Abstract

Background

Breast cancer is the most devastating public health problem affecting women in developed and developing world. Therefore, this study was aimed to assess the likelihood of taking breast self-examination as a breast screening behavior among reproductive age women.

Methods

A community based cross-sectional study was conducted on 810 reproductive-age women. Intervieweradministered questionnaires were used to collect data. Study participants were selected using systematic sampling method. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 24.0.

Results

The likelihood of performing breast self-examination was 54.3%. However, the comprehensive knowledge of the participants was 11.5%. As independent predictors, perceived severity of breast cancer [AOR (95%CI) = 2.05 (1.03 to 1.07)] and self-efficacy [AOR (95%CI) = 2.97(0.36–0.99)] were positively associated with the likelihood of performing breast self-examination whereas districts [AOR (95%CI) = 0.58 (0.37 to 0.91)] and place of residence [AOR (95%CI) = 0.69 (0.51 to 0.93)] were negatively associated with the likelihood of performing breast selfexamination. The HBM Model explained 64.2% of the variance in this study.

Conclusion

Although the likelihood of performing breast selfexamination was relatively good, the comprehensive knowledge of the women was very low. Therefore, breast cancer screening education must address knowledge and socio-cultural factors that influence breast screening through awareness creation using appropriate behavioral change communication strategies.

Keywords: Behavior, Breast Cancer, Perception, Screening, Ethiopia

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most devastating public health problem affecting women all over the world. Worldwide, it is estimated that over 508,000 women died in 2011 due to breast cancer. Its incidence is increasing in the developing world due to increased life expectancy, urbanization and adoption of western lifestyles(1). According to the American Cancer Society (ACS), approximately 230,480 females in the US were diagnosed with breast cancer (2). One in eight women born today will be diagnosed with breast cancer at some time in life (3).

In Ethiopia, cancer accounts for about 6% of total national mortality (4). About two-thirds of the annual cancer deaths occur among women (5). Breast cancer takes the highest percentage containing 33.4% of the total cancers (4,6). Ethiopian women typically present for care at a late stage in the disease, where treatment is most ineffective (6–8).

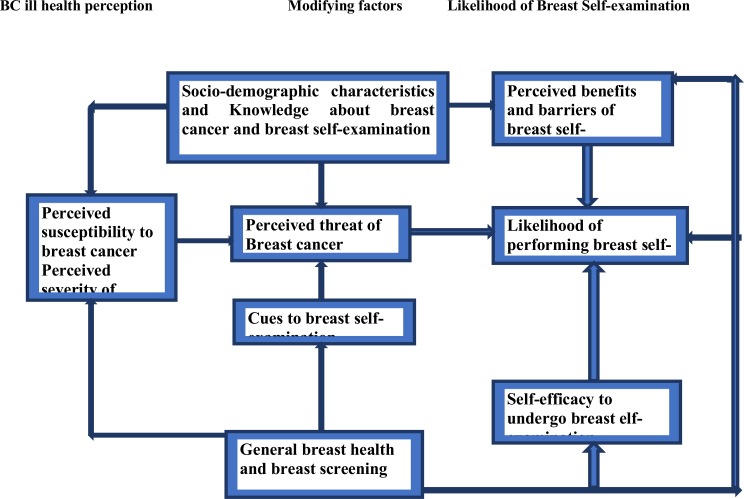

Screening is the most effective method to reduce morbidity and mortality from breast cancer. Breast self-examination, breast clinical exam and mammography are the methods of choice for early detection of breast cancer. However, the limited availability and high service cost associated with mammography makes breast self-examination (BSE) a convenient and cost-effective method in developing countries with less reliability (9). Unfortunately, studies have not been conducted or limited so far on the assessment of perception of BSE among reproductive age women in Hadiya Zone, Ethiopia. Therefore, this study was aimed to assess the likelihood of BSE as a breast screening behavior among reproductive age women based on the theoretical framework of the health belief model (HBM) (10, 11) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of the research

Materials and Methods

Study area and period: This study was conducted in Hadiya Zone, Ethiopia. The zone has twelve districts. It is located 230 km far from the capital city of Ethiopia. The estimated population of the zone is 1,650,104. The estimate of females in child bearing age (15–49) is 193,967 (12). The study period was as of May to June 2018.

Study design and populations: A community based cross-sectional study was conducted to assess the likelihood of performing BSE among reproductive age women as a baseline survey for cluster randomized controlled trial.

Sample size and sampling procedures: Since this study is a baseline for cluster randomized trial, the sample size was calculated using double population proportion formula by considering 77.6% of the participants who have knowledge about BSE as a screening method (P1 = 77.6%); P2 is the prevalence of screening rate in the intervention districts (87.6%) (Assumed to be increased by 10%); k is coefficient of variation of true proportions of the outcome variable between the districts within each group; Margin of error 5%, a 5% level of significance (two sided) i.e. 95% confidence interval of certainty. Since there was no study to estimate k, it was taken as 0.25. Then, the sample size was 368. Finally, the sample size was further increased by 10% to account for contingencies such as non-response or recording error, i.e. 368 X 10/100 + 368= 404.8 ≈ 405. Therefore, the final sample size was 810 due to design effect.

Measurement and variables: The intended outcome for this study was likelihood of performing breast self-examination (perceived benefits minus perceived barriers). The exposure variables were sociodemographic factors, knowledge of breast cancer and BSE, perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, selfefficacy, cues to actions and past behaviors screening. Socio-demographics characteristics such as age, marital status, religion, place of residence, educational status, occupational status and living conditions. There are 14 knowledge questions with response format of ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Respondents were asked not to guess, but to mark the “I don't know” option if they did not know the correct answer. Knowledgeable were those respondents who answered 50% and above of all the knowledge questions about breast cancer and BSE. Not knowledgeable were those respondents who could answer below 50% of all the knowledge questions about breast cancer and BSE. Perceived susceptibility was respondents' self-perception of vulnerability to breast cancer, measured by summed score of related belief items on 5-point Likert scale. Perceived severity of breast cancer was respondents' held belief concerning the effects of breast cancer seriousness, measured by summed score of related belief items on 5-point Likert scale. Perceived benefits of performing BSE was respondents' belief about the effectiveness of the method as a strategy for breast cancer prevention, measured by summed score of related belief items on 5-point Likert scale. Perceived barriers to perform BSE were respondents' belief about the ease of performing the given preventive action. Self-efficacy to use BSE was respondents' self-confidence to perform BSE by oneself in any condition and anywhere to prevent breast cancer measured by summed score of related belief items on 5-point Likert scale. Negatively worded items were reversed before calculating a summed score of each concept. Cues to actions were conditions that may facilitate them to perform BSE in the respondents' surroundings with response format of ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Past behaviors of BSE were those women who had performed at least once a month to prevent breast cancer infection measured with nominal measurements.

Factor analysis was done for validation of the instrument. This was confirmed by considering factor loading score of greater than or equal to 0.4 for construct validity. Cronbanch's Alpha was used to measure internal consistency of items accepted when greater than or equal to 0.7.

Data collection instrument and procedure: Data were collected using structured interviewer-administered questionnaires. The questionnaires were designed and adapted from various literatures in English to increase the comparability of the finding (7,8).

Data quality management, processing and analysis: Questionnaires were translated into local language and then back translated into English by another person to maintain its consistency. A two days' training was given for data collectors and supervisors. Supervisors and the principal investigator performed immediate supervision on a daily basis. The data were analyzed by SPSS V. 24.0. For uniform scoring of the items of the five point Likert scale response format, negatively constructed items were reversed. Descriptive analysis was used to describe the percentages and number of distributions of the respondents by socio-demographic characteristics, knowledge, past behaviors of breast cancer and the main constructs of HBM. Furthermore, Binary logistic regression was used to identify the independent predictors of BSE. The crude and adjusted odds ratios together with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals were computed and interpreted accordingly. A P-value <0.05 was used to declare results as statistically significant.

Ethics: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences with approval code IR.TUMS.SPH.REC.1396.4088 and project numbers 9513489001-292293. Ethical approval was also obtained from the Ethical Approval Committee of South Region Health Bureau of Ethiopia (Ref. No: S026-19/5524). Then, permission letter was secured from Hadiya Zone health Department. All the study participants were given detailed information about the study before data collection. This study has been registered in Pan African Clinical Trial Registry (www.pactr.org) database with unique identification number of PACTR201802002902886.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants: Eight hundred and ten reproductive age women were participated in the study giving a response rate of 100%. Table 1 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents. Accordingly, the mean age of the participants was 33.42 ± 7.81 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants in Hadiya Zone, Ethiopia

| Variables | Categories | Number | Percent (%) |

| Districts/Woredas | Lemo | 178 | 22.0 |

| Hossana | 123 | 15.2 | |

| Anlemo | 104 | 12.9 | |

| Duna | 172 | 21.2 | |

| Shone city | 53 | 6.5 | |

| Misha | 180 | 22.2 | |

| Age | 15–24 | 172 | 21.2 |

| 25–34 | 307 | 37.9 | |

| 35–44 | 265 | 32.7 | |

| 45–49 | 66 | 8.1 | |

| Current Residence | Rural | 595 | 73.5 |

| Urban | 215 | 26.5 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 78 | 9.6 |

| Married | 693 | 85.6 | |

| Divorced | 39 | 4.8 | |

| Religion | Protestant | 597 | 73.7 |

| Orthodox | 141 | 17.4 | |

| Muslim | 45 | 5.6 | |

| Catholic | 27 | 3.3 | |

| Educational status | Can't read and write | 453 | 55.9 |

| Can read and write | 197 | 24.3 | |

| Primary school | 41 | 5.1 | |

| High school | 59 | 7.3 | |

| College and above | 60 | 7.4 | |

| Occupational status | Government employee | 64 | 7.9 |

| House wife | 567 | 70.0 | |

| Merchant | 67 | 8.3 | |

| Private business | 65 | 8.0 | |

| Student | 47 | 5.8 | |

| Monthly income (measured in quartile) | Lower (<500) | 406 | 50.1 |

| Medium (501–1000) | 278 | 34.3 | |

| Higher (1001–1500) | 60 | 7.4 | |

| Highest (≥1501) | 66 | 8.2 |

Knowledge about breast cancer and breast selfexamination: The study revealed that the comprehensive knowledge of the respondents was 11.5% (93/810). However, 88.5%(717/810) of the participants were not knowledgeable.

Past behaviors related to breast cancer and breast self-examination: Table 2 presents the past behavior of the respondents about breast cancer and BSE. Accordingly, almost all the participants had heard of breast cancer. Then, 36.9%(299/810) of the participants had heard of BSE. However, a few had performed BSE 8.6%(70/810) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Respondents' past behaviors related breast cancer and its screening among reproductive aged women in Hadiya Zone, Ethiopia

| Variables | Yes | % | No | % | |

| Heard about breast cancer (N=810) | 774 | 95.6 | 36 | 4.4 | |

| Has heard of breast cancer prevention methods (N=810) | 299 | 36.9 | 511 | 63.1 | |

|

If yes, how did you know it? (N=299) |

Health worker | 277 | 92.3 | 23 | 7.7 |

| Mass media | 199 | 66.6 | 100 | 33.4 | |

| Relative | 183 | 61.2 | 116 | 38.8 | |

| Friends | 140 | 46.8 | 159 | 53.2 | |

| Ever caught by Breast cancer (N=810) | 810 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Ever screened before (N=299) | 70 | 23.4 | 229 | 76.6 | |

| If yes, screened (N=70) | A month ago | 7 | 10.0 | 63 | 90.0 |

| Before two months | 7 | 10.0 | 63 | 90.0 | |

| Before six months | 38 | 54.3 | 32 | 45.7 | |

| A year ago | 22 | 31.4 | 48 | 68.6 | |

| Two years ago | 3 | 4.3 | 67 | 95.7 | |

|

Which method did you use? (N=70) |

Mammography | 6 | 8.6 | 64 | 91.4 |

| Breast clinical exam | 17 | 24.3 | 53 | 75.7 | |

| BSE | 47 | 67.1 | 23 | 32.9 | |

|

If yes for screening, frequency breast screening (N=70) |

Sometimes | 40 | 57.1 | 30 | 42.9 |

| Usually | 3 | 4.3 | 67 | 95.7 | |

| Consistently | 7 | 10.0 | 63 | 90.0 | |

| Others* | 20 | 28.6 | 40 | 57.1 | |

Once, Haphazardly

Perception towards breast cancer and self-examination: The likelihood of performing breast self-examination was 54.3%. Table 3 summarizes perception scores of the participants about breast cancer and breast self-examination. Accordingly, perception of threat appraisals such as perceived susceptibility to and perceived severity of breast cancer had an average score of (mean ± standard deviation) (17.39 ± 4.64) and (38.84 ± 9.09) respectively whereas perceived benefits and barriers had average scores of (53.18 ± 9.74) and (69.90 ± 10.69) respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Perception scores of the participants about breast cancer and breast self-examination in Hadiya Zone, Ethiopia

| Variables | Score range | Mean±SD |

| Perceived Susceptibility | 5–25 | 17.39±4.64 |

| Perceived Severity | 11–55 | 38.84±9.09 |

| Perceived Benefits | 14–70 | 53.18±9.74 |

| Perceived Barriers | 19–95 | 66.90±10.69 |

| Perceived Self-Efficacy | 13–65 | 46.61±10.07 |

| Cues to Action | 0–7 | 3.74±1.97 |

| Health Motivation | 12–60 | 47.35±5.73 |

| Knowledge | 0–14 | 3.89±1.99 |

| Likelihood of taking action | 0–5 | 0.2±1.27 |

The independent predictors of likelihood of performing BSE: Binary logistic regression model was used to assess the effect of independent variables on likelihood of breast self-examination. Table 4 presents the independent predictors of BSE. Accordingly, perceived severity, self-efficacy, woreda/districts and current residence had significant crude and adjusted effects on likelihood of taking breast self-examination. The odds of participants who currently resided in urban areas was 31% less than from the odds of participants who resided in rural area in likelihood of performing breast self-examination [AOR (95% CI) = 0.69(0.51–0.93). Participants from Lemo and Duna were less protective than their counterparts in Misha districts.

Table 4.

Binary logistic regression to identify independent predictors of likelihood of taking breast selfexamination among reproductive age women in Hadiya zone, Ethiopia

| Variable | No (%) | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Woreda | Lemo | 178 (22.0) | 0.55 (0.36–0.84) | 0.58 (0.37–0.91) | 0.017 |

| Hossana Town | 123 (15.2) | 0.61 (0.39–0.98) | 0.72 (0.22–1.43) | 0.222 | |

| Anlemo | 104 (12.9) | 0.80 (0.32–0.49) | 0.83 (0.39–1.49) | 0.475 | |

| Duna | 172 (21.2) | 0.55 (0.36–0.85) | 0.60 (0.39–0.94) | 0.027 | |

| Shone town | 53 (6.5) | 0.59(0.09–0.32) | 0.65 (0.23–1.34) | 0.184 | |

| Misha | 180 (22.2) | 1 | 1 | ||

|

Place of Residence |

Rural | 595 (73.5) | 1 | 1 | |

| Urban | 215 (26.5) | 1.47(1.10–1.97) | 0.69(0.51–0.93) | 0.013 | |

| Severity | Mean +SD | 38.84±9.09 | 1.04(1.03–1.06) | 2.05(1.03–1.07) | 0.000 |

| Self-efficacy | Mean +SD | 46.61±10.07 | 2.98(0.37–0.99) | 2.97(0.36–0.99) | 0.001 |

NB. Variables indicated in the above table are significant in both crude and adjusted odds ratio.

Those participants who had high perceived severity were 2.05 times more likely to perform breast self-examination compared to low perceived severity [AOR (95% CI) = 2.05(1.03–1.07)]. Meaning, the more the severity is the more intention to be screened. Likewise, those participants who had higher odds of self-efficacy for likelihood of taking breast cancer screening behavior were 2.97 times more likely to perform breast self-examination compared to low self-efficacy [AOR (95% CI) = 2.97(0.3–0.99)]. In other words, self-efficacy enhances the likelihood of taking breast cancer screening behavior (Table 4).

Predicted final model (likelihood of taking BSE as a variable of interest) = 1.30 + 0.05 (perceived severity) -0.03 (self-efficacy) - 0.38 (residence) - 0.54 (woredas/districts) to show how the model explained about 64.21% of the likelihood of BSE among respondents residing in Hadiya Zone with goodness of fit of the model being X2/df= 54.28/5 =0.000.

Discussion

This study assessed the likelihood of performing breast self-examination in reproductive age women under the constructs of HBM. According to HBM, individual's perceived susceptibility to and severity of diseases lead to use of screening methods through recognizing the benefits from the barriers under the basic assumption that people are motivated for their health(13,14).

Accordingly, the current study found that the likelihood of performing breast self-examination was 54.3%. The pervious literatures also documented the likelihood of taking breast screening is determined by social, cultural and economic factors in rural poor (15–19).

In this study, knowledge about breast cancer and breast self-examination was found very low. Similarly, a number of cross-sectional studies conducted in northern Ethiopia and abroad support this idea (7,13,18). This is also supported by the concept of HBM that states that assessing motivational variables, awareness and screening behavior of individuals are possible where the services are available (14).

This study found that perceived severity of breast cancer was positively associated with likelihood of taking action. This is similar with many studies documented and the preceding qualitative study published elsewhere as part this study (7).

Many systematic reviews and meta-analyses documented that perceived benefits were the important predictor of cancer screening (17,20,21). However, the current study revealed that perceived benefit had no statistically significant effect in increasing the likelihood of performing BSE.

Previous studies reported that self-efficacy is the most predicting variable of taking breast selfexamination (7,18,22). In this study, self-efficacy was an important correlate of performing BSE. This is congruent with the concept of HBM which states that individuals might engage in screening behavior if they are confident to successfully undertake and cope with it (14,23).

Naturally, the uptake of breast screening varies from place to place (21,24). The current study also found that there was a statistically significant variation between the study districts. Similar findings were also documented in previous studies (16,24–26)

In conclusion, this study revealed that knowledge, perception and past behavior of the women to prevent breast cancer were the important determinants of breast self-examination. Women's breast self-examination was mostly determined by individual perception. As strength, the current study used tested model for message as a theoretical framework that outlines how to measure the components easily. However, as a limitation, HBM measures psychological responses; this might result in gap between the actual behavior and psychological responses.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all the participants for their patience and provision of important information. We are thankful to the International Campus of Tehran University Medical Sciences for funding this study. We also thank Hadiya Zone health Department for providing baseline information. Lastly, we would like to extend our gratitude to Wachemo University for financial support and duplicating questionnaires.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2013;63(1):11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeSantis C, Siegel R, Bandi P, Jemal A. Breast cancer statistics, 2011. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2011;61(6):408–418. doi: 10.3322/caac.20134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2016;66(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tigeneh W, Molla A, Abreha A, Assefa M. Pattern of cancer in Tikur Anbessa specialized hospital oncology center in Ethiopia from 1998 to 2010. Int J Cancer Res Mol Mech. 2015;1(1) doi: 10.16966/2381-3318.103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman M, Forman D, Bryant H, Butler J, Rachet B, Maringe C, et al. Cancer survival in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the UK, 1995–2007 (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): an analysis of population-based cancer registry data. The Lancet. 2011;377(9760):127–138. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62231-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abate Y, Yilma Z, Assefa M, Tigeneh W. Trends of breast cancer in Ethiopia. Int J Cancer Res Mol Mech. 2016;2(1):1. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birhane N, Mamo A, Girma E, Asfaw S. Predictors of breast self-examination among female teachers in Ethiopia using health belief model. Archives of Public Health. 2015;73(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s13690-015-0087-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alwan N, Al Attar W, Eliessa R, Madfaic Z, Tawfeeq F. Knowledge, attitude and practice regarding breast cancer and breast selfexamination among a sample of the educated population in Iraq. East Mediterr Health J. 2012;18(4):337–345. doi: 10.26719/2012.18.4.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agide FD, Sadeghi R, Garmaroudi G, Tigabu BM. A systematic review of health promotion interventions to increase breast cancer screening uptake: from the last 12 years. European journal of public health. 2018;28(6):1149–1155. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckx231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salem DS, Kamal RM, Mansour SM, Salah LA, Wessam R. Breast imaging in the young: the role of magnetic resonance imaging in breast cancer screening, diagnosis and followup. Journal of thoracic disease. 2013;5(Suppl 1):S9. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.05.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. International journal of cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–E86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hadiya Zone Report. Annual Report 2018, Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia. 2018. (2017 Population Projection) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hajian S, Vakilian K, Najabadi KM, Hosseini J, Mirzaei HR. Effects of education based on the health belief model on screening behavior in high risk women for breast cancer, Tehran, Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12(1):49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. John Wiley & Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arshad S, Williams KP, Mabiso A, Dey S, Soliman AS. Evaluating the knowledge of breast cancer screening and prevention among Arab-American women in Michigan. Journal of Cancer Education. 2011;26(1):135–138. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0130-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eskandari-Torbaghan A, Kalan-Farmanfarma K, Ansari-Moghaddam A, Zarei Z. Improving breast cancer preventive behavior among female medical staff: the use of educational intervention based on health belief model. The Malaysian journal of medical sciences: MJMS. 2014;21(5):44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu M, Moritz S, Lorenzetti D, Sykes L, Straus S, Quan H. A systematic review of interventions to increase breast and cervical cancer screening uptake among Asian women. BMC public health. 2012;12(1):413. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teferi S, Mezgebe T, Demissie M, Durgaprasada A. Knowledge about breast cancer risk-factors, breast screening method and practice of breast screening among female healthcare professionals working in governmental hospitals, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. IOSR Journal of pharmacy and biological sciences. 2012;2(1):5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arozullah AM, Calhoun EA, Wolf M, Finley DK, Fitzner KA, Heckinger EA, et al. The financial burden of cancer: estimates from a study of insured women with breast cancer. J Support Oncol. 2004;2(3):271–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agide FD, Garmaroudi G, Sadeghi R, Shakibazadeh E, Yaseri M, Koricha ZB, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness of health education interventions to increase cervical cancer screening uptake. European journal of public health. 2018;28(6):1156–1162. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cky197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agide FD, Sadeghi R, Garmaroudi G, Tigabu BM. A systematic review of health promotion interventions to increase breast cancer screening uptake: from the last 12 years. European journal of public health. 2018 doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckx231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collins C. Correlates of Breast Selfexamination: Application of the Transtheoretical Model of Change and the Health Belief Model. University of Cincinnati; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tuzcu A, Bahar Z, Gözüm S. Effects of interventions based on health behavior models on breast cancer screening behaviors of migrant women in Turkey. Cancer nursing. 2016;39(2):E40–E50. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO, author. Training for mid-level managers. Geneva, Swizerland: WHO; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson BO, Yip CH, Smith RA, Shyyan R, Sener SF, Eniu A, et al. Guideline implementation for breast healthcare in low-income and middle-income countries. Cancer. 2008;113(S8):2221–2243. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abate S, Yilma Z, Assefa M, Tigeneh W. Trends of Breast Cancer in Ethiopia. Int J Cancer Res Mol Mech. 2016;2(1) doi: 10.16966/2381-3318.121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]