Abstract

Premise

Chloroplast primers were developed for phylogenetic and comparative studies in Thalictrum (Ranunculaceae).

Methods and Results

We assembled and annotated the complete plastome sequence of T. thalictroides by combining multiple whole genome sequencing libraries. Using transcriptome‐sequencing libraries, we also assembled a partial plastome of the related species T. hernandezii. From the newly assembled plastomes and one previously sequenced plastome, we designed and validated 28 primer pairs to target variable portions of the chloroplast genome in Thalictrum. Furthermore, we tested the validated primers in 62 species of Thalictrum. The total alignment length of the 28 regions was 15,268 bp with 2443 variable sites and 92% character occupancy.

Conclusions

The newly developed chloroplast primer pairs improve the phylogenetic resolution (bootstrap support and tree certainty) in Thalictum and will be a useful resource for future phylogenetic and evolutionary studies for species in the genus and in close relatives in Thalictroideae.

Keywords: chloroplast genome, high‐throughput sequencing, meadow‐rue, microfluidic PCR, Ranunculaceae, Thalictrum thalictroides

The chloroplast genome (cpDNA) has been particularly useful for resolving evolutionary relationships in plants for the past 30 years (reviewed in Gitzendanner et al., 2018). High‐throughput sequencing has facilitated the development of various approaches for collecting multiple regions or complete sequences of this genome (reviewed in Twyford and Ness, 2016). Furthermore, approaches based on PCR target enrichment in combination with high‐throughput sequencing (e.g., Uribe‐Convers et al., 2016) have proven to be a cost‐effective approach for sequencing multiple chloroplast regions simultaneously, and have been successfully applied in phylogenetic studies (e.g., Jacobs et al., 2018; Morales‐Briones and Tank, 2019).

Thalictrum L. (Thalictroideae, Ranunculaceae) is a clade of ca. 190 species of herbaceous perennials distributed primarily in northern temperate regions (Tamura, 1995) with a diversity of sexual systems (hermaphroditic, dioecious, andromonoecious, or gynomonoecious [Boivin, 1944]), pollination mode (insect or wind [Soza et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2018]), and ploidy (from 2x =14 to 30x = 210 [Soza et al., 2013]). To date, molecular phylogenetic studies of Thalictrum have relied on sequences of the nuclear ribosomal DNA (nrDNA) cistron, especially the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and external transcribed spacer (ETS) regions, and up to five cpDNA regions (Soza et al., 2012, 2013; Wang et al., 2018). Although Soza et al. (2013) surveyed several cpDNA regions from Shaw et al. (2007), only one was identified as sufficiently variable for phylogenetic analyses in Thalictrum. Here, we assembled and annotated the complete plastome of T. thalictroides (L.) A. J. Eames & B. Boivin, assembled a partial plastome of T. hernandezii Tausch ex J. Presl, and designed and validated PCR primers that target highly variable chloroplast regions in Thalictrum to aid in future phylogenetic studies of this group and close relatives.

METHODS AND RESULTS

Plastome assembly

Genomic libraries of T. thalictroides and transcriptome libraries of T. hernandezii were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive (Appendix 1). Due to low cpDNA coverage in the transcriptome libraries, a reference‐guided assembly of T. hernandezii was carried out using Alignreads version 2.5.2 (Straub et al., 2011) with T. coreanum H. Lév. as a reference (Park et al., 2015), with one inverted repeat (IR) removed. We obtained a plastid consensus sequence made of 151 contigs representing 116,700 bp (after removal of regions not covered in the reference) for T. hernandezii. Given the availability of multiple genome sequencing libraries for two samples of T. thalictroides (Appendix 1), we performed de novo assemblies for this species. Assemblies were carried out for the two individuals of T. thalictroides (WT478 and WTBG) separately using the Fast‐Plast version 1.2.6 pipeline (McKain and Wilson, 2017). Single contigs representing the complete chloroplast genome of T. thalictroides were obtained. The resulting complete plastomes of T. thalictroides were annotated using CpGAVAS (Liu et al., 2012). Genes encoding for tRNAs were verified using tRNAscan‐SE version 2.0 (Lowe and Chan, 2016). Annotations were verified and edited in Geneious version 7.1.9 (Kearse et al., 2012) using other available Ranunculaceae plastomes as references (Appendix 1). The genome map was drawn with OGDraw version 1.2 (Lohse et al., 2013). Characterization of the T. thalictroides plastome and its comparison with the plastome of T. coreanum (Park et al., 2015) can be found in Appendix S1.

Primer design

Plastome sequences of T. thalictroides, T. hernandezii, and T. coreanum (all with one IR removed) were aligned using MAFFT version 7.017b (Katoh and Standley, 2013). The most variable regions of the alignment, spanning 400–600 bp, were identified using a custom R script (Uribe‐Convers et al., 2016). Primer design was carried out using Primer3 (Untergasser et al., 2012) following the specifications of the microfluidic PCR Access Array system protocol (Fluidigm, San Francisco, California, USA), with an annealing temperature of 60°C (±1°C) and no more than three continuous nucleotides of the same base. Primer validation followed Uribe‐Convers et al. (2016) by simulating the four‐primer reaction of the microfluidic PCR. We used our target‐specific primers and 5′ conserved sequence (CS) tags to provide annealing sites for Illumina sequencing adapters and sample‐specific barcodes. PCR validations were done using genomic DNA from three Thalictrum species (Appendix 2) and a negative control that did not contain DNA. Amplicons were visualized in a QIAxcel Advanced System (QIAGEN, Valencia, California, USA) and scored following Uribe‐Convers et al. (2016).

A total of 81 primer pairs were designed, of which 28 passed the validation step (Table 1), 32 failed (i.e., failed to amplify in one or more species, produced significant primer dimers, and/or produced multiple amplicons), and 21 were not validated (Appendix S2). In order to test cross‐amplification of the 28 validated PCR primer pairs, we amplified and sequenced these regions on 75 individuals of Thalictrum representing 62 species from 13 of 14 described sections of the genus (Tamura, 1995). Our sampling represents 33% of Thalictrum species and 70% of the sampling used in the most recent molecular phylogeny of the genus (Wang et al., 2018). Additionally, we amplified the newly designed regions from one individual each of three related genera in Thalictroideae (Aquilegia L., Leptopyrum Rchb., and Paraquilegia J. R. Drumm. & Hutch.; Appendix 2) using previously extracted DNA samples by Soza et al. (2012). Microfluidic PCR was carried out on the Access Array system (Fluidigm) following the manufacturer's protocol. PCR amplicons were multiplexed, and sequenced in an Illumina MiSeq (San Diego, California, USA) with 300‐bp paired‐end reads. Raw reads were cleaned, demultiplexed, and merged using the dbcAmplicons pipeline (Uribe‐Convers et al., 2016). Consensus sequences for each sample in all amplicons were generated using the ‘reduce_amplicons’ R script (part of dbcAmplicons). Each chloroplast region was aligned with MAFFT and alignment summary statistics were calculated with AMAS (Borowiec, 2016).

Table 1.

Sequence of validated primers for the Thalictrum chloroplast genome.a

| Locus | Primer sequences (5′–3′)b | Amplification region | Chloroplast region | Amplicon length, bpc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| thal‐13 | F: GCAATAAGTCCGGTTTGCAT | atpA, (atpA‐atpF) IGS, atpF | LSC | 550 |

| R: GGGCGATGAAAGAAATAAACG | ||||

| thal‐15 | F: ACATGGCTTTCTTCCATAACG | (atpH‐aptI) IGS, atpI | LSC | 574 |

| R: GAATCCATGGAGGGTCATCA | ||||

| thal‐44 | F: TGAAGTGATAGCCCGATTCC | (rbcL‐accD) IGS, accD | LSC | 518 |

| R: TTTCCAGTTCATTCCGATCA | ||||

| thal‐45 | F: TGATGGGTCTAAGAGTGACAATCA | accD | LSC | 419 |

| R: CGATTCTTTCTGAACTGCTCATT | ||||

| thal‐46 | F: TTTGCAGCATTGAGTAAGGAAC | (ycf4‐cemA) IGS | LSC | 577 |

| R: CCCGAACGAGTCATTTCAA | ||||

| thal‐47 | F: GAGAAGGTTCAATTGTCCGAAA | petA, (petA‐psbJ) IGS, psbJ | LSC | 572 |

| R: GGTATTCTTGTGATCGGTTTACTAGG | ||||

| thal‐50 | F: TGAGGTGATTGGATTTGCAC | (rpl20‐clpP) IGS, clpP | LSC | 558 |

| R: CGAAGACATGGAAAGGGATG | ||||

| thal‐51 | F: AACCCTTGTGAGGGTTTCG | clpP | LSC | 541 |

| R: GAGGCCTCTTTCCAATATTTATGTTA | ||||

| thal‐52 | F: TTACATATTGCGAAGGCATAGTCT | clpP | LSC | 414 |

| R: TGAACCGTATGCATCCAAAG | ||||

| thal‐53 | F: AAGAATCAATGTGCTGATTCCA | clpP | LSC | 534 |

| R: GTATCCAGGCTCCGTTCAGA | ||||

| thal‐54 | F: TCTGAACGGAGCCTGGATAC | clpP, (clpP‐psbB) IGS | LSC | 560 |

| R: TTCGTAGGAACAAAGATAAGCAGA | ||||

| thal‐55 | F: TGCTCTTGTATCTTTCGCCTCT | (psbB‐psbT) IGS, psbT, (psbT‐psbN) IGS, psbN, (psbN‐psbH) IGS | LSC | 525 |

| R: CATTGCGGTCTTGCAATTT | ||||

| thal‐57 | F: CTGGCTCCGTAAGATCCAGT | petD | LSC | 513 |

| R: CGAAGGAACCGGACATGATA | ||||

| thal‐58 | F: GGAGCAACATTGCCTATTGATAA | petD, (petD‐rpoA) IGS, rpoA | LSC | 546 |

| R: CAATCAAGGCAGGGTTACTTTAC | ||||

| thal‐59 | F: TAACCCTGCCTTGATTGTCC | rpoA | LSC | 565 |

| R: GGAACATGTATCACACGAGCA | ||||

| thal‐61 | F: TCGAATTGTTATTCAACCCTATAGAA | (rpl16‐rps3) IGS, rps3 | LSC | 597 |

| R: AATCGATCTGATCCAGGTCATAA | ||||

| thal‐62 | F: CCCTCGGTCTATTAGTGAACCA | ycf2 | IR | 562 |

| R: CCAAGCTCGAAGTACCATTTG | ||||

| thal‐64 | F: ATATGCGCCCTCCACCTAC | ndhF | SSC | 379 |

| R: TTTGATTGGTATGAATTTGTGAGAA | ||||

| thal‐65 | F: ATGGATCCGACGAACAAAGT | ndhF | SSC | 541 |

| R: GGCTCTTATGGGCGGTTTA | ||||

| thal‐68 | F: TGTGTGGATCATTATTATCAGTAGCTC | ccsA | SSC | 506 |

| R: TGAACCATAACTATGCAGCCCTA | ||||

| thal‐69 | F: AAAGGTCTTACAAATCCAATACGC | (ccsA‐ndhD) IGS, ndhD | SSC | 581 |

| R: CTCGATGGCTTCTCTTGCAT | ||||

| thal‐70 | F: CCCAGAACTCCCATTAAGAGAA | ndhD | SSC | 483 |

| R: TTTCCCTCATAGAGGAAATAAGGTT | ||||

| thal‐72 | F: CCGATGGATAATAAATAGGCACTC | ndhE, (ndhE‐ndhG) IGS, ndhG | SSC | 591 |

| R: TGTGATGTTCATCAATGGTTCA | ||||

| thal‐74 | F: TCCGCTTAGCTTAACCCTTG | ndhA | SSC | 525 |

| R: TCGTTTATTCAGTATCGGACCA | ||||

| thal‐75 | F: AACACTCCGATCTCCTATCAGAA | ndhH | SSC | 530 |

| R: GGATAGATAAATGTTTGGATTTCTGTG | ||||

| thal‐78 | F: TGCGGCACTAATCTAGACCATC | ycf1 | SSC | 542 |

| R: TCCCGACTAATACGTAAATGTCAC | ||||

| thal‐80 | F: TCTGAATACCGTCGATTAACCA | ycf1 | SSC | 503 |

| R: ATGCGTGCTCAAAGACGTAA | ||||

| thal‐81 | F: CGTATCAAAGCCACTTCGTCT | ycf1 | SSC | 578 |

| R: CATCGCGGAACAATCAAA |

IR = inverted repeat region; LSC = large single copy region; SSC = small single copy region.

Primer pairs were designed for an annealing temperature of 60°C (±1°C). Validation consisted of successful (single amplicon) amplification on three test species and absence of (or minimal) primer dimer detection.

Conserved sequence tags CS1 (5′‐ACACTGACGACATGGTTCTACA) and CS2 (5′‐TACGGTAGCAGAGACTTGGTCT) were added to each primer to make target‐specific primer for microfluidic PCR.

Estimated from three Thalictrum species, including primer length.

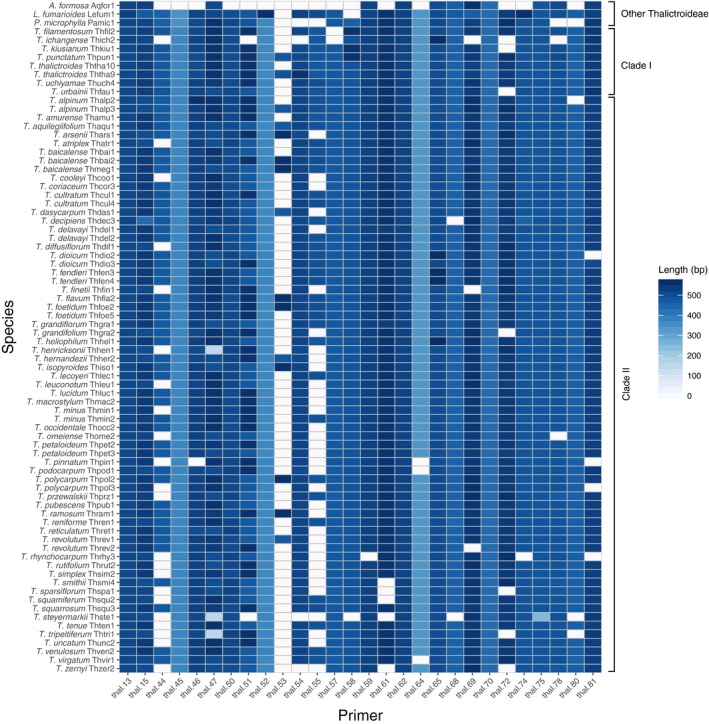

The cross‐amplification and sequencing resulted in regions with 15–75 (mean 69) consensus sequences of Thalictrum. Two regions, thal‐53 and thal‐55, had lower amplification success, with 15 and 40 sequences, respectively (Table 2, Fig. 1, Appendix S3). The amplification success per sample ranged from 19 to 28 (mean 26) regions. The amplification success in Aquilegia, Leptopyrum, and Paraquilegia was 12, 26, and 23 regions, respectively (Fig. 1), showing the potential utility of the newly developed primers on related genera in Thalictroideae. Thalictrum‐only alignment lengths ranged from 335 to 658 bp (mean 525 bp; Appendix S3), with the number of variable sites ranging from nine to 195 (mean 73). Alignments including the other Thalictroideae genera ranged from 335 to 725 bp (mean 544; Appendix S3) in length and contained 29–218 (mean 86) variable sites (Table 2). The total alignment length of the 28 regions (including all genera) was 15,268 bp, with 2443 variable sites and 92% character occupancy.

Table 2.

Alignment summary statistics for 28 amplified chloroplast regions in Thalictrum and relatives.

| Locus | Thalictrum | Thalictrum + Aquilegia + Leptopyrum + Paraquilegia | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment length, bp | No. of sequences | Sequence length range, bp (mean) | Pairwise identity, % | Variable sites, bp (PI) | Alignment length, bp | No. of sequences | Sequence length range, bp (mean) | Pairwise identity, % | Variable sites, bp (PI) | |

| thal‐13 | 515 | 75 | 509–515 (509) | 99.50 | 28 (12) | 531 | 78 | 509–522 (509) | 99.40 | 42 (14) |

| thal‐15 | 605 | 75 | 434–544 (525) | 93.70 | 85 (36) | 632 | 78 | 434–544 (524) | 93.00 | 128 (45) |

| thal‐44 | 496 | 53 | 466–479 (473) | 98.50 | 33 (20) | 500 | 55 | 457–479 (472) | 98.10 | 45 (22) |

| thal‐45 | 372 | 75 | 372–372 (372) | 99.00 | 24 (15) | 372 | 77 | 345–372 (371) | 98.50 | 30 (15) |

| thal‐46 | 615 | 74 | 500–561 (521) | 96.10 | 142 (34) | 630 | 76 | 500–561 (520) | 95.80 | 152 (43) |

| thal‐47 | 658 | 75 | 150–554 (518) | 83.50 | 195 (140) | 725 | 78 | 150–554 (518) | 83.40 | 218 (150) |

| thal‐50 | 545 | 75 | 499–517 (506) | 97.50 | 30 (14) | 556 | 77 | 495–517 (506) | 97.20 | 43 (14) |

| thal‐51 | 594 | 73 | 461–557 (512) | 85.20 | 190 (140) | 599 | 75 | 461–557 (511) | 85.20 | 197 (142) |

| thal‐52 | 381 | 75 | 366–377 (370) | 99.60 | 16 (11) | 571 | 77 | 366–558 (372) | 98.10 | 45 (11) |

| thal‐53 | 585 | 15 | 469–560 (520) | 85.60 | 126 (78) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| thal‐54 | 567 | 72 | 505–558 (514) | 98.30 | 76 (17) | 575 | 73 | 505–558 (514) | 98.20 | 78 (18) |

| thal‐55 | 504 | 40 | 474–495 (486) | 97.30 | 28 (19) | 524 | 41 | 474–501 (486) | 97.10 | 32 (19) |

| thal‐57 | 495 | 73 | 464–480 (473) | 99.00 | 36 (23) | 496 | 75 | 464–480 (473) | 98.90 | 45 (25) |

| thal‐58 | 568 | 74 | 482–556 (485) | 98.10 | 39 (19) | 573 | 75 | 458–556 (485) | 97.90 | 48 (21) |

| thal‐59 | 524 | 74 | 518–524 (524) | 99.40 | 33 (18) | 524 | 77 | 518–524 (524) | 99.20 | 53 (18) |

| thal‐61 | 590 | 70 | 532–553 (552) | 96.10 | 153 (107) | 591 | 72 | 532–553 (552) | 96.00 | 165 (110) |

| thal‐62 | 519 | 75 | 519–519 (519) | 99.80 | 9 (7) | 525 | 78 | 519–525 (519) | 99.70 | 29 (7) |

| thal‐64 | 335 | 72 | 335–335 (335) | 98.50 | 50 (30) | 335 | 74 | 335–335 (335) | 98.40 | 58 (36) |

| thal‐65 | 579 | 75 | 496–563 (504) | 96.80 | 77 (34) | 586 | 78 | 496–563 (504) | 96.70 | 93 (39) |

| thal‐68 | 456 | 73 | 447–456 (456) | 98.90 | 47 (29) | 474 | 76 | 447–468 (456) | 98.60 | 71 (38) |

| thal‐69 | 616 | 72 | 521–558 (545) | 96.00 | 96 (64) | 620 | 75 | 462–558 (544) | 95.30 | 111 (62) |

| thal‐70 | 436 | 75 | 436–436 (436) | 99.20 | 38 (20) | 436 | 78 | 436–436 (436) | 99.00 | 52 (24) |

| thal‐72 | 658 | 68 | 530–556 (542) | 97.10 | 66 (30) | 662 | 70 | 530–556 (542) | 96.70 | 103 (42) |

| thal‐74 | 495 | 74 | 454–488 (482) | 98.40 | 38 (21) | 593 | 76 | 454–560 (483) | 97.60 | 50 (21) |

| thal‐75 | 488 | 75 | 249–480 (477) | 97.70 | 104 (15) | 486 | 78 | 249–480 (477) | 97.80 | 82 (23) |

| thal‐78 | 508 | 73 | 469–502 (484) | 98.10 | 54 (33) | 556 | 75 | 469–502 (485) | 97.50 | 83 (35) |

| thal‐80 | 460 | 72 | 454–460 (460) | 98.10 | 105 (40) | 460 | 73 | 454–460 (460) | 97.90 | 118 (44) |

| thal‐81 | 545 | 71 | 502–545 (529) | 97.40 | 121 (62) | 551 | 74 | 502–545 (529) | 97.00 | 146 (67) |

PI = parsimony informative; NA= not applicable.

Figure 1.

Cross‐amplification performance of chloroplast primers for phylogenetic studies in Thalictrum. Amplification results in 62 species of Thalictrum and one species of Aquilegia, Leptopyrum, and Paraquilegia (outgroups) with the 28 validated primer pairs. Darker shades of blue represent longer amplification products; white represents failed amplification. Thalictrum clades sensu Soza et al. (2012, 2013).

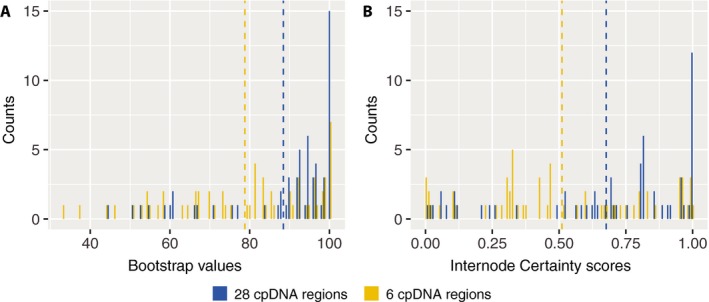

To test the usefulness of the newly generated chloroplast primers for improving phylogenetic resolution within Thalictrum, we inferred a phylogeny of 62 Thalictrum species (one individual per species) and three outgroups using all 28 regions and compared it to an inferred phylogeny of the same species using six chloroplast regions (ndhA, rbcL, rpl16, rpl32‐trnL, trnL‐trnF, and trnV‐ndhC) (Soza et al., 2012, 2013; Wang et al., 2018). For each concatenated matrix, we searched for the best partition scheme followed by maximum likelihood tree inference and 1000 ultrafast bootstrap replicates for node support using IQ‐Tree version 1.6.10 (Nguyen et al., 2014). As an additional measure of tree resolution, we estimated internode certainty scores (Salichos et al., 2014) using the majority rule consensus tree across 1000 bootstrap replicates in RaxML version 8.2.11 (Stamatakis, 2014). The six‐region matrix had an aligned length of 6650 bp and 363 parsimony‐informative sites, whereas the 28‐region matrix had an aligned length of 15,268 bp and 1045 parsimony‐informative sites. Mean bootstrap values of the 28‐region trees were higher than those of the six‐region trees (89% and 79%, respectively; Fig. 2A). Moreover, mean internode certainty scores were also higher in the 28‐region tree (0.68 and 0.51, respectively; Fig. 2B). In summary, these results show that the 28‐region chloroplast matrix produces a tree with overall higher node support than the six‐region matrix, and is therefore suitable for improved phylogenetic studies in Thalictrum and close relatives.

Figure 2.

Overall performance of chloroplast primers for phylogenetic studies in Thalictrum. (A) Bootstrap value distribution of the 28‐region (blue) and six‐region (yellow) phylogenies. Dashed lines represent mean values. (B) Internode certainty scores distribution of the 28‐region (blue) and six‐region (yellow) phylogenies. Dashed lines represent median scores.

CONCLUSIONS

Here, we contribute chloroplast primers for phylogenetic and comparative studies of Thalictrum and its close relatives in Thalictroideae. Furthermore, we demonstrate the utility of whole genome and transcriptome libraries as a source of chloroplast sequence data for PCR primer design. Out of the 81 chloroplast primer pairs reported here, 28 were successfully validated for use with the high‐throughput, Fluidigm‐based microfluidic PCR system. Finally, although this was not directly tested here, these primers could also be used for traditional PCR.

Supporting information

APPENDIX S1. Characterization of the Thalictrum thalictroides plastome and comparison to the plastome of T. coreanum.

APPENDIX S2. Primer sequences of the Thalictrum chloroplast genome that failed to pass our validation criteria or were not validated.

APPENDIX S3. Length (in base pairs) of 28 amplified chloroplast regions in Thalictrum and relatives.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded through the National Science Foundation Science and Technology Center on evolution in action (BEACON; NSF DBI‐0939454 with an internal award to D.C.T. and V.S.D.). Whole genome and transcriptome sequencing were funded by the Research and Conference Grants Administration System (RCGAS) of The University of Hong Kong's Small Project Funding to T.A. Publication of this article was funded in part by the University of Idaho Open Access Publishing Fund and The Fred C. Gloeckner Foundation, Inc. Access to computational resources was granted through the University of Idaho Institute for Bioinformatics and Evolutionary Studies (IBEST) supported by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (P30 GM103324).

APPENDIX 1. Source of genomic resources used for plastome assembly and annotation.

| Species | Sample code | Usage | Accession no. | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thalictrum hernandezii Tausch ex J. Presl | WT441 | Partial plastome assembly and primer design | SRA: SRR6869419, SRR6869420 | Transcriptome libraries. Libraries represent staminate and hermaphrodite flowers from one andromonoecious individual. |

| T. thalictroides (L.) A. J. Eames & B. Boivin | WT478 | Whole plastome assembly and primer design | SRA: SRR6869426, SRR6869425, SRR6869418 | Genomic libraries. Each library has different insert size. |

| T. thalictroides | WTBR | Whole plastome assembly | SRA: SRR6869424, SRR6869423, SRR6869421 | Genomic libraries. Each library has different insert size. |

| T. coreanum H. Lév. | — | Primer design and plastome annotation | GenBank: NC026103 | |

| Aconitum chiisanense Nakai | — | Plastome annotation | GenBank: NC029829 | |

| Megaleranthis saniculifolia Ohwi | — | Plastome annotation | GenBank: NC012615 | |

| Ranunculus macranthus Scheele | — | Plastome annotation | GenBank: DQ359689 |

APPENDIX 2. Voucher information for species of Thalictrum used for primer validation and cross‐amplification.

| Species | Sample code | Voucher (Herbarium) | Locality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aquilegia formosa Fisch. ex DC. | Aqfor1 | V. Di Stilio 128 (WTU) | Di Stilio Garden, Seattle, WA, USA |

| Leptopyrum fumarioides (L.) Rchb. | Lefum1 | A. Liston 819‐13 (RSA) | Xinjiang, China |

| Paraquilegia microphylla (Royle) J. R. Drumm. & Hutch. | Pamic1 | I. Smirnov 277 (RSA) | Irkutsk, Arshan, Russia |

| Thalictrum alpinum L. | Thalp2 | D. E. Boufford et al. 32249 (F) | Xizang (Tibet), China |

| Thalictrum alpinum L. | Thalp3 | V. Di Stilio 115 (WTU) | Cultivated from Ion Exchange Nursery, Iowa, USA |

| Thalictrum amurense Maxim. | Thamu1 | Unvouchered | Cultivated at UC Botanical Garden at Berkeley, CA, USA |

| Thalictrum aquilegiifolium L. | Thaqu1 | V. Di Stilio 108 (WTU) | Cultivated material from Cricklewood Nursery, CA, USA |

| Thalictrum arsenii B. Boivin | Thars1 | A. Liston 1128 (OSC) | Mpio. Morelia, Jaripeo, Michoacan, Mexico |

| Thalictrum atriplex Finet & Gagnep. | Thatr1 | D. E. Boufford et al. 32557 (GH) | Xizang (Tibet), China |

| Thalictrum baicalense Turcz. | Thbai1 | Unvouchered | Cultivated at University of Washington Botany Greenhouse, Seattle, USA, from seeds from B & T World Seeds |

| Thalictrum baicalense Turcz. | Thbai2 | R. Zhang 20120614‐01 (PE) | Ecological station, Dong Lin Mtn., China |

| Thalictrum baicalense Turcz. | Thmeg1 | D. E. Boufford et al. 37958 (GH) | Sichuan, Danba Xian, China |

| Thalictrum cooleyi H. E. Ahles | Thcoo1 | Unvouchered | The State Botanical Garden of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA |

| Thalictrum coriaceum (Britton) Small | Thcor3 | A. Floden s.n. (TENN) | Greene Co., TN, USA |

| Thalictrum cultratum Wall. | Thcul1 | D. E. Boufford et al. 31166 (F) | Xizang (Tibet), China |

| Thalictrum cultratum Wall. | Thcul4 | D. E. Boufford et al. 31233 (GH) | Xizang (Tibet), China |

| Thalictrum dasycarpum Fisch. & Avé‐Lall. | Thdas1 | V. Di Stilio 110 (WTU) | Cultivated from Ion Exchange Nursery, Iowa, USA |

| Thalictrum decipiens B. Boivin | Thdec3 | L. Galetto 2089 (CORD) | Pampa de Achala, Córdoba, Argentina |

| Thalictrum delavayi Franch. | Thdel1 | D. E. Boufford et al. 30452 (F) | Sichuan, Xiangcheng Xian, China |

| Thalictrum delavayi Franch. | Thdel2 | V. Di Stilio 121 (WTU) | Cultivated from seed from B & T World Seeds, Aigues‐Vives, France |

| Thalictrum diffusiflorum C. Marquand & Airy Shaw | Thdif1 | A. Liston 1161 (OSC) | Cultivated from Heronswood Nursery, Kingston, WA, USA |

| Thalictrum dioicum L. | Thdio3 | M. Sain 60 (WIS) | University of Wisconsin campus, Muir Woods, Madison, WI, USA |

| Thalictrum dioicum L. | Thdio2 | V. Di Stilio 101 (A) | Lithia Springs, South Hadley, MA, USA |

| Thalictrum fendleri Engelm. ex A. Gray | Thfen4 | Unvouchered | Cultivated at UW Botany Greenhouse, Seattle, USA |

| Thalictrum fendleri Engelm. ex A. Gray | Thfen3 | V. Soza 1920 (WTU) | Cultivated from Heronswood Nursery, Kingston, WA, USA |

| Thalictrum filamentosum Maxim. | Thfil2 | V. Di Stilio 104 (WTU) | Cultivated from Heronswood Nursery, Kingston, WA, USA |

| Thalictrum finetii B. Boivin | Thfin1 | D. E. Boufford et al. 33172 (GH) | Sichuan, Jiulong Xian, China |

| Thalictrum flavum L. | Thfla2 | V. Di Stilio 109 (WTU) | Cultivated from Heronswood Nursery, Kingston, WA, USA |

| Thalictrum foetidum L. | Thfoe5 | Unvouchered | Cultivated from Arrowhead Alpines nursery, Michigan, USA |

| Thalictrum foetidum L. | Thfoe2a | V. Soza 1923 (WTU) | Cultivated from Arrowhead Alpines nursery, Michigan, USA |

| Thalictrum grandiflorum Maxim. | Thgra1 | Unvouchered | Cultivated from Heronswood Nursery, Kingston, WA, USA |

| Thalictrum grandifolium S. Watson | Thgra2 | G. B. Hinton 20254 (TEX) | Coahuila, Mexico |

| Thalictrum heliophilum Wilken & DeMott | Thhel1 | Mary Waters s.n. (CS) | Cathedral Bluffs, Rio Blanco County, CO, USA |

| Thalictrum henricksonii M. C. Johnst. | Thhen1 | J. Henrickson 13417 (RSA) | Zacatecas, Mexico |

| Thalictrum hernandezii Tausch ex J. Presl | Thher2a | A. Liston 1125 (OSC) | Temascaltepec, State of Mexico, Mexico |

| Thalictrum ichangense Lecoy. ex Oliv. | Thich2 | A. Floden 13116 (TENN) | Sapa, Lao Cai Province, Vietnam |

| Thalictrum isopyroides C. A. Mey. | Thiso1 | V. Di Stilio 111 (WTU) | Cultivated from Heronswood Nursery, Kingston, WA, USA |

| Thalictrum kiusianum Nakai | Thkiu1 | J. Brunet s.n. (OSC) | Cultivated at Corvallis, OR, USA |

| Thalictrum lecoyeri Franch. | Thlec1 | D. E. Boufford et al. 37972 (GH) | Sichuan, Danba Xian, China |

| Thalictrum leuconotum Franch. | Thleu1 | D. E. Boufford et al. 42102 (GH) | Yunnan, Zhongdian Xian, China |

| Thalictrum lucidum L. | Thluc1 | V. Di Stilio 122 (WTU) | Cultivated from Arrowhead Alpines nursery, Michigan, USA |

| Thalictrum macrostylum Shuttlew. ex Small & A. Heller | Thmac2 | Unvouchered | “Serpentine Barrens,” Chunky Gal Mountain, NC, USA |

| Thalictrum minus L. | Thmin1 | H. W. Rickett & F. A. Stafleu 742 (OSC) | Gelderland, Netherlands |

| Thalictrum minus L. | Thmin2 | V. Soza 1910 (WTU) | Cultivated at University of Washington Botany Greenhouse, Seattle, WA, USA |

| Thalictrum occidentale A. Gray | Thocc2 | K. A. Beck 200712 (WTU) | Lower Boundary Dam Reservoir, Pend Oreille River, WA, USA |

| Thalictrum omeiense W. T. Wang & S. H. Wang | Thome2 | A. Liston 1166 (OSC) | Cultivated from Heronswood Nursery, Kingston, WA, USA |

| Thalictrum petaloideum L. | Thpet3 | Unvouchered | Dong Ling Mt., Betula Forest, Beijing, China |

| Thalictrum petaloideum L. | Thpet2 | Unvouchered | Tong Ling Mt., Yin Ranje, Beijing, China |

| Thalictrum pinnatum S. Watson | Thpin1 | R. M. Straw & M. Forman 1857 (RSA) | Chihuahua, Mexico |

| Thalictrum podocarpum Kunth ex DC. | Thpod1 | M. Weigend 2000/623 (OSC) | Ancash, Huaylas, Pampanomas, Peru |

| Thalictrum polycarpum (Torr.) S. Watson | Thpol3 | B. Keller s.n. (UC) | Cultivated at University of California Botanical Garden at Berkeley, CA, USA |

| Thalictrum polycarpum (Torr.) S. Watson | Thpol2 | J. F. Smith 4572 (WTU) | Cassia County, Idaho, USA |

| Thalictrum przewalskii Maxim. | Thprz1 | D. E. Boufford et al. 36521 (GH) | Sichuan, Dege Xian, China |

| Thalictrum pubescens Pursh | Thpub1 | D. Baum & D. Howarth 375 (A) | Arnold Arboretum, Jamaica Plain, MA, USA |

| Thalictrum punctatum H. Lév. | Thpun1 | V. Di Stilio 117 (WTU) | Cultivated from Heronswood Nursery, Kingston, WA, USA |

| Thalictrum ramosum B. Boivin | Thram1 | A. Larsen s.n. (UC) | Cultivated at UC Botanical Garden at Berkeley, CA, USA |

| Thalictrum reniforme Wall. | Thren1 | B. Keller s.n. (UC) | Cultivated at University of California Botanical Garden at Berkeley, CA, USA |

| Thalictrum reticulatum Franch. | Thret1 | D. E. Boufford et al. 42802 (GH) | Sichuan, Muli Xian, China |

| Thalictrum revolutum DC. | Threv2 | A. Floden 1347 (TENN) | Campbell County, TN, USA |

| Thalictrum revolutum DC. | Threv1 | V. Soza 1917 (WTU) | Cultivated from USDA AMES #28275 |

| Thalictrum rhynchocarpum Quart.‐Dill. & A. Rich. | Thrhy3 | W. Kindeketa 820 (MO) | Arusha, Tanzania |

| Thalictrum rutifolium Hook. f. & Thomson | Thrut2 | D. E. Boufford et al. 32127 (GH) | Xizang (Tibet), Riwoqe Xian, China |

| Thalictrum simplex L. | Thsim2 | V. Soza 1914 (WTU) | Cultivated from USDA GRIN AMES #23805 |

| Thalictrum smithii B. Boivin | Thsmi4 | D. E. Boufford et al. 28205 (A) | Sichuan, Daocheng Xian, Gongling, China |

| Thalictrum sparsiflorum Turcz. ex Fisch. & C. A. Mey. | Thspa1 | M. Williams 1630 (OSC) | 7 miles from Seward, AK, USA |

| Thalictrum squamiferum Lecoy. | Thsqu2 | D. E. Boufford et al. 32003 (GH) | Xizang (Tibet), Riwoqe Xian, China |

| Thalictrum squarrosum Stephan ex Willd. | Thsqu3 | X. Duan 20120617 (PE) | Cultivated at CAS Botanical Garden, Beijing, China |

| Thalictrum steyermarkii Standl. | Thste1 | T. B. Croat 40494 (MO) | Chiapas, Mexico |

| Thalictrum tenue Franch. | Thten1 | W. Zhai 20120615 (PE) | Wanging, Henan, China |

| Thalictrum thalictroides (L.) A. J. Eames & B. Boivin | Ththa10a | V. Di Stilio 124 (WTU) | Cultivated from Arrowhead Alpines nursery, Michigan, USA |

| Thalictrum thalictroides (L.) A. J. Eames & B. Boivin | Ththa9 | V. Di Stilio 123 (WTU) | Cultivated from natural population from Massachusetts, USA |

| Thalictrum tripeltiferum B. Boivin | Thtri1 | L. E. Detling 8788 (ORE) | Jalisco, Mexico |

| Thalictrum uchiyamae Nakai | Thuch4 | V. Di Stilio 113 (WTU) | Cultivated from seed from B & T World Seeds, Aigues‐Vives, France |

| Thalictrum uncatum Maxim. | Thunc2 | D. E. Boufford et al. 30691 (GH) | Sichuan, Xiangcheng Xian, China |

| Thalictrum urbainii Hayata = T. fauriei Hayata | Thfau1 | A. Liston 1162 (OSC) | Cultivated from Heronswood Nursery, Kingston, WA, USA |

| Thalictrum venulosum Trel. | Thven2 | Voucher lost at OSC | NA |

| Thalictrum virgatum Hook. f. & Thomson | Thvir1 | D. E. Boufford et al. 30496 (GH) | Sichuan, Xiangcheng Xian, China |

| Thalictrum zernyi Ulbr. | Thzer2 | R. E. Gereau & C. J. Kayombo 3976 (MO) | Iringa, Ludewa, Tanzania |

NA = not available; s.n. = unnumbered.

Sample used for primer validation and cross‐amplification.

Morales‐Briones, D. F. , Arias T., Di Stilio V. S., and Tank D. C.. 2019. Chloroplast primers for clade‐wide phylogenetic studies of Thalictrum . Applications in Plant Sciences 7(10): e11294.

Contributor Information

Verónica S. Di Stilio, Email: distilio@u.washington.edu.

David C. Tank, Email: dtank@uidaho.edu.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The complete plastome of T. thalictroides and partial plastome of T. hernandezii were deposited in GenBank (MH092833 [WTBR], MH092834 [WT478], and MK716276). The alignment used for primer design (with primer and gene annotations), raw sequence data from the 28 amplified regions for the 78 samples of Thalictrum and relatives, alignments, and phylogenetic trees are available from the Dryad Digital Repository (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.hv4k73n; Morales‐Briones et al., 2019).

LITERATURE CITED

- Boivin, B. 1944. American Thalictra and their old world allies. Contributions from the Gray Herbarium of Harvard University 152: 337–491. [Google Scholar]

- Borowiec, M. L. 2016. AMAS: A fast tool for alignment manipulation and computing of summary statistics. PeerJ 4: e1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitzendanner, M. A. , Soltis P. S., Yi T.‐S., Li D.‐Z., and Soltis D. E.. 2018. Plastome phylogenetics: 30 years of inferences into plant evolution In Chaw S.‐M. and Jansen R. [eds.], Advances in Botanical Research, volume 85: Plastid genome evolution, 293–313. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, S. J. , Kristofferson C., Uribe‐Convers S., Latvis M., and Tank D. C.. 2018. Incongruence in molecular species delimitation schemes: What to do when adding more data is difficult. Molecular Ecology 27: 2397–2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh, K. , and Standley D. M.. 2013. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 772–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearse, M. , Moir R., Wilson A., Stones‐Havas S., Cheung M., Sturrock S., Buxton S., et al. 2012. Geneious Basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28: 1647–1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. , Shi L., Zhu Y., Chen H., Zhang J., Lin X., and Guan X.. 2012. CpGAVAS, an integrated web server for the annotation, visualization, analysis, and GenBank submission of completely sequenced chloroplast genome sequences. BMC Genomics 13: 715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse, M. , Drechsel O., Kahlau S., and Bock R.. 2013. OrganellarGenomeDRAW—a suite of tools for generating physical maps of plastid and mitochondrial genomes and visualizing expression data sets. Nucleic Acids Research 41: W575–W581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, T. M. , and Chan P. P.. 2016. tRNAscan‐SE On‐line: Integrating search and context for analysis of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Research 44: W54–W57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKain, M. , and Wilson M.. 2017. mrmckain/Fast‐Plast: Fast‐Plast v.1.2.6 (Version v.1.2.6). Zenodo. 10.5281/zenodo.973887 [accessed 1 July 2017]. [DOI]

- Morales‐Briones, D. F. , and Tank D. C.. 2019. Extensive allopolyploidy in the neotropical genus Lachemilla (Rosaceae) revealed by PCR‐based target enrichment of the nuclear ribosomal DNA cistron and plastid phylogenomics. American Journal of Botany 106: 415–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales‐Briones, D. F. , Arias T., Di Stilio V. S., and Tank D. C.. 2019. Data from: Chloroplast primers for clade‐wide phylogenetic studies of Thalictrum . Dryad Digital Repository. 10.5061/dryad.hv4k73n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, L.‐T. , Schmidt H. A., von Haeseler A., and Minh B. Q.. 2014. IQ‐TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum‐likelihood phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution 32: 268–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, S. , Jansen R. K., and Park S.. 2015. Complete plastome sequence of Thalictrum coreanum (Ranunculaceae) and transfer of the rpl32 gene to the nucleus in the ancestor of the subfamily Thalictroideae. BMC Plant Biology 15: 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salichos, L. , Stamatakis A., and Rokas A.. 2014. Novel information theory–based measures for quantifying incongruence among phylogenetic trees. Molecular Biology and Evolution 31: 1261–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, J. , Lickey E. B., Schilling E. E., and Small R. L.. 2007. Comparison of whole chloroplast genome sequences to choose noncoding regions for phylogenetic studies in angiosperms: The tortoise and the hare III. American Journal of Botany 94: 275–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soza, V. L. , Brunet J., Liston A., Smith P. S., and Di Stilio V. S.. 2012. Phylogenetic insights into the correlates of dioecy in meadow‐rues (Thalictrum, Ranunculaceae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 63: 180–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soza, V. L. , Haworth K. L., and Di Stilio V. S.. 2013. Timing and consequences of recurrent polyploidy in meadow‐rues (Thalictrum, Ranunculaceae). Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 1940–1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis, A. 2014. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post‐analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30: 1312–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub, S. C. , Fishbein M., Livshultz T., Foster Z., Parks M., Weitemier K., Cronn R. C., and Liston A.. 2011. Building a model: Developing genomic resources for common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) with low coverage genome sequencing. BMC Genomics 12: 211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, M. 1995. Ranunculaceae In Hiepko P. [ed.], Die Natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien, 223–497. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Twyford, A. D. , and Ness R. W.. 2016. Strategies for complete plastid genome sequencing. Molecular Ecology Resources 17: 858–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Untergasser, A. , Cutcutache I., Koressaar T., Ye J., Faircloth B. C., Remm M., and Rozen S. G.. 2012. Primer3—new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Research 40: e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uribe‐Convers, S. , Settles M. L., and Tank D. C.. 2016. A phylogenomic approach based on PCR target enrichment and high throughput sequencing: Resolving the diversity within the South American species of Bartsia L. (Orobanchaceae). PLoS ONE 11: e0148203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T. N. , Clifford M. R., Martínez‐Gómez J., Johnson J. C., Riffell J. A., and Di Stilio V. S.. 2018. Scent matters: Differential contribution of scent to insect response in flowers with insect vs. wind pollination traits. Annals of Botany 123: 289–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

APPENDIX S1. Characterization of the Thalictrum thalictroides plastome and comparison to the plastome of T. coreanum.

APPENDIX S2. Primer sequences of the Thalictrum chloroplast genome that failed to pass our validation criteria or were not validated.

APPENDIX S3. Length (in base pairs) of 28 amplified chloroplast regions in Thalictrum and relatives.

Data Availability Statement

The complete plastome of T. thalictroides and partial plastome of T. hernandezii were deposited in GenBank (MH092833 [WTBR], MH092834 [WT478], and MK716276). The alignment used for primer design (with primer and gene annotations), raw sequence data from the 28 amplified regions for the 78 samples of Thalictrum and relatives, alignments, and phylogenetic trees are available from the Dryad Digital Repository (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.hv4k73n; Morales‐Briones et al., 2019).