI score) and Life Satisfaction Scale (LSS) for PD and caregiver groups. Additionally, Pearson correlation of Self-Rated Speech Scale (SRSS) with Life Satisfaction Scale (LSS) and the Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire Summary Index (PDQSI) for PD group were also conducted.

Results

Demographic data: Table 1 shows the demographic data of all participants. PD participants ranged in age from 54 to 82 years (Mean=68.70, SD=7.01). Of them, 11(55.00%) were males, and 9 were females (45.00%). For caregivers, the age ranged from 35 to 81 (Mean=60.30, SD=13.78), with 7 females (35.00%) and 13 males (65.00%). An independent t-test showed significant difference in age between the PD and caregiver groups, t (38) = 2.370, p < .05. Additionally, non-significant difference was found in gender between groups, t (1) = 1.616, p = .204. As expected, a significantly higher number of participants were unemployed in both groups [PD= 95% unemployed, caregivers= 75% unemployed), X2(1) = 3.14, p =.08].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics for 20 individuals with Parkinson's disease and 20 caregiver

| PD | Controls | p-value | |

|

Age (Years) Mean (SD) Range |

68.70 (7.01) 54 – 82 |

60.30 (13.78) 35 - 81 |

t (38) = 2.37 p < .05 |

|

Gender Male Female |

11 (55.00%) 9 (45.00%) |

7 (35.00%) 13 (65.00%) |

t (1) = 1.62 p = .204 |

|

Employment Status Employed Unemployed |

1 (5.00 %) 19 (95.00%) |

5 (25.00%)* 15 (75.00%) |

t (1) = 3.14 p = 0.077 |

|

Years Diagnosed with PD Mean (SD) Range |

6.9 (19.39) 1–16 |

- | - |

including the 2 maids as caregivers

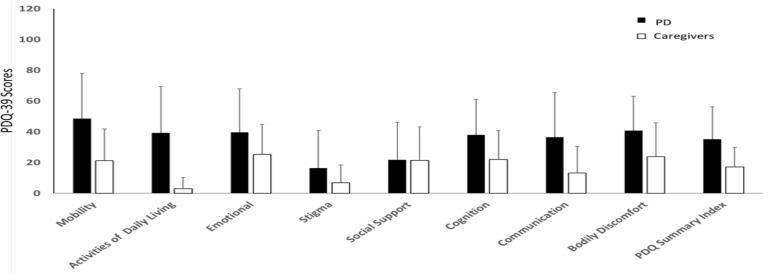

PDQ-39: Overall, the Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire Summary Index (PDSI) mean scores for the PD group (Mean= 35.11; SE= 3.90) were higher than the caregiver group (Mean=17.07; SE= 2.24), suggesting that the PD group had poorer level of quality of life. With independent t-test, all the dimensions in the PDQ-39 were significantly different between groups, except the stigma (t= 2.00, p= 0.50) and the social support dimensions (t= 0.064, p= 0.95) (Table 2). The dimension with greatest mean difference was the activities of daily living, whereby individuals with PD had higher mean scores (Mean = 39.22, SE= 5.60) than caregivers (Mean= 2.90, SE= 1.29) (Figure 1). On the other hand, social support had the least mean difference; individuals with PD reported higher mean score (Mean = 21.84, SE=4.50) than the caregivers (Mean= 21.46, SE=3.77). Additionally, the three items (“Had difficulty with your speech?”, “Felt ignored by people?”, “Felt unable to communicate with people properly?”) that examined the communication dimension in the PDQ-39 scale were compared between groups (Table 3). Two items (“Had difficulty with your speech?”, “Felt ignored by people?”) showed significant differences in perception towards communication (p< .05), with higher average score from the individuals with PD.

Table 2.

Dimensional difference between PD and Caregivers using Independent t-test

| Dimensions | t | p-value | Effect Size |

Mean Difference |

Std. Error Difference |

95% Confidence Interval of the Difference |

|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Mobility | 4.28 | .000 | 1.08 | 27.40 | 6.40 | 14.59 | 40.20 |

| Activities of daily living |

6.70 | .000 | 1.65 | 36.32 | 5.42 | 25.48 | 47.16 |

| Emotional | 2.34 | .023 | 0.59 | 14.28 | 6.11 | 2.05 | 26.51 |

| Stigma | 2.00 | .050 | 0.50 | 9.56 | 4.78 | .00 | 19.12 |

| Social support | .06 | .949 | 0.02 | 0.37 | 5.83 | −11.28 | 12.03 |

| Cognition | 3.00 | .004 | 0.76 | 15.96 | 5.32 | 5.33 | 26.60 |

| Communication | 3.90 | .000 | 0.98 | 23.36 | 5.99 | 11.38 | 35.35 |

| Bodily discomfort |

3.03 | .004 | 0.77 | 17.07 | 5.63 | 5.80 | 28.33 |

| PDQSI | 4.13 | .000 | 1.04 | 18.04 | 4.37 | 9.30 | 26.78 |

Figure 1.

PDQ-39 Scores for each dimension of both PD and caregivers

Table 3.

Comparison of communication dimensions between PD and caregiver groups

| Communication items |

t | p-value | Effect Size |

Mean Difference |

Std. Error Difference |

95% Confidence Interval of the Difference |

|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Had difficulty with your speech? |

6.16 | .000* | 1.54 | 1.49 | .24 | 1.00 | 1.97 |

| Felt ignored by people? |

2.62 | .011* | 0.66 | .74 | .28 | .18 | 1.31 |

| Felt unable to communicate with people properly? |

1.95 | .06 | 0.49 | .58 | .30 | -.02 | 1.17 |

Correlation between Life Satisfaction Scale (LSS), Self-rated Speech Scale (SRSS) and PDQSI: Pearson correlation coefficient (r) is tabulated in Table 4. The Life Satisfaction Scale (LSS) showed a significant correlation with the PDQSI score for both groups, with moderate correlation of r(29)= .59, p<.001 for the PD group, whereas moderate correlation of r(33)= .46, p<.05 for the caregiver group. In addition, there was a moderate correlation when the Self-rated Speech Scale (SRSS) was correlated with Life Satisfaction Scale (LSS) r(29)= .57, p<.001; and PDQSI r(29)=.52, p<.05 in the PD group (Table 5). Strong correlation was over 0.60, a moderate correlation between 0.30 and 0.60, and low correlation was below 0.30 (26).

Table 4.

Correlation of PDQSI score with Life Satisfaction Scale for both PD and caregiver

| PDQSI score Correlate with | Pearson Correlation (r) | |

|

Life Satisfaction Scale (LSS) |

PD | 0.59** |

| Caregiver | 0.46* |

significant at 0.05 (2-tailed)

significant at 0.001 (2-tailed)

Table 5.

Correlation of Self-Rated Speech Scale (SRSS) with Life Satisfaction Scale (LSS) PDQSI score for the PD group

| Self-rated Speech Scale (SRSS) Correlate with |

Pearson Correlation ( r ) |

| Life Satisfaction Scale (LSS) | .57** |

| PDQSI score | .52* |

significant at 0.05 (2-tailed)

significant at 0.001 (2-tailed).

Discussion

To the best of authors knowledge, this is the first study of QOL in relation to the Life Satisfaction and Self-Rated Speech Scales of patients with PD in comparison with their caregivers in Malaysia. Consistent with previous studies, our findings show that individuals with PD experience lower quality of life compared to their caregivers (1,27,28). Specifically, individuals with PD showed more issues with mobility, activities of daily living, emotions, cognition, communication and bodily discomfort as reported in the PDQ-39. While our finding showed no group difference in the stigma and social support dimensions, one study found that the stigma experienced by PD patients impacted their caregivers (29). It would be worthwhile to examine the issue of stigma and other burdens experienced by caregivers in further studies. The lack of stigma and social support difference between the PD group and their caregivers may be because all participants were recruited from a support group. It could be that participation in a support group improves social support and social network, whereby patients and their caregivers would have greater acceptance of the disease and cope better with their difficulties in life (30,31,32). Future studies should examine whether support group participants improve one's social support and quality of life.

Speech impairment due to PD often leads to communication difficulties. It also affects one's participation in life and one's quality of life (33). This was supported by our findings that individuals with PD struggled more with communication issues than the caregiver group. In particular, PD participants felt that they “had difficulty with their speech” and “felt ignored by people” as reflected in the PDQ-39 scale. This indicates that PD participants faced barriers when communicating with others due to their disease. In fact, they were aware of such issues. Speech-language therapists could use PDQ-39 scales to examine their client's QOL and communication components when planning intervention.

While a moderate correlation between LSS and PDSI scores was found in the caregiver group, a moderate correlation between the LSS and PDSI scores was found in the PD group, indicating that life satisfaction could affect their quality of life. Similarly, a moderate correlation between life satisfaction (LSS) and self-rated speech scale indicated that participants who perceived their own speech as impaired showed lower life satisfaction. Given that communication difficulties affect QOL, clinicians should educate patients to rate their speech to meet the patient's needs, regarding their speech intelligibility expectations. Future studies should include both subjective and objective speech measurements that could provide more clinical data in assessing the relationship between speech intelligibility and QOL in this population. This could guide the clinicians to better understanding their client's needs in providing speech treatment to increase their QOL. Additionally, when asked to fill in the life-satisfaction scale, most of the participants commented that their life-satisfaction level was greatly affected by their medication, signifying that the effects of medication impact these patients' quality of life significantly (34). Future studies should examine the QOL before and after medication in PD population.

The results reported in this study do not reflect the PD group's quality of life levels at medication OFF stage (medication is wearing off and symptoms become poorly controlled) but with a small number of subjects. This was because most of the PD patients in this support group were at an early stage of PD and hence were still able to do their daily activities. We noticed a trend of caregiving changes in Malaysia, whereby maids from Indonesia or Philippines were becoming the primary caregivers, instead of family members (35). Due to language barrier and lower education level, most of the maids were unable to read or understand our surveys; they were excluded from this study. Only two maids were able to understand our survey and included into this study. Hence, the number of subjects in this study was limited. Given the small number of subjects, one should be cautious when interpreting the results of this study in that it only applied to those caregivers in a support group.

In sum, this study shows that PD patients have lower quality of life than their caregivers. Additionally, medication responsiveness could be one of the factors that influence life satisfaction and the QOL. Given that the SRSS and quality of life are moderately correlated, identifying patients' perception on their speech intelligibility can help clinicians better understand their patients' needs during speech therapy. Future studies should examine the effects of medication, SRSS and LSS on the quality of life of PD patients to ensure delivery of high quality care.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the UKM Young Researcher Research Grant GGPM-2016-070 (second author). The authors wish to thank all the participants for taking part in this study.

References

- 1.Scheife RT, Schumock GT, Burstein A, et al. Impact of Parkinson's disease and its pharmacologic treatment on quality of life and economic outcomes. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2000;57(10):953–962. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/57.10.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demeulemeester F, De Letter M, Miatton M, Santens P. Quality of life in patients with PD and their caregiving spouses: A view from both sides. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 2015;139:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2015.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peters M. Quality of Life and Burden in Caregivers for Patients with PD. Focus on Parkinson's Disease. 2014;24(1):44–48. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong SL, Gilmour H, Ramage-Morin PL. Parkinson's disease: Prevalence, diagnosis and impact. Health Reports. 2014;25(11):10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Reilly F, Finnan F, Allwright S, Smith GD, Ben-Shlomo Y. The effects of caring for a spouse with Parkinson's disease on social, psychological and physical well-being. British Journal of General Practice. 1996;46(410):507–512. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martínez-Martín P, Benito-León J, Alonso F, et al. Quality of life of caregivers in Parkinson's disease. Quality of Life Research. 2005;14(2):463–472. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-6253-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roland KP, Jenkins ME, Johnson AM. An exploration of the burden experienced by spousal caregivers of individuals with Parkinson's disease. Movement Disorders. 2010;25(2):189. doi: 10.1002/mds.22939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martínez-Martín P, Forjaz MJ, Frades-Payo B. Caregiver burden in Parkinson's disease. Movement Disorders. 2007;22(7):924. doi: 10.1002/mds.21355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez-Martin P, Arroyo S, Rojo-Abuin JM, et al. Burden, perceived health status, and mood among caregivers of Parkinson's disease patients. Movement Disorders. 2008;23(12):1673–1680. doi: 10.1002/mds.22106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azmin S, Khairul Anuar AM, Tan HJ. Nonmotor symptoms in a Malaysian Parkinson's disease population. Parkinson's Disease. 2014:472–157. doi: 10.1155/2014/472157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins A. Measuring what really matters: towards a coherent measurement system to support person-centred care. London: Health Foundation; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bright FA, Kayes NM, Worrall L, et al. A conceptual review of engagement in healthcare and rehabilitation. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2015;37:643–654. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2014.933899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sapir S, Pawlas AA, Ramig LO, et al. Voice and speech abnormalities in Parkinson disease: Relation to severity of motor impairment, duration of disease, medication, depression, gender, and age. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology. 2001;9:213–226. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cruice M. The contribution and impact of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health on quality of life in communication disorders. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2008;10(1–2):38. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sapir Shimon, Ramig Lorraine O, Fox Cynthia M. Intensive voice treatment in Parkinson's disease: Lee Silverman Voice Treatment. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2011;11(6):815–830. doi: 10.1586/ern.11.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duffy JR. Motor Speech Disorders: Substrates, Differential Diagnosis, and Management. United States of America: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartelius L, Elmberg M, Holm R, Lövberg AS, Nikolaidis S. Living with dysarthria: evaluation of a self-report questionnaire. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica. 2008;60(1):11–19. doi: 10.1159/000111799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, author. Scope of Practice in Speech Language Pathology. 2016. Aug 8, http://www.asha.org/policy.

- 19.Lubinski R, Hudson M W. Professional issues in speech-language pathology and audiology. New York: Cengage Learning; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Theodoros D G, Ramig L O. Communication and swallowing in Parkinson disease. San Diego: Plural Pub; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49:71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R, Peto V, Dummett S, Morley D, Saunders P. The Parkinson's disease questionnaire. Health Services Research Unit. Oxford: Joshua Horgan Print Partnership; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinez-Martin P, Jeukens-Visser M, Lyons KE, et al. Health-related quality-of-life scales in Parkinson's disease: critique and recommendations. Movement Disorders. 2011;26(13):2371–2380. doi: 10.1002/mds.23834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Damiano AM, McGrath MM, Willian MK, et al. Evaluation of a measurement strategy for Parkinson's disease: assessing patient healthrelated quality of life. Quality of Life Research. 2000;9(1):87–100. doi: 10.1023/a:1008928321652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick RAY, Peto VIV, Greenhall R, Hyman N. The Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39): development and validation of a Parkinson's disease summary index score. Age and ageing. 1997;26(5):353–357. doi: 10.1093/ageing/26.5.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hinkle DE, Wiersma W, Jurs SG. Applied Statistics for The Behavioral Sciences. fifth Houghton Mifflin; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Uem JM, Marinus J, Canning C, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease—a systematic review based on the ICF model. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2011;61:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peters M, Fitzpatrick R, Doll H, Playford D, Jenkinson C. Does self-reported well-being of patients with Parkinson's disease influence caregiver strain and quality of life? Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 2011;17(5):348–352. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajiah K, Maharajan MK, Yeen SJ, et al. Quality of life and caregivers' burden of Parkinson's disease. Neuroepidemiology. 2017;48:131–137. doi: 10.1159/000479031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Uden-Kraan CF, Drossaert CH, Taal E, Shaw BR, Seydel ER, van de Laar MA. Empowering processes and outcomes of participation in online support groups for patients with breast cancer, arthritis, or fibromyalgia. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18(3):405–417. doi: 10.1177/1049732307313429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barak A, Boniel-Nissim M, Suler J. Fostering empowerment in online support groups. Computers in Human Behavior. 2008;24(5):1867–1883. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Charlton GS, Barrow CJ. Coping and self-help group membership in Parkinson's disease: an exploratory qualitative study. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2002;10(6):472–478. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2002.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takahashi K, Kamide N, Suzuki M, et al. Quality of life in people with Parkinson's disease: the relevance of social relationships and communication. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2016;28(2):541–546. doi: 10.1589/jpts.28.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rahman S, Griffin HJ, Quinn NP, Jahanshahi M. Quality of life in Parkinson's disease: the relative importance of the symptoms. Movement Disorders. 2008;23(10):1428–1434. doi: 10.1002/mds.21667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Basnyat I, Chang L. Examining live-in foreign domestic helpers as a coping resource for family caregivers of people with dementia in Singapore. Health Communication. 2017;32(9):1171–1179. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2016.1220346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]