This cohort study uses data from all persons born in Denmark from 1980 to 2000 and followed up for as many as 37 years to compare parental income and income mobility during childhood with the likelihood of offspring being diagnosed with schizophrenia after age 15 years.

Key Points

Question

How are parental income level and income mobility during childhood associated with subsequent risk for schizophrenia?

Findings

This Danish cohort study of more than 1 million persons found a dose-response association between increasing amount of time spent in low-income conditions and greater schizophrenia risk. Regardless of parental income level at birth, upward income mobility was associated with lower schizophrenia risk compared with downward mobility.

Meaning

Although causality cannot be assumed, this study’s findings suggest that enabling upward family income mobility during childhood may reduce subsequent schizophrenia incidence.

Abstract

Importance

Evidence linking parental socioeconomic position and offspring’s schizophrenia risk has been inconsistent, and how risk is associated with parental socioeconomic mobility has not been investigated.

Objective

To elucidate the association between parental income level and income mobility during childhood and subsequent schizophrenia risk.

Design, Setting, and Participants

National cohort study of all persons born in Denmark from January 1, 1980, to December 31, 2000, who were followed up from their 15th birthday until schizophrenia diagnosis, emigration, death, or December 31, 2016, whichever came first. Data analyses were from March 2018 to June 2019.

Exposure

Parental income, measured at birth year and at child ages 5, 10, and 15 years.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Hazard ratios (HRs) for schizophrenia were estimated using Cox proportional hazard regression. Cumulative incidence values (absolute risks) were also calculated.

Results

The cohort included 1 051 033 participants, of whom 51.3% were male. Of the cohort members, 7544 (4124 [54.7%] male) were diagnosed with schizophrenia during 11.6 million person-years of follow-up. There was an inverse association between parental income level and subsequent schizophrenia risk, with children from lower income families having especially elevated risk. Estimates were attenuated, but risk gradients remained after adjustment for urbanization, parental mental disorders, parental educational levels, and number of changes in child-parent separation status. A dose-response association was observed with increasing amount of time spent in low-income conditions being linked with higher schizophrenia risk. Regardless of parental income level at birth, upward income mobility was associated with lower schizophrenia risk compared with downward mobility. For example, children who were born and remained in the lowest income quintile at age 15 years had a 4.12 (95% CI, 3.71-4.58) elevated risk compared with the reference group, those who were born in and remained in the most affluent quintile, but even a rise from the lowest income quintile at birth to second lowest at age 15 years appeared to lessen the risk elevation (HR, 2.80; 95% CI, 2.46-3.17). On the contrary, for those born in the most affluent quintile, downward income mobility between birth and age 15 years was associated with increased risks of developing schizophrenia.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study’s findings suggest that parental income level and income mobility during childhood may be linked with schizophrenia risk. Although both causation and selection mechanisms could be involved, enabling upward income mobility could influence schizophrenia incidence at the population level.

Introduction

Socioeconomic risk gradients are well established in association with many common mental illnesses, such as depression and anxiety disorders, with children and adolescents from disadvantaged backgrounds being more likely to be affected.1 Evidence linking parental socioeconomic position (SEP) with schizophrenia risk in offspring is less consistent, however. With parental occupational status as a measure of SEP, earlier research has reported elevated schizophrenia risks among persons from higher vs lower socioeconomic position.2,3,4 Other, especially more recently published studies, have found greater risks linked with low parental occupational status5,6,7 as well as with parental unemployment8,9 and low income.8 Evidence from studies using parental educational attainment as a proxy for SEP was also mixed, with higher levels of parental education linked with both elevated8,10 and decreased schizophrenia risks.6 In addition, unlike with many other health outcomes1,11 wherein there is a continuous social gradient in disease risk, there has been little evidence thus far to suggest that such a gradient exists for schizophrenia, and a threshold effect has been postulated instead.7

Parental occupation, unemployment, and educational attainment level have commonly been used as indicators of parental SEP, whereas parental income has rarely been examined, partly owing to this variable being unavailable to researchers in most countries. In addition, parental SEP has often been measured at 1 time point only (eg, at birth),2,3,4,5,6,7 and it remains unclear whether and how risk of developing the disorder is modified by parental socioeconomic mobility during childhood. Using Danish national registry data, we conducted a comprehensive longitudinal analysis to explore links between parental income and income mobility during childhood and subsequent schizophrenia risks. To our knowledge, no published studies have previously investigated such links. Unlike parental educational attainment level or years of completed education, which can never decrease, income can fluctuate considerably in both directions over time.12 By examining changes in relative terms across the parental income distribution, instead of changes in occupational status, we also overcame potential issues with occupational classifications associated with varying labor market dynamics for different birth cohorts (eg, the reduction of unskilled or manual occupations).12 Furthermore, income has been shown to have a cumulative effect on physical and psychological functioning.13 Parental income was measured during birth year and at ages 5 years (early childhood), 10 years (middle childhood), and 15 years (adolescence). The study addressed the following research questions:

What are the associations between parental income measured at each of these 4 ages and risk of developing schizophrenia after the 15th birthday?

How does duration of time spent in financially disadvantageous vs more affluent conditions modify risk?

How are changes in parental income level between birth and age 15 years associated with risk?

Methods

Study Population

Since 1968, all residents of Denmark have been assigned a unique personal identification number, allowing individual-level linkage across a large array of national registers. We used the Danish Civil Registration System, which includes demographic details and links to parents as well as continual updates on place of residence and vital status.14 Our study population included all individuals born in Denmark between January 1, 1980, and December 31, 2000, with 2 Danish-born parents, who were alive and living in Denmark at their 15th birthday. These parameters delineated a study cohort of 1 051 033 persons, 539 596 (51.3%) of whom were male. Data analysis was conducted from March 2018 to June 2019. The Danish Data Protection Agency approved the study, with data access agreed by the Danish Health Data Authority and Statistics Denmark. Because it was based exclusively on registry data, according to the Danish Act on Processing of Personal Data, Section 10, informed written consent from cohort members was not required.

Parental Income Measurement

Information about maternal and paternal gross income, which includes salary, entrepreneurial income, capital income, public transfer payments, and pensions, was obtained from the Integrated Database for Labour Market Research.15 Paternal and maternal income were measured in the child’s birth year (age 0) and at ages 5, 10, and 15 years. Parental income was calculated by adding maternal and paternal income, and the sums were then placed into quintiles in the national income distribution for that calendar year, with quintile 1 representing the lowest income and quintile 5 the highest. To explore the associations between schizophrenia risk and the duration of time spent living in more affluent vs less affluent conditions during childhood, we calculated a cumulative parental income scale by adding the parental income quintiles measured at each of the 4 ages. The scale ranged from 4 to 20, and it indicated both relative parental income levels and their duration between birth and the child’s 15th birthday. Further information on the parental income scale is provided in eAppendix 1 in the Supplement. The scale was developed for another of recently published Danish registry studies.16

Ascertainment of Schizophrenia Cases

The study cohort was linked to the Psychiatric Central Research Register,17 which captures information on all inpatient psychiatric admissions from 1969, and all outpatient and emergency unit visits from 1995. Cohort members were classified as having schizophrenia (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision diagnosis code F20) if they had been admitted to a psychiatric hospital, received outpatient psychiatric care, or attended a psychiatric emergency unit with this diagnosis. The date of diagnosis was defined as the first day of first contact with a schizophrenia diagnosis.

Covariates

History of parental mental disorders was also obtained from the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register.17 Paternal and maternal educational attainment was extracted from the Population Education Register.18 Information on degree of urbanization at cohort members’ place of residence in their year of birth,19 as well as the total number of changes in child-parent separation status between birth and 15th birthday (according to residential addresses),20 was acquired from the Civil Registration System. Further information on covariates is available in eAppendix 2 in the Supplement.

Statistical Analysis

Cohort members were followed up from their 15th birthday until their first diagnosis of schizophrenia, date of death, emigration, or December 31, 2016, whichever came first. The maximum length of follow-up was thus 22 complete years, up to the 37th birthday for cohort members born on January 1, 1980. Relative risks of schizophrenia, reported as hazard ratios (HRs), were estimated using Cox proportional hazard regression models adjusted for sex, birth year, and time-varying (ie, time-dependent) calendar year period. Further adjustments for history of parental psychiatric disorder, parental education, urbanicity at birth, and number of changes in child-parental separation status were also made. Birth year– and sex-adjusted cumulative incidence (absolute risk) of schizophrenia according to parental income quintiles was estimated using competing-risks regression, with death and emigration being treated as competing events.21 Statistical significance was set at 2-sided P = .05. Analyses were performed using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp).

Results

Associations Between Parental Income at Varying Stages of Childhood and Later Risk of Developing Schizophrenia

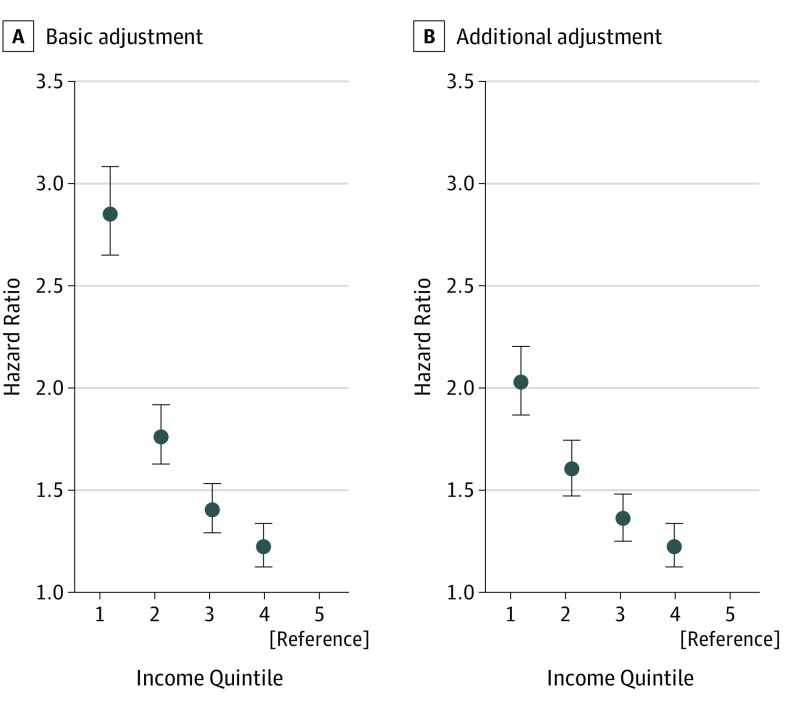

Of the 1 051 033 members of the cohort, 539 596 (51.3%) were male. Cohort members were followed up across 11.6 million person-years in aggregate, and 7544 individuals (0.72%) were diagnosed with schizophrenia during the observation period. Of those diagnosed with schizophrenia, 4124 (54.7%) were male. Sociodemographic information (eTable 1 in the Supplement) and incidence rates stratified by the covariates (eTable 2 in the Supplement) are reported in the Supplement. The association between parental income quintile measured at age 15 years and subsequent risk of developing schizophrenia, adjusted for sex, birth year, and time-varying calendar year period, is shown in Figure 1A. The highest income stratum (quintile 5) was used as the reference category for relative risk estimation. An inverse association between parental income quintile and schizophrenia risk was observed, with lower parental income levels associated with greater risk for developing the disorder. The associations were nonlinear, with risk disproportionately elevated among cohort members in the families with the lowest income (quintile 1) (HR, 2.86; 95% CI, 2.65-3.08). When further adjustments were made for history of parental mental disorder, parental educational attainment level, degree of urbanization, and number of changes in child-parent separation status, HRs were attenuated, particularly in relation to quintile 1 (HR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.87-2.20) (Figure 1B). The graded risk patterns remained, however. Similar risk patterns were observed for parental income measured during birth year and at ages 5 and 10 years (eFigure and eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Figure 1. Hazard Ratios (HRs) of Schizophrenia Risk According to Parental Income Quintiles at Age 15 Years.

A, In the basic adjustment, HRs are adjusted for sex, birth year, and calendar time. B, In the additional adjustment, HRs are adjusted for sex, birth year, calendar time, parental mental disorders, parental educational attainment level, degree of urbanicity at birth, and number of changes in child-parental separation status. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

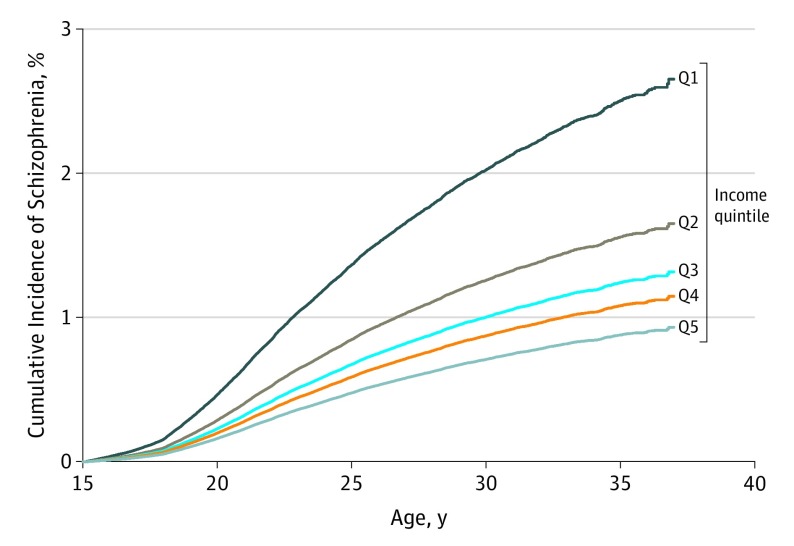

Figure 2 shows absolute risks, expressed as cumulative incidence percentage values adjusted for birth year and sex, of developing schizophrenia between ages 15 and 37 years according to parental income levels at age 15 years. The lower the parental income level at age 15 years, the greater the subsequent absolute risk for the disorder. For example, those from the lowest income quintile families at age 15 years had a 2.7% (95% CI, 2.4%-2.8%) risk of being diagnosed with schizophrenia by age 37 years compared with 0.9% (95% CI, 0.8%-1.1%) for those in the most affluent quintile.

Figure 2. Cumulative Incidence of Schizophrenia by Parental Income Quintiles (Qs) at Age 15 Years.

The cumulative incidence percentage value measures the risk (probability) of developing schizophrenia before a given age. Quintile 1 is the lowest income quintile, and Q5 is the highest income quintile. The model is adjusted for sex (reference, male) and birth year (reference, 1980).

Risk Patterns Associated With Duration of Parental Income Levels During Childhood

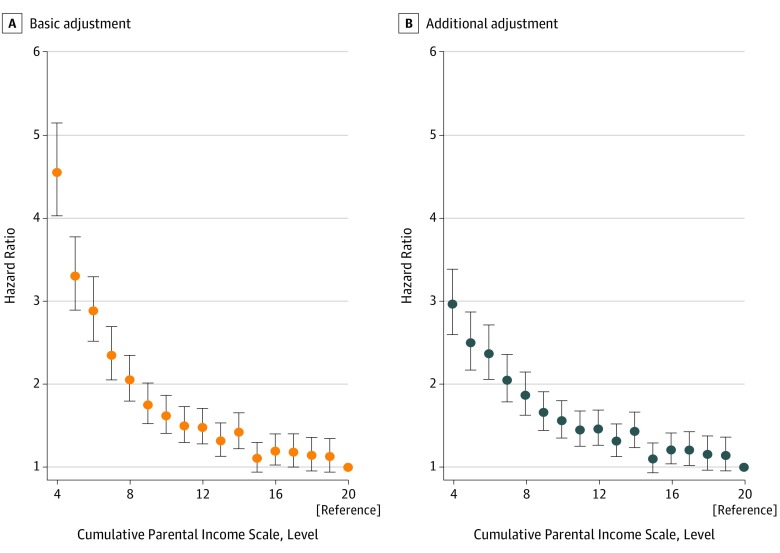

The association between cumulative parental income scale and schizophrenia risk, expressed as HRs and adjusted for sex, birth year, and calendar time, is shown in Figure 3A and eTable 4 in the Supplement. A maximum score of 20, which indicates parental income consistently in the highest quintile (5), was used as the reference category for HR estimation. The figure shows that children whose families remained in the lowest income quintile throughout childhood (score = 4) had a 4.60 (95% CI, 4.07-5.20) elevated risk of subsequently being diagnosed with schizophrenia compared with individuals who experienced the greatest level of affluence throughout their upbringing. In general, the longer a child remained in more economically disadvantaged conditions, as indicated by a lower parental income score, the greater the subsequent schizophrenia risk, with those who were born in and remained in the least affluent quintile having disproportionately greater risk. When the models were further adjusted for parental mental disorder, parental educational attainment level, degree of urbanization, and number of changes in child-parent separation status (Figure 3B; eTable 4 in the Supplement), elevated risk associated with longer duration of low income (as indicated by the lower end of the income scale) was attenuated. Overall, the dose-response association between parental income scale and schizophrenia risk remained after adjustment for these covariates.

Figure 3. Hazard Ratios (HRs) of Schizophrenia Risk by Cumulative Parental Income Scale During Childhood.

The parental income scale represents relative parental income levels and their duration between birth and 15th birthday. The minimum possible score of 4 represents parental income being in the lowest level, quintile 1, across all 4 age points (ie, at birth, and at ages 5, 10, and 15 years). A maximum score of 20, the reference category for HR estimation (HR = 1), represents parental income being consistently in the highest level, quintile 5. A, In the basic adjustment, HRs are adjusted for sex, birth year, and calendar time. B, In the additional adjustment, HRs are adjusted for sex, birth year, calendar time, parental mental disorders, parental educational attainment level, degree of urbanicity at birth, and number of changes in child-parental separation status. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

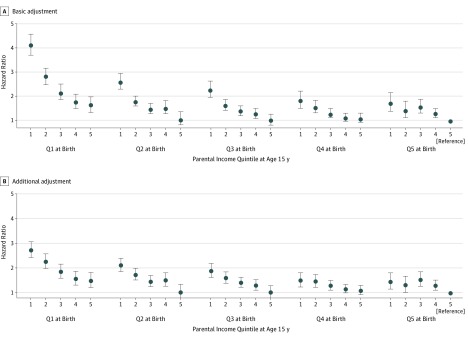

Schizophrenia Risk According to Parental Income Mobility Between Birth and Age 15 Years

Descriptive information pertaining to changes in parental income level between birth and age 15 years is shown in eTable 5 in the Supplement. Figure 4A and eTable 6 in the Supplement present relative risks for developing schizophrenia according to changes in parental income level between the 2 ages, adjusted for sex, birth year, and calendar time. Compared with persons who were born in and who remained in quintile 5 (the most affluent quintile, the reference group) at age 15 years, most other parental income level changes were associated with elevated schizophrenia risk. In general, however, irrespective of parental income level at birth, having a higher income level at age 15 years (ie, being upwardly mobile), was associated with lower risks of developing the disorder, whereas downward mobility was generally linked with higher risks. Being in the lowest parental income quintile at birth and remaining in quintile 1 at age 15 years was associated with the highest risk (HR, 4.12; 95% CI, 3.71-4.58), but even a rise in income from quintile 1 at birth to quintile 2 at age 15 years appeared to considerably lessen the risk elevation (HR, 2.80; 95% CI, 2.46-3.17). The risk for individuals whose parental income rose from quintile 1 to quintile 5 between birth and age 15 years (ie, the most upwardly mobile group) was even further reduced (HR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.32-1.97). When the models were further adjusted for parental mental disorder, parental educational level, degree of urbanization, and number of changes in child-parent separation status, the adjusted HRs were attenuated, although similar risk patterns remained (Figure 4B and eTable 6 in the Supplement).

Figure 4. Hazard Ratios (HRs) of Schizophrenia Risk According to Parental Income Mobility Between Birth and Age 15 Years.

The reference group for HR estimation is parental income quintile 5 at both birth year and at age 15 years (HR = 1). A, In the basic adjustment, HRs are adjusted for sex, birth year, and calendar time. B, In the additional adjustment, HRs are adjusted for sex, birth year, calendar time, parental mental disorders, parental educational attainment level, degree of urbanicity at birth, and number of changes in child-parental separation status. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

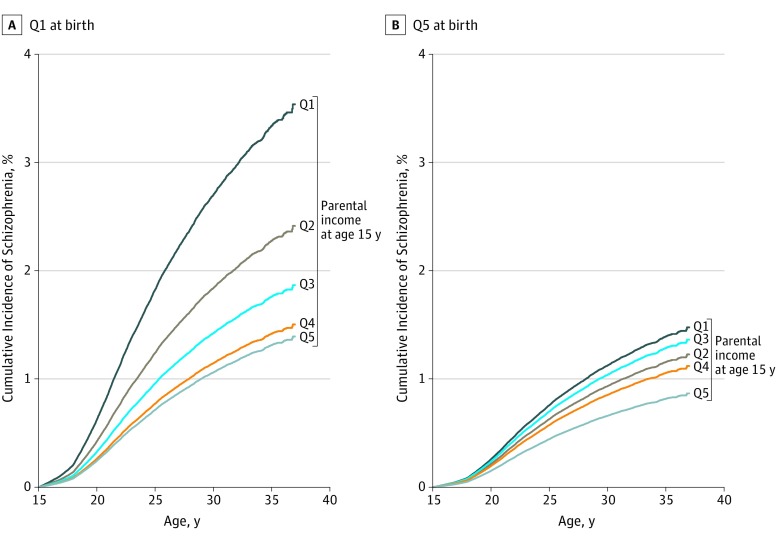

We also estimated absolute risks for developing schizophrenia between ages 15 and 37 years associated with parental income mobility between birth year and age 15 years. These estimates, expressed as cumulative incidence percentage values, are shown in Figure 5 for the lowest (quintile 1) and the highest (quintile 5) parental income levels at birth. Although persons born in the lowest income quintile families generally showed much higher risks of developing the disorder than those born in the most affluent quintile, upward income mobility between birth and age 15 was associated with greatly reduced absolute risks. For example, persons who were in the lowest parental income quintile at birth and who remained in this quintile on their 15th birthday had a 3.5% (95% CI, 3.3%-3.8%) risk of developing the disorder by age 37 years, but moving from quintile 1 (lowest) at birth to quintile 2 (second lowest) at age 15 was linked with a lower absolute risk of 2.4% (95% CI, 2.1%-2.8%). Similarly, upward mobility from quintile 1 at birth to quintile 3, 4, or 5 at age 15 years was associated with further reductions in risk. Conversely, for those born in the most affluent quintile, experiencing downward income mobility between birth and age 15 years was associated with an increased risk of developing schizophrenia. However, the risks were not as great as for persons born in quintile 1, except for those whose parental income was in quintile 5 at birth but had dropped to quintile 1 at age 15. The schizophrenia risk for this most downwardly mobile group was 1.5% (95% CI, 1.0%-2.2%), which was comparable with the risk of 1.4% (95% CI, 1.0%-1.9%) for the most upwardly mobile group (ie, those whose parental income rose from quintile 1 to 5 between birth and 15th birthday).

Figure 5. Cumulative Incidence of Schizophrenia Associated With the Lowest (Quintile 1 [Q1]) and the Highest (Q5) Parental Income Levels in the Year of Birth.

The cumulative incidence percentage value measures the risk (probability) of developing schizophrenia before a given age. Models are adjusted for sex (reference, male) and birth year (reference, 1980).

Discussion

Main Findings

In a national cohort of more than 1 million Danish persons, we observed a graded association between parental income during childhood and subsequent risk of developing schizophrenia. Cohort members from families in the lowest income quintile were more likely to be diagnosed with the disorder, even after adjustment for parental mental illness, degree of urbanization, parental educational attainment level, and number of changes in child-parent separation status. A dose-response association was observed, with increasing amount of time spent living in low-income conditions during childhood associated with greater subsequent schizophrenia risk. Regardless of the parental income level at birth, upward income mobility between birth and age 15 years was generally associated with a lower risk of developing schizophrenia; on the contrary, downward mobility predicted higher risks.

Existing Evidence and Interpretations

Income was rarely used as an indicator of parental SEP in previous studies investigating the link between childhood SEP and schizophrenia risk. Parental SEP has also mostly been measured at a single time point only.6,7,8,9 A national Swedish registry study examining family income trajectories during childhood reported that children from families with consistently low or declining levels of income were at greater risk of subsequently developing psychotic disorders than those from the most affluent backgrounds.22 Our study has found that risks of developing schizophrenia were modified by downward and upward parental income mobility. Both studies demonstrated the importance of considering childhood socioeconomic environment longitudinally rather than at a single time point. Our findings also concur with those reported from studies in which cumulative exposure to low income in childhood or in adulthood was associated with poorer physical and psychological outcomes.13,16

With parental occupational status or parental educational level used as indicators of SEP, some earlier studies reported a link between higher parental SEP and elevated schizophrenia risk.2,3,4,10 Although evidence from more recent studies suggests the opposite,6,7,8,9 it remained unclear whether a continuous socioeconomic gradient, as opposed to a threshold effect, exists.7 Using parental income as a measure of childhood SEP, we showed a clear gradient between parental income level and subsequent risk of developing the disorder. Individuals in the lowest parental income quintile were at disproportionately greater risk, especially those who remained so throughout their childhood. The contrasting findings could partly be attributed to examination of parental income rather than parental occupational status7 as a measure of SEP. It is also possible that parental income is a more sensitive marker than occupational status in capturing a multitude of childhood determinants of schizophrenia risk.

Schizophrenia is known to run in families,23 and risk is also raised among those living in a more urbanized environment.19 In our study, HRs were attenuated but the risk patterns remained essentially similar after adjustment for the potential confounding effects of parental history of mental disorders and degree of urbanization, as well as for parental educational attainment level and number of changes in child-parent separation status. There are a number of plausible mechanisms. Theory of social causation postulates that exposure to chronic stress caused by lack of socioeconomic resources explains why growing up in a more deprived environment is associated with worse health outcomes.24,25 Parental income at birth is likely to also be an indicator of environmental exposures during pregnancy. Maternal stress,26 maternal infections,27 and obstetric complications28 are known to influence early neurodevelopment associated with increased schizophrenia risk, and these risk factors are more common among mothers of lower SEP.29,30,31 In addition to financial hardship, children from poor families are more likely than those from affluent backgrounds to experience other familial difficulties such as physical and emotional conflicts,32 raising the risk of child abuse, which has been associated with increased risk for subsequent psychosis.33 Psychosocial risk factors are known to aggregate in families of lower SEP,34 with cumulative adverse effects on physical and mental health.35,36 Thus, low parental income likely captures a multitude of familial and environmental risk factors linked with schizophrenia. Our study’s findings suggest that risks for developing schizophrenia may be modified by parental income dynamics. Better physical and social environments and enhanced psychosocial well-being associated with improved familial financial resources may contribute to reducing the elevated schizophrenia risks observed, and the converse appears to be the case for downward mobility.37 Causality, however, cannot be inferred from our findings, which could also be attributed to social selection, explained by factors that influence both parents’ income mobility and their children’s vulnerability to developing schizophrenia. One example is parental mental ill health.38 Although we have adjusted for history of parental psychiatric illness, any untreated mental disorders or those treated in primary care only could not be accounted for. Caring for children who have prodromal syndromes prior to being diagnosed with schizophrenia may also adversely affect parental income during childhood (eg, parents having to give up work or change from full-time to part-time employment); therefore, reverse causality cannot be ruled out.39 In summary, rather than to elucidate the independent association of schizophrenia diagnosis with parental income per se, we conceptualized income as a marker for a range of financial and nonmaterial familial conditions associated with schizophrenia risk.

Strengths and Limitations

Use of interlinked Danish national registers provided rich information for the entire population, including information on parental income. Danish psychiatric hospitals and outpatient facilities are public and free of charge, so access is unlikely to be tied to financial resources. All admissions and discharges are recorded. By including only persons born in Denmark to 2 Danish-born parents, we controlled for the confounding influences on schizophrenia risk associated with immigration.40

Our study also has its limitations. Although schizophrenia diagnosis in the Psychiatric Central Research Register has high diagnostic validity, a small percentage of cases might have been mistakenly registered as schizophrenia when a different psychiatric diagnosis was given.41 In our study, the maximum age of follow-up was the 37th birthday and, although incidence rates of schizophrenia for both sexes are known to peak in the early 20s, men have higher rates of diagnosis than women between the ages of 20 and 50 years.42 Furthermore, in addition to parental mental disorders that had not been treated in secondary care, we also lacked information on psychosocial factors that could partially explicate the association between parental income during childhood and later schizophrenia risk.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that parental income level during childhood and family income mobility between a child’s birth and 15th birthday may be associated with schizophrenia risk. Although the causal mechanisms remain unclear, enabling upward income mobility could play a key role in improving mental health at the population level.

eAppendix 1. Further Information on Parental Income Scale

eAppendix 2. Further Information on Covariates

eTable 1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Cohort Members

eTable 2. Number of Cases and Incidence Rates of Cohort Members Diagnosed With Schizophrenia During Follow-up Stratified by the Covariates

eTable 3. Hazard Ratios of Schizophrenia Risk According to Parental Income Quintiles During Birth-Year and at Ages 5, 10, and 15 Years: Basic and Additional Adjustments

eTable 4. Hazard Ratios of Schizophrenia Risk by Cumulative Parental Income Scale During Childhood: Basic and Additional Adjustments

eTable 5. Number (and Percentages) of Cohort Members by Parental Income Changes Between Birth-Year and Age 15 Years

eTable 6. Hazard Ratios of Schizophrenia Risk According to Parental Income Mobility Between Birth-Year and Age 15 Years: Basic and Additional Adjustments

eFigure. Hazard Ratios of Schizophrenia Risk According to Parental Income Quintiles During Birth-Year and at Ages 5, 10, and 15 Years: Basic and Additional Adjustments

eReferences.

References

- 1.World Health Organization, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation Social Determinants of Mental Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mäkikyrö T, Isohanni M, Moring J, et al. Is a child’s risk of early onset schizophrenia increased in the highest social class? Schizophr Res. 1997;23(3):245-252. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(96)00119-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Timms D. Gender, social mobility and psychiatric diagnoses. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46(9):1235-1247. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)10052-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mulvany F, O’Callaghan E, Takei N, Byrne M, Fearon P, Larkin C. Effect of social class at birth on risk and presentation of schizophrenia: case-control study. BMJ. 2001;323(7326):1398-1401. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7326.1398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castle DJ, Scott K, Wessely S, Murray RM. Does social deprivation during gestation and early life predispose to later schizophrenia? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1993;28(1):1-4. doi: 10.1007/BF00797825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Werner S, Malaspina D, Rabinowitz J. Socioeconomic status at birth is associated with risk of schizophrenia: population-based multilevel study. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(6):1373-1378. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corcoran C, Perrin M, Harlap S, et al. Effect of socioeconomic status and parents’ education at birth on risk of schizophrenia in offspring. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44(4):265-271. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0439-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrne M, Agerbo E, Eaton WW, Mortensen PB. Parental socio-economic status and risk of first admission with schizophrenia: a Danish national register based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39(2):87-96. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0715-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wicks S, Hjern A, Gunnell D, Lewis G, Dalman C. Social adversity in childhood and the risk of developing psychosis: a national cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(9):1652-1657. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malama IM, Papaioannou DJ, Kaklamani EP, Katsouyanni KM, Koumantaki IG, Trichopoulos DV. Birth order sibship size and socio-economic factors in risk of schizophrenia in Greece. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;152:482-486. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.4.482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marmot M, Goldblatt P, Allen J, et al. Fair society, healthy lives: the Marmot review. http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review. Published 2010. Accessed June 14, 2019.

- 12.Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, Lynch JW, Davey Smith G. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(1):7-12. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.023531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lynch JW, Kaplan GA, Shema SJ. Cumulative impact of sustained economic hardship on physical, cognitive, psychological, and social functioning. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(26):1889-1895. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712253372606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):22-25. doi: 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petersson F, Baadsgaard M, Thygesen LC. Danish registers on personal labour market affiliation. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):95-98. doi: 10.1177/1403494811408483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mok PLH, Antonsen S, Pedersen CB, et al. Family income inequalities and trajectories through childhood and self-harm and violence in young adults: a population-based, nested case-control study. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3(10):e498-e507. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30164-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB. The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):54-57. doi: 10.1177/1403494810395825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen VM, Rasmussen AW. Danish Education Registers. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):91-94. doi: 10.1177/1403494810394715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vassos E, Agerbo E, Mors O, Pedersen CB. Urban-rural differences in incidence rates of psychiatric disorders in Denmark. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208(5):435-440. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.161091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paksarian D, Eaton WW, Mortensen PB, Merikangas KR, Pedersen CB. A population-based study of the risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder associated with parent-child separation during development. Psychol Med. 2015;45(13):2825-2837. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715000781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersen PK, Geskus RB, de Witte T, Putter H. Competing risks in epidemiology: possibilities and pitfalls. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(3):861-870. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Björkenstam E, Cheng S, Burström B, Pebley AR, Björkenstam C, Kosidou K. Association between income trajectories in childhood and psychiatric disorder: a Swedish population-based study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71(7):648-654. doi: 10.1136/jech-2016-208513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB, Westergaard T, et al. Effects of family history and place and season of birth on the risk of schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(8):603-608. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902253400803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dohrenwend BP, Levav I, Shrout PE, et al. Socioeconomic status and psychiatric disorders: the causation-selection issue. Science. 1992;255(5047):946-952. doi: 10.1126/science.1546291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turner RJ, Wheaton B, Lloyd DA. The epidemiology of social stress. Am Sociol Rev. 1995;60(1):104-125. doi: 10.2307/2096348 6040686 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khashan AS, Abel KM, McNamee R, et al. Higher risk of offspring schizophrenia following antenatal maternal exposure to severe adverse life events. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(2):146-152. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khandaker GM, Zimbron J, Lewis G, Jones PB. Prenatal maternal infection, neurodevelopment and adult schizophrenia: a systematic review of population-based studies. Psychol Med. 2013;43(2):239-257. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dalman C, Allebeck P, Cullberg J, Grunewald C, Köster M. Obstetric complications and the risk of schizophrenia: a longitudinal study of a national birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(3):234-240. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.3.234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen SKG, Berens AE, Nelson CA III. Effects of poverty on interacting biological systems underlying child development. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2017;1(3):225-239. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(17)30024-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Owen MJ, Sawa A, Mortensen PB. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2016;388(10039):86-97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01121-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker SP, Wachs TD, Grantham-McGregor S, et al. Inequality in early childhood: risk and protective factors for early child development. Lancet. 2011;378(9799):1325-1338. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60555-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Risky families: family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol Bull. 2002;128(2):330-366. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.2.330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Varese F, Smeets F, Drukker M, et al. Childhood adversities increase the risk of psychosis: a meta-analysis of patient-control, prospective- and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(4):661-671. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evans GW, Li D, Whipple SS. Cumulative risk and child development. Psychol Bull. 2013;139(6):1342-1396. doi: 10.1037/a0031808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hakulinen C, Pulkki-Råback L, Elovainio M, et al. Childhood psychosocial cumulative risks and carotid intima-media thickness in adulthood: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Psychosom Med. 2016;78(2):171-181. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elovainio M, Pulkki-Råback L, Hakulinen C, et al. Childhood and adolescence risk factors and development of depressive symptoms: the 32-year prospective Young Finns follow-up study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(11):1109-1117. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-205352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allardyce J, Boydell J. Review: the wider social environment and schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(4):592-598. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sareen J, Afifi TO, McMillan KA, Asmundson GJG. Relationship between household income and mental disorders: findings from a population-based longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(4):419-427. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marquis GS, Habicht JP, Lanata CF, Black RE, Rasmussen KM. Association of breastfeeding and stunting in Peruvian toddlers: an example of reverse causality. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26(2):349-356. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.2.349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cantor-Graae E, Pedersen CB, McNeil TF, Mortensen PB. Migration as a risk factor for schizophrenia: a Danish population-based cohort study. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:117-122. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.2.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uggerby P, Østergaard SD, Røge R, Correll CU, Nielsen J. The validity of the schizophrenia diagnosis in the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register is good. Dan Med J. 2013;60(2):A4578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pedersen CB, Mors O, Bertelsen A, et al. A comprehensive nationwide study of the incidence rate and lifetime risk for treated mental disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):573-581. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Further Information on Parental Income Scale

eAppendix 2. Further Information on Covariates

eTable 1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Cohort Members

eTable 2. Number of Cases and Incidence Rates of Cohort Members Diagnosed With Schizophrenia During Follow-up Stratified by the Covariates

eTable 3. Hazard Ratios of Schizophrenia Risk According to Parental Income Quintiles During Birth-Year and at Ages 5, 10, and 15 Years: Basic and Additional Adjustments

eTable 4. Hazard Ratios of Schizophrenia Risk by Cumulative Parental Income Scale During Childhood: Basic and Additional Adjustments

eTable 5. Number (and Percentages) of Cohort Members by Parental Income Changes Between Birth-Year and Age 15 Years

eTable 6. Hazard Ratios of Schizophrenia Risk According to Parental Income Mobility Between Birth-Year and Age 15 Years: Basic and Additional Adjustments

eFigure. Hazard Ratios of Schizophrenia Risk According to Parental Income Quintiles During Birth-Year and at Ages 5, 10, and 15 Years: Basic and Additional Adjustments

eReferences.