Abstract

Bronchoscopy enables many minimally invasive chest procedures for diseases such as lung cancer and asthma. Guided by the bronchoscope’s video stream, a physician can navigate the complex three-dimensional (3-D) airway tree to collect tissue samples or administer a disease treatment. Unfortunately, physicians currently discard procedural video because of the overwhelming amount of data generated. Hence, they must rely on memory and anecdotal snapshots to document a procedure. We propose a robust automatic method for summarizing an endobronchial video stream. Inspired by the multimedia concept of the video summary and by research in other endoscopy domains, our method consists of three main steps: 1) shot segmentation, 2) motion analysis, and 3) keyframe selection. Overall, the method derives a true hierarchical decomposition, consisting of a shot set and constituent keyframe set, for a given procedural video. No other method to our knowledge gives such a structured summary for the raw, unscripted, unedited videos arising in endoscopy. Results show that our method more efficiently covers the observed endobronchial regions than other keyframe-selection approaches and is robust to parameter variations. Over a wide range of video sequences, our method required on average only 6.5% of available video frames to achieve a video coverage = 92.7%. We also demonstrate how the derived video summary facilitates direct fusion with a patient’s 3-D chest computed-tomography scan in a system under development, thereby enabling efficient video browsing and retrieval through the complex airway tree.

Keywords: Bronchoscopy, keyframe extraction, lung cancer, video analysis, video summarization and abstraction

I. Introduction

BRONCHOSCOPY enables a number of chest procedures for diseases such as lung cancer and asthma [1]. Using the bronchoscope’s video stream as a guide, a physician can navigate the complex 3D airway tree spanning the two lungs to examine general airway health, collect tissue samples, or administer a disease treatment. The bronchoscope’s light source illuminates the airways, while an embedded camera collects video frames of the illuminated airway endoluminal surfaces. The video stream offers detailed textural and structural information on the endoluminal mucosal surfaces, as well as a record of anatomical locations visited during bronchoscopy.

Unfortunately, while a physician uses the bronchoscopic video to mentally ascertain his/her location within the airway tree, current practice dictates discarding the procedural video because of the overwhelming amount of data generated. For example, a 13-minute 23,000-frame video stream of an airway exam performed using an Olympus BF-180 high-definition (1920 × 1080) bronchovideoscope generates 1.5 gigabits per sec and demands over 18 GB of storage. Manual physician review and annotation of such large videos is extremely impractical. As in related endoscopy domains, such as arthroscopy, laparoscopy, cystoscopy, and colonoscopy, the lack of robust methods for summarizing bronchoscopic video prevents full utilization of this rich data source [2]–[6].

In the general field of multimedia, researchers have proposed a hierarchical approach for parsing a video into successively smaller semantic units [7]–[12]. The motivation for this parsing is to give a top-down summary of a full video’s content and to enable efficient video browsing and retrieval [9]–[11]. Starting with the full video stream, these semantic units include: 1) scenes, consisting of temporally connected shots anchored about a common theme; 2) shots, made up of a continuous subset of video frames focused on a slowly changing or fixed position or action; and 3) keyframes, which are video frames representative of salient content in shots.

The process of parsing video sequence V into a shot set Ψ and identifying a suitable keyframe set Φ is referred to as video summarization (or abstraction) [10], [11]. Scripted media, such as movies and television programs, consist of a series of planned scenes, and, hence, can be relatively straightforward to parse into semantic units. To this point, because scripted media typically contains significantly different content from scene to scene, they lend themselves to intuitive automatic groupings based on simple discriminative features (e.g., dominant color and/or motion) [9], [11]. Even some unscripted multimedia, such as sporting events, often have simplifying features that enable straightforward parsing. Indeed, the problem of shot segmentation in multimedia is generally considered solved as a result of consistently high-accuracy performance on the large dataset from the NIST TRECVID benchmark [9], [10], [13].

Other unscripted media such as surveillance footage, however, prove much more problematic to parse [9]. Endoscopic video certainly qualifies as a problematic video source. Endoscopic video is a continuous, unscripted, unedited source exhibiting considerable redundancy and less obvious breaks between possible shots [5]. To make matters worse, unexpected events are a fundamental part of surgery, resulting in a significant amount of corrupted uninformative data [3], [4], [14]. As an example, bronchoscopic video consists of a continuous stream of comparatively homogeneous video throughout the airway tree with nearly constant color content, interleaved with unpredictable interruptions such as coughing, bleeding, and mucus. As such, the problem of parsing an endoscopic video into a hierarchical summary remains largely open.

Recent research has made inroads into condensing unedited endoscopic video into a more manageable subset. In one body of research, methods for detecting uninformative frames have been incorporated for one of two purposes: a.) to enable more efficient user interaction of recorded endoscopic procedures [3], [4], [15], [16]; and b.) to help localize significant surgical events and diagnostic sites (e.g., intestinal contractions, colonic polyps) [17], [18]. For example, Oh et al. used motion analysis, based MPEG-encoded motion vectors, to segment distinct shots in colonoscopy video [16]. While these commendable works noted upwards of 50% rejection of uninformative frames, their overarching goal was not focused on constructing a summary of a video or reducing redundant frames.

On another front, a second body of research proposed methods that reduced redundant frames by identifying information-rich keyframes for two distinct tasks: a.) to facilitate 3D reconstruction of anatomic surfaces observed during an endoscopy [19]–[21]; and b.) to provide a summary of an endoscopic video [2], [5], [22]. As examples of these works, Soper et al. used SIFT video-frame features and homography-based frame matching in cystoscopic video to arrive at a keyframe set suitable for 3D reconstruction of the bladder surface, while Brischwein et al. employed a similar approach drawing upon SURF features [19], [20]. In addition, Primus et al. proposed Lucas-Kanade feature-based motion tracking, which was later superseded by this group’s effort using an ORB-based feature-analysis method, for keyframe selection [5], [22]. While these researchers noted cutting > 80% of available frames from a typical endoscopic video, they did not strive to parse a video into a hierarchical summary of shots and keyframes [19], [20].

We propose an automatic method for parsing an endobronchial video stream. Inspired by the multimedia concept of the video summary and by research in other endoscopy domains, our method consists of three main steps: 1) shot segmentation, to perform a preliminary grouping of informative frames into shots; 2) motion analysis, to ascertain the local motion between frames constituting individual shots; and 3) keyframe selection, to identify a final keyframe set that adequately summarizes the video’s observed visual content.

Overall, the method produces a true video summary of V, consisting of a hierarchical structure made up of a shot set Ψ and constituent keyframe set Φ. To the best of our knowledge, no previous method gives such a structured summary for the unscripted, unedited videos arising in endoscopy.

The method introduces four enhancements over previously proposed approaches in endoscopy. First, video summarization is cast as an optimization problem that focuses on minimizing the redundancy between keyframes used to represent a video V. Second, shot segmentation includes a novel two-stage procedure incorporating frame matching and shot assembly. While shot segmentation is straightforward for scripted video, such as television, unscripted endoscopic video, often corrupted by uninformative frames and interruptions, requires more effort [4], [15], [18]. Our five-step frame-matching process draws upon two complementary geometric models enabling greater matching discrimination, while shot assembly aggregates informative frames into shots.

As a third enhancement, motion analysis combines measures for intra-frame motion distribution, along with inter-frame measures of aggregate motion direction and energy, to provide more robust motion computation. Finally, keyframe selection adds the notion of a homography-based content-change function to reduce keyframe redundancy, while also enforcing sufficiently unique inter-frame visual content.

Results indicate that the method potentially offers higher video coverage using fewer keyframes than existing keyframe-selection methods. In addition, given the challenge posed by the airway tree, the video summary’s hierarchical decomposition appears to be especially suited to bronchoscopy. To this point, we demonstrate how the video summary facilitates direct linkage and fusion to the airway structure depicted in a corresponding 3D chest computed-tomography (CT) scan. This readily facilitates systematic video browsing and retrieval through the complex branching airways.

Section II describes our method and discusses implementation considerations. Section III next demonstrates method performance, using bronchoscopic video sequences derived from lung-cancer patients. It also illustrates the method’s utility in an interactive bronchoscopic video-analysis system under development [23], [24]. Finally, Section IV offers concluding comments and suggestions for future work.

II. Methods

A. Problem Statement

During bronchoscopy, an endobronchial video sequence

| (1) |

is produced at a rate of 30 frames per sec along the airway-tree trajectory (Fig. 1)

denotes the kth video frame of the sequence produced at bronchoscope pose

| (2) |

To relate the global 3D airway-tree structure to the bronchoscope camera’s observations along Θ, we employ a fixed global coordinate system (X, Y, Z) relative to the patient’s chest and a local coordinate system (x, y, z) relative to the bronchoscope camera. Regarding (2), (α, β, γ) specify the bronchoscope camera’s 3D orientation, while (tX, ty, tz) specify the camera’s spatial location within the global coordinate system [25].

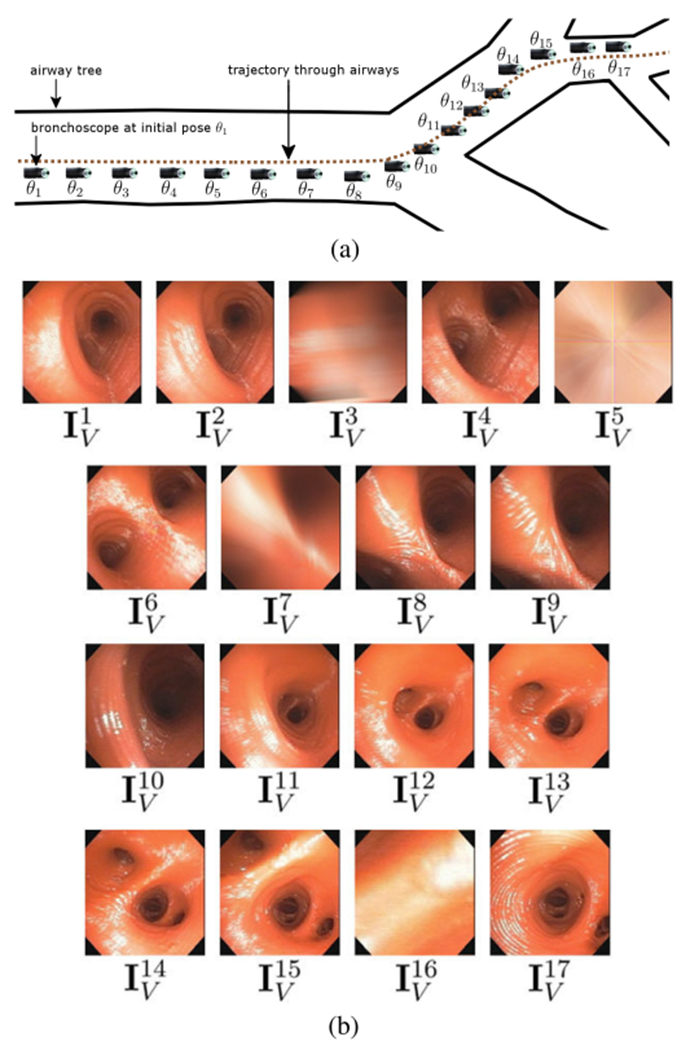

Fig. 1.

A bronchoscope’s trajectory Θ and associated video stream V through three airways. (a) The bronchoscope moves along Θ consisting of 17 discrete poses θ1, θ2, …, θ17; the bronchoscope tip icon represents device position for each pose θk. (b) Corresponding bronchoscopic video sequence V captured along Θ; video frame corresponds to pose θ1, corresponds to pose θ2, etc. Data derived from human phantom case 21405.3a. For this contrived example, we artificially degraded video frames , k = 3, 5, 7, 16, via blurring or obscuration to create uninformative frames. Also, a “real” trajectory through three airways would consist of ≫17 video frames.

The physician freely moves the bronchoscope during the procedure. Fortunately, bronchoscopy’s high video-frame rate implies that the device navigates a smooth path slowly through the airways [24], [26]; i.e., the camera poses and observations change incrementally from frame to frame per

| (3) |

where Δθk is small, and

| (4) |

With respect to (3–4), four incremental bronchoscope movements are possible:

-

1)

Rotation: The bronchoscope rotates along one or more of its axes.

-

2)

Forward or backward translation: The bronchoscope is pushed forward or pulled backward.

-

3)

Hybrid movement: A combination of a rotation and a translation.

-

4)

Hover: The bronchoscope holds still, implying that . The hovering period ends when for some l > k + 1.

As a consequence of (3–4), a subsequence of frames can be found that largely captures the video content of the complete sequence V. To this point, our primary goal in parsing V is to find a keyframe set

| (5) |

that sufficiently summarizes the video coverage of V, where denotes the jth keyframe and 1 ≤ ϕ1 < ϕ2 < … ϕJ ≤ K [7], [10], [27]. We define the video coverage of a sequence {}, k1 < k2 < … < kL, as

| (6) |

where relates to the digital video concept of the video skim and “⊙” is an operation for assembling [10], [28]. For (6), we will aggregate the endoluminal airway surfaces observed by a sequence. Section III fully elaborates on our use of for measuring the sufficiency of the summary offered by Φ.

Motivated by research in multimedia, the task of finding Φ as given by (5) entails the following problem:

Given V, find Φ such that

| (7) |

where D(·, ·) denotes a dissimilarity measure capturing the summarization criteria of interest [10], [29].

Our primary summarization criterion for constructing Φ via (7) will be to minimize the redundancy between keyframes constituting Φ, where we will require a sufficient content change between successive keyframes analogous to related ideas suggested in [30], [31]. In particular, a successor keyframe to will be derived via

| (8) |

where ϵ > 0 bounds the required content change C(·, ·) between the two considered frames. A second complementary criterion will be to reduce the number of frames J constituting Φ, where ideally J ≪ K. We strictly speaking will not minimize J nor place a strict upper bound on J. We will, however, bound J from below by the number of shots partitioning V. Later discussion will detail our realizations of (7–8).

Note that an endobronchial video sequence always contains uninformative interruptions in continuous bronchoscope movement; e.g., views corrupted by mucus or significant motion blur. Hence, V generally consists of contiguous chunks of informative “useful” frames separated by occasional uninformative interruptions not abiding by (3–4). Thus, our secondary videoparsing goal calls for classifying information content of all frames in V, as done in other endoscopy domains [3], [4], [14]. In particular, for each , we will assign a label dk = “informative” if it contains useful information in line with (3–4) and dk = “uninformative” otherwise.

B. Method Overview

Video sequence V acts as the input to our video-parsing method. Before processing, the video stream undergoes a standard real-time radial-distortion correction [32], [33]. For our broad research interests, this facilitates later fusion with a patient’s input chest CT scan and also serves as a standard operation for image-guided bronchoscopy [34]–[37]. To tackle (7), our method consists of three phases, as schematically illustrated in Fig. 2 and summarized below:

-

1)Shot Segmentation—Sequence V is partitioned into a series of shots, resulting in the assignment of frame-classification labels {dk, k = 1, 2, …, K} to all frames , with informative frames being grouped into shots Si in shot set

(9) -

2)

Motion Analysis—An intra-shot bronchoscopy motion profile {Qi , Mi, Ei} is derived for each shot Si, i = 1, 2, …, N, where Qi captures the running bronchoscope motion, Mi labels the motion type, and Ei measures the motion energy.

-

3)

Keyframe Selection—Information gleaned from shot segmentation and motion analysis is combined to identify a keyframe set Φ per (5).

Fig. 2.

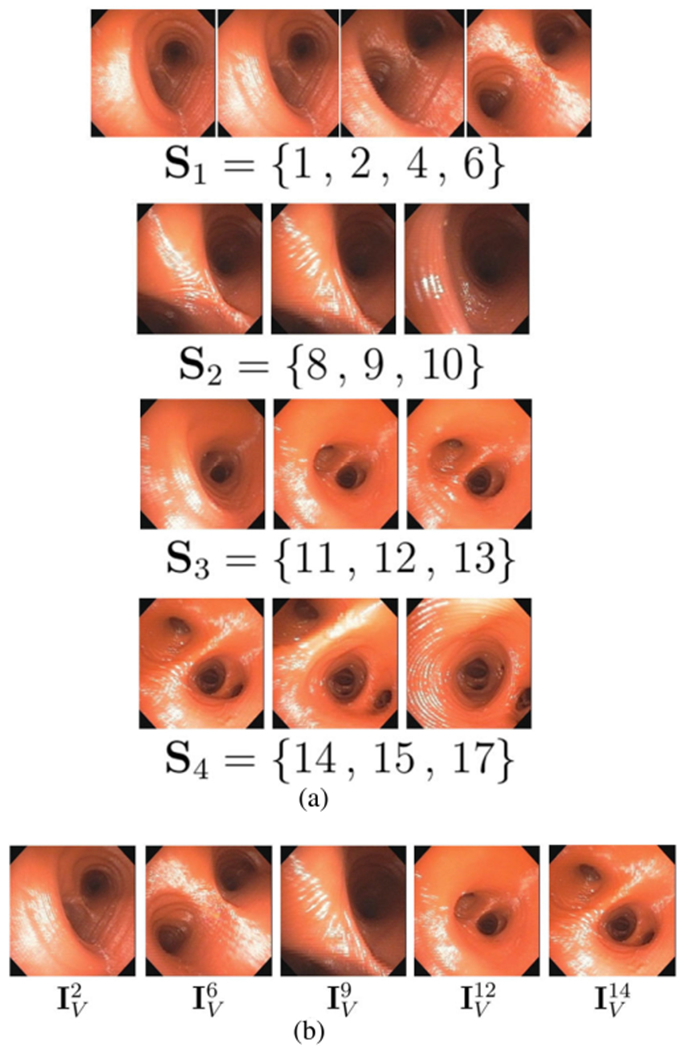

Video parsing for Fig. 1 sequence. (a) Shot set Ψ = [Si, i = 1, 2, 3, 4}; labels dk = “informative” assigned to frames belonging to a shot, while remaining frames , k = 3, 5, 7, 16, have dk = “uninformative”. (b) Final keyframe set . (Since all motion is forward in this example, motion analysis output is omitted.)

The final outputs of parsing V are: 1) frame-classification labels dk for all frames ; 2) shot set Ψ accounting for all informative frames; and 3) keyframe set Φ summarizing V’s video coverage.

Regarding the significance of each phase, Shot Segmentation constructs an initial partition of the raw video sequence into a series of shots, similar to the shot concept used in multimedia. An endoscopic shot, however, is not a planned (scripted) action, but can still be approximately delineated by clear endpoints (e.g., an airway endpoint) to facilitate endoscopic video decomposition into a series of shots. As a major departure from scripted multimedia, shot segmentation also detects uninformative frames, while retaining informative data including all “redundant” video.

Motion Analysis, a universally accepted notion in multimedia-based video summarization [7], [11], has also been suggested recently for endoscopic video analysis [22], [27]. Motion analysis helps characterize subsequences within each shot for later keyframe selection and also provides some measure of frame redundancy (i.e., frames in hover subsequences).

Keyframe selection, which also has a longstanding history in video analysis [9], [10], employs motion-subsequence identification followed by content-change analysis to identify the keyframes. The keyframes summarize the entire space observed during a procedure, provide still-frame views for skimming each shot’s local content, and serve as anchors into the entire video sequence during later video retrieval [10]. Our later results show that the keyframes do in fact capture most of a video’s information content.

The final computed video summary provides an automatically derived hierarchical decomposition of a procedural video. Section III-C later illustrates how this summary gives a complete data structure for representing and browsing a large video sequence. Complete detail for each method phase appears below.

C. Shot Segmentation

As Schoeffmann et al. point out, live endoscopic videos contain much highly similar content, exhibiting minimal obvious shot boundaries, and are also corrupted by unpredictable interruptions [5]. Thus, common shot-detection methods like those proposed by Smeaton et al. for multimedia cannot be used with endoscopic video [13]. We introduce the concept of an endoscopic shot, which is partly motivated by the sub-map organization of cystoscopy video sequences presented by Bergen et al. [38].

We define a shot as a subsequence of video frames viewing a continuous significant event, with consecutive shots being demarcated by a dramatic local-content change between contiguous informative frames. For bronchoscopy, a transition to a new shot typically corresponds to the navigation from one major airway to another via a bifurcation. Shot segmentation consists of three stages: 1) Initialization; 2) Frame Matching; and 3) Shot Assembly.

After initialization, a frame-matching method draws upon image features and two geometric camera models to identify sequential matching frames. A shot-assembly algorithm then partitions input sequence V into a series of shots. This results in the assignment of frame-classification labels and finalizes the partitioning of the entire raw video into shots. Complete detail appears below.

Initialization begins the first shot S1 as

where i = 1 denotes the shot index and initial frame is given frame-classification label d1 = “informative.”

Frame Matching next determines if each successive video frame of V either:

-

1)

Warrants inclusion in the current shot.

-

2)

Signals the beginning of a new shot.

-

3)

Is uninformative and should be excluded from further consideration.

Frame Matching draws upon the computer-vision operations of image-based camera-pose and motion estimation [39], [40]. Without loss of generality, consider the problem of determining if matches IV in frame pair (). Our process entails extracting robust image features from each frame and then fitting these features to two geometric models to determine if the frames have sufficiently similar joint content in line with incremental bronchoscopic motion conditions (3–4). Our method expands upon the approaches used by Soper and Brischwein, which entailed SIFT feature extraction, correspondence calculation, and homography estimation [19], [20]. In particular, Frame Matching enables robust inference of content similarity between nearby frames via a five-step process:

-

1)

Feature analysis.

-

2)

Initial feature-correspondence calculation.

-

3)

Fundamental matrix estimation, to isolate feature matches abiding by a common epipolar geometry.

-

4)

Homography estimation, to isolate feature matches that also fit a locally coplanar model.

-

5)

Final match decision.

This process adds extra robustness over the aforementioned approaches by including a modeling constraint involving the fundamental matrix. In addition, the match-decision step adds a separate homography-based condition-number test to help assess a frame’s information quality and whether or not it could signal the start of a new shot. With the extra rigor introduced by these steps, we not only identify matching frames, but also facilitate full shot segmentation. Full detail appears below.

Frame Matching begins by computing image feature sets (X, X′) and associated feature descriptors for frame pair (). Many robust feature detectors exist for this purpose. As discussed in Section III, we employ the SURF feature extractor in conjunction with BRIEF feature descriptors [41], [42]. An initial set of feature correspondences is next established by first computing the Hamming distances between all inter-frame feature pairs and then selecting the nearest-neighbor match for each feature, taking care to enforce one-to-one feature-match correspondences.

Many initial correspondences will be invalid outlier feature matches. To infer the true underlying airway structure observed by V, the next two steps of Frame Matching employ geometric modeling to establish the correct inlier feature matches. As a first step, we estimate 3 × 3 fundamental matrix F which encodes the epipolar geometry via relations

| (10) |

between frame pair () for point pair and and epipolar lines (Ll, Lr) [39]. We use the 8-point algorithm combined with RANSAC (random sample and consensus) to estimate F [43], [44]. The process iteratively selects feature matches for model estimation and returns the estimate F that maximizes the number of inlier feature matches. The inlier feature matches are retained in (X, X′) for subsequent homography estimation [19], [38].

The 3 × 3 homography matrix H relates coplanar points in two images via the relation

| (11) |

in line with (3) [39]. Conversely, if the bronchoscope poses between () differ excessively due to substantial 3 D motion or major frame differences, then (11) will produce an ill-defined homography H. To estimate H, an iterative least-squares RANSAC-based approach calculates a homography based on a randomly selected subset of 4 feature correspondences, and a backprojection error

| (12) |

is computed over all current inlier feature matches with respect to H’s parameters, h11, h12, etc. [43]. The method returns the matrix H giving the lowest error, with feature matches not well-predicted by the final H being pruned from (X, X′).

Matching inlier features must be ≤ 3 pixels apart in space for estimating F in (10). To put a premium on robustness by retaining as many feature matches as possible, we allowed a more liberal ≤ 6 pixel spacing of matching inlier features for estimating H via (12). Our choices align with typical computer-vision applications [39].

To reach final match decisions, we compute a content-similarity measure, referred to as the condition number, based on the estimated H

| (13) |

where condition(H) measures the change in predicted pixel location p′ per (11), given small perturbations in p [45], [46]. Matching frames should have a small condition number, implying incremental motion, and sufficient matching inlier features, indicating a high-quality motion estimate. Thus, if

| (14) |

then is said to match IV, is labeled as informative (d′ = “informative”), and added to the current shot Si under construction. If fails (14), then it is either uninformative (d′ = “uninformative”) or possibly a member of a new shot. In (14), γ equals the number of inlier features matches used in (12), while TH and Tγ are parameters. The online supplement gives a frame-matching example illustrating how the combined use of the F and H matrices helps eliminate outlier features, resulting in more robust frame matching.

Shot Assembly concludes Shot Segmentation to spawn the final shot set (9), with Algorithm 1 detailing the complete Shot-Segmentation process. Shot assembly, which is interleaved with frame matching, identifies the temporal distances between matching frames and shot boundaries to form distinct shots. The algorithm begins by initializing Si, the current shot under construction. It then cycles through all K frames of V to build shot set Ψ and assign class labels dk to all frames . The basic construction process focuses on the local segment of frames within V given by

where the bracketed frames denote Si’s current state, k1 and k2 indicate Si’s first and current last frames, and is the current frame under test. Lines 1-1 of Algorithm 1 perform frame matching with frame pair (), with function Match() executing the first four Frame-Matching steps. Lines 1-1 augment shot Si with a matched frame, while lines 1-1 consider cases when the test frame does not match. In particular, at lines 1-1, the search for matching frames continues, where no more than δ = 30 frames (1 sec of video) can be skipped before a new shot must begin. Lines 15-25 start a new shot under two circumstances: 1) current shot Si is valid—i.e., consists of at least 3 frames (beginning, middle, end)—and can be finalized; 2) Si is invalid, as it starts with an uninformative frame, and must be restarted.

At the conclusion, all video frames have frame-classification labels dk, k = 1, 2, …, K, and all informative frames are assigned to distinct shots in set Ψ = {Si ; 1, …, N}. The online supplement illustrates frame matching, while Fig. 2(a) illustrates shot segmentation.

D. Motion Analysis

Motion analysis provides information used later during keyframe selection. As stated earlier, motion analysis has been used universally in both multimedia and recent endoscopy research as a mechanism to help identify keyframes. While multimedia applications often additionally use visual features based on RGB/HSV color histograms to identify significant changes signaling keyframes [10], [11], Primus recently pointed out that such features are not applicable to endoscopic video because the color content changes vary very little from frame to frame [22]. Our work incorporates a scoring function originated in the endoscopy research of von Ohsen, who constructed a connected graph to discriminate between forward and lateral laparoscope movements [27]. We also build upon ideas employed by Zhu’s InsightVideo mulimedia system, which classified different types of camera motion [11].

Algorithm 1:

Shot Segmentation.

| 1: | Input: video sequence |

| 2: | shot set Ψ = {∅} // Initialize data structures i = 1, , d1 = “informative” k1 = 1, k2 = 1, kt = 2 |

| 3: | while k2 < K do |

| 4: | // Perform frame matching |

| 5: | Match |

| 6: | Compute condition(H) using (13) |

| 7: | if condition(H) ≤ TH and γ ≥ Tγ then |

| 8: | // Add test frame to shot Si |

| 9: | , dkt = “informative” |

| 10: | k2 = kt, kt = kt + 1 |

| 11: | else // test frame not in Si |

| 12: | dkt = “uninformative” |

| 13: | if kt − k2 < δ and kt < K then |

| 14: | kt = kt + 1 // Continue building Si |

| 15: | else // Start new shot |

| 16: | if Si is valid (has > 2 frames) then |

| 17: | Ψ ∪ Si → Ψ |

| 18: | i = i + 1, k1 = k2 + 1 |

| 19: | else // Si not valid |

| 20: | dk1 = “uninformative” |

| 21: | k1 = k1 + 1 // Restart Si |

| 22: | // Initialize new shot |

| 23: | dk1 = “informative” |

| 24: | |

| 25: | k2 = k1, kt = k1 + 1 |

| 26: | Output: Ψ, {dk, k = 1, 2, …, K} |

After shot segmentation, the typical shot will consist of many redundant frames that add little or no information to the shot’s overall video coverage; e.g., a bronchoscope hovering subsequence. Motion analysis gives clues to the redundancy of shot frames—the greater the motion between a pair of frames, the less redundant they are likely to be. Motion analysis classifies bronchoscope motion for the frames constituting each shot Si in the form of a bronchoscope motion profile {Qi, Mi, Ei}.

For a given shot Si, we first estimate the relative inter-frame motion over the shot, as given by the running-motion signal

| (15) |

where ni is the number of frames constituting Si and each Qi(·) denotes the distribution score between successive intra-shot frame pairs constituting Si, as suggested by von Ohsen et al. in a preliminary effort in laparoscopy [27]. The distribution score Q for a frame pair () having matched inlier feature sets (X, X′) is given by

| (16) |

where each () is a matched feature pair in (X, X’),

| (17) |

is the center of mass of X’s features, and is the Euclidean distance in pixels between xa and (an analogous form of (17) applies for the X’ dependency in (16)). Q measures the change in average distance from the center of mass of all feature matches between IV and . As such, it gives a measure analogous to the bronchoscope’s instantaneous velocity between the two frames.

We next compute a motion-direction signal Mi = {Mi(n), n = 1, 2, …, ni}, where Mi(n) categorizes the motion direction of the nth video frame of Si [11]. Possible values of Mi(n) are “forward,” “backward,” and “hover,” depending on the bronchoscope’s movement, and are assigned as follows:

| (18) |

In (18), video frames exhibiting negligible motion are deemed to be “hover” frames, per thresholds TF and TB.

As a final quantity, we compute the motion energy signal Ei = {Ei(n), n = 1, 2, …, ni}. For each frame pair () and associated feature sets (X, X′), we compute a component E constituting Ei as follows. First, we compute a local motion vector between each feature pair () as the location difference between the pair. Motion energy E is then given simply as

| (19) |

with Ei collecting the ni calculations of (19) for all frames constituting Si. Note that to begin computation of {Qi, Mi, Ei}, we initialize Qi(1) = Ei(1) = 0 and enforce the constraint Mi(1) = Mi(2).

Our approach for using the motion profile focuses on measuring the bronchoscope’s overall 3D camera motion (ego motion) in real space, with an emphasis on detecting forward/backward movement [27]. Most incremental bronchoscope movements, however, are in principle hybrid. Yet, because a bronchoscope’s diameter is comparable to that of the airways, its motion is generally dominated by the forward/backward component (push forward or pull back). Along this line, if the bronchoscope does make a pure incremental rotation between frame pair () then the bronchoscope’s video coverage does not change between the two frames, implying that one of the frames is redundant. Our video profile calculations flag this situation, as such a frame pair has a distribution score Q = 0 per (16), implying no forward/backward movement between the frames.

The initial estimates of the motion signals generally exhibit excessive frame-to-frame fluctuations. This obscures the major underlying bronchoscope movements leading to video sequence V. Thus, to smooth fluctuations, we apply a 5-point moving average filter to signals Qi and Ei and a a 5-point median filter to Mi, where repetition is used to handle boundary conditions. These calculations give the final bronchoscope motion profile {Qi, Mi, Ei} for each shot Si, i = 1, …, N. Fig. 3 gives an example profile for a 51-frame shot.

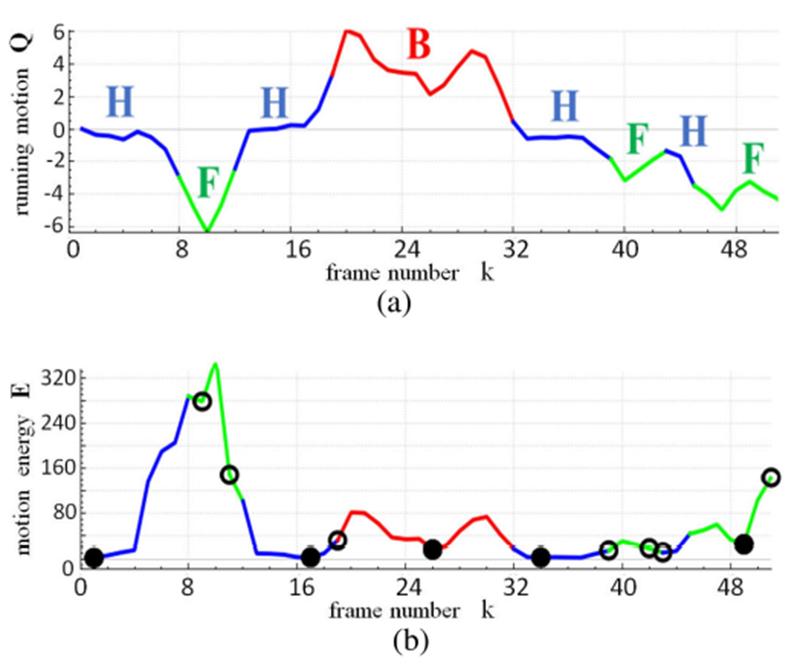

Fig. 3.

Motion analysis and keyframe selection for a 51-frame shot S near the main carina for case 21405.3a. (a) Running motion signal Q, with colors indicating motion direction signal M (green = forward [F], blue = hover [H], red = backward [B]); F, H, and B labels indicate contiguous runs (subsequences) of consistent motion. (b) Motion energy signal E and associated color-coded signal M; open circles indicate initial candidate keyframes derived from motion information and temporal gap filling, while solid circles indicate final keyframe set .

E. Keyframe Selection

Video parsing concludes with keyframe selection, whereby the redundancy inherent in the frames constituting each shot is reduced to give a representative keyframe set Φ. Our method first uses an iterative process drawing on the motion profile to subdivide each shot into motion subsequences, similar to Zhu [11], to establish an initial candidate keyframe set. We then use a homography-based content-change test to prune redundant frames from the candidate keyframe set.

For a given shot and its corresponding bronchoscope motion profile {Q, M, E}, we do the following. Based on motion-direction signal M, S is first partitioned into contiguous runs of consistent motion [11]. For example, the 51-frame shot of Fig. 3 is partitioned into 8 runs, with frames 1-7 constituting a hover run, frames 8-12 a forward run, etc. Candidate keyframe set Φ is next initialized via two criteria. For a hover run, the video frame with minimum motion energy E is selected as a candidate keyframe. For a forward/backward run, we first subdivide it into two segments situated before and after the frame having maximum E; the minimum-E frame in each segment is then selected.

Candidate set Φ is likely to consist of consecutive keyframes separated by an excessively long time interval. This can result in unacceptable gaps in Φ’s video coverage. To ensure that Φ sufficiently spans shot S’s video coverage, we next fill temporal gaps in Φ so that no gap ≥ TK frames exists between any pair of consecutive candidate keyframes. If a keyframe pair violates this criterion, a new keyframe, which exhibits a locally minimal E and is > TK frames from each member of the pair, is inserted into Φ. This procedure is iterated until no new keyframes are inserted.

Augmented candidate set Φ, however, could still contain redundant keyframes, which add little to the overall video coverage. This arises for two reasons: (1) consecutive keyframes may observe very similar video content; (2) certain parts of the sequence may entail backing up to regions observed earlier in the sequence (recall that the bronchoscope can be pulled backward!). Therefore, we next locate and prune such redundant keyframes. In particular, for each and every keyframe pair , we first determine the homography H relating the keyframes using (11–14). We then test if

| (20) |

where C(·,·) represents the content-change function (8) and I is the 3 × 3 identity matrix. If satisfies (20), then it exhibits sufficient content change to warrant retention in Φ. Otherwise, if is small—i.e., H ≈ I, then the bronchoscope poses producing frames () clearly differ little, implying that has nearly the same information content as IV. This completes the definition of the keyframe set Φ for shot S.

Applying the process above for all shots Si, i = 1, 2, …, N, gives the final keyframe set Φ. With respect to (5), the number of frames J constituting Φ is bounded by

| (21) |

where Kinf ≤ K is the number of informative frames found by shot segmentation in sequence V. Per (21), we require every shot to have at least one representative keyframe in Φ. Conversely, as later results will demonstrate, J is generally much smaller than Kinf. Fig. 3 illustrates keyframe selection.

III. Results

Section III-A first introduces all study data and performance metrics used in our validation studies. Next, Section III-B presents method results. Finally, Section III-C illustrates our method’s use in a bronchoscopic video-analysis system under development. An on-line supplement accompanying this paper gives additional experimental details and results.

A. Experimental Set-Up

We used 20 video sequences for our studies, consisting of a total of 82,362 frames (Tables I–II). As listed in Table I, 10 sequences, labeled A-J, served as the prime training set for parameter-sensitivity studies and establishing parameter operating-point values. Per Table II, the remaining 10 sequences, labeled 1-10, served as the prime test set for studying our parameter-optimized method. Each sequence was derived from a lung-cancer patient procedure performed for one of our recent bronchoscopy studies [37], [47], [48]. The videos were drawn from 10 patients and one phantom human airway-tree case. All patients were consented under an IRB protocol approved by our University Hospital. The physicians drew upon Olympus bronchoscopes that output either standard-definition (640 × 480 frame size) or high-definition (1920 × 1080 frame size) video. All but two sequences were collected at a rate of 30 frames/sec, with phantom sequences A-B collected at 19 frames/sec.

TABLE I.

Short Video Sequences Used for Method Training. “Seq” Denotes the Sequence Number, “Frames” Equals the No. of Frames K in a Sequence, and “Inform” Denotes the Number of Ground-Truth-Labeled Informative Frames. High-Definition Sequences Are Indicated by an “*”; All Others Are Standard Definition

| Seq | Frames | Inform |

|---|---|---|

| A | 144 | 142 |

| B | 333 | 325 |

| C | 132 | 132 |

| D | 197 | 194 |

| E | 257 | 257 |

| F | 167 | 121 |

| G | 226 | 211 |

| H | 286 | 184 |

| I* | 342 | 231 |

| J* | 225 | 157 |

TABLE II.

Long Test Video Sequences. “Seq” Denotes the Sequence Number. “Frames” Equals the No. of Frames K in a Sequence. High-Definition Sequences Are Indicated by an “*”; All Others Are Standard Definition. Sequences 1-5 Have Partial Ground-Truth Information Associated With Them, While 6-10 Are Raw Sequences

| With Seq | Ground Truth Frames | Raw Seq | Sequences Frames |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,268 | 6 | 27,325 |

| 2 | 1,119 | 7* | 2,495 |

| 3* | 8,844 | 8* | 13,719 |

| 4 | 6,734 | 9* | 6,378 |

| 5 | 7,457 | 10* | 4,714 |

As a special note, we included three test sequences produced via devices not using traditional white-light bronchoscopy. Sequence 6 was produced by an autofluorescence imaging bronchoscope (300 × 288 frame size), while sequences 9 and 10 were produced by narrow-band imaging bronchoscopy [49], [50]. In this way, we made an initial test of our method’s broader applicability.

Training set A-J (Table I) are fully ground-truthed short excerpts traversing a few airways (2,309 frames total; length range: 5 to 12 sec), with sequences A-E being especially clean. Test set 1-10 (Table II) are long videos traversing many airways over multiple generations in both lungs (80,053 frames total; length range: 37 sec to 15 min), with sequences 1-5 having partial ground-truth information associated with them. Sequences 1, 2, 3, 7, and 9 are relatively clean, while sequences 4, 5, 6, 8, and 10 contain ≥ 30% uninformative data. Discussion of the ground-truth process appears below.

Note that a bronchoscopy procedure exhibits considerable variation from one patient to the next. Except for the phantom sequences, we had no control over the quality and content of a given sequence. Variations arise from patient events, such as coughing bouts, and from a physician’s procedural decisions, such as performing lavage, hovering over a site, etc. Also, occasional procedures may be fraught with difficulty because of a patient’s condition, making most of the video—and, possibly, the procedure itself—of little diagnostic value. Thus, these factors make it nearly impossible to define an “average” video. In addition, our database incorporates videos produced by physicians having widely varying experience levels, including first-year clinical fellows and experienced senior bronchoscopists. Furthermore, because of the unpredictability of a procedure’s flow, a physician used a wide range of movements—slow or fast, forward or backward—in basically all procedures, regardless of a physician’s experience level. As a counterpoint, since the bronchoscopic video stream consists entirely of views inside the airways, the video can give the impression of being highly monotonous, with everything seeming to look the same. This adds to the challenge of picking “the” pertinent video frames summarizing a sequence. Overall, we believe our selection of videos, consisting of over 82,000 frames captured with many different devices, makes a reasonable attempt to capture the variety encountered in bronchoscopy.

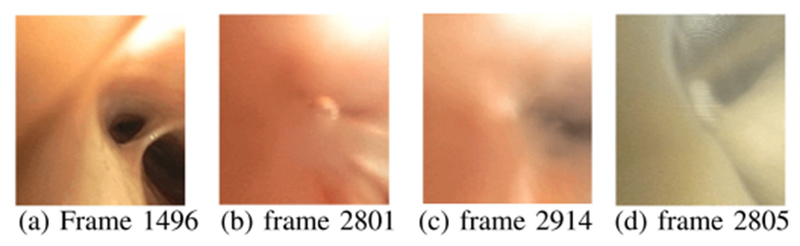

The ground-truth information associated with the sequences in training set A-J (Table I) was important for making an initial assessment of method performance and setting operating-point parameter values (Section III-B1). To this end, for each short sequence A-J, we first assigned the following labels to every constituent video frame : 1) informative/uninformative label dk; and 2) forward/backward/hover label Mk in line with (18). Fig. 4 gives examples of informative/uninformative frames. To compensate for this task’s subjectivity, we assigned labels to all frames over three independent trials. Only frames labeled as “uninformative” over all three trials received this label in the final ground truth. We point out that a majority of uninformative frames tended to occur in subsequences, such as during a coughing episode, making them relatively easy to identify. Finally, the assignment of motion labels proved to be straightforward, with only the “hover” labels posing any ambiguity (see Section III-B below).

Fig. 4.

Examples of informative and uninformative frames. (a) Informative frame from sequence 4. (b)–(c) Uninformative frames from sequence 4 during a bronchoalveolar lavage. (d) Uninformative frame from sequence 5.

For each short sequence A-J, we next mapped the video sequence to a known airway endoluminal surface model. For this task, we drew upon the high-resolution 3D chest computed-tomography (CT) scans associated with all patients. The 3D chest CT scans, collected with a multi-detector Siemens CT scanner, had transverse-plane (x−y) resolution Δx, Δy < 1.0 mm and 2D section thickness/spacing Δz = 0.5 mm. Thus, video-sequence mapping entailed the following steps using existing methods: 1) construct the airway tree’s 3D endoluminal surface model via CT-based airway-tree segmentation and surface definition [51], [52]; 2) register every video frame to the 3D CT surface model, whereby we first interactively registered selected frames to the model and then automatically registered all other frames using a sequential method drawing upon the interactive registrations [24], [35]; 3) texture map each video frame onto the 3D CT surface model using a data fusion/mapping process that integrates the registration knowledge [53]–[55].

Fig. 5 gives a CT-video registration example for step 2. Step 3 associates local CT-based depth data with each mapped video patch and establishes the sequence’s ground-truth video coverage . We define per (6) as a surface mosaic of the aggregated endoluminal airway surfaces observed by video sequence [19], [38], [56]–[58]. The on-line supplement gives an example ground-truth profile for video sequence H and provides other details. Reference [24] gives complete detail.

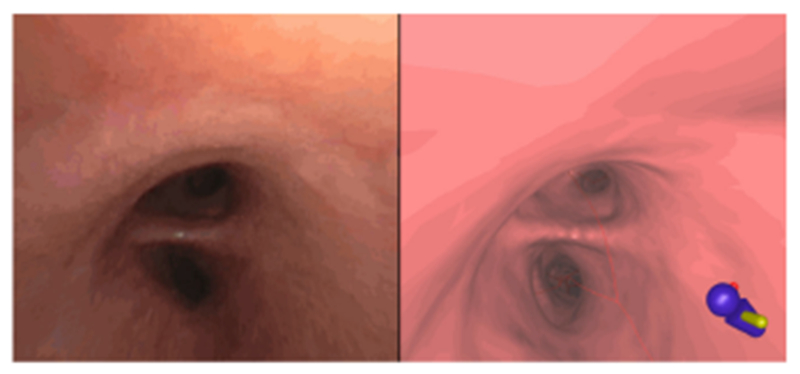

Fig. 5.

Example registration of CT-based virtual bronchoscopy view (left) to a video frame (right) in ground-truth sequence I. (Graphical icon in lower-left corner of CT-based view indicates the patient’s orientation within the airway-tree model.)

Long sequences 1-10 (Table II), which were used for testing the optimized method, generally did not have detailed ground truth associated with them (Section III-B2). Along this line, for sequences 1-5, we only performed CT-based video sequence mapping, as label assignment was extremely impractical. For these sequences, we performed mapping as described above to arrive at a ground-truth video coverage . Finally, for long sequences 6-10, we established no ground truth.

For performance metrics, we consider accuracy, which denotes the percentage of frames receiving correct informative/uninformative labels dk relative to the ground-truth. In addition, we use the video abstraction ratio

| (22) |

to measure the efficiency of a keyframe set Φ to represent V, in line with (1) and (5), and the video-coverage fraction

| (23) |

where denotes Φ’s video coverage per (6) and is the CT-based ground-truth video coverage of V. As a final note, all tests below were performed on a dual 2.8-GHz six-core Dell Precision T5500 PC running the Windows 7 OS. The PC utilized 24 GB RAM and an nVidia Quadro 4000 2-GB PCIe graphics card. All code was implemented using C++ and Visual Studio 2012. Parts of our method drew upon modified functions for feature extraction, correspondence identification, and RANSAC contained in the OpenCV 2.4.11 computer-vision C++ library [59]. We did not optimize code for performance, nor did we explicitly program multi-CPU operations or operations to run on the nVidia GPU.

B. Method Results

Section III-B1 first presents a series of training studies to ascertain our method’s robustness to parameter variations and to establish operating-point parameter values for later tests. All training studies drew upon the 10 fully ground-truthed short sequences A-J (Table I), except for the initial feature-analysis study, which employed long sequences 1 and 2. Next, Section III-B2 gives studies that test the parameter-optimized method using the 10 long sequences of Table II.

1). Training Studies (Parameter Optimization):

We first tested six well-known computer-vision techniques for feature analysis in shot segmentation, using long sequence 1 [41], [42], [60]–[63]: SIFT, SURF, BRIEF, FREAK, BRISK, and ORB. See the on-line supplement for complete results for these studies. Fundamentally, all techniques gave viable results. Yet, the SURF feature extractor combined with the BRIEF feature descriptors gave the lowest computation time (128 sec), highest percentage of frames assigned to shots (93.0%), fewest number of segmented shots (N = 12), and smallest keyframe set (J = 71). While ORB was most efficient computationally (112 sec), it designated an excessive 32.3% of frames as uninformative. BRIEF’s efficiency is expected, as it entails simple binary-valued feature descriptors. A second test of the six feature-analysis methods using long sequence 2 confirmed our quantitative observations based on sequence 1. Given these results, we drew upon the SURF feature extractor and BRIEF feature descriptors for all subsequent tests. (Section IV later points out that while popular feature detectors, such as SURF and SIFT, have been used successfully in other endoscopic video applications, they are known to be susceptible to image glare and other degradations. Hence, more advanced feature detectors could add performance robustness.)

The next series of studies measured our method’s sensitivity to parameter variations to establish operating-point parameter values. A summary of these studies appear below, with the online supplement giving additional results.

To begin, the more inlier features we require for matching frames (i.e., higher Tγ in (14 b)), the more stringent is the matching condition. Hence, an excessively high Tγ can have the undesirable effect of rejecting more informative frames. Thus, it is prudent to pick a low value of Tγ, implying fewer matching inlier features are needed for candidate matched frames. Fortunately, we found that a wide range of Tγ gave similar results. In particular, for 9/10 sequences A-J, an accuracy ≥ 87% was achieved for Tγ ≤ 20 in (14 b), with the large majority of matched frames having γ > 30 inlier matched features. Sequence F’s lower accuracy arose because of a subsequence of 46 low-quality blurry frames (out of 167 total frames) having fewer feature matches. Choosing Tγ = 33 rejects most of these frames, raising the accuracy. But as stated earlier, a higher Tγ can result in excessive rejection of informative frames, adversely lowering the accuracy for the other sequences. Thus, we chose Tγ = 8. As this choice is the minimum required for RANSAC-based F estimation in (10), it effectively nullifies this parameter’s impact.

We next noted consistent performance over the wide range [15,000, 409,600] for TH in homography test (14 a) [409, 600 = 400 · 210]. Thus, we picked TH = 102,400 (= 100 · 210) as the operating-point value. Similarly, motion analysis proved robust over the wide range [±0.9 pixels, ±2.9 pixels] for thresholds TF and TB in (18), with TF = −1.9 and TB = 1.7 chosen as operating-point values. The one minor consequence of harsher thresholds is that more frames become labeled as “hover” locations.

TK ≤ 18 frames (≤ 0.6 sec gap between keyframe candidates) enabled sufficient gap filling in the initial candidate keyframe set such that video-coverage fraction Γ (Φ, V) > 90% was achieved for all sequences. This further attests to bronchoscopic video’s redundancy. We conservatively chose TK = 5 to give greater flexibility in picking final keyframes in set Φ. Finally, as ϵ increases in keyframe-removal test (20), the final number of keyframes J and Γ(Φ, V) decreases. This decrease leveled off for ϵ ≈ 41 (considered range: [1,351]), with a wide range giving similar performance for J. Since a larger ϵ can begin to adversely affect the video coverage Γ(Φ, V), we chose the conservative value ϵ = 41, which gave a keyframe set Φ drawing on an average of 7.2% of the total number of frames K in a given V, with mean coverage fraction = 92%.

In summary, we arrived at the following operating-point values for all subsequent tests: Tγ = 8, TH = 100 · 210, TF = −1.9, TB = 1.7, TK = 5, ϵ = 41. Tables III–IV give baseline performance measures for the optimized method for training sequences A-J. (Section III-B2 studies the optimized method for test sequences 1-10 of Table II.) Table III gives shot-segmentation results, while Table IV considers complete parsing. (Regarding Table III, recall that sequences A-E have almost no uninformative frames per Table I.)

TABLE III.

Shot-Segmentation Results for Ground-Truth Sequences A-J Using Optimized Parameter Values. “Seq” Refers to the Sequence, “N” Is the Number of Segmented Shots in Shot Set ψ, “Accuracy” Denotes the Accuracy in Designating Informative/Uninformative Frames. “Inform” and “Uninform” Refer to the Percentage of Ground-Truth-Labeled Informative and Uninformative Frames Correctly Labeled, Respectively. A Quantity A ± B Denotes the Mean A ± Standard Deviation B Over 5 Trials. “*” Indicates an HD Sequence

| Seq | N | Accuracy | Inform | Uninform |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1 | 98.5 ± 0.3 | 99.8 ± 0.3 | 0 |

| B | 1 | 97.5 ± 0.3 | 99.7 ± 0.4 | 8.5 ± 11.4 |

| C | 1 | 100 | 100 | — |

| D | 1 | 98.5 | 100 | 0 |

| E | 1 | 100 | 100 | — |

| F | 2.2 ± 1 | 83.1 ± 2.5 | 97.8 ± 1.6 | 44.3 ± 7.1 |

| G | 2 | 92.8 ± 0.5 | 97.4 ± 0.6 | 28.0 ± 2.7 |

| H | 7.2 ± .4 | 95 ± 0.4 | 97.7 ± 0.8 | 90.2 ± 0.9 |

| I* | 9.8 ±.8 | 86.0 ± 3.4 | 83.1 ± 4.9 | 92.1 ± 1.6 |

| J* | 12 ± 1 | 90.1 ± 3.4 | 96.0 ± 4.5 | 76.5 ± 2.6 |

TABLE IV.

Complete Video-Parsing Results for Ground-Truth Sequences A-J Using Optimized Parameter Values Over 5 Trials. “Seq” Refers to the Sequence, “J” Is the Number of Selected Keyframes in Φ, Λ Is the Video-Abstraction Ratio (22), and Γ(Φ, V) Is the Video-Coverage Fraction in % Per (23).“*” Indicates an HD Sequence

| Seq | J | Λ | Γ(Φ, V) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 12.6 ± 1.5 | .087 ± .010 | 90 ± 1.0 |

| B | 55.1 ± 2.6 | .165 ± .007 | 97.9 ± 0.4 |

| C | 9.0 ± 0.8 | .068 ± .006 | 88.5 ± 1.1 |

| D | 6.0 ± 0.8 | .030 ± .004 | 87 ± 2.1 |

| E | 10.6 ± 1.4 | .041 ± .005 | 85.6 ± 0.9 |

| F | 17 ± 1.1 | .102 ± .007 | 79.7 ± 7.7 |

| G | 9.9 ± 1.1 | .044 ± .005 | 97.5 ± 0.3 |

| H | 21.3 ± 1.2 | .074 ± .004 | 87.1 ± 1.2 |

| I* | 46 ± 2.0 | .134 ± .006 | 96.8 ± 0.1 |

| J* | 52 ± 1.5 | .231 ± .007 | 98.2 ± 0.1 |

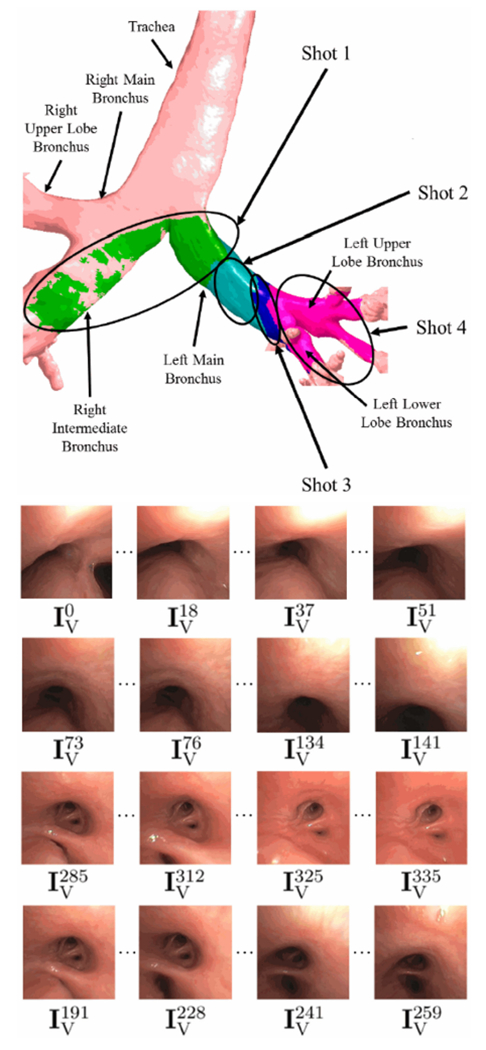

Also, Fig. 6 illustrates video parsing for 342-frame sequence I. The sequence captures a bronchoscope trajectory ranging from the trachea to the left lower lobe. The video coverage shows that the bronchoscope glimpses portions of the right-lung airways during its trajectory. The parsed sequence used J = 36 keyframes, giving a video abstraction ratio Λ = 0.105 and a video-coverage fraction Γ = 0.967. The on-line supplement gives a second example.

Fig. 6.

Example parsing of 342-frame HD sequence I. The top part of the figure depicts the video coverage of the final keyframe set Φ, with separate colors used to represent the coverage of each shot (green for shot 1, aquamarine for shot 2, etc.). Each row of the lower part depicts example video frames constituting each of the four shots (row 1 for shot 1, etc.); All depicted frames were selected as keyframes. Excluding uninformative frames, shot 1 consists of frames in the range 0 ≤ k ≤ 61; shot 2, 73 ≤ k ≤ 141; shot 3, 184 ≤ k ≤ 262; shot 4, 280 ≤ k ≤ 341.

The multi-trial results of Tables III–IV clearly indicate our method’s potential for consistent performance, with 100% accuracy achieved for sequences C and E, which had no ground-truth-labeled uninformative frames. Note that RANSAC introduces a random element that influences the number of matching inlier features found during frame matching. This in turn affects the final set of frames constituting keyframe set Φ. Hence, our method does not lead to a unique Φ for a given V. Nevertheless, the small variations in the number of keyframes extracted and the consistent video coverage achieved offer initial evidence of our method’s robustness to RANSAC-based variations and of the considerable inter-frame redundancy in bronchoscopic video.

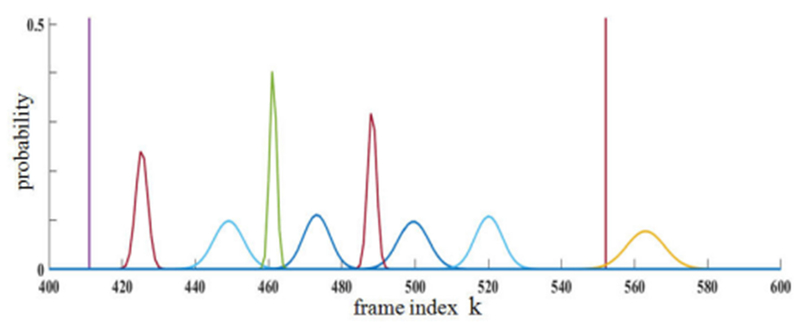

To consider this last point further, we next studied how RANSAC’s stochastic element affects the consistency of the keyframes constituting Φ. Six trials for long sequence 1 using optimized parameter values gave 75 ± 4.9 keyframes selected. To assess keyframe repeatability, we clustered all indices k over all video frames selected over the six trials using K-means clustering (75 clusters) and fitted Gaussian distributions to each cluster. This gave a mixture distribution depicting the likelihood of each frame being selected as a key frame (Fig. 7). Notably, 22 frames were selected as keyframes during every trial, with all other selected frames situated within a small temporal (k) range of each other. Clearly, the video sequence’s considerable redundancy suggests that many contiguous frames have nearly the same video content and, hence, are essentially equivalent to each other. Other experiments corroborated this result [24].

Fig. 7.

Distribution of selected keyframes over six trials for 1,268-frame sequence 1. Plot covers frames selected between 400 ≤ k ≤ 600. Horizontal axis represents frame index k. Vertical axis represents probability ≤ 1. A “spike” at a particular k indicates that every trial selected as a keyframe. Other selected keyframes were clustered and fitted to Gaussian densities.

To further assert a video sequence’s inherent redundancy, we performed another study using sequences A-J, whereby we iteratively searched through all frames in a given V to find the fixed J-frame set Φ that maximizes video-coverage fraction Γ(Φ, V) for a given J. Hence, in principle, these results correspond to the best-case video-summarization, based on measure Γ(Φ, V). Over all sequences, we noted that for J ≤ 12 (i.e., < 8% of the constituent video frames) Γ(Φ, V) ≥ 95% was always possible. Conversely, adding more keyframes (up to J = 35) only increased Γ(Φ, V) to 97%. Hence, a video is clearly highly redundant and extra keyframes beyond a certain limit contribute little to the overall coverage.

2). Method Tests:

Our final series of studies consider our optimized parsing method, using long sequences 1-10 of Table II. To begin, we used partially ground-truthed long sequences 1-5 to compare our method to three other keyframe-selection approaches: random sampling, uniform sampling, and an ORB-based approach previously applied to laparoscopy [5]. Random sampling entails randomly selecting a fixed number of keyframes to represent a sequence, while uniform sampling involves selecting evenly-spaced keyframes across a sequence [5]. The ORB-based approach scans a video sequence with a fixed-width sliding window and performs ORB-based frame matching to identify keyframes. For the test, we performed 5 trials of our proposed method (only 1 trial for HD sequence 3), 10 trials of random sampling, and 1 trial of uniform sampling as it is deterministic. For random and uniform sampling, we picked a J slightly greater than the mean J derived by our method, in effect giving these methods a slight advantage. Because the ORB-based approach gives a fixed deterministic number of keyframes, we included two trials of this method to gauge its performance. Table V gives the results. (We excluded sequence 2, as it is an SD subset of sequence 3.)

TABLE V.

Test Results for Long Sequences 1-5. “Seq” Refers to the Input Sequence,”Method” Refers to the Method Used, Where “Parsing” Refers to our Method, “Random” Is Random Sampling, “Uniform” Is Uniform Sampling, and “ORB-Based” Is the Method of [5]. For the ORB-Based Results, Trial #1 Uses Fewer Keyframes Than Parsing, While Trial #2 Use More. “J” Equals the Number of Selected Keyframes, “Λ” Is the Video Abstraction Ratio (22), and “Γ(Φ, V)” Is the Video-Coverage Fraction (23). “*” Indicates an HD Sequence

| Seq | Method | N | J | Λ | Γ(Φ, V) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Parsing | 2 ± 0.6 | 49 ± 3 | .038 ± .003 | 86.1 ± 5.3 |

| Random | 56 | .044 | 80.4 ± 4.4 | ||

| Uniform | 56 | .044 | 82.6 | ||

| ORB-based #1 | 37 | .029 | 76.4 | ||

| ORB-based #2 | 52 | .041 | 77.8 | ||

| 3* | Parsing | 41 | 667 | .075 | 93.1 |

| Random | 773 | .087 | 91.1 ± .7 | ||

| Uniform | 773 | .087 | 93.6 | ||

| ORB-based #1 | 564 | .064 | 84.3 | ||

| ORB-based #2 | 908 | .103 | 91.3 | ||

| 4 | Parsing | 21 ± 1.3 | 212 ± 8 | .031 ± .001 | 93.6 ± .6 |

| Random | 284 | .042 | 91.5 ± 1.4 | ||

| Uniform | 284 | .042 | 92.4 | ||

| ORB-based #1 | 214 | .032 | 91.3 | ||

| ORB-based #2 | 319 | .047 | 93.4 | ||

| 5 | Parsing | 27 ± 3.5 | 328 ± 16 | .044 ± .002 | 91.3 ± 2.4 |

| Random | 395 | .053 | 80.8 ± 3.2 | ||

| Uniform | 395 | .053 | 82.1 | ||

| ORB-based #1 | 275 | .037 | 75.9 | ||

| ORB-based #2 | 383 | .051 | 83.7 | ||

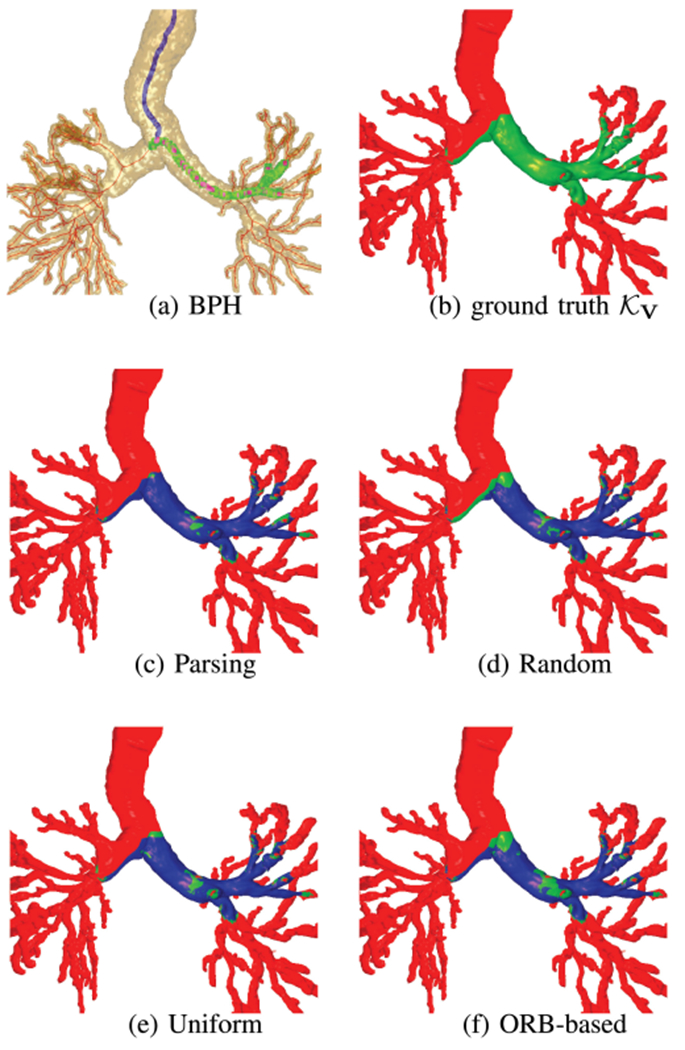

Overall, our method gave a smaller video-abstraction ratio Λ—i.e., requires fewer keyframes J—and superior video coverage Γ(Φ, V) for all considered long sequences. Also, Fig. 8 illustrates the video coverage of all methods versus the ground truth for sequence 5. Note that Table V does suggest that uniform sampling “accidentally” gives a slightly higher video coverage for sequence 3, albeit by using 16% more keyframes. Nevertheless, it is well established that both uniform and random sampling are unacceptable methods for video summarization, as they are prone to two distinct problems [5], [24]: 1) they may miss important short-duration events; 2) they may include and over-represent degraded uninformative data or hovering events. As an example, Figs. 8d-e clearly show how random and uniform sampling can miss important observed regions.

Fig. 8.

Video coverage of various video-abstraction methods for sequence 5. Green = ground-truth video coverage , blue = video coverage of a particular method, and red = regions not observed by the video. In (c)–(f), ground-truth regions not covered by a method remain green. As (d)–(f) show, the competing methods miss significant swaths of the left main bronchus.

While our method performs better than other approaches by several measures, it does entail significant computation. For SD sequence 1, our method required 128 sec, with each step taking the following time: feature extraction, 28 sec; shot segmentation, 30 sec; motion analysis, 4 sec; and keyframe selection, 66 sec. As for the other methods, random sampling required 3.2 sec of computation time; uniform sampling, 2.2 sec; and ORB-based, 2.9 sec. Nevertheless, our method did process sequence 1 at a near real-time 10 frames/sec rate. A similar test with SD sequence 2, however, required 562 sec of processing time (≡ 2 frames/sec). This occurs, because the computation for keyframe selection increases as the final number of keyframes increases. Also, as discussed below, computation increases, as data resolution increases (SD to HD), as highlighted below.

As a final test, Table VI gives method results for long sequences 6-10 (no ground truth), while Fig. 9 gives sample parsing results for sequence 9. We enforced a 15 frame/shot minimum for a valid shot during shot segmentation. Video abstraction ratios ranged from .028 to .117, while video-coverage fractions > 89% resulted for all sequences. Over all long sequences tested for Tables V–VI, our method gave a mean Λ = 0.065 ± 0.030 and Γ = 92.7% ± 3.8%.

TABLE VI.

Test Results for Long Sequences 6-10. “Seq” Refers to the Input Sequence, “N” Is the Number of Shots, “Frame %” Denotes the Percentage of Frames Deemed Informative That Constitute the Shots, “J” Is the Number of Selected Keyframes, “Λ” Is the Video Abstraction Ratio (22), and “γ(Φ, V)” Is the Video-Coverage Fraction (23). Finally, “Computation” Gives Computation-Time Measures ‘Frames/sec (Computation Time in min.).’ “*” Indicates an HD Sequence

| Seq | N | frame % | J | Λ | Γ(Φ, ν) | Computation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 150 | 59.5 | 772 | .028 | 90.9 | 16.7 (27.2) |

| 7* | 25 | 37.9 | 192 | .077 | 96.2 | 0.3 (118.7) |

| 8* | 80 | 65.9 | 1,027 | .075 | 98.1 | 0.7 (348.3) |

| 9* | 36 | 89.8 | 749 | .117 | 97.8 | 0.6 (174.1) |

| 10* | 55 | 60.7 | 493 | .105 | 89.9 | 0.5 (151.8) |

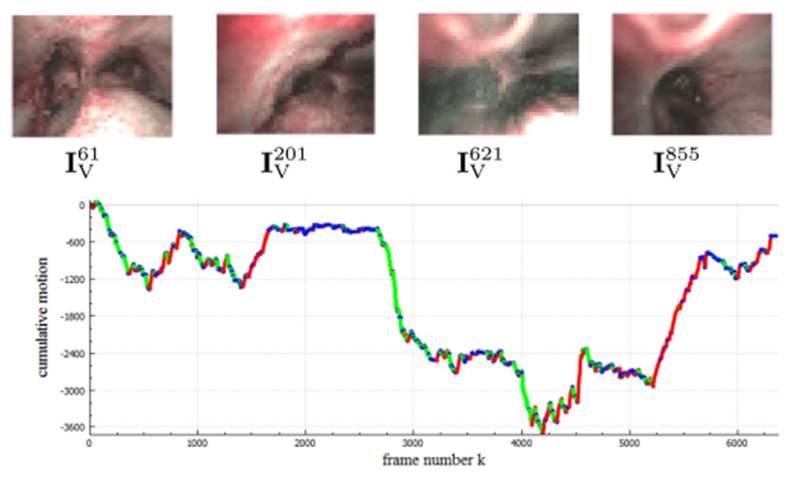

Fig. 9.

Sample parsing results for the 6,378-frame narrowband-imaging sequence 9. Example keyframes (top) and a cumulative motion plot (bottom) are shown; green = forward motion, blue = hover, and red = backward.

Notably, Tables III–VI suggest no quantitative difference in the video coverages between SD and HD sequences, implying that our method gives comparable results for both classes of videos. In fact, video coverage appears to be driven more by what the bronchoscope actually sees during the procedure instead of by video resolution. We believe the performance for SD and HD are similar, because both video classes enable a large number of features to be extracted per frame.

Commensurate with their higher resolution, HD sequences 7-10 demanded substantially more computation than SD sequences, with computation rates ranging from 0.5 frames/sec to 1.6 frames/sec. On the other hand, the small frame size of autofluorescence sequence 6 enabled a very rapid rate of 16.7 frames/sec. Again, we did not optimize our computer code, so improved computational efficiency is possible. Yet, the autofluorescence results point to the potential of downsampling the frames in space x−y to gain computational efficiency. A risk here, though, is that downsampling could conceivably produce less reliable or incorrect parsing results. This could especially affect frame matching and the concomitant rejection of informative frames.

C. Video Analysis System

We have integrated the proposed video-parsing method into an interactive system for bronchoscopic video analysis [23], [24]. The system, prototyped within the framework of our system for the planning and guidance of bronchoscopy [35]–[37], accepts a patient’s 3D chest CT scan and bronchoscopic procedural video V as inputs. It then computes the CT-based airway-tree model and parses the video. Next, semi-automatic registration between the parsed video and airway-tree model, as highlighted in Section III-A, gives a final fused data structure.

This data structure links the parsing outputs (frame labels {dk, k = 1, …, K}, shot set Ψ, motion signals {Q, M, E}, and keyframe set Φ) to the CT-based airway-tree model. Notably, a bronchoscopy path history, which represents the trajectory Θ traversed by the bronchoscope is computed. With this history, the physician now knows for the first time, the precise locations visited in the airway tree during a procedure.

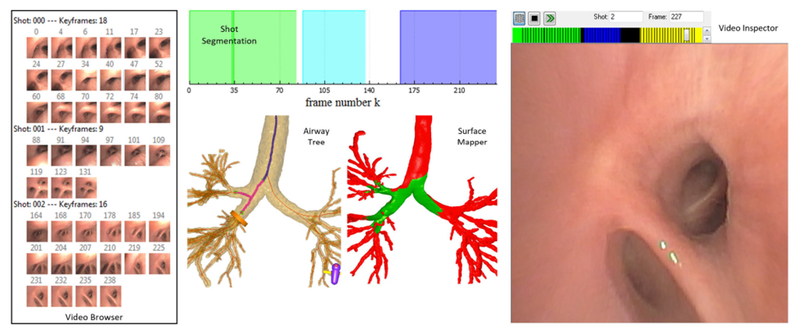

Using the system, the physician can perform numerous video browsing and retrieval operations via a series of interactive tools and a querying mechanism. Among other functions, the physician can note the bronchoscopy’s airway coverage, browse through the video while simultaneously noting its airway-tree position via the CT linkages, and define diagnostically important airway mucosal sites. Fig. 10 shows an example display for a bronchoscopy through a lung-cancer patient’s right lung. References [23], [24] give complete detail.

Fig. 10.

Example view of bronchoscopic video-analysis system for a 239-frame sequence summarized by 3 shots and 43 key frames (patient 20349.3.90). The Video Browser summarizes the shots and keyframes. Shot Segmentation gives a color-coded representation of the sequence. Each color signifies a shot: shot 0 = green; shot 1 = blue; shot 2 = purple; white segments denote uninformative frames. Airway Tree depicts the CT-based airway tree and bronchoscopy path history (magenta airway paths) signifying trajectory Θ traversed by the bronchoscope. Surface Mapper highlights the video’s observed endoluminal surfaces—i.e., its video coverage (green)—relative to the endoluminal airway-tree surface. Video Inspector permits the user to scroll through the video sequence; the scroll bar, color-coded by shot, indicates browser position along sequence (frame in shot 2).

IV. Conclusion

Currently, physicians must rely on memory, notes, and anecdotal snapshots taken during a procedure to incorporate any observations noted in bronchoscopic video. In addition, the challenges posed by airway obscurations (mucus), patient cough, and the ever-present problem of tracking the bronchoscope through the complex branching airway tree make bronchoscopic video summarization difficult. This is especially problematic for patients who must undergo multiple bronchoscopies for lung-cancer monitoring, asthma treatment via bronchial thermoplasty, and mucosal-cancer detection using confocal fluorescence microscopy [64]–[66]. Nevertheless, because the endobronchial video stream offers vivid information for monitoring airway-wall tissue changes for these applications, it is vital that efficient methods be devised for incorporating such information into the clinical work flow [67]. Our video-parsing method could facilitate this goal.

To the best of our knowledge, our method is the first proposed for automatic endobronchial video summarization, and it is also the first proposed for any endoscopy application. Given the method’s ease of use for processing a large video sequence, it could help fill a vital need suggested by past researchers for a more practical and efficient means for endoscopic video browsing and analysis [15], [18], [68]. Given a procedural video, our method outputs a true video summary, per the fundamental notion of the video summary employed in multimedia. In particular, the video summary consists of a complete hierarchical decomposition of a video V into semantic units, via a series of segmented shots Ψ consisting of keyframes in set Φ. With the summary, efficient video browsing/retrieval and linkage to a patient’s 3D chest CT scan are possible. As a result, the physician now has convenient access to full knowledge of what was observed in individual airways and airway sites.

As an additional pointer toward our method’s broader applicability, we successfully applied it to three distinct optical endoscopic modalities: standard white-light bronchoscopy, autofluorescence bronchoscopy, and narrow-band imaging. As such, our methodology could have applicability in other endoscopy domains, perhaps with the inclusion of domain knowledge. For instance, it could prove useful for enabling automatic annotation of colonoscopy video, which heretofore had been done manually, and linkage to an abdominal CT scan [68]–[70]. It could also prove useful in surgery, where the notion of a shot is important in the video segmentation of events such as surgical-instrument insertion [71].

In addition to giving a video summary, our results indicate that our method typically enables higher video coverage via a smaller keyframe set than other keyframe-selection methods. Furthermore, it is robust to parameter variations and gives comparable performance for both SD and HD sequences. Over the range of videos we considered, our method required on average only 6.5% of available video frames to achieve a video coverage = 92.7%. On a related note, we demonstrated that bronchoscopic video inherently has considerable redundancy, greatly facilitating efficient robust video summarization.

The five-step frame-matching method in our parsing approach improve match quality in shot segmentation. In addition, our keyframe-selection method strikes a balance between the temporal difference of candidate keyframes and the number of keyframes retained, while indirectly seeking to attain sufficient video coverage. To this point, our way for solving optimization problem (7) does not explicitly define a dissimilarity measure D(·, ·). Instead, our optimization criteria impose keyframe content-change condition (20) and a requirement that each segmented shot must be represented by at least one keyframe in final keyframe set Φ.

Several areas for improvement and future work warrant discussion. First, given the considerable effort entailed in constructing detailed ground truth for a data source as large as an endoscopic video, our results are based on a method optimized over a limited training database. This is exacerbated by the inherent unpredictability of a bronchoscopic procedure (and the associated video), as discussed earlier. Therefore, performance variations are likely. Thus, more extensive tests would be prudent to better understand performance.

As a second area, three video preprocessing enhancements could be useful. First, an added procedure for detecting uninformative frames, such as the use of metrics measuring image blur or quality, could be beneficial [4], [5], [14], [18].

Second, image glare (specular reflections) are known to degrade the visualization of endoscopic video and certainly affect automated video-analysis methods [6], [72]. Thus, a method that detects and reduces specular highlights could improve our method’s robustness [4], [6], [16], [18], [72], [73]. We note that many bronchoscopic video frames only suffer a mild degradation from specular reflections, as noted in our on-line supplement [74]. This raises the interesting point that some frames straddle an unclear boundary between being informative or uninformative. For instance, a partially corrupted frame could give vital evidence of early cancer on the airway mucosa.

As a third preprocessing enhancement, it is common for portions of bronchoscopic video to be temporarily obscured by water or other secretions. Such frames could be restored through a digital defogging process [75].

Another area for further work is to consider other feature detectors. While our choice of the SURF feature extractor and BRIEF feature descriptor proved to be the best empirically over 6 tested feature options (and our training data), other research in endoscopic video analysis have successfully integrated SIFT, SURF, and ORB [5], [6], [19], [20]. Conversely, SIFT and SURF are known to be problematic in regions corrupted by glare and less textured regions [76], [77]. Thus, a recently suggested detector, drawing on elements of SIFT and SURF, could provide greater robustness to such degradations [78], [79]. Also, an intriguing possibility applied to laparoscopy is the hierarchical multi-affine algorithm used in conjunction with SIFT [80]. Finally, despite the difficulties reported by others [22], it could be beneficial to consider visual color features as a criteria for selecting keyframes [13].

While we did observe video processing rates exceeding 10 frames/sec, method computation time could be improved through code optimization and parallelization. Finally, the significance of the shot and video coverage per (6) warrant more study. Our method, as it stands, does not attempt to maximize per se when constructing keyframe set Φ. Our method could be augmented with an operation that adds additional keyframes that attempt to fill key “gaps” in the video coverage.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

William E. Higgins and Penn State have an identified conflict of interest and financial interest related to this research. These interests have been reviewed by the University’s Institutional and Individual Conflict of Interest Committees and are currently being managed by the University and reported to the NIH. Drs. Rebecca Bascom and Jennifer Toth performed or supervised all bronchoscopies used in this work.

This work was supported by NIH Grant R01-CA151433 from the National Cancer Institute.

Contributor Information

Patrick D. Byrnes, School of Engineering, Penn State Erie, The Behrend College

William Evan Higgins, School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and the Department of Biomedical Engineering, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802 USA (weh2@psu.edu).

References

- [1].Wang KP et al. , Flexible Bronchoscopy, 3rd ed Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lux M et al. , “A novel tool for summarization of arthroscopic videos,” Multimedia Tools Appl, vol. 46, pp. 521–544, Jan. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bashar MK et al. , “Automatic detection of informative frames from wireless capsule endoscopy images,” Med. Image Anal vol. 14, pp. 449–470, Jun. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Munzer B et al. , “Relevance segmentation of laparoscopic videos,” in Proc. IEEE Int. Symp. Multimedia, Dec. 2013, pp. 84–91. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Schoeffmann K et al. , “Keyframe extraction in endoscopic video,” Multimedia Tools Appl, vol. 74, pp. 11187–11206, Dec. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Münzer B et al. , “Content-based processing and analysis of endoscopic images and videos: A survey,” Multimedia Tools Appl, pp. 1–40, Jan. 11, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Liu T et al. , “A novel video key-frame-extraction algorithm based on perceived motion energy model,” IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol, vol. 13, no. 10, pp. 1006–1013, Oct. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zhu X et al. , “Exploring video content structure for hierarchical summarization,” Multimedia Syst, vol. 10, pp. 98–115, Aug. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Xiong Z, A Unified Framework for Video Summarization, Browsing, and Retrieval With Applications to Consumer and Surveillance Video. New York, NY, USA: Academic, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Truong BT and Venkatesh S, “Video abstraction: A systematic review and classification,” ACM Trans. Multimedia Comput., Commun., Appl, vol. 3, Feb. 2007, Art. no. 3. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhu X et al. , “InsightVideo: Toward hierarchical video content organization for efficient browsing, summarization and retrieval,” IEEE Trans. Multimedia, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 648–666, Aug. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Del Fabro M, andBöszörmenyi L, “State-of-the-art and future challenges in video scene detection: A survey,” Multimedia Syst, vol. 19, pp. 427–454, Oct. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Smeaton AF et al. , “Video shot boundary detection: Seven years of TRECVid activity,” Comput. Vis. Image Understanding, vol. 114, pp. 411–418, Apr. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Oh J et al. , “Informative frame classification for endoscopy video,” Med. Image Anal, vol. 11, pp. 110–127, Apr. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Leszczuk M and Duplaga M, “Algorithm for video summarization of bronchoscopy procedures,” Biomed. Eng. Online, vol. 10, p. 110, Dec. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Oh J et al. , “Measuring objective quality of colonoscopy,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng, vol. 56, no. 9, pp. 2190–2196, Sep. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Vilarino F et al. , “Intestinal motility assessment with video capsule endoscopy: Automatic annotation of phasic intestinal contractions,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imag, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 246–259, Feb. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Park S et al. , “A colon video analysis framework for polyp detection,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng, vol. 59, no. 5, pp. 1408–1418, May 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Soper TD et al. , “Surface mosaics of the bladder reconstructed from endoscopic video for automated surveillance,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng, vol. 59, no. 6, pp. 1670–1680, Jun. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Brischwein M, Wittenberg T, and Bergen T, “Image based reconstruction for cystoscopy,” Current Directions Biomed. Eng, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 470–474, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bergen T and Wittenberg T, “Stitching and surface reconstruction from endoscopic image sequences: A review of applications and methods,” IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 304–321, Jan. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Primus MJ et al. , “Segmentation of recorded endoscopic videos by detecting significant motion changes,” in Proc. 11th Int. Workshop Content-Based Multimedia Indexing, Jun. 2013, pp. 223–228. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Byrnes PD and Higgins WE, “A system for endobronchial-video analysis,” Proc. SPIE, vol. 10135, pp. 101351Q-1–101351Q-9, Feb. 2017. [Google Scholar]