Abstract

Home care aides (HCAs) provide housekeeping and personal care services to help older clients remain in the community. However, little is known about the health of HCAs, who themselves constitute an underserved population. The goal of this study was to investigate how HCAs’ work and life contexts manifest themselves in HCAs’ health as perceived by HCAs. Six focus groups were conducted with HCAs (N=45). Analysis revealed how HCAs’ work-and life-related stress accumulated over time and affected HCAs’ health and interaction with their older clients. Home care aides were interested in personal health promotion and client well-being. Home care aides may constitute an underused resource for the care of older adults with disabilities. Information about intricately intertwined work and life contexts should inform policymakers and home care providers in their efforts to improve the quality of publicly funded home care services.

Keywords: Long-term care, home care services, caregivers, home care aides, occupational stress, life stress, health promotion, focus groups, vulnerable populations, underserved populations, Medicaid, frail elderly, aging, job task enrichment

Older adults who have difficulties with daily activities such as walking and bathing receive help mostly from their families.1 However, an increasing number of older adults receive help from paid caregivers.2,3 This is especially true for frail, low-income older adults who are eligible for publicly-funded long-term care programs, since federal and state governments are seeking alternatives to costly nursing home services by providing home and community-based services.4, 5 Home care aides (HCAs), also called personal care assistants and home makers, are non-medical paid caregivers who provide in-home services such as routine housekeeping (e.g., laundry, grocery shopping, preparing meals) and personal care services (e.g., bathing, dressing, transferring) to help older adults stay in the community and avoid nursing home placement. Home care aides work in a home care sector that involves complex arrays of public and private funds, most notably Medicaid, a public health insurance program for certain groups of low-income children and adults that is jointly managed by the state and federal governments and covers approximately 20% of Americans aged 65 and older.6

Despite HCAs’ critical roles in health care for older adults with disabilities, little is known about the health of HCAs, who themselves constitute an underserved population in the United States. Due to state-to-state variation in home care regulations and delivery systems and complex funding mechanisms, administrative data on home care providers and HCAs are not readily available for research. Home care aides are typically middle-aged women, often African American or other ethnic minorities or immigrants with high school-level education.7–9 However, these census-based data do not provide information on HCAs’ health. A small but growing literature indicates that HCAs face challenging working conditions such as job demands, lack of respect and isolation, and hazardous exposures ranging from slips, trips, and falls to sharps injuries and blood/body fluid exposure.10–15

Caregiving is a stressful occupation. The stress process perspective has been applied to the study of family or informal caregiving16 and occupational health and safety,17 but seldom to HCAs. Little is known about what kind and amount of stress HCAs experience, whether and how this stress affects their health, and whether stress and other health issues affect their ability to provide care for their older clients. A national survey conducted in 2007 contributed to our understanding of the working conditions of home health aides employed in Medicare-funded home health agencies, but excluded HCAs working in the non-medical home care sector.18

The gap in knowledge about HCAs is critical for health care of older adults with disabilities for several reasons. First, HCAs constitute one of the fastest growing occupations in the United States.19–22 The occupation of HCAs is projected to add the most new jobs of any occupation between 2012 and 2022 (580,800 jobs, 49% growth). Home care aides are hired privately by their clients or employed by home care agencies that specialize in non-medical housekeeping or personal assistant services. The non-medical home care sector evolved from the visiting housekeeper program for the needy funded by Medicaid and other public funds or private pays, and operates based on a social service model.23 In this care setting, family members may become paid caregivers for older home care recipients, depending on the rules and regulations of the state of residence. Furthermore, HCAs work in a setting without Medicare’s skilled care need requirements or time restrictions.24–27 Thus, HCAs are more likely than home health aides to care for their clients for an extended period and to develop long-term close relationships with their clients. Accordingly, HCAs’ work environment may be qualitatively different from that of home health aides who perform similar tasks as HCAs. Data on home health aides who typically work in Medicare-funded agencies that are licensed to provide medical home health care19 cannot be simply extrapolated to describe HCAs.

Second, despite working in clients’ homes without medical supervision, HCAs tend to care for clients with high health needs. Home care aides in Medicaid-funded home care programs often work with clients who are eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare. These so-called “dual eligibles” have more chronic conditions than typical Medicare beneficiaries.28 Frequently underserved throughout their life course, dual eligible may be dealing with complications of untreated or undertreated chronic conditions in later life. While home health aides typically care for Medicare home health users who are concurrently receiving skilled nursing or therapy services, HCAs care for clients who may not be under active medical care. Thus, HCAs may be more likely than home health aides to care for clients who have untreated or uncontrolled medical conditions and who lack opportunities to engage in health-promoting activities to prevent further health declines.

Third, HCAs work by themselves in the private homes of older clients. Their work and work environment cannot be easily observed by their supervisors, although safety and health interventions are challenging to implement. This distinguishes their work from caregivers working in nursing homes or hospitals. Home care aides are older and lower-income8 than nursing home or hospital-based aides, are less likely to have fulltime employment, and may face more challenges in their personal and work lives than other health care workers.

The goal of this study was to enhance our understanding of HCAs informed by the stress process perspective. This study focused on HCAs’ health in their work and life contexts in order to explore their current and potential roles for promoting the health of older adults with long-term care needs in a Medicaid home care program. To learn more about these challenges and their implications for HCAs’ health-promoting roles for their older clients and for themselves, our research listened to the voices of HCAs, who naturally have intimate knowledge of, and experience with, HCAs’ health, work, and life contexts. Without adequate understanding of HCAs who provide home care services directly to their clients, it would be difficult to assess and improve home care services for underserved populations aging with disabilities.

Methods

Overview and contexts.

Six focus groups were conducted with HCAs who care for older adults receiving in-home service programs in the city of Chicago, mainly through the Community Care Program (CCP), which is funded by Medicaid and Illinois general revenue funds and administered by the Illinois Department on Aging. The state contracts with for-profit and not-for-profit home care agencies to provide CCP services to Illinois residents aged 60 years or older with long-term care needs, who are U.S. citizens or legal aliens with non-exempt assets of $17,500 or less (excluding home, car, and personal furnishing). All HCAs who provide CCP services must be employed and trained by home care agencies contracted with Illinois Department on Aging. CCP clients can choose their family members or relatives as their HCAs only if they are formally hired by contracted home care agencies after successfully completing state-mandated pre-service training provided by home care agencies. Under CCP, no HCAs are self-employed nor hired directly by their clients.

Approximately two thirds of CCP’s HCAs in Illinois are unionized, a quarter of whom work in the Chicago area. Partnership with the Service Employees International Union (SEUI) Healthcare Illinois & Indiana (previously SEIU Local 880), which is the largest union of health care and home childcare workers in the Midwest, allowed us to recruit otherwise difficult-to-reach HCAs from multiple employers. We used the methods that the labor union consider most effective in reaching HCAs: distribution of flyers, telephone calls, and direct contact by the union staff (1,300 flyers mailed, 1,000 flyers distributed, 350 phone calls, and 40 hours of door-knocking). Our sample did not include non-unionized HCAs such as HCAs employed by agencies that serve limited English-speaking older adults (approximately 20% of all CCP HCAs). The study was reviewed for human subjects’ protection and approved by the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) Institutional Review Board. The participant recruitment process was monitored via weekly phone conferences by the UIC research team and the director of SEIU Member Training and Education Center. Interested HCAs were assigned to focus groups on a first-come, first-served basis. Those who had signed up received a reminder letter one week prior to the focus group, followed by a reminder phone call one to two days before the focus group. Each participant received a $25 incentive payment. Forty-five HCAs participated in one of six focus groups on health promotion.

Each 90-minute focus group, held in a conference room at the union’s main offices, was preceded by a 60 minute session including an ice-breaking reception with refreshments, an overview of the study, the informed consent process, and a brief self-administered survey to capture the participants’ demographic and health characteristics. The Principal Investigator (NM) moderated each focus group, during which a research assistant (VL) took detailed notes. The focus group guide included 10 main questions (and additional probing questions) about HCAs’ health (e.g., What makes you feel healthy? Tell us about any work situations that have affected your health.), HCAs’ own health promotion activities (e.g., What do you currently do to take care of your health?), and HCAs’ health-promoting role for older clients (e.g., How do you currently contribute to the health and well-being of your clients? What do you think of expanding your role to promote health among your older clients?). Immediately following each focus group, the research group (NM, VL, and occasionally a co-investigator, JZ or RS) held a debriefing session to identify major themes and unexpected or noteworthy findings. The research team agreed that a data saturation point was reached after five focus groups. We presented the summaries of the five focus groups at a validation focus group.12 The validation focus group participants (N=7, including one who participated in one of the earlier focus groups) agreed that we “got it right” and “got it all” and provided additional information on the selected themes. All six focus groups were professionally transcribed.

Data analysis.

Two of the authors (NM and VL) independently coded the professionally transcribed data to uncover themes and concepts.29 After reading two transcripts, NM and VL met to discuss findings and devised an initial coding scheme. The stress process framework as well as our research questions guided the development of major categories of codes (e.g., stressors, enduring health outcomes, health outcomes, health promotion activities) and subcategories. After reading the rest of the transcripts, NM and VL updated the coding scheme. We extracted all the data that described stressors in HCAs’ work and life contexts, health, and coping resources and strategies as well as HCAs’ attitudes towards health and health promotion. Upon further analysis of themes, we identified broader unifying concepts related to our research questions and incorporated them into the summary tables. Post-focus group debriefing meetings within the research team and the debriefing focus group with HCAs, as mentioned above, minimized conflicting results along the way. For any minor conflicting results that had emerged, the two main coders (NM and VL) discussed the results and, if they were not resolved, the third member of the team provided input to produce consensus. ATLAS.ti assisted our analysis.30

Results

Participant characteristics.

Focus group participants (N=45) were typically middle-aged or older African American women with high school-level education: 51% were aged 50 years or older, 98% African American women, and 58% with high school education, as summarized from the pre-focus group survey (see Table 1). The profile of these English-speaking HCAs is consistent with previous studies14,31 and with what is expected from the historical development of the non-medical home care industry in Chicago.23 The HCA participants had worked in home care for seven years, on average. The average caseload per week was 1.5 clients. The majority (69%) were providing services to clients assigned by their employers, 24% their family (or friends), and 7% both. Eighty percent of HCAs reported one or more conditions from the list of 12 health conditions (and “others” where the respondent was asked to specify a condition),32, 33 and 47% had multiple conditions (up to seven conditions [4%]). Hypertension (47%), arthritis (34%), asthma (27%), and allergic rhinitis (27%) were most common conditions. The frequencies and patterns of chronic conditions generally mimic the national estimates of middle-aged to elderly African American women in the United States.34 The smoking rate (48.9%) was more than double the rate among all Americans.35

Table 1.

Focus Group Participants’ Sociodemographic, Job and Health Characteristics (N=45)

| Variables | Mean or Percent (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age: 18–29 | 4.4 | |

| 30–49 | 44.4 | |

| 50–64 | 49.0 | |

| 65+ | 2.2 | |

| Gender: female | 97.8 | |

| Race: Black | 97.8 | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 2.2 | |

| Education | ||

| Some high school | 13.3 | |

| High school diploma or GED | 44.4 | |

| Some college | 26.7 | |

| Associate’s degree | 6.7 | |

| Bachelor’s degree or more | 8.9 | |

| Job tenure | ||

| Home care (years)1 | 7.0 | (6.1) |

| Current employer (years) | 5.4 | ( 4.9) |

| Caseload | ||

| Number of clients/day | 1.5 | (.7) |

| Number of clients/week | 1.8 | (1.3) |

| Type of clients | ||

| Family (or friends) | 24.4 | |

| Non-family | 68.9 | |

| Both | 6.7 | |

| Health conditions2 | ||

| Hypertension | 46.7 | |

| Arthritis | 34.1 | |

| Asthma | 26.7 | |

| Allergy | 26.7 | |

| Eye Problems | 13.3 | |

| Ulcer | 8.9 | |

| Anemia | 8.9 | |

| Heart | 6.7 | |

| Diabetes | 4.6 | |

| Urinary Problems | 4.4 | |

| Other conditions | 8.9 | |

| Smoking everyday | 31.1 | |

| some days | 17.8 | |

| Back pain | 64.4 | |

| Knee pain | 57.8 | |

| Neck/shoulder pain | 55.6 | |

| Arm/elbow/hand pain | 35.6 | |

| Hip pain | 33.3 | |

Notes: SD=Standard deviation.

Ranges from less than a year to 27 years. 22% had worked in home care for less than 3 years, 22.2% for 3 to 5 years, 36% for 5 to 10 years, and 20% for 10+ years.

The number of health conditions ranged from 0 to 7 (mean=1.89, median=1; out of 13 conditions).

Perceived health.

Stress emerged as the most salient theme in focus group discussions about HCAs’ health. Home care aides reported feeling stressed regardless of topics under discussion. Stress themes dominated HCAs’ discussion of their health conditions, including mental health (e.g., depression), chronic conditions (e.g., hypertension, asthma, arthritis, and diabetes), musculoskeletal problems (e.g., knee and back injuries), and dental problems. Home care aides used the term “stress” broadly or vaguely to refer to intricately intertwined work and life stressors.

Stressors.

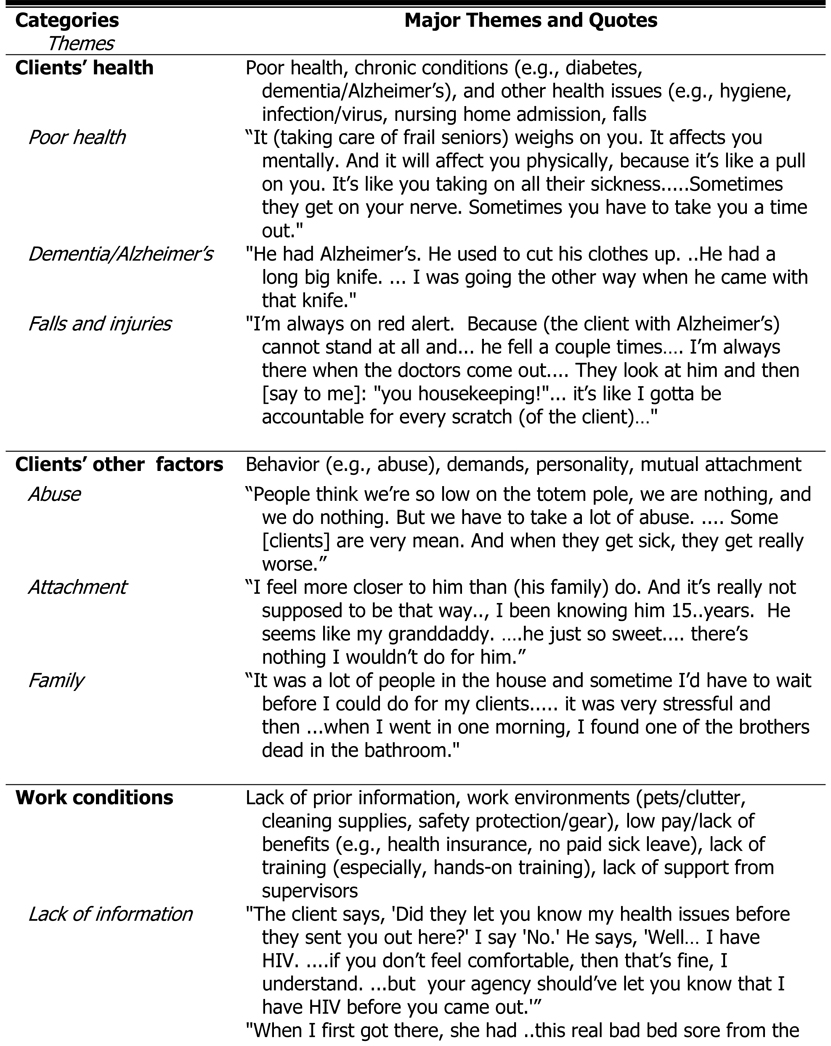

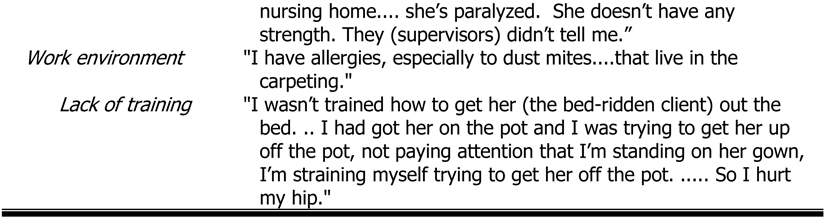

Home care aides described how home care work and their non-work lives triggered their stress process. Work stressors encompassed HCAs’ specific clients as well as their work conditions. Themes related to clients involved clients’ health issues (health in general; chronic conditions, including dementia/Alzheimer’s; and other issues such as infection/virus, nursing home admission, falls), as well as non-health issues (clients’ offending behavior, demands, personality, mutual attachment, and family). Work conditions included lack of prior information, work environments (pets/sanitation/clutter; lack of safety protection/gear), and low levels of benefits and supports (low pay/lack of benefits; lack of training, especially hands-on training; and lack of support from supervisors). Table 2 provides a summary of major themes of work-related stressors, supported by quotations from HCA focus group participants that represent each of the major themes.

Table 2.

Perceived Work-related Stressors among Home Care Aides: Themes and Quotes

| |

|

Clients’ health.

Regarding work-related stressors, clients’ poor health and physical functioning were among the most frequently mentioned stressors. Taking care of frail home care clients is inherently stressful, as exemplified by a statement, “It weighs on you” (see Table 2).” Even if HCAs do not provide medical care, they routinely encounter clients’ medical conditions, during such tasks as routine cleaning or meal preparation for a client with diabetes. Unattended medical problems are not uncommon among disadvantaged clients in Medicaid-funded, non-medical home care, and thus HCAs could encounter clients with seriously advanced medical conditions. One participant described a client with a serious and untreated leg infection:

When I pushed the door open to go up to her house, it’s this awful smell. .… I turned around. It made me sick‥…I attempt to turn back around and go up there. The whole time I’m walking up the stairs, you know I’m gagging.… I knocked on her door. Her brother answered the door. She was sitting up there…and she had an infection all in her legs and that was that smell.

Clients’ failing cognitive function challenged HCAs mentally and physically. For example, an HCA reported her client accusing her of stealing something that the client misplaced. An HCA reported stress because she felt responsible for repetitive scratches that her client with dementia incurred during the HCA’s absence. Home care aides were aware of potential infections and infestations (naming methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA, and bed bugs) and worried about transmission to themselves and their family.

Clients’ behavior and family.

As shown in Table 2, clients’ non-health factors, such as clients’ abusive or offending behavior (e.g., treating a HCA as a maid), excessive demands (e.g., moving heavy furniture), and difficult personalities constituted major stressors. A sense of attachment to clients could be positive or negative, as seen in the grief an HCA reported when her client entered a nursing home and later died. Clients’ families could be a source of stress. For example, clients’ family members would interrupt HCAs’ work routine or make demands on HCAs.

Work conditions and support.

Lack of prior information about work environments was among the most frequently mentioned stressors related to work conditions. Home care aides often received little information about their clients’ health or about home and neighborhood conditions prior to their first visit. Home care aides described how they encountered surprises on their first visit (e.g., a paralyzed client with a large bedsore, see Table 2). Lack of information generated stress because HCAs were unable to prepare themselves beforehand for challenging situations.

HCAs work environments might include dust, pets, and clients’ smoking that could cause adverse health consequences for HCAs with asthma or allergic rhinitis.

Working conditions and work support (e.g., training, pay and benefits, support from supervisors) affect HCAs’ stress in two ways. First, HCAs explicitly indicated that insufficient work-related benefits, especially low pay, lack of health insurance, and lack of understanding/appreciation from supervisors, are stressors. Second, work supports (e.g., supervisor showing appreciation for HCAs’ work, training about how to deal with difficult situations on the job) lessen the effects of inherently stressful work, while the absence of such supports exacerbates those effects. While all HCAs received pre-service and in-service training provided by their employers as mandated by the state, they wanted more hands-on practical training.

Home care aides’ consistent requests for more training, especially hands-on training to prepare themselves appropriately for the job, is noteworthy. They argued that lack of training resulted in not knowing what to do when needs arise. Such uncertainties not only resulted in poor care for their clients but also contributed to HCAs’ stress.

Positive and negative work factors.

Home care work generated not only stress but also positive mental health effects, as seen in an HCA’s statement: “I get a rush out of knowing that I can make somebody else happy with what I’m doing and that they appreciate it.” Mutual attachment between the HCA and the client generated both positive and negative emotions, such as warmth and satisfaction or sorrow and anxiety.

Non-work-related stressors.

Home care aides’ personal and family factors had accumulated over HCAs’ life course. Home care aides’ family caregiving responsibilities were among the most frequently mentioned. One HCA said,

My biggest stress is how I’m gonna raise four motherless children, my [deceased] daughter’s children. And that’s the biggest stress on me because they are a new generation. They are not like my kids [laughs].

Deaths in the family were another frequently mentioned theme.

Thirteen years ago I lost my husband, he committed suicide. I was at home. Two days after that, I lost my grandmother. About six months before that, I lost my cousin. About five months before that, I lost my brother. And I’ve had a stressful life for about 13 years now…

I lost my mom…about four years now, but I never got closure because …. the doctor didn’t even know what happened… And then I lost my brother.

“Back to back deaths in the family” was mentioned as a source of stress in 3 of the 6 focus groups.

Gun-related deaths and injuries were frequently cited. One of HCA participants shared, “I got shot in my back and the bullet stopped right next to my spine.”

Another described.

My brother got shot 5 times on the front porch and it’s just a lot of back to back (deaths in the family). He died in my arms---so that stays with me a lot of time. I think it over a lot.

However, not all violence was gun related. One participant described her son’s ordeal:

… they tied him to a chair. (crying) They beat him … and he almost died. He was in a coma for a whole month. But he alright now. God is good.

Intertwined work and life stressors affect HCAs’ health and client services.

Multiple work-related stressors, intertwined with non-work stressors mentioned above, triggered short-term physical, psychological, physiological, and behavioral conditions that may lead to enduring health conditions. Home care aides’ own intertwined physical and mental health factors affect, and could be affected by, caregiving work and personal stressors over time.

I don’t want to leave this client because I got kind of attached. But it’s too much stress… I have to take medication. I have skipped medicine…And then my health fail and then I’m down. Then…worrying about that person so hard and then worrying about my other personal things, I get into this depression thing. … I’m really on a kick if that person happens to get ill‥…You know, how can you not get attached? You see them every day, two or three hours or more. I don’t know if I could do that for another three years. And with him with that wheelchair, all that lifting and I been in a car accident in the last couple years and I got hurt. You know and it’s just like something I’m neglecting on myself because I’m so busy trying. And then you have a lot of pressure from [the client’s] family that don’t come around. …He ‥ fell a couple times. I got hurt a couple times trying to lift him.

Long-term health consequences.

Home care aides kept working despite health problems (e.g., pain, asthma, high blood pressure), because they needed to pay their bills and had no paid leave, as shown in the following two HCAs’ quotations:

[Injuries, blood pressure, stress, arthritis do not prevent ability to work]. Because you got to go to work. If you do not go to work, you don’t get paid. No bills get paid. Nothing gets done. So you still mentally tell yourself, ‘Straighten it up!’

If you don’t have insurance … no paid days off, then what you do? You know that rent got to be paid. And you got kids in college that got to be paid. You forgetting the pain even though you steady in pain.

A minority of HCAs reported rare occasions of missing work due to medical problems (exacerbated knee injury, flu, doctor’s appointment) or family needs (death in the family, a child with severe asthma). Home care aides claimed that their health issues did not affect their ability to assist clients, with rare exceptions (e.g., if their back goes out). However, multiple stressors would lead to enduring psychological stress and eventually to burnout, as reported by an HCA who could no longer be patient with her client and by an HCA who said, “It [stress] takes a toll on how well you take care of [my client, who is my mother].”

The doctor told me that [my] back is just wear and tear now… But I keep on going….It’s hurting right now.

HCAs’ own health promotion behavior, facilitators and barriers.

Home care aides’ interest in health promotion for themselves was high. For example, an HCA said, “[Health promotion is] very important‥…an unhealthy person can’t function, you can’t perform your duties.” Health promotion activities that HCAs’ reported doing included physical activities (walking, group exercise, exercise on the job), self-care (diet, self-diagnosis, home remedy book, smoking cessation, safety precautions such as washing hands, wearing gear to prevent injuries), seeking medical care/medication, relaxation (taking it easy, relaxation/meditation, take a time out), and others (e.g., religion).

As expected, support and encouragement from the doctor, family, and friends, as well as group health promotion programs facilitated HCAs’ health-promoting behavior. Barriers to health promotion included “too tired after work,” no time, stress, lack of motivation, and HCAs’ own health conditions. Interestingly, adverse conditions, such as enduring health problems (“tired of being sick”) and lack of benefits (e.g., health insurance), motivated HCAs to engage in health promotion activities. Limited finances motivated an HCA to avoid eating out [fast food]. Commitment to their work and their client could motivate HCAs, as shown in statements: “Who is going to help my client if I am sick?” and “If we’re not healthy, then we cannot take care of our clients or our families.” Home care aides’ response to questions about their own health needs often centered instead on the needs of their clients.

HCAs’ current and potential roles to promote health in older clients.

Home care aides were generally motivated to play health-promoting roles for clients. Home care aides positively responded when asked whether they were willing to expand their roles to help promote their clients’ health and function.

In fact, focus groups revealed that HCAs had been playing important roles in promoting health and function in home care clients already, although health promotion was not part of their job descriptions. Home care aides reported that they had helped their clients with their medical care, not by providing direct medical care but by enhancing access. For example, HCAs regularly reminded clients to take medication, and helped access therapy and physicians (e.g., identifying needs, locating therapists, driving for a medical appointment). Equally important, HCAs mentioned their provision of social support (e.g., companionship, encouraging socialization) to enhance clients’ mental health. Other areas where HCAs reported their contribution to promoting clients’ health included diet (e.g., cooking meals, encouraging healthy eating), observation (e.g., home environmental scan for safety), exercise, provision of mental stimulation (games), and taking care of clients’ hygiene.

Home care aides sometimes reported doing what was beyond the care plan (detailed instruction of what services HCAs should provide). In particular, several HCAs mentioned that they had helped their clients walk and do other forms of mild exercise: “[I] help them to exercise as much as they can so their body won’t be so stiff—to move their legs and arms and just try to get their body to move around so they won’t be so stiff. And walk them a little bit as far as they could walk. [Without her employer ‘s request] I did it myself.”

Barriers for HCAs to promote health in their older clients included clients’ resistance to change: “But sometimes they [clients] don’t want to do it [eat healthy]. You could give them your advice. But you can’t tell a grown person what to do.”

Discussion

In-home care of older adults with disabilities has grown in importance.36 However, limited information is available on paid caregivers of older adults in publicly funded home care programs. This project aimed to enhance the understanding of HCAs’ health in relation to their work and life contexts by conducting focus groups with HCAs in a Medicaid-funded home care program in a large U.S. city. The HCA participants were mostly middle-aged or older African American women, many of whom had multiple chronic health conditions. Home care aides experienced work and life-related situations that led to physical, mental or emotional strain perceived as sufficient to produce adverse health outcomes. Work support (or lack thereof) moderated perceived stress. Although generally consistent with what is known as the stress process,16, 37, 38 our focus group research allowed HCAs’ voices to reveal the intricately intertwined nature of work and life stressors.

In their work, HCAs become emotionally attached to their clients, some of whom are also family or friends. The client’s care needs assessed by the state determine the number of HCA work hours per client, which rarely exceed four hours per session. Home care aides in this study experienced stressors from challenges in their own homes as well as at work. Focus groups allowed us to capture the stress process, especially the connections among various components of the process, through HCAs’ stories that encompassed their life course. For example, in the discussion of HCAs’ strategies for stress coping and health promotion, HCAs described how personal experiences, such as violent crime (“I was shot in the back”) or chronic illness (“I was sick of being sick”), triggered HCAs to change their behavior (e.g., initiating walking for exercise). These findings emphasized the importance of understanding the stress process from the life course and ecological perspectives.39, 40

This study has limitations. Our focus group participants were English-speaking, mostly African American HCAs recruited through the labor union in a large U.S. city. Those participants were willing to take the time for the study and, accordingly, may have been more motivated for their work than others. Although our findings may not be applicable to HCAs in other settings, this study illuminated work and life contexts that affect HCAs’ health as well as their interest and potential to assume health-promoting roles for themselves and their clients. Another limitation is that our study involved active HCAs only, which might potentially introduce a selection bias. Specifically, this study does not reflect the views of those who had left the job and might have additional concerns. Future research should incorporate views of non-active HCAs and examine variations in stress process in relation to HCAs’ job tenure and HCA-client relationships (e.g., caring for family as an HCA).

Home care aides constitute one of the fastest growing segments of the health care workforce and an underserved occupational population with significant health-related issues. If we understand how deeply the HCAs’ own life contexts and health are interconnected with their work, we can better enable HCAs to promote their clients’ health as well as their own health.

Home care aides, like other frontline health workers, constitute an understudied human resource in health and social service delivery systems.15, 41 Home care aides’ abilities could be evaluated in formal interventions aimed at maintaining or improving the health and function of frail, home-bound older adults in publicly funded home care programs. Thousands of HCAs already participate in continuing education, which is mandated by some states (including Illinois). A significant portion of this workforce have already established long-term relationships with low-income homebound seniors, a difficult-to-reach population with high health needs and multiple chronic conditions. Home care aides often share culture (language, social norms, food) and life experience with their economically disadvantaged clients in public home care programs, as evidenced by the fact that one third of HCAs in our study cared for their family or friends. Shared culture is especially important for home care that is intimately linked with clients’ everyday lives. Home care aides are well-positioned to carry out sustainable health-promoting activities and chronic disease management for their clients.

Home care aides are also interested in participating in hands-on training to learn to expand their abilities to help their clients. On the one hand, the HCA workforce experiences high turnover similar to that of other frontline healthcare workers.42, 43 On the other hand, like other frontline healthcare workers, HCAs who are experienced, motivated, and committed to their profession remain in the profession for many years.44

With the increasing numbers of older Americans and emphasis on home and community-based care, home care needs and demand will continue to grow. Promoting health, function, and independence among homebound seniors at risk for nursing home admission is important both for older adults’ well-being and for curbing the skyrocketing long-term care costs in the U.S. Our research demonstrated that HCAs are motivated to play health-promoting roles for homebound clients.

Without the knowledge of how intricately intertwined HCAs’ work and life stressors are, it is difficult for policymakers and home care providers to develop effective strategies to promote the work of HCAs and improve the quality of publicly funded home care. Policymakers and home care providers should continue to enhance their understanding or HCAs’ work and life contexts, offer job training opportunities and career ladders, and provide pro-rated but meaningful benefits, such as paid sick leave and vacation time, and health care and retirement benefits.45 Research is needed to identify approaches to provide emotional support to HCAs in stressful situations. Also needed is research to determine whether job task enrichment to realize HCAs’ full capacity would help reduce job stress. The HCA voices heard in this article revealed that HCAs would welcome opportunities to enhance their caregiving skills as well as their own health and well-being. Building health promotion into HCAs’ job description and training programs may offer policymakers and providers the opportunity to address the needs of the HCAs as well as of their clients.46 Such efforts to promote the health of community-dwelling frail older persons and the well-being of home care workers themselves deserve to be explored, evaluated, and potentially disseminated.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Midwest Roybal Center for Health Promotion [grant number 5P30AG022849–05] and the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health [grant number 3T42 OH008672]. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the funding agencies. The authors thank Myra Glassman, Angela Mojekwu, and Margaret Raines for their collaboration and support; Drs. Shakirudeen Amuwo, Lorraine Conroy and Leslie Nickels† of the Blood Exposure and Primary Prevention in Home Care research team; home care aides who participated in our study; and Dr. Marshall H. Chin and Tracy Weiner and for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper.

†Deceased

Contributor Information

Naoko Muramatsu, Associate Professor at Community Health Sciences at School of Public Health and a Fellow at the Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago..

Rosemary K. Sokas, Professor at Human Science at the School of Nursing and Health Studies, Georgetown University..

Valentina V. Lukyanova, Research Analysist at American Association of Nurse Anesthetists. She was affiliated with School of Public Health at University of Illinois at Chicago at the time of the project implementation..

Joseph Zanoni, Director of Continuing Education and Outreach at Great Lakes Center for Environment and Occupational Health and Safety at University of Illinois at Chicago..

REFERENCES

- 1.Wolff JL, Kasper JD. Caregivers of frail elders: updating a national profile. Gerontologist. 2006. June;46(3):344–56. Epub 2006/05/30. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spillman BC, Pezzin LE. Potential and active family caregivers: changing networks and the “sandwich generation”. Milbank Q. 2000. September;78(3):347–74. Epub 2000/10/12. PMID: ; PMCID: PMC2751162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freedman VA, Spillman BC. Disability and care needs among older Americans. Milbank Q. 2014. September;92(3):509–41. Epub 2014/09/10. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12076. PMID: ; PMCID: PMC4221755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muramatsu N, Yin H, Campbell RT, Hoyem RL, Jacob MA, Ross CO. Risk of nursing home admission among older americans: Does states’ spending on home- and community-based services matter? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007. May;62(3):S169–78. Epub 2007/05/18. doi: 62/3/S169[pii]. PMID: ; PMCID: PMC2093949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muramatsu N, Hoyem RL, Yin H, Campbell RT. Place of death among older Americans: does state spending on home- and community-based services promote home death? Med Care. 2008. August;46(8):829–38. Epub 2008/07/31. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181791a7900005650-200808000-00010[pii]. PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaiser Family Foundation. Dual Eligibles as a Percent of Total Medicare Beneficiaries [cited 2013 January 4]. Available at: http://kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/duals-as-a-of-medicare-beneficiaries/.

- 7.Yamada Y. Profile of home care aides, nursing home aides, and hospital aides: Historical changes and data recommendations. Gerontologist. 2002. April;42(2):199–206. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montgomery RJV, Holley L, Deichert J, Kosloski K. A profile of home care workers from the 2000 Census: How it changes what we know. The Gerontologist. 2005. October;45(5):593–600. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaye HS, Chapman S, Newcomer RJ, Harrington C. The personal assistance workforce: trends in supply and demand. Health Aff (Millwood). 2006. Jul-Aug;25(4):1113–20. Epub 2006/07/13. doi: 25/4/1113[pii]10.1377/hlthaff.25.4.1113. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amuwo S, Lipscomb J, McPhaul K, Sokas RK. Reducing occupational risk for blood and body fluid exposure among home care aides: an intervention effectiveness study. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2013;32(4):234–48. Epub 2014/01/01. doi: 10.1080/01621424.2013.851050. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amuwo S, Sokas RK, McPhaul K, Lipscomb J. Occupational risk factors for blood and body fluid exposure among home care aides. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2011. April;30(2):96–114. Epub 2011/05/19. doi: 10.1080/01621424.2011.569690937657592[pii]. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amuwo S, Sokas RK, Nickels L, Zanoni J, Lipscomb J. Implementation and evaluation of interventions for home care aides on blood and body fluid exposure in large-group settings. New Solut. 2011;21(2):235–50. Epub 2011/07/08. doi: 10.2190/NS.21.2.g. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delp L, Wallace SP, Geiger-Brown J, Muntaner C. Job stress and job satisfaction: home care workers in a consumer-directed model of care. Health Serv Res. 2010. August;45(4):922–40. Epub 2010/04/21. doi: HESR1112[pii]10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01112.x. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipscomb J, Sokas R, McPhaul K, Scharf B, Barker P, Trinkoff A, et al. Occupational blood exposure among unlicensed home care workers and home care registered nurses: are they protected? Am J Ind Med. 2009. July;52(7):563–70. Epub 2009/05/30. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20701. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zanoni J, Kauffman K, McPhaul K, Nickels L, Hayden M, Glassman M, et al. Personal care assistants and blood exposure in the home environment: focus group findings. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2007. Summer;1(2):125–31. Epub 2007/01/01. doi: S1557055X07201251[pii]10.1353/cpr.2007.0017. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the Stress Process: An Overview of Concepts and Their Measures. The Gerontologist. 1990. October;30(5):583–94. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker E, Israel BA, Schurman S. The integrated model: implications for worksite health promotion and occupational health and safety practice. Health Educ Q. 1996. May;23(2):175–90. Epub 1996/05/01. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics. National Home and Hospice Care Survey, 2007. [September 2, 2018]. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhhcs/about_nhhcs.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. Occupational Outlook Handbook, Home Health Aides and Personal Care Aides Available at: https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/home-health-aides-and-personal-care-aides.htm.

- 20.Institute of Medicine. Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2008. Available at: http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/reports/2008/retooling-for-an-aging-america-building-the-health-care-workforce.aspx [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaye HS, Harrington C, LaPlante MP. Long-term care: who gets it, who provides it, who pays, and how much? Health Aff (Millwood). 2010. Jan-Feb;29(1):11–21. Epub 2010/01/06. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0535. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richards E, Terkanian D. Occupational Employment projections to 2022. Monthly Labor Review [Internet]. 2013; (December):[1–44 pp.]. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2013/article/pdf/occupational-employment-projections-to-2022.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boris E, Klein J. Caring for America: Home Health Workers in the Shadow of the Welfare State. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195329117.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dean O, Lind K. Understanding Medicare’s home health benefit. Spotlight [Internet]. 2017. November; (30). Available at: https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2017/11/understanding-medicares-home-health-benefit.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Day T. About Long Term Care At Home: Care Provided by Family or Others at Home [cited 2018 September 2, 2018]. Available at: https://www.longtermcarelink.net/eldercare/long_term_care_at_home.htm.

- 26.O’Connor M, Hanlon A, Naylor MD, Bowles KH. The impact of home health length of stay and number of skilled nursing visits on hospitalization among Medicare-reimbursed skilled home health beneficiaries. Res Nurs Health. 2015. August;38(4):257–67. Epub 2015/05/21. doi: 10.1002/nur.21665. PMID: ; PMCID: PMC4503505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare & Home Health Care. Washington, D.C. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HomeHealthQualityInits/Downloads/HHQIHHBenefits.pdf.

- 28.Coughlin T, Waidmann T, O’Malley Watts M. Where Does the Burden Lie? Medicaid and Medicare Spending for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries. Washington, D.C.: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, 2009. Available at: Medicaid and Medicare Spending for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 30.ATLAS.ti: Qualitative Data Analysis. (n.d.). Available at: http://atlasti.com/.

- 31.Seavey D, Marquand A. Caring in America--A Comprehensive Analysis of the Nation’s Fastest-Growing Jobs: Home Health and Personal Care Aides: PHI; 2011. Available at: http://phinational.org/sites/phinational.org/files/clearinghouse/caringinamerica-20111212.pdf.

- 32.Liang J, Bennett J, Whitelaw N, Maeda D. The structure of self-reported physical health among the aged in the United States and Japan. Med Care. 1991. December;29(12):1161–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sastre J, Madero MF, Fernandez-Nieto M, Sastre B, del Pozo V, Potro MG et al. Airway response to chlorine inhalation (bleach) among cleaning workers with and without bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Am J Ind Med. 2011. April; 54(4): 293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ward BW, Schiller JS. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions among US adults: estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013. April;10:E65 Epub 2013/04/27. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120203E65 [pii]. PMID: ; PMCID: PMC3652717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agaku IT, King BA, Dube SR. Current cigarette smoking among adults - United States, 2005–2012. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. August 24, 2014;63(2):29–34. PMID: PMCID: PMC4584648 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buhler-Wilkerson K. Care of the chronically ill at home: An unresolved dilemma in health policy for the United States. Milbank Q. 2007. December;85(4):611–39. Epub 2007/12/12. doi: MILQ503[pii]10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00503.x. PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thoits PA. Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51 Suppl:S41–53. Epub 2010/12/22. doi: 51/1_suppl/S41[pii]10.1177/0022146510383499. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pearlin LI, Lieberman MA, Menaghan EG, Mullan JT. The stress process. J Health Soc Behav. 1981. December;22(4):337–56. Epub 1981/12/01. PMID: . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pearlin LI, Schieman S, Fazio EM, Meersman SC. Stress, health, and the life course: Some conceptual perspectives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005. June;46(2):205–19. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600206. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elder Glen H Jr, Richard CR The life-course and human development: An ecological perspective. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1979. March;2(1):1–21. doi: 10.1177/016502547900200101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sokas RK, Cloonan P, Braun BI. Exploring front-line hospital workers’ contributions to patient and worker safety. NEW SOLUTIONS: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy. 2013. January;23(2):283–95. doi: 10.2190/NS.23.2.e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feldman PH. Work life improvements for home care workers: impact and feasibility. Gerontologist. 1993. February;33(1):47–54. Epub 1993/02/01. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Banaszak-Holl J, Hines MA. Factors associated with nursing home staff turnover. Gerontologist. 1996. August;36(4):512–7. Epub 1996/08/01. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rakovski CC, Price-Glynn K. Caring labour, intersectionality and worker satisfaction: an analysis of the National Nursing Assistant Study (NNAS). Sociol Health Illn. 2010. March;32(3):400–14. Epub 2009/11/07. doi: SHIL1204[pii]10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01204.x. PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stone RI. The Direct Care Worker: The third rail of home care policy. Annual Review of Public Health. 2004. April 21;25(1):521–37. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.102802.124343. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muramatsu N, Yin L, Lin TT. Building health promotion into the job of home care aides: Transformation of the workplace health environment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017. April;14(4). Epub 2017/04/06. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14040384. PMID: ; PMCID: PMC5409585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]