Abstract

Amphibian embryos have long served as an ideal model for teratogenicity testing. While whole-mount embryo observations can be utilized, histological observation of teratogenic phenotypes provides a wealth of additional information that can lead to mechanistic insights. In this chapter, detailed protocols for two methods of sectioning embryos, as well as a guide for histological analysis are provided.

Keywords: Cryosectioning, Embryo, FETAX, Histology, Paraffin sectioning, Sectioning, Teratogen, Toxicology, Xenopus

1. Introduction

The frog embryo has served as an outstanding model organism for addressing significant problems in cell and developmental biology and has led to seminal discoveries in the areas of cell cycle regulation, cellular reprogramming and neural induction and patterning, axon pathfinding, and regeneration, to name a few (1,2). In addition, the amphibian model system has been a particularly important model for toxicology studies (3,4). Xenopus, the frog genus most commonly employed, lends itself to teratogenicity testing based on a number of key attributes. Thousands of fertilized eggs are routinely obtainable from a single mating and external fertilization allows experimenters to access the earliest stages of development. Embryos are large, with eggs being greater than one millimeter in diameter, permitting easy manipulation and observation. The long history of embryological studies at both the cellular and molecular level, and the availability of sequenced genomes of both Xenopus tropicalis and Xenopus laevis make comparative teratogenicity studies extremely powerful (1,2). Moreover, Xenopus embryos have been widely used as a tool for straightforward screening of potential teratogens, as described in the Frog Embryo Teratogenesis Assay: Xenopus (FETAX) (3,4). Although a widely used assay, FETAX relies on survival and pervasiveness of primarily structural abnormalities seen in live embryos to determine the presence and level of teratogenicity. However, many teratogens have more subtle phenotypes that are not discernible at the level of the whole embryo but rather require assessing changes at a finer resolution at the tissue and cellular level. Certain teratogenic effects can be detected much earlier with the aid of molecular markers assayed on the cellular level, thus making histological analysis an invaluable tool for more detailed observation and characterization of teratogenicity testing results.

In order to observe tissues in sufficient histological detail, the sections require some stain to provide contrast and detail, of which there are three general categories. Vital dyes (cresyl blue (5), hematoxylin and eosin (6), and others) are used to enhance tissue detail, while fluorescent stains (DAPI (7), and many more) are useful for their ability to target specific organelles and cellular features. However, assays for gene expression and molecular markers provide the most information given that alterations in gene expression often serve as early indicators of a teratogenic effect. In situ hybridization can be carried out in whole-mount as described by Sive et al. (1) to assess mRNA expression (see Note 1). Protein localization can be visualized with whole-mount immunocytochemistry as described by Lee et al. (8) or immunohistochemistry can be performed on sectioned samples according to Brown et al. (9). Fluorescent and chromogenic assays can be used in combination as described by Vize et al. (10).

Following the assay of choice, embryos must be sectioned using the most appropriate embedding medium and plane of sectioning. Embedding in paraffin is the most common method because it is straightforward and suitable for general brightfield microscopy as described by Sive et al. (1) and with our modifications detailed below. Embedding in plastic resin, detailed by Hausen and Riebesell (2) and Sive et al. (1), is a more complex method well-suited for analyzing intracellular morphology, but is not ideal for experiments requiring a large sample size due to its time intensive nature. In our experience, cryosectioning with embryos embedded in Tissue Freezing Medium, as carried out by Halleran et al. (11), has proven the most versatile sectioning method due to the wonderful preservation of cell and tissue morphology and superb performance under brightfield and fluorescence microscopy and imaging.

Following all assays and sectioning, the sections must be imaged appropriately for the assay used, the specifics of which will vary immensely across each specific assay, microscope, camera, and software system. Teratogenic phenotypes are best detected by comparing the histological morphology and gene expression of experimental embryos to normally developed embryos of the same stage. As a reference for normal histological morphology throughout development, Hausen and Riebesell’s The Early Development of Xenopus Laevis: An Atlas of the Histology (5) is an excellent resource. For more detailed analysis, cell morphology and tissue structure can be qualitatively scored in histological sections of experimental and control embryos, as performed by Bonfanti et al. (12), while quantitative analysis can include measurements of cell shape, size, number, and distribution, which can be easily obtained with image analysis tools, such as ImageJ (13). Gene expression can be qualitatively analyzed by comparing expression between experimental and control embryos and examining the sections for any ectopic or perturbed expression in the experimental sections, using Xenbase.org as reference for wild type gene expression information (2).

2. Materials

Histological observation is performed with a compound microscope and a high resolution camera coupled to a software system to capture images. For chromogenic assays and stains, brightfield imaging is appropriate. Assays including fluorescent color reactions can be visualized either with epifluorescence or on a confocal microscope. Confocal microscopy is generally preferred when available because background fluorescence from out of focus planes is greatly diminished in comparison to epifluorescence (14).

Be sure to adhere to all hazardous waste disposal guidelines and regulations when disposing of materials.

2.1. Paraffin Sectioning

Microtome.

Paraffin heater.

Paraffin oven.

Slide warmer.

Paraplast X-TRA® Paraffin (Sigma-Aldrich).

10x Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS): Fill a 1 L glass cylinder with 800 mL of ultrapure (18 mΩ) H2O. Add all of the dry ingredients: 2 g potassium chloride (KCl) [0.027 M], 80 g sodium chloride (NaCl) [1.37 M], 2.7 g potassium phosphate, monobasic (KH2PO4) [0.02 M], and 14.2 g sodium phosphate, dibasic (Na2HPO4 · 2H2O ) [0.08 M]. Cover the cylinder tightly with parafilm and invert until mixed. Bring the volume to 1 L with ultrapure H2O. Adjust pH to 7.4 with 1N NaOH or 1N HCl as needed. Pour the solution into glass bottles, autoclave on liquid cycle, and store at room temperature (see Note 2).

1x PBS: Add 100 mL 10x PBS to a 1 L glass cylinder. Bring volume to 1 L with ultrapure H2O. Cover the cylinder tightly with parafilm and invert several times to mix. Bring the pH to 7.4 with 1N NaOH or 1N HCl as appropriate. Pour the solution into glass bottles and store at room temperature.

100% ethanol.

100% xylene.

Embedding boats.

Mayer’s Albumin Adhesive: Separate the whites from the yolks of two large chicken eggs and place into a beaker and beat with a lab spatula to mix until the solution is homogenous. Transfer the beat egg whites to a 250 mL graduated cylinder and measure the volume. Add an equal volume of 100% glycerol to the cylinder. Cover with parafilm and invert to mix until homogenous. Measure the total volume and add 1/100th volume of 37% formaldehyde. Cover with parafilm and invert repeatedly until well mixed. Transfer the solution to a glass bottle and store at 4ºC.

Slides subbed with Mayer’s Albumin Adhesive: Place 1 drop of Mayer’s Albumin Adhesive onto the surface of a slide and spread evenly with a Kimwipe. Place the slide on a warmed hotplate inside a fume hood for 5–6 seconds, until the slide begins to stop steaming. There should be no brown residue on the slide as this means the coating has been burnt or applied incorrectly (Fig. 1A). Remove the slide from the hotplate and cool at room temperature. Slides can be coated a box at a time and then stored for future use.

CitriSolv™ (Fisher).

Fluoromount-G® (Southern Biotech).

Clear nail polish. We use Sally Hansen Xtreme Wear Invisible, although any hard finish clear nail polish should be acceptable.

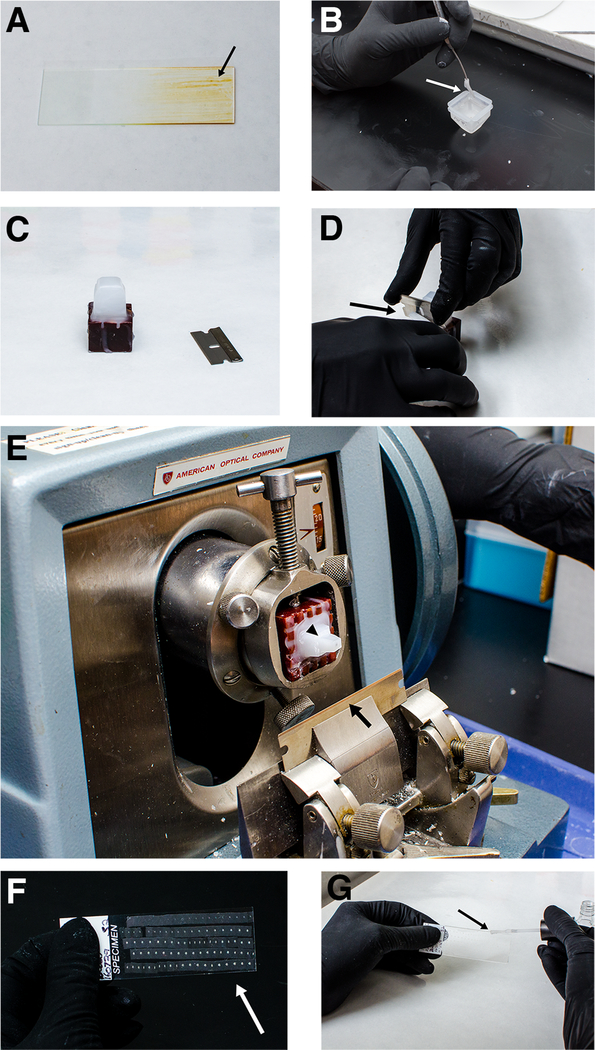

Figure 1. Paraffin sectioning.

A) Example of slide incorrectly subbed with Mayer’s albumin adhesive. Any brown color on the slide (arrow) is an indication that the adhesive has burned. (B) Paraffin has hardened too much to continue orienting (arrow). Re-melt the block and try again (see note 8). (C) Paraffin mounted to wooden block before being trimmed. (D) Carefully trim the paraffin block using a razor blade (arrow). (E) Block mounted to microtome. Note the 45º angle of the blade relative to the block (arrow). The paraffin block has been trimmed within 1–2 mm of the embryo and kept roughly square to yield good ribbons (arrow head). (F) Ribbons on a slide after drying. Note that the ribbons are straight and aligned well on the slide (arrow). (G) Applying nail polish border while coverslipping. Gently paint the nail polish around the border between the coverglass and slide on all sides (arrow).

2.2. Cryosectioning

Cryostat.

1.6 M Sucrose: Measure 27.36 g of sucrose into a 50 mL centrifuge tube. Fill to 50 mL with 1x PBS and mix until homogenous. Store at 4ºC.

Tissue Freezing Medium (TFM) (Triangle Biomedical Sciences).

Gelatin coated slides: Measure 0.15 g Knox brand gelatin into a 50 mL centrifuge tube. Fill to 50 mL with sterile ultrapure H2O. Invert to mix, then place the tube in a beaker of hot tap water until the gelatin is completely dissolved. Add 0.025 g chromium potassium sulfate (CrK(SO4)2) [1.8 mM] to the tube and dissolve completely by inverting the tube. Dip the slide into the tube while holding it by the frosted end. Remove the slide and place it frost-side down vertically in an open slide box to dry overnight. This can be done for an entire box of slides at a time. Cover the slides by carefully draping a large Kimwipe over them when the last slide is set to dry. Repeat this process the next day using freshly made gelatin dipping solution. Repeat a third time, again with fresh gelatin dipping solution.

3. Methods

3.1. Paraffin sectioning (based on Sive et al. (1))

Melt the paraffin either in a paraffin heater or glass beaker in a paraffin oven. This can take up to two hours, but one can proceed with the dehydration washes while the paraffin melts.

Begin with fixed embryos stored in glass vials filled with 1x PBS (see Note 3).

- Dehydrate the embryos with four washes as follows (see Note 4):

- Wash 15 min in a solution of 75 % 1X PBS / 25% ethanol.

- Wash 15 min in a solution of 50 % 1X PBS / 50% ethanol.

- Wash 15 min in a solution of 75 % 1X PBS / 25% ethanol.

- Wash 15 min in 100% ethanol.

Wash for 15 min in a solution of 50% ethanol / 50% xylene. Invert the tube gently to mix and incubate vertically. Do not nutate (see Note 5).

Wash for 15 min in 100% xylene. Invert the tube gently to mix and incubate vertically without nutation.

Transfer single embryos into individual embedding boats (see Note 6).

Turn on the paraffin oven and set the temperature to 60ºC.

Wash embryos in the boats with a solution of 50% xylene / 50% paraffin. It is not necessary to use a prepared solution, but rather one can simply fill the boat halfway with xylene, then fill to the top with paraffin. Then place the boat in a metal tray in the paraffin oven for 15 min (see Note 7).

Remove the xylene/paraffin solution from the boat and fill the boat with 100% paraffin. Incubate the boat in a metal tray in the paraffin oven for 2 h.

Carefully remove all of the paraffin from the boat and refill the boat with fresh paraffin. Incubate the boat in a metal tray in the paraffin oven for 2 h (see Note 8).

Remove the boat from the oven and again replace this paraffin with fresh paraffin.

The embryo must now be oriented for sectioning. For transverse sections along the anterior-posterior axis, manipulate the embryo with a metal probe to orient the head pointing straight down, and the tail straight up. This must be done quickly but gently as the paraffin in the bottom of the boat will solidify quickly (Fig. 1B). Make a mark on the block where the dorsal side of the embryo is located (see Note 9).

Allow the paraffin block containing an oriented embryo to harden at room temperature for at least 18 h.

Take the solid paraffin block and carefully peel away the plastic boat (see Note 10).

Mark the dorsal side of the embryo again, but directly on the paraffin block this time.

Affix the paraffin block to a wooden mount by melting the bottom (the widest part) and lower sides of the block flat with a flat spatula that has been heated in the flame of a Bunsen burner and then firmly press the melted paraffin into the wooden mounting block (Fig. 1C).

Trim the paraffin block with a sharp razor blade so that the embryo is only surrounded by about 1–2 mm of paraffin on each side. It is important to make the sides of the block as parallel as possible in order to prevent ribbon curling while sectioning (Fig. 1D).

Mount the block onto the microtome with the dorsal side pointing either left or right as this will produce transverse sections with the dorsal side of each section nicely oriented for later imaging.

Set the blade of the microtome so that the face of the block is at a 45º angle to the blade and perpendicular to the bench top (Fig. 1E).

Align the block with the blade and move the blade until it is 1–2 mm away from the face of the block.

Begin advancing the block and commence sectioning. Optimize sectioning conditions on the empty paraffin before the embryo is reached.

Mount a ribbon of paraffin sections onto a Mayer’s Albumin Adhesive subbed slide by spreading about 2 mL of sterile ultrapure H2O on the surface of the slide and then placing the ribbon into the water on the slide.

When the slide is full, place it on a slide warmer set to 40ºC and allow the slide to set overnight until all the water is completely evaporated and the paraffin lays flat on the slide (Fig. 1F).

Slides can be coverslipped after they have dried completely.

Submerge slides in CitriSolv™ for 3–5 min.

Remove from CitriSolv™ and blot the back and sides of each slide. Then submerge in sterile ultrapure H2O for 1 min to wash away residual CitriSolv™.

Blot the slides, then add 4 drops of Fluoromount-G® to the surface of the slide and apply coverglass, being careful to avoid bubbles.

Allow slides to air dry for 15–20 min.

Permanently seal the slides by applying clear nail polish in a border around the coverslip (Fig. 1G). Let the slides dry overnight.

Slides are now ready for imaging or storage.

3.2. Cryosectioning

Begin with fixed embryos stored in glass vials filled with 1x PBS.

- Cryoprotect the embryos by fixing in 1.6 M sucrose at 4ºC for at least 12 hours (see Note 11).

- Transfer up to 5 embryos to a 5 mL microcentrifuge tube, minimizing 1x PBS transfer.

- Remove as much transferred 1x PBS as possible using a P200 pipette.

- Fill the tube with 3 mL of 1.6 M sucrose.

- Wait for embryos to settle to the bottom of this dense solution. This may take 15–20 min.

- Store at 4ºC.

Turn on the cryostat and ensure that it cools down to approximately −20ºC while embryos are fixed in TFM.

Fix embryos in TFM by transferring a single embryo to a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube with minimal 1.6 M sucrose transfer. Remove as much transferred 1.6 M sucrose as possible using a P200 pipette. Fill the tube halfway with TFM ensuring that there are no air bubbles in the tube. Incubate for 2 hours at room temperature, then proceed to embedding or store at −20ºC for up to 2 weeks, or −80ºC indefinitely (see Note 12).

- Tape molds can begin to be prepared while embryos are TFM fixing (see Note 13).

- Take a 3–4 cm piece of colored lab tape (white tape makes orientation difficult) and make a cylinder out of it. This can be done by wrapping the non-adhesive side around the narrow end of a paintbrush (Fig. 2A). The diameter of the tape roll should be such that it fits between the smallest and next smallest rings of the metal chuck (Fig. 2B).

- Place the tape cylinder upright on the center of the chuck and surround it with a circle of TFM. The TFM should cover almost the entire chuck and surround the tape (Fig. 2C).

- Place the chuck with tape mold into the cryostat to allow the TFM to freeze. If the cryostat is equipped with a quick-freeze plate, use it to freeze the chuck (Fig. 2D).

- After the base of TFM is frozen solid, take the chuck out of the cryostat and slowly fill the cylinder of tape with TFM until it is about ¾ full (Fig. 2E). It is critical that there are no air bubbles in the TFM at this point. They will compromise the structure of the mold, potentially causing it to snap apart during sectioning.

- Return the chuck to the cryostat and allow the filled mold to freeze solid.

Embedding embryos in TFM can be tricky and must be done quickly and with precision.

Using a metal probe at room temperature, maneuver the embryo to the top of the tube. Retrieve the tape mold from the cryostat. Now scoop the embryo from the tube with the probe and hover it over the tape mold. Begin to squeeze TFM onto the embryo and allow it to fall from the probe into the tape mold.

As quickly and gently as possible, orient the embryo with the head pointing straight up and return the chuck to the cryostat quick-freeze plate. Make a mark on the frozen TFM on the base of the chuck to note the dorsal side of the embryo (Fig. 2F). Monitor the freezing process as the embryo may need to be held into place with the probe as it freezes.

If the top of the embryo is visible after the mold is frozen, add a small amount of TFM to the top of the mold and wait for it to freeze.

Carefully remove the tape surrounding the frozen TFM of the mold using cold forceps that have been stored in the cryostat (Fig. 2G).

Immediately apply a stabilizing ring of TFM to the mold where the tape was removed and freeze again. This ring should go up to at least ¼ of the height of the TFM cylinder containing the embryo (Fig. 2H).

Move the chuck to the microtome and lock it into position with the dorsal side of the embryo pointing straight up (Fig. 2I). Allow the embryo to equilibrate for 15–20 min before beginning sectioning. We typically set the blade to −19ºC and the chuck to −20ºC, but these setting can vary.

Move the blade to within 1–2 mm of the mold and begin sectioning. Use the empty part of the mold to optimize the anti-roll plate and ensure that sections of TFM are being cut without tearing or curling. This can be difficult and can vary depending on the temperature of the blade and chuck, the ambient temperature, humidity, and other environmental factors (see Notes 10 and 14).

When the embryo is reached, ensure that the section thickness is correct and the gelatin coated slide is labelled and ready.

Each section should be individually taken off the blade with a cold tool, such as a metal probe, forceps, broken glass Pasteur pipette, or small paintbrush, after lifting the anti-roll plate. After grabbing the section with the tool, place it immediately on the slide held in the other hand. A finger should be underneath the slide in the area one wishes to place the section. This keeps the slide warm enough to quickly melt the TFM section onto the slide (Fig. 2J).

Continue this process for each section. It is critical that the TFM from the following sections do not overlap with each other at all on the slide. This will prevent adherence between the section and slide, causing sections to fall off during coverslipping.

When the slide is filled, dry it at room temperature for at least 18 h before coverslipping.

While coverslipping slides, be extremely gentle when submerging the slides as sections may fall off. Begin by immersing slides in 1x PBS for 1 min.

Blot the slides and immerse in sterile ultrapure H2O for 1 min.

Blot the slides and submerge in clean 1x PBS for 5 min.

Blot the slides, then add 4 drops of Fluoromount-G® to the surface of the slide and apply coverglass, being careful to avoid bubbles.

Allow slides to air dry for 15–20 min.

Permanently seal the slides by applying clear nail polish in a border around the coverslip. Let the slides dry overnight.

Slides are now ready for imaging or storage.

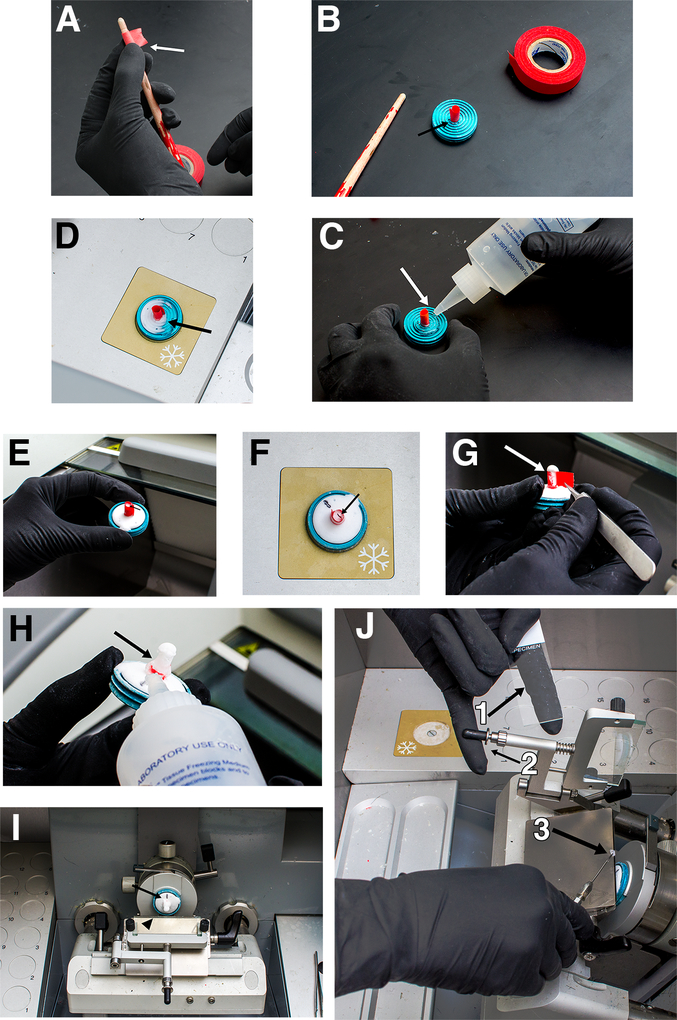

Figure 2. Cryosectioning.

(A) Making a tape mold. The tape is carefully wrapped around the paintbrush to make a cylinder (arrow). (B) The tape fits snuggly around the smallest rings of the chuck (arrow). (C) Applying TFM to the tape mold. The tape mold is surrounded with TFM, which covers almost the entire chuck (arrow). (D) Freezing the tape mold. TFM turns opaque white when frozen (arrow). (E) Tape mold filled with TFM. The mold should be filled ¾ full when the TFM is frozen (arrow). (F) Embryo being oriented in TFM. The embryo is placed with anterior up (arrow) and dorsal orientation is marked on the TFM on the chuck. (G) Removing the tape. The tape is gently peeled off of the frozen TFM using cold forceps (arrow). (H) Stabilizing ring of TFM after removing tape. Note the coverage of the stabilizing ring (arrow). (I) Chuck mounted in cryostat. The dorsal side as previously marked is pointing straight up (arrow). Note the angle of the blade (arrow head). (J) Picking up a frozen section. The slide is held with a finger underneath the area where the section will be placed to keep the slide sufficiently warm (arrow 1). The anti-roll plate is lifted using the slide-holding hand (arrow 2). The section is retrieved from the blade using a cold tool (arrow 3) and then quickly placed on the slide.

3.3. Identification and Analysis of Teratogenic Phenotypes in Histological Sections

While space precludes a description of all possible outcomes for every type of teratogenicity experiment, this chapter provides a general guide outlining the details of several common histological features at a variety of different stages that are often disrupted following treatment with a suspected teratogen. For comparative purposes, normal histology is nicely detailed in the work of Hausen and Riebesell (5), while data for gene expression is provided on Xenbase.org (2) and the references therein. We strongly urge experimenters to use in situ hybridization or immunocytochemistry to best analyze teratogenicity. For any tissue type or feature described below, an associated marker gene can be found for that particular structure in Xenbase.org (2). The use of molecular assays provides added detail, increased resolution, and earlier detection of teratogenic phenotypes. Although a wealth of additional, more specific, cell types can be assayed, investigating the following features in experimental samples will serve as an excellent start when assessing teratogenicity. All stages follow the standard Nieuwkoop and Faber staging guide for Xenopus (15) with histological features shown and described in Hausen and Riebesell (5).

Fine cell-blastula stage (St. 9): In an animal-vegetal section through the midline, the blastocoel roof (the animal cap) should extend across the majority of the animal pole and consist of an outer epithelial layer and an inner layer of two to three cells. Whereas the animal pole cells are more rounded with spaces in between, vegetal cells are larger, flatter and have extensive cell-cell contacts. The large blastocoel should not contain loose cells.

Early gastrula stage (St. 10): In a sagittal section through the midline, the blastocoel roof should consist of two distinct layers, an outer epithelial layer and an inner sensorial layer. The expansion of the blastocoel roof is more pronounced on the dorsal side. A clear blastopore groove is evident on the dorsal side with bottle cells near the blastopore groove.

Mid-gastrula stage (St. 11.5): A mid-sagittal section should reveal a large yolk plug vegetally, with bottle cells surrounding a ventral blastopore groove. Involution on the dorsal side extends approximately half way up the embryo with bottle cells defining the tip of the emerging, but very thin archenteron. Cells around the dorsal lip are tightly packed with no orderly arrangement. The animal cap (cells not underlain by mesendoderm) has now shrunk to half the length of early gastrula stages. Cells in the presumptive inner sensorial layer of the neuroectoderm become elongated. The blastocoel should be free of cellular material.

Neural plate stage (St. 14): In an anterior transverse section, the three germs layers and the structures to which they give rise are distinct. A single-cell layer of the neuroectoderm (dorsally) and epidermal neuroectoderm (laterally and ventrally) form the outer layer of the sectioned embryo. Interior to this is a sensorial layer that is a single layer for the epidermal layer and a thickened multicellular layer in the neural ectoderm. A central transverse section will show a nearly closed neural tube with bottle cells localized to the inside of the neural tube. The notochord should be visible at the dorsal midline directly below the neural tube and is flanked on both sides by the double-layered somitic mesoderm. The lateral mesoderm is also double-layered and is somewhat separated from the large ventral endodermal cells. The archenteron should be free of cellular material, with a single layer of cells comprising the archenteron roof.

Neural Tube Stage (St. 20): A mid-level transverse section should reveal a neural tube with elongated ventral floorplate cells and a clear central canal that is completely overlain by an epidermal sheet of cells. The notochord remains a delineated oval structure directly below the neural tube, while the presumptive somites are visible structures with elongated horizontal cells flanking both the neural tube and notochord. The somatic and splanchnic layers of the lateral plate mesoderm are distinguishable from each other and from the large cell, ventrally-positioned, endodermal cells.

Tail bud stage (St. 26): The tail bud is a particularly useful stage for analyzing teratogenicity, given that it is sufficiently early to detect early defects but late enough to analyze developing organ rudiments. An anterior transverse section through the presumptive eye region should reveal a largely elongated forebrain with a clear ventricular space and symmetric optic vesicles still attached at the ventral surface. More ventrally, loose head mesenchymal cells surround the stomodeum (mouth) vesicle, below which lie vertically elongated cement gland cells. A more posterior transverse section at the spinal cord level shows a roughly circular multicellular layered spinal cord with notochord present immediately ventral and well-delineated somites present ventro-laterally. The pronephric anlage are also visible as distinct oval structures just ventral to the somites.

Following tail bud stages, organogenesis and cell differentiation take place, with the cellular structures for virtually all organ systems now present. At these later stages, it is advisable to be familiar with the specific structure of interest and use tissue and organ specific marker genes to assess teratogenicity using histological atlases. Morphological differences can be identified by comparing experimental embryos to sibling control embryos (see Note 15). It is important to always have appropriate controls throughout each process.

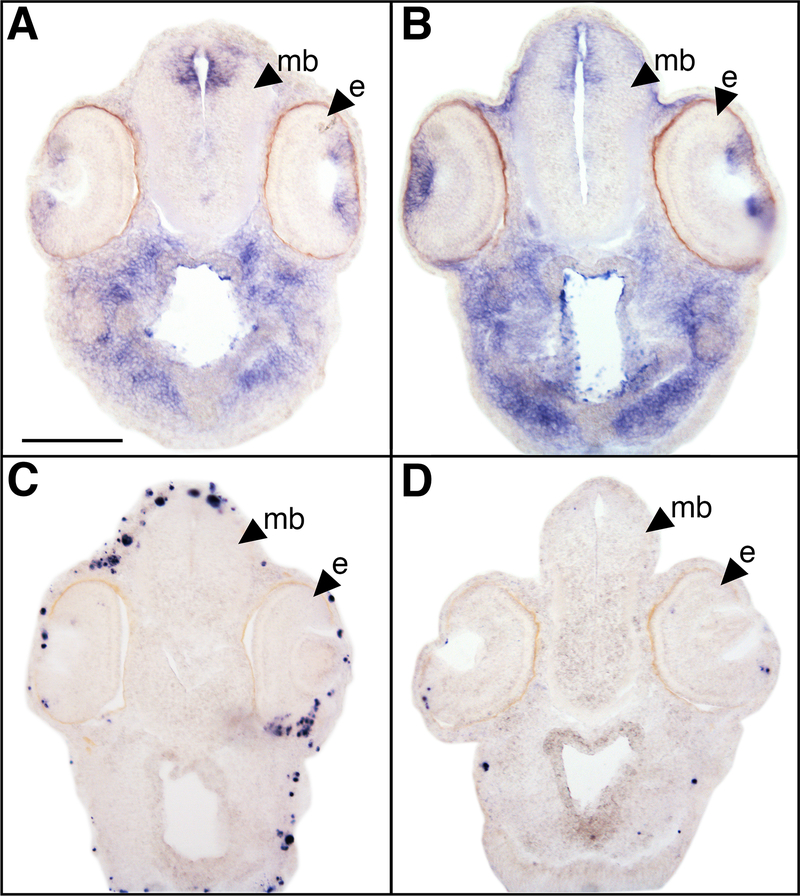

An example of histological analysis of stage 37 embryos using molecular markers and the above described cryosectioning method can be seen in Fig. 3.

Figure 3. Example of histological analysis following developmental mercury exposure.

Histological analysis of embryos exposed to 1 ppm MeHgCl and sibling control embryos. In situ hybridization shows proliferation-marker, xPCNA, expression (A, B) while TUNEL assay shows apoptotic cells (C, D). xPCNA expression appears mildly diminished in MeHgCl embryos (A) when compared with sibling control embryos (B) even though no morphological differences are observed in the histology. MeHgCl exposed embryos also show an apparent increase in apoptosis (C) when compared to sibling control embryos (D). Abbreviations: mb, midbrain; e, eye. Scale bar is 150 μm. Images courtesy of Ryan Huyck.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH (1R15HD077624–01 to MSS), NSF (1257895 to MSS), Howard Hughes Medical Institute Science Education Program Grant to the College of William and Mary, and the College of William and Mary Roy R. Charles Center Honors Fellowship to MEP.

Footnotes

While performing the assay, signal should be allowed to darken beyond what would be appropriate for whole-mount analysis because the signal will be noticeably weaker in sections.

Depending on the specific use, it may be best to sterilize only 10x PBS and not 1x PBS, or to sterilize only 1x PBS and not 10x PBS. Alternatively, autoclaving both 10x PBS and 1x PBS may be best.

If embryos are stored in 100% ethanol, the dehydration is not necessary and can be skipped.

Fill vials to the top with solution and nutate horizontally.

For all xylene washes, it is important to completely remove all xylene as residual xylene will make sectioning impossible.

Label embedding boats with Sharpie markers because xylene washes of many common lab markers.

This wash may be as long as 30 min, but no longer. Extended time in xylene makes sectioning more difficult, but it is essential to wait for the paraffin to melt completely at this step before proceeding.

Proceed with only one boat at a time for steps 11 and 12 as paraffin solidifies rapidly.

If the embryo is not properly oriented at this stage, the boat can be placed back in the oven to melt paraffin. Do not embed the embryo too close to the bottom of the boat, because the top of the block will be needed for optimizing the ribbon during the early stages of sectioning before reaching the tissue.

Sectioning is difficult procedure to describe, so it is best to watch someone demonstrate these techniques.

Embryos can be stored indefinitely in 1.6 M sucrose at 4ºC.

Best results are obtained from proceeding immediately to embedding and sectioning after fixing in TFM, rather than storing. If embryos need to be stored, it is best to keep them in either 1x PBS at 4ºC or 1.6 M sucrose at 4ºC.

TFM turns opaque white when it freezes.

One can section at a thickness greater than is desired for the tissue sections during this time in order to reach the embryo in less time, but remember to switch back to the correct thickness when the embryo is reached. Also, be sure to check that thinner sections do not tear or curl if the anti-roll plate is optimized with thicker sections.

Sibling refers to an embryo from the same mating as the experimental embryos that is reared normally and undergoes no experimentation.

References

- 1.Sive HL, Grainger RM, Harland RM (2000) Early development of Xenopus laevis. A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karpinka JB, Fortriede JD, Burns KA, James-Zorn C, Ponferrada VG, Lee J, Karimi K, Zorn AM, Vize PD (2015) Xenbase, the Xenopus model organism database: new virtualized system, data types and genomes. Nucleic Acids Research 43:D756–D763. Doi 10.1093/nar/gku956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dumont J, Schultz TW, Buchanan M, Kao G (1983) Frog Embryos Teratogensis Assay: Xenopus (FETAX) - A short-term assay applicable to complex environmental mixtures In: short-term bioassays anal. complex environ. mix. III. Plenum Press, New York, pp 394–405 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fort DJ, Paul RR (2002) Enhancing the predictive validity of frog embryo teratogenesis assay – Xenopus (FETAX). J. of Applied Toxicology 22:185–191. doi 10.1002/jat.848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hausen P, Riebesell M (1991) The early development of Xenopus laevis: An atlas of the histology. Springer-Verlag Telos, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischer AH, Jacobson KA, Rose J, Zeller R (2008) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue and cell sections. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 3:3–5. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kapuscinski J (1979) DAPI: a DNA-specific fluorescent probe. Biotech Histochem 70:220–233. doi: 10.3109/10520299509108199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee C, Kieserman E, Gray RS, et al. (2008) Whole-mount fluorescence immunocytochemistry on Xenopus embryos. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown DD, Martz SN, Binder O, et al. (2005) Tbx5 and Tbx20 act synergistically to control vertebrate heart morphogenesis. Development 132:553–563. doi: 10.1242/dev.01596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vize PD, McCoy KE, Zhou X (2009) Multichannel wholemount fluorescent and fluorescent/chromogenic in situ hybridization in Xenopus embryos. Nat Protoc 4:975–983. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halleran AD, Sehdev M, Rabe BA, et al. (2015) Characterization of tweety gene (ttyh1–3) expression in Xenopus laevis during embryonic development. Gene Expr Patterns 17:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2014.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonfanti P, Colombo A, Orsi F, et al. (2004) Comparative teratogenicity of Chlorpyrifos and Malathion on Xenopus laevis development. Aquat Toxicol 70:189–200. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2004.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schindelin J, Rueden CT, Hiner MC, Eliceiri KW (2015) The ImageJ ecosystem: an open platform for biomedical image analysis. Mol Reprod Dev 529:518–529. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White JG, Amos WB, Fordham M (1987) An evaluation of confocal versus conventional imaging of biological structures by fluorescence light microscopy. J Cell Biol 105:41–48. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.1.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nieuwkoop P FJ (1994) Normal Table of Xenopus Laevis (Daudin): A systematical & chronological survey of the development from the fertilized egg till the end of metamorphosis. Http://WwwXenbaseOrg/Anatomy/AlldevDo. doi: 10.1086/402265 [DOI] [Google Scholar]