Abstract

Contrast agents (CAs) play a crucial role in high-quality magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) applications. At present, as a result of the Gd-based CAs which are associated with renal fibrosis as well as the inherent dark imaging characteristics of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles, Mn-based CAs which have a good biocompatibility and bright images are considered ideal for MRI. In addition, manganese oxide nanoparticles (MONs, such as MnO, MnO2, Mn3O4, and MnOx) have attracted attention as T1-weighted magnetic resonance CAs due to the short circulation time of Mn(II) ion chelate and the size-controlled circulation time of colloidal nanoparticles. In this review, recent advances in the use of MONs as MRI contrast agents for tumor detection and diagnosis are reported, as are the advances in in vivo toxicity, distribution and tumor microenvironment-responsive enhanced tumor chemotherapy and radiotherapy as well as photothermal and photodynamic therapies.

Keywords: manganese oxide nanoparticles, MRI, multimodal imaging, contrast agent, tumor therapy

Introduction

Molecular imaging technology is of great value for tumor detection and prognosis monitoring as a result of its high accuracy and reliability for elucidating biological processes and monitoring disease conditions.1,2 Various imaging techniques which are currently in widespread use include optical imaging (OI), X-ray computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography/single photon emission computed tomography (PET/SPECT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasound (US) imaging, while multimodal imaging technologies including photoacoustic (PA) tomography are being developed.3–5

Among these techniques, MRI has become one of the most powerful means of clinical detection and prognosis observation as a result of its non-invasive, high spatial resolution, non-ionizing radiation, and soft tissue contrast.6 While MRI is the best imaging technique for detecting soft tissue, the long relaxation time of water protons leads to weak differences between tissues, resulting in poor image depiction between typical and malignant tissue.7 Fortunately, magnetic resonance contrast agent (CA) has the ability to enhance contrast, thereby improving the sensitivity of magnetic resonance diagnosis. Approximately 35% of the clinical magnetic resonance scans require the use of CAs.8 Therefore, in order to obtain high-quality molecular imaging for clinical diagnosis, many researchers have explored the CAs of MRI.9

In order to improve imaging contrast sensitivity, various T1- or T2-MRI CAs based on gadolinium (Gd), manganese (Mn), and iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4 NPs) have been developed.10 Gd-based T1 CAs in the form of ionic complexes have been extensively used in clinical practice.11 However, usual small size complex-based agents tend to suffer from short blood circulation time and distinct toxicity in vivo, which has the potential to cause nephrogenic systemic fibrosis and cerebral deposition.12–14 Researchers have turned to superparamagnetic nanoparticles, especially Fe3O4 NPs. In the past 20 years, a few T2 CAs based on Fe3O4 NPs have entered clinical trials or been approved by US Food and Drug Administration.15 Unfortunately, these nanoparticles have been somewhat limited in their clinical application due to their intrinsic dark signals and susceptibility artifacts in MRI, which means it is difficult to make a distinction between small early stage tumors and hypointense areas.16,17 Therefore, Mn-based CAs are considered ideal substitutes due to their bright signals and good biocompatibility.

Mn-based CAs can be divided into two major categories: Mn2+ composites and manganese oxide nanoparticles (MONs). Unfortunately, Mn2+ complexes have short blood circulation times18 while high doses of Mn2+ can accumulate in the brain, causing manganese poisoning to manifest as changes in central nervous system activity, resulting in cognitive, psychiatric, and movement abnormalities.19–21 As a result, Mn2+ chelate is not an ideal candidate for an MR CA. However, MONs emerging in recent years have exhibited negligible toxicity22 and good T1-weighted contrast effects.23 Surprisingly, these MONs can respond to tumor microenvironments (TME), such as pH, H2O2 or glutathione (GSH), in order to enhance MRI, alleviate tumor hypoxia and enhance therapy treatment.24 Therefore, MONs have been extensively studied in the field of magnetic resonance CAs.

In recent years, the relaxivity and toxicological properties of MONs25 as well as the chemistry and magnetic resonance performance of responsive Mn-based CAs have been reviewed.26 However, according to the current literature, few reviews have been conducted specifically on the progress of MONs in both tumor imaging and enhanced therapeutic effect in the past six years. Therefore, in this review, we divided MONs into four categories: MnO, Mn3O4, MnO2, and MnOx and reviewed their achievements as MR CAs in MRI, bimodal and multimodal imaging as well as imaging-guided tumor therapy, respectively. This review also covers surface modification, toxicity in vitro and in vivo, and the tumor microenvironment-responsive performance of MONs-based materials.

MnO-Based Nanoparticles In Tumor Diagnosis And Therapy

Mn(II) ion is a key factor which is necessary for MnOs to have strong MRI ability, as the five unpaired electrons in its 3d orbital can produce a large magnetic moment and cause nearby water proton relaxation.25 This means that MnO NPs are potential candidates for T1-weighted MR CAs. Surface coating is a common method for improving the relaxation rate of MnO NPs, such as polymer functionalization,27,28 silica coating,29 phospholipid modification,30 and so on. Additionally, researchers have recently integrated MnO NPs with other modal CAs or nanotheranostic agents to provide more comprehensive information for clinical research. Table 1 highlights some examples based on MnO nanoparticles as imaging CAs and nanotheranostic agents in vivo.

Table 1.

Representative Examples Of MnO-Based Nanoparticles As Contrast Agents And Nanotheranostic Agents In Vivo

| Single Mode Imaging Contrast Agents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Materials | Targets | Imaging Modality | Animal Model | Reference |

| mPEG&cRGD-g-PAsp@MnO | cRGD | T1-MRI | A549 tumor-bearing mice | 28 |

| PEG-MnO | AS1411 | T1-MRI | 786-0 tumor-bearing mice | 27 |

| MnO-TETT-FA | folic acid | T1-MRI | Tiny brain glioma bearing mice | 34 |

| MnO modified with PEG | RGD | T1-MRI | M21 tumor-bearing mice | 33 |

| MnO@PVP | \ | T1-MRI | Healthy KM mice | 35 |

| mPEG-SA-DA@MnO | \ | T1-MRI | A 4-week male ICR mouse | 32 |

| MnO@PDns | \ | T1-MRI | Healthy balb/c female mice | 31 |

| Multimodal imaging contrast agents | ||||

| Materials | Targets | Imaging Modality | Animal Model | Reference |

| Fe3O4@MnO/mSiO2-CD133 | CD133 | T1- and T2-MRI | Adult Sprague−Dawley rats | 37 |

| Fe3O4/MnO–Cy5.5–CTX | CTX | NIRF/T1- and T2-MRI | Glioma-bearing mice | 44 |

| MnO-PEG-Cy5.5 | \ | NIRF/T1-MRI | Glioma-bearing nude mice | 40 |

| MnO-TETT | \ | Fluorescence/T1-MRI | Glioma-bearing mice | 42 |

| MnO@Au | \ | T1-MR/PA/CT Imaging | HepG2-bearing mice | 45 |

| Au@HMSN/Au&MnO-PEI | \ | US/MR/CT Imaging | VX2 tumor–bearing rabbits | 2 |

| Nanotheranostic agents | ||||

| Materials | Treatment agents | Imaging-guided treatment | Animal model | Reference |

| MnO@CNSs | CNSs | MRI-guided PTT | 4T1 tumor-bearing BABL/c mice | 14 |

| MWNTs-MnO-PEG | MWNTs | MR and dark dye imaging-guided PTT | Mice exhibiting LNs metastases | 53 |

| IR808@MnO | IR808 | NIR fluorescence/PA/MR imaging-guided PTT | MCF-7 cell tumor-bearing nude mice | 54 |

| MnO and DTX co-loaded PTNPs | DTX | MR and fluorescence imaging-guided chemotherapy | Human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 tumor-bearing mice | 52 |

| USMO@MSNs-Dox | Dox | MRI-guided chemotherapy | HeLa cells-bearing BABL/c nude mice | 51 |

Abbreviations: mPEG, methoxypolyethylene glycols; cRGD, cyclic arginine-glycine-aspartic acid; PAsp, poly(aspartic acid); mPEG&cRGD-g-PAsp, mPEG and cRGD-grafted PAsp; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PEG, poly (ethylene glycol); TETT, N-(trimethoxysilylpropyl) ethylene diamine triacetic acid; FA, folic acid; RGD, arginine-glycine-aspartic acid; PVP, poly(vinylpyrrolidone); mPEG-SA-DA, dopamine-terminated mPEG linked with succinic anhydride; PDns, pegylated bis-phosphonate dendrons; mSiO2, mesoporous silica; CTX, chlorotoxin; NIRF, near-infrared fluorescence; PA, photoacoustic; CT, X-ray computed tomography; HMSN, hollow mesoporous silica nanoparticle; PEI, polyethylenimine; US, ultrasound; CNSs, carbonaceous nanospheres; PTT, photothermal therapy; MWNTs, multi-walled carbon nanotubes; DTX, docetaxel; PTNPs, polymeric theranostic nanoparticles; USMO@MSNs, ultrasmall manganese oxide-capped mesoporous silica nanoparticles; Dox, doxorubicin.

MnO As Contrast Agents In Magnetic Resonance Imaging

With the advantages of small volume, easy preparation, and low toxicity, MnO nanoparticles are good T1 CAs. However, MnO nanoparticles may be retained by the reticuloendothelial system and subsequently enriched in the liver and spleen, leading to Mn2+-induced toxic effects. In order to reduce the toxicity of MnO in vivo, Chevallier and colleagues attached pegylated bis-phosphonate dendrons (PDns) to the surface of MnO, which greatly improved colloidal stability, relaxation performance (r1=4.4 mM−1s−1, r2=37.8 mM−1s−1, 1.41 T) and rapid excretion ability. In addition, the MnO nanoparticles with a hydrodynamic diameter of 13.4±1.6 nm were eventually discharged through the hepatobiliary pathway as feces, urinary excretion, and so on.31

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) coating has the potential to significantly improve the biocompatibility and physiological stability of nanoparticles and can also be conjugated with specific polypeptides and other aptamers in order to greatly improve the targeting capacities of nanoparticles. Therefore, PEG-modified MnO has been favored by many researchers. As an example, PEG-MnO NPs with a hydrodynamic diameter of 15.08±2.67 nm synthesized by Li and colleagues had a T1 relaxation rate of 12.942 mM−1s−1 and a low r2/r1 ratio of 4.66 at 3.0 T, three times that of clinically used Gd-based CAs.27 In addition, the AS1411 aptamer introduced by covalent cross-linking not only confers the PEG-MnO nanoprobe’s ability to target 786–0 renal cancer tumor cells but can also prolong the storage time of the probe in tumor cells. Huang and colleagues coated MnO nanoparticles with dopamine-functionalized PEG (mPEG-SA-DA).32 They verified that this approach can achieve the best hydrophilicity and higher longitudinal relaxation rate (16.14 mM−1s−1) when coating density reaches 6.51 mmol m−2. In order to enhance probe targeting, mPEG&cRGD-g-PAsp@MnO nanoparticles (r1=10.2 mM−1s−1, r2=62.3 mM−1s−1, 3 T) were obtained by conjugating MnO nanoparticles and poly(aspartic acid)-based graft polymer (containing PEG and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid groups) before being conjugated with cRGD.28 And the hydrodynamic diameter of the conjugated nanoparticles was about 100 nm with a polydispersity index of 0.24. The nanoprobe was high targeting and was capable of accumulating in tumors and prolonging blood circulation time. Similarly, Gallo et al functionalized MnO nanoparticles with PEGylated RGD peptides in order to target the tumor overexpressing αvβ3 integrin.33 The r1 and r2 values were calculated to be 1.44 mM−1s−1 and 3.98 mM−1s−1 at 9.4 T, respectively. They also investigated the effect of PEG chain length on MR imaging. These authors found that long-chain PEG molecules (5000 DaI) have the potential to lead to a higher accumulation of high integrin tumors over a long period of time (24 hours) than short-chain PEG (600 DaI).

In addition, magnetic nanomaterials have been demonstrated to couple with mesoporous silicon, noble metals, carbon-based materials, and fluorophores to function more efficiently. Li et al coated MnO nanoparticles with carboxymethyl dextran (CMDex-MONPs) (r1=0.44 mM−1s−1, r2=3.45 mM−1s−1, 3.0 T).17 Chen and colleagues improved the water solubility of MnO through the use of transesterified oleic acid with N-(trimethoxysilylpropyl) ethylenediamine triacetic acid (TETT) silane.34 Hu et al coated polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) on MnO NPs using layer-by-layer electrostatic assembly. In particular, MnO@PVP NPs can pass through the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and gradually metabolize to other sites with blood flow. This is indicated as an intravascular MRI CA (r1=1.937 mM−1s−1, r2=27.879 mM−1s−1, 3.0 T) and a potential application in basic neuroscience research.35 Hsu et al encapsulated MONPs with silica-F127 (PEO106PPO70PEO106) in order to make them highly hydrophilic. In addition, under the same conditions, the porous silica-PEO nanocoating layer has the ability to enhance the contrast of T1 (r1=1.17 mM−1s−1, r2=30.73 mM−1s−1, 7.0 T) when compared to PEG-phospholipids, dense silica, and mesoporous silica.29 In addition, the structure of MnO can affect its relaxation properties. Octagonal MnO nanoparticles have a larger surface area than spherical nanoparticles of the same size, resulting in significant enhancement of low-temperature ferromagnetic behavior. Therefore, the r1 value of the 85 nm polyethylene glycol dopamine (PEG600-DPA) coated octahedral MnO nanoparticles at a concentration of 0.194 mM is similar to that of the 17 nm spherical nanoparticles at a concentration of 0.254 mM.36

MnO As MR Contrast Agents In Bimodal And Multimodal Imaging

Malignant tumors pose a serious threat to human health. Improving accurate diagnosis of tumors remains a challenging problem. In order to simultaneously obtain a tumor’s overall and local image information, as well as to realize the integration of preoperative and intraoperative diagnosis and treatment, multimodal imaging has become a research hotspot and an area for future development due to its ability to integrate various imaging modes.

T1-weighted images can be used to highlight anatomical structures, while T2-weighted images are more suitable for pathological recognition. T1-T2 dual-mode imaging combination is able to significantly improve MRI efficiency. The contrast effect of the T1-T2 dual-mode contrast agent is distance-dependent. To avoid signal quenching, the distance between T1 NPs and T2 NPs is greater than 20 nm. Nowadays, different methods for combining MnO (T1 CA) and Fe3O4 (T2 CA) in order to construct T1-T2 dual-mode contrast agents (DMCAs) have been extensively studied. For example, Peng and colleagues synthesized Fe3O4@MnO/mSiO2 NPs by loading MnO into the core-shell pores of Fe3O4@mSiO2.37 They found that when the MnO cluster was bound to the nano-effect zone of Fe3O4, local induction of DMCAs can be adjusted by altering the size of Fe3O4 to reduce the damage of MRI to host cells. In order to verify this conclusion, they coupled an anti-CD133 antibody to the surface of Fe3O4@MnO/mSiO2 for live brain cell imaging. Results showed a higher T1-T2 contrast imaging effect and no local damage under strong MRI magnetic field. Mn-doped Fe3O4 and MnO magnetic nanoparticles were then co-loaded onto an oxidized graphene (GO) sheet as T1 and T2 MR CA.38 The distance between MnO NPs and Fe3O4 NPs was greater than 20 nm for avoiding signal quenching.

Due to the reliability and utility of both MRI and optical imaging dual-mode in tumor diagnosis and treatment, optical/magnetic resonance dual-mode probes which are based on MnO nanoparticles have flourished. Zheng et al obtained an MR/near-infrared imaging bimodal nanoprobe (MnO-Cy5.5) by conjugating a near-infrared (NIR) dye Cy5.5 to the MnO surface. The probe was effective in infarcted myocardium accumulates. The co-localization of near-infrared fluorescence (NIRF) imaging with leukocytes and macrophages in the infarcted area means that it is a potential tool for accurate quantitative infarct areas.39 Similarly, Chen and colleagues synthesized the MnO-PEG-Cy5.5 probe, which can enhance the T1 contrast of large-volume glioma imaging.40 Hsu et al encapsulated both coumarin-545T (C545T) and MnO nanoparticles mixed loading into silica nanoshells in order to obtain a pH-responsive fluorescence and MRI dual-mode probe (MCNCs). Under neutral conditions, MnO nanoparticles have a fluorescence quenching effect for C545T, while in an acidic environment, the dissolution of MnO nanoparticles into Mn2+ leads to a 7-fold increase in T1 contrast and fluorescence recovery. In addition, the further coupling of the dual-mode probe with folic acid (FA) conferred the ability of MCNCs to target tumor cells and delayed fluorescence recovery, resulting in an enhanced target background signal ratio and higher sensitivity after activation.41

Some methods which do not use fluorescent dye have been introduced. Lai et al found that MnO which has been obtained through the thermal decomposition of an excess of oleic acid (oleic acid: manganese content > 2) displays fluorescence excitation characteristics across its entire visible spectrum.42 To verify its bio-imaging performance, C6 cells were detected following surface modification of TETT, and it was found that cells exhibited blue and green fluorescence at 405 nm and 458 nm, respectively. Additionally, the longitudinal relaxation rate (r1) at 7T was 4.68 mM−1s−1. Interestingly, Banerjee et al accidentally discovered the formation of a fluorophore when heat-treating pyrrolidin-2-one modifying MnO.43 Cell experiments initially suggested that these MnO nanoparticles support bioluminescence imaging, although the exact luminescent substances remain unclear.

Multi-modal probes enable simultaneous multi-source image processing, which results in more accurate information. In order to minimize the imaging impact of each of the components, the structure and components of the entire probe must be carefully designed. Li and colleagues synthesized Fe3O4/MnO-Cy5.5-CTX NPs for NIRF and T1-/T2-MR multimodal imaging in vitro and in vivo. The CTX (chlorotoxin) is a glioma ligand.44 Zhang et al designed a highly efficient US/MR/CT multimodal probe (Au@HMSN/Au&MnO).2 Large-sized Au nanoparticles were positioned in the cavity of the hollow mesoporous silica nanoparticles (HMSNs), while small-sized Au and MnO are evenly distributed in the mesoporous shell. The grayscale increment from HMSN to Au@HMSN/Au&MnO (46.9) was much larger than the sum of HMSN to HMSN/MnO (9.9) and Au@HMSN/Au (22.5), achieving 1+1≥2 of ultrasonic performance. Specifically, the polyethyleneimine (PEI)-modified Au@HMSN/Au&MnO-PEI1800 demonstrated no obvious cytotoxicity in vitro and in vivo within 30 days. In vivo evaluation experiments found that the probe accumulated in large numbers (6.39%) in rabbit liver VX2 tumors. In addition, the contrast of US imaging was significantly enhanced, while the MR signal intensity of VX2 tumors increased from 63 to 87 and the HU value of CT increased from 75 to 130, which was much larger than that of a typical liver. Liu et al reported a tumor microenvironment (TME)-responsive MR/PA/CT trimodal tumor imaging CA, namely MnO nanocrystals wrapped in porous gold nanoclusters (MnO@Au NCs).45 PA imaging has non-invasive, high-resolution, and accurate quantification in the detection of tumor pathophysiological statuses such as microvessel density, blood oxygen saturation, and hemodynamics.46 However, the PA imaging visualization area is small. CT imaging has the characteristics of whole-body imaging and tissue-free penetration depth limitation, but it cannot distinguish the subtle differences between soft tissues.47 Magnetic resonance imaging is the best choice for soft tissue detection. Therefore, combined MR/PA/CT multi-mode imaging on a nano-platform enables more accurate tumor diagnosis. This porous layer can retard the release of Mn2+ to enhance T1 contrast and increase PA imaging depth. Following the injection of MnO@Au NCs into HepG2 tumor-bearing mice, the PA signal was significantly enhanced and subcutaneous micro-vessels in the depth range of 3.5–9.3 mm were clearly observed. An intratumoral injection of MnO@Au NCs in vivo CT imaging studies was performed. The HU value at the tumor site increased from 115.3 to 657.1. Results showed that this strategy has a satisfactory enhancement effect on MR/PA/CT tumor imaging.

MnO As MR Contrast Agents In Imaging-Guided Tumor Therapy

Nanomedicine has the ability to greatly increase the dose and accuracy of targeted drug delivery to reduce toxic side effects, meaning it can treat tumors more effectively under non-invasive conditions. The loading of therapeutic drugs or combination of some clinical therapies to achieve simultaneous diagnosis and treatment of tumors has been extensively studied. MnO has some unique advantages for treating tumors. Water-dispersible manganese oxide nanocrystals which have been obtained by microwave-assisted methods can induce true autophagy and are independent of P53 activation.48 This autophagy enhancement helps manganese oxide nanocrystals to synergize with chemotherapeutic drugs in order to produce greater lethality against tumors. The triphenylphosphonium (PPh3) is able to explore mitochondrial membrane potential. MnO@SiO2-PPh3+ NPs with mitochondrial targeting were efficiently taken up by HeLa cells.49 This probe is highly specific for mitochondria. It induces severe cytotoxicity within four hours and causes cancer cell death.

In terms of combined chemotherapy, Howell and colleagues synthesized multifunctional lipid nanoparticles (M-LMNs) by encapsulating MnO in mixed cation micelles.50 In vitro studies found that M-LMNs which had been loaded with doxorubicin (Dox) or plasmid DNA was efficiently ingested by Lewis Lung Cancer (LLC1). Following intranasal administration, M-LMNs were preferentially aggregated in the lung, while MRI and release of DNA and Dox could be simultaneously performed. This suggests great potential in the treatment of lung cancer. MnSO4-terminated mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) were calcined to obtain USMO@MSNs nanocrystals with adjustable pore sizes. The USMO@MSNs pore size was adjusted to 1.42 nm to match the chemotherapeutic drug Dox (1.37 nm), while the loading capacity was 456 mg/g. In the weak acidic environment of tumors, a simultaneous release of Mn2+ and Dox enabled real-time monitoring of the chemotherapy efficacy of Dox by MRI.51 Abbasi et al co-loaded the anticancer drug docetaxel (DTX) and MnO nanoparticles into an amphiphilic polymer which contained fluorescent dyes.52 The longitudinal relaxation (r1=2.4 mM−1s−1) of the probe was 2.7 times higher than that of MnO NPs. In contrast, fluorescence imaging had a positive long-term effect and could effectively load and sustain DTX, reducing the dose of drug needed to inhibit the growth of human breast cancer cells by 3–4.4 times.

In terms of photothermal therapy, MnO-coated carbon nanotubes (MWNTs-MnO-PEG) were used for the photothermal therapy of metastatic tumors. In order to examine the therapeutic effect of the nanotheranostic agent, it was co-incubated with A549 (human lung cancer) cells, after which it was found that under the laser irradiation of 3 w/cm2, almost no cells survived and typical cells were not significantly reduced. Lymph nodes (LNs) metastatic mouse model of A549 cells was used for in vivo studies. The surface temperature of lymph nodes increased rapidly from 25.28°C to 55.64°C within 5 mins under laser irradiation, while the surrounding typical tissues did not increase significantly.53 Similarly, Xiang et al encapsulated MnO with carbon nanospheres to obtain MnO@CNSs (CNSs) with MR imaging and photothermal therapy performance.14 In order to enhance the phototherapy effect, Zhou and colleagues synthesized a mitochondria-targeted multifunctional nano-photosensitizer (IR808@MnO NP), utilizing IR808 as a tumor-targeting ligand. Under laser irradiation, IR808 converts O2 to highly toxic 1O2 and also produces high heat. The tumors of MCF-7 nude mice treated with IR808@MnO NPs were completely attenuated under 808 nm near-infrared light.54

Mn3O4-Based Nanoparticles In Tumor Diagnosis And Therapy

The development of Mn3O4 NPs as MR CAs has also received extensive attention from researchers. In Mn3O4 NPs, Mn exhibits a mixed valence of +2 and +3. Compared with divalent manganese ions, higher valence states of Mn tend to exhibit lower effective T1 relaxation due to fewer unpaired electrons and less electron spin relaxation time. However, high-valent manganese ions can be activated in an intracellular reducing environment by GSH, while Mn ions are generated to increase the T1 relaxation rate.55 Thereby, a redox-activated T1 magnetic resonance CA can be designed.

Mn3O4 As Contrast Agents In Magnetic Resonance Imaging

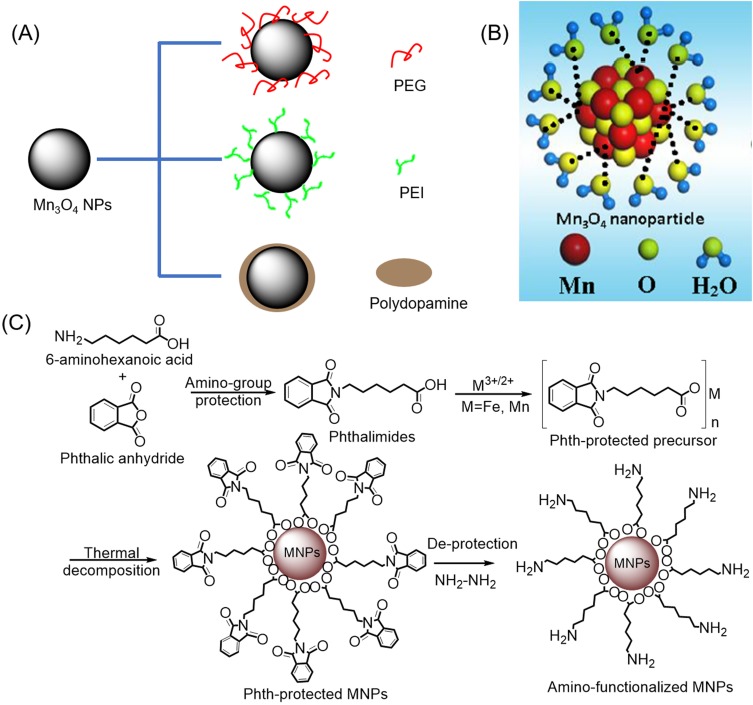

In recent years, multiple Mn3O4-based nanoplatforms have been developed for MRI as T1 CAs. In particular, the improvement of Mn3O4 T1-relaxivity and biocompatibility through different surface modifications has attracted interest from researchers. Encapsulation of hydrophobic nanoparticles by polymers – including PEG, PEI, and polydopamine (PDA) – is currently the most common modification strategy (see Figure 1A). Examples of the PEG-modified method include Hu et al’s design of the aptamer (AS1411) conjugated Mn3O4@SiO2 core-shell nanoprobes which was used for targeted T1-MRI in mice with human cervical cancer, after which the in vivo quantitative biological distribution and the toxicity of the probe were evaluated.56 Probes with a T1-relaxivity of 0.53mM−1s−1 were modified on the surface of SiO2 shelly by PEG to improve their biocompatibility. Yang and colleagues synthesized monodisperse manganese oxide NPs with a coating of silica (abbreviated as Mn3O4@SiO2) via pyrolysis at the high temperature and were aminated through the use of silylation.57 PEG was coupled to an Mn3O4@SiO2 surface via the amino-group attachment, followed by chemical grafting of targeting ligand FA to PEG. The final nanoprobes demonstrated good colloidal stability in RMPI plus 10% fetal bovine and exhibited the ability to target T1 magnetic resonance imaging in HeLa cells and HeLa animal tumor models overexpressing FA receptors. Wang and coworkers synthesized antifouling manganese oxide NPs using the solvothermal method in the presence of trisodium citrate, after which they modified the surface with PEG and L-cysteine.58 The prepared NPs had a high T1-relaxivity of 3.66 mM−1s−1 at 0.5 T, good aqueous solution dispersibility, good colloidal stability, and good biocompatibility. More crucially, the modification of L-cysteine allowed NPs to have a longer blood circulation time (half decay time of 28.4 hours) than those without the L-cysteine modification (18.5 hours) as well as reduced macrophages cellular uptake. This allowed NPs to be utilized as effective CAs for enhancing tumor T1-weighted MRI.

Figure 1.

(A) Common modification strategy for improving the T1 relaxation rate and biocompatibility of Mn3O4 NPs. (B) Schematic illustration of the interaction between Mn3O4 NPs synthesized by liquid laser ablation and water. Reproduced from Xiao J, Tian XM, Yang C, et al. Ultrahigh relaxivity and safe probes of manganese oxide nanoparticles for in vivo imaging. Scientific Reports. 2013;3:3424.63 (C) Synthetic route to amino-functionalized MNPs based on a protected metal-organic precursor. Reprinted with permission from Hu H, Zhang C, An L, et al. General protocol for the synthesis of functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for magnetic resonance imaging from protected metal-organic precursors. Chemistry. 2014;20(23):7160–7167.64 Copyright © 2014 John Wiley and Sons.

Abbreviation: MNPs, magnetic nanoparticles.

PEI is another type of polymer which is commonly used for surface modification. For example, Luo et al reported that PEI-coated Mn3O4 NPs which had been conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FI), PEGylated FA and PEG monomethyl ether in turn were used for targeted tumor in vivo MRI.59 Moreover, these authors believe that the PEI-coated Mn3O4 NPs can be modified by PEI along with other biomolecules for multimodal biomedical imaging applications. In order to obtain T1 magnetic resonance CAs with higher r1 relaxivity for positive MRI of biological systems, Sun and colleagues proposed the construction of hybrid alginate (AG) nanogels loaded with Mn3O4-PEI nanoparticles.60 Additionally, the hybrid AG/PEI-Mn3O4 with a high r1 relaxation rate of 26.12 mM−1s−1 at 0.5 T were approximately 19.5 times higher than PEI-Mn3O4 NPs. Moreover, the AG/PEI-Mn3O4 NGs had a longer blood circulation time and better tumor MRI performance in vivo than the PEI-Mn3O4 NPs.

At present, both PEG and PEI modification strategies are relatively mature. However, the PEG-modified strategy creates a thick hydrophobic hydrocarbon coating shell that has the potential to hinder chemical exchange between protons and magnetic ions, resulting in a relatively low T1 relaxation rate. An alternative strategy is to use small molecules such as sodium citrate (SC) instead of oleic acid or oleylamine on surfaces of hydrophobic nanoparticles. However, the heating conditions required for the reaction may unfortunately result in the oxidation of Mn2+ to Mn3+ ions. Since Mn3+ ions exhibit both lower unpaired electrons and significantly shorter electron relaxation times than Mn2+ ions, they are not sufficient for achieving efficient water proton exchange and reducing T1 relaxation of MONs. This means it is necessary to find an optimized surface modification scheme to improve the T1 relaxation rate of MONs. Lei and co-workers designed new Mn3O4 nanocubes (MOC), which they transferred to aqueous media via dopamine derivatives.8 The optimized surface endows the MOC a high r1 value (11.76 mM−1s−1 at 0.5 T) and a low r2/r1 ratio (1.75), avoiding the interference of T2-weighted imaging on T1-weighted imaging. Importantly, a reasonably designed pH-induced charge-switching surface can be charged negatively in the blood and positively at the tumor site. This unique function is able to improve the circulation behavior of the intelligent T1 CA in the blood and increase the uptake of cancer cells, thus realizing the accurate detection of solid tumors. On this basis, Lee and colleagues systematically studied the effects of various end-capping ligands such as carboxylate, alcohol, mercaptan, and amine with different anchoring groups on the surface functionalization of hollow manganese oxide nanoparticles (HMONs) to enhance T1 relaxation.61 Among all those studied, carboxylate-anchored ligands showed a significant increase in magnetization when capped on the surface of HMONs. In contrast to previous assumptions about the accessibility of surface Mn2+ ions to water molecules, Lee et al suggest that capping-induced magnetization in HMONs is the cause of enhanced relaxation (r1) values. In addition, in vivo imaging of oleate-terminated HMONs has been demonstrated in the brains of mice.

Guo and colleagues reported a liver T1-weighted MRI CA with good biocompatibility and a high T1 relaxation rate (r1=11.6 mM−1s−1 at 3.0 T), while in vivo experiments indicated that the liver signal of mice increased by 50.1% four hours after injection with the CA.62 This CA was synthesized using a two-step process; after dehydration and aromatization under hydrothermal conditions, caramelized carbon nanoparticles (CNPs) were prepared from glucose and utilized as self-sacrificing templates to deposit ultra-thin manganese oxide nanosheets from the redox reaction between CNP and KMnO4. The afore-mentioned manganese oxide-based nanoprobes were synthesized using a two-step or a multi-step method. In contrast, Xiao et al proposed a one-step method for the preparation of ligand-free Mn3O4 NPs using liquid laser ablation.63 The prepared Mn3O4 NPs directly interact with water molecules without modification (see Figure 1B). In addition, MTT assay indicated that the cytotoxicity of Mn3O4 NPs was negligible. Immunotoxicity assessment showed that the Mn3O4 NPs slightly stimulated the immune response system, but there was no significant difference between Mn3O4 NPs and commercial MRI CA Gd-DTPA, and the immune response was accepted by the body. Systematic studies of intrinsic toxicity have shown that Mn3O4 NPs with a high relaxation rate of 8.26 mM−1 s−1 at 3T have satisfactory biocompatibility in vitro and in vivo. The T1-weighted MR images showed that the signal of xenograft tumors was enhanced significantly after 30 mins of intravenous injection of Mn3O4 NPs. Hu and colleagues developed a simple, universal, cost-effective strategy for synthesizing water-soluble and amino-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles through the thermal decomposition of metal-organic precursors protected by phthalimide, followed by deprotection (Figure 1C).64 Obtained amino-functionalized Mn3O4 NPs have a particle size of 6.6 nm and a relaxation rate of 2.74 mM−1s−1, and when further conjugated with FA, these can specifically target cancer cells overexpressing FA receptors.

Mn3O4 As MR Contrast Agents In Bimodal And Multimodal Imaging

MRI has the advantages of high spatial resolution and no tissue penetration depth limitation, but its low temporal resolution and low sensitivity characteristics limit its clinical application. The combination of MRI and other modal imaging can provide more adequate functional and anatomical imaging information. In order to meet the challenges of clinical diagnosis, it is necessary to develop an imaging modal combination system that can combine the advantages of single modality. T1 CAs produce a bright signal but has inherently low magnetic resonance relaxation, while T2 CAs, especially superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles, have a high detection sensitivity for lesions but are prone to magnetic artifacts and inherent dark imaging features. Therefore, an MR CA that integrates T1 and T2 contrast capabilities will enhance the sensitivity and accuracy of magnetic resonance detection. Li and colleagues first synthesized branched PEI-coated Fe3O4@Mn3O4 NPs (Fe3O4@Mn3O4-PEI NCs) by using the one-pot hydrothermal method and then modifying hyaluronic acid (HA) on the surface of particles via PEI amine.65 The synthesized HA-modified Fe3O4@Mn3O4 NPs showed a relatively high relaxation of r2 (143.26 mM−1s−1) and r1 (2.15 mM−1s−1) for targeting T1/T2 dual-mode magnetic MRI of cancer cells overexpressing the CD44 receptor. CAs reported by Li are “always on” systems that exert MR contrast effects, regardless of whether or not they approach or interact with target cells in the organism, which Kim suggested may lead to a poor target-to-background ratio.66 Therefore, Kim and colleagues designed a polysorbate 80 surface-modified redox-responsive heterostructure (RANs) which was composed of a superparamagnetic Fe3O4 core and a paramagnetic Mn3O4 shell as a T1/T2 dual-mode MRI CA.66 In aqueous environments, the Mn3O4 shell protects the Fe3O4 core from water, resulting in a low CA T2 relaxation property. The Mn center is also confined to the Mn3O4 structure, resulting in low water accessibility and magnetic coupling with a superparamagnetic core. The contrast effect between T1 and T2 is the OFF state. While tumor cells accumulate CAs through enhanced penetration and retention (EPR) effects, the Mn3O4 shell reacts with abundant GSH in the cytoplasm to dissolve into Mn2+ ions. A great many high-spin Mn2+ ions and exposed Fe3O4 cores can be used as CAs for T1- and T2- MR, respectively. Redox activation produces a significant enhancement of T1 and T2 signal contrast (ON state). In addition, Kim and colleagues performed T1- and T2-weighted MR imaging in tumor-bearing mice using effective passive tumor targeting, demonstrating that these complexes can be utilized as dual-mode magnetic resonance CAs (see Figure 2A).

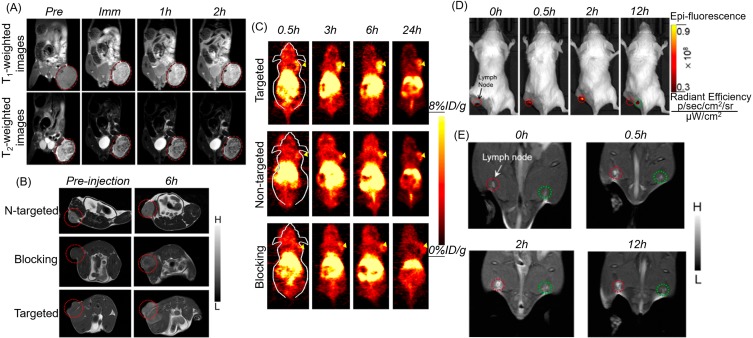

Figure 2.

(A) T1- and T2-weighted MR imaging of tumors with Fe3O4@Mn3O4 NPs. Reprinted from Kim MH, Son HY, Kim GY, Park K, Huh YM, Haam S. Redoxable heteronanocrystals functioning magnetic relaxation switch for activatable T1 and T2 dual-mode magnetic resonance imaging. Biomaterials. 2016;101:121–130.66 Copyright © 2016, with permission from Elsevier. Serial coronal T1-MRI imaging (B) and PET images (C) of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice after injection of 64Cu-NOTA-Mn3O4@PEG-TRC105, 64Cu-NOTA-Mn3O4@PEG, or 64Cu-NOTA-Mn3O4@PEG-TRC105 after a preinjected blocking dose of TRC105. Reproduced from Zhan Y, Shi S, Ehlerding EB, et al. Radiolabeled, Antibody-Conjugated Manganese Oxide Nanoparticles for Tumor Vasculature Targeted Positron Emission Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(44):38304–38312.1,32 Copyright © 2017 American Chemical Society. In vivo fluorescence imaging (D) and T1-MR imaging (E) of lymph nodes with Mn3O4@PEG-Cy7.5 NPs in BALB/c mice at different post-injection time points. Reprinted from Zhan Y, Zhan W, Li H, et al. In Vivo Dual-Modality Fluorescence and Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Guided Lymph Node Mapping with Good Biocompatibility Manganese Oxide Nanoparticles. Molecules. 2017;22(12):2208.70

Abbreviations: Pre, pre-injection; Imm, immediate; N-targeted, non-targeted.

Due to the high sensitivity of PET as well as the ultra-high spatial resolution and good soft tissue contrast of MRI, PET, and MRI dual-mode imaging can be currently used for clinical cancer detection, while the development of PET/T1-MRI bimodal mode probes best meets clinical demands. Zhu and colleagues synthesized PEI-coated Mn3O4 NPs through the solvothermal decomposition of acetylacetone manganese.67 PET/MRI bimodal probes were constructed using FA modification and 64Cu labeling on the surface of the amine groups Mn3O4 NPs. The obtained nanoprobes were successfully applied to PET/MRI imaging in small animals; compared with HeLa tumors blocked by folate receptors (FR), 64Cu-labeled Mn3O4 NPs showed a better tracer in HeLa tumors expressing FR 18 hrs after injection. In addition, FR-targeted Mn3O4 NPs showed accurate tumor T1-weighted MRI 18 hrs after injection. Zhan and team also studied PET/MRI dual-mode probes. They constructed 64Cu-labeled, antibody (TRC105)-modified Mn3O4 NPs for tumor vasculature targeted PET/MRI imaging (see Figure 2B and C).5 The anti-CD105 antibody TRC105 was the targeting ligand. CD105 has been shown to be overexpressed in many proliferating tumor endothelial cells, making it applicable for tumor diagnosis and meaning it has the potential to be used as a treatment via the use of nanomaterial.68 In vitro, in vivo and ex vivo experiments found good radioactivity and high specificity for the vascular marker CD105 of the Mn3O4 conjugated NPs (64Cu-NOTA-Mn3O4@PEG-TRC105).5 According to T1-enhanced imaging as well as in vivo toxicity studies of the Mn3O4-conjugated NPs, Zhan et al believed that Mn3O4 NPs can be used as a safe nanoplatform for long-term targeted tumor imaging, diagnosis, and even treatment. Based on this, these authors also proposed chelator-free zirconium-89 (89Zr, t1/2: 78.4 hrs) labeled Mn3O4 NPs ([89Zr]Mn3O4@PEG) for in vivo PET/MRI imaging and lymph node mapping.69 Before that, Zhan and colleagues developed an optical/MRI dual-mode imaging probe for in vivo bimodal imaging to guide lymph node mapping (see Figure 2D and E).70 They constructed a hybrid optical/MRI system based on PEG-coated Mn3O4 NPs conjugated Cy7.5. The obtained Mn3O4@PEG-Cy7.5 exhibited good colloidal stability as well as good biocompatibility.

Mn3O4 As MR Contrast Agents In Imaging-Guided Tumor Therapy

Cancer is a serious threat to human life and health, and the development of the theragnostics methods is seen by researchers as having great importance. Theragnostics is a burgeoning field in medical research which allows for simultaneous diagnostic and specific therapy to enhance overall patient treatment and safety.71 As illustrated in Figure 3, numerous research groups have used a variety of nanotechnology approaches to contribute to the development of theragnostic agents. Wang and colleagues demonstrated that Mn3O4 NPs have been dissociated in response to the redox reaction with GSH in an intracellular reducing environment.72 Based on this, they constructed a multifunctional mesoporous silica-based redox-mediated nanotheranostic system using Mn3O4 nanolids. The assembly process for this nanotheranostic system is as follows: firstly, mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSN) were prepared via sol-gel chemistry. MSN were then surface functionalized using carboxylic groups to ensure the loading of camptothecin (CPT) to nanochannels; finally, hydrothermally synthesized Mn3O4 NPs were treated using 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) and obtained Mn3O4-NH2 nanolids were capped to MSN-COOH structure loaded with CPT to avoid premature release of cytotoxic drugs. The r1 value of the system was calculated to be 13.39 mM−1s−1 at 3.0 T. Exposure of the nanotheranostic system, drug-loaded Mn3O4@MSN, to an intracellular GSH environment results in the dissolution of Mn3O4 nanolids and the intelligent release of drugs. In addition, the redox reaction dissociates the paramagnetic Mn3O4 NPs to Mn2+, which doubles the T1 signal (r1=25.17 mM−1s−1) and provides an additional opportunity to track therapeutic feedback. Zhang and co-workers designed an intelligent system for imaging diagnostics and chemotherapeutic applications.73 The highly integrated nanocomposite Dox-Mn3O4-SiNTs was assembled by uniformly distributing Mn3O4 NPs within mesoporous silicon nanotubes (SiNTs, 10–20 nm), while Dox was loaded into the mesoporous wall (~5 nm) of SiNTs. A series of in vitro and in vivo studies revealed that the Dox-Mn3O4-SiNTs nanotheranostic system has an excellent T1-weighted MRI performance (r1=1.72 mM−1s−1 at 3.0 T), which demonstrated a pH-dependent release behavior and exhibited remarkable therapeutic effects against both HeLa cells and cervical cancer xenografts.

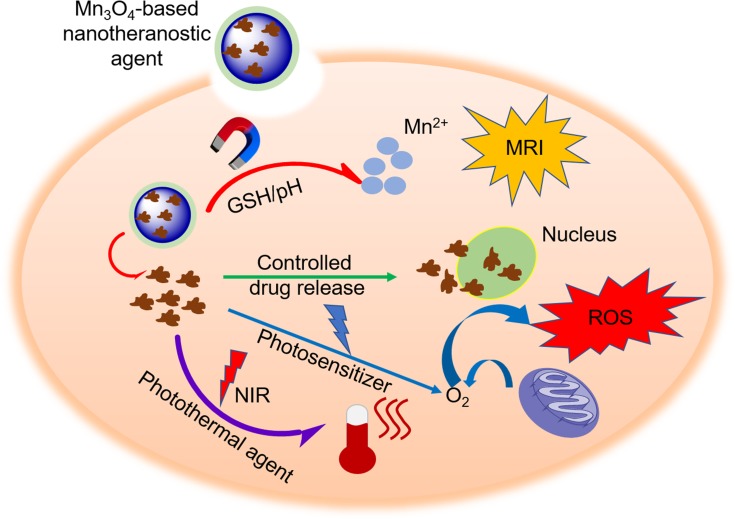

Figure 3.

The mechanism of Mn3O4-based nanotheranostic agents for imaging-guided chemotherapy/PDT/PTT and tumor MR imaging.

Abbreviations: NIR, near-infrared; ROS, reactive oxygen species; PDT, photodynamic therapy.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is an efficient clinical therapy in which cancer cells are damaged by reactive oxygen species produced by non-toxic photosensitizers which have been exposed to specific wavelengths.74 Imaging-guided PDT can provide more accurate tumor localization and reduce side effects on typical tissue. Nafiujjaman and colleagues developed a ternary hybrid probe, saved as dual imaging-guided PDT agent, which consisted of Mn3O4 and graphene quantum dots (GQD) linked by PDA and thiol-amine.75 Several stability studies of the hybrid system (GQD-PDA-Mn3O4) have indicated that the link between Mn3O4 and GQD can be maintained in different conditions, although partial fluorescence quenching occurs in GQD thanks to the presence of Mn3O4. While these nanoparticles exhibit good biocompatibility in dark conditions, subsequent laser irradiation can trigger GQD to generate effective fluorescent emissions and reactive oxygen species, killing cancer cells and leading tumor regression. Meanwhile, GQD-PDA-Mn3O4 nanoparticles also exhibited excellent optical and T1-weighted MRI capability. Ding and colleagues designed a multifunctional FA conjugated, drug (Dox)-loaded Mn3O4@PDA@PEG nanotheranostic agent to be utilized for MRI-guided synergetic chemo-/photothermal (PTT) therapy.76 The nanotheranostic agent with an ultrahigh T1-relaxivity of 14.47 mM−1s−1 at 1.2 T demonstrated excellent MRI ability in vitro and in vivo as well as providing overall information for tumor diagnosis and therapeutic effect monitoring. PDA can not only endow the nanotheranostics system with biocompatibility but can also act as a photothermal conversion agent for PTT and an anti-cancer drug carrier. NIR When the 808 nm near-infrared laser irradiation drug release was triggered, the nanotheranostics agent showed a significantly enhanced tumor synergistic effect, compared with both PTT and chemotherapy alone. Additionally, following the development of nanotheranostic agents, the nanotoxicity of agents has been challenged. Liu et al have developed an artificially induced degradation of ethylenediaminetetraacetic calcium disodium salt (EDTA)- and bovine serum albumin (BSA)-capped Mn3O4 NPs (MONPs-BSA-EDTA) as a novel, inorganic nanomaterial for T1/T2-MRI guided PTT.77 Due to the high electron spin and strong NIR absorption, Mn3O4 NPs not only act as a T1-T2 dual-mode MR contrast agent but also as a photothermal conversion agent. MONPs were degraded into free ultra-small Mn3O4 NPs and Mn2+ with the introduction of ascorbic acid. Moreover, Mn2+, which is considered toxic to the living system, can be captured by BSA coating on the particles and EDTA loaded thereon, thereby avoiding the nanotoxicity of the inorganic nanomaterial.

MnO2-Based Nanoparticles In Tumor Diagnosis And Therapy

It is well known that the growth and metabolism of tumor cells are not strictly regulated in the way that they are in typical cells, which results in the microenvironment of tumor tissues being rather different from typical tissues. On one hand, H2O2 is overproduced in malignant tumor cells and thus results in a significant increase in the level of H2O2 in a TME.78 On the other hand, upregulated glycolysis metabolism during tumorigenesis produces a large amount of lactic acid, resulting in a low pH value of TME.79 It has additionally been reported that GSH in tumor tissues is almost five times that of typical tissues and that GSH plays a key role in protecting cells from various harmful substances such as H2O2, superoxide, hydroxyl radical, and other reactive oxygen species.80 Hypoxia is a prominent feature of solid tumors which is often associated with tumor invasion, metastasis, and resistance to traditional therapies.81 This means that the high GSH levels and hypoxia characteristics of cancer cells have been shown to increase resistance to chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and photodynamic therapy (PDT). As reported, manganese dioxide (MnO2) has the ability to react with GSH to reduce Mn4+ to Mn2+. While consuming intracellular GSH, the Mn2+ produced can not only enhance T1-MRI but also undergoes a Fenton reaction with H2O2 to form a hydroxyl radical (·OH), the most harmful reactive oxygen species (ROS).80 Therefore, in recent years, research on manganese dioxide nanoparticles (MnO2 NPs) has ignited, owing to these nanoparticles’ excellent T1-weighted MRI capability and ability to respond intelligently to TME as a nanotheranostic agent.

MnO2 As Contrast Agents In MRI And Cellular GSH Detection

MRI plays a key role in clinical detection, especially soft tissue. Traditional magnetic resonance CAs tend to be “always on” regardless of whether they are close to or interact with the target cell, which may result in a poor signal-to-noise ratio. Recently, studies have found that MnO2 can enhance the contrast of magnetic resonance signals in response to endogenous stimuli such as pH, GSH (see Figure 4A). Based on this, many researchers have made deliberate achievements in the activatable magnetic resonance CAs of MnO2. Zhao and colleagues reported a dual-activatable fluorescence/MRI bimodal nanoprobe which was based on MnO2 nanosheet-Cy5 labeled aptamer nanoparticles for tumor cell imaging.82 In this dual-mode imaging system, MnO2 nanosheets act as a nanocarrier to deliver aptamer, a fluorescence quencher, as well as an intracellular GSH-activated T1/T2-MRI CA (see Figure 4C). When the aptamer does not target cells, neither the fluorescence signals nor the MRI contrast of nanoprobes were activated. Conversely, once the target cells exist, the binding of aptamers to their targets will lead to a decrease in the adsorption of aptamers on MnO2 nanosheets, resulting in partial fluorescence recovery (see Figure 4B), irradiation of target cell, and the promotion of endocytosis of nanoprobes to the target cell. Following endocytosis, GSH reduced MnO2 nanosheets to further activate the fluorescent signal and produce many Mn2+ ions suitable for MRI. Moreover, the reduced Mn2+ ions exhibited both 48-fold and 120-fold enhancements in the longitudinal relaxation rate r1 and the transverse relaxation rate r2 when compared to the MnO2 nanosheets. This platform promotes the development of various activatable fluorescent/MRI bimodal imaging for cells.

Figure 4.

(A) Schematic that MnO2 NPs enhance the magnetic resonance contrast under endogenous stimulation. (B) Optical (above) and fluorescent images (below) of MnO2 nanosheet−sgc8 nanoprobe to target cells. (C) T1- and T2-weighted MRI of MnO2 nanosheet solution treated with GSH. Reproduced with permission from Zhao ZL, Fan HH, Zhou GF, et al. Activatable Fluorescence/MRI Bimodal Platform for Tumor Cell Imaging via MnO2 Nanosheet-Aptamer Nanoprobe. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2014;136(32):11220–11223.82 Copyright © 2014 American Chemical Society. (D) Phosphorescence images and T2-weighted MR images of a tumor-bearing mouse and a NEM-pretreated tumor-bearing mouse after injected with Ru(BPY)3@MnO2 for 15 mins. Reproduced from Shi W, Song B, Shi W, et al. Bimodal Phosphorescence-Magnetic Resonance Imaging Nanoprobes for Glutathione Based on MnO2 Nanosheet-Ru(II) Complex Nanoarchitecture. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10(33):27681–27691.83 Copyright © 2018 American Chemical Society. (E) T1- and T2-MRI of tumors with Fe3O4@C@MnO2 NPs. Reproduced from Duan B, Wang D, Wu H, et al. Core–Shell Structurized Fe3O4@C@MnO2 Nanoparticles as pH Responsive T1-T2* Dual-Modal Contrast Agents for Tumor Diagnosis. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering. 2018;4(8):3047–3054.84 Copyright © 2018 American Chemical Society.

Abbreviation: NEM, N-ethylmaleimide.

For clinical diagnosis, in vitro evaluation of nanoprobes is not sufficient. Based on this, Shi and colleagues reported a GSH-activated Ru(BPY)3@MnO2 bimodule phosphorescence/MR imaging nanoprobe for the determination of GSH in vitro and in vivo (see Figure 4D).83 As previously described, MnO2 nanosheets are both phosphorescent quenchers and GSH-responsive MR CAs. After being triggered by GSH, MnO2 nanosheets can be rapidly reduced to Mn2+ ions, which leads to enhancement of the T1- and T2-weighted MR signals (r1 increased from 0.11 to 9.33 mM−1s−1, and r2 increased from 0.16 to 48.77 mM−1s−1 at 0.5 T) while recovering the phosphorescence of the Ru(II) complex. Since the enhancement factor of r2 (85 folds) is 2.6 times higher than that of r1 (305 folds), this means that when Ru(BPY)3@MnO2 NPs are used as T2-MR contrast agents, a higher signal-to-noise ratio can be obtained. The GSH concentration can be quantified by phosphorescence and MR. The time-gated luminescence (TGL) assay of GSH in human serum as well as the visualization of endogenous GSH in zebrafish and tumor-bearing mice in both phosphorescence and MR imaging modes confirmed that the prepared nanoprobes have good biocompatibility and fast response as well as a high sensitivity and selectivity to GSH. Moreover, Duan and colleagues constructed a core-shell Fe3O4@C@MnO2 nanoprobe via an in situ self-reduction method which was used as a pH-responsive T1-T2* dual-modal MRI contrast agent (Figure 4E).84 The release rate of Mn2+ ions in acidic PBS with pH of 5.0 is approximately 10 times that of pH 7.4, which promotes the release of synthesized nanoparticles in the acidic environment of tumors. Following intravenous injection of Fe3O4@C@MnO2 NPs for 24 hours, the T1 MRI signal in the tumor area was significantly enhanced by 127% compared with prior to injection. At the same time, the T2 MRI signal was weakened to 71%. Therefore, the Fe3O4@C@MnO2 NPs are able to significantly increase the accuracy of the diagnosis and can be expected to develop as a clinical, multi-diagnostic nanoplatform.

MnO2 As MR Contrast Agents In Imaging-Guided Tumor Therapy

MnO2 NPs For Enhanced Chemotherapy And MRI

Chemotherapy is a traditional cancer treatment which damages healthy cells while killing cancer cells. It has many side effects. Moreover, hypoxia, a major characteristic of most solid tumors, not only promotes the invasiveness and metastasis of malignant cells but is also associated with resistance to radiation and chemotherapy.85 This means that a major challenge for enhancing the therapeutic effects and minimizing the side effects of chemotherapy is the need to achieve on-demand drug release and alleviate tumor hypoxia. As previously reported, MnO2 nanoparticles have received extensive researcher attention due to their high reactivity to hydrogen peroxide for producing O2 and their response to pH decomposition into Mn2+, which can be used as MR CAs.

Many researchers have made significant contributions to the construction of MnO2-based smart drug delivery systems (see Table 2).51,80,86–95 Among these, Song and colleagues reported on Dox loading, HA-modified and mannan conjugated MnO2 nanoparticles (Man-HA-MnO2 NPs) for targeting 4T1 mouse breast cancer cell imaging and enhancing chemotherapy.87 The high accumulation of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) in hypoxic regions of solid tumor as well as the high reactivity of MnO2 NPs toward H2O2 led to simultaneous generation of O2 and the regulation of pH to effectively mitigate tumor hypoxia. In addition, HA not only serves as a target but can also reprogram anti-inflammatory, pro-tumor M2 TAM into pro-inflammatory, anti-tumor M1 macrophages to further enhance the resultant nanoparticles to reduce tumor hypoxia and regulate chemoresistance. At the same time, Mn2+ ions released by the reaction of Man-HA-MnO2 NPs with H2O2 significantly enhanced both the tumor imaging and the detection performance of T1 and T2-MRI. Inspired by the biological process of KMnO4 disinfection, Pan et al prepared a multifunctional BSA-MnO2 nanoplatform which had a uniform size of less than 10 nm, excellent colloid stability, and high T1 relaxation rate of 7.9 mM−1s−1 at 0.5 T by drug–substrate interaction strategy.90 The BSA-MnO2 nanoprobe can not only be used as a high-performance MRI agent for tumor and renal imaging but also as a MRI-guided photothermal and chemotherapeutic agent when loaded with indocyanine green and paclitaxel, respectively. Pan’s work provides a new method for the development of therapeutic agents. In Zhang’s study, MnO2/Dox-loaded albumin nanoparticles (BMDN) were fabricated as a theragnostic agent for cancer MRI and a reversing multidrug resistance (MDR) tumor chemotherapy.91 MDR hinders the effects of chemotherapy. At present, nanocarriers are a potential means for overcoming tumor MDR,96 while albumin has been extensively studied as a hopeful drug carrier for nanocarrier construction due to both its excellent biocompatibility and low immunogenicity. Additionally, albumin can promote the delivery of BMDN to tumor cells, enhance cellular uptake, achieve on-demand drug release, and reduce tumor hypoxia through interaction with albumin receptors overexpressed on cancer cells. The weak acidic response of BMDN promotes the release of Mn2+, resulting in enhanced T1-weighted imaging both in vitro and in vivo.

Table 2.

Summary Of The Properties Of Nanoplatforms Based On Manganese Oxide-Enhanced Chemotherapy Reported In Recent Years. Classification Of Materials As A pH Response Does Not Preclude Its Response To Other Features Of The Tumor Microenvironment And Vice Versa. Classification Is Based On Evidence In Each Reference

| Nano-Structure | Responsive | Drug | r1(r2) Off (mM−1s−1) | r1(r2) On (mM−1s−1) | B (T) | Tumor Model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEG-MnO2 nanosheets | pH | Dox | 0.007 | 4.0 | \ | 4T1 tumor-bearing nude mice (T1-MRI) MCF-7/ADR cancer cells (chemotherapy) |

86 |

| Man-HA-MnO2 NPs | H2O2/pH | Dox | 0.12 (0.41) | 7.96 (45.05) | 9.4 | 4T1 tumor-bearing mice | 87 |

| MnO2/HA nanosheets | Redox/pH | CDDP | 1.3417 | 0.3803 | 0.5 | A549 tumor-bearing mice | 88 |

| MnO2-PEG-FA nanosheets | Redox/pH | Dox | 0.38 | 2.26 | 0.5 | Hela tumor-bearing mice | 89 |

| BSA-MnO2 NPs | \ | PTX | 7.9 (BSA-MnO2) 13.9(BSA-MnO2-PTX) |

\ | 0.5 | 4T1 tumor-bearing mice | 90 |

| BSA-MnO2 NPs | pH | Dox | 4.762 (BSA-MnO2) 11.794 (BSA-MnO2-Dox) |

\ | 1.5 | MCF-7/ADR tumor-bearing mice | 91 |

| MnO2 NPs | H2O2/pH | ANPs-PTX | 0.13 | 2.34 | 7 | CT26 tumor-bearing mice | 92 |

| HMSNs@MnO2/apt NPs | GSH/pH | Dox | 1.68 | 9.25 | 3 | NHDFs and HeLa cells | 93 |

| MS@MnO2 NPs | H2O2/GSH | CPT | 0.50 | 6.91 | \ | U87MG tumor-bearing mice | 80 |

| UCNPs@MnO2 NPs | GSH/pH | Dox | 0.41 | 4.48 | \ | HeLa cells | 94 |

| NaYF4:Yb, Tm@NaYF4@hmSiO2 @MnO2@DOTA NPs |

pH | Dox | 0.112 | 1.137 | 3 | Hela tumor-bearing mice |

95 |

Abbreviations: Man, mannan; HA, hyaluronic acid; NPs, nanoparticles; CDDP, cisplatin (cis-diamminedichloroplatinum); BSA, bovine serum albumin; PTX, paclitaxel; ANPs-PTX, albumin-bound paclitaxel nanoparticles; HMSNs, hollow mesoporous silica nanoparticles; apt, aptamers; GSH, glutathione; MS, mesoporous silica; CPT, camptothecin; UCNPs, upconversion nanoparticles; hmSiO2, hollow mesoporous silica; DOTA, Tetraxetanum.

In order to achieve simultaneous accurate diagnosis and effective treatment of hypoxic tumors, Song and colleagues designed and synthesized a versatile rattle-structure nanotheranostic agent, with an up-conversion nanoparticle (UCNP) as the core wrapped in hollow mesoporous silica, Dox loaded in the cavity, a hypoxia-sensitive MnO2 nanosheet enriched on the mesopores, as well as PEG and DOTA ligands conjugated onto the outer surface of the nanoparticles.95 MnO2 nanosheets can be degraded to Mn2+ ions in various acidic TME caused by varying degrees of hypoxia, while the resulting Mn2+ ions can be captured by DOTA for real-time T1-MRI diagnosis of hypoxic tumors. In addition, the nanoplatform can on-demand release Dox and supplement O2 to result in both normoxia- and hypoxia-sensitive chemotherapy with a single drug.

Recently, efforts have been made to develop ROS-based cancer therapeutic strategies, particularly chemodynamic therapy (CDT) which uses iron-mediated Fenton reactions.97 Unfortunately, overexpressed GSH in cancer cells has the ability to clear ·OH, which greatly reduces CDT efficacy. Based on this, Lin et al were the first to report a self-reinforced CDT nanomaterial based on MnO2, which proposes Fenton-like Mn2+ delivery capacity as well as GSH depletion characteristics.51 These authors synthesized camptothecin-loaded, MnO2-coated mesoporous silica NPs (MS@MnO2-CPT) for MRI-monitored chemo-chemodynamic synergistic cancer treatment. Once cancer cells take up the MS@MnO2-CPT NPs, the MnO2 shell reacts with GSH to reduce Mn4+ ions to Mn2+ ions. While consuming endogenous GSH in the physiological medium rich in HCO3−, the produced Mn2+ not only enhances T1-MRI but also undergoes a Fenton reaction with H2O2 to form·OH and so enhance CDT.

MnO2 NPs For Enhanced Photodynamic Therapy And MRI

PDT is a non-invasive tumor replacement therapy in which a photosensitizer reacts with the surrounding oxygen to generate a highly active singlet oxygen and so attack internal biomolecules (such as DNA and biological membrane) under laser irradiation at a specific wavelength, resulting in damage to or death of cells.74 Unfortunately, the hypoxic environment of tumors98 along with the ability of overexpressed GSH to scavenge ROS80 and the short diffusion length of lasers99 are all obstacles to the clinical application of PDT. As a result of its typical physicochemical properties, the emerging two-dimension MnO2 nanosheets have been studied extensively in enhanced PDT. Crucially, based on the fact that MnO2 nanosheets can react with intracellular GSH to reduce the amount of GSH, Meng and colleagues designed and synthesized an aptamer-conjugated, Dox and Chlorin e6 (Ce6)-loaded, MnO2 nanosheets gated, two-photon dye-doped mesoporous silica nanoparticle for GSH-responsive fluorescence/MR bimodal cellular imaging as well as targeted chemotherapy and PDT.100 Additionally, in acidic and H2O2-rich tumor microenvironments, MnO2 nanosheets can be reduced to Mn2+ while O2 can be formed by the following formula, thus reducing hypoxia in the tumor site:101

|

|

Many researchers have made achievements in this area. Sun and colleagues constructed a smart pH/H2O2-responsive nanoplatform to be utilized for self-enhanced upconversion luminescence/MR/CT-guiding diagnosis and PDT treatment.102 This was based on a core-shell-shell structure of Ce6-sensitized up-converted nanoparticle-loaded honeycomb manganese oxide (hMnO2) nanospheres. Liu et al synthesized BSA-stabilized MnO2 nanostructures (BMnNSs), after which the photosensitizer 2-devinyl-2-(1-hexyloxyethyl) pyropheophorbide (HPPH) was conjugated onto BMnNSs surface.103 Owing to the generation of O2 following the reaction of MnO2 nanosheets with H2O2, the BMnNSs-HPPH showed a significantly enhanced tumor growth inhibition when compared with HPPH. Similarly, in order to overcome hypoxia and improve the photodynamic effects of bladder cancer, Lin and colleagues prepared HSA-MnO2-Ce6 NPs.104 The O2 production of NPs in vivo and in vitro was investigated, while the oxygen content of the in situ bladder cancer increased 3.5-fold following injection of HSA-MnO2-Ce6 nanoparticles when compared with pre-injection.

To prevent the premature release of photosensitizer (PS) and increase oxygen concentration in solid tissues, Ma and colleagues developed an acidic H2O2-response core-shell O2-elevated PDT nanoplatform through the use of a MnO2 shell to encapsulate a SiO2-methylene blue core with a high PS payload.105 Following the intravenous injection of nanoparticles, the external MnO2 shell stops PS leaking into the blood until it reaches tumor tissue, avoiding phototoxicity to healthy cells. Acidic H2O2 in the tumor environment triggers the formation of O2 by MnO2 while it reduces Mn4+ to Mn2+, meaning it can selectively perform MRI while monitoring tumor therapy. For pH/H2O2-driven fluorescence/MR dual-mode guided cancer PDT, Liu constructed a black phosphorus/MnO2 nanoplatform.106 In order to endow the specificity of nanoparticles for targeting tumors to enhance PDT, as reported by He, the AS1411 aptamer was anchored to the surface of large pore silica nanoparticles in which MnO2 nanoparticles were grown in situ.107 Zhu et al constructed a multifunctional therapeutic nanoplatform through the integration of the nanoscale metal-organic framework (NMOF), BSA, sulfadiazines (SDs), and MnO2 into a system.108 Porphyrins not only participate in the formation of NMOF as organic ligands but also act as photosensitizers. BSA is an ideal vehicle for endowing the multifunction nanoplatform with excellent biocompatibility and long circulation. SDs were used to provide active targeting of overexpressed carbonic anhydrase IX (CA IX) in tumor cells. In addition, the nanoplatform can alleviate tumor hypoxia by downregulating CA IX and catalyzing H2O2 to produce O2, which significantly enhances the PDT effect. This can be confirmed by the photocytotoxicity of 4T1 cells and the reduced tumor volume. PDT is an effective strategy for eliminating primary tumors, but its effect on metastasis and recurrence is not obvious. In order to achieve oxygen-boosted immunogenic PDT in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC), Liang and colleagues designed a core-shell gold nanocage@manganese dioxide (AuNC@MnO2) nanoparticle as a tumor microenvironment pH/H2O2 responsive oxygen generator and a NIR-triggered ROS producer.109 The nanoplatform does not just achieve fluorescence/PA/MR multimodal imaging-guided O2-enhanced PDT for destroying primary tumors effectively, but can also induce immunogenic cell death with the release of a damage-related molecular pattern, subsequently inducing dendritic cell maturation and effector cell activation, thus arousing the systematic antitumor immune response against mTNBC, work which has made it possible to prevent tumor metastasis.

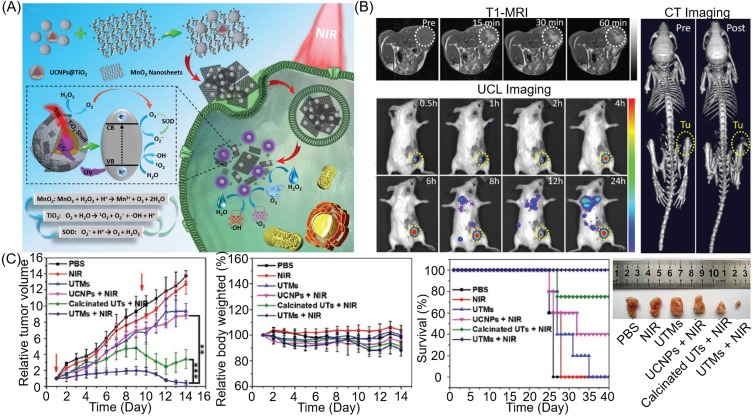

Hao110 and Chu101 state that once the NPs of the MnO2 shell-coated photosensitizer are taken up by the tumor cells, the endogenous H2O2 is catalyzed by the MnO2 shell to produce O2. At the same time, overexpressed GSH promotes the degradation of MnO2 to Mn2+ ions to enhance MRI. Fortunately, the reduction in GSH and generation of O2 demonstrate synergistic enhanced PDT to improve antitumor efficacy in vitro and in vivo. The TME-responsive MnO2 in this nanoplatform can generate oxygen to alleviate hypoxia. In addition, enhanced photosensitizer yield and elevated oxygen are conducive to the ultimate therapeutic effect. Based on the MnO2 shell-enhanced PDT, Hu et al111 and Xu et al112 loaded Dox on the designed nanoplatform to realize a tumor microenvironment-responsive multimodal imaging-monitoring chemo-photodynamic therapy. In contrast, Bi and colleagues used an MnO2 shell as the carrier of platinum(IV) (Pt(IV)) prodrugs, while intracellular GSH simultaneously reduced MnO2 and Pt(IV) prodrugs to achieve GSH-responsive MRI and drug release.113 Interestingly, as illustrated in Figure 5A, Zhang and colleagues developed nanocomposite, upconversion nanoparticles (UNCPs)@TiO2@MnO2, to overcome the deficiencies of PDT with insufficient oxygen, inefficient ROS generation, and low light penetration depth.114 Once the nanoplatform was taken up by tumor cells, intracellular H2O2 was catalyzed by MnO2 to generate O2 in situ. Given the degradation of MnO2 and 980 nm NIR laser irradiation, exposed UNCPs can effectively convert NIR into ultraviolet light to activate TiO2, after which they catalyze the splitting of H2O to produce toxic ROS (1O2 and ·OH) for deep tumor treatment. In addition, the by-product of water-splitting, superoxide anion radicals (O2˙ˉ), can be catalyzed using intracellular superoxide dismutase (SOD) to generate more H2O2 and O2. This cyclic reaction allows both O2 and ROS to be regenerated by decomposition of MnO2, while upconversion luminescence and MR imaging are activated in turn, which can significantly improve PDT efficiency and tumor imaging ability (see Figure 5B and C). This has great potential in antitumor.

Figure 5.

(A) Schematic illustration of (UNCPs)@TiO2@MnO2 NPs for O2 self-supplemented and ROS circulating amplified PDT. (B) T1-MR/UCL/CT imaging of tumors with (UNCPs)@TiO2@MnO2 NPs. (C) The treatment effect of PDT with (UNCPs)@TiO2@MnO2 NPs. Reprinted with permission from Zhang C, Chen WH, Liu LH, Qiu WX, Yu WY, Zhang XZ. An O2 Self-Supplementing and Reactive-Oxygen-Species-Circulating Amplified Nanoplatform via H2O/H2O2 Splitting for Tumor Imaging and Photodynamic Therapy. Advanced Functional Materials. 2017;27(43):1700626.114 Copyright © 2017 John Wiley and Sons.

Abbreviations: UCL, upconversion luminescence; UCNPs, upconversion nanoparticles; UTMs, UCNPs@TiO2@MnO2; UTs, UCNPs@TiO2 core–shell–shell nanoparticles.

MnO2 NPs For Enhanced Photothermal Therapy And MRI

Photothermal therapy (PTT) is a new cancer treatment research technology which uses nanomaterials to convert near-infrared light energy into thermal energy ablation tumor.115 The therapy has attracted great attention in recent years due to its remarkable advantages, such as being noninvasive, leading to a rapid recovery time and high space-time control.116 Imaging probes are a key component of theragnostics which can report the presence of tumors as well as monitoring and evaluating therapeutic effects.117 MnO2, a magnetic resonance CA which responds to tumor microenvironment, is widely used in MRI-guided PTT.

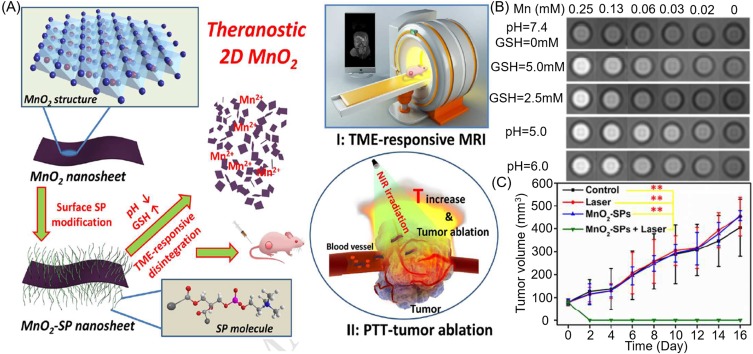

Pan and colleagues synthesized a nanotheranostic agent for the cross-linking of indocyanine green on BSA-stabilized MnO2 surface (BMI).90 This BMI has an ultrahigh T1 relaxation rate of 70.6 mM−1s−1 at 0.5 T. Tumors of 4T1 cells-bearing Balb/c mice completely disappeared after 13 days of intratumoral administration and irradiation with 808 nm laser at a power of 0.5 W cm−2. For the first time, as shown in Figure 6A, Liu and colleagues proposed that ultrathin 2D MnO2 nanosheets have T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging capabilities of pH and redox response (see Figure 6B), and the ultrathin 2D MnO2 nanosheets also have inherently high photothermal conversion capability (η: 21.4%), in vitro and in vivo photothermal experiments systematically demonstrated that 2D MnO2 nanosheets have a high PTT efficiency in response to external near-infrared radiation for inhibiting tumor growth (see Figure 6C).118 In view of the excellent physicochemical properties of MnO2 as well as the large size of 2D MnO2 nanosheets, Fu et al reported a simple method for the growth of MnO2 shells on various cores which are mediated by cationic polyelectrolytes.119 The Cu2-xSe@MnO2 nanoparticles which have been synthesized by this method show triple-enhanced magnetic resonance contrast in the tumor environment, while the Cu2-xSe core has strong absorption in second near-infrared (NIR II) window, demonstrating excellent PTT effect in vivo and in vitro. Peng and colleagues developed Prussian blue/MnO2 hybrid nanoparticle of less than 50 nm using a one-pot method for PA/T1/T2 MR three-mode imaging-guided oxygen-regulated PTT in breast cancer.24 In view of the heterogeneous heat distribution in tumor tissues120 and the rapid heat shock protein (HSP) production121 which leads to PTT treatment resistance and reduced therapeutic efficacy, it is urgent that we design versatile nanoparticles which can integrate PTT with other therapies for synergistic treatment. Based on this, Jin et al constructed a novel theragnostic agent, Co−P@mSiO2@Dox−MnO2, for pH-activated T1/T2 dual-modal magnetic MRI-guided chemo-photothermal synergistic therapy both in vitro and in vivo.122 In a weak acidic tumor environment, the MnO2-gated dissolution not only enhanced T1-weighted MRI but also achieved on-demand drug release. This stimuli-responsive nanoagent provided more accurate diagnostic information, hugely improved the therapeutic effect and effectively reduced side effects.

Figure 6.

(A) Schematic illustration of synthetic procedure for MnO2-SPs nanosheets and their specific functions for tumor theranostics with TME sensitivity. (B) T1-weighted MR imaging of MnO2-SPs in buffer solution at differing pHs (6.0 and 5.0) and differing GSH concentrations (2.5 and 5.0 mM) following incubation for 2 hours at 37°C. (C) Time-dependent tumor-size curves following different treatments. Reproduced from Liu Z, Zhang SJ, Lin H, et al. Theranostic 2D Ultrathin MnO2 Nanosheets with Fast Responsibility to Endogenous Tumor Microenvironment and Exogenous NIR Irradiation. Biomaterials. 2018;155:54–63.118 Copyright © 2017, with permission from Elsevier.

Abbreviation: SP, soybean phospholipid.

In terms of chemo-photothermal synergistic therapy, Li and colleagues designed poly(ethylene glycol)thiol (PEG-SH) modified CuS-Au-MnO2 ternary Janus nanoparticles (JNPs).123 In these ternary JNPs, the pH-responsive mesoporous MnO2 acted not only as a T1 magnetic resonance CA but also as a carrier for the hydrophobic drug celastrol (CST). In addition, Au endowed ternary JNPs with CT imaging capability, and the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) coupling effect of CuS surface and Au core enabled it to perform hyperthermia at 1064 nm in the NIR-II window to ablate deep tissue tumors. Similarly, Zhang and colleagues reported a GSH-activated nanoagent, SiO2@Au@MnO2-Dox/AS1411, for magnetic resonance/fluorescence imaging-guided synergistic chemo-photothermal therapy for hypoxic solid tumors in vitro and in vivo.124 An example of this combination of photothermal therapy and radiotherapy comes from Yang et al, who designed WS2-based nanocomposites with iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) and MnO2 shell via self-assembly.125 Here, MnO2 was used as a pH-activated T1 CA and IONPs as a pH-inert T2 CA to achieve tumor pH-responsive MRI. The strong NIR absorption of WS2 enabled photoacoustic imaging capacity, while the near-infrared and X-ray absorption of WS2 were performed for PTT and enhanced radiotherapy, respectively. More crucially, MnO2 catalyzed overexpression of H2O2 produced O2 to alleviate tumor hypoxia and so enhance therapeutic effects. Cao and colleagues prepared MnO2/Cu2-xS-siRNA nanoparticles by loading Cu2-xS onto the surface of MnO2 nanosheets and then modifying them with HSP 70 siRNA.126 Once NPs were taken up by tumor cells, MnO2 nanosheets were reduced to Mn2+ ions which enhance the MRI contrast and initiated the decomposition of H2O2 to O2 to alleviate tumor hypoxia. The NIR absorption of Cu2-xS can be used for PA and photothermal (PT) imaging. Under a single NIR laser irradiation, NPs exhibited a three-mode imaging-guided enhanced PTT/PDT due to siRNA-mediated blockade heat shock response as well as MnO2-related amelioration of tumor hypoxia.

MnOx-Based Nanoparticles In Tumor Diagnosis And Therapy

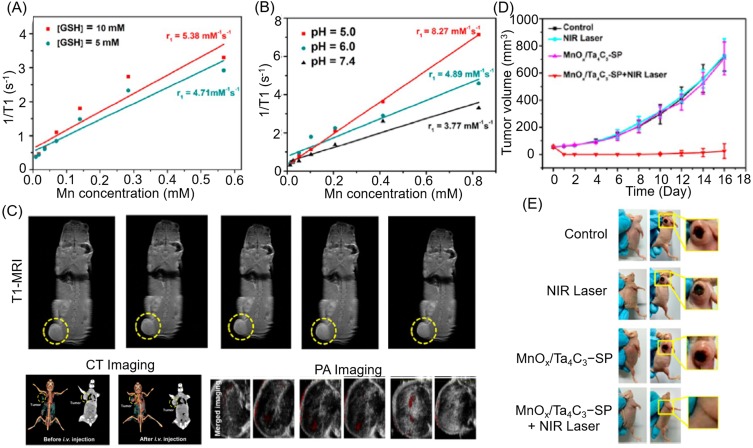

The oxidation state of manganese oxide can be distinguished using classical material science characterization techniques such as X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and so on. However, when the size of the material reaches the nanoscale, the broadening and weakening of the peak means that this characterization becomes extremely challenging. Therefore, some researchers described the nanostructures simply as MnOx to avoid inaccuracies.26 Rosenholm and colleagues modified amorphous MnOx with PVP and poly(acrylic acid) (PAA) to bring a negative charge to the surface (−25.7 ± 1.47 mV), while the hydrodynamic properties and biocompatibility were found to be significantly better than crystallization (MnO). Additionally, the relaxation time of the nanoprobe was approximately 10 times lower than that of the crystalline particles.127 Ren and colleagues used MnOx coated superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles as gates to control the CPT release from mesoporous silica and so achieve the TME-responsive T1/T2 dual-mode MRI-guided pancreatic cancer chemotherapy both in vitro and in vivo.128 Similarly, Gao and colleagues labeled technetium-99 (99mTc) on the surface of the MnOx-based mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MnOx-MSN) to integrate SPECT and MRI imaging modalities for both excellent sensitivity and high spatial resolution.129 The radiolabeling yield was as high as 99.1±0.6%, while the r1 value of the nanostructures could reach 6.60 mM−1s−1 as a result of the pH-responsive nature of MnOx-MSN. Additionally, the drug loading rate of MnOx-MSN to Dox was as high as 382 mg/g, while the degradation of MnOx in a weak acid environment triggers on-demand drug release. Zhang and colleagues ingeniously integrated MnOx NPs into hollow mesoporous carbon nanocapsules via an in situ framework redox method. In the weak acidic environment, the longitudinal relaxation of pH-sensitive MnOx NPs increased 52.5 times to 10.5 mM−1s−1.130 The carbonaceous framework could not only react with MnO4 to form MnOx NPs in situ but could also connect to the aromatic drug molecules through π-π stacking. Drug release behavior which was triggered by different pH and high intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) systematically confirmed the findings of pH-/HIFU-triggered Dox on-demand release as well as enhanced cancer cell chemotherapy. In contrast, Dai and colleagues grew MnOx nanoparticles in situ on the surface of tantalum carbide (Ta4C3) MXene nanosheets and created further surface organic modification by soybean phospholipids (SP) for three-mode imaging-guiding PTT.131 Similarly, the integrated nanoparticles, MnOx/Ta4C3-SP, had TME-responsive T1-weighted MR imaging capabilities (see Figure 7A and B), while the photothermal conversion performance of Ta4C3 endowed MnOx/Ta4C3 NPs with photoacoustic imaging and photoconductive tumor ablation capabilities, in which tantalum was also used as a high-performance CT imaging contrast agent (see Figure 7C–E). This work provided a new strategy for both cancer diagnosis and photothermal therapy.

Figure 7.

1/T1 vs Mn concentration for MnOx/Ta4C3−SP composite nanosheets in buffer solution (A) at different GSH concentrations and (B) at different pH values after soaking for 3 hours. (C) Corresponding T1-weighted imaging of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice after intravenous administration of MnOx/Ta4C3−SP composite nanosheets for prolonged time intervals. (D) Time-dependent tumor-growth curves of four groups (control, NIR laser, MnOx/Ta4C3-SP, and MnOx/Ta4C3-SP + NIR laser groups) after receiving different disposes. (E) Digital images of tumors from each group at the end of the various treatments. Reproduced from Dai C, Chen Y, Jing XX, et al. Two-Dimensional Tantalum Carbide (MXenes) Composite Nanosheets for Multiple Imaging-Guided Photothermal Tumor Ablation. ACS Nano. 2017;11(12):12696–12712.131 Copyright © 2017 American Chemical Society.

Conclusion And Outlook

MRI is the fastest growing molecular imaging technology due to its non-invasive nature, high spatial resolution, non-ionizing radiation, soft tissue imaging, and so on. In order to improve the sensitivity of MRI, the study of CAs has attracted wide attention. Furthermore, due to their good biocompatibility, relatively high magnetization spin and rapid water proton exchange rate, MONs, rather than Gd-based, have been developed as a T1 CA, and have a huge clinical significance for the detection and diagnosis of cancer. This review summarizes recent advances in MONs-related multimodal imaging CAs and nanotheranostic agents, including MnO, Mn3O4, MnO2, and MnOx as MR CAs in MRI, bimodal or multimodal imaging, and imaging-guided therapy.

While the broad prospects of the MONs nanoplatform have been noted, they are still in the early lab stage. Similar to all nanostructures, the small size of nanomaterials gives them excellent physical and chemical properties, but their nanotoxicity is still unclear. For MONs, whether or not the crystal structure weakens the neurotoxicity of manganese itself requires further study. More importantly, the more functionality of a single nanoprobe is achieved at the expense of increasing complexity. The complex structures required to achieve versatility present enormous technical challenges in the construction and assembly of these nanoprobes, such as colloidal stability, controllability of experimental processes, reproducibility, and cost control. These challenges increase the difficulty of purifying the resulting nanoprobe, as well as the monodispersity of the final product, and lead to storage and shelf-life issues. These are all major challenges for the clinical transformation of MONs NPs.