Abstract

Clinical xenotransplantations have been hampered by human preformed antibody-mediated damage of the xenografts. To overcome biological incompatibility between pigs and humans, one strategy is to remove the major antigens [Gal, Neu5Gc, and Sd(a)] present on pig cells and tissues. Triple gene (GGTA1, CMAH, and β4GalNT2) knockout (TKO) pigs were produced in our laboratory by CRISPR-Cas9 targeting. To investigate the antigenicity reduction in the TKO pigs, the expression levels of these three xenoantigens in the cornea, heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, and pancreas tissues were examined. The level of human IgG/IgM binding to those tissues was also investigated, with wildtype pig tissues as control. The results showed that αGal, Neu5Gc, and Sd(a) were markedly positive in all the examined tissues in wildtype pigs but barely detected in TKO pigs. Compared to wildtype pigs, the liver, spleen, and pancreas of TKO pigs showed comparable levels of human IgG and IgM binding, whereas corneas, heart, lung, and kidney of TKO pigs exhibited significantly reduced human IgG and IgM binding. These results indicate that the antigenicity of TKO pig is significantly reduced and the remaining xenoantigens on porcine tissues can be eliminated via a gene targeting approach.

Keywords: pig, xenotransplantation, GGTA1, CMAH, β4GalNT2, antigenicity

Introduction

Clinical transplantation has been improved enormously in recent decades; however, there is a major disparity between the number of patients awaiting transplantations and the available donor organs and tissues such as the hearts[1], livers[2– 3], kidneys[4– 6], lungs[7– 8], islets[9– 10], and corneas[11– 12]. Xenotransplantation using pig tissues/organs has been considered as a potential solution to alleviate the shortage of donor tissues/organs[13– 14]. A key barrier to xenotransplantation is the destruction of porcine xenografts that occurs when preformed human antibodies activate the complement system after binding to the xenogeneic antigens on the surface of pig cells[15– 16]. Galactose-α1,3-galactose (αGal), the most abundant immunogenic glycan in pigs to which the human immune system is highly responsive, has long been known as the causative xenoantigen associated with hyperacute rejection of a xenograft. Disrupting porcine αGal antigen expression via inactivating the α1,3-galactosyltransferase (GGTA1) gene conveys protection against hyperacute rejection[17– 18]. However, antibody-mediated rejection is not eliminated even in GGTA1-deficient porcine tissues harboring complement inhibitory receptor transgenes, revealing the significance of non-Gal antigens expressed on pig tissues[19– 21]. Continued pursuit of xenoantigens in pigs has led to the identification of other glycans associated with xenograft injury induced by highly specific circulating human antibodies, including N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc) encoded by the cytidine monophospho-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase (CMAH) gene and DBA-reactive glycans (also named Sd(a) antigen) produced by β-1,4-N-acetylgalactosaminyl transferase 2 (β4GalNT2)[22– 23]. To transplant porcine grafts into patients, eliminating xenoantigens responsible for antibody-mediated rejection must be achieved. Genetically modified pigs lacking αGal and Neu5Gc carbohydrate modifications have subsequently been produced, including GTKO/CMAH knockout (KO) pigs[24– 25], GTKO/CD46/CMAH KO pigs[24], and GGTA1/CMAH/ASGR1 KO pigs[26], in which human antibody binding is dramatically reduced.

More recently, GGTA1/CMAH/β4GalNT2 triple gene knockout (TKO) pigs have been established by Estrada et al[27] and Zhang et al[28] for further lowering their tissue xenoantigenicity. Compared to wild-type pigs, human IgG/IgM binding to peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and red blood cells from TKO pigs is significantly reduced[27,29]. However, the expressions of αGal, Sd(a) and Neu5Gc in other tissues/organs of TKO pigs and related human antibody binding have not been determined. Thus, the aim of this study was to broaden the antigenicity investigation into corneal tissues and solid organs including the liver, lung, spleen, heart, and kidney from TKO pigs.

Materials and methods

Animals

The GGTA1/β4GalNT2/CMAH triple gene knockout pigs were generated by Zhang et al[28] from our group. The sgRNAs for porcine GGTA1, β4GalNT2, and CMAH gene targeting are 5'-GAAAATAATGAATGTCAA-3', 5'-GGTAGTACTCACGAACACTC-3', and 5'-GAGTAAGGTACGTGATCTGT-3', respectively. The genotypes of TKO pigs in the present study are GGTA1: + 1 bp; CMAH: + 1 bp; β4GalNT2: −10 bp. Tissue samples of the heart, lung, kidney, liver, spleen, pancreas and cornea were collected from TKO pigs and age-matched wild type pigs. Corneas from GTKO/ CD46 porcine were kindly gifted by Dr. Dengke Pan. All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the guidelines approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China.

Histologic analyses

Tissue samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Five micrometer paraffin sections of heart, lung, kidney, liver, spleen, pancreas and cornea tissues were prepared after being dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated in gradient alcohol. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and mounted with neutral balsam, and the images were captured using a microscope (Nikon, Elgin, IL).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

To investigate the distribution of αGal and Sd(a) antigens in porcine tissues, sections were prepared after being dewaxed in xylene, rehydrated in gradient alcohol, and antigens unmasked in citrate solution. After wash with PBS, the slides were incubated with diluted GS-IB4 (concentration 1 : 1 000; Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) or DBA (concentration 1 : 400; Vector Laboratories) in each for 60 minutes at room temperature in the dark. For Neu5Gc detection in tissues, a chicken anti-Neu5Gc antibody kit (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) and goat anti-chicken IgY Alexa Fluor488 (Invitrogen) as a secondary antibody were successively used to stain the antigen unmasked slides. After PBS wash, 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Invitrogen) was used for nuclear staining in all cases. The distribution of glycans was detected under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon).

To determine human antibody binding, antigen unmasked slides were incubated with diluted, heatinactivated human serum for 30 minutes (diluted to 20% for IgM and to 5% for IgG binding). PBS was used as a negative control. After wash in PBS, the slides were blocked with 10% goat serum for 30 minutes at room temperature. Goat anti-human IgG Alexa Fluor 488 or donkey anti-human IgM Alexa Fluor 488 (concentration 1 : 1 000; Invitrogen) was applied for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark for detection of IgM or IgG binding. DAPI was applied for nuclear staining, and the slides were examined by a fluorescence microscope (Nikon).

Results

Expression of αGal, Sd(a), and Neu5Gc glycans on corneas

The corneal structure and cell morphology from TKO pigs and GTKO/CD46 pigs were not significantly different from those of WT pigs (Fig. 1A). The expression of αGal, Sd(a), and Neu5Gc antigens was examined using BSI-B4 lectin (to detect αGal), DBA lectin [to detect-Sd(a)], as well as chicken anti-Neu5Gc antibody (to detect Neu5Gc). The overall staining of αGal epitopes was low in the cornea with weak signals distributed in several keratocytes in the anterior-most part of the corneal stroma of WT pigs, whereas GTKO and TKO porcine keratocytes did not show any expression of the αGal epitopes (Fig. 1B). The expression of Sd(a) (Fig. 1C) and Neu5Gc antigens (Fig. 1D) was detected in keratocytes of the anterior stroma in WT pig corneas with weak diffuse expression in the stroma, which is consistent with a previous report[30]. The posterior corneal stroma and endothelium showed no expression of αGal (data not shown). As expected, there was no αGal expression in TKO or GTKO pigs, nor were Sd(a) antigen or Neu5Gc detected in TKO pigs (Fig. 1B– D).

1.

Representative images of histology and antigen expression of wildtype (WT) and triple gene knockout (TKO) corneal sections.

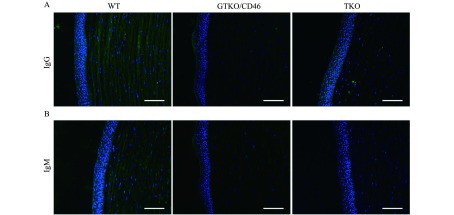

Human IgG/IgM binding to porcine corneas

To investigate the immunoreactivity of porcine corneas, the binding of human serum IgM and IgG to corneas was examined by immunofluorescence staining. Binding of IgG and IgM was mainly present in the corneal stroma from WT, GTKO/CD46 and TKO pigs. Compared to WT pig corneas, human IgM and IgG binding to TKO and GTKO/CD46 porcine corneas was significantly decreased (Fig. 2A & B). Surprisingly, the binding of IgG and IgM did not decrease in TKO pig corneas compared to GTKO pig corneas.

2.

IgM and IgG binding to WT and TKO corneas incubated with human serum.

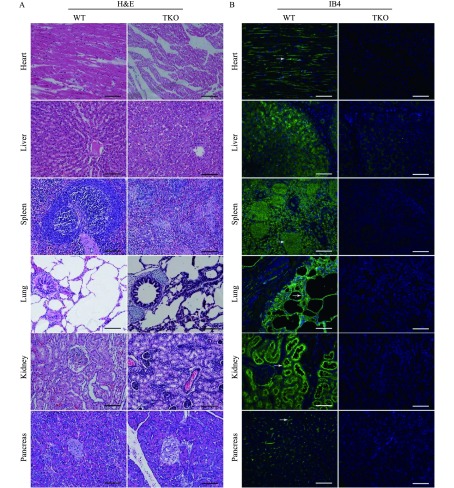

Expression of αGal, Sd(a), and Neu5Gc glycans in the heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney and pancreas

As with corneas, the tissue structure and cell morphology of the heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney and pancreas did not show significant difference between genetically modified pigs and WT pigs (Fig. 3A). The distributions of αGal, Neu5Gc, and Sd(a) antigens were then examined in those tissues from WT and TKO pigs by immunofluorescence. The results showed that all WT pig tissues had αGal (Fig. 3B), Sd (a) (Fig. 3C) and Neu5Gc antigens expressed (Fig. 3D). Tissue-specific distributions of these three glycans were clearly observed in different organs and tissues as revealed by relevant lectins or antibody staining. αGal, Sd(a) antigen, and Neu5Gc were expressed strongly in capillary endothelia and myolemma of the cardiac muscle. In livers, αGal was extensively distributed in hepatocytes and endothelia of vessels, and Sd(a) antigen and Neu5Gc were expressed strongly in the endothelia of capillaries and vessels. In spleen tissues, αGal and Sd(a) antigens were significant in lymphonoduli and the endothelia of trabecular arteries, while Neu5Gc was mainly found in the endothelia of trabecular arteries. In lung tissues, αGal, Sd(a) antigen, and Neu5Gc were noticeably expressed in pulmonary alveoli and endothelia of bronchioles. In kidney tissues, αGal was obvious in renal capsules and convoluted tubules, while Sd(a) antigen was strongly present in the renal mesenchyme. In pancreas tissues, αGal, Sd(a) antigen, and Neu5Gc were mainly scattered in the endothelia of capillaries and vessels. As expected, αGal, Neu5Gc, and Sd(a) glycans were not detected in the heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, and pancreas from TKO pigs.

3.

Representative images of histology and xenoantigen expression of WT and TKO heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, and pancreas tissue sections.

Human IgG/IgM binding in the heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, and pancreas

Human serum IgG (Fig. 4A) and IgM (Fig. 4B) binding assays were performed for the heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney and pancreas of TKO and WT pigs. Binding of IgM and IgG significantly decreased in TKO heart compared to WT heart (Fig. 4A & B). More IgG binding to WT heart was observed than IgM binding, but there was no significant difference between IgG and IgM binding in TKO heart (Fig. 4A & B). There was also significantly less IgM and IgG binding to TKO porcine lung and kidney tissues when incubated withhuman sera in parallel with WT porcine lung and kidney tissues (Fig. 4A & B). There was slightly greater IgG binding than IgM binding to WT porcine lung and kidney tissues; however, TKO porcine lung and kidney tissues did not show significant difference between IgG and IgM binding (Fig. 4A & B). Surprisingly, human serum IgG (Fig. 4A) and IgM (Fig. 4B) binding to TKO pig liver tissues slightly increased compared to WT controls. There was no significant difference in the pancreas and spleen between WT and TKO pig (Fig. 4A & B).

4.

Human IgM and IgG binding to the heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, and pancreas from WT and TKO pigs.

Discussion

Organs/tissues from non-human mammals are a potential solution to the shortage of human donor organs worldwide. Due to its similarity with humans, the pig has been studied as a donor for xenotransplantation. However, the most profound barrier in using pig organs/tissues for xenotransplantation is the destruction of xenografts by the host immunological system[13,29– 30]. Three identified pig antigens that can cause rejection to xenografts are αGal, Neu5Gc and Sd(a)[21]. To reduce human antibody response to pig tissues, these xenoantigens can be eliminated through genetic modification. Using the highly efficient CRISPR/Cas9 gene targeting system, GGTA1/CMAH/ β4GalNT2 triple gene knockout (TKO) pigs have been generated recently and shown significantly reduced human IgM and IgG binding to pericardium tissues[28]. In the present study, the expressions of αGal, Neu5Gc, and Sd(a) antigens in the TKO corneal tissues and solid organs (liver, lung, spleen, heart, and kidney) were determined by immunohistochemistry. The results indicate that the αGal, Neu5Gc and Sd(a) antigens are negative in the tissues and organs from TKO pigs. The human IgG/IgM binding to organs or tissues were also significantly reduced.

As the cornea is an avascular tissue, it seems to be an ideal material for xenografts. Hara et al reported that human IgG/IgM binding was significantly decreased in the pig corneal endothelial cells (pCEC) from GTKO/CD46 pigs compared to WT pCECs[31]. Surprisingly, transplantation of full-thickness GTKO/CD46 pig corneas into rhesus monkeys neither prolonged graft survival nor reduced antibody response compared with WT pig cornea[12]. In the present study, we found that the expression of Sd(a) antigen in the corneal tissue was stronger than that of αGal and Nue5Gc, indicating that Sd(a) might be a major antigen present on corneas. Therefore, this result might partly explain the failure of GTKO/CD46 porcine corneal xenotransplantation into non-human primates. Moreover, binding of human IgG and IgM did not decrease in TKO porcine corneas compared to GTKO/CD46 porcine corneas, suggesting that besides Sd(a) antigen, there still exist some major antigens in pig corneas.

Using relevant lectins or antibodies, we detected the expression of αGal, Neu5Gc, and Sd(a) antigens in different organs and tissues, such as heart, liver, lung, kidney, spleen, and pancreas. Immunofluorescence staining indicated that these three carbohydrate antigens were mostly found in WT porcine vascular endothelial cells of the tested organs. Tissue-specific distributions of these antigens were observed as αGal was strongly expressed in the kidney, and so was Sd(a) in the pancreas, and Neu5Gc in the heart. As anticipated, the expressions of αGal, Neu5Gc, and Sd(a) were absent in TKO pig tissues/organs (heart, liver, lung, kidney, spleen, and pancreas). Human serum IgG and IgM binding decreased in some TKO porcine tissues of heart, lung, and kidney, showing that eliminating the reactivity of preformed human antibodies with those tissues can be achieved by gene targeting. However, comparable levels of IgG and IgM binding were observed in the liver, spleen, and pancreas of TKO and WT pig, suggesting that other immunoreactive xenoanigens such as swine leukocyte antigens (SLA) maybe the dominant xenoantigens in those organs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81570402 & 31701283), the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFC1103701 & 2017YFC1103702), the Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Xenotransplantation (BM2012116), the Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen, the Fund for High Level Medical Discipline Construction of Shenzhen (2016031638), and the Shenzhen Foundation of Science and Technology (JCYJ20160229204849975 & GCZX2015043017281705).

Contributor Information

Haiyuan Yang, Email: hyyang@njmu.edu.cn.

Yifan Dai, Email: daiyifan@njmu.edu.

References

- 1.McGregor CGA, Byrne GW Porcine to human heart transplantation: is clinical application now appropriate? J Immunol Res. 2017;2017:2534653. doi: 10.1155/2017/2534653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel MS, Louras N, Vagefi PA Liver xenotransplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2017;22(6):535–540. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah JA, Patel MS, Elias N, et al Prolonged survival following pig-to-primate liver xenotransplantation utilizing exogenous coagulation factors and costimulation blockade. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(8):2178–2185. doi: 10.1111/ajt.2017.17.issue-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwase H, Kobayashi T Current status of pig kidney xenotransplantation. Int J Surg. 2015;23(Pt B):229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.07.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukui A, Yokoo T Kidney regeneration using developing xenoembryo. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2015;20(2):160–164. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilczek P, Lesiak A, Niemiec-Cyganek A, et al Biomechanical properties of hybrid heart valve prosthesis utilizing the pigs that do not express the galactose-α-1,3-galactose (α-Gal) antigen derived tissue and tissue engineering technique. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2015;26(1):5329. doi: 10.1007/s10856-014-5329-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laird C, Burdorf L, Pierson RN 3rd Lung xenotransplantation: a review. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2016;21(3):272–278. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sahara H, Watanabe H, Pomposelli T, et al Lung xenotransplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2017;22(6):541–548. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abalovich A, Matsumoto S, Wechsler CJ, et al Level of acceptance of islet cell and kidney xenotransplants by personnel of hospitals with and without experience in clinical xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2017;24(4):1–5. doi: 10.1111/xen.12315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper DKC, Matsumoto S, Abalovich A, et al Progress in clinical encapsulated islet xenotransplantation. Transplantation. 2016;100(11):2301–2308. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper DKC, Ekser B, Ramsoondar J, et al The role of genetically engineered pigs in xenotransplantation research. J Pathol. 2016;238(2):288–299. doi: 10.1002/path.4635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong X, Hara H, Wang Y, et al Initial study of 1,3- galactosyltransferase gene-knockout/CD46 pig full-thickness corneal xenografts in rhesus monkeys. Xenotransplantation. 2017;24(1):1–12. doi: 10.1111/xen.12282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ekser B, Li P, Cooper DKC Xenotransplantation: past, present, and future. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2017;22(6):513–521. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper DKC, Pierson RN 3rd, Hering BJ, et al Regulation of clinical xenotransplantation-time for a reappraisal. Transplantation. 2017;101(8):1766–1769. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higginbotham L, Mathews D, Breeden CA, et al Pre-transplant antibody screening and anti-CD154 costimulation blockade promote long-term xenograft survival in a pig-to-primate kidney transplant model. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22(3):221–230. doi: 10.1111/xen.12166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper DKC, Ezzelarab MB, Hara H Low anti-pig antibody levels are key to the success of solid organ xenotransplantation: But is this sufficient? Xenotransplantation. 2017;24(6):1–6. doi: 10.1111/xen.12360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai L, Kolber-Simonds D, Park KW, et al Production of alpha- 1,3-galactosyltransferase knockout pigs by nuclear transfer cloning. Science. 2002;295(5557):1089–1092. doi: 10.1126/science.1068228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dai Y, Vaught TD, Boone J, et al Targeted disruption of the alpha1, 3-galactosyltransferase gene in cloned pigs. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20(3):251–255. doi: 10.1038/nbt0302-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGregor CGA, Ricci D, Miyagi N, et al Human CD55 expression blocks hyperacute rejection and restricts complement activation in Gal knockout cardiac xenografts. Transplantation. 2012;93(7):686–692. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182472850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGregor C, Byrne G, Rahmani B, et al Physical equivalency of wild type and galactose α 1,3 galactose free porcine pericardium; a new source material for bioprosthetic heart valves. Acta Biomater. 2016;41:204–209. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohiuddin MM, Corcoran PC, Singh AK, et al B-cell depletion extends the survival of GTKO.hCD46Tg pig heart xenografts in baboons for up to 8 months. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(3):763–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03846.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen G, Qian H, Starzl T, et al Acute rejection is associated with antibodies to non-Gal antigens in baboons using Gal-knockout pig kidneys. Nat Med. 2005;11(12):1295–1298. doi: 10.1038/nm1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Byrne GW, Du Z, Stalboerger P, et al Cloning and expression of porcine 1,4 N-acetylgalactosaminyl transferase encoding a new xenoreactive antigen. Xenotransplantation. 2014;21(6):543–554. doi: 10.1111/xen.2014.21.issue-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee W, Hara H, Ezzelarab MB, et al Initial in vitro studies on tissues and cells from GTKO/CD46/NeuGcKO pigs. Xenotransplantation. 2016;23(2):137–150. doi: 10.1111/xen.2016.23.issue-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burlak C, Bern M, Brito AE, et al N-linked glycan profiling of GGTA1/CMAH knockout pigs identifies new potential carbohydrate xenoantigens. Xenotransplantation. 2013;20(5):277–291. doi: 10.1111/xen.2013.20.issue-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petersen B, Frenzel A, Niemann H Efficient generation of a triple knockout (GGTA1/CMAH/ASGR1) of xenorelevant genes in pig fibroblasts. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22(Suppl S1):S40. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Estrada JL, Martens G, Li P, et al Evaluation of human and non-human primate antibody binding to pig cells lacking GGTA1/CMAH/4GalNT2 genes. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22(3):194–202. doi: 10.1111/xen.2015.22.issue-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang RJ, Wang Y, Chen L, et al Reducing immunoreactivity of porcine bioprosthetic heart valves by genetically-deleting three major glycan antigens, GGTA1/4GalNT2/CMAH. Acta Biomater. 2018;72:196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang ZY, Martens GR, Blankenship RL, et al Eliminating xenoantigen expression on swine RBC. Transplantation. 2017;101(3):517–523. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amano S, Shimomura N, Kaji Y, et al Antigenicity of porcine cornea as xenograft. Curr Eye Res. 2003;26(6):313–318. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.26.5.313.15440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hara H, Koike N, Long C, et al Initial in vitro investigation of the human immune response to corneal cells from genetically engineered pigs . Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(8):5278–5286. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

![A: Tissue structures in different corneas were examined by H&E staining. B–D: Expression of αGal, Sd(a), and Neu5Gc antigens in WT, GTKO/ CD46, and TKO pig corneas were detected by immunofluorescence staining. The control group consisted of unstained tissues [for αGal and Sd (a)] or isotype control (chicken IgY for Neu5Gc), but were stained with DAPI. In WT porcine corneas, weak αGal-positive keratocytes were located at the anterior region of the corneal stroma (white arrows). In contrast, there was no expression of αGal in GTKO/CD46 and TKO corneas. In WT and GTKO/CD46 pig corneas, Sd(a) and Neu5Gc antigens were detected in the anterior cells of the epithelium (white arrows). In TKO pigs, Sd(a) and Neu5Gc antigens were seen in the cornea (Nuclei, blue; αGal, Neu5Gc, and Sd(a) antigens, green). Scale bar = 100 μm.](https://cdn.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/blobs/856e/6813527/e247553264a7/jbr-33-4-235-1.jpg)