Abstract

Rationale

The Epilepsy Bioinformatics Study for Antiepileptogenic Therapy (EpiBioS4Rx) Centre without walls is an NIH funded multicenter consortium. One of EpiBioS4Rx projects is a preclinical post-traumatic epileptogenesis biomarker study that involves three study sites: The University of Eastern Finland, Monash University (Melbourne) and the University of California Los Angeles. Our objective is to create a platform for evaluating biomarkers and testing new antiepileptogenic treatments for post-traumatic epilepsy (PTE) using the lateral fluid percussion injury (FPI) model in rats. As only 30–50% of rats with severe lateral FPI develop PTE by 6 months post-injury, prolonged video-EEG monitoring is crucial to identify animals with PTE. Our objective is to harmonize the surgical and data collection procedures, equipment, and data analysis for chronic EEG recording in order to phenotype PTE in this rat model across the three study sites.

Methods

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) was induced using lateral FPI in adult male Sprague-Dawley rats aged 11–12 weeks. Animals were divided into two cohorts: a) the long-term video-EEG follow-up cohort (Specific Aim 1), which was implanted with EEG electrodes within 24 h after the injury; and b) the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) follow-up cohort (Specific Aim 2), at 5 months after lateral FPI. Four cortical epidural screw electrodes (2 ipsilateral, 2 contralateral) and three intracerebral bipolar electrodes were implanted (septal CA1 and the dentate gyrus, layers II and VI of the perilesional cortex both anterior and posterior to the injury site). During the 7th post-TBI month, animals underwent 4 weeks of continuous video-EEG recordings to diagnose of PTE.

Results

All centers harmonized the induction of TBI and surgical procedures for the implantation of EEG recordings, utilizing 4 or more EEG recording channels to cover areas ipsilateral and contralateral to the brain injury, perilesional cortex and the hippocampus and dentate gyrus. Ground and reference screw electrodes were implanted. At all sites the minimum sampling rate was 512 Hz, utilizing a finite impulse response (FIR) and impedance below 10 KΩ through the entire recording. As part of the quality control criteria we avoided electrical noise, and monitoring changes in impedance over time and the appearance of noise on the recordings. To reduce electrical noise, we regularly checked the integrity of the cables, stability of the EEG recording cap and the appropriate connection of the electrodes with the cables. Following the pipeline presented in this article and after applying the quality control criteria to our EEG recordings all of the sites were successful to phenotype seizure in chronic EEG recordings of animals after TBI.

Discussion

Despite differences in video-EEG acquisition equipment used, the three centers were able to consistently phenotype seizures in the lateral fluid-percussion model applying the pipeline presented here. The harmonization of methodology will help to improve the rigor of preclinical research, improving reproducibility of pre-clinical research in the search of biomarkers and therapies to prevent antiepileptogenesis.

Keywords: Common data elements, Electroencephalogram, Post-traumatic epilepsy, Seizures, Traumatic brain injury

1. Introduction

Every 13 s a new person is diagnosed with epilepsy somewhere in the world, and in many cases structural damage like traumatic brain injury (TBI) is implicated as the primary cause of epileptogenesis (http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs999/en/). The risk of epileptogenesis varies with the severity of the TBI, being estimated at 2.1% for mild, 4.2% for moderate and 16.7% for severe TBI (Annegers et al., 1998; Lowenstein, 2009). Moreover, TBI is believed to be responsible for 15–20% of acquired epilepsy, and 5% of epilepsy overall (Herman, 2002; Lowenstein, 2009)

Over the past 15 years more than 40 hypothesis driven therapies with potential antiepileptogenic or disease modifying effects have been tested in animal models with various degrees of efficacy, but none of them have been successfully translated to the clinic (Galanopoulou et al., 2012; Pitkänen and Engel, 2014; Simonato et al., 2014). One factor hindering the translation of data from preclinical studies to the clinic has been the difficulty to reproduce the data in confirmatory preclinical studies, which relates to insufficient power in preclinical study designs (Landis et al., 2012). One of the approaches to overcome underpowered preclinical studies is to perform harmonized multicenter studies with large animal numbers, which is typically unachievable by a single laboratory (Lapinlampi et al., 2017).

The study of epileptogenesis in TBI experimental models is particularly challenging due to the slow progression of epileptogenesis, and the relatively low incidence of animals with epilepsy and low seizure frequency when compared to post-status epilepticus models (Pitkänen et al., 2007). These facts lead to requirements for long-duration continuous video electroencephalogram (vEEG) monitoring with long-term follow-up and a large sample size. Therefore, a major bottleneck to the development of anti-epileptogenic drugs is the time and resources required for chronic vEEG screening and analyses of seizures.

Here we harmonized EEG surgical and data collection procedures, equipment, and data analysis for EEG recordings in order to phenotype PTE in a rat model of TBI across three study sites of the NIH Funded Centre without Walls consortium, EpiBios4Rx. Our efforts outlined the common challenges and ways to address them, and resulted in standardized procedures, which provide a multicenter platform for a reliable seizure detection in a lateral FPI model.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study sites

Three sites from the international multicenter-based project EpiBioS4Rx (http://epibios.loni.usc.edu/) were involved in the standardization of lateral FPI model and post-injury monitoring protocols as part of the preclinical post-TBI biomarker project. These sites are The University of Eastern Finland (UEF, Kuopio, Finland), Melbourne, Australia (Monash University and The University of Melbourne), and The University of California Los Angeles (UCLA, California, USA).

2.2. Induction of lateral FPI

All procedures and data collection were harmonized by using common data elements (CDEs) and case report forms (CRFs). In all three study sites, adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (300–350 g) were used. In the present manuscript we will focus on the aspects of harmonization of vEEG-related procedures.

In UEF and Melbourne, rats were individually housed in a controlled environment (temperature 22 ± 1 °C; humidity 5060%; lights on from 07:00–19:00 h). In UCLA, the animals were housed in pairs under controlled environment (temperature 22 ± 1 °C; humidity 4070%; lights on from 06:00 to 18:00 h) until the surgery day. Food and water were provided ad libitum for the duration of the study in all the sites. In UEF, all animal procedures were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Provincial Government of The Southern Finland, and carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the European Community Council Directives 2010/63/EU. In Melbourne, animal procedures were approved by the Florey Animal Ethics Committee (ethics number 17–014 UM) in adherence to the Australian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes; and in UCLA, by the University of California Los Angeles Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol 2000–153).

The induction of the lateral FPI model was performed as described in detail by Ndode-Ekane et al. (2019; this Supplement). Briefly, under isoflurane anesthesia a 5 mm diameter craniotomy with a center co-ordinates of AP −4.5 mm and ML 2.5 mm from Bregma was performed in male rats at approximately 11 weeks of age. TBI was induced with a fluid percussion device equipped with a straight tip (AmScien Instruments, Model FP 302, Richmond, VA, USA in all centers) connected to a plastic female Luer-Lock attached into the craniotomy vertical to the surface of the skull. The details of the induction of lateral FPI are shown in Table 1. The pressure level was adjusted to produce moderate-severe TBI with an expected 20–30% post-impact mortality within the first 48 h (Liu et al., 2016a; Pitkänen and McIntosh, 2006; Reid et al., 2016; Shultz et al., 2015). A moderate-severe TBI was selected because it has been reported to induce PTE in 30% of the rodents (Brady et al., 2018; Kharatishvili et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2016b; Reid et al., 2016), which is similar to the incidence of PTE reported in patients with TBI (Frey, 2003; Englander et al., 2003b; Christensen et al., 2009b)

Table 1.

Lateral fluid percussion injury details.

| Center | Anesthesia | Craniotomy | Fluid-percussion device | Pressure level/ expected mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UEF | Induction isoflurane 5% – maintained 1.9% | Hand-held trephine (diameter 5 mm) Craniotomy center coordinates: AP −4.5 mm from the bregma; ML 2.5 mm; intact dura |

AmScience Instruments, Model FP 302, Richmond, VA, USA straight tip |

Adjusted to produce moderate-severe TBI with expected 20–30% post-impact mortality within the first 48 h (Pitkänen and McIntosh, 2006). |

| Melbourne | Induction isoflurane 5% – maintained 1.9% | Motorized drill. Diameter 5 mm center coordinates: AP −4.5 mm from the bregma; ML 2.5 mm; intact dura |

AmScience Instruments, Model FP 302, Richmond, VA, USA straight tip |

Adjusted to produce moderate-severe TBI with expected 20–30% post-impact mortality within the first 48 h (Pitkänen and McIntosh, 2006). |

| UCLA | Induction isoflurane 5% – maintained 1.5–2.0 % | Hand-held trephine Diameter 5 mm center coordinates: AP −4.5 mm from the bregma; ML 2.5 mm; intact dura |

AmScience Instruments, Model FP 302, Richmond, VA, USA straight tip |

Adjusted to produce moderate-severe TBI with expected 20–30% post-impact mortality within the first 48 h (Pitkänen and McIntosh, 2006). |

UEF, University of Eastern Finland; UCLA, University of California Los Angeles; TBI, traumatic brain injury. AP, Anterior – Posterior. ML, Medial – Lateral.

2.3. Harmonization of electrode implantation

At the three sites, implantation of EEG recording electrodes was performed according to the needs of the two specific aims. For specific Aim 1 (long-term video-EEG follow-up), electrodes were implanted right after FPI (UEF, UCLA) or within 24 h after FPI (Melbourne). For Specific Aim 2 (long-term MRI follow-up), rats were implanted with EEG recording electrodes 5 months after the FPI (see Ekolle Ndode-Ekane et al., 2019; Santana-Gomez et al., 2019 in This Supplement). Briefly, rats were anesthetized with isofluorane and surgery was performed under aseptic technique. Fur was shaved from the skin above the planned craniotomy and a single midline incision was made on the scalp. For Specific Aim 1 six burr holes were drilled through the skull without penetrating the dura. Six stainless steel epidural screw recording electrodes (UEF and Melbourne: EM12/20/SPC, Plastics One Inc; UCLA: F000CE096, J.I. Morris Co) were screwed into the burr hole. Ground and reference electrodes stainless steel epidural screw electrodes were implanted above the cerebellum were implanted above in the occipital bone the cerebellum, ipsilateral and contralateral to the craniotomy, respectively. In addition, three bipolar intracerebral tungsten microelectrodes (EM12 T/5–2TW/SP) were placed in the anterior and posterior perilesional cortex, targeting the cortical layers II and VI, and in the septal hippocampus, targeting CA1 and the dentate gyrus according the coordinates of the rat brain atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 1986)(Table 2 and Fig. 1A).For Aim 1, The location of electrodes was confirmed by histological analysis in a small cohort of animals before the start of the experiments. As lateral FPI results in cortical atrophy over the time (Immonen et al., 2009), in Specific Aim 2 the coordinates for two perilesional and 1 hippocampal microelectrodes were adjusted according to the 5-month T2-weigted coronal MRI images to optimize their locations. Further confirmation of the location of the intra-cerebral electrodes was confirmed after postmortem analysis of the tissue for both aims (Table 2, Fig. 2B; Santana-Gomez et al., 2019 in this Supplement). The recording electrodes were fixed in position by applying with dental acrylate (UEF Selectaplus powder #10009210 and liquid #D10009102, DeguDent, Germany; Melbourne, Self-cure powder VX-SC1000GVD5 and liquid VX-SC1000GMLLQ, Vertex, Australia, UCLA, SNAP Liquid #P16–02-65; SNAP Powder #P16–02-60, Pearson Dental, USA).

Table 2.

Locations of epidural and intracerebral electrodes for the three sites.

| Centre | How long after FPI? | Electrode Type | C3 | C4 | O1 | O2 | Electrode Type | A1, A3 | H1, H3 | Po1, Po3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UEF | After the righting reflex returned and 5 months after FPI | Stainless steel epidural screw (EM12/20/SPC, Plastics One Inc.) | Ipsilateral Frontoparietal (AP: −1.7; ML: −2.5) | Contralateral Frontoparietal (AP: 1.7; ML: −2.5) | Ipsilateral Occipital (AP: −7. 6; ML: left 2.5) | Contralateral Occipital (AP: −7.6; ML: right 2.5) | Bipolar intracerebral tungsten .002" twisted electrode (EM12 T/5–2TW/SP, Plastics One Inc.) | Ipsilateral anterior intracortical (AP: −1.72; ML: −4.0; DV: −1.8) | Ipsilateral intrahippocampal (AP: −3.0; ML: −1.4; DV: −3.6) | Ipsilateral posterior intracortical (AP: −7.56; ML: −2.5; DV: −1.75) |

| Melbourne | 24 h and 5 months after FPI | Stainless steel epidural screw (EM12/20/SPC, Plastics One Inc.) | Ipsilateral Frontoparietal (AP: −1.7; ML: −2.5) | Contralateral Frontoparietal (AP: 1.7; ML: −2.5) | Ipsilateral Occipital (AP: −7. 6; ML: left 2.5) | Contralateral Occipital (AP: −7.6; ML: right 2.5) | Bipolar intracerebral tungsten .002" twisted electrode (EM12 T/5–2TW/SP, Plastics One Inc.) | Ipsilateral anterior intracortical (AP: −1.72; ML: −4.0; DV: −1.8) | Ipsilateral intrahippocampal (AP: −3.0; ML: −1.4; DV: −3.6) | Ipsilateral posterior intracortical (AP: −7.56; ML: −2.5; DV: −1.75) |

| UCLA | After the righting reflex returned and 5 months after FPI | Stainless steel epidural screw (F000CE096, J.I. MORRIS CO) | Ipsilateral Frontoparietal (AP: −1.72; ML: left 2.5) | Contralateral Frontoparietal (AP: 1.72; ML: right 2.5) | Ipsilateral Occipital (AP: −7.56; ML: left 2.5) | Contralateral Occipital (AP: −7.56; ML: right 2.5) | Bipolar intracerebral tungsten .002" twisted electrode (EM12 T/5–2TW/SP, Plastics One Inc.) | Ipsilateral anterior intracortical (AP: −1.72; ML: −4.0; DV: −1.8) | Ipsilateral intrahippocampal (AP: −3.0; ML: −1.4; DV: −3.6) | Ipsilateral posterior intracortical (AP: −7.56; ML: −2.5; DV: −1.75)) |

Abbreviations: AP, Anterior – Posterior. ML, Medial – Lateral. DV, Dorsal – Ventral. FPI – Fluid percussion injury. For specific aim 2, bipolar tungsten EEG electrodes coordinates were adjusted using MRI.

Fig. 1.

Electrode placement. Specific Aim 1 and 2 - Location of the craniotomy (orange circle), four subdural recording electrodes (red) C3 (Ipsilateral frontoparietal), C4 Contralateral.

Frontoparietal, O1 Ipsilateral Occipital and O2 Contralateral Occipital and 3 bipolar electrodes (blue) A1,A3 (Ipsilateral anterior intracortical); H1,H3 (Ipsilateral intrahippocampal) and Po1,Po3 (Ipsilateral posterior intracortical). Ground (Gr) electrode (brown) and reference electrode (orange). Grid dimensions 1 mm × 1 mm.

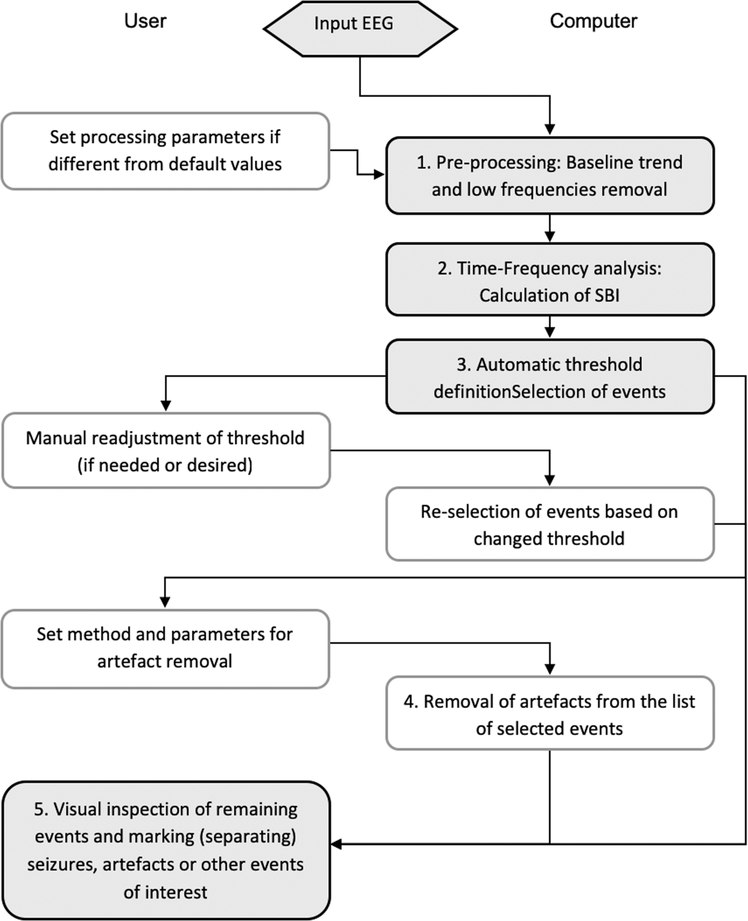

Fig. 2.

Block-diagram of the Assyst algorithm. Shaded boxes: main steps; grey boxes: optional steps. The boxes on the left side indicate operations performed by the user, and boxes on the right side automatically by the Assyst software (Modified from Casillas-Espinosa et al 2019).

2.4. EEG acquisition harmonization

Six months after FPI, animals were connected using cables that allowed them free movement around their cage (Table 3). In the three centers, commutators were used to allow unrestrained movement of the animal, while minimizing torque on the cable and implanted electrode cap.

Table 3.

EEG recording equipment.

| Centre | Amplifier | Bandwidth | Amplification range | References | Input Impedance | Number of channels | Pedestal-commutator | Commutator | Commutator-amplifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UEF | Digital Lynx 16SX (Neuralynx, USA) | 0.01 Hz to 80 kHz | +/− 132 millivolts | 80 independent | 1 GigaOhms | 320 | Flexible shielded cable (M12C-363/2, Plastics One Inc.) | 12-pin swivel SL12C, Plastics One Inc.) | Flexible shielded cable, 363/2–441/12 (PlasticsOne Inc.) |

| Melbourne | Compumedics Neuvo (Compumedics Australia) | 0.01 Hz to 3.5 kHz | +/− 200 mV | 1 common and 64 independent | > 10 GigaOhms | 256 | Flexible shielded cable (M12C-363/2, Plastics One Inc.) | 12-pin swivel SL12C, Plastics One Inc.) | Flexible shielded cable, 363/2–441/12 (PlasticsOne Inc.) |

| UCLA | Intan RHD 2000 (Intan Technologies, USA) | 0.01 Hz – 5 kHz | +/− 200 mV | 4 independent | 1.3 GigaOhms | 128 | Flexible shielded cable (M12C-363/2, Plastics One Inc.) | 12-pin swivel SL12C, Plastics One Inc.) | RHA/RHD2000 18-pin wire adapter for 16-channel amplifier board (Intan Technologies, #B7600) |

In UEF, EEG was acquired using Digital Lynx 16SX amplifier (bandwidth 0.01 Hz – 80 kHz, 80 independent analogical references and 320 channels, Neuralynx, USA), In Melbourne, EEG was acquired using Compumedics Neuvo amplifier (bandwidth 0.01 Hz - 3.5 kHz, 256 channels, 1 common and 64 independent analogical references, Compumedics Australia) and UCLA using the Intan RHD 2000 amplifier (bandwidth 0.01 Hz – 5 kHz, 128 channels, 4 independent analogical references, Intan Technologies, USA). EEG was acquired at a sampling rate of 10 kHz in UEF, 512 Hz-10 kHz in the Melbourne and in UCLA at 2 kHz. In all sites, impedance was maintained below 5–10KΩ and acquisition FIR and high-pass 0.1 Hz filter was used in all sites during acquisition of the EEG. Data was acquired using a resolution of at least 16-bit in the three study sites. Data is collected referentially. The details of the video EEG files are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Video EEG file formats.

| Center | EEG File format | EEG file duration | EEG file size | Sampling rate | Impedance | Acquisition Filter | Video acquisition | Video format | Video duration | Video file size | Synchronization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UEF | .NCS converted to. EDF or. EDF + | 24 h | ∼18 GB per animal | 10 kHz | Initially below 5KΩ. Maintained below 10KΩ | FIR, High-pass 0.1 Hz | High-resolution 1.3 M P, 30 FPS camera (Basler acA1300–75gm GigE, Basler, Germany) | H.264, avi | 24 h | ∼8GB per animal | Synchronized using the precision time protocol IEEE-1588 |

| Melbourne | .EEG converted to. EDF or. EDF + | 24 h | 750 Mb to ∼15 Gb per animal | 512Hz-10kHz | Initially below 5KΩ. Maintained below 10KΩ | FIR, High-pass 0.1 Hz | IP Camera IP816A-HP 2.0 M P @ 30 FPS (Vivotek, Australia). | .avi | 24 h | ∼105GB per session (up to 20 animals) | Automatically synchronized with Profusion5 acquisition software |

| UCLA | .RHD converted to. EDF or. EDF + | 2 h | ∼1.2 GB per animal | 2kHz | Initially below 5KΩ. Maintained below 10KΩ | FIR, High-pass 0.1 Hz | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

FIR, Finite impulse response; Gb, Gigabyte; Hz, Hertz.

3. Justification of the length of continuous EEG monitoring

Our previous experimental data in lateral FPI model indicate that the average seizure frequency is about 0.2/d (Andrade et al., 2018; Kharatishvili et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2016b; Reid et al., 2016).

To calculate the probability of observing one or more seizures on a single animal during the monitoring period, the seizure occurrence was modelled as a Poisson process. A Poisson process is a stochastic process commonly used to model events that are known to occur at random and independently of each other, but at a certain rate that is a constant during the monitoring period. We assume that the lengths of the time intervals between consecutive seizures are independent and exponentially distributed. Given the rate of seizures per day λ and the length of a monitoring period t in days, the probability of an epileptic animal having interval X between seizures longer than the monitoring period is P(X > t) = e−tλ. The probability of observing a seizure on an epileptic animal within the monitoring period is therefore 1 − P(X > t). For example, if λ= 0.2/d and t = 28 d, then the probability of observing a seizure on an epileptic animal within the monitoring period is 99.6%. Assuming an equal seizure rate λ for all animals and independence of intervals between animals, the probability of observing a seizure on each of the n epileptic animals is (1 − P(X > t))n.

Exponentially distributed intervals X are random variables with memoryless property, that is P(X > t + x | X > t) = P(X > x), for x, t ∈ [0, ∞). Therefore, if a seizure has not occurred by time, the remaining time till the next seizure t follows the same distribution as time original time t + x - i.e., the remaining time has no memory of the time already passed. From the memoryless property it follows that the number of seizures within a monitoring period depends only on the length of the period, and not on the location of the period. The monitoring periods can thus be broken into several smaller periods, given the total length of the period is sufficient and that the periods occur after epilepsy has developed.

3.1. EEG analysis

3.1.1. Manual seizure detection

For the manual seizure detection, the EEG recordings were exported into European data format (.edf) and then analyzed using EDF browser software. For review at each study site we used unfiltered signal displayed in 10 and 30 s windows. High pass filter was set at 1 Hz and low pass filter at 70 Hz. An electrographic event was classified as a “seizure” if it showed repetitive epileptiform EEG discharges (rhythmic spike and wave discharges) at > 2 c/s and/or characteristic pattern with quasirhythmic spatio-temporal evolution (i.e. gradual change in frequency, amplitude, morphology and topography), lasting at least several seconds (usually > 10 s) (Brady et al., 2018; Bragin et al., 2016a,b; Gotman, 1982, 1990; Kharatishvili et al., 2006).

3.1.2. Automated seizure analysis

3.1.2.1. Assyst algorithm for automated seizure detection

The Assyst algorithm was used by Melbourne. It is a standalone executable file written in Delphi (Embarcadero Technologies, Austin, TX, USA) that is based on advanced time-frequency analysis which detects the episodes of EEG with excessive activity in the frequency bands of 17–25 Hz that have been found to be specific for seizures (Casillas Espinosa et al., 2019).

EEG recordings were exported into European data format (.edf or. edf+) files and then were loaded into the Assyst software. There are no restrictions on data size, number of channels to be analyzed and EEG recording duration, except the physical memory of the computer. The Assyst algorithm is interactive; some operations are automatically performed by the computer, others required the user input as described in Fig. 2.

3.1.2.2. UEF script for semi-automated seizure detection

UEF performed automated seizure detection by a recently published algorithm (Andrade et al., 2018). This method is based on the calculation of the EEG power spectral density in the recorded channels that are previously averaged. Power in the band 14 and 42 Hz, threshold at 800 uV2 is used to trigger the seizure detector. The positive events are then marked as probable seizures. Finally, an experienced researcher confirmed visually all seizure candidates on a computer screen (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Schematic presentation of the seizure detection algorithm and flow of data analysis. (Sz- seizure) Modified from (Andrade et al., 2018).

4. Results

The proposed pipeline for phenotyping posttraumatic epilepsy after the TBI in a multicenter pre-clinical trial is presented in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Pipeline for phenotyping posttraumatic epilepsy after TBI. TBI, traumatic brain injury; EEG, electroencephalogram.

4.1. Harmonization of timing and implantation of EEG recording electrodes

We used 4 or more EEG recording channels that covered brain areas ipsilateral and contralateral to the site of the injury. Intracerebral electrodes were included in the electrode set-up as they are useful for more accurate seizure identification and were hoped to provide a better insight on the seizure onset zone (Fig. 2A). To appropriately capture seizures, a 6-month timepoint was selected based on our previous studies.

4.2. EEG acquisition

For EpiBios4Rx, we decided that the EEG recording systems had to be able to record a minimum sampling rate of 512 Hz, utilize a Finite impulse response (FIR), high-pass 0.1 Hz filter, and minimum of 4 epidural electrodes (2 for recording one in each hemisphere, one ground and one reference). Impedance was maintained below 10KΩ.

In UEF and Melbourne video was acquired using high-definition camera that provided enough quality to visualize animal behavior. In UEF each cage had its own camera place on the side, outside of the short wall of the cage. In Melbourne, each camera was able to record video from six animals. Cameras were positioned form the side, outside of the short wall of the cages. It was important to ensure that the video monitoring and the EEG are synchronized trough the duration of the recordings. This was achieved using synchronized using the precision time protocol IEEE-1588 in UEF and automatically synchronized using Profusion 5 in Melbourne Video was not acquired in UCLA at this stage.

4.3. Harmonization of EEG quality control criteria

All sites attempted to remove the source of electrical noise if detected, particularly if it was present at the beginning the first EEG recording. Moreover, we confirmed the quality of the ground by ensuring ground cables and connectors were well insulated and avoided ground loops.

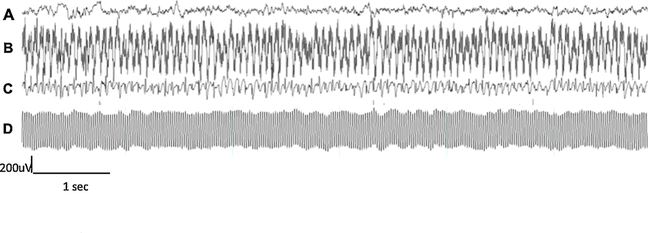

The quality of the EEG recordings was checked daily, as well as the changes of impedance over time and the appearance of new and often external noises. These was achieved by checking the integrity of the cables, stability of the EEG recording cap and the appropriate connection of the electrodes with the cables. Examples of poor-quality EEG recordings are shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Examples of good and bad quality recordings. (A) A good quality EEG recording after applying our quality control criteria. Bad quality EEG recordings due to (B) high- impedance EEG-recording, (C) ground loop recording with a channel recording electrocardiographic activity, and (D) major AC (50 Hz) electrical noise and large impedance recording.

A proportion of chronic EEG recordings contained intermittent artefacts of various extracranial origins as shown in Fig. 6. We made attempts to reduce most of the artefacts, particularly physiological artefacts related to cardiac signal and external artefacts due to other electrical equipment in the room.

Fig. 6.

Examples of different artefacts encountered in our recordings. Physiological artefacts: (A) Electrocardiogram (ECG) and (B) chewing. External artefacts: (C) movement of the EEG cable and (D) large electrical equipment interference.

4.4. Seizure detection

Following the pipeline presented in this article and after applying the quality control criteria to our EEG recordings, the three EpiBioS4Rx sites were able consistently phenotype seizures after TBI. Examples of seizures detected from the three study sites are presented in Figs. 7 and 8.

Fig. 7.

A) Late post-traumatic seizure detected manually. EEG recorded from a rat 6 months after TBI in the left hemisphere. Seizure begins with sharp wave (“onset”) bilaterally that transitions to low amplitude theta rhythm and progressively increases in amplitude and slows in frequency.

Fig. 8.

Representative sample of seizures found six months after TBI.

5. Discussion

5.1. The importance and the challenge to phenotype PTE in large scale cohorts

Prolonged EEG monitoring in chronic epilepsy models has become an important tool in pre-clinical drug development of new therapies (Barker Haliski et al., 2015; Galanopoulou and Mowrey, 2016). Prolonged video-EEG monitoring is the gold standard to phenotype the occurrence of spontaneous seizures in different animal models (Kadam et al., 2017). In anti-seizure, anti-epileptogenesis and disease-modifying trials, prolonged video-EEG is necessary to observe the acute and chronic effects of the drugs on seizures (Galanopoulou and Mowrey, 2016; Kadam et al., 2017). Studies utilizing video-EEG typically involve comparison of measurements obtained from different experimental groups, or from the same experimental group at different times. Given the heterogeneity of epilepsy and, in some cases, the low frequency of spontaneously occurring seizures, it is mandatory to have large number of animals per cohort to appropriately power antiepileptogenesis and disease-modification studies. Moreover, it is necessary to perform multiple and prolonged periods of recording to detect sufficient number of events (e.g. seizures) to gain sufficient statistical power to rigorously establish if the experimental treatments are successful in preventing or modifying the progression of epilepsy (Barker Haliski et al., 2015; Galanopoulou and Mowrey, 2016; Galanopoulou et al., 2013; Kadam et al., 2017). Achieving this will be made more practical by the use of multicenter pre-clinical trials in the context of consortiums, like EpiBioS4Rx, similar to what is standard practice in clinical trials designed to assess the efficacy of disease-modifying therapies.

In preclinical research, EEG recordings usually utilize intracranial electrodes, which are used for monitoring seizures and other epileptiform events. They are also often used to record normal physiological electrical activity to address a specific hypothesis, and therefore electrode placement is consistent within an experiment but may not be consistent across experiments that look for different outcomes or across laboratories.

Here we describe the procedures used in EpiBios4Rx to harmonize EEG acquisition, instrumentation and analysis to phenotype posttraumatic epilepsy. The aim is to provide a pipeline that will help to improve the rigor and reproducibility of pre-clinical research in the search of biomarkers and therapies to prevent antiepileptogenesis. Thus, minimizing the possibility of translational failures.

5.2. Harmonization methods to phenotype PTE - when, where and for how long?

We started the phenotyping of posttraumatic epilepsy 6 months after TBI. In the lateral FPI model, numerous lines of evidence suggest the development of spontaneous recurring seizures occur 4–6 months after TBI (Brady et al., 2018; Kharatishvili et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2016b; Reid et al., 2016).

To record the seizures, we utilized stainless steel screw electrodes implanted into the skull, which are the most commonly used type of electrodes for long-term EEG recordings in rodents. The screw electrodes are placed epidurally trough skull burr holes, only record from the surface of the brain, and therefore, are most useful for monitoring for seizure or other epileptiform activity in cortical brain regions (Hernan et al., 2017; Moyer et al., 2017). The location of the subdural electrodes was standardized across the three study sites. The current placement of the electrodes in the animals enables bilateral and anteroposterior coverage of brain electrical activity, good signal to noise ratio, and stable recordings for several months, all of which are critical for phenotyping posttraumatic epilepsy. However, one of the limitations is the short interelectrode distances due to anatomical spatial constraints and the volume conduction (Hernan et al., 2017). In our experience, a minimum of 2 EEG recording electrodes is necessary to corroborate the seizure activity in the experimental animals (Liu et al., 2016b). Ground and reference electrodes should preferably be implanted in regions outside the primary seizure focus, for example above the cerebellum (Moyer et al., 2017). Here we placed the reference electrode contralateral to the injury site. The location of the reference electrode was selected to be at a distance from the source of activity of interest, in a relatively neutral location that is not contaminated by the activity of the electrode of interest (Hernan et al., 2017).

Intracerebral electrodes are also useful for seizure identification and might provide better localization and characterization of the seizure onset zone (Kadam et al., 2017). The location of intracerebral electrodes for this study were chosen based on previous data on seizure onset zones in the lateral FPI model, that is, perilesional cortex and hippocampal involvement (Bragin et al., 2016a). Moreover, intracerebral microelectrodes are essential to analyses high-frequency brain activity as described by Santana-Gomez et al 2019 in this supplement.

Due to the small amplitude of the biological signals, amplification is necessary. This is usually accomplished using commercial or in-house made amplifiers. These devices will amplify and digitize the signal that is directly acquired through a cable attached from the EEG electrode implants on the head of the rodent (Hernan et al., 2017). The three EpiBioS4Rx canters used different digital systems to record the EEG signals, all of which have been proven useful to record EEG activity in post-TBI animals (Holzer et al., 2006; Kharatishvili et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2016b; Reid et al., 2016). The EEG recordings from all sites underwent similar filtering, amplification, and subsequent display by the same bipolar and referential montages, as described in the methods. Low-pass filtering was used to avoid aliasing of signals above the Nyquist frequency (Moyer et al., 2017). The most critical consideration for analog-to-digital conversion is the Nyquist theorem, which states that a signal at a given frequency must be sampled at least twice per period to be accurately represented. Finite impulse response (FIR) filters were selected because they provide a linear delay and are computational stable (Gliske et al., 2016).

Referential montages are the most commonly used and widely validated in rodents for capturing EEG seizure activity (Hernan et al., 2017; Kadam et al., 2017; Moyer et al., 2017). A referential montage consists of a series of derivations in which the same electrode (the reference electrode) is used for each animal (Moyer et al., 2017). One of the advantages of a common reference in referential montages permits signal localization through amplitude comparisons. Moreover, the data can be re-montaged after collection, permitting more flexible and indepth offline analysis if necessary (Hernan et al., 2017; Moyer et al., 2017).

A 4-week period of continuous video-EEG monitoring was selected to allow us to detect posttraumatic epilepsy after TBI in 99.6% of the cases according to our calculations. The likelihood for correctly diagnosing epilepsy, was calculated assuming that seizure appearance has exponential distribution, and expected frequency based on our previous published experience (Kharatishvili et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2016b; Reid et al., 2016). This long period of monitoring was selected due to the relatively low frequency of spontaneous seizures (0.2 seizures/day) in the lateral FPI, in comparison to other models of acquired epilepsy, like the post-status epilepticus model (Andrade et al., 2018; Bertoglio et al., 2017; Bhandare et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2016b; Van Nieuwenhuyse et al., 2015).

UEF and Melbourne acquired high-definition video synchronized with the EEG, as this is necessary to stratify the behavioral severity of the seizures (Racine, 1972), and can help to phenotype the occurrence of PTE (Kadam et al., 2017). Moreover, video recordings can help to confirm focal seizures without an obvious motor pattern, and enables the exclusion of various types of artifact associated that occur during prolonged EEG monitoring (Kadam et al., 2017; Moyer et al., 2017).

Depending on the number of animals recorded using the same video feed, a minimum video quality of 480p at 30fps is enough to visualize the animal’s gross movements and behavior. The identification of the animal’s movements can sometimes be facilitated by creating enough contrast between the home cage and the animals. Transparent cages and video recorded from the side of cage was preferred as well as bedding that creates some contrast with the animal, for example gray paper litter bedding for white rodents. Another option is to use mirrors, higher video resolution or more video-cameras per animal if trying to phenotype subtle changes in behavior (Kadam et al., 2017).

5.3. Dealing with the most common problems of long-term EEG recordings

One of the major problems in long-term EEG recordings is the presence of electrical noise. Excessive amounts of noise can contaminate and compromise the interpretation of the EEG. Ensuring the quality of the ground is one of the most critical aspects to minimize electrical noise. This is achieved by well insulated ground paths and avoiding ground loops. A ground loop occurs when there are two or more ground points on a circuit that are at different voltage potentials (Annovazzi Lodi and Donati, 1991; Hernan et al., 2017), resulting in a current flow between them that will appear on the recorded signal as unwanted noise, usually 50 or 60 Hz line noise (Moyer et al., 2017). Ground loops occur when multiple animal common connections are in place, but more often occur when multiple earth grounds are in place. To avoid a ground loop, we ensured that animal common connections converge to a single connection at the equipment input. We also unplugged or restricted electrical current to nearby electrical equipment, particularly to large electrical appliances. Another useful strategy to avoid electrical noise is to use electrical isolated rooms, which have been shown to significantly improve the quality of the EEG recordings (Hernan et al., 2017).

Muscle artifacts due to rapid movements like wet dog shakes, sniffing or chewing are relatively common in freely moving animals, however these artifacts are generally removed during post-processing (Moyer et al., 2017). It is important to note, that a good indicator of the quality of the EEG is the ability to identify the different graphoelements belonging to the different sleep stages, like spindles K-complexes, and generalized theta during REM.

Another common problem faced in long-term EEG acquisition recordings is the stability of the caps that are attached to the rat’s skull. Nevertheless, using our previously reported EEG implantation techniques (Kharatishvili et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2016a; Reid et al., 2016), only less than 5% of the animals required re-implantation of the EEG cap.

It was decided that the EEG recording files be managed in epochs of 2–24 h to facilitate the file management and transfer, and also to minimize an extensive data loss in the case of a system failure. The raw data is stored in hard-drives and backed-up using the different cloudbased or enterprise-based storage systems at UEF, Melbourne and UCLA. The archive systems available at each study site provide longterm data storage, protection and redundancy.

To share the data between the different study sites, we selected EDF and EDF + formats, which are the most commonly used format in the field of epilepsy research, with a well-documented file structure and many different available tools to view, annotate import and export these data formats (Kemp and Olivan, 2003). These data files systems facilitate long-term accessibility of the data while also meeting data storage and sharing constraints.

6. Conclusions

One of the key outcomes shown in this work is that, despite differences in equipment used, the three centers were able to consistently phenotype seizures in the lateral FPI model by applying the pipeline presented here. This emphasizes the importance of timing, location of the electrodes and quality control procedures. Importantly, the pipeline presented here can be applicable to other models of seizures and epilepsy, for review see (Brady et al., 2019; Bragin et al., 1999; Casillas Espinosa et al., 2015; Karhunen et al., 2007; Pitkänen et al., 2007; Pitkanen et al., 2005; Van Nieuwenhuyse et al., 2015).

Future work will compare an validate the use of the automated and manuals methods of seizure analysis across all the study sites. Moreover, we will indagate in the validity of intracerebral microelectrodes to help localize the seizure onset in the FPI model of posttraumatic epilepsy and provide and comparison between automated and manual EEG analysis for phenotyping posttraumatic epilepsy.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) Center without Walls of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number U54NS100064 (EpiBioS4Rx).

Footnotes

Disclosures

All authors have nothing to disclose.

This article is part of a special issue ‘Discovery of diagnostic biomarkers for post-traumatic epileptogenesis – an interim analysis of procedures in preclinical multicenter trial EpiBios4Rx’

References

- Andrade P, et al. , 2018. Algorithm for automatic detection of spontaneous seizures in rats with post-traumatic epilepsy. J. Neurosci. Methods 307, 37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annegers JF, Hauser WA, Coan SP, Rocca WA, 1998. A population-based study of seizures after traumatic brain injuries. The New England Journal of Medicine 338, 20–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annovazzi Lodi V, Donati S, 1991. Simultaneous polarographic and electrophysiological in vivo measurements through optoelectronic interconnection. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng 38, 212–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker Haliski M, et al. , 2015. Disease modification in epilepsy: from animal models to clinical applications. Drugs 75, 749–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoglio D, et al. , 2017. Kainic acid-induced post-status epilepticus models of temporal lobe epilepsy with diverging seizure phenotype and neuropathology. Front. Neurol 8, 588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandare A, et al. , 2017. Inhibition of microglial activation with minocycline at the intrathecal level attenuates sympathoexcitatory and proarrhythmogenic changes in rats with chronic temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroscience 350, 23–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady R, et al. , 2019. Modelling traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic epilepsy in rodents. Neurobiol. Dis 123, 8–19. 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.08.007. Epub 2018 Aug 16. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragin A, Li L, Almajano J, Alvarado Rojas C, Reid A, Staba R, Engel J, 2016a. Pathologic electrographic changes after experimental traumatic brain injury. Epilepsia 57, 735–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragin A, et al. , 1999. High-frequency oscillations in human brain. Hippocampus 9, 137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragin A, et al. , 2016b. Pathologic electrographic changes after experimental traumatic brain injury. Epilepsia 57, 735–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casillas Espinosa P, et al. , 2015. Z944, a novel selective T-Type calcium channel antagonist delays the progression of seizures in the amygdala kindling model. PLoS One 10, e0130012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casillas Espinosa P, et al. , 2019. A universal automated tool for reliable detection of seizures in rodent models of acquired and genetic epilepsy. Epilepsia 123, 8–19. 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.08.007. Epub 2018 Aug 16. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen J, Pedersen M, Pedersen C, Sidenius P, Olsen J, Vestergaard M, 2009b. Long-term risk of epilepsy after traumatic brain injury in children and young adults: a population-based cohort study. Lancet (British edition) 373, 1105–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englander J, Bushnik T, Duong T, Cifu D, Zafonte R, Wright J, Hughes R, Bergman W, 2003b. Analyzing risk factors for late posttraumatic seizures: a prospective, multicenter investigation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil 84, 365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey, 2003. L.Frey. E pidemiology of posttraumatic epilepsy: a critical review. Epilepsia 44 Suppl 10,2003 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou A, Mowrey W, 2016. Not all that glitters is gold: a guide to critical appraisal of animal drug trials in epilepsy. Epilepsia Open 1, 86–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou A, et al. , 2012. Identification of new epilepsy treatments: issues in preclinical methodology. Epilepsia 53, 571–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanopoulou AS, et al. , 2013. Joint AES/ILAE translational workshop to optimize preclinical epilepsy research. Epilepsia 54 (Suppl. 4), 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gliske S, et al. , 2016. Effect of sampling rate and filter settings on High Frequency Oscillation detections. Clin. Neurophysiol 127, 3042–3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotman J, 1982. Automatic recognition of epileptic seizures in the EEG. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol 54, 530–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotman J, 1990. Automatic seizure detection: improvements and evaluation. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol 76, 317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman S, 2002. Epilepsy after brain insult: targeting epileptogenesis. Neurology 59, S21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernan A, et al. , 2017. Methodological standards and functional correlates of depth in vivo electrophysiological recordings in control rodents. A TASK1-WG3 report of the AES/ILAE Translational Task Force of the ILAE. Epilepsia 58 (Suppl. 4), 28–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer M, et al. , 2006. 4D functional imaging in the freely moving rat. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc 1, 29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immonen R, et al. , 2009. Distinct MRI pattern in lesional and perilesional area after traumatic brain injury in rat–11 months follow-up. Exp. Neurol 215, 29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadam S, et al. , 2017. Methodological standards and interpretation of video-electroencephalography in adult control rodents. A TASK1-WG1 report of the AES/ILAE Translational Task Force of the ILAE. Epilepsia 58 (Suppl. 4), 10–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karhunen H, et al. , 2007. Epileptogenesis after cortical photothrombotic brain lesion in rats. Neuroscience 148, 314–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp B, Olivan J, 2003. European data format’ plus’ (EDF+), an EDF alike standard format for the exchange of physiological data. Clin. Neurophysiol 114, 1755–1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharatishvili I, et al. , 2006. A model of posttraumatic epilepsy induced by lateral fluid-percussion brain injury in rats. Neuroscience 140, 685–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis S, et al. , 2012. A call for transparent reporting to optimize the predictive value of preclinical research. Nature 490, 187–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapinlampi N, et al. , 2017. Common data elements and data management: remedy to cure underpowered preclinical studies. Epilepsy Res. 129, 87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S-J, et al. , 2016a. Sodium selenate retards epileptogenesis in acquired epilepsy models reversing changes in protein phosphatase 2A and hyperphosphorylated tau. Brain 139, 1919–1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SJ, et al. , 2016b. Sodium selenate retards epileptogenesis in acquired epilepsy models reversing changes in protein phosphatase 2A and hyperphosphorylated tau. Brain 139, 1919–1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein D, 2009. Epilepsy after head injury: an overview. Epilepsia 50 (Suppl. 2), 4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer J, et al. , 2017. Standards for data acquisition and software-based analysis of in vivo electroencephalography recordings from animals. A TASK1-WG5 report of the AES/ILAE Translational Task Force of the ILAE. Epilepsia 58 (Suppl. 4), 53–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C, 1986. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, 2nd ed. Academic Press, Sydney. [Google Scholar]

- Pitkänen A, Engel J, 2014. Past and present definitions of epileptogenesis and its biomarkers. Neurotherapeutics 11, 231–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkänen A, McIntosh T, 2006. Animal models of post-traumatic epilepsy. J. Neurotrauma 23, 241–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkanen A, et al. , 2005. Administration of diazepam during status epilepticus reduces development and severity of epilepsy in rat. Epilepsy Res. 63, 27–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkänen A, et al. , 2007. Epileptogenesis in experimental models. Epilepsia 48 (Suppl. 2), 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine RJ, 1972. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol 32, 281–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid A, et al. , 2016. The progression of electrophysiologic abnormalities during epileptogenesis after experimental traumatic brain injury. Epilepsia 57, 1558–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shultz S, et al. , 2015. Sodium selenate reduces hyperphosphorylated tau and improves outcomes after traumatic brain injury. Brain 138, 1297–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonato M, et al. , 2014. The challenge and promise of anti-epileptic therapy development in animal models. Lancet Neurol. 13, 949–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Nieuwenhuyse B, et al. , 2015. The systemic kainic acid rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy: Long-term EEG monitoring. Brain Res. 1627, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]