Abstract

Introduction:

Efficacy and safety are key aspects when choosing therapies for patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). While several randomized trials and indirect comparisons have informed the comparative efficacy of medications, there has been limited synthesis of safety of different agents.

Areas covered:

We focus on the overall and comparative risk of serious and opportunistic infections and malignancy of biologic and immunosuppressive therapy in IBD, based on randomized trials, open-label extension and registry studies and real-world comparative observational studies.

Expert opinion:

Comparative safety of pharmacotherapy for IBD should be viewed in conjunction with efficacy and in the context of treatment strategies/approach, rather than in the context of specific agents used. TNFα antagonists may be more immunosuppressive than non-TNF-targeted biologic agents, and increase the risk of systemic infections. Most consistent risk factors for serious infections include use of combination therapy with immunosuppressive agents and/or corticosteroids, moderate to severe disease activity, and older age. TNFα antagonists may also be associated with an increased risk of lymphoma, especially when combined with thiopurines. Real-world comparative safety studies, especially with newer biologic agents, are warranted to inform decision making.

Keywords: Cancer, Infection, lymphoma, immunosuppression, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease

1. INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are associated with significant morbidity and high burden of hospitalization. A subset of patients with moderately to severely active disease will often require corticosteroids, biologic and/or immunosuppressive agents. In a nationally representative cohort study, we estimated that high-need, high-cost patients with IBD spend approximately 3.7 days in the hospital per month, and serious infections are one of the leading causes for hospitalization.1 Both underlying active disease, as well as treatment with immune suppressing therapy contributes to an increased risk of serious and opportunistic infections in these patients.2–5 Apart from infection, risk of cancer with treatment is one of the most feared complications among patients, though that risk may be overstated. With increasing options available, in addition to comparative efficacy and speed of onset of action, comparative risk of treatment-related complications is an important attribute of shared decision-making regarding treatment choice in patients with IBD.

In this review, we evaluate the overall and comparative safety of approved biologic agents and immunosuppressive therapies in patients with IBD. Using evidence from randomized trials with long-term open-label extension, registry studies and real-world observational comparative studies, we primarily focus on the risk of serious and opportunistic infections and malignancy.

2. SERIOUS AND OPPORTUNISTIC INFECTIONS

2.1. Tumor necrosis factor-(TNF)α antagonists

TNF is a key pro-inflammatory cytokine in IBD that is mainly produced by activated macrophages and T lymphocytes.6 TNF induces other pro-inflammatory cytokines including interleukin-1 and interleukin-6, enhances leukocyte migration by inducing expression of adhesion molecules, induces acute phase reactants, and inhibits apoptosis of inflammatory cells. TNFα antagonists, by binding to membrane-bound and soluble TNF, induce destruction of immune cells by antibody-dependent cellular toxicity, induce T-cell apoptosis by binding to membrane-bound TNF, and neutralize the effects of soluble TNF.7 Four TNFα antagonist agents have been approved for the management of IBD – infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol (exclusively for Crohn’s disease [CD]) and golimumab (exclusively for ulcerative colitis [UC]).7 Infliximab is a chimeric monoclonal IgG1 antibody against TNFα composed of 75% human and 25% murine sequences. It is administered intravenously, over 1–3 hours, with standard weight-based dosing of 5mg/kg at weeks 0, 2 and 6 for induction, followed by 5mg/kg every 8 weeks for maintenance of remission. Adalimumab and golimumab are fully humanized, monoclonal IgG1 antibody against TNFα, administered subcutaneously. Certolizumab pegol contains the Fab fragment of a humanized antibody against TNFα. In order to increase plasma half-life, the Fab fragment is covalently attached to a polyethylene glycol moiety, which is removed from the antigen-binding site to prevent interference.

2.2. Evidence from Clinical Trials and Open-label Extension Studies

Randomized trials do not show an increased risk of serious infections in patients taking TNFα antagonists for induction and maintenance therapy. In a comprehensive systematic review with pairwise and network meta-analysis (44 RCTs, 14,032 patients) the overall risk of serious infections was low, and similar with TNFα antagonists vs. placebo (odds ratio [OR], 0.90, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.69–1.17).8 Results with individual TNFα antagonists vs. placebo were consistent – infliximab vs. placebo (16 trials, 60/1732 [3.5%] vs. 53/1190 [4.5%]; OR, 0.81 [0.56–1.19]), adalimumab vs. placebo (8 trials, 32/1782 [1.8%] vs. 25/1128 [2.2%]; OR, 0.80 [0.47–1.36]), certolizumab pegol vs. placebo (7 trials, 23/1205 [1.9%] vs. 14/974 [1.4%]; OR, 1.43 [0.74–2.78]) and golimumab vs. placebo (3 trials, 18/1256 [1.4%] vs. 9/564 [1.6%]; OR, 0.93 [0.42–2.05]). In contrast, opportunistic infections are more likely to occur with TNFα antagonists vs. placebo (OR, 1.89 [1.15–3.12]), and this is similar among different TNFα antagonists.8

Open-label extension studies, which selectively include patients responding to treatment of interest, provide insight into the absolute long-term risk of serious and opportunistic infections beyond the 1 year follow-up typical of a randomized trial of maintenance therapy. In up to four years of ADHERE, an open-label extension study of CD patients responsive to adalimumab, serious infections with adalimumab occurred at 6.1 events per 100-PY and opportunistic infections occurred at 1.3 events per 100-PY.9 Overall, the incidence of serious and opportunistic infections remained steady over time indicating no progressive increased risk with prolonged adalimumab treatment. Similar rates of serious infections were observed in open-label extension studies with infliximab followed up to 3 years (ACT-trials of UC, 230 patients; 3.4 per 100-PY)10 and certolizumab pegol followed up to 7 years (PRECiSE 3 trial, 595 patients, 1,920 PY follow-up; 4.4 per 100-PY).11

2.3. Evidence from Clinical Registries

Clinical registries are a valuable resource that provide long-term safety data from clinical practice settings that can be helpful for clarifying the risk of infection and malignancy. These patients are more representative of the general population as compared to those included in clinical trials. To date, the most important findings come from pivotal registries for infliximab and adalimumab.

TREAT Registry (Infliximab, USA):

The TREAT registry consisted of real-world clinical practice data from 6,273 patients (3,440 infliximab-treated and 2,833 other-treatments-only) with up to 13 years of follow-up.12 Overall, serious infections occurred at 2.2 events per 100-PY in infliximab-treated patients compared to 0.9 events per 100-PY in other-treatments-only patients. Pneumonia was the most common serious infection with 47 cases at 0.22 events per 100-PY in infliximab-treated patients (vs. 0.09 events per 100-PY in other-treatments-only patients). Low rates of tuberculosis were reported with 3 cases overall, 2 of which were in patients who received infliximab (0.01 per 100-PY).

ENCORE Registry (Infliximab, Europe):

In Europe, a similar large, prospective, observational registry followed patients in clinical practice settings with CD who were initiated on infliximab and followed for up to 5 years.13 In ENCORE, patients included were naïve to infliximab and received induction therapy upon entering the registry, whereas patients in the TREAT registry were already receiving infliximab infusions. ENCORE consisted of 2,662 total patients including 1,541 patients who received infliximab and 1,121 patients who received conventional therapy. Of those who received conventional therapy, 298 patients (27%) ultimately converted to infliximab, comprising of 3,687 patients with infliximab exposure (7,362 patient-years). Serious infections occurred in 8.6% of patients with infliximab, 6.0% of patients who switched to infliximab and 4.2% of patients with conventional treatment. Patients with infliximab exposure experienced a statistically significant greater incidence of serious infections compared to non-exposure with 2.7 events per 100-PY vs. 1.7 per 100-PY. Overall, the data from ENCORE suggests that infliximab exposure is associated with an increased risk of serious infections compared to other conventional therapies and similarly to the TREAT registry, corticosteroids use is a known predictor of serious infections.

PYRAMID Registry (Adalimumab, USA and Europe):

PYRAMID is a large, multi-center observational registry representing data from patients in clinical practice with moderate to severely active CD who were treated with adalimumab.14 A total of 5,025 patients were followed for up to 6 years (total 16,680.4 PY) after adalimumab exposure across 24 different countries. At the time of enrollment, nearly half of patients were receiving combined immunosuppression with 24% on concomitant immunomodulators, 18% on concomitant corticosteroids and 12% on triple immunosuppression with both immunomodulators and corticosteroids. Overall, registry treatment emergent serious infections were reported at a rate of 4.7 events per 100-PY from 556 patients (11.1%). Opportunistic infections, excluding oral candidiasis and tuberculosis, occurred at a much lower rate at 0.1 events per 100-PY. Out of the serious infections which occurred greater than 0.1 events per 100-PY (6.5%), more than half were gastrointestinal related including abdominal abscess (0.9%), intestinal abscess (0.4%), anal abscess (2.4%), and rectal abscess (0.4%). A higher proportion of patients were found to have registry treatment-emergent serious infections with concomitant immunomodulator use compared to those with adalimumab monotherapy (12.6% vs. 10.2%, P=0.01). When stratifying by baseline corticosteroid use, there was a statistically significant greater proportion of patients with registry treatment-emergent serious infections with concomitant baseline immunomodulators with corticosteroids and without corticosteroids compared to adalimumab monotherapy (12.6% vs. 9.6% P=0.04) and (12.7% vs. 9.6%, P=0.01) respectively.

2.4. Evidence from Real World Observational Studies

Three large administrative claims-based analyses have provided insight into the real-world risk of serious and/or opportunistic infections with TNFα antagonists. In a retrospective French population-based cohort study using the national health insurance database of 85,850 TNFα-antagonist and/or immunosuppressive-treated patients (178,155-PY), allowing for multiple unidirectional exposures per patient, Kirchgesner and colleagues observed that the combination of TNFα antagonist and immunomodulators (thiopurines or methotrexate) is associated with a higher risk of serious infections (requiring hospitalization) (2.2 per 100-PY) as compared to patients treated with TNFα antagonist monotherapy (1.9 per 100-PY) which itself is associated with higher risk of infection as compared to immunomodulator monotherapy (1.1 per 100-PY).15 Corresponding rates of opportunistic infections were 0.41 per 100-PY, 0.21 per 100-PY and 0.17 per 100-PY with combination therapy, TNFα antagonist monotherapy and immunomodulator monotherapy, respectively. After adjusting for important confounders, exposure to combination therapy was associated with higher risk of opportunistic infections as compared to monotherapy with either TNFα antagonist or immunomodulators. However, there was no difference in risk of opportunistic infections with TNFα antagonist monotherapy vs. immunomodulator monotherapy (HR, 1.08 [0.83–1.40]). The most common sites of serious infections were pulmonary (24.2%), gastrointestinal tract (22.5%) and skin (17.2%); the most common cause for opportunistic infections was viral. Approximately 3.9% of patients with serious infections died within 3 months. In a Danish propensity score matched population-based cohort study, Andersen and colleagues estimated that TNFα antagonist-based therapy is associated with 2.1 times higher risk of serious infections within 1 year, as compared to immunomodulator-based therapy.16 In a U.S. multi-database study representing older patients (SABER cohort including Medicaid Analytic Extract linked to Medicare, Tennessee Medicaid, two US states Medicare, Kaiser Permanente), Grijlava and colleagues estimated that rates of serious infections were higher than in other cohorts, but comparable for TNFα antagonist-based therapy and immunomodulator based therapy (10.9 per 100-PY vs. 9.6 per 100-PY).17

On meta-analysis of comparative studies including registries and observational comparative effectiveness studies, we observed that the risk of serious infections was modestly higher with combination therapy of TNFα antagonist and immunomodulators vs. TNFα antagonist monotherapy (6 cohorts, relative risk [RR], 1.19 [1.03–1.37]), and vs. immunomodulator monotherapy (2 cohorts, RR, 1.78 [1.24–2.57]).18 Based on 5 cohorts, we estimated that across studies, the median (range) of serious infections with TNFα antagonist monotherapy and immunomodulator monotherapy was 3.9 (0.4–11.1) and 2.2 (0.9–11.2) per 100-PY, respectively, with corresponding risk of serious infections being 64% higher with TNFα antagonist monotherapy (RR, 1.64 [1.19–2.27]).18 In a single retrospective cohort study among Medicaid and Medicare beneficiaries from 2001 to 2013, Lewis and colleagues compared risk of serious infections in new users of TNFα antagonist vs. patients treated with chronic corticosteroids (>3000 mg prednisone or equivalent) over 12 months.19 There was no difference in the risk of serious infections in patients treated with TNFα antagonists vs. those treated with chronic corticosteroids in patients with CD (6.6 vs. 7.7 per 100-PY; OR, 0.98 [0.87–1.10]) or in patients with UC (4.7 vs. 5.5 per 100-PY; OR, 0.99 [0.78–1.26]).

There is very limited comparative safety data for biologic agents. Based on a meta-analysis of comparative risk of serious infections with infliximab vs. adalimumab, we observed that patients with UC treated with infliximab had a lower risk of serious infections compared with adalimumab (OR 0.57 [0.33–0.97]); however patients with CD had a similar risk of serious infections with infliximab compared to adalimumab (OR 0.91 [0.49–1.70]).18 This may potentially be related to higher efficacy of infliximab vs. adalimumab for UC, which may help maintain corticosteroid-free remission. There is limited comparative safety data for TNFα antagonists vs. other non-TNFα-blocking biologics, agents such as vedolizumab, ustekinumab or tofacitinib. One preliminary multi-center study evaluating patients treated with vedolizumab versus TNFα antagonists, observed lower rates of serious infections in vedolizumab-treated patients (6.9% vs. 10.1%; OR, 0.67 [0.41–1.07]); however this potential safety advantage dissipated with concomitant use of immunomodulators and corticosteroids (11.5% vs. 13.9%; OR 0.81 [0.31–2.07]).20

2.5. Risk Factors for Serious and/or Opportunistic Infections with TNFα antagonists

Several predictors of increased risk of serious infections with TNFα antagonists have been identified. In the TREAT registry of infliximab or conventionally-treated patients with CD, independent predictors of serious infection risk were moderate-severe disease activity at baseline (HR, 2.21 [1.55–3.14]), narcotic use (HR, 1.96 [1.42–2.70]), prednisone use (HR, 1.59 [1.19–2.12]) and infliximab use (HR, 1.45 [1.13–1.86]).12 The dose of infliximab (5mg/kg, 10mg/kg or unknown) and number of cumulative infliximab infusions (2 or greater) did not predict an increased risk for serious infections. Similarly, in the European ENCORE registry, besides prednisone use and infliximab exposure, longer disease duration (≥6 years) was independently associated with increased risk of serious infections (HR, 1.42 [1.09–1.86]).13 Baseline disease severity was not a significant predictor for serious infection risk. In a pooled analysis of 8 randomized trials of adalimumab in CD or the open-label extension study ADHERE (2,266 patients), high baseline disease activity and concomitant use of immunomodulators and/or corticosteroids was associated with increased risk of serious as well as opportunistic infections.3 In another case-control study, Toruner and colleagues reported an increased risk of opportunistic infection with infliximab alone or in combination with immunosuppressive medications.21 However, the risk only achieved statistical significance once triple immunosuppression was used with infliximab, thiopurines and corticosteroids. Besides these, older age may be associated with increased risk of serious infections across all biologic agents, including TNFα antagonists. In a meta-analysis of 14 cohort studies across all immune-mediated inflammatory diseases that comprised 4,719 older users of biologics and 13,305 younger users of biologics, the pooled prevalence of infections in older and younger users of biologics was 13% and 6% respectively (OR, 2.28 [1.57–3.31]).22

3. Non-TNF-targeted Biologic Agents and Targeted Small Molecules

Vedolizumab

Vedolizumab is a fully humanized, monoclonal IgG1 antibody that binds to the α4β7 integrin and blocks lymphocyte interaction with mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 expressed on the endothelium of mesenteric lymph nodes and gastrointestinal mucosa, impairing the migration of gut-homing lymphocytes.23 Recent studies have suggested that vedolizumab may exert it’s clinical effect through additional mechanisms of action. Zeissig and colleagues observed that other than inhibition of T-cell trafficking, vedolizumab’s efficacy might be related to modulation of innate immunity with significant changes in macrophage population and altered expression of pattern recognition receptors.24 By virtue of gut-specificity of the receptor, vedolizumab is presumed to be a safer biologic.

3.1. Evidence from Clinical Trials and Open-label Extension Studies

In the GEMINI trials of vedolizumab for CD and UC, the rates of serious infections with vedolizumab did not significantly differ when compared to placebo.25 In a subsequent open-label extension study including data from four placebo-controlled and two open-label trials of vedolizumab in patients with UC or CD, Colombel and colleagues evaluated the safety of vedolizumab in 2,830 patients (4,811 PY vedolizumab exposure). The exposure-adjusted incidence rates of serious infections were similar for vedolizumab compared to placebo (4.3 vs. 3.8 per 100-PY), with similar rates in patients with UC (2.7 vs. 5.0 per 100-PY) and CD (5.6 vs. 3.0 per 100-PY).26 The most common reported serious infections were clostridial infections (n=15, 0.3 per 100-PY) and gastroenteritis (n=17, 0.4 per 100-PY) which occurred only in patients on vedolizumab. Abscess was the most common serious infection in vedolizumab-treated patients (1.4 per 100-PY) and was more commonly observed, as expected, in patients with CD. Tuberculosis occurred in 4 patients, all of which were in vedolizumab-exposed patients.

In a post-marketing study of the vedolizumab global safety database with an estimated 114,071-PY exposure, 210 patients developed opportunistic infections, with Clostridium difficile infection and cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection being the most common.27 Among the opportunistic infections reported, 104 were considered serious, including 2 events that resulted in death: one patient developed Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in the setting of high-dose, long-term corticosteroid use, and a second patient with steroid-refractory graft-versus-host disease, who was using vedolizumab off-label, developed an unspecified opportunistic infection in addition to an existing CMV infection. Tuberculosis was reported in 7 patients. Among 29 patients with concurrent hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection, no cases of reactivation of viral infection were reported. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a potentially fatal neurological condition caused by reactivation of John Cunningham virus with exposure to another anti-integrin agent, natalizumab, has not been a concern with vedolizumab. To date, if the risk of PML with vedolizumab were hypothetically comparable to natalizumab, 30.2 cases would have occurred.28 Thus far, only one case of PML has been reported in a patient who was also diagnosed with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

3.2. Evidence from Registry Studies

Registry studies of vedolizumab to evaluate long-term safety in the real-world are ongoing.

3.3. Evidence from Real World Observational Studies

In a multi-institutional consortium of 1,087 vedolizumab-treated patients followed for up to 3 years, Meserve and colleagues evaluated the safety of vedolizumab in a real world setting. In this cohort, 38% patients were on concomitant immunomodulators, 49% were on concomitant corticosteroids and 20% were on triple immunosuppression with both immunomodulators and corticosteroids; >90% patients had prior exposure to TNFα antagonists.29 In total, 6.3% of patients developed serious infections (n=68) with Clostridium difficile infection being the most common (n=21), followed by cytomegalovirus colitis (n=4). When expanding the definition of serious infection as applied to other clinical trials, the observed incidence rate during this analysis was 4.5 per 100-PY exposure, which is similar to rates seen in studies with TNFα antagonists.

There has been limited comparative assessment of the safety of vedolizumab vs. TNFα antagonists.

3.4. Risk Factors for Serious and/or Opportunistic Infections with Vedolizumab

In the GEMINI open-label extension studies, independent predictors of serious infections in vedolizumab-treated patients with CD included narcotic use (HR, 2.72 [1.90–3.89]) and corticosteroid use (HR, 1.88 [1.35–2.63]).26 In patients with UC, besides narcotic use, prior failure of TNFα antagonists was a risk factor for serious infections (HR, 1.99 [1.16–3.42]). Baseline disease severity was not identified as an independent predictor of serious infections. In the VICTORY consortium, active smoking (OR, 3.39 [1.71–6.70] and number of concomitant immunosuppressive agents used (OR, 1.72 per agent [1.20–2.46]) were associated with increased risk of serious infection.30 The investigators observed that the incidence of serious infections was comparable in patients treated with vedolizumab monotherapy vs. vedolizumab and immunomodulators (5.2 per 100-PY exposed vs. 5.8 per 100-PY, respectively). However, with the addition of corticosteroids to either vedolizumab monotherapy (9.5 per 100-PY) or vedolizumab and immunomodulators (12 per 100-PY), the risk of serious infections was significantly higher.

Ustekinumab

Ustekinumab is a monoclonal antibody which binds to both interleukin-12 and interleukin-23 with affinity to the p40 subunit. It has demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis31 and is also effective for the induction and maintenance of remission for patients with moderate to severely active Crohn’s disease.32

3.5. Evidence from Clinical Trials and Open-label Extension Studies

Through two years of UNITI trials, with 1,020-PY exposure, the incidence of serious infections with ustekinumab was not different from placebo (4.0 vs. 4.1 per 100-PY).33 Three opportunistic infections occurred including Listeria meningitis (n=1) in a patient on concomitant corticosteroids and esophageal candidiasis (n=2). Long-term open-label data on ustekinumab in CD is currently awaited. In open-label extension studies of ustekinumab in psoriasis (3,117 patients, 8,998-PY of follow-up), Papp and colleagues observed that the rate of serious infections was 0.98 events per 100-PY in patients on 45mg ustekinumab and 1.19 per 100-PY on 90mg ustekinumab every 12 weeks.34

3.6. Evidence from Registry Studies and Real-World Observational Studies

Registry studies and large real-world observational studies of ustekinumab in CD are currently awaited. In the BADBIR registry (British Association of Dermatologists Biologic Interventions Register) of biologic therapies in psoriasis, the incidence rate of serious infections with ustekinumab was 1.5 per 100-PY, and the risk was not higher compared with other non-biologic systemic therapies (HR, 0.92 [0.60–1.41]).35 Similarly, in the BIOBADADERM registry (Spanish Registry of Adverse Events for Biological Therapy in Dermatological Diseases) of moderate-severe plaque psoriasis, ustekinumab alone or in combination with methotrexate was not associated with higher risk of serious infections as compared to methotrexate alone.36 In the U.S. PSOLAR (Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry) registry with 12,093 patients (40,388-PY follow-up), the absolute risk of serious infections with ustekinumab (0.93 per 100-PY) was lower as compared to infliximab (2.91 per 100-PY) and other biologic agents (1.91 per 100-PY).37 These findings on the relative safety of ustekinumab in patients with psoriasis should be interpreted with caution, though, since the dose of ustekinumab approved for use in CD is at least 50% higher than the dose used in psoriasis.

Tofacitinib

Unlike biologic agents, tofacitinib is an orally administered targeted small molecule which inhibits JAK1 and JAK3 tyrosine kinases within the JAK-STAT signaling pathways. In placebo-controlled trials, tofacitinib has been shown to be effective in induction and maintenance of remission in patients with moderately to severely active UC.38

3.7. Evidence from Clinical Trials and Open-label Extension Studies

In OCTAVE-1, −2 and -Sustain trials, the rates of serious infection were overall low. In a trial of maintenance therapy with tofacitinib (OCTAVE Sustain), serious infections occurred in 1% and 0.5% of patients receiving either 5mg or 10mg twice/day tofacitinib, respectively.38 Long-term safety of tofacitinib in patients with UC was described in an integrated, pooled analysis of clinical trials with up to 4.4 years of follow-up.39 The analysis included 3 cohorts defined as induction, maintenance and overall, which included patients receiving 5mg or 10mg twice/day of tofacitinib in clinical trials or open-label extension studies. The overall cohort was comprised of 1,613 PY of tofacitinib exposure with the majority of patients receiving tofacitinib 10mg twice/day. In total, there were 33 cases of serious infections with an incidence rate of 2.0 per 100-PY which is similar for maintenance cohorts. Opportunistic infections occurred in 21 patients and 81.8% of those were related to herpes zoster (incidence rate, 4.1 per 100-PY). In a global open-label extension study of tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis with 4,481 patients followed for up to 9.5 years, incidence rate of serious infections, tuberculosis and non-tuberculosis opportunistic infections was 2.4, 0.2 and 0.5 per 100-PY, respectively.40

One specific infectious concern with tofacitinib has been the risk of herpes zoster. In the maintenance trial of tofacitinib, incidence of herpes zoster was dose-dependent, with higher rates in the 10mg twice/day arm (6.6 per 100-PY) vs. 5mg twice/day arm (2.1 per 100-PY), compared to placebo (1 per 100-PY). Main risk factors associated with herpes zoster were prior failure of TNFα antagonists, older age, and non-Caucasian race, specifically Asian patients. In the global open-label extension study of tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis, incidence of herpes zoster was 3.4 per 100-PY and higher rates were observed at higher doses. However, it is important to note that this increased risk of herpes zoster in patients with IBD is not limited to tofacitinib-treated patients. In a nested case-control cohort of 26,263 patients with IBD (none on tofacitinib) in South Korea using administrative claims data, the incidence rate of herpes zoster was 1.8 per 100-PY, higher than the background rate in the general population (IR, 1.1 per 100-PY; standardized incidence rate, 1.48 [1.42–1.54])41. Corticosteroid use was an independent risk factor for herpes zoster. These findings were replicated in a multicenter database of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, IBD, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and ankylosis spondylitis.17 In this study, there were 33,324 patients newly initiated patients on TNFα antagonists, and 310 patients developed herpes zoster. Higher doses of corticosteroids (mean daily dose of ≥10mg) was associated with an increased risk of herpes zoster across all disease indications (HR, 2.13 [1.64,2.75]). In a retrospective cohort study of patients with IBD using the Veterans Administration database, Khan and colleagues observed higher rates of herpes zoster with exposure to thiopurines as compared to patients treated with 5-aminosalicylates (HR, 1.47 [1.31–1.65]), and combination of thiopurines and TNFα antagonists (HR, 1.65 [1.22–2.23]), though this risk was not increased with TNFα antagonist monotherapy (HR, 1.15 [0.96–1.38]).42

3.8. Evidence from Registry Studies and Real-World Observational Studies

Registry studies and large real-world observational studies of tofacitinib in UC are currently awaited. In the US CORRONA registry for rheumatoid arthritis, over a 5-year period, comparative incidence of serious infections with tofacitinib (1,492 patients, with 1,925-PY follow-up) and other biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (6,881 patients, with 8.567-PY follow-up) was 3.51 per 100-PY vs. 3.29 per 100-PY.43 These findings should be extrapolated with caution to UC, since in rheumatoid arthritis, lower doses of tofacitinib are used for maintenance therapy (5mg twice/day). In contrast, higher doses (10mg twice/day) are recommended in patients with UC with prior exposure to TNFα antagonists.

4. MALIGNANCY

Tumor necrosis factor-α antagonists

4.1. Evidence from Clinical Trials and Open-label Extension Studies

In a comprehensive systematic review including 23 RCTs of TNFα antagonists in IBD, with at least one reported cancer, there was no significant increase in risk of malignancy with TNFα antagonists (20/4,442) vs. placebo (16/2,778). Similarly, in a pooled analysis of patients who participated in clinical trials and open-label extension studies of adalimumab in CD (1,594 patients, 3,050-PY exposed), as compared to U.S. Surveillance and Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database, there was no increase in the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) (SIR, 1.2 [0.39–2.80]) or malignancy excluding NMSC (SIR, 0.63 [0.17–1.62]) with adalimumab monotherapy.44 However, the addition of immunomodulators to adalimumab therapy led to a 4.6 times greater risk of developing NMSC (SIR, 4.59 [2.51–7.70]) and 3 times greater risk of developing a malignancy excluding NMSC (SIR, 3.04 [1.66–5.10]), as compared the US SEER population. An increased risk of malignancy remained evident in patients on combination therapy when compared to those treated with adalimumab monotherapy, with a 3.5 times greater risk of NMSC (RR, 3.46 [1.08–11.06]) and 2.8 times greater risk of malignancy other than NMSC (RR, 2.82 [1.07–7.44]).

4.2. Evidence from Registry Studies

In the TREAT registry of 6,273 patients with CD (3,420 treated with infliximab, 3,764 treated with conventional therapy, average follow-up 5.2 years), incidence of malignancy in infliximab-treated patients was 0.64 per 100-PY, which was not significantly different than the rate with conventional therapy (RR, 0.88 [0.66–1.19]).12 Specifically, the risk of lymphoma was 0.05 per 100-PY in infliximab-treated patients (RR vs. conventional treatment, 0.98 [0.34–2.82]). On multivariable analysis, advanced age, longer disease duration and smoking were independently associated with increased risk of malignancy, whereas exposure to infliximab and/or immunosuppressive therapy was not associated with increased risk of malignancy. Similarly, in the PYRAMID registry of 5,025 patients with CD treated with adalimumab with mean follow-up of ~3 years, the incidence of any malignancy (including NMSC) was 0.8 per 100-PY. There were 10 cases of lymphoma in the registry, with a rate lower than the estimated background lymphoma rate (0.084 E per 100-PY) and similar to the rate observed for infliximab from the TREAT registry. Risk of malignancy was higher in patients concomitantly on thiopurines vs. adalimumab monotherapy (3.1% vs. 1.9%, p=0.01).

4.3. Evidence from Real-World Observational Studies

In a Danish nationwide registry-based cohort study of 56,146 patients with IBD followed over a median of 9.3 years, the incidence rate of malignancy in 4,553 patients exposed to TNFα antagonists was 0.43 per 100-PY.45 In a fully adjusted model, including age, calendar year, disease duration, baseline propensity scores, use of 5-aminosalicylates, local and systemic corticosteroids, and immunosuppressive agents, the overall risk of cancer was not different in patients exposed vs. unexposed to TNFα antagonists (RR, 1.07 [0.85–1.36]). There was no significant effect of age at time of exposure, and cumulative dose/duration of exposure, on overall risk of cancer. Specifically, TNFα antagonist exposure was not associated with increased risk of melanoma or lymphoma. In a French population-based cohort using the National Health Insurance databases of 189,289 patients followed over a median 6.7 years, Lemaitre and colleagues identified 336 cases of lymphoma.46 Incidence rate (per 100-PY) of lymphoma in unexposed patients, patients exposed to thiopurine monotherapy, to TNFα antagonist monotherapy and to combination therapy was 0.026 (0.023–0.029), 0.054 (0.041–0.067), 0.041 (0.027–0.055), and 0.095 (0.045–0.145), respectively. In a multivariable Cox model, compared with unexposed patients, the risk of lymphoma was higher among those exposed to thiopurine monotherapy (HR, 2.60 [1.96–3.44]), TNFα antagonist monotherapy (HR, 2.41 [1.60–3.64]) and combination therapy (HR, 6.11 [3.46–10.8]). The risk was higher in patients exposed to combination therapy vs. those exposed to thiopurine monotherapy (HR, 2.35 [1.31–4.22]) or TNFα antagonist monotherapy (HR, 2.53 [1.35–4.77]). In a multicenter, nested case-control study, Biancone and colleagues observed that penetrating disease (OR, 2.33 [1.10–5.47]) and combination therapy of TNFα antagonists and thiopurines (OR, 1.97 [1.1–3.5]) were independently associated with overall risk of cancer in patients with CD, whereas pancolitis (OR, 2.52 [1.26–5.1]) and IBD-related surgery (OR, 5.09 [1.73–17.1]) were associated with increased risk of cancer in patients with UC.47

There is conflicting evidence whether TNFα antagonists may be associated with increased risk of melanoma. In a meta-analysis of 12 observational studies, Singh and colleagues observed that IBD was associated with an increased risk of melanoma.48 Long and colleagues observed that exposure to TNFα antagonists may be associated with a 1.9-fold increase in risk of melanoma.49 However, in the French CESAME cohort, impact of TNFα antagonists on the risk of melanoma was not apparent, although a very small subset of patients were exposed to biologic agents.50

5. Non-TNF-targeted Biologic Agents and Targeted Small Molecules

Vedolizumab

5.1. Evidence from Clinical Trials and Open-label Extension Studies

In an open-label extension study including data from four placebo-controlled and two open-label trials of vedolizumab in patients with IBD, Colombel and colleagues reported malignancy in 18/2,830 (0.6%) patients treated with vedolizumab and 1/504 (0.2%) placebo-treated patients.26 Of the 18 patients with malignancies, most common were gastrointestinal (n=6, 3 colorectal cancers, 1 hepatic cancer, 1 appendiceal carcinoid and 1 peritoneal metastases), followed by dermatological malignancies (n=5, 2 melanomas, 2 squamous and 1 basal cell carcinoma). Gastrointestinal malignancies were diagnosed after an average 11.8y history of IBD and a median of 8 (range 2‐41) vedolizumab infusions. All patients had previously received thiopurines and at least one other biologic. Of the 12 non-gastrointestinal malignancies, 11 patients had received a thiopurine and 9 a biologic agent. On an updated analysis of this long-term safety study with 7,746-PY follow-up, standardized incidence rate of malignancy was 0.50 (0.34–0.71), when compared to an age- and sex-adjusted Optum’s Clinformatics Data Mart database. Post-marketing surveillance reported 299 malignancies in 293 patients with 208,050-PY vedolizumab exposure, though this must be interpreted with caution due to reliance on voluntary reporting.

5.2. Evidence from Registry Studies and Real-World Observational Studies

There is paucity of registry studies of vedolizumab to evaluate long-term risk of malignancy. In the multi-institutional VICTORY consortium, two patients developed malignancies with an incidence rate of 0.23 per 100-PY. One patient who developed squamous cell cancer of the hand had a history of long-standing UC pancolitis, with prior TNFα antagonist exposure and concomitant two-year azathioprine exposure. The other patient who developed colon cancer also had a history of UC pancolitis (>9 years) with prior azathioprine and TNFα antagonist exposure. There were no reported lymphomas.

Ustekinumab

5.3. Evidence from Clinical Trials and Open-label Extension Studies

In phase III trials of CD with 1 year of follow-up, incidence of NMSC and solid organ cancers in ustekinumab-treated patients was 0.4 and 0.3 per 100-PY, respectively. In an integrated safety analyses of phase II/III trials of ustekinumab for psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and CD, the incidence of malignancy (excluding NMSC) was low and comparable among ustekinumab-treated patients (0.4 per 100-PY) and placebo-treated patients (0.2 per 100-PY).51 Combined across indications, the standardized incidence rate for malignancies (excluding cervical cancer in situ and NMSC per SEER) in the ustekinumab and placebo groups were 0.6 (0.3–1.0) and 0.3 (0.0–1.9), respectively, with overlapping 95% CIs.

5.4. Evidence from Registry Studies and Real-World Observational Studies

Registry studies and large real-world observational studies of ustekinumab in CD are not yet available. In psoriasis, in nested case-control analysis of PSOLAR registry (Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry) of 12,090 patients, 252 patients with malignancy were matched with 1,008 patients without malignancy. In this analysis, treatment with ustekinumab for 0–3 months, 3–12 months or >12 months was not associated with increased odds of malignancy versus no exposure; in contrast, in this registry, longer-term (≥12 months) exposure to TNFα antagonist was associated with increased odds of malignancy (OR, 1.54 [1.10–2.15]).52 In a post-marketing surveillance study relying on voluntary reporting using FAERS (U.S. Food and Drug Administration FDA Adverse Event Reporting System) and EudraVigilance (European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Pharmacovigilance) in the European Union for ustekinumab for psoriasis, a safety signal was detected for B‐cell lymphoma (n=14), epithelioid sarcoma (n=5) and other solid organ cancers: lung (n=21), esophageal (n=5), ovarian (n=10), renal (n=6), testis (n=6) and thyroid (n=20).53

Tofacitinib

5.5. Evidence from Clinical Trials and Open-label Extension Studies

In a pooled analysis of phase 2, phase 3, or open-label, long-term extension studies of tofacitinib in UC (n=1,157; 1,613 patient-years’ exposure, up to 4.4 years of follow-up), the incidence of malignancy (excluding NMSC) and NMSC was 0.7 (0.3–1.2), and 0.7 (0.3–1.2), respectively.39 There was no pattern in the types of malignancy observed, with 1 case reported for each of the following cancers: cervical cancer, hepatic angiosarcoma, cholangiocarcinoma, cutaneous leiomyosarcoma, Epstein-Barr-virus-associated lymphoma, renal cell carcinoma, essential thrombocythemia, acute myeloid leukemia, adenocarcinoma of colon, lung cancer, and breast cancer. In 11 patients who developed NMSC, advanced age and prior failure of TNFα antagonist were associated with increased risk.

Extrapolating from trials and long-term extension studies of tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis, of 5,677 adult patients, 107 patients developed malignancies (excluding NMSC); most common cancers were lung cancer (n=24) and breast cancer (n=19), with 10 patients developing lymphomas. Compared to age- and sex-matched population from SEER database, there was no significant increase in risk of malignancy with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis (standardized incidence rate, 1.17 [0.96, 1.41]). In a global open-label extension study of tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis with 4,481 patients followed for up to 9.5 years, the incidence rate of malignancy (excluding NMSC) was 0.8 (0.7–1.0) per 100-PY, with 9 cases of lymphoma and 13 cases of melanoma; incidence rate of NMSC was 0.7 (0.6–0.9) per 100-PY.40

5.6. Evidence from Registry Studies and Real-World Observational Studies

Registry studies and large real-world observational studies of tofacitinib in UC are not yet available. In the US CORRONA registry for rheumatoid arthritis, incidence of malignancy in tofacitinib-treated patients was 2.52 per 100-PY vs. 1.83 in patients treated with other biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs.43 These findings should be extrapolated with caution to UC, since in rheumatoid arthritis, lower doses of tofacitinib are used for maintenance therapy (5mg twice/day), in contrast to higher doses (10mg twice/day) recommended in patients with UC with prior exposure to TNFα antagonists.

6. Expert Opinion

Serious Infections:

Currently approved biologic medications including TNFα antagonists, vedolizumab, ustekinumab, as well as targeted small molecules like tofacitinib may be associated with an increased risk of serious infections. The most robust estimates from registries and real-world observational studies are available for TNFα antagonists, which may be associated with 1.5–2 times higher risk of serious infections as compared to non-biologic immunosuppressive agents like thiopurines or methotrexate. In contrast, there is limited real-world observational or registry data for vedolizumab or ustekinumab, although extrapolating from open-label extension studies and other autoimmune diseases like psoriasis, the risk of serious infections with monotherapy with these agents may be lower as compared to TNFα antagonist monotherapy. Most consistent risk factors for serious infections include use of combination therapy with immunosuppressive agents and/or corticosteroids, moderate to severe disease activity, and older age. Table 1 synthesizes the incidence rate of serious infections across different pharmacotherapies.

Table 1.

Incidence rate of serious infections and malignancy (per 100-PY) in patients with moderate to severe IBD treated with pharmacotherapy [Abbreviations: SI-serious infections; TNFα-Tumor necrosis factorα]

| Drug Class | Clinical Trials & Open Label Extensions (per 100-PY) | Safety Registries (per 100-PY) | Real-World Observational Studies (per 100-PY) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNFα antagonists | SI: 3.4-6.1 Malignancy: 0.45 |

SI: 2.2-4.7 Malignancy: 0.64-0.8 |

SI: 1.9-10.9 Malignancy: 0.43 (lymphoma, 0.04) |

| Vedolizumab | SI: 4.3 Malignancy: 0.50 |

- | SI: 5.2 Malignancy: 0.23 |

| Ustekinumab | SI: 4.0 Malignancy: 0.4 |

- (SI: 0.9-1.5 in psoriasis) |

- |

| Tofacitinib | SI: 2.0 Malignancy: 0.7 |

- (SI: 3.5 in rheumatoid arthritis; malignancy: 2.5) |

- |

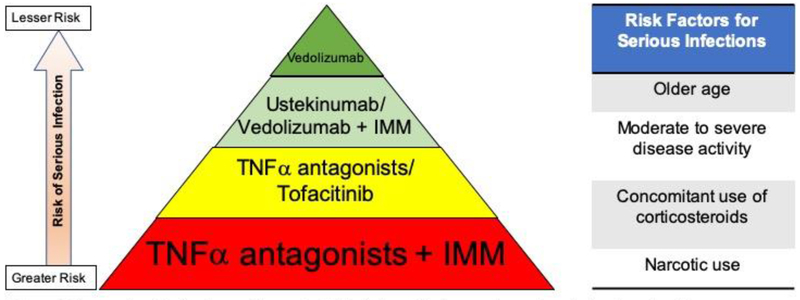

Overall, TNFα antagonists may be more immunosuppressive than others, especially gut-selective vedolizumab, and may potentially increase the risk of systemic infections. However, comparative safety of pharmacotherapy for IBD should be viewed in conjunction with efficacy and in the context of treatment strategies/approach, rather than in the context of specific agents used. Even though a specific agent may be safer in isolation, if it has lower efficacy as compared to another intervention, patients may fail to achieve remission, leading to ongoing severe inflammation necessitating corticosteroids, and eventually leading to higher risk of serious infections. Figure 1 summarizes our interpretation of the comparative safety and risk factors associated with risk of serious infections in patients with IBD.

Figure 1.

Comparative risk of serious and/or opportunistic infections with pharmacotherapy in patients with moderate to severe IBD [Abbreviations: IMM-Immunomodulators; TNFα-Tumor necrosis factorα]

Malignancy:

Among currently approved biologic medications, TNFα antagonists may be associated with an increased risk of lymphoma, particularly when used in combination with thiopurines. There is no evidence of increased risk of other cancers. There is limited data on the risk of malignancy with newer non-TNF-targeting biologics including vedolizumab and ustekinumab or targeted small molecules such as tofacitinib, in patients with IBD. Extrapolating from risks in other immune-mediated diseases, ustekinumab may not be associated with increased risk of malignancy, and risk associated with tofacitinib is currently unclear.

Future studies:

Well-designed comparative real-world studies are warranted to optimally inform risks associated with newer non-TNF-targeting biologics, especially over longer-term horizons which are not captured within the confines of clinical trials. While awaiting such studies, patients at high risk of disease-related complications ought to be treated aggressively as appropriate with combination therapy, rather than conservatively due to fear of serious infections. In contrast, patients at high risk of treatment-related complications such as serious infections and low risk of disease-related complications should be treated cautiously weighing risk and benefit of therapy.

Article Highlights.

Currently approved biologic medications including TNFα antagonists, vedolizumab, ustekinumab, as well as targeted small molecules like tofacitinib may be associated with an increased risk of serious infections. Risk of serious infections may be higher with TNFα antagonists than others, especially gut-selective vedolizumab.

Most consistent risk factors for serious infections include use of combination therapy with immunosuppressive agents and/or corticosteroids, moderate to severe disease activity, and older age.

TNFα antagonists may also be associated with an increased risk of lymphoma, particularly when used in combination with thiopurines. There is limited data on the risk of malignancy with newer non-TNF-targeting biologics including vedolizumab and ustekinumab or targeted small molecules such as tofacitinib, in patients with IBD.

Comparative safety of pharmacotherapy for IBD should be viewed in conjunction with efficacy and in the context of treatment strategies/approach, rather than in the context of specific agents used.

Well-designed comparative real-world studies are warranted to optimally inform risks associated with newer non-TNF-targeting biologics, especially over longer-term horizons which are not captured within the confines of clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases K23DK117058 to Siddharth Singh. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

S Singh has been supported by the NIDDK K23DK117058, the American College of Gastroenterology Junior Faculty Development Award and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation Career Development Award (#404614). Research grant support from AbbVie; Consulting fees from AbbVie, Takeda, AMAG Pharmaceuticals; Honorarium from Pfizer for grant review. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

REFERENCES

Papers of special note have been highlighted as of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1.Nguyen NH, Khera R, Ohno-Machado L, et al. Annual Burden and Costs of Hospitalization for High-Need, High-Cost Patients With Chronic Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:1284–1292.e30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, et al. Serious infection and mortality in patients with Crohn’s disease: more than 5 years of follow-up in the TREATTM registry. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1409–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** Pivotal registry study on the safety of infliximab in Crohn’s disease

- 3.Osterman MT, Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF, et al. Crohn’s Disease Activity and Concomitant Immunosuppressants Affect the Risk of Serious and Opportunistic Infections in Patients Treated With Adalimumab. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:1806–1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Targownik LE, Bernstein CN. Infectious and malignant complications of TNF inhibitor therapy in IBD. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:1835–42, quiz 1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hindryckx P, Novak G, Bonovas S, et al. Infection Risk With Biologic Therapy in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2017;102:633–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abraham C, Cho JH. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2066–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nielsen OH, Ainsworth MA. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors for inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med 2013;369:754–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonovas S, Fiorino G, Allocca M, et al. Biologic Therapies and Risk of Infection and Malignancy in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:1385–1397.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panaccione R, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, et al. Adalimumab maintains remission of Crohn’s disease after up to 4 years of treatment: data from CHARM and ADHERE. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;38:1236–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reinisch W, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, et al. Long-term infliximab maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis: the ACT-1 and −2 extension studies. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012;18:201–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandborn WJ, Lee SD, Randall C, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of certolizumab pegol in the treatment of Crohn’s disease: 7-year results from the PRECiSE 3 study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;40:903–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, et al. Infliximab for Crohn’s Disease: More Than 13 Years of Real-world Experience. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018;24:490–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D’Haens G, Reinisch W, Colombel JF, et al. Five-year Safety Data From ENCORE, a European Observational Safety Registry for Adults With Crohn’s Disease Treated With Infliximab [Remicade(R)] or Conventional Therapy. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:680–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Haens G, Reinisch W, Panaccione R, et al. Lymphoma Risk and Overall Safety Profile of Adalimumab in Patients With Crohn’s Disease With up to 6 Years of Follow-Up in the Pyramid Registry. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:872–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** Pivotal long-term registry study on the safety of adalimumab in patients with Crohn’s disease

- 15.Kirchgesner J, Lemaitre M, Carrat F, et al. Risk of Serious and Opportunistic Infections Associated With Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology 2018;155:337–346 e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** One of the largest population-based studies on the comparative risk of serious infections with biologic and immunosuppressive therapy in IBD

- 16.Nyboe Andersen N, Pasternak B, Friis-Moller N, et al. Association between tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors and risk of serious infections in people with inflammatory bowel disease: nationwide Danish cohort study. BMJ 2015;350:h2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grijalva CG, Chen L, Delzell E, et al. Initiation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists and the risk of hospitalization for infection in patients with autoimmune diseases. JAMA 2011;306:2331–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh S, Facciorusso A, Dulai PS, et al. Comparative Risk of Serious Infections With Biologic and/or Immunosuppressive Therapy in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.02.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** Systematic synthesis of comparative safety data of different therapies for IBD

- 19.Lewis JD, Scott FI, Brensinger CM, et al. Increased Mortality Rates With Prolonged Corticosteroid Therapy When Compared With Antitumor Necrosis Factor-alpha-Directed Therapy for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2018;113:405–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lukin DJ, Weiss A, Aniwan S, et al. Comparative Safety Profile of Vedolizumab and Tumor Necrosis Factor-Antagonist Therapy for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Multicenter Consortium Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Gastroenterology 2018;154:S-68. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toruner M, Loftus EV Jr., Harmsen WS, et al. Risk factors for opportunistic infections in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2008;134:929–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borren NZ, Ananthakrishnan AN. Safety of Biologic Therapy in Older Patients With Immune-Mediated Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosario M, Dirks NL, Milch C, et al. A Review of the Clinical Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Immunogenicity of Vedolizumab. Clin Pharmacokinet 2017;56:1287–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeissig S, Rosati E, Dowds CM, et al. Vedolizumab is associated with changes in innate rather than adaptive immunity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2019;68:25–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2013;369:699–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colombel JF, Sands BE, Rutgeerts P, et al. The safety of vedolizumab for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gut 2017;66:839–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** Safety data from pivotal trials of vedolizumab in IBD

- 27.Ng SC, Hilmi IN, Blake A, et al. Low Frequency of Opportunistic Infections in Patients Receiving Vedolizumab in Clinical Trials and Post-Marketing Setting. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018;24:2431–2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Card T, Xu J, Liang H, et al. What Is the Risk of Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis or Crohn’s Disease Treated With Vedolizumab? Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018;24:953–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meserve J, Aniwan S, Koliani-Pace JL, et al. Retrospective Analysis of Safety of Vedolizumab in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:1533–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dulai PS, Singh S, Jiang X, et al. The Real-World Effectiveness and Safety of Vedolizumab for Moderate-Severe Crohn’s Disease: Results From the US VICTORY Consortium. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:1147–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krueger GG, Langley RG, Leonardi C, et al. A human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody for the treatment of psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2007;356:580–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Gasink C, et al. Ustekinumab as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Crohn’s Disease. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1946–1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Gasink C, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of ustekinumab for Crohn’s disease through the second year of therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;48:65–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Papp KA, Griffiths CE, Gordon K, et al. Long-term safety of ustekinumab in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: final results from 5 years of follow-up. Br J Dermatol 2013;168:844–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yiu ZZN, Smith CH, Ashcroft DM, et al. Risk of Serious Infection in Patients with Psoriasis Receiving Biologic Therapies: A Prospective Cohort Study from the British Association of Dermatologists Biologic Interventions Register (BADBIR). J Invest Dermatol 2018;138:534–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davila-Seijo P, Dauden E, Descalzo MA, et al. Infections in Moderate to Severe Psoriasis Patients Treated with Biological Drugs Compared to Classic Systemic Drugs: Findings from the BIOBADADERM Registry. J Invest Dermatol 2017;137:313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Papp K, Gottlieb AB, Naldi L, et al. Safety Surveillance for Ustekinumab and Other Psoriasis Treatments From the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). J Drugs Dermatol 2015;14:706–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sandborn WJ, Su C, Sands BE, et al. Tofacitinib as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1723–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandborn WJ, Panes J, D’Haens GR, et al. Safety of Tofacitinib for Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis, Based on 4.4 Years of Data From Global Clinical Trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:1541–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wollenhaupt J, Lee EB, Curtis JR, et al. Safety and efficacy of tofacitinib for up to 9.5 years in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: final results of a global, open-label, long-term extension study. Arthritis Res Ther 2019;21:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang K, Lee HS, Kim YJ, et al. Increased Risk of Herpes Zoster Infection in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in Korea. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:1928–1936 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khan N, Patel D, Trivedi C, et al. Overall and Comparative Risk of Herpes Zoster With Pharmacotherapy for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:1919–1927 e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kremer J CL, Etzel CJ, Greenberg J, Geier J, Madsen A, Chen G, Onofrei A, Barr CJ, Pappas DA, Dandreo KJ, Shapiro A, Connell CA, Kavanaugh A. Real-World Data from a Post-Approval Safety Surveillance Study of Tofacitinib Vs Biologic Dmards and Conventional Synthetic Dmards: Five-Year Results from a US-Based Rheumatoid Arthritis Registry. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018;70:A1542. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Osterman MT, Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF, et al. Increased risk of malignancy with adalimumab combination therapy, compared with monotherapy, for Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2014;146:941–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nyboe Andersen N, Pasternak B, Basit S, et al. Association between tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists and risk of cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. JAMA 2014;311:2406–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** Nationwide register-based study on risk of all cancers with TNFα antagonists in IBD

- 46.Lemaitre M, Kirchgesner J, Rudnichi A, et al. Association Between Use of Thiopurines or Tumor Necrosis Factor Antagonists Alone or in Combination and Risk of Lymphoma in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. JAMA 2017;318:1679–1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** French population-based study on the comparative risk of lymphoma in patients treated with thiopurines and/or TNFα antagonists.

- 47.Biancone L, Armuzzi A, Scribano ML, et al. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Phenotype as Risk Factor for Cancer in a Prospective Multicentre Nested Case-Control IG-IBD Study. J Crohns Colitis 2016;10:913–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singh S, Nagpal SJ, Murad MH, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease is associated with an increased risk of melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:210–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Long MD, Martin CF, Pipkin CA, et al. Risk of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2012;143:390–399 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Chevaux JB, Bouvier AM, et al. Risk of melanoma in patients who receive thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease is not increased. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1443–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ghosh S, Gensler LS, Yang Z, et al. Ustekinumab Safety in Psoriasis, Psoriatic Arthritis, and Crohn’s Disease: An Integrated Analysis of Phase II/III Clinical Development Programs. Drug Saf 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fiorentino D, Ho V, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of malignancy with systemic psoriasis treatment in the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment Registry. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;77:845–854.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Florek AG, Nardone B, Thareja S, et al. Malignancies and ustekinumab: an analysis of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System and the European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Pharmacovigilance database. Br J Dermatol 2017;177:e220–e221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]