Abstract

Background/Objectives:

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the common gastrointestinal disorders worldwide. Recent epidemiologic studies have suggested that use of statins may lower the risk of GERD although the results from different studies were inconsistent. This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted with the aim to summarize all available data.

Methods:

A systematic literature review was performed using MEDLINE and EMBASE database from inception to December 2017. Cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies that compared the risk of GERD among statin users versus nonusers were included. Pooled odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated using a random-effect, generic inverse variance method.

Results:

A total of 4 studies (1 case control, 1 cohort, and 2 cross-sectional studies) with 14,505 participants met the eligibility criteria and were included in the meta-analysis. The risk of GERD among statin users was numerically lower than nonusers with the pooled OR of 0.89 but the result did not achieve statistical significance (95% CI, 0.60–1.33). The statistical heterogeneity in this study was moderate (I2 = 54%).

Conclusions:

The current meta-analysis found that the risk of GERD was numerically lower among statin users although the pooled result did not reach statistical significance. Therefore, more studies are still needed to further clarify this potential benefit of statins.

KEY WORDS: Gastroesophageal reflux disease, hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitors, meta-analysis, reflux esophagitis, statins

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the common gastrointestinal problems around the world. The reported prevalence of GERD is approximately 10–20% in Western countries and less than 5% in Asia.[1] Heartburn and regurgitation are its classic manifestations although extra-esophageal manifestations such as asthma, chronic laryngitis, and sinusitis are also frequently seen.[2,3,4] Known risk factors of GERD include obesity, hiatal hernia, use of certain medications such as calcium channel blocker, anticholinergic, and tricyclic antidepressant.[5,6,7] Untreated GERD can lead to several long-term complications including esophageal stricture, Barrett's esophagitis, and esophageal cancer.[8,9,10]

Statins or hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitors are one of the most commonly used medications worldwide as a result of the global epidemic of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular diseases.[11] Previous studies suggested that the benefit of statins goes beyond the conventional cholesterol-lowering effect as they also have anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory property.[12,13,14] Interestingly, studies have suggested that use of statins is associated with a lower risk of Barrett's esophagus and esophageal cancer.[15,16,17] Since GERD is one of the important risk factors for esophageal cancer, the observations raise an interesting question whether the reduced risk of esophageal cancer by statins run through the protective effect against GERD. In fact, the decreased risk of GERD among statin users is observed by some epidemiologic studies although the results were inconclusive.[18,19,20] These systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted with the aim to summarize all available evidence to assess the risk of GERD among statin users versus nonusers.

Methods

Search strategy

Two investigators (K. W. and P. U.) independently searched for published studies indexed in the MEDLINE and EMBASE database from inception to December 2017 using the search strategy that included the terms “gastroesophageal reflux disease,” “reflux esophagitis,” “Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA Reductase Inhibitors,” and “Statins” as described in Online Supplementary Data 1 (11.1MB, tif) . A manual search for additional studies using references of selected retrieved articles was also performed. No language limitation was applied in this study. This study was conducted in accordance to the PRISMA (Preferred reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) statement which is provided as Online Supplementary Data 2 (10.4MB, tif) . EndNote X7 (Clarivate Analytics, Pennsylvania, United States) was used for study retrieval.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) case-control, cross-sectional, or cohort studies that compared the risk of GERD among subjects who use statins compared with subjects who do not use statins, (2) odds ratios (ORs), relative risks (RR), hazard ratios (HR), or standardized incidence ratios (SIR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) or sufficient raw data to calculate these ratios were provided.

Study eligibility was independently determined by three investigators (K. W., P. P., and P. U.). Differences in the determination of study eligibility were resolved by mutual consensus. The quality of each study was also independently evaluated by each investigator using the validated Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale.[21] This scale evaluated each study in three domains including the selection of the participants, the comparability between the groups as well as the ascertainment of the exposure of interest for case-control study, and the outcome of interest for cohort study. The modified Newcastle–Ottawa scale as described by Herzog et al. was used for cross-sectional study.[22] Kappa statistics were used for evaluation of inter-rater agreement on Newcastle–Ottawa scale.

Data extraction

A standardized data collection form was used to extract the following data from each study: title of the study, name of the first author, year(s) when the study was conducted, year when the study was published, country where the study was conducted, number of subjects, demographic data of subjects, methods used to diagnose GERD, methods used to verify statins use, adjusted effect estimates with 95% CIs, and covariates that were adjusted in the multivariate analysis.

To ensure the accuracy of data extraction, this process was independently conducted by three investigators (K. W., P. P., and P. U.). Case record forms were crosschecked and any data discrepancy was also resolved by referring back to the original articles.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.3 software from the Cochrane Collaboration (London, United Kingdom). Adjusted point estimates from each study were combined using the generic inverse variance method of DerSimonian and Laird which assigned the weight of each study in reverse to its variance.[23] As the outcome of interest was relatively uncommon, we used RR of cohort study as an estimate for OR to combine with OR from case-control study and cross-sectional study. In light of the possible high between-study variance due to different study designs and populations, we used a random-effect model rather than a fixed-effect model. Cochran's Q test and I2 statistic were used to determine the between-study heterogeneity. This I2 statistic quantifies the proportion of total variation across studies, that is, due to heterogeneity rather than chance. A value of I2 of 0–25% represents insignificant heterogeneity, greater than 25% but less than or equal to 50% represents low heterogeneity, greater than 50% but less than or equal to 75% represents moderate heterogeneity, and greater than 75% represents high heterogeneity.[24] We plan to use funnel plot to assess for the presence of publication bias.

Results

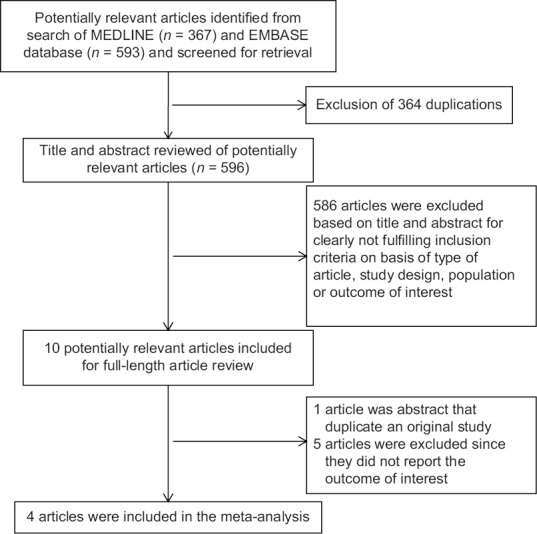

Our search strategy yielded 960 potentially relevant articles (367 articles from MEDLINE and 593 articles from EMBASE). After the exclusion of 364 duplicated articles, 596 of them underwent title and abstract review. Five hundred and eighty-six articles were excluded at this stage since they were case reports, letters to editor, review articles, basic science studies, animal studies, or interventional studies, leaving 10 articles for full-length article review. Five of them were excluded since they did not report the outcome of interest whereas 1 article[25] was excluded because it was a conference abstract that duplicated an original study.[20] Finally, 4 studies (2 cross-sectional studies,[6,19] 1 case-control study,[18] and 1 cohort study[20]) with 14,505 participants were included in the data analysis. The literature review and study selection process are demonstrated in Figure 1. The clinical characteristics and the quality assessment of the included studies are described in Table 1. PRISMA is provided as Online Supplementary Data 2 (10.4MB, tif) . It should be noted that the inter-rater agreement for the quality assessment using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale was high with the kappa statistics of 0.75.

Figure 1.

Literature review process

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the studies included in this meta-analysis

| Fujii et al.[18] | Nakaji et al.[19] | Asaoka et al.[6] | Smith et al.[20] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Japan | Japan | Japan | USA |

| Study design | Case-control study | Cross-sectional study | Cross-sectional study | Retrospective cohort study |

| Year of publication | 2009 | 2011 | 2016 | 2017 |

| Number of subjects | 438 (146 cases with GERD and 292 controls without GERD) | 201 (17 patients with GERD and 184 patients without GERD) | 1182 (127 patients with GERD and 1055 patients without GERD) | 12,684 (6342 statin-users and 6342 nonusers) |

| Baseline characteristics of participants | Male: 58.2% Mean age: 66.7±12.3 years |

Male: 47% Mean age: 70.5±12.7 years |

Male: 64.6% Mena age: 58.9±13.3 years Mean BMI: 24.6±3.9 kg/m2 |

Male: 53.9% Mean age: 55.7±12.4 years Overweight/Obesity: 15.1% Smoking: 8.0% |

| Comorbidity | N/A | Atrial fibrillation: 52.9% Coronary artery disease: 29.4% Stroke: 11.8% Diabetes mellitus and heart failure: 0.0% Hypertension: 29.4% |

Barrett’s mucosa: 38.6% Hiatal hernia: 75.6% |

Coronary atherosclerosis: 5.0% Cerebrovascular disease: 2.0% Diabetes mellitus: 12.4% Diabetes mellitus with complications: 3.9% Acute myocardial infarction: 0.4% Hypertension: 2.9% Asthma: 5.8% |

| Concurrent medication | Antiplatelet agents: 26% Aspirin: 22.6% Warfarin: 6.8% PPI: 11.0% |

Warfarin: 64.7% Antiplatelet agents: 35.3% ARB, ACEI: 35.3% CCB: 70.6% Antiarrhythmic drugs: 35.3% Beta-blockers: 41.2% Gastric medicine: 64.7% |

PPI: 24.4% H2RA: 10.2% CCB: 26.8% Bisphosphonates: 3.1% |

NSAIDs: 58.4% PPI: 32% Aspirin: 29.8% Beta-blocker: 17.7% SSRI: 16.8% CCB: 15.8% Nonstatin lipid-lowering drug: 6.2% |

| Recruitment of subjects | Cases: Cases were those who underwent upper endoscopy at Gunma Prefectural Cardiovascular Center (Japan) from December 2005 to October 2007 and was found to have GERD Controls: Controls were those who underwent upper endoscopy at the same medical center but were not found to have GERD |

Subjects were recruited from cardiology outpatient clinics in Kyushu, Japan between January 2008 and February 2010 | Subjects were those who underwent upper endoscopy at Jutendo University Hospital, Japan between February 2008 and November 2014 | Cohorts of statin users and nonusers were identified from a regional Military Healthcare System database from October 1, 2003 to March 1, 2012 |

| Definition of statin use | Use of pravastatin, rosuvastatin, atorvastatin, simvastatin, or pitivastatin within 7 days prior to the endoscopy | Current use of statins on the date of the survey | Use of statin for at least 6 months until the date of upper endoscopy | Presence of prescription (s) for statins in medical records before the index date |

| Diagnosis of GERD | Presence of reflux esophagitis on upper endoscopy | GERD was diagnosed using the Frequency Scale for Symptoms of GERD questionnaire (cutoff value of 8) | Presence of reflux esophagitis on upper endoscopy | Presence of diagnostic codes for GERD in the database |

| Confounder adjusted in multivariate analysis | Use of aspirin, H2 blockers, proton pump inhibitors and hiatal hernia | None | Sex, BMI, H. pylori infection, medications (CCB), and upper GI findings (Barrett’s mucosa, hiatal hernia, EGA) | Age, sex, and comorbidities |

| Quality assessment (Newcastle-Ottawa scale) | Selection: 2 | Selection: 2 | Selection: 3 | Selection: 3 |

| Comparability: 2 | Comparability: 2 | Comparability: 2 | Comparability: 2 | |

| Outcome: 3 | Outcome: 2 | Outcome: 3 | Outcome: 2 |

GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease, GI: Gastrointestinal, BMI: Body mass index, H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori, EGA: Endoscopic gastric mucosal atrophy, PPI: Proton pump inhibitors, H2RA: Histamine-2-receptor antagonists, ACEI: Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, ARB: Angiotensin II receptor blockers, NSAIDs: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, SSRI: Selective serotonin receptor inhibitor, N/A: Not available, CCB: Calcium channel blockers

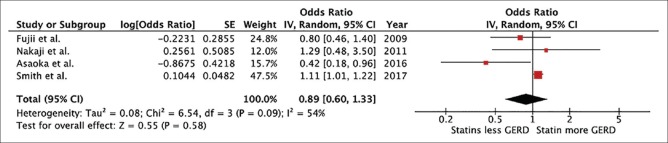

In this meta-analysis, the risk of GERD among statin users was numerically lower than nonusers with the pooled OR of 0.89 but the result did not achieve statistical significance (95% CI, 0.60–1.33). The heterogeneity in this study was moderate (I2 = 54%). The forest plot of this study is shown in Figure 2. Funnel plot was not used to assess for the presence of publication bias due to the small number of included studies.

Figure 2.

Forest plot

Discussion

To date, there is no systematic review of the effects of statins on GERD available in the Cochrane database and the current study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the protective effect of statins against development of GERD. We found that the risk of GERD was numerically lower among statin users compared with nonusers although the pooled result did not reach statistical significance which could be due to the lack of power as a result of small number of included studies and participants.

There are few theoretical explanations as to why use of statins may decrease the risk of GERD. Nitric oxide plays an important role in the regulation of the lower esophageal sphincter tone.[26,27] Increased nitric oxide level induces relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter which could predispose patients to GERD. A study in rat has demonstrated that statins can decrease nitric oxide production which may help increasing the lower esophageal sphincter tone.[28] Oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines are important players in the pathogenesis of GERD.[29,30,31] Therefore, use of statins could possibly decrease the risk of GERD through their anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory effect. However, epidemiologic studies on the association between use of statins and risk of GERD have yielded conflicting results, ranging from a significantly higher risk of GERD among statin users to a significantly higher risk of GERD among nonusers. The current study was conducted with the aim to take the advantage of systematic review and meta-analysis technique to summarize data from all studies. However, we still do not have enough power to demonstrate that the risk of GERD is significantly lower among statin users. In addition, the current study has some limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, all of the included studies were observational in nature and all but one study were either cross-sectional or case-control studies which were of less reliability compared with cohort studies to address the exposure-outcome dynamics. Second, adjustment for potential confounder in each study was not extensive (one study was unadjusted), and thus, influence of those factors on the outcome of interest could not be excluded. Moreover, the between-studies heterogeneity of this meta-analysis was not low. Therefore, the current systematic review and meta-analysis can only serve as preliminary data and further studies with a more vigorous study design are still needed to clarify this potential benefit of statins.

Conclusion

In summary, no statistically significant impact of statins on GERD was observed in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Online Supplementary Data

Search strategy

PRISMA checklist

References

- 1.Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: A systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.051821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DiBaise JK, Huerter JV, Quigley EM. Sinusitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:1078. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-12-199812150-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harding SM, Richter JE, Guzzo MR, Schan CA, Alexander RW, Bradley LA, et al. Asthma and gastroesophageal reflux: Acid suppressive therapy improves asthma outcome. Am J Med. 1996;100:395–405. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(97)89514-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Remacle M, Lawson G. Diagnosis and management of laryngopharyngeal reflux disease. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;14:143–9. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000193189.17225.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akyüz F, Mutluay Soyer Ö. Which diseases are risk factors for developing gastroesophageal reflux disease? Turk J Gastroenterol. 2017;28:S44–7. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2017.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asaoka D, Nagahara A, Hojo M, Matsumoto K, Ueyama H, Matsumoto K, et al. Association of medications for lifestyle-related diseases with reflux esophagitis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2016;12:1507–15. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S114709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corley DA, Kubo A, Zhao W. Abdominal obesity, ethnicity and gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms. Gut. 2007;56:756–62. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.109413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ronkainen J, Aro P, Storskrubb T, Johansson SE, Lind T, Bolling-Sternevald E, et al. High prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and esophagitis with or without symptoms in the general adult Swedish population: A Kalixanda study report. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:275–85. doi: 10.1080/00365520510011579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stasyshyn A. Diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease complicated by Barrett's esophagus. Pol Przegl Chir. 2017;89:29–32. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.3908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wesdorp IC, Bartelsman JF, den Hartog Jager FC, Huibregtse K, Tytgat GN. Results of conservative treatment of benign esophageal strictures: A follow-up study in 100 patients. Gastroenterology. 1982;82:487–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abud-Mendoza C, de la Fuente H, Cuevas-Orta E, Baranda L, Cruz-Rizo J, González-Amaro R, et al. Therapy with statins in patients with refractory rheumatic diseases: A preliminary study. Lupus. 2003;12:607–11. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu429oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferri N, Corsini A, Bellosta S. Pharmacology of the new P2Y12 receptor inhibitors: Insights on pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties. Drugs. 2013;73:1681–709. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0126-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain MK, Ridker PM. Anti-inflammatory effects of statins: Clinical evidence and basic mechanisms. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:977–87. doi: 10.1038/nrd1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwak B, Mulhaupt F, Myit S, Mach F. Statins as a newly recognized type of immunomodulator. Nat Med. 2000;6:1399–402. doi: 10.1038/82219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beales IL, Dearman L, Vardi I, Loke Y. Reduced risk of Barrett's esophagus in statin users: Case-control study and meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:238–46. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3869-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen T, Duan Z, Naik AD, Kramer JR, El-Serag HB. Statin use reduces risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in US veterans with Barrett's esophagus: A nested case-control study. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1392–8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh S, Singh AG, Singh PP, Murad MH, Iyer PG. Statins are associated with reduced risk of esophageal cancer, particularly in patients with Barrett's esophagus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:620–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujii T, Nakabayashi T, Hashimoto S, Kuwano H. Statin use and risk of gastroduodenal ulcer and reflux esophagitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:641–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakaji G, Fujihara M, Fukata M, Yasuda S, Odashiro K, Maruyama T, et al. Influence of common cardiac drugs on gastroesophageal reflux disease: Multicenter questionnaire survey. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;49:555–62. doi: 10.5414/cp201558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith I, Schmidt R, Halm EA, Mansi IA. Do statins increase the risk of esophageal conditions. Findings from four propensity score-matched analyses? Clin Drug Investig. 2018;38:135–46. doi: 10.1007/s40261-017-0589-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–5. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herzog R, Álvarez-Pasquin MJ, Díaz C, Del Barrio JL, Estrada JM, Gil Á, et al. Are healthcare workers' intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith IB, Mansi I. Are statins associated with upper gastrointestinal symptoms? Gastroenterology. 2017;152(5 Suppl 1):S305. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomita R, Tanjoh K, Fujisaki S, Fukuzawa M. Physiological studies on nitric oxide in the lower esophageal sphincter of patients with reflux esophagitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:110–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamato S, Saha JK, Goyal RK. Role of nitric oxide in lower esophageal sphincter relaxation to swallowing. Life Sci. 1992;50:1263–72. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90326-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giusti-Paiva A, Martinez MR, Felix JV, da Rocha MJ, Carnio EC, Elias LL, et al. Simvastatin decreases nitric oxide overproduction and reverts the impaired vascular responsiveness induced by endotoxic shock in rats. Shock. 2004;21:271–5. doi: 10.1097/10.shk.0000115756.74059.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kato M, Watabe K, Hamasaki T, Umeda M, Furubayashi A, Kinoshita K, et al. Association of low serum adiponectin levels with erosive esophagitis in men: An analysis of 2405 subjects undergoing physical check-ups. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1361–7. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0453-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tseng PH, Yang WS, Liou JM, Lee YC, Wang HP, Lin JT, et al. Associations of circulating gut hormone and adipocytokine levels with the spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux disease. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamoto K, Kiyohara T, Murayama Y, Kihara S, Okamoto Y, Funahashi T, et al. Production of adiponectin, an anti-inflammatory protein, in mesenteric adipose tissue in Crohn's disease. Gut. 2005;54:789–96. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.046516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Search strategy

PRISMA checklist