Abstract

Objective:

The present study aimed to clarify the circumstances under which activity restriction (AR) is associated with depressive symptoms among patients with osteoarthritis (OA) and their spouses.

Method:

A total of 220 older adults with OA and their caregiving spouses participated in the study. The actor–partner interdependence model (APIM) was used to examine the associations between AR stemming from patients’ OA and the depressive symptoms of patients and spouses. The potential moderating role of marital satisfaction also was examined.

Results:

After accounting for pain severity, health, and life stress of both patients with OA and spouses, higher AR was associated with more depressive symptoms for both patients and spouses. In regard to partner effects, patients whose spouse had higher AR reported more depressive symptoms. In addition, the association of spouses’ and patients’ AR and their own depressive symptoms was moderated by their marital satisfaction. For both patients and spouses, the associations between their own AR and depressive symptoms were weaker for those with higher levels of marital satisfaction compared with those with lower levels of marital satisfaction.

Discussion:

This pattern of findings highlights the dyadic implications of AR and the vital role of marital satisfaction in the context of chronic illness.

Keywords: arthritis, depression, activity restriction, marital satisfaction, dyadic analysis

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a musculoskeletal disease characterized by chronic pain and physical disability. OA is known to have a major impact on patient functioning and independence, with both symptoms and disability becoming more prevalent with increasing age (Tait, Chibnall, & Krause, 1990). Given its chronic nature and debilitating physical effects, informal care plays a major role in OA patient care (Fekete, Stephens, Druley, & Greene, 2006). For many people with OA, the spouse becomes the main source of assistance with daily activities. Recent literature affirms that patients and spouses face this illness together, both making adjustments to their lifestyles to accommodate symptoms and limitations associated with OA (Berg & Upchurch, 2007; Williamson, 2000).

Prior studies have indicated that OA often results in activity restriction (AR) for both patients and their spouses (Benyamini & Lomranz, 2004; Williamson & Schulz, 1992). AR indicates the extent to which normal or routine activities are restricted due to physical illness such as pain (Williamson & Schulz, 1992). It is known that AR contributes to decreased emotional well-being and increased psychological distress for couples (Mausbach et al., 2011; Neiboer et al., 1998; Williamson, 2000). Although the associations between AR and depressive symptoms have been examined, scholars have rarely examined relationship variables (e.g., marital satisfaction) that could moderate the association between AR and depressive symptoms.

Using the actor–partner interdependence model (APIM; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006), the current study examined the association between AR from patients’ arthritis and patients’ own depressive symptoms as well as those of their spouse. Furthermore, we examined marital satisfaction as a moderator of the association between AR and depressive symptoms of patients and their spouses. Investigating these questions could identify conditions under which depression develops in couples who experience AR from a chronic illness such as OA.

The AR model of depressed affect (Williamson, 2000) proposes that the extent to which normal life activities are restricted by life stressors or illness accounts for the increase in depressive symptoms of patients. This model has been consistently supported in studies of people with physical disability or illness, including those with OA (Mausbach et al., 2011; Neiboer et al., 1998).

There is growing evidence that the health conditions or stressors experienced by a married older individual have important implications for his or her partner’s well-being (Berg & Upchurch, 2007; Wilson-Genderson, Pruchno, & Cartwright, 2008). In a longitudinal study of couples in which one spouse had end-stage renal disease, Pruchno, Wilson-Genderson, and Cartwright (2009) found that declines in patients’ self-rated health were significantly associated with an increase in spouses’ depressive symptoms. This cross-partner effect also was observed in reverse; a spouse’s caregiving burden was found to be linked not only to his or her own well-being, but to that of a spouse who had end-stage renal disease (Wilson-Genderson et al., 2008). Similarly, AR, which reduces enjoyable activities that a couple may do together, may be linked to the well-being of the spouse.

In the context of physical illness, marital satisfaction is considered beneficial for the mental health of patients, as it can buffer or attenuate effects of stress (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001). Consistent with this view, scholars have investigated the moderating role of marital quality between physical health and depressed affect among older adults with physical illness. For example, Tower and Kasl (1995) found that higher marital closeness buffered the negative impact of one’s own frailty and financial strain on depressive symptoms. In addition, Bookwala and Franks (2005) found that poor marital quality such as higher marital disagreement exacerbates the negative effects of physical disability on symptoms of depression.

In a satisfying marriage, patients may rely on their spouses or have better emotional support from their spouses, which can lessen the deleterious effects of AR on their depressive symptoms. Thus, it is expected that patients with OA may benefit from having a satisfying marital relationship in the midst of dealing with AR. Similarly, a satisfying marital relationship could benefit the spouses of patients by helping them minimize the stress resulting from their partner’s illness. Therefore, in this study, we hypothesized that high marital satisfaction would buffer the negative effects of AR on the depressive symptoms of patients with OA as well as their spouses.

Aside from the effects of AR, additional demographic, health, and social factors have been found to be associated with depressive symptoms in older adults. Personal factors (i.e., age and education), self-rated health, severity of illness, severity of pain, receipt of caregiver assistance with activities of daily living (ADL), and the number of stressors both members of the dyad experience have been found to contribute to depressive symptoms (Cano, Weisberg, & Gallagher, 2000; Kraaij & de Wilde, 2001).Thus, we included these variables as covariates in the models testing our hypotheses.

The goal of this investigation was to examine the interdependent experiences of patients with OA and their spouses using marital satisfaction as a moderator. It was hypothesized that patients’ and spouses’ AR would be associated with their own depressive symptoms (Hypothesis 1). Furthermore, we hypothesized that one’s own marital satisfaction would moderate the association between self-reported AR and depressive symptoms for both patients and spouses. Specifically, we expected that the linkage between AR and depressive symptoms would be weaker for patients and spouses in a satisfying marriage than for those in a less satisfying marriage (i.e., actor effect; Hypothesis 2).

Similarly, we hypothesized that one’s own marital satisfaction would moderate the link between partner-reported AR and depressive symptoms for both patients and spouses (i.e., partner effects; Hypothesis 3). Given the buffering role of marital satisfaction reported in the literature, we expected that the association between partner’s AR and their own depressive symptoms would be weaker for patients and spouses with higher marital satisfaction when compared with their counterparts in less satisfying marriages.

Method

Participants

This study used baseline data from a psychosocial intervention study of older adults with lower extremity OA and their caregiving spouses. Participants were recruited from rheumatology clinics affiliated with the University of Pittsburgh. To be eligible for the study, patients with OA had to be 50 years of age or older, married, and diagnosed with OA of the hip, knee, or spine. Additional criteria were that the patient had experienced pain of at least moderate intensity on most days over the past month, had difficulty with at least one instrumental activity of daily living, and had received assistance from his or her spouse with at least one instrumental activity of daily living.

Of the 1,145 couples who were interested in participating, 883 were ineligible. The three most common reasons for ineligibility were that the patient was unmarried or not living with his or her spouse (n = 420, 48%), had a comorbid diagnosis of fibromyalgia or rheumatoid arthritis (n = 141, 16%), or had upper extremity OA only (n = 131, 15%). Of the 262 eligible couples, 42 (16%) couples had missing scores on the independent or dependent measures for the current investigation, and were eliminated from the sample. Therefore, 220 participants were available for this investigation. When we tested the key difference between the 42 couples who had missing scores and the 220 couples, there was no statistical difference in terms of age, gender, and education. The majority of OA patients in this study were female (n = 163, 74%). The average age of patients was 68.84 years (SD = 7.62), and the average age of spouses was 69.6 years (SD = 8.18). Most of the sample was White (93%). Couples had been married for an average of 41 years (SD = 13.04), and patients reported having OA for 15.8 years on average (SD = 11.4).

Measures

Depressive symptoms.

Depressive symptoms were assessed with a 10-item version of the Centers for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), an internally reliable and valid measure of depressive symptomatology (Andresen, Malmgren, Carter, & Patrick, 1994). Shortened versions of the CES-D have been found to be highly correlated with the full scale (r = .96) in previous studies (Shrout & Yager, 1989). Participants reported how often they experienced specific symptoms during the past week, on a scale from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most of the time). Higher scores reflected more depressive symptoms. A score of 10 on this short version of the CES-D is generally believed to indicate risk for clinical depression among older adults (Andresen et al., 1994). Twenty-one percent (n = 92) of participants received scores above 10. Cronbach’s alpha was .78 for patients and .82 for spouses. We considered the possibility that two of the CES-D items (e.g., I could not get going, I felt that everything I did was an effort) might overlap with some of the items of Activity Restriction Scale (ARS). We re-ran our analyses without these two items and found results that were identical to the pattern observed with the full scale, so we kept the original 10 items.

Marital satisfaction.

Patients with OA and their spouses were asked to report their level of marital satisfaction using the Marital Adjustment Test (MAT; Locke & Wallace, 1959). This 15-item measure includes questions about general level of happiness, level of agreement on a number of issues, and ways of handling disagreements. On the MAT, higher scores are associated with better marital satisfaction, with scores below 100 indicating distress in the marriage (Locke & Wallace, 1959). The mean marital satisfaction score was 118.76 for patients (SD = 26.02) and 119.91 (SD = 24.88) for spouses. The average levels of marital satisfaction in the present sample were similar to those reported in other community-based samples (e.g., Crane, Allgood, Larson, & Griffin, 1990). The alpha for the measure was .77 for patients with OA and .79 for spouses.

AR.

Patients with OA and their spouses each indicated the extent to which eight areas of activity (e.g., socializing, community activities, going out for dinner, traveling, hobbies, recreational activities) were restricted by the patient’s OA on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much) using the ARS (Williamson & Schulz, 1992). The mean score on the ARS was 14.27 (SD = 5.32) for patients and 12.17 (SD = 4.58) for spouses (see Table 1). The average levels of AR in the present sample were similar to those reported in other studies (e.g., Williamson, 2000; Williamson & Schulz, 1992). The alpha for the measure was .85 for patients and .81 for spouses.

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations Between Covariates and Depressive Symptoms of Patients and Spouses.

| Variables | M (SD)/% | Patient’s depressive symptoms | Spouse’s depressive symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient’s age | 68.61 (7.57) | −.036 | −.045 |

| Patient’s gender (female) | 73.6 | −.049 | .145* |

| Patient’s education (years) | 14.48 (1.65) | −.129 | −.171* |

| Patient’s health | 3.04 (0.99) | −.405** | −.175** |

| Patient’s pain | 3.08 (0.77) | −.299 | .048 |

| Patient’s ADLa | 20.92 (3.42) | −.208 | −.160* |

| Patient’s recent life events | 1.86 (1.76) | .193** | .144* |

| Spouse’s age | 69.52 (7.48) | −.05 | −.09 |

| Spouse’s gender (female) | 26.4 | −.14* | −.06 |

| Spouse’s education | 14.45 (2.16) | −.146* | −.071 |

| Spouse’s healthb | 3.29 (1.00) | −.309** | −.128 |

| Spouse’s pain | 3.51 (0.75) | .076 | .210** |

| Spouse’s ADL | 18.52 (4.61) | .055 | .131 |

| Spouse’s recent life events | 1.7 (1.68) | .351** | −.023 |

Note. N = 220 dyads. ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; PADL = personal activities of daily living.

aADL indicates assistance to patient’s IADL and PADL.

bHealth was rated from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent).

*p < .05.

**p < .01.

***p < .001.

Demographic information.

Patients and spouses reported their age, gender (0 = female), and years of education (highest grade in school or years of college completed). Subjects also rated their physical health on a scale of 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent).

Pain severity.

Both patients and their spouses rated patients’ overall arthritis pain in the past month using a single item on a scale of 1 (very mild) to 5 (extremely severe). The mean scores on pain severity were 3.08 (SD = 0.77) for patients, and 3.51 (SD = 0.75) for spouses (Table 1).

Assistance for patients with OA (instrumental activities of daily living [IADL] and personal activities of daily living [PADL]).

Both patients and their spouses reported how much the spouse assisted with patients’ IADLs (four items; Lawton & Brody, 1969) and PADLs (four items; Lawton & Brody, 1969) on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). We combined these two subscales to indicate the assistance for patients with OA. The mean scores were 20.92 (SD = 3.43) for patients, and 18.52 (SD = 4.62) for spouses (see Table 1).

Recent life events.

Patients and their spouses indicated the number of stressful life events they had experienced within the past 6 months. The measure was adapted from the Elders Life Stress Inventory (ELSI; Aldwin, 1991) and the Cardiovascular Health Study (Fried et al., 1991). For the purpose of the study, 10 types of stressful life event items (e.g., moving, death of close friends) were summed, so that higher scores reflect more stressful life events. The mean score for stressful life events was 1.86 (SD = 1.76) for patients and 1.70 (SD = 1.68) for spouses (Table 1).

Analysis Plan

First, we ran t tests to compare patient and spouse reports on key outcomes as well as predictors. We then estimated bivariate associations between potential covariates and depressive symptoms (patient and spouse). The following variables were found to be associated with depressive symptoms of respective patient and spouse (see Table 1) and so were included in the analysis: gender, education, pain severity, self-rated health, assistance of ADL (i.e., sum scores of IADL and PADL), pain severity, and recent life events. The age of participants did not have significant associations with depressive symptoms, so age was not included in our analyses. As control variables that are not associated with a dependent variable may generate spurious associations between variables (Rovine, von Eye, & Wood, 1988), we included all variables identified in the previous step and then removed non-significant (p < .05) control variables sequentially starting with the highest p value, until only significant control variables remained.

To test our hypotheses, we first estimated how an individual’s AR relates to his or her own depressive symptoms and to his or her spouse’s depressive symptoms. These effects are addressed by the APIM (Kenny et al., 2006). Kenny and his colleagues (Kenny & Acitelli, 1996; Kenny et al., 2006) have proposed using APIM when dyads are the unit of analysis to explicitly examine potential mutual influences within dyads and also to account for interdependence within couples. This model tests whether a person’s scores on an independent variable affect his or her own dependent variable scores (i.e., actor effect) and his or her partner’s dependent variable score (i.e., the partner effect). In examining our hypothesis within the APIM framework, we used multilevel modeling (MLM) with PROC MIXED in SAS.

To distinguish whether the actor and partner effect differed by role (i.e., patient vs. spouse), we included social role (1 = patient, 0 = spouse) in our interaction terms. This determines whether an effect is unique to spouses or patients or if the effect applies to both partners equally. To test Hypotheses 2 and 3, we included each participant’s marital satisfaction as a moderator variable. As with covariates, we started the model with all variables and then removed non-significant interaction and presented the parsimonious model that only includes significant relationships.

Results

Paired Sample t Tests

In terms of AR, there were significant differences between patients and spouses, t(219) = 5.607, p < .001. That is, patients reported higher AR compared with spouses. In addition, we found that patients reported much higher depressive symptoms (M = 6.65, SD = 4.76) than spouses (M = 5.16, SD = 4.72, p < .001).

AR and Depressive Symptoms

Results of multilevel models that included AR and depressive symptoms are shown in Tables 2 and 3. For easier interpretation, we present both the unstandardized and standardized coefficients. We also present trimmed models instead of full models including all the variables (however, the full model table is available upon request).

Table 2.

Mixed Model Predicting Depressive Symptoms From Actor AR and Partner AR.

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | B (SE) | p | β | B (SE) | p | β |

| Patient | 7.88 (.83) | <.0001 | 8.23 (.83) | <.0001 | ||

| Spouse | 4.30 (.42) | <.0001 | 4.31 (.42) | <.0001 | ||

| Patient × Actor AR | 0.274 (.06) | <.0001 | .30 | 0.22 (.06) | <.0001 | .24 |

| Spouse × Actor AR | 0.217 (.06) | <.001 | .21 | 0.229 (.06) | <.0001 | .22 |

| Patient × Partner AR | 0.149 (.06) | .02 | .14 | |||

| Spouse × Partner AR | ||||||

| Covariates | ||||||

| Patient × Gender | −1.32 (.62) | .03 | −.14 | −1.43 (.62) | .021 | −.15 |

| Spouse × Gender | ||||||

| Patient × Education | ||||||

| Spouse × Education | ||||||

| Patient × ADL | ||||||

| Spouse × ADL | ||||||

| Patient × Self-rated health | −1.47 (.32) | <.001 | −.31 | −1.432 (.617) | <.0001 | −.29 |

| Spouse × Self-rated health | −1.16 (.29) | <.001 | −.24 | −1.07 (.29) | <.001 | −.23 |

| Patient × Pain severity | ||||||

| Spouse × Pain severity | ||||||

| Patient × RLE | ||||||

| Spouse × RLE | 0.71 (.17) | <.001 | .25 | 0.72 (.17) | <.0001 | .25 |

| AIC | 2,494.7 | 2,488.3 | ||||

| BIC | 2,504.9 | 2,504.5 | ||||

Note. N = 220 dyads. Parameter estimates are fixed effects. Non-significant effects were trimmed from the final model in both Model 1 and Model 2. AR = activity restriction; ADL = assistance with patient instrumental and personal activities of daily living; RLE = indicates recent life events; AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion.

Table 3.

Mixed Model Predicting Depressive Symptoms from AR and MS.

| Model 1 |

Model 2 (trimmed) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | B (SE) | p | β | B (SE) | p | β |

| Patient | 7.28 (.85) | <.0001 | 6.37 (.27) | <.0001 | ||

| Spouse | 3.35 (.87) | <.0001 | 4.17 (.40) | <.0001 | ||

| Patient × Actor AR | 0.167(.06) | <.01 | .18 | 0.21 (.06) | <.001 | .23 |

| Spouse × Actor AR | 0.123 (.07) | .03 | .12 | 0.12 (.06) | .06 | .12 |

| Patient × Partner AR | 0.128 (.06) | .06 | .12 | 0.136 (.05) | .03 | .13 |

| Spouse × Partner AR | 0.052 (.05) | .38 | .06 | |||

| Patient × MS | −0.044 (.01) | <.0001 | −.24 | −0.04 (.01) | .0001 | −.22 |

| Spouse × MS | −0.059 (.01) | <.0001 | −.31 | −0.05 (.01) | <.0001 | −.26 |

| Patient × Actor AR × MS | −0.002 (.001) | .31 | −.06 | −0.003 (.001) | .016 | −.09 |

| Spouse × Actor AR × MS | −0.005 (.002) | .029 | −.12 | −0.004 (.002) | .06 | −.09 |

| Patient × Partner AR × MS | −0.004 (.002) | .11 | −.10 | |||

| Spouse × Partner AR × MS | 0.002 (.002) | .19 | .06 | |||

| Covariates | ||||||

| Patient × Gender | −0.78 (.60) | .84 | −.08 | |||

| Spouse × Gender | 0.70 (.61) | .25 | −.07 | |||

| Patient × Education | −0.09 (.16) | .56 | −.03 | |||

| Spouse × Education | −0.16 (.12) | .21 | −.07 | |||

| Patient × ADL | −0.02 (.08) | .80 | −.01 | |||

| Spouse × ADL | 0.01 (.06) | .84 | .01 | |||

| Patient × Self-rated health | −1.22 (.31) | .0001 | −.25 | −1.31 (.29) | <.0001 | −.27 |

| Spouse × Self-rated health | −0.90 (.29) | .002 | −.19 | −0.84 (.28) | .004 | −.17 |

| Patient × Pain severity | 0.501 (.39) | .19 | .08 | |||

| Spouse × Pain severity | −0.81 (.41) | .047 | −.13 | |||

| Patient × Recent life events | 0.14 (.15) | .35 | .05 | |||

| Spouse × Recent life events | 0.68 (.16) | <.0001 | .12 | −0.65 (.16) | <.0001 | −.23 |

Note. N = 220 dyads. Parameter estimates are fixed effects. Table 1 includes covariates and predictors of interest. In Table 2, non-significant effects were trimmed and final significant covariates and predictors are presented. AR = activity restriction; MS = marital satisfaction; ADL = assistance with patient instrumental and personal activities of daily living.

Table 2 presents models examining the effect of Actor and Partner AR on depressive symptoms. As shown in Table 2 (Model 1), Hypothesis 1 was supported. Both patients and spouses who reported greater AR experienced more depressive symptoms (β = .274, p < .0001, for patients; β = .217, p < .001, for spouses). In the next step, partner AR was included (not shown in the table). As one of the partner effects (i.e., an interaction term; Spouse × Partner AR) was not significant, only significant two-way interaction (Patient × Partner AR) was included in the final model (see Model 2, Table 2). After including the partner AR effect, higher levels of AR of patients and spouses were still significantly associated with their own depressive symptoms (β = .22, .229, for patients and spouse; p < .0001 for both). Furthermore, Partner AR was significantly related to patients’ depressive symptoms (β = .149, p < .05), indicating that patients whose spouses reported higher AR also experienced higher depressive symptoms. In terms of covariates, we found that gender of the patients (i.e., women patients reported higher depressive symptoms), self-rated health of both patients and spouses, and higher levels of life stress of the spouses were significantly associated with depressive symptoms. Education, pain severity, and ADL limitations were not significantly associated with depressive symptoms (see Table 2).

AR, Marital Satisfaction, and Depressive Symptoms

Table 3 presents the effect of Actor and Partner AR and its interaction with marital satisfaction in predicting depressive symptoms. When partner AR effects were included, none of the two-way interactions including partner AR were significant (see Model 1, Table 3). Thus, we trimmed non-significant higher order interactions subsequently (Patient × Partner AR × MS, Spouse × Partner AR × MS). In the final model (Model 2, Table 3), we found significant two-way interactions (actor’s AR and marital satisfaction) for both patients and spouses, consistent with buffering hypothesis. That is, both patients and spouses with high AR levels reported higher depressive symptoms when their marital satisfaction was lower (β = −.003, p = .016 for patients, β = −.004, p = .06 for spouses; see Model 2, Table 3).

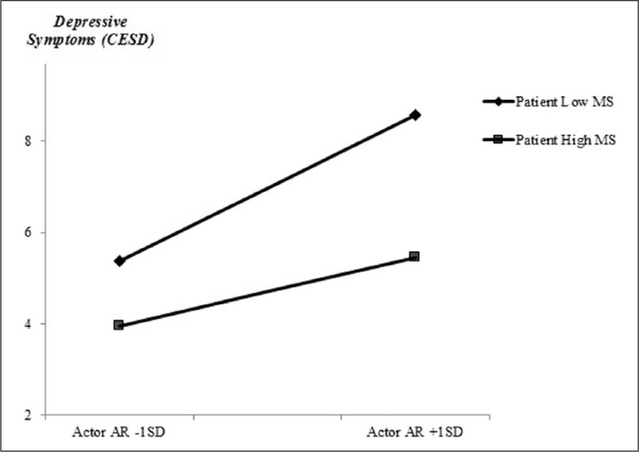

To illustrate the interaction, we show high and low levels of the moderator, defined as 1 SD above (M = 144.78) and 1 SD below (M = 93.90) the mean of marital satisfaction, respectively. First, we present the two-way interaction including actor AR at the level of marital satisfaction for patients (Figure 1). As seen in Figure 1, for patients, the association between actor AR and depressive symptoms was stronger when patients reported lower levels of marital satisfaction than when they reported having a satisfying marriage. That is, when marital satisfaction was lower (−1 SD), the level of patient AR was significantly associated with higher depressive symptoms. In contrast, when marital satisfaction was high (+1 SD), the level of patient AR was not associated with depressive symptoms.

Figure 1.

Patient’s depressive symptoms and interaction between actor AR (i.e., patient’s reported AR) and patient’s self-reported MS. Note. AR = activity restriction; MS = marital satisfaction.

This moderation effect was marginally significant for spouses (β = −.004, p = .06), indicating when marital satisfaction was lower (−1 SD), higher spouse AR was significantly associated with spouse’s own depressive symptoms, whereas lower spouse AR was not related to their depressive symptoms, when marital satisfaction was high (+1 SD). In terms of covariates, we found that self-rated health of both patients and spouses, and higher levels of recent life events of the spouses, were significantly associated with depressive symptoms. Education, pain severity, and ADL limitations were not significantly associated with depressive symptoms (see Table 3).

Discussion

This study extends prior research by indicating how AR resulting from patient’s OA has implications for the well-being of spouses as well as patients. In addition, by utilizing APIM framework, we were able to consider the association between the simultaneous experience of AR in both the patients with OA and their spouses with depressive symptoms. Furthermore, we also examined whether marital satisfaction moderates the association between one’s own AR and depressive symptoms for both patients and spouses.

AR and Depressive Symptoms

In support of our Hypothesis 1, which was to examine the association between AR and depressive symptoms, we found an association between a person’s greater AR and higher depressive symptoms for both patients with OA and their spouses. This indicates that spouses as well as patients experience more depressive symptoms when their own AR is high. Although previous studies have found a link between one’s own AR and depressive symptoms within each patient and spouse group, respectively (Neiboer et al., 1998; Williamson, Shaffer, & Schulz, 1998), they only considered the effects of AR on each person separately. However, it has rarely been demonstrated that partner AR is associated with one’s depressive symptoms. In this regard, extending prior findings, our results demonstrate the importance of marital context in understanding how a spouse’s AR is associated with the well-being of patients with OA.

We do not know from the current findings how spouses’ AR was communicated to patients, or the process through which the spouse’s AR was associated with higher depression in the patient. Several possibilities may account for these results. Patients may perceive an increase in AR on the part of the spouses and may have felt guilty. Alternatively, spouses’ increases in AR may lead to fewer pleasant activities for the couple, which affects depressive feelings for patients. Given that AR and depressive feelings were measured at the same time, we cannot rule out the possibility that depressed mood leads to increases in AR, or that there are reciprocal effects of AR and depressive feelings. Indeed, individuals with depressed mood often report reduced interest in social activities and limit their social lives (Dimidjian, Barrera, Martell, Munoz, & Lewinsohn, 2011). Future studies are needed to elucidate the process by which one’s own and one’s partner’s AR may influence depressive symptoms and vice versa.

Marital Satisfaction as a Moderator Between AR and Depressive Symptoms

Another important contribution of the current study is that marital satisfaction seems to buffer the negative effects of AR on the well-being of patients and spouses. Even after taking into account partner-reported AR, our findings support the buffering hypothesis, such that for spouses and patients who are in more satisfying marriages, the association between higher level of AR and depressive symptoms is not as strong as those in less satisfying marriages. Indeed, previous studies have postulated that the marital closeness moderates the relationship between illness-related stressors and depressive symptoms for patients and spouses (Bookwala & Franks, 2005; Leonard & Cano, 2006; Polenick, Martire, Hemphill, & Stephens, 2015).

Given that patients and spouses spend considerable time together as a result of illness management, higher marital satisfaction may protect both patients and spouses from feeling more depressed despite their vulnerable situation. A satisfying marital relationship, especially for spouses who are likely to provide care and instrumental support for the patients, may have helped them to cope with their stress resulting from AR. With regard to patients’ depressive symptoms, it is possible that an unpleasant marital climate exacerbates their distress resulting from AR or hinders receiving needed support from their spouses, which may contribute to their own depressive symptoms.

Although we cannot elucidate the specific process from our current findings by which a satisfying marriage protects patients with AR from feeling more depressed, previous studies have provided some inklings of this process. For example, studies have found that happily married couples are more likely to engage in dyadic coping (e.g., reciprocal interaction, open communication about illness and caregiving) or disclose their caregiving needs more explicitly while dealing with physical and mental disorders (Berg & Upchurch, 2007; Bodenmann, 2005). It may be that this type of openness and supportive caregiving contributes both to marital satisfaction and to containing the effects of AR on depressive symptoms. Indeed, studies have reported that happily married spouses may have chances to disclose their concerns related to AR to their spouses and receive needed support (Manne et al., 2007; Williamson et al., 1998).

There are several implications from this current study. First, instead of focusing just on a patient who has AR or other limitations due to a chronic illness, it is also important to consider the spouse’s AR, and depressive symptoms of both of them. Despite increasing recognition of the value of involving spouses in medical decisions and care, medical care remains primarily patient focused and its impact on spouses has not been considered. Second, it follows that intervention protocols for patients with OA may need to be expanded to include spouses. Many current interventions focus on improving depressive symptoms and quality of life for patients only. These interventions have not included or addressed the needs of spouses even though their daily lives and activities are also limited due to the illness of the patients with OA. A prior meta-analysis has indicated that dyadic interventions for chronic illness have potential to improve patients’ depressive symptoms (Martire, Schulz, Helgeson, Small, & Saghafi, 2010). Along these lines, dyadic interventions addressing the needs of caregivers (i.e., spouses) may also hold promise for improving their depressive symptoms. Finally, we need to learn more about the couple’s interactions that may buffer the impact of stressors, such as reduced activities of both patients and spouse on the well-being of both spouses and patients. Prior studies suggest that interventions that include couples and are designed to produce change in the partner’s interaction patterns may result in beneficial effects (Baucom, Whisman, & Paprocki, 2012). Future studies that could elucidate couples’ interaction patterns may provide fruitful directions to pursue for reducing their psychological stress resulting from physical illness.

Several limitations of this work should be noted. First, the use of a relatively homogeneous sample may restrict the generalizability of our findings. The couples examined here were mostly White and recruited from a single metropolitan area in the northeastern United States. In addition, the findings may not generalize to relationships in which the patient is receiving assistance from someone other than a spouse. A second issue is that the current study used a global measure of overall marital satisfaction. Future studies need to consider a more differentiated conceptual and measurement approach with regard to examining marital satisfaction. Third, although we controlled for other chronic conditions, we cannot rule out that AR was due in part to other conditions. Given that older adults are likely to have more than one health condition, future studies need to discern whether AR is mainly affected by OA or other chronic conditions. Finally, as noted, due to the cross-sectional nature of this study, it is impossible to rule out that people with more depressive symptoms experienced greater AR and less marital satisfaction, as each individual predictor can be confounded with psychological adjustment (Story & Bradbury, 2004). Therefore, it is vital to investigate these associations in future studies using a longitudinal design.

In conclusion, this study adds to the growing literature on the importance of the quality of marital relationships where one or both persons have chronic illnesses and limitations in everyday functioning as a result. Of course, marital quality is likely to have its effects on depressive symptoms and other outcomes through processes that contribute both to marital satisfaction and to more effective ways of managing the consequences of issues such as AR. Future research needs to identify what those helpful processes might be in a good marital relationship and, conversely, what features of lower quality marriages lead to poorer outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported in part by Grants HL65111-65112 and AG039412 awarded to Lynn M. Martire.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Aldwin M (1991). The Elders Life Stress Inventory (ELSI): Research and clinical applications In Keller PA & Heyman SR (Eds.), Innovations in clinical practice: A source book (Vol. 10, pp. 355–364). Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press. [Google Scholar]

- Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, & Patrick DL (1994). Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 10, 77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baucom DH, Whisman MA, & Paprocki C (2012). Couple-based interventions for psychopathology. Journal of Family Therapy, 34, 250–270. [Google Scholar]

- Benyamini Y, & Lomranz J (2004). The relationship between activity restriction and replacement with depressive symptoms among older adults. Psychology and Aging, 19, 362–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CA, & Upchurch R (2007). A developmental-contextual model of couples coping with chronic illness across the adult life span. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 920–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G (2005). Dyadic coping and its significance for marital functioning In Revenson TA, Kayser K, & Bodenmann G (Eds.), Decade of Behavior: Couples coping with stress: Emerging perspectives on dyadic coping (pp. 33–49). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bookwala J, & Franks MM (2005). Moderating role of marital quality in older adults’ depressed affect: Beyond the “main effects” model. Journal of Gerontology, 60, 338–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, Weisberg J, & Gallagher M (2000). Marital satisfaction and pain severity mediate the association between negative spouse responses to pain and depressive symptoms in a chronic pain patient sample. Pain Medicine, 1, 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, & Wills TA (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane DR, Allgood SM, Larson JH, & Griffin W (1990). Assessing marital quality with distressed and non-distressed couples: A comparison and equivalency table for three frequently used measures. Journal of Marriage and Family, 52, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Dimidjian S, Barrera M Jr., Martell C, Munoz RF, & Lewinsohn PM (2011). The origins and current status of behavioral activation treatments for depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7, 1–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete EM, Stephens MAP, Druley JA, & Greene KA (2006). Effects of spousal control and support on older adults’ recovery from knee surgery. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 302–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, & Acitelli LK (1996). Measuring similarity in couples. Journal of Family Psychology, 8, 417–431. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, & Cook WL (2006). The analysis of dyadic data. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, & Newton T (2001). Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 472–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraaij V, & de Wilde E (2001). Negative life events and depressive symptoms in the elderly: A life span perspective. Aging & Mental Health, 5, 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, & Brody EM (1969). Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist, 9, 179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard MT, & Cano A (2006). Pain affects spouses too: Personal experience with pain and catastrophizing as correlates of spouse distress. Pain, 126, 139–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke H, & Wallace K (1959). Short marital-adjustment and prediction tests: Their reliability and validity. Marriage and Family Living, 21, 251–255. [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, Norton TR, Ostroff J, Winkel G, Fox K, & Grana G (2007). Protective buffering and psychological distress among couples coping with breast cancer: The moderating role of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 380–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martire LM, Schulz R, Helgeson VS, Small BJ, & Saghafi EM (2010). Review and meta-analysis of couple-oriented interventions for chronic illness. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 40, 325–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Chattillion EA, Moore RC, Roepke SK, Depp CA, & Roesch S (2011). Activity restriction and depression in medical patients and their caregivers: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 31, 900–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neiboer AP, Schulz R, Matthews KA, Scheier MF, Ormel J, & Lindenberg SM (1998). Spousal caregivers’ activity restriction and depression: A model for changes over time. Social Science & Medicine, 47, 1361–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polenick CA, Martire LM, Hemphill RC, & Stephens MAP (2015). Effects of change in arthritis severity on spouse well-being: The moderating role of relationship closeness. Journal of Family Psychology, 29, 331–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruchno RA, Wilson-Genderson M, & Cartwright F (2009). Self-rated health and depressive symptoms in patients with end-stage renal disease and their spouses: A longitudinal dyadic analysis of late-life marriages. Journal of Gerontology, 64, 212–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 17, 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Rovine MJ, von Eye A, & Wood P (1988). The effect of low covariate criterion correlations on the analysis-of-covariance In Wegmen E (Ed.), Computer Science and Statistics: Proceedings of the 20th Symposium of the Interface (pp. 500–504). Alexandria, VA: American Statistical Association. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, & Yager TJ (1989). Reliability and validity of screening scales: Effects of reducing scale length. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 42, 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Story LB, & Bradbury TN (2004). Understanding marriage and stress: Essential questions and challenges. Clinical Psychology Review, 23(8), 1139–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait RC, Chibnall JT, & Krause S (1990). The Pain Disability Index: Psychometric properties. Pain, 40, 171–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tower RB, & Kasl SV (1995). Depressive symptoms across older spouses and the moderating effect of marital closeness. Psychology and Aging, 10, 625–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson GM (2000). Extending the activity restriction model of depressed affect: Evidence from a sample of breast cancer patients. Health Psychology, 14, 339–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson GM, & Schulz R (1992). Pain, activity restriction, and symptoms of depression among community-residing elderly. Journal of Gerontology, 47, 367–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson GM, Shaffer DR, & Schulz R (1998). Activity restriction and prior relationship history as contributors to mental health outcomes among middle-aged and older spousal caregivers. Health Psychology, 17, 152–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson-Genderson M, Pruchno RA, & Cartwright FP (2008). Effects of burden and satisfaction on psychological well-being of older ESRD patients and their spouses. Journal of Family Psychology, 23, 573–584. [Google Scholar]