Key Points

Question

Does an association exist between risk of lung cancer and habitual intakes of dietary fiber (the main source of prebiotics) or yogurt (a probiotic food)?

Findings

In this pooled analysis of more than 1.44 million individuals from the United States, Europe, and Asia, high intakes of dietary fiber or yogurt were individually associated with reduced risk of lung cancer, independent of all known risk factors. A potential synergistic association of fiber and yogurt consumption with lung cancer risk was also observed.

Meaning

Dietary fiber and yogurt may be individually and jointly associated with reduced risk of lung cancer.

Abstract

Importance

Dietary fiber (the main source of prebiotics) and yogurt (a probiotic food) confer various health benefits via modulating the gut microbiota and metabolic pathways. However, their associations with lung cancer risk have not been well investigated.

Objective

To evaluate the individual and joint associations of dietary fiber and yogurt consumption with lung cancer risk and to assess the potential effect modification of the associations by lifestyle and other dietary factors.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This pooled analysis included 10 prospective cohorts involving 1 445 850 adults from studies that were conducted in the United States, Europe, and Asia. Data analyses were performed between November 2017 and February 2019. Using harmonized individual participant data, hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for lung cancer risk associated with dietary fiber and yogurt intakes were estimated for each cohort by Cox regression and pooled using random-effects meta-analysis.

Participants who had a history of cancer at enrollment or developed any cancer, died, or were lost to follow-up within 2 years after enrollment were excluded.

Exposures

Dietary fiber intake and yogurt consumption measured by validated instruments.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Incident lung cancer, subclassified by histologic type (eg, adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and small cell carcinoma).

Results

The analytic sample included 627 988 men, with a mean (SD) age of 57.9 (9.0) years, and 817 862 women, with a mean (SD) age of 54.8 (9.7) years. During a median follow-up of 8.6 years, 18 822 incident lung cancer cases were documented. Both fiber and yogurt intakes were inversely associated with lung cancer risk after adjustment for status and pack-years of smoking and other lung cancer risk factors: hazard ratio, 0.83 (95% CI, 0.76-0.91) for the highest vs lowest quintile of fiber intake; and hazard ratio, 0.81 (95% CI, 0.76-0.87) for high vs no yogurt consumption. The fiber or yogurt associations with lung cancer were significant in never smokers and were consistently observed across sex, race/ethnicity, and tumor histologic type. When considered jointly, high yogurt consumption with the highest quintile of fiber intake showed more than 30% reduced risk of lung cancer than nonyogurt consumption with the lowest quintile of fiber intake (hazard ratio, 0.67 [95% CI, 0.61-0.73] in total study populations; hazard ratio, 0.69 [95% CI, 0.54-0.89] in never smokers), suggesting potential synergism.

Conclusions and Relevance

Dietary fiber and yogurt consumption was associated with reduced risk of lung cancer after adjusting for known risk factors and among never smokers. Our findings suggest a potential protective role of prebiotics and probiotics against lung carcinogenesis.

This pooled analysis from 10 cohort studies that included more than 1.4 million participants evaluates whether an association exists between risk of lung cancer and the habitual consumption of dietary fiber (the main source of prebiotics) or yogurt (a probiotic food).

Introduction

Prebiotics and probiotics have attracted increasing attention owing to their roles in modulating the gut microbiota and their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties.1,2,3 Prebiotics, typically high in fiber-rich foods, are nondigestible compounds that can be fermented by gut microbiota and also modulate gut microbiota,4 while probiotics are living microorganisms, commonly included in yogurt, that can improve the composition or function of gut microbiota to bring health benefits to the host.5 Epidemiologic studies have assessed dietary fiber and yogurt, the main sources of prebiotics and probiotics in human diets, and have reported associations of yogurt or fiber with reduced risks of various diseases, including metabolic disorders,6,7 cardiovascular diseases,8,9 gastrointestinal cancers,10,11,12 and premature death.8,13 Recently, it has been shown that certain gut microbes are involved in lung inflammation,14 suggesting a potential novel role of dietary fiber and yogurt against lung disease.

Several cohort studies have linked dietary fiber intake to enhanced lung function15 and reduced risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)16,17,18 and of deaths from respiratory diseases.13 Prospective studies have also shown that fiber-rich, plant-based dietary patterns and fruit/vegetable consumption are significantly associated with decreased risk of lung cancer.19,20,21 However, direct evidence linking dietary fiber intake to lung cancer risk is scarce. The UK Million Women Study showed no association between dietary fiber and lung cancer risk among female never smokers.22 For yogurt consumption, a recent meta-analysis that included 2 cohort studies and 3 case-control studies reported a nonsignificant inverse association with lung cancer risk.23 Currently, no epidemiologic studies have examined the potential synergistic association of fiber and yogurt (ie, prebiotics and probiotics) with lung cancer risk.

Herein, we assess the associations of dietary fiber and yogurt intakes with lung cancer risk in a pooled analysis of more than 1.44 million individuals from the United States, Europe, and Asia. We evaluated the potential fiber or yogurt association with lung cancer among all participants and by sex, race/ethnicity, and tumor histologic type. We further assessed potential modifications of any associations by lifestyle and other dietary factors (eg, smoking status and saturated fat intake). Finally, we assessed the joint association of dietary fiber and yogurt consumption with lung cancer risk.

Methods

Study Populations

This study, performed from November 2017 to February 2019, analyzed deidentified, individual participant data from a lung cancer pooling project that included 10 prospective cohort studies conducted in the United States, Europe, and Asia.24,25 Participating cohorts included the National Institutes of Health–AARP Diet and Health Study (NIH-AARP), Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS), Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), Iowa Women’s Health Study (IWHS), Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (PLCO), Southern Community Cohort Study (SCCS), Vitamins and Lifestyle Study (VITAL), European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC), Shanghai Men’s Health Study (SMHS), and Shanghai Women’s Health Study (SWHS). All studies were approved by the institutional review boards and ethics committees of the hosting institutes.

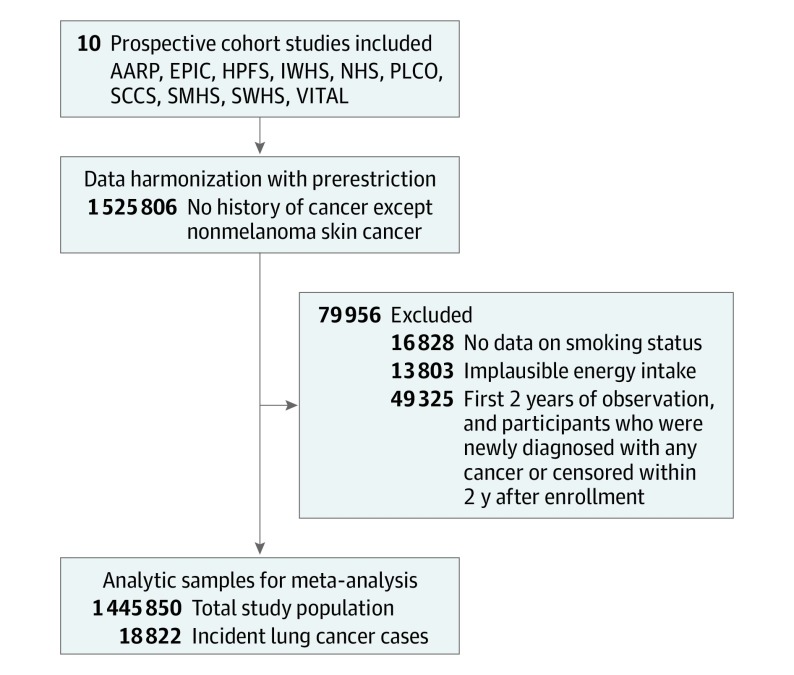

Of the initial study participants, we excluded individuals who had a history of any cancer, except nonmelanoma skin cancer, at cohort enrollment or no data on smoking history or implausible energy intake (beyond 3 standard deviations of the log-transformed cohort- and sex-specific mean). We further excluded the first 2 years of observation, and participants who developed any cancer or were censored within 2 years to minimize the potential reverse causation due to preclinical cancer-related dietary changes (Figure 1). The characteristics of our analytic sample of 1 445 850 participants are summarized in eTable 1 in the Supplement.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of Study Participant Selection and Exclusion.

AARP indicates National Health Institute-AARP Diet and Health Study; EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition; HPFS, Health Professionals Follow-up Study; IWHS, Iowa Women’s Health Study; NHS, Nurses’ Health Study; PLCO, Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial; SCCS, Southern Community Cohort Study; SMHS, Shanghai Men’s Health Study; SWHS, Shanghai Women’s Health Study, and VITAL, Vitamins and Lifestyle Study.

Diet and Outcome Assessment

At the baseline survey of each cohort, dietary information was collected using validated food frequency questionnaires or semiquantitative dietary questionnaires. Details of dietary assessment and validity have been described previously; the correlation coefficients between dietary questionnaires and dietary records/recalls ranged from 0.48 to 0.86 for dietary fiber.26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36 Few studies reported specific validation results for yogurt, but in the NHS and HPFS, yogurt assessment showed a high validity; the correlation coefficient with criterion was 0.74.29 Dietary fiber intake (grams per day) was calculated by multiplying the frequency of food consumption by portion size and fiber content, based on population-specific food composition tables or the enzymatic-gravimetric methods of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists,37 and categorized into sex-specific quintiles. Yogurt consumption (grams per day) was calculated by multiplying the frequency of consumption by study-specific portion size. The SMHS and SWHS had no data on yogurt consumption, which was uncommon when the cohort members were enrolled; thus, these 2 cohorts were excluded from any yogurt-related analyses. Considering that 20% to 76% of participants did not consume any yogurt (eTable 1 in the Supplement), we categorized yogurt consumption into 3 groups: a nonconsumption group (0 g/d) and 2 consumption groups (low or high: ≤ or > the sex-specific median intake, respectively). All dietary intakes were adjusted for total energy intake using the residual method.38

Incident cancer cases and deaths were identified via linkage to cancer and death registries, follow-up surveys, and review of medical records. The main study outcome was primary lung cancer (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revisions: codes 162 and C34, respectively), subclassified by tumor histologic type: adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, small cell carcinoma, or others. The time-to-event analysis was started 2 years from the date of enrollment and censored on the date of any cancer diagnosis, death, loss to follow-up, or the latest follow-up/linkage, whichever came first.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics across fiber and yogurt intakes were compared using the χ2 test or the general linear model. Spearman correlations of dietary fiber and yogurt intakes were assessed. We adopted a 2-stage individual participant data meta-analysis method.39 Using Cox proportional hazards models, we first estimated the cohort-specific hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs, using the lowest quintile for fiber and nonconsumption for yogurt as the reference; then all estimates were pooled using random-effects meta-analysis given the existence of between-study heterogeneity.40,41 In consideration of varying enrollment times and age ranges across participating cohorts, Cox models were stratified by birth year (5-year intervals from <1925 to ≥1960) and enrollment year (<1985, 1990, 1995, 2000, and ≥2005). Follow-up time was treated as the time scale. The global goodness-of-fit test with Schoenfeld residuals confirmed no violation against the proportional hazards assumption. Covariates included age, smoking status (never, former, or current), smoking pack-years (continuous), energy intake (continuous), sex, race/ethnicity (white, black, Asian, or other), educational level (<high school, high school graduate, vocational/professional, college, ≥university), obesity status (body mass index, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared: <18.5, 18.5-24.9, 25.0-29.9, or ≥30.0 for Westerners, and <18.5, 18.5-22.9, 23.0-27.4, or ≥27.5 for Asian persons), history of diabetes (yes or no), family history of lung cancer (yes or no), physical activity (tertiles of total physical active hours), menopause (yes or no), and intakes of saturated and polyunsaturated fat (sex-specific quintiles). Missing covariates were imputed in each cohort, separately (eAppendix in the Supplement). Linear trend was tested using a continuous variable with median values of each fiber or yogurt intake category. Potential nonlinear associations were evaluated using restricted cubic splines. Stratified analyses were conducted to assess the potential effect modification by sex, race/ethnicity, tumor histologic type, and other risk factors. Interaction was tested in each study by the likelihood-ratio test, entering a cross-product term of fiber or yogurt consumption and the stratification variables as both ordinal variables; then the estimates were pooled using random-effects meta-analysis.42 The joint association of fiber and yogurt with lung cancer risk was assessed in a pooled data analysis using the lowest intake of both fiber and yogurt as the reference.

A series of sensitivity analyses were conducted using (1) the common or the cohort- and sex-specific cutoffs; (2) fixed-effect meta-analysis or pooled individual participant data analysis; (3) the energy density method for total energy adjustment; and (4) further adjustment for red meat and vegetable intakes. To better evaluate potential confounding by smoking, we conducted a sequential adjustment for smoking intensity: (1) the minimal model, including age, energy intake, sex, and race/ethnicity; (2) the model adjusted for all covariates except smoking-related variables; (3) the model adjusted for all other covariates and smoking status; and (4) the final model (main results) that included all covariates, including smoking status and pack-years. Analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide, version 7.1 (SAS Institute Inc), or Stata, version 12 (StataCorp). Two-sided P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The analytic sample included 627 988 men, with a mean (SD) age of 57.9 (9.0) years, and 817 862 women, with a mean (SD) age of 54.8 (9.7) years (eTable 1 in the Supplement). During the median follow-up period of 8.6 years (after excluding the first 2 years), 18 822 cases of incident lung cancer were identified. The median (interquartile range) intake of dietary fiber was 18.4 (14.1-23.1) g/d. Overall, 62.2% of participants reported yogurt consumption, among whom the median (interquartile range) intake was 23.3 (5.7-73.4) g/d. Basic characteristics of lung cancer cases are summarized in eTable 2 in the Supplement.

Men with high fiber or yogurt intake had higher educational attainment, that is, university degree or above (lowest vs highest, 34.4% vs 45.5% for fiber; 40.0% vs 47.9% for yogurt), and healthy lifestyles, including less current smoking (39.1% vs 13.2% for fiber; 18.7% vs 16.0% for yogurt), less alcohol consumption (27.1 vs 10.3 g/d for fiber; 19.0 vs 14.9 g/d for yogurt), and more physical activity than those with low intakes (all P < .05) (Table 1). Among men, a history of diabetes was associated with high fiber intake (lowest vs highest, 5.8% vs 9.3%) but not with yogurt (9.0% vs 6.0%). Fiber and yogurt intakes were similarly associated with these characteristics in women (Table 1). For both men (r = 0.26) and women (r = 0.24), fiber and yogurt intakes were correlated (P < .001).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Study Population by Total Fiber Intake and Yogurt Consumptiona.

| Characteristic | Total Fiber Intakeb | Yogurt Consumptionc | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | None | Low | High | |

| Men (n = 627 988) | ||||||||

| Population, No. | 125 597 | 125 598 | 125 597 | 125 598 | 125 598 | 264 808 | 149 562 | 149 562 |

| Age, y | 57.4 | 58.6 | 58.2 | 57.7 | 57.6 | 59.8 | 58.7 | 55.1 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | ||||||||

| White | 56.5 | 86.4 | 92.5 | 93.7 | 93.5 | 92.1 | 92.1 | 97.5 |

| Black | 3.8 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 5.1 | 6.6 | 6.2 | 1.5 |

| Asiand | 39.7 | 8.9 | 2.7 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.0 |

| University degree or above, % | 34.4 | 42.2 | 44.2 | 44.0 | 45.5 | 40.0 | 45.5 | 47.9 |

| BMI | 25.9 | 27.0 | 27.1 | 27.0 | 26.6 | 27.2 | 27.3 | 26.6 |

| Diabetes, % | 5.8 | 7.4 | 7.9 | 8.4 | 9.3 | 9.0 | 8.2 | 6.0 |

| Family history of lung cancer, % | 3.2 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 1.3 |

| Smoking status, % | ||||||||

| Never | 24.1 | 27.2 | 29.6 | 32.0 | 36.1 | 25.6 | 29.3 | 37.2 |

| Former | 36.8 | 51.9 | 53.2 | 51.8 | 50.7 | 55.7 | 54.2 | 46.8 |

| Current | 39.1 | 20.9 | 17.2 | 16.2 | 13.2 | 18.7 | 16.5 | 16.0 |

| Ever smokers, pack-yearse | 34.4 | 33.9 | 31.2 | 28.8 | 26.9 | 35.5 | 31.5 | 25.2 |

| Alcohol intake, g/d | 27.1 | 18.7 | 15.5 | 13.4 | 10.3 | 19.0 | 18.0 | 14.9 |

| Low-level physical activity, %f | 44.1 | 27.4 | 23.5 | 21.8 | 19.2 | 25.5 | 20.9 | 21.2 |

| Dietary intakeg | ||||||||

| Energy, kcal/d | 2047 | 2122 | 2189 | 2239 | 2249 | 2164 | 2195 | 2261 |

| Total fiber, g/d | 10.7 | 15.6 | 19.2 | 23.1 | 31.0 | 19.2 | 21.3 | 23.3 |

| Yogurt, g/d | 7.7 | 14.5 | 21.4 | 29.1 | 35.4 | 0.0 | 4.5 | 82.5 |

| Saturated fat, g/d | 18.9 | 24.0 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 22.8 | 23.3 | 23.8 | 27.5 |

| Polyunsaturated fat, g/d | 11.6 | 14.7 | 15.1 | 15.1 | 14.9 | 15.1 | 15.2 | 14.3 |

| Women (n = 817 862) | ||||||||

| Population, No. | 163 572 | 163 572 | 163 573 | 163 572 | 163 573 | 230 174 | 257 125 | 257 139 |

| Age, y | 55.4 | 55.7 | 54.9 | 54.3 | 53.8 | 56.2 | 55.7 | 53.5 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | ||||||||

| White | 58.4 | 85.7 | 92.6 | 94.9 | 95.3 | 91.7 | 91.6 | 97.7 |

| Black | 6.0 | 6.3 | 5.1 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 7.6 | 7.4 | 2.0 |

| Asiand | 35.6 | 8.0 | 2.3 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.3 |

| University degree or above, % | 17.0 | 24.5 | 26.0 | 25.7 | 27.5 | 19.6 | 28.5 | 29.2 |

| BMI | 26.0 | 26.4 | 26.1 | 25.9 | 25.5 | 26.6 | 26.6 | 25.4 |

| Diabetes, % | 4.7 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 6.0 | 5.7 | 3.5 |

| Family history of lung cancer, % | 3.8 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 1.2 |

| Smoking status, % | ||||||||

| Never | 60.7 | 52.8 | 55.0 | 57.0 | 58.8 | 49.2 | 52.9 | 56.4 |

| Former | 19.7 | 28.2 | 28.0 | 27.8 | 28.8 | 27.4 | 30.4 | 29.1 |

| Current | 19.6 | 19.0 | 17.0 | 15.2 | 12.4 | 23.4 | 16.7 | 14.5 |

| Among ever smokers, pack-yearse | 27.9 | 22.6 | 19.3 | 17.0 | 15.5 | 24.0 | 20.8 | 16.3 |

| Alcohol intake, g/d | 7.7 | 6.7 | 6.3 | 5.7 | 4.7 | 6.5 | 7.2 | 6.6 |

| Low-level physical activity, %f | 45.1 | 30.6 | 28.0 | 26.4 | 23.2 | 28.7 | 28.3 | 25.2 |

| Menopause, % | 69.9 | 72.3 | 67.9 | 64.9 | 63.9 | 74.5 | 72.9 | 61.9 |

| Dietary intakeg | ||||||||

| Energy, kcal/d | 1673 | 1747 | 1818 | 1846 | 1829 | 1729 | 1830 | 1812 |

| Total fiber, g/d | 10.2 | 14.7 | 17.9 | 21.3 | 27.8 | 17.5 | 18.9 | 20.7 |

| Yogurt, g/d | 21.4 | 32.1 | 42.4 | 50.3 | 57.0 | 0.0 | 11.3 | 111.1 |

| Saturated fat, g/d | 16.8 | 21.2 | 22.8 | 23.0 | 21.1 | 21.5 | 20.9 | 24.1 |

| Polyunsaturated fat, g/d | 10.5 | 12.1 | 12.1 | 12.1 | 12.2 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 11.8 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); SMHS, Shanghai Men’s Health Study; SWHS, Shanghai Women’s Health Study; Q, quintile.

Baseline characteristics across quintiles of fiber intake and yogurt consumption groups were compared using the χ2 test for categorical variables or the general linear model for continuous variables. Data are mean values for continuous variables or proportions for categorical variables. Differences across quintiles or yogurt consumption groups for all listed variables are statistically significant (P < .05).

Based on the sex-specific quintiles.

Defined as none (0 g/d), low (≤sex-specific median intake), and high (>sex-specific median intake); participants from the SMHS and SWHS and those having invalid data on yogurt consumption were not included.

For fiber intake, included were Asian participants in the US and Chinese cohorts; for yogurt consumption, only Asian participants in the US cohorts were included. No data were available on yogurt consumption in the SMHS and SWHS.

Calculated among former and current smokers as (No. of cigarettes smoked per day × No. of years smoked)/20.

The lowest tertile of total physical activity measured by hours or metabolic equivalent hours.

Energy-adjusted mean intake per day using the residual method.

Both fiber and yogurt intakes were inversely associated with lung cancer risk (Table 2; and eFigure 1 and eFigure 2 in the Supplement). Individuals with the highest quintile of fiber intake showed a 17% lower risk (multivariable-adjusted HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.76-0.91; P < .001 for trend) than those with the lowest quintile. Compared with nonconsumers, low yogurt consumers had a 15% decreased risk for lung cancer (multivariable-adjusted HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.81-0.90), and high yogurt consumers had a 19% decreased risk for lung cancer (multivariable-adjusted HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.76-0.87) (both P < .001 for trend). The inverse associations were consistently observed in men and women and across histologic type. When stratified by race/ethnicity, we found significant inverse associations among white individuals, the largest racial/ethnic group of this study (for the highest vs lowest quintile of fiber: multivariable-adjusted HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.75-0.92; for high vs no yogurt consumption: multivariable-adjusted HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.77-0.88); whereas, black and Asian persons showed nonsignificant inverse associations, which were likely because of the much smaller sample sizes or lower intake levels (median [interquartile range] intakes of fiber and yogurt: 19.3 [15.4-23.7] and 25.8 [6.2-77.1] g/d for white persons; 17.8 [13.9-22.6] and 4.9 [1.7-19.0] g/d for black persons; and 10.8 [8.9-13.3] and 6.6 [1.9-29.6] g/d for Asian persons, respectively). Results from sequential adjustment models indicated that the primary associations with lung cancer attenuated after adjusting for smoking variables among black persons (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Spline analyses suggested a linear association for lung cancer and fiber intake but a nonlinear association for yogurt consumption (eFigure 3 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Risk of Lung Cancer by Dietary Fiber Intake and Yogurt Consumptiona,b.

| Variable | Total Fiber Intakec | Yogurt Consumptiond | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | P Value for Trend | None | Low | High | P Value for Trend | |

| Total study populations | ||||||||||

| Lung cancer cases, No. | 5686 | 4603 | 3440 | 2809 | 2284 | 9897 | 4326 | 2898 | ||

| HR (95% CI)e | 1 [Reference] | 0.96 (0.90-1.01) | 0.87 (0.81-0.94) | 0.85 (0.80-0.90) | 0.83 (0.76-0.91) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | 0.85 (0.81-0.90) | 0.81 (0.76-0.87) | <.001 |

| Men | ||||||||||

| Lung cancer cases, No. | 2687 | 2288 | 1898 | 1540 | 1288 | 5621 | 1897 | 1293 | ||

| HR (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 0.97 (0.88-1.07) | 0.94 (0.83-1.08) | 0.83 (0.74-0.94) | 0.84 (0.71-1.00) | .001 | 1 [Reference] | 0.83 (0.79-0.88) | 0.76 (0.71-0.82) | <.001 |

| Women | ||||||||||

| Lung cancer cases, No. | 2999 | 2315 | 1542 | 1269 | 996 | 4276 | 2429 | 1605 | ||

| HR (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 0.95 (0.88-1.03) | 0.83 (0.78-0.89) | 0.87 (0.80-0.94) | 0.84 (0.77-0.93) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | 0.89 (0.80-0.98) | 0.86 (0.78-0.95) | .002 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||

| White | ||||||||||

| Lung cancer cases, No. | 4193 | 4085 | 3148 | 2634 | 2114 | 9254 | 3973 | 2797 | ||

| HR (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 0.94 (0.88-0.99) | 0.85 (0.78-0.93) | 0.85 (0.79-0.91) | 0.83 (0.75-0.92) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | 0.85 (0.81-0.90) | 0.82 (0.77-0.88) | <.001 |

| Black | ||||||||||

| Lung cancer cases, No. | 194 | 191 | 183 | 123 | 116 | 484 | 253 | 65 | ||

| HR (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 0.99 (0.80-1.24) | 1.18 (0.94-1.48) | 0.90 (0.69-1.16) | 0.85 (0.65-1.12) | .26 | 1 [Reference] | 0.82 (0.69-0.96) | 0.83 (0.63-1.10) | .51 |

| Asian | ||||||||||

| Lung cancer cases, No. | 1243 | 291 | 73 | 28 | 21 | 60 | 37 | 14 | ||

| HR (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 1.10 (0.96-1.26) | 0.99 (0.77-1.29) | 0.70 (0.41-1.18) | 0.88 (0.47-1.65) | .99 | 1 [Reference] | 1.05 (0.63-1.75) | 0.73 (0.37-1.46) | .46 |

| Adenocarcinoma | ||||||||||

| Lung cancer cases, No. | 2035 | 1719 | 1293 | 1060 | 897 | 3446 | 1718 | 1149 | ||

| HR (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 0.99 (0.90-1.09) | 0.88 (0.81-0.96) | 0.86 (0.78-0.94) | 0.86 (0.75-0.99) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | 0.90 (0.84-0.96) | 0.85 (0.79-0.92) | .001 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | ||||||||||

| Lung cancer cases, No. | 972 | 814 | 589 | 478 | 374 | 1879 | 740 | 449 | ||

| HR (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 0.90 (0.81-0.99) | 0.79 (0.69-0.89) | 0.76 (0.67-0.86) | 0.74 (0.61-0.89) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | 0.84 (0.77-0.92) | 0.76 (0.67-0.86) | .007 |

| Small cell carcinoma | ||||||||||

| Lung cancer cases, No. | 763 | 636 | 453 | 372 | 273 | 1458 | 597 | 355 | ||

| HR (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 0.95 (0.85-1.06) | 0.86 (0.73-1.02) | 0.89 (0.77-1.03) | 0.90 (0.66-1.24) | .21 | 1 [Reference] | 0.87 (0.71-1.05) | 0.79 (0.68-0.92) | .001 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; Q, quintile.

Participants from the Shanghai Men’s and Women’s Health Studies were included in the fiber-lung cancer analysis only. No data were available on yogurt consumption in these 2 cohorts.

Estimated by random-effects meta-analysis.

Based on the sex-specific quintiles.

Defined as none (0 g/d), low (≤sex-specific median intake), and high (>sex-specific median intake).

All HRs were stratified by birth year and enrollment year and were adjusted for age, total energy, smoking status, smoking pack-years, sex, race/ethnicity, educational level, obesity status, diabetes, family history of lung cancer, physical activity level, menopausal status in women, and intakes of saturated and polyunsaturated fat.

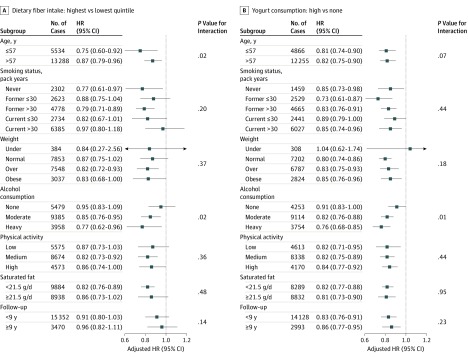

Age or alcohol consumption might modify the fiber or yogurt intake association with lung cancer (Figure 2). An inverse association of fiber was stronger in participants 57 years of age or younger (the median age of the study populations) than in those older than 57 years (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.60-0.92; vs HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.79-0.96; P = .02 for interaction). The association of fiber or yogurt with lung cancer was more evident among alcohol consumers than among nondrinkers, especially heavy alcohol consumers (for fiber: HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.62-0.96; P = .02 for interaction; for yogurt: HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.68-0.85; P = .01 for interaction).

Figure 2. Risk of Lung Cancer by Dietary Fiber Intake and Yogurt Consumption in Subgroups of Participants.

Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs were estimated by random-effects meta-analyses based on the sex-specific quintiles of total dietary fiber intake or yogurt consumption (none, 0 g/d; low, ≤sex-specific median intake; high, >sex-specific median intake). Participants from the Shanghai Men’s and Women’s Health Studies were included in the fiber-lung cancer analysis only. No data were available on yogurt consumption in these 2 cohorts. Age, saturated fat intake, and follow-up time were grouped by their median values. Heavy drinkers were defined as alcohol consumers who reported ethanol consumption of more than 28 g per day in men or more than 14 g per day in women; and moderate drinkers were defined as alcohol consumers who reported ethanol consumption of greater than 0 to 28 g per day in men or greater than 0 to 14 g per day in women. Physical activity levels were defined as tertiles of total physical active hours or metabolic equivalent hours. All models were stratified by birth year and enrollment year and adjusted for age, total energy, smoking status, smoking pack-years, sex, race/ethnicity, educational level, obesity status, diabetes, family history of lung cancer, physical activity level, menopausal status in women, and intakes of saturated and polyunsaturated fat.

We found a potential joint association of fiber and yogurt with lung cancer risk (Table 3). Individuals who reported high yogurt consumption with the highest quintile of fiber intake had a 33% reduced lung cancer risk (95% CI, 0.61-0.73) compared with those who did not consume yogurt and had the lowest quintile of fiber intake (P = .06 for interaction). When stratified by smoking status, HRs (95% CIs; P for interactions) were 0.74 (0.67-0.83; P = .04) among current, 0.66 (0.59-0.73; P = .45) among former, and 0.69 (0.54-0.89; P = .02) among never smokers for the highest fiber intake with yogurt consumption vs the lowest fiber intake without yogurt consumption. Similar results were found in all sensitivity analyses (eTable 4, eTable 5, and eTable 6 in the Supplement).

Table 3. Joint Association of Dietary Fiber Intake and Yogurt Consumption With Lung Cancer Riska,b.

| Yogurt Consumptionc | Total Fiber Intake | P Value for Interaction | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | |||||||

| Lung Cancer Cases, No. | HR (95% CI)d | Lung Cancer Cases, No. | HR (95% CI) | Lung Cancer Cases, No. | HR (95% CI) | Lung Cancer Cases, No. | HR (95% CI) | Lung Cancer Cases, No. | HR (95% CI) | ||

| Total populations | |||||||||||

| None | 3148 | 1 [Reference] | 2669 | 0.96 (0.91-1.01) | 1846 | 0.91 (0.86-0.97) | 1293 | 0.88 (0.82-0.94) | 941 | 0.86 (0.80-0.93) | .06 |

| Low | 926 | 0.87 (0.81-0.93) | 1040 | 0.80 (0.74-0.85) | 917 | 0.78 (0.73-0.85) | 773 | 0.74 (0.68-0.81) | 670 | 0.74 (0.68-0.81) | |

| High | 362 | 0.91 (0.82-1.02) | 592 | 0.82 (0.75-0.90) | 585 | 0.68 (0.62-0.75) | 715 | 0.76 (0.69-0.83) | 644 | 0.67 (0.61-0.73) | |

| Current smokers | |||||||||||

| None | 2047 | 1 [Reference] | 1415 | 0.95 (0.89-1.02) | 854 | 0.92 (0.85-1.00) | 524 | 0.90 (0.81-0.99) | 350 | 0.95 (0.84-1.07) | .04 |

| High or low | 773 | 0.94 (0.87-1.02) | 769 | 0.84 (0.77-0.92) | 643 | 0.77 (0.70-0.84) | 628 | 0.82 (0.74-0.91) | 465 | 0.74 (0.67-0.83) | |

| Former smokers | |||||||||||

| None | 974 | 1 [Reference] | 1080 | 0.96 (0.88-1.04) | 847 | 0.90 (0.82-0.98) | 647 | 0.86 (0.78-0.96) | 498 | 0.81 (0.73-0.91) | .45 |

| High or low | 443 | 0.83 (0.74-0.93) | 705 | 0.77 (0.70-0.85) | 679 | 0.70 (0.64-0.78) | 661 | 0.67 (0.60-0.74) | 660 | 0.66 (0.59-0.73) | |

| Never smokers | |||||||||||

| None | 127 | 1 [Reference] | 174 | 0.91 (0.72-1.15) | 145 | 0.81 (0.63-1.03) | 122 | 0.78 (0.60-1.01) | 93 | 0.67 (0.50-0.89) | .02 |

| High or low | 72 | 0.68 (0.51-0.91) | 158 | 0.76 (0.60-0.96) | 180 | 0.73 (0.58-0.93) | 199 | 0.77 (0.61-0.98) | 189 | 0.69 (0.54-0.89) | |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; Q, quintile.

Based on the sex-specific quintiles of total dietary fiber intake.

Defined as none (0 g/d), low (≤sex-specific median intake), and high (>sex-specific median intake); for stratified analyses, low and high yogurt consumption were combined into 1 group to increase the sample size of the strata and to improve the stability of risk estimates.

Participants from the Shanghai Men’s and Women’s Health Studies were included in the fiber-lung cancer analysis only. No data were available on yogurt consumption in these 2 cohorts.

All HRs were estimated in a single model stratified by cohort, birth year, and enrollment year and were adjusted for age, total energy, smoking status, smoking pack-years, sex, race/ethnicity, educational level, obesity status, diabetes, family history of lung cancer, physical activity level, menopausal status in women, and intakes of saturated and polyunsaturated fat.

Discussion

In this pooled analysis of more than 1.44 million individuals from 10 prospective cohorts, we found that high intakes of dietary fiber and yogurt were associated with a 15% to 19% reduced risk of lung cancer after controlling for a wide range of risk factors, including smoking status and pack-years, and putative dietary confounders, such as intakes of saturated and polyunsaturated fat.25 In addition, we found a potential synergistic association of fiber and yogurt with lung cancer risk: high intakes of both fiber and yogurt were associated with a 33% reduced risk of lung cancer. All the individual or joint associations were observed in the analyses stratified by smoking status. Our findings suggest that the health benefits of fiber and yogurt may include protection against lung cancer in addition to their well-established beneficial effects on cardiovascular disease and gastrointestinal cancer.6,7,8,10,11

A protective role of dietary fiber against COPD has been previously suggested. In the NHS and HPFS, 2 participating cohorts in our study, the highest quintile of fiber intake was associated with a 33% lower risk of COPD than the lowest quintile.17 Similarly, in a Swedish cohort, men who consumed dietary fiber of 36.8 g/d or more showed a 38% lower risk of COPD than those with an intake of less than 23.7 g/d.18 Lung cancer, particularly squamous cell carcinoma, and COPD share underlying molecular pathways.43 In addition, a high-fiber diet was linked to better lung function in a dose-response manner in US populations.16 Findings of our study are in line with these previous studies on COPD and lung function, but are not in line with the finding of the UK Million Women Study, which reported a null association between fiber intake and lung cancer risk among never smokers (823 cases included; HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.88-1.09 per 5 g/d increase).22 For yogurt, a recent meta-analysis, including 2 cohort studies and 3 case-control studies, reported a nonsignificant inverse association between yogurt and lung cancer risk (1294 cases included; relative risk, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.62-1.25 for high vs low yogurt consumption).23 In addition to its much smaller sample size, that meta-analysis was limited by heterogeneity in study design and different covariate adjustments. The large sample size and the availability of individual-level data in the present study overcame the limitations of the previous studies.

The health benefits of fiber and yogurt may be rooted in their prebiotic and probiotic properties, through which they independently or synergistically modulate gut microbiota.1,2,3 Dietary fiber is nondigestible by humans but can be fermentable by gut microbiota to generate short-chain fatty acids.44 Emerging evidence has suggested that the beneficial effects of short-chain fatty acids on host immune and metabolism are not restricted to the gut but reach various organs, including the lungs.14,44,45 Animal studies have shown that a high-fiber diet can remodel the immunological environment in the lungs by changing the composition of both gut and lung microbiota.45 Yogurt, a nutrient-dense food commonly containing strain-specific probiotics, can also enhance gut microbial communities. As an immunomodulator, furthermore, probiotics mediate cytokine secretion and proliferation and differentiation of immune cells.3 There are high expectations that yogurt may help prevent lung diseases; in vivo and in vitro studies have shown that some probiotic strains inhibit lung metastasis, enhance natural killer cell activity, and have antitumor and anti-inflammatory activities.46,47

In the present study, the inverse association of lung cancer risk with dietary fiber and yogurt consumption was more evident for squamous cell carcinoma and among participants with proinflammatory conditions (eg, heavy consumers of alcohol), suggesting that fiber and yogurt may exert beneficial effects on lung carcinogenesis via anti-inflammatory mechanisms. Previous studies have shown that a high-fiber diet and yogurt consumption were independently inversely associated with proinflammatory cytokines and inflammatory responses.7,48 Emerging evidence has also indicated a synergistic effect of prebiotics and probiotics on host health; fermentation of prebiotics can promote the colonization of health-promoting probiotic bacteria, such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, in the gastrointestinal tract,3 which can improve the gut microbial ecosystem, and in turn, increase the beneficial physiological effects of bacteria. Our present findings indicated that the combination of prebiotics (fiber) and probiotics (yogurt) may be stronger against lung cancer than either component alone. This finding suggests a potential role of increasing both prebiotic and probiotic consumption in lung cancer prevention.

Strengths and Limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest prospective study investigating the association of dietary fiber and yogurt consumption with lung cancer risk, and no previous epidemiologic study has investigated a joint association of fiber and yogurt with lung carcinogenesis. Over 1.44 million individual participant data, including diverse racial/ethnic groups and long-term observations, enabled us to comprehensively investigate the potential roles of dietary fiber, yogurt, and their joint activity in the development of lung cancer, with consideration of a wide range of potential confounders and effect modifiers. Detailed data on individuals’ smoking history, as well as tumor histology, allowed for in-depth analyses on the fiber or yogurt intake association with lung cancer. The first 2 years of follow-up were excluded from analyses to minimize potential reverse causation due to preclinical cancer-related dietary changes; although the data are not included in the supplemental information, the results remained robust even when the first 4 years of follow-up were excluded.

Nevertheless, we acknowledge several limitations. First, we had no data on types (eg, soluble vs insoluble) and food sources of fiber (eg, from grains, vegetables, or fruits); thus, we could not investigate the association by fiber subtypes. Data were also unavailable on types of yogurt (eg, sugar content and bacteria strains), which may differ across populations and confer different health effects. In addition, we could not evaluate possible changes in fiber and yogurt consumption over time because of data unavailability, which might result in attenuated associations.49 Second, despite the comprehensive adjustments for covariates, we cannot completely rule out the influence of residual confounding by smoking or unmeasured confounders, such as socioeconomic status and a history of COPD. Third, although we found similar results after adjusting for putative dietary risk factors, it is still possible that the observed associations were confounded by other dietary constituents associated with fiber and yogurt. Fourth, although the inverse association pattern was consistently observed across racial/ethnic groups, the associations for black or Asian persons failed to reach statistical significance in multivariable-adjusted models. Whereas those results are likely attributable to a lack of statistical power owing to small sample sizes or lower intake levels, a true racial/ethnic–specific association cannot be completely ruled out. Further investigation is needed to evaluate the association of fiber or yogurt consumption with lung cancer risk among those populations. Finally, measurement errors in dietary assessment may exist, which is likely to bias the estimates toward the null.50,51

Conclusions

In this large pooled analysis, after adjusting for a wide range of known or putative lung cancer risk factors, we found that dietary fiber and yogurt consumption were both associated with reduced risk of lung cancer. For the first time to our knowledge, a potential synergistic association between fiber and yogurt intakes on lung cancer risk was observed. Although further investigation is needed to replicate these findings and disentangle the underlying mechanisms, our study suggests a potential novel health benefit of increasing dietary fiber and yogurt intakes in lung cancer prevention.

eAppendix. Missing Data Imputation for Covariates

eTable 1. Characteristics of the Participating Cohort Studies

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics of Lung Cancer Cases

eTable 3. Hazard Ratios (95% CIs) of Lung Cancer by Dietary Fiber Intake and Yogurt Consumption in Sequential Adjustment Models

eTable 4. Hazard Ratios (95% CIs) of Lung Cancer by Dietary Fiber Intake and Yogurt Consumption: Using the Common Cut-Points of Fiber and Yogurt Intakes Across Cohorts

eTable 5. Hazard ratios (95% CIs) of Lung Cancer by Dietary Fiber Intake and Yogurt Consumption: Using the Cohort- and Sex-Specific Cut-Points of Fiber and Yogurt Intakes

eTable 6. Hazard ratios (95% CIs) of Lung Cancer by Dietary Fiber Intake and Yogurt Consumption: Sensitivity Analyses Among the Total Study Population

eFigure 1. Lung Cancer Risk Associated With Dietary Fiber Intake in Each Participating Cohort

eFigure 2. Lung Cancer Risk Associated With Yogurt Consumption in Each Participating Cohort

eFigure 3. Dose-Response Relationship of Dietary Fiber Intake and Yogurt Consumption With Lung Cancer Risk

References

- 1.Sonnenburg JL, Bäckhed F. Diet-microbiota interactions as moderators of human metabolism. Nature. 2016;535(7610):-. doi: 10.1038/nature18846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aron-Wisnewsky J, Clément K. The gut microbiome, diet, and links to cardiometabolic and chronic disorders. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12(3):169-181. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2015.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hemarajata P, Versalovic J. Effects of probiotics on gut microbiota: mechanisms of intestinal immunomodulation and neuromodulation. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2013;6(1):39-51. doi: 10.1177/1756283X12459294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bindels LB, Delzenne NM, Cani PD, Walter J. Towards a more comprehensive concept for prebiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(5):303-310. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; World Health Organization . Probiotics in Food: Health and Nutritional Properties and Guidelines for Evaluation. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United States; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson JW, Baird P, Davis RH Jr, et al. Health benefits of dietary fiber. Nutr Rev. 2009;67(4):188-205. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00189.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun J, Buys N. Effects of probiotics consumption on lowering lipids and CVD risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Med. 2015;47(6):430-440. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2015.1071872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dehghan M, Mente A, Rangarajan S, et al. ; Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study investigators . Association of dairy intake with cardiovascular disease and mortality in 21 countries from five continents (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2018;392(10161):2288-2297. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31812-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho SS, Qi L, Fahey GC Jr, Klurfeld DM. Consumption of cereal fiber, mixtures of whole grains and bran, and whole grains and risk reduction in type 2 diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(2):594-619. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.067629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aune D, Chan DSM, Lau R, et al. Dietary fibre, whole grains, and risk of colorectal cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ. 2011;343:d6617. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pala V, Sieri S, Berrino F, et al. Yogurt consumption and risk of colorectal cancer in the Italian European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition cohort. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(11):2712-2719. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Z, Xu G, Ma M, Yang J, Liu X. Dietary fiber intake reduces risk for gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):113-120. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park Y, Subar AF, Hollenbeck A, Schatzkin A. Dietary fiber intake and mortality in the NIH-AARP diet and health study. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(12):1061-1068. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McAleer JP, Kolls JK. Contributions of the intestinal microbiome in lung immunity. Eur J Immunol. 2018;48(1):39-49. doi: 10.1002/eji.201646721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butler LM, Koh W-P, Lee H-P, Yu MC, London SJ. Dietary fiber and reduced cough with phlegm: a cohort study in Singapore. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(3):279-287. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200306-789OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kan H, Stevens J, Heiss G, Rose KM, London SJ. Dietary fiber, lung function, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(5):570-578. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varraso R, Willett WC, Camargo CA Jr. Prospective study of dietary fiber and risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among US women and men. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(7):776-784. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaluza J, Harris H, Wallin A, Linden A, Wolk A. Dietary fiber intake and risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective cohort study of men. Epidemiology. 2018;29(2):254-260. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gnagnarella P, Maisonneuve P, Bellomi M, et al. Nutrient intake and nutrient patterns and risk of lung cancer among heavy smokers: results from the COSMOS screening study with annual low-dose CT. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013;28(6):503-511. doi: 10.1007/s10654-013-9803-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kane-Diallo A, Srour B, Sellem L, et al. Association between a pro plant-based dietary score and cancer risk in the prospective NutriNet-santé cohort. Int J Cancer. 2018;143(9):2168-2176. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vieira AR, Abar L, Vingeliene S, et al. Fruits, vegetables and lung cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(1):81-96. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pirie K, Peto R, Green J, Reeves GK, Beral V; Million Women Study Collaborators . Lung cancer in never smokers in the UK Million Women Study. Int J Cancer. 2016;139(2):347-354. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Y, Wang X, Yao Q, Qin L, Xu C. Dairy product, calcium intake and lung cancer risk: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20624. doi: 10.1038/srep20624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu D, Takata Y, Smith-Warner SA, et al. Prediagnostic calcium intake and lung cancer survival: a pooled analysis of 12 cohort studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(7):1060-1070. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang JJ, Yu D, Takata Y, et al. Dietary fat intake and lung cancer risk: a pooled analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(26):3055-3064. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.3329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson FE, Kipnis V, Midthune D, et al. Performance of a food-frequency questionnaire in the US NIH-AARP (National Institutes of Health-American Association of Retired Persons) Diet and Health Study. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(2):183-195. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of an expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135(10):1114-1126. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willett WC, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122(1):51-65. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salvini S, Hunter DJ, Sampson L, et al. Food-based validation of a dietary questionnaire: the effects of week-to-week variation in food consumption. Int J Epidemiol. 1989;18(4):858-867. doi: 10.1093/ije/18.4.858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munger RG, Folsom AR, Kushi LH, Kaye SA, Sellers TA. Dietary assessment of older Iowa women with a food frequency questionnaire: nutrient intake, reproducibility, and comparison with 24-hour dietary recall interviews. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136(2):192-200. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Subar AF, Thompson FE, Kipnis V, et al. Comparative validation of the Block, Willett, and National Cancer Institute food frequency questionnaires: the Eating at America’s Table Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(12):1089-1099. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.12.1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Signorello LB, Munro HM, Buchowski MS, et al. Estimating nutrient intake from a food frequency questionnaire: incorporating the elements of race and geographic region. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(1):104-111. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White E, Patterson RE, Kristal AR, et al. VITamins And Lifestyle cohort study: study design and characteristics of supplement users. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(1):83-93. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slimani N, Ferrari P, Ocké M, et al. Standardization of the 24-hour diet recall calibration method used in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC): general concepts and preliminary results. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000;54(12):900-917. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Villegas R, Yang G, Liu D, et al. Validity and reproducibility of the food-frequency questionnaire used in the Shanghai men’s health study. Br J Nutr. 2007;97(5):993-1000. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507669189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shu XO, Yang G, Jin F, et al. Validity and reproducibility of the food frequency questionnaire used in the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58(1):17-23. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prosky L, Asp NG, Furda I, DeVries JW, Schweizer TF, Harland BF. Determination of total dietary fiber in foods and food products: collaborative study. J Assoc Off Anal Chem. 1985;68(4):677-679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Willett WC, Howe GR, Kushi LH. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65(4)(suppl):1220S-1228S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.4.1220S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burke DL, Ensor J, Riley RD. Meta-analysis using individual participant data: one-stage and two-stage approaches, and why they may differ. Stat Med. 2017;36(5):855-875. doi: 10.1002/sim.7141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177-188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith-Warner SA, Spiegelman D, Ritz J, et al. Methods for pooling results of epidemiologic studies: the Pooling Project of Prospective Studies of Diet and Cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(11):1053-1064. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hua H, Burke DL, Crowther MJ, Ensor J, Tudur Smith C, Riley RD. One-stage individual participant data meta-analysis models: estimation of treatment-covariate interactions must avoid ecological bias by separating out within-trial and across-trial information. Stat Med. 2017;36(5):772-789. doi: 10.1002/sim.7171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bozinovski S, Vlahos R, Anthony D, et al. COPD and squamous cell lung cancer: aberrant inflammation and immunity is the common link. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173(4):635-648. doi: 10.1111/bph.13198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koh A, De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Bäckhed F. From dietary fiber to host physiology: short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell. 2016;165(6):1332-1345. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trompette A, Gollwitzer ES, Yadava K, et al. Gut microbiota metabolism of dietary fiber influences allergic airway disease and hematopoiesis. Nat Med. 2014;20(2):159-166. doi: 10.1038/nm.3444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma A, Viswanath B, Park Y-S. Role of probiotics in the management of lung cancer and related diseases: an update. J Funct Foods. 2018;40:625-633. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2017.11.050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dasari S, Kathera C, Janardhan A, Praveen Kumar A, Viswanath B. Surfacing role of probiotics in cancer prophylaxis and therapy: a systematic review. Clin Nutr. 2017;36(6):1465-1472. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chuang S-C, Vermeulen R, Sharabiani MTA, et al. The intake of grain fibers modulates cytokine levels in blood. Biomarkers. 2011;16(6):504-510. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2011.599042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu FB, Satija A, Rimm EB, et al. Diet assessment methods in the Nurses’ Health Studies and contribution to evidence-based nutritional policies and guidelines. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(9):1567-1572. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paeratakul S, Popkin BM, Kohlmeier L, Hertz-Picciotto I, Guo X, Edwards LJ. Measurement error in dietary data: implications for the epidemiologic study of the diet-disease relationship. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1998;52(10):722-727. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Willett W. Nutritional Epidemiology. 3rd ed Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Missing Data Imputation for Covariates

eTable 1. Characteristics of the Participating Cohort Studies

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics of Lung Cancer Cases

eTable 3. Hazard Ratios (95% CIs) of Lung Cancer by Dietary Fiber Intake and Yogurt Consumption in Sequential Adjustment Models

eTable 4. Hazard Ratios (95% CIs) of Lung Cancer by Dietary Fiber Intake and Yogurt Consumption: Using the Common Cut-Points of Fiber and Yogurt Intakes Across Cohorts

eTable 5. Hazard ratios (95% CIs) of Lung Cancer by Dietary Fiber Intake and Yogurt Consumption: Using the Cohort- and Sex-Specific Cut-Points of Fiber and Yogurt Intakes

eTable 6. Hazard ratios (95% CIs) of Lung Cancer by Dietary Fiber Intake and Yogurt Consumption: Sensitivity Analyses Among the Total Study Population

eFigure 1. Lung Cancer Risk Associated With Dietary Fiber Intake in Each Participating Cohort

eFigure 2. Lung Cancer Risk Associated With Yogurt Consumption in Each Participating Cohort

eFigure 3. Dose-Response Relationship of Dietary Fiber Intake and Yogurt Consumption With Lung Cancer Risk