Abstract

Objective

We aim to give an overview of the available evidence on brain structure and function in PHIV-infected patients (PHIV+) using long-term combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) and how differences change over time.

Methods

We conducted an electronic search using MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycINFO. We used the following selection criteria: cohort and cross-sectional studies that reported on brain imaging differences between PHIV+ of all ages who used cART for at least six months before neuroimaging and HIV-negative controls. Two reviewers independently selected studies, performed data extraction, and assessed quality of studies.

Results

After screening 1500 abstracts and 343 full-text articles, we identified 19 eligible articles. All included studies had a cross-sectional design and used MRI with different modalities: structural MRI (n = 7), diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) (n = 6), magnetic resonance spectroscopy (n = 5), arterial spin labeling (n = 1), and resting-state functional neuroimaging (n = 1). Studies showed considerable methodological limitations and heterogeneity, preventing us to perform meta-analyses. DTI data on white matter microstructure suggested poorer directional diffusion in cART-treated PHIV+ compared with controls. Other modalities were inconclusive.

Conclusion

Evidence may suggest brain structure and function differences in the population of PHIV+ on long-term cART compared with the HIV-negative population. Because of a small study population, and considerable heterogeneity and methodological limitations, the extent of brain structure and function differences on neuroimaging between groups remains unknown.

Although prevention of mother-to-child transmission in pregnant women infected with HIV has caused a great reduction in perinatal HIV infections, in 2016, still a total of 2.1 million children lived with HIV.1 The total population of perinatally HIV-infected patients (PHIV+) is likely to be larger because of survival of PHIV-infected children into adulthood.

Because of its neurotropic properties, HIV poses a major threat to normal brain development in infected children. Soon after birth, HIV migrates and subsequently resides in the central nervous system (CNS).2 Despite the profound effect of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) on HIV-related CNS pathology, persistent CNS related pathology in cART-treated PHIV+ is increasingly recognized.3 Different outcome measurements have been studied to reflect various CNS functions in this group, such as developmental milestone attainment,4 cognitive outcomes,5 and brain structures and function, as evaluated by MRI.6–8 All these reveal differences between HIV-infected children and healthy controls.

Imaging techniques have been increasingly used to investigate brain structure and function. Up to date, two systematic reviews have been published, giving an overview on the outcomes of brain imaging studies in PHIV+ children.9,10 However, because studies included untreated patients, little is known about brain imaging findings in the population of long-term cART-treated PHIV+.

After the introduction of cART, the prognosis of PHIV+ has improved, and infected children now survive into adulthood. Knowledge on CNS pathology in this population is crucial to understand their health status and to address further needs. We conducted a systematic review to aggregate scientific research on CNS pathology using neuroimaging in the population of long-term cART-treated PHIV+. This enables easy access for researchers to existing evidence and identifies directions for future research. We addressed the following questions: Is brain structure and function, measured by brain imaging, different in long-term cART-treated PHIV+ compared with healthy controls? And if so, how do these differences change over time?

Methods

We included cohort and cross-sectional studies that reported brain imaging differences between patients of all ages with PHIV infection, treated with cART for at least six months before imaging, and HIV-negative controls (HIV-exposed uninfected [HEU] or HIV-unexposed uninfected [HUU]). We assumed HIV infection to be perinatal in all pediatric patients, except when horizontal transmission was mentioned explicitly, and in adult patients when vertical transmission was mentioned in the majority of the study group. We defined cART as multiple antiretroviral agents from at least two different drug classes. We excluded studies based on the following criteria: case reports, case series, and nonoriginal studies, nonperinatal HIV infection in the majority of the study group, cART less than six months in the majority of patients at the time of neuroimaging, no information on the duration of cART, or when the authors mentioned poor therapy adherence in the majority of the study group. We excluded studies published before 1996, because of the nonavailability of cART, and studies with no full-text article available.

Search strategy

We searched the following databases: MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycINFO (tables e1–e3, links.lww.com/CPJ/A85). In addition, we searched references of relevant articles. We included artilces in all languages. The last search was conducted on April 17, 2018. We imported all records into the systematic review web application Rayyan11 and removed the duplicates. Two reviewers (M.V.d.H. and A.M.t.H.) independently screened titles and abstracts for eligibility and performed full-text selection. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion, and an arbitrator (D.P.) was available for consultation in case of persistent disagreement.

Data extraction and data analysis

Two reviewers (M.V.d.H. and A.M.t.H.) independently extracted the following data using a structured data extraction form: administrative data (authors, year of publication, country of research, study design, study period, and description of the population of cases and controls), general characteristics of study participants (age, sex, prematurity, small for gestational age, maternal substance abuse, socioeconomic status, nutrition status, and ethnicity), HIV-related characteristics (age at HIV diagnosis, plasma viral load [VL] at intervention(s), CD4% nadir, HIV VL zenith, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stage), therapy-related characteristics (age at start of antiretroviral therapy [ART], mono or dual ART in history and type of drugs, number of participants on cART, age at start of cART, duration of cART at intervention(s), and cART regimen class), details of imaging (indication for neuroimaging, age, strength of magnetic field [Tesla], general anesthesia used, and volume of interest), and outcome data (adjusted p values and, if available, effect sizes). We used data of eligible PHIV+. In case the authors did not report eligible patients separately, we used data of the whole study group (including a minority of noneligible patients).

Risk of bias assessment in included studies

Two reviewers (M.V.d.H. and A.M.t.H.) independently assessed the quality of individual studies using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality checklist for cross-sectional/prevalence studies12 and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cohort studies.13 Discrepancies were resolved by discussion, and an arbitrator (D.P.) was available for consultation in case of persistent disagreement.

Data availability

Any data not published within the article are available in a public repository and include digital object identifiers.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

We registered the review protocol in the PROSPERO database (CRD42017074477).14 We reported this systematic review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (table e-4, links.lww.com/CPJ/A85).15

Results

Selection procedure

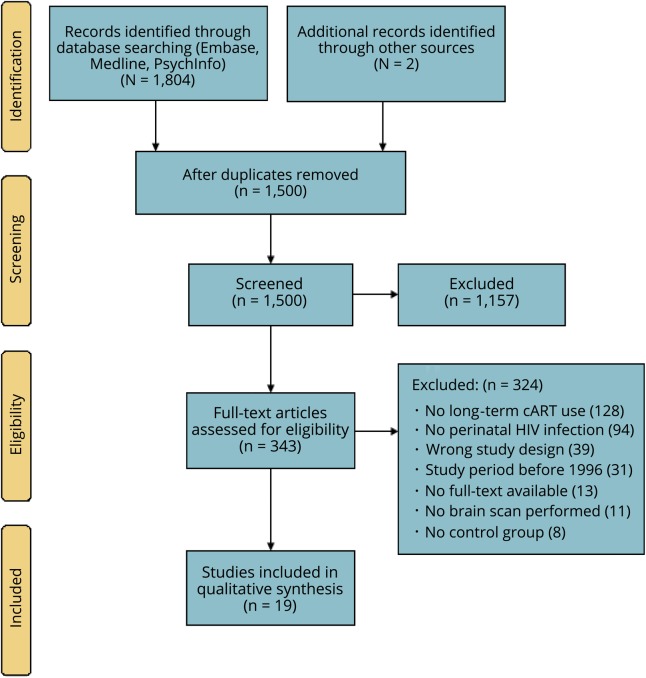

The search yielded 1500 titles and abstracts, of which 343 were selected for full-text screening (figure). Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we included 19 studies.

Figure. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram.

cART = combination antiretroviral therapy.

Study characteristics

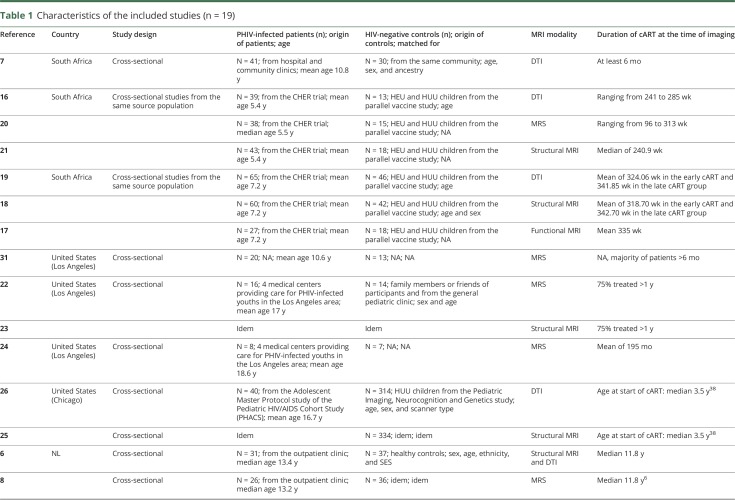

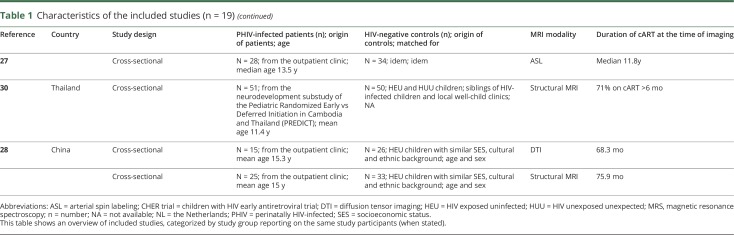

All studies had a cross-sectional design; no cohort data were available. Six studies sampled patients from the same source population (children who participated in the Children with HIV Early Antiretroviral Therapy [CHER] trial); these studies did not perform longitudinal analyses.16–21 Studies were mainly conducted in South Africa (n = 7)7,16–21 and the United States (n = 6),22–26 followed by the Netherlands (n = 3),6,8,27 China (n = 2),28,29 and Thailand (n = 1)30 (table 1). In the 19 included studies, we identified 10 study populations; many studies examined the same study participants concurrently but reported different outcome measurements per article. The number of PHIV+ per study ranged from 8 to 65, with a median of 31. Although it was not possible to track down exactly how many patients were reported in more than one paper, the total population of all studies comprised approximately 340 unique patients. The age of the study participants ranged from 5 to 25 years. Fourteen studies reported in detail on the duration of cART, with the shortest duration being 96 weeks20 and the maximum duration being the median of 11.8 years.6 The remaining studies reported a minimum duration of cART of at least six months7,30,31 or one year22,23 in the majority of patients. Studies predominantly included HUU patients as the control group and, to a lesser extent, HEU patients (in four studies). In nine studies, groups were matched for sex and/or age,16,18,19,22,23,25,26,28,29 and in four studies also for ethnicity and/or socioeconomic status.6,8,27,32 All studies used MRI for neuroimaging. Seven studies used structural MRI scanning,6,18,21,23,25,28,30 six studies used diffusion tensor imaging (DTI),6,7,16,19,26,29 and five magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS).8,20,22–24 Two studies used different MRI modalities: arterial spin labeling (ASL) (n = 1)27 and resting-state functional MRI (RS-fMRI) (n = 1).17

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies (n = 19)

Quality of studies

In the majority of studies (n = 16), the authors did not report clearly on the selection procedure of study participants (table e-5, links.lww.com/CPJ/A85). Most studies (n = 18) did not report blinding of the evaluators to subjective components. The authors described confounding factors in 16 studies, but across studies, the authors used different variables as possible confounders per outcome. In all studies (n = 19), the authors did not report completeness of data collection and how they handled missing data.

Neuroimaging outcomes

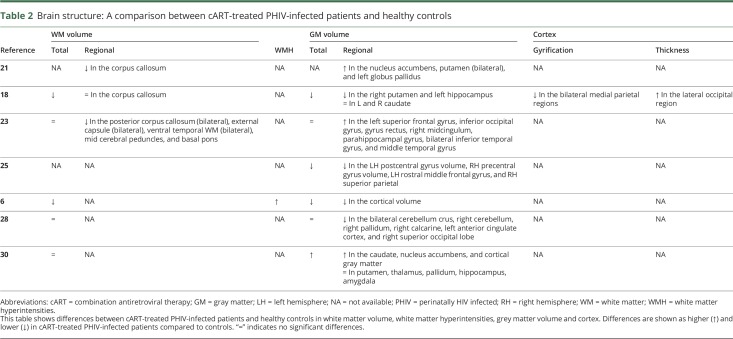

Structural outcomes

Seven studies performed structural MRI scanning in PHIV+ on long-term cART and healthy controls.6,18,21,23,25,28,30 Table 2 shows differences between cART-treated PHIV+ and healthy controls in white matter (WM) volume, white matter hyperintensities (WMH), gray matter (GM) volume, and cortex. Three of five studies reporting on total WM volume concluded that it was comparable between groups,23,28,30 whereas two studies found lower volumes6,18 in PHIV+ compared with healthy controls. Three studies described regional volume differences: two studies found lower regional volumes,21,23 one study reported comparable volumes.18 One study, in which outcome assessors were blinded, reported structural WM abnormalities and found a significantly higher number of WMH in PHIV+ children compared with healthy controls (59% vs 18%).6 Three of six studies reporting on total GM volume found a lower volume in PHIV+ compared with healthy controls. Studies that reported regional GM volumes studied different areas and found lower,6,18,25,28 comparable,23,28,30 or higher21,23,30 regional GM volume in cART-treated PHIV+ compared with healthy controls.

Table 2.

Brain structure: A comparison between cART-treated PHIV-infected patients and healthy controls

WM microstructure

DTI metrics include fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), radial diffusivity (RD), and axial diffusivity (AD) and depict the microstructural properties of WM.33 Lower FA and higher MD in patients compared with controls are representative of more isotropic and increased diffusion, indicating damaged neuronal microstructure.33 AD and RD can be indirectly related to axonal degeneration and demyelination, respectively. Six of the included studies investigated WM microstructure in cART-treated PHIV+ compared with healthy controls,6,7,16,19,26,29 the results of which are shown in table 3. All these studied whole brain and/or regional FA, and all found lower FA levels in cART-treated PHIV+ compared with controls, suggesting microstructural impairment. Two studies measured whole brain MD and found higher values in cART-treated PHIV+ compared with controls, representing higher diffusion.6,26 Studies that evaluated regional MD values found higher and lower MD levels in different regions.7,16,19,29 Studies that evaluated RD levels found higher levels in cART-treated PHIV+, possibly suggesting relative demyelination.6,7,26 Three studies measured whole brain or regional AD values and found conflicting results: comparable, higher, and lower AD values in cART-treated PHIV+ compared with controls.6,7,26

Table 3.

White matter integrity: A comparison between cART-treated PHIV-infected patients and healthy controls

Brain neurometabolites

We included five studies that performed MRS in PHIV+.8,20,22–24 Table 4 shows differences between cART-treated PHIV+ and healthy controls in brain metabolites in different regions, categorized by neuronal function metabolites and glial marker metabolites. In three studies N-acetylaspartate (NAA), glutamate, and gamma-aminobutyric acid levels were comparable between cART-treated PHIV+ and healthy controls.8,22,23 Levels of glial activation markers, such as myo-inositol (mI) and choline (Cho), were comparable between groups in the majority of studies. Three studies found higher levels of Cho and mI in PHIV+ compared with healthy controls in different regions, indicating glial cell proliferation.8,20,31

Table 4.

Brain metabolites: A comparison between cART-treated PHIV-infected patients and healthy controls

Other outcome measurements

Two studies reported other MRI outcome measurements: cerebral blood flow (CBF), using ASL,27 and resting-state functional connectivity, using RS-fMRI.17 The latter provides information on functional connectivity within brain networks. CBF was higher in WM and in parts of the basal ganglia (nucleus caudate, putamen, nucleus accumbens, and thalamus) in cART-treated PHIV+ compared with healthy controls.27 Studying functional connectivity, the authors did not find differences of functional connectivity within networks, but found major differences in functional connectivity between networks between cART-treated PHIV+ and healthy controls.17

Discussion

In this systematic review, we summarize the available evidence on differences in brain structure and function between cART-treated PHIV+ and healthy controls. Our findings suggest that brain structure and function differ in long-term cART-treated PHIV+ compared with healthy controls. We found no study reports on whether and how these differences change over time.

Studies used different MRI modalities, with structural MRI scanning being the most commonly performed. Data from these studies show conflicting results, with total GM and WM volume being lower or comparable between PHIV+ and healthy controls. DTI data on WM microstructure suggest poorer directional diffusion in cART-treated PHIV+, indicating damaged neuronal microstructure. For MRS studies, the number of studies is small, and results are inconclusive. In long-term cART-treated PHIV+, we do not see differences with healthy controls with regard to NAA, which used to be a marker for HIV encephalopathy.34–36 During the past years, more innovative MRI techniques are being used to assess brain structure and function, such as ASL and RS-fMRI. However, the number of these studies is small, limiting the insights into brain differences of cART-treated PHIV+.

Longitudinal data were lacking, hampering conclusions on how differences in brain structure and function in cART-treated PHIV+ change over time. Although South African studies repeatedly sampled study participants from the same CHER cohort with the vast majority of the samples being the same study participants, these studies did not perform longitudinal analyses.17–21,37

Two previous reviews on this topic, published in 2014 and 2016, summarized existing evidence on neuroimaging outcomes in predominantly untreated PHIV+ children and adolescents.9,10 These reviews found differences between PHIV+ and controls; however, they did not the include risk of bias assessment to evaluate the methodological quality of the included studies. Moreover, our systematic review was limited to PHIV+ on long-term cART, and as such, we could not include any of the previously included articles.

This systematic review revealed that only a very small number of cART-treated PHIV+ have been investigated by MRI neuroimaging. The majority of the studies reported on the same study participants, limiting the number of unique patients from whom data are available. Taking this into account, generalizing outcomes derived from these studies to the whole population of long-term cART-treated PHIV+ is a subject of concern.

Major concerns exist about the risk of bias in the included studies because of the lack of information regarding important methodological aspects, such as selection of study participants, missing data, and blinding of evaluators, thereby limiting us to draw valid conclusions. The majority of studies did not prespecify MRI regions of interest and incorporated a large number of statistical tests to compare brain regions in PHIV+ and controls. Although the majority of studies corrected for multiple testing, type I errors cannot be ruled out.6,8,23,25,27,30,31

We found a high degree of heterogeneity across the studies. Studies measured brain structure and function in a variety of ways and of different (often very detailed) localizations, without clear previously proposed hypotheses. Studies varied widely regarding the age of participants. Although all individual studies in this systematic review included an HIV-uninfected control group to whom outcomes of HIV-positive children were compared to, because of the limited number of studies available, it was impossible to explore age subgroups. We also noticed heterogeneity in the origin of control groups. To draw valid conclusions, it is essential to evaluate a sample of HIV-uninfected controls from the same source population of PHIV+. Taken this all together, our analysis could merely be descriptive, and we were unable to perform a meta-analysis. Finally, although we find brain structure and function differences between cART-treated PHIV+ and controls in this systematic review, we cannot draw conclusions on the causality of these differences. Because of the limited number of studies and high degree of heterogeneity, we were unable to explore associations, for example, between (the duration of) cART and neuroimaging outcomes. Adding longitudinal evidence studying brain structure and function in cART-treated PHIV+ children will increase insight in possible mechanisms driving these brain alterations.

For future research, we strongly suggest undertaking longitudinal neuroimaging studies in PHIV-infected children and appropriate matched controls to study brain structure and function based on clear hypotheses about presumed changes in prespecified regions.

This systematic review suggests differences in brain structure and function between long-term cART-treated PHIV+ and healthy controls. However, because of large heterogeneity between studies, small sample sizes, and considerable methodological limitations, the extent of these differences remains unknown.

Appendix. Authors

Footnotes

Editorial 371

Study funding

This work was supported by the AIDSfonds (grant number 2015009).

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.WHO. Prevent HIV, Test and Treat All: WHO Support for Country Impact. Progress Report 2016. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valcour V, Chalermchai T, Sailasuta N, et al. Central nervous system viral invasion and inflammation during acute HIV infection. J Infect Dis 2012;206:275–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blokhuis C, Kootstra N, Caan M, Pajkrt D. Neurodevelopmental delay in pediatric HIV/AIDS: current perspectives. Dovepress 2016;7:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benki-Nugent S, Wamalwa D, Langat A, et al. Comparison of developmental milestone attainment in early treated HIV-infected infants versus HIV-unexposed infants: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pediatrics 2017;17:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phillips N, Amos T, Kuo C, et al. HIV-associated cognitive impairment in perinatally infected children: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2016;138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen S, Caan MW, Mutsaerts HJ, et al. Cerebral injury in perinatally HIV-infected children compared to matched healthy controls. Neurology 2016;86:19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoare J, Fouche JP, Phillips N, et al. White matter micro-structural changes in ART-naive and ART-treated children and adolescents infected with HIV in South Africa. AIDS 2015;29:1793–1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Dalen YW, Blokhuis C, Cohen S, et al. Neurometabolite alterations associated with cognitive performance in perinatally HIV-infected children. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Musielak KA. An updated systematic review of neuroimaging studies of children and adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV. J Pediatr Neuropsychol 2016;2:34–49. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoare J, Ransford GL, Phillips N, Amos T, Donald K, Stein DJ. Systematic review of neuroimaging studies in vertically transmitted HIV positive children and adolescents. Metab Brain Dis 2014;29:221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016. 5:210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeng X, Zhang Y, Kwong JS, et al. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. J Evid Based Med 2015;8:2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2013. Available at: ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed May 1, 2018.

- 14.PROSPERO. Available at: crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/. Accessed September 27, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting Items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ackermann C, Andronikou S, Saleh MG, et al. Early antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected children is associated with diffuse white matter structural abnormality and corpus callosum sparing. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2016;37:2363–2369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toich JT, Taylor PA, Holmes MJ, et al. Functional connectivity alterations between networks and associations with infant immune health within networks in HIV infected children on early treatment: a study at 7 years. Front Hum Neurosci 2018;11:635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nwosu EC, Robertson FC, Holmes MJ, et al. Altered brain morphometry in 7-year old HIV-infected children on early ART. Metab Brain Dis 2018;33:523–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jankiewicz M, Holmes MJ, Taylor PA, et al. White matter abnormalities in children with HIV infection and exposure. Front Neuroanat 2017;11:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mbugua KK, Holmes MJ, Cotton MF, et al. HIV-associated CD4+/CD8+ depletion in infancy is associated with neurometabolic reductions in the basal ganglia at age 5 years despite early antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2016;30:1353–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Randall SR, Warton CMR, Holmes MJ, et al. Larger subcortical gray matter structures and smaller corpora callosa at age 5 Years in HIV infected children on early ART. Front Neuroanat 2017;11:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagarajan R, Sarma MK, Thomas MA, et al. Neuropsychological function and cerebral metabolites in HIV-infected youth. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2012;7:981–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarma MK, Nagarajan R, Keller MA, et al. Regional brain gray and white matter changes in perinatally HIV-infected adolescents. Neuroimage Clin 2014;4:29–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iqbal Z, Wilson NE, Keller MA, et al. Pilot assessment of brain metabolism in perinatally HIV-infected youths using accelerated 5D echo planar J-resolved spectroscopic imaging. PLoS One 2016;11:e0162810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis-de los Angeles C, Williams PL, Huo Y, et al. Lower total and regional grey matter brain volumes in youth with perinatally-acquired HIV infection: associations with HIV disease severity, substance use, and cognition. Brain Behav Immun 2017;62:100–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uban KA, Herting MM, Williams PL, et al. White matter microstructure among youth with perinatally acquired HIV is associated with disease severity. AIDS 2015;29:1035–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blokhuis C, Mutsaerts HJ, Cohen S, et al. Higher subcortical and white matter cerebral blood flow in perinatally HIV-infected children. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e5891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li J, Gao L, Wen Z, et al. Structural covariance of gray matter volume in HIV vertically infected adolescents. Scientific Rep 2018;8:1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li J, Wu G, Wen Z, et al. White matter development is potentially influenced in adolescents with vertically transmitted HIV infections: a tract-based spatial statistics study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015;36:2163–2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paul R, Prasitsuebsai W, Jahanashad N, et al. Structural neuroimaging and neuropsychologic signatures of vertically acquired HIV. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2018;37:662–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keller MA, Venkatraman TN, Thomas A, et al. Altered neurometabolite development in HIV-infected children: correlation with neuropsychological tests. Neurology 2004;62:1810–1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoare J, Fouche JP, Phillips N, et al. Clinical associations of white matter damage in cART-treated HIV-positive children in South Africa. J Neurovirol 2015;21:120–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feldman HM, Yeatman JD, Lee ES, Barde LH, Gaman-Bean S. Diffusion tensor imaging: a review for pediatric researchers and clinicians. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2010;31:346–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pavlakis SG, Lu D, Frank Y, et al. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy in childhood AIDS encephalopathy. Pediatr Neurol 1995;12:277–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pavlakis SG, Lu D, Frank Y, et al. Brain lactate and N-acetylaspartate in pediatric AIDS encephalopathy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1998;19:383–385. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salvan AM, Lamoureux S, Michel G, Confort-Gouny S, Cozzone PJ, Vion-Dury J. Localized proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the brain in children infected with human immunodeficiency virus with and without encephalopathy. Pediatr Res 1998;44:755–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ackermann C, Andronikou S, Laughton B, et al. White matter signal abnormalities in children with suspected HIV-related neurologic disease on early combination antiretroviral therapy. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2014;33:e207–e212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lewis-de los Angeles CP, Alpert KI, Williams PL, et al. Deformed subcortical structures are related to past HIV disease severity in youth with perinatally acquired HIV infection. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc 2016;5:S6–S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Any data not published within the article are available in a public repository and include digital object identifiers.