Abstract

Community advisory boards (CABs) are a valuable strategy for engaging and partnering with communities in research. Eighty-nine percent of Clinical and Translational Science Awardees (CTSA) responding to a 2011 survey reported having a CAB. CTSAs’ experiences with CABs are valuable for informing future practice. This study was conducted to describe common CAB implementation practices among CTSAs; document perceived benefits, challenges, and contributions; and examine their progress toward desirable outcomes. A cross-CTSA collaborative team collected survey data from respondents representing academic and/or community members affiliated with CTSAs with CABs. Data representing 44 CTSAs with CABs were analyzed using descriptive statistics. A majority of respondents reported practices reflecting respect for CAB members’ expertise and input such as compensation (75%), advisory purview beyond their CTSA’s Community Engagement program (88%), and influence over CAB operations. Three-quarters provide members with orientation and training on roles and responsibilities and 89% reported evaluating their CAB. Almost all respondents indicated their CTSA incorporates the feedback of their CABs to some degree; over half do so a lot or completely. This study profiles practices that inform CTSAs implementing a CAB and provide an evaluative benchmark for those with existing CABs.

Keywords: Community advisory board, community engagement, community partnerships, best practices, implementation, survey

Introduction

Community advisory boards (CABs) can serve as a valuable strategy for engaging and partnering with communities in research [1–7]. CABs have the potential to provide researchers with the perspective of those most affected by health inequity, to help build authentic community-university relationships and trust, and to increase the relevance and effectiveness of research. Communities benefit when CABs can engage researchers in addressing members’ most pressing issues, help to build community members’ networks and capacity for positive change, and increase their access to resources and opportunities. Studies conducted in the context of community-based participatory research (CBPR) have documented some of the challenges, opportunities, and best practices for successful research partnerships with CABs [3, 4, 8, 9].

Researchers often establish CABs to advise on specific projects [1] or to provide overarching guidance for research entities at the institutional level. The Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) Program, administered by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) to support a national network of academic health science centers, has a program goal to “engage patients and communities in every phase of translational research” [10]. Eighty-nine percent of CTSAs responding to a cross-CTSA survey in 2011 reported having a CAB [2]. While this survey provided valuable data on the role of community representatives among CTSAs, the information collected about the practices of CTSAs implementing and sustaining CABs was limited in scope. CTSAs’ experiences with CABs are valuable for informing future practice. This paper shares new survey findings to describe common CAB implementation practices among CTSAs; document perceived benefits, challenges, and contributions; and examine their progress toward desirable outcomes.

Methods

Development of Cross-CTSA Collaboration

This paper describes a cross-CTSA collaboration of CTSA community engagement (CE) team members at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences’ Translational Research Institute (UAMS TRI), the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (VICTR), the Washington University in St. Louis’ Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences (WUSTL ), the South Carolina Clinical and Translational Research Institute (SCTR Institute) at the Medical University of South Carolina and the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research at the University of Michigan (MICHR). These collaborators, which included community partners from two of these institutions, held monthly conference calls from May through August 2017 focused on learning related to their CABs. UAMS TRI’s evaluator joined the research team after data collection to assist with data analysis. The research team shared information about their own CABs and conducted a literature review. After examining questions from previous CE-related surveys of CTSAs, they determined that minimal information about CTSA CABs had been collected through these more broadly focused surveys [2]. Therefore, the team decided to conduct a structured survey focused on identifying CAB implementation practices used by CTSAs.

Survey Instrument

The team developed the survey instrument (see Supplement) collaboratively through an iterative process, focusing survey content on documenting common CAB implementation practices among CTSAs as well as perceptions about the CAB. Specific instrument content related to implementation included questions on membership and selection processes, training, written documents, clearly defined responsibilities, extent to which the CAB influences its own operations, CAB purview, activities, logistics, and evaluation. Questions on the respondents’ perceptions about CAB member benefits, challenges, and contributions were also included. The content of the instrument was determined based on team members’ knowledge and experiences with CABs and through reviewing the literature to identify gaps and questions used in previous studies of CTSAs [2]. This review identified only two papers with data related specifically to CTSA CABs published prior to the time of survey development, even though others were published after we fielded our survey [5, 6, 11]. Halladay’s paper about research-related CABs that are working with their CTSA informed specific questions we included about CAB practices [7], but we found only one paper reporting data collected across the CTSAs published at the time of survey development that included questions specifically about CTSA CABs [2] and this paper did not describe implementation practices.

The survey was programmed into REDCap, a secure online survey web application [12]. Team members pre-tested the instrument by completing it themselves and making necessary revisions before distribution. A letter of determination about the survey project was submitted to UAMS’ Institutional Review Board (IRB), which classified this study as exempt from IRB review.

Data Collection

Survey respondents were recruited using convenience and purposive sampling as follows. The survey was launched at the national conference on “Advancing the Science of Community Engaged Research” in September 2017, which was attended by many investigators, staff, and community partners involved in CTSA CE research. Conference attendees received a paper survey and the link to the online survey but only three were completed on paper. Team members also promoted the survey on the monthly CE Brokers/Managers call and on the monthly call of Partners for the Advancement of Community Engaged Research (PACER) group in which many CE researchers involved in CTSAs participate. Lastly, the team developed a database of CTSA CE leadership and sent personal emails to non-respondents. These recruitment efforts resulted in 81% (52/64) of identified CTSAs having either academic and/or CAB members completing the survey, with representatives from 44 CTSAs with a CAB completing the full survey. Paper surveys were entered into REDCap and the complete dataset was then exported, cleaned and analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS).

Data Preparation

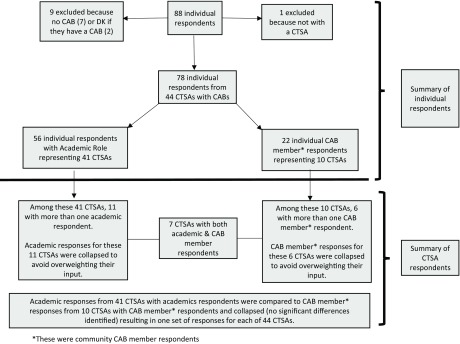

Descriptive statistics were generated and reviewed to inform creation of new variables and finalize the analytic dataset. New variables included role with the CAB, level of influence over CAB operations, CAB purview, compensation and number of ways of being involved in research. Seventy-eight individuals affiliated with 44 CTSAs with CABs responded to the survey (Fig. 1). In the interest of comparing academic responses with community CAB member (hereafter referred to as CAB member) responses, and to avoid over weighting CTSAs with more respondents, a new dichotomous variable was created to identify the respondents’ role with their CAB (i.e., Academic/CTSA or CAB member). Table 1 provides the unduplicated distribution of academic and CAB member respondents by CTSA. Eleven CTSAs had multiple academic respondents and six had multiple CAB member respondents. Responses from CTSAs with more than one academic or CAB respondent were collapsed by averaging or combining responses from academics and from CAB members separately, resulting in 41 academic and 10 CAB responses, respectively. Because chi-square statistics comparing responses between academic and CAB members did not detect significant differences, responses for the seven CTSAs with both CAB and academic respondents were collapsed or combined, resulting in 44 CTSA responses included in the final analysis.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of respondents in final analysis dataset. Abbreviations: CAB, community advisory board; CTSA, Clinical and Translational Science Awardees; DK, don't know.

Table 1.

Distribution of Respondents by Clinical and Translational Science Awardees (CTSA)

| (Duplicated academic & community advisory board (CAB) member* & unduplicated total) | Duplicated respondents | Unduplicated CTSAs represented |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Academic | CAB* | ||

| Boston University Clinical & Translational Science Institute (CTSI) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Case Western Reserve University Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Columbia University, Irving Institute for Clinical and Translational Research | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Dartmouth College, Dartmouth Geisel School of Medicine | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Georgetown-Howard Universities Center for Clinical and Translational Science | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| George Washington University CTSI at Children’s | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Goldfarb School of Nursing, CAB, Executive Board Center for Community Health Partnership and Research | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Harvard Catalyst | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Indiana CTSI | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Mayo Clinic Community Engagement in Research | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Northwestern University—Alliance for Research in Chicagoland Communities Steering Committee | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ohio State | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Oregon Health & Science University | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Scripps Translational Science Institute | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| South Carolina Clinical and Translational Research Institute (Medical University of South Carolina) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Tufts CTSI | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Unidentified CTSA | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| University of Alabama at Birmingham | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences/Translational Research Institute | 4 | 7 | 1 |

| University at Buffalo | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| University of California—Davis | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| University of California—San Diego; Clinical and Translational Research Institute | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| University of Chicago | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| University of Cincinnati | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| University of Colorado—Colorado CTSI | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| University of Florida CTSI | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| University of Illinois at Chicago | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| University of Iowa Institute for Clinical and Translational Studies | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| University of Kansas Medical Center | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| University of Miami | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| University of Minnesota CTSI | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| University of Pittsburgh CTSI | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| UT Health San Antonio | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| University of Texas Medical Branch | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| UT Southwestern | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| University of Utah Center for Clinical and Translational Science | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| University of Wisconsin Institute for Clinical and Translational Research | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Virginia Commonwealth University | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Wake Forest | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Washington University | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Weill Cornell Clinical and Translational Science Center | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Yale | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 56 | 22 | 44 |

| CTSAs with more than one academic and/or community respondent | 11 | 6 | -- |

| CTSAs with both academic and community respondents | 7 | ||

Community CAB member respondents.

To reflect the CAB’s influence over its operations, a level of influence variable was created by identifying practices pulled from three multiple select questions (Q19, Q23, and Q27) about practices that may increase a CAB’s level of influence over its operations. The values for the level of influence variable range from 0 to 3, assigning one point for each of the three questions that met at least one of the following identified practices. Specifically, one point was recorded for the question (Q19): “Who decides who will serve on the CTSA CAB?” if respondents selected “CAB members or other community members.” One point was recorded for the question (Q23): “Which of the following documents do CAB members have input on?” if they selected “bylaws,” “job description for members,” “meeting agendas,” “memorandum of agreement,” “mission statement,” “operating principles,” or “other documents.” One point was recorded for the question (Q27): “Which of the following leadership roles does your CAB have?” if they selected “community chairperson” or “subcommittee or working group chairperson.”

Two dichotomous variables were created to reflect implementation practices. Specifically, for the multiple select question (Q7): “Who does the CAB advise?” a CAB purview variable was created by assigning “Only CE” a value of 0 for those that only selected “Community Engagement Program” and assigning “More than CE” a value of 1 for those that selected “Academic Institution,” “CTSA leadership” and/or “Other” (where “Other” was described as more than their CE program). Additionally, for the multiple select question (Q28): “How are CAB members compensated for their CTSA activities?” a new compensation variable was created by assigning 0 to those selecting “Not compensated” or “Don’t know” and 1 to those selecting “Per meeting,” “Annually,” “Hourly rate,” “Reimbursement for meals,” “Reimbursement for travel expenses,” “Member’s employer receives compensation,” or “Other” (where “Other” was described as some form of compensation).

For the multiple select question (Q9): “In what ways have CAB members been involved in research as a result of being on the CAB?,” a new variable was created to weight the number of ways CAB members were reported as being involved in research by assigning a value of 0 to those checking 0–3 options, 1 for those selecting 4–7 options, and 2 for those selecting 8 or more options.

Results

Membership and Selection Process

Respondents reported a wide distribution of organizations and individuals as CAB members. All but one CTSA reported CAB members representing lay interests (advocacy organizations, faith-based entities, neighborhood associations, non-profit community-based organizations, patients, tribal organizations, unaffiliated community members or members from special populations, and youth); 73% reported clinician members, and 73% reported members representing healthcare businesses, community health centers, or health insurance interests. CTSAs also reported governmental (66%), non-CTSA academic institutional (61%), and non-healthcare business (32%) representatives on their CABs. Specific examples provided as “other” responses which are incorporated above included community volunteers/members not affiliated with any organization, health department, education leader, recreation, community hospital board member, local funder, department of aging, LGBTQ, veterans, refugee service providers, local science museum, mental health expert on youth trauma, patient, residents in a poor section of city, statewide organizations like the MA League of Community Health Centers and the MA Association of County and Community Health Officers, and veterans.

New CAB members were identified primarily through referrals from current CAB members (86%), word of mouth/networking (75%), and/or through an application process (20%). CAB members were also identified through the CTSA/CE Program and through previous CTSA/community partnerships. Selection decisions about CAB members were made by CAB members or other community members (59%), CE Core leadership/staff (48%), CTSA leadership, and/or academic institution faculty (30%) and/or staff (25%).

Training and Documentation

Training for CAB members by CTSA academic institutions included an orientation to the CTSA (73%), CAB roles and responsibilities (75%), CE research and CBPR (64%), research ethics (36%), “Research 101” (34%), and information about being a grant reviewer (27%). Nine percent of respondents did not know if their CTSA provided training for CAB members.

Ninety-six percent used meeting agendas to document CAB activities. Other documents used were mission statements (52%), operating principles (43%), and job descriptions for members (39%). Only 30% reported using a memorandum of agreement (MOA) or bylaws. CAB members had input on CAB meeting agendas (77%), their mission statements (48%), and CAB operating principles (46%), with fewer reporting having influence over bylaws (36%), member job descriptions (34%), or MOAs (18%). About 9% did not know about documentation utilized within the CAB.

Roles and Responsibilities

CAB member responsibilities included participating in scheduled meetings (91%); serving as a liaison between the community and the academic institution (82%); advising the CE program (84%), the entire CTSA (36%), CTSA related programs (59%) (e.g., training, pilot grant programs, etc.); providing input on the strategic direction of the CTSA/CE program (71%); and/or responding to investigator’s requests for feedback (75%). Community-facing responsibilities included disseminating research opportunities and findings in the community (66%), helping with research recruitment (57%), and/or raising research awareness in the community (75%). A community member serves as the chairperson in 55% of the CABs.

Extent to Which CAB Influences Its Operations

Of the three questions (Q19, Q23, and Q27) each dichotomously scored to assess the CABs’ level of influence over the CAB’s own operations, over a third of CABs reflected the highest level of influence over the CAB’s operations (a score of 3) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Community advisory board (CAB) influence over its own operations*

| Level of influence | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11 | 25.0 |

| 2 | 17 | 38.6 |

| 3 | 16 | 36.4 |

| Total | 44 | 100.0 |

Based on responses to questions Q19: “Who decides who will serve on the CTSA CAB?,” Q23: “Which of the following documents do CAB members have input on?” and Q27: “Which of the following leadership roles does your CAB have?”

CAB Purview: Who Does the CAB Advise?

Of interest is how many CABs have influence on CTSA leadership beyond their CE programs. While 84% reported that their CAB advises their CE program, 71% percent of CABs advised CTSA leadership and 36% advised their academic institution overall. Specific responses written in by respondents included: advises [their CTSA] leadership about funding decisions, provides feedback to Pilot Award applicants about quality of CE, sets the strategy for the Communitywide Health Improvement program, advise investigators seeking [their CTSA] support for community based projects, and advise researchers, study investigators and project managers, and that they are working on better integrating CAB input into our larger CTSA system. Only 12% reported their CAB was only advising CE.

CAB Meetings, Terms, Compensation, and Communication

Forty-one percent of CABs had quarterly meetings. Others met monthly (27%), bimonthly (16%), annually (5%), semi-annually (2%), tri-annually (2%), or at varied intervals (7%). Three-quarters of the CABs met for 1–2 hours per meeting. Meetings tended to be longer for CABs that met less frequently. For example, of those that met quarterly, 22% met for 3–4 hours vs. of those that met monthly, 8% met for 3–4 hours. Forty-one percent of CABs reported members’ terms of service being 1–3 years and 21% reported terms of more than 3 years. Twenty-three percent did not know or did not respond regarding length of CAB members’ terms and 14% have no term limits.

Twenty-three percent of the CTSAs do not compensate their CABs. Among those who do, 53% compensate per meeting ($75–$300 per meeting), while 27% compensated members annually and 9% paid an hourly rate ($20–$50 per hour). Twelve percent reported their CAB members’ employer receives compensation and 32% only reimbursed for travel expenses. The monetary value of CAB member compensation varied from a minimum of $20 gift cards for community members to one CTSA that reported paying $2,500–$3,000 annually to CAB leadership (e.g., CAB chair) with members receiving less.

All reported CAB and CTSA communication between meetings by email with 64% communicating by phone. Twenty-seven percent used the method preferred by individual CAB members and 11% communicated in-person as needed through arranged meetings, over coffee, or for lunch. Some reported using a listserv (18%), online password protected space (7%), social media (5%), and private messaging software or texting (7%). Only one respondent reported using physical mail.

CAB Evaluation Data and Methods

Respondents reported on the type of data collected to evaluate their CAB. Meeting attendance records (75%), implementation of CAB recommendations (57%) and the number of CAB meetings (50%) were the most common data sources for evaluating CAB activities. About a third reported using researchers’ feedback on CAB consultations received, collecting participation data on subcommittees or working groups, or CAB member satisfaction surveys. Eleven percent have not evaluated their CAB and 14% did not know if it was evaluated. Over half used meeting minutes and/or sign-in sheets for evaluation, while some administered surveys (43%), conducted interviews (32%), and/or focus groups (14%) with CAB members.

CAB Contributions

The most common responses for “the three most important contributions of the CAB” included building partnerships between academic institutions and the community (73%), building trust between academic institutions and the community (68%), advising the CTSA/CE program on community health priorities and concerns (66%), representing community interests (55%), and increasing CE in research (52%). Some indicated helping communities better understand research (36%) and/or increasing research participation of underrepresented populations (34%) were among the top three contributions of their CAB.

Benefits to Community CAB Members

The most frequently reported benefits to community members of participating in the CAB was opportunities to network (93%), followed by organizational recognition (61%), access to academic institution resources and opportunities (61%), training opportunities (59%), leadership development (57%), and better understanding of community needs (55%). Other benefits reported included compensation for participation, involvement in research projects that benefit the health of CAB members’ communities, influence over decisions about funding priorities for healthcare research, and keeping up to date with research. Respondents also reported on a number of resources and opportunities CAB members could access through academic partner institutions including funding opportunities; library and other information resources; trainings, seminars, workshops, and conferences; employment and research-related opportunities; partnerships; and technical assistance.

Challenges

The most common challenges for CABs have been competing priorities that limit CAB member involvement between meetings (50%), meeting attendance (48%), CAB members’ uncertainty about how to contribute (45%), communication between meetings (43%), member turnover (23%), and CAB members not understanding their role (20%). Eleven percent indicated the lack of compensation for CAB member involvement outside of regular meetings and timeliness of compensation payments as challenges. Other challenges included members not feeling valued by CTSA or university leadership or lack of faculty understanding of how best to use a CAB.

CAB Member Research Involvement

Over half of respondents reported CAB members served as research consultants, grant reviewers, CE studio or review board experts, members of research project advisory councils, or conference presenters. Other research involvement included being a community co-investigator (48%), recruiting participants (39%), facilitating (34%), co-authoring papers (36%), and/or service on a CTSA consortium committee/working group (21%), on a CTSA leadership council (21%), as a research participant (21%), or as an IRB committee member (11%).

Respondents could select any of 13 suggested ways CAB members were involved in research or specify an “other” way. The research team assumed CAB members involved in research in many different ways would have the potential for more influence over research. The number of ways CAB members were involved varied across CTSAs as follows: 36% reported less than four ways, 43% reported 4–7, and 21% reported eight or more forms of involvement.

Incorporation of CAB Feedback and Addressing CAB Goals

Over half of respondents indicated their CABs were addressing the CAB’s purpose and goals a lot or completely. Respondents reported their CTSA incorporated CAB feedback either somewhat (39%), a lot (52%), or completely (5%).

Suggestions for How CTSAs Can Better Utilize Their CABs

Table 3 summarizes responses to Q32 which asked how CTSA CABs can be better utilized. Themes included integration of CAB members into other CTSA activities/programs, increased engagement/exchange of practices across the CTSA consortium, increased involvement of community members in research activities, advising institutional leadership about community needs/concerns, increased diversity of community representation, evaluation, and more focus on community priorities. Several activities suggested here were also reported in the survey as already being practiced by some CTSAs. For example, 66% of CTSAs reported that their CAB is advising CTSA leadership about community priorities and concerns. Results described above are summarized in Table 4 to show some of the most commonly reported CAB practices across the CTSAs.

Table 3.

Suggestions of ways Clinical and Translational Science Awardees (CTSAs) can better utilize their community advisory boards (CABs)

| Individual CTSAs | • Include CAB members on all core components |

| • Improve engagement with external advisory board | |

| • Provide input on pilot studies and trainees | |

| • Provide stronger infrastructure and support for broader CTSA input | |

| CTSA consortium | • Send two CAB representatives per site to national meeting |

| • Share rather than duplicate functions across CTSA network | |

| • Share CAB policies and documents across the consortium | |

| • Share success stories, case studies across the consortium | |

| • Include CAB member on Domain Task Force | |

| • Develop standard training for CTSA CABs | |

| Research activities | • Help tailor projects for communities where CAB members have expertise |

| • Assist with engaging communities of color in proposed research | |

| • Engage CAB in dissemination activities | |

| Institutional leadership | • Inform leadership about community needs and resources |

| CAB diversity | • Increase patient representation |

| • Use diverse modalities to recruit more diverse membership | |

| • Increase geographic diversity | |

| • Include business interests | |

| • Increase participation of majority population | |

| Evaluation | • Annual evaluation of goals; compare with previous year |

| • Get CAB input on how to increase their participation | |

| • Evaluate community engagement strategies | |

| Community priorities | • Share current issues in communities represented by CAB members |

| • Increase reciprocity: prioritize health and research interests from communities | |

| • Tap into CAB knowledge of local communities |

Table 4.

Most commonly reported community advisory board (CAB) implementation practices and benefits

| CAB operations | 1. Meetings are monthly, bimonthly or quarterly |

| 2. Meeting times are mostly 1–2 hours | |

| 3. CAB members are compensated for their participation on a per meeting basis and/or through travel reimbursement. Compensation varied from $20–$50/hour, $75–$300/mtg | |

| CAB member responsibilities | 1. Advise the community engagement (CE) program and/or CTSAs (less common). |

| 2. Serve as a conduit between the community and the academic institution | |

| 3. Respond to researchers’ requests for feedback | |

| 4. Raise awareness about research within their community. | |

| Research involvement | CAB members most commonly served as |

| 1. Research consultants | |

| 2. Grant reviewers | |

| 3. CE studio or review board experts | |

| 4. Conference presenters | |

| Information sharing | Information and research findings are shared through |

| 1. Community meetings | |

| 2. Community coalitions | |

| 3. Places of employment | |

| Most important contributions | 1. Building partnerships and trust between academic institutions and the community |

| 2. Advising the CTSA/CE about community health priorities and concerns and representing community interests | |

| Benefits of participating in CABs | 1. Networking |

| 2. Access to institutional resources (e.g., library, training, grants) | |

| 3. Opportunity for recognition |

Discussion

Several CTSAs have reported on the work of their individual CABs [5–7]. While previous work has documented the use of CABs across CTSAs [2, 11], to our knowledge, our study is the first to extensively document CAB implementation practices across CTSAs. Our findings, based on a survey with 81% of CTSAs represented and 86% of respondents reporting having a CAB, are important in documenting which practices are more common across CTSAs as well as where greater practice variation exists.

Newman et al. have identified CAB member role and purpose definition, compensation, training, evaluation, and written agreements as among some of the best processes for CABs in CBPR [4]. Similarly, Ortega et al documented that CAB members prioritized understanding their roles and responsibilities and a standardized orientation for new members as important needs [13]. Our findings indicate many CTSAs have implemented practices relevant to these issues. Three-quarters provide member training on roles and responsibilities and the same proportion reported compensating their CABs. Eighty-nine percent reported evaluating their CAB. However, only 30% reported having a written agreement outlining board expectations.

One purpose in asking about CAB roles and responsibilities was to explore whether CABs play a leadership role. The role of some CABs may be more to provide feedback on ideas brought to them by the CE team or CTSA leadership, while other CABs may do their own strategic planning and bring forth their own ideas to the CTSA leadership resulting in a more bi-directional relationship. We found the percentage reporting that their CAB members have an advising role (84%) was higher than those reporting that CAB members provided strategic input (71%), but it is impossible to say whether these reporting differences reflect the distinctions we intended to capture.

Our survey as well as the 2011 survey of CTSA CABs [2] identified multiple research-related roles that community representatives played as a result of being part of the CAB (e.g., community co-investigator, grant reviewer, facilitator, co-author, etc.). Others have taken on the role of informing their communities about the value of research and the importance of community involvement, as both research participants and research advisors. Many were involved in multiple research-related activities, and some CAB members have gone on to serve in leadership roles on national committees and large multi-center trials. CAB membership, then, appears to be an effective channel for increasing community involvement more broadly in translational research. The question of how being on a CAB might prepare community members for further roles in research is an area where additional study could be fruitful.

Inquiry about the relative importance of CABs as an engagement strategy was beyond the scope of our study. However, it would be helpful to know how much CTSAs rely on and invest in their CABs as a mechanism for engagement and direction on advising CTSAs compared to other strategies, as well as how they view the effectiveness and value of the various CE strategies they use. More research is needed on longer term outcomes such as how the structure of different CABs relates to metrics like funding, recruitment, publication, and implementation, etc.

Another important question remaining is whether differences exist between CTSA CABs and academic perspectives on the issues studied here. We did not find patterns in differences assessed qualitatively and found no significant differences by chi-square analysis in our study because of the small number (7) of CTSAs that had both CAB and academic respondents. However, we cannot say that significant differences would not exist between academic and CAB members if we could assess this across a broader range of CTSAs.

Limitations

There are several limitations to our study. We did not obtain an outside review of our survey instrument prior to launching the survey so it is possible that questions and/or response options were inadvertently excluded that might have been helpful to include. However, we hope this problem is minimized through inclusion of an “other” write-in option for most questions.

We did not limit the number of respondents who could complete the survey from each CTSA. We also allowed both community CAB members and those with an academic role in the CTSA to respond, as long as they were involved in the CAB in terms of “membership, facilitation, or planning.” Individual responses from the sixteen of the 44 responding CTSAs having more than one respondent (Table 1) were combined or collapsed to avoid overweighting input from individuals CTSAs. If any of these 16 CTSAs had multiple entities considered as CTSA-connected, then respondents may have completed the survey in reference to different CABs. Our approach of collapsing responses could potentially be problematic in these cases, though they are likely relatively small in number.

The only definition we provided for CAB was that it be a “currently active CAB or another committee sponsored by your CTSA that involved outside stakeholders and community partners other than the External Advisory Board.” It is possible that respondents may have replied based on their work with a project-specific CAB rather than a CAB designed to advise the CTSA but this is unlikely because recruitment targeted CTSA CE leaders and because many of the questions are framed in the context of advising the CTSA.

Conclusion

A majority of CTSAs with CABs reported practices reflecting respect for CAB members’ expertise and their input such as compensation, advisory purview beyond CE, and influence over CAB operations. While the percent of CTSAs providing members with compensation in our study (75%) is similar to the percent reported by Wilkins et al. in their 2011 survey (79%), the percent of CABs now reported as advising more than the CE program (88%) is an encouraging improvement over the 32% documented in the 2011 study.

Ninety-six percent of our respondents indicated their CTSA incorporates the feedback of their CABs to some degree, with over half stating they do so a lot or completely. This is an encouraging indicator of the impact of CTSA CABs. The investment involved in establishing and sustaining an effective CAB can be considerable. This study provides a profile of CAB implementation practices among CTSAs using this engagement strategy. We hope these data are helpful to CTSAs who may be implementing a CAB for the first time and that our results can provide an evaluative benchmark for existing CTSAs and CAB members to consider when reviewing their own practices and impact of their CABs.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the individuals from the CTSAs and from the community who volunteered to participate in the survey. We also appreciate feedback from the journal’s anonymous reviewers, which helped us to improve the quality of this paper.

Footnotes

Financial Support

Research reported on here was supported by: the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Translational Research Institute grant U54TR001629 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (MKS, BB, AHD, LPJ, RH, and NS) and by the Arkansas Center for Health Disparities Award ID 5U54MD002329 from the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities (MKS and AHD); the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research UL1 TR002243 from the NCATS, and the Meharry-Vanderbilt Alliance (YJ); the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1TR002345 from the NCATS (HB); the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) South Carolina Clinical and Translational Research Institute UL1 TR001450 from NIH/NCATS (DB); and the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research UL1TR002240 from NIH/NCATS (KC and PP). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts to disclose and all funding sources are described in Financial Support.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2019.389.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- 1. Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force C. Principles of Community Engagement, Second Edition Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf. Accessed January 2, 2019.

- 2. Wilkins CH, et al. Community representatives’ involvement in clinical and translational science awardee activities. Clinical and Translational Science 2013; 6(4): 292–296. doi: 10.1111/cts.12072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Delaney EM, et al. Community advisory boards in HIV research: current scientific status and future directions. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 2012; 59(4): e78–e81. http://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&from=export&id=L364620781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Newman SD, et al. Community advisory boards in community-based participatory research: a synthesis of best processes. Preventing Chronic Disease 2011; 8(3): A70 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21477510. Accessed January 25, 2018. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Matthews AK, et al. A Community Engagement Advisory Board as a strategy to improve research engagement and build institutional capacity for community-engaged research. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 2018; 2(2): 66–72. doi: 10.1017/cts.2018.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Matthews AK, et al. Development, implementation, and evaluation of a Community Engagement Advisory Board: strategies for maximizing success. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 2018; 2(1): 8–13. doi: 10.1017/cts.2018.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Halladay JR, et al. Community Advisory Boards guiding engaged research efforts within a clinical translational sciences award: key contextual factors explored. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research Education and Action 2017; 11(4): 367–377. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2017.0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Safo S, et al. “A place at the table:” a qualitative analysis of community board members’ experiences with academic HIV/AIDS research. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2016; 16(1): 80. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0181-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Morin SF, et al. Community consultation in HIV prevention research: a study of community advisory boards at 6 research sites. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 2003; 33(4): 513–520. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12869841. Accessed January 3, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. About the CTSA Program https://ncats.nih.gov/ctsa/about. Accessed January 3, 2019.

- 11. Evans E, et al. Defining and measuring community engagement and community-engaged research: CTSA institutional practices HHS public access. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research Education and Action 2018; 12(2): 145–156. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2018.0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. REDCap. https://www.project-redcap.org/. Accessed July 27, 2018.

- 13. Ortega S, et al. Perspectives of Community Advisory Board Members in a Community-Academic Partnership. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 2018; 29(4): 1529–1543. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2018.0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2019.389.

click here to view supplementary material