Abstract

Background

College students are at increased risk for sleep disorders, including insomnia disorder and obtaining less than 6.5 hr of sleep per night by choice, or behaviorally induced insufficient sleep syndrome (BIISS). These disorders can have deleterious daytime consequences, including depression. This study aims to establish the prevalence of insomnia and BIISS disorders and examine associations of insomnia and BIISS with other sleep characteristics and depression.

Methods

A subset of data from Spit for Science, a college risk behaviors and health study (n = 989) was used. Insomnia and BIISS were defined as mutually exclusive disorders, based on diagnostic criteria.

Results

A majority (68%) of students were categorized as normal sleepers, followed by insomnia (22%), and BIISS (10%). Sleep duration was comparable between BIISS and insomnia, while daytime sleepiness was significantly higher in BIISS, and sleep latency was longer in insomnia (m = 44 vs. m = 13 min). Insomnia was associated with the highest depression symptoms, followed by BIISS, and normal sleep, controlling for demographics. Insomnia was associated with twice the risk of moderate or higher depression compared to normal sleep (CI: 1.60, 2.70, p < .001).

Conclusion

These findings highlight the sleep difficulties endemic to college populations. Further, this study provides the first prevalence estimation of BIISS in college students and the first comparison of insomnia and BIISS on sleep characteristics and depressive symptoms. This study underscores the importance of targeted screening and intervention to improve both sleep and depression in this vulnerable population.

College students are at increased risk for sleep problems and depressed mood, which are both associated with considerable negative consequences. Insomnia disorder (“insomnia”) and behaviorally induced insufficient sleep syndrome (BIISS) represent distinct, mutually exclusive sleep disturbances (World Health Organization, 1992). Insomnia disorder is defined as difficulty with sleep onset, duration, maintenance, or quality despite adequate opportunity (World Health Organization, 1992). BIISS is characterized by volitional short sleep duration accompanied by daytime sleepiness (Schutte-Rodin, Broch, Buysse, Dorsey, & Sateia, 2008; World Health Organization, 1992). The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends 6.5 hr or less as a sleep duration cutoff for insomnia, and previous studies have used less than 7 hr as a cutoff for BIISS (Schutte-Rodin et al., 2008; Lee, Cho, Cho, & Kim, 2012; Pallensen et al., 2011). Notably, BIISS differs from insomnia in that sleep restriction is voluntary, quality is normal, and there are no difficulties with onset or maintenance.

The convergence of biological and environmental changes associated with adolescence and emerging adulthood contribute to college students’ increased vulnerability for sleep difficulties (Baglioni, Battagliese, & Feige, 2011). College students have recently undergone puberty-linked biological changes, including a preference for delayed sleep and wake times that make it difficult to obtain adequate sleep duration (Carskadon, Acebo, & Seifer, 2001; Crowley, Acebo, & Carskadon, 2007). Moreover, college introduces unique environmental risk factors including new peer groups, more rigorous academic responsibilities, louder sleep environments, homesickness, and increased substance use (Taylor, Bramoweth, Grieser, Tatum, & Roane, 2013).

These environmental and biological factors may contribute to insomnia or BIISS, both of which are assumed to be prevalent in college. Though insomnia is likely common in college, prevalence estimates vary considerably, from 14% to 47%, depending on diagnostic criteria (Gress-Smith, Roubinov, Andreotti, Compas, & Luecken, 2015). One review paper examined the wide range of findings and concluded that insomnia symptoms are estimated to be 30%, while clinical diagnoses of insomnia disorder are estimated at 5–10% of the population (Mai & Buysse, 2008). BIISS has been demonstrated to affect 10–19% of high school students (Lee et al., 2012; Pallesen et al., 2011). Although no studies have established BIISS’ prevalence in college students, BIISS is assumed to be widespread because insufficient sleep and daytime sleepiness (cardinal symptoms of BIISS) are prevalent in college (Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2005). Insufficient sleep is common in college students: ~70% of students obtained less than 8 hr and 25% obtained under 6.5 hr of sleep per night (Lund, Reider, Whiting, & Prichard, 2010; Steptoe, Peacey, & Wardle, 2006). Further, ~35–60% of college students report daytime sleepiness, compared to ~3–18% of the general population (Oginska & Pokorski, 2006; Whittier et al., 2014).

Substantial research has demonstrated that insomnia and insufficient sleep impair the physical health, safety, academic performance, and mental health in adolescence and emerging adulthood (e.g., Gaultney, 2010; Shochat, Cohen-Zion, & Tzischinsky, 2014). In particular, the relationship between sleep difficulties and mental health in college students has garnered increasing attention, as insufficient sleep and mental health have both been flagged as public health priorities for young adults (Centers for Disease Control, 2016; Mombray et al., 2006). Specifically, insomnia and BIISS are both linked with increased symptoms of depression (e.g., Gress-Smith et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2012), another problem endemic to college students. College is a critical time to screen for and understand depression, given that depression rates increase with puberty, 10% of college students are formally diagnosed with depression, and another 30% of college students report depressive symptoms (American College Health Association, 2006; Sarokhani et al., 2013). Further, depression when coupled with sleep difficulties can become chronic, with a negative influence across key domains.

The relationship between insomnia and depression is well established: Insomnia is a risk and maintaining factor for depression, with more severe and chronic symptoms of insomnia predicting more severe depression (e.g., Riemann & Voderholzer, 2003). Additionally, insomnia predicts suicidal ideation, attempts, and completion (Nadorff, Nazem, & Fiske, 2011). To date, only two studies have explored the relationship between BIISS and depression; both found that BIISS predicted depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation in high school students (Lee et al., 2012; Pallesen et al., 2011). More extensive research has consistently reported an association between insufficient sleep or daytime sleepiness (without specifying BIISS) and depression (e.g., Moore et al., 2009; Regestein et al., 2010). However, studies on insufficient sleep and depression often include participants with insomnia, which has made it difficult to determine if insomnia is driving the association between sleep and depressive symptoms, or if insufficient sleep—even in the absence of insomnia—is related to depression.

There are several key psychological, behavioral, and physiological pathways through which sleep may contribute to depressive symptoms. First, insufficient sleep is central to both insomnia and BIISS. Insufficient sleep may impact quality of life, interpersonal relationships, and occupational and academic functioning, which, in turn, might contribute to the onset or maintenance of depression. Further, sleep loss may cause neurobehavioral alterations that contribute to depression, through HPA dysfunction and increased cortisol (McCall & Black, 2013). Symptoms specific to insomnia may also uniquely contribute to depression, such as increased rumination while lying awake at night or increased hopelessness and helplessness from being unable to control sleep (Taylor et al., 2011). Additionally, daytime sleepiness associated with BIISS may limit social engagement or academic functioning, which could contribute to depression. However, no research has compared BIISS to insomnia on depression, so conclusions on which sleep disorder is associated with greater depression—and mechanisms of action—are limited.

To date, no studies have evaluated the prevalence of BIISS in college students, despite the fact that late adolescence is a high-risk period for insufficient sleep. Further, no studies have separated out insomnia and BIISS within the same sample to compare prevalence rates and differences in sleep presentation. Moreover, though there has been substantial literature establishing a strong link between insufficient sleep and depression, most studies did not exclude participants with insomnia, making it difficult to determine if insufficient sleep, in the absence of insomnia, predicts depression. A comparison of BIISS and insomnia is needed to understand their relative risk and potential mechanisms from sleep disturbances to depression. Finally, it is important to conduct this comparison in a college sample, given the increased risk for both sleep problems and for mental health problems, both of which can become chronic issues with cascading effects on other domains.

Broadly, the present study explores the relationship between insomnia or BIISS and depressive symptoms in college students. To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare prevalence and sleep characteristics of insomnia and BIISS, as well as the first to examine their respective ties to depression. Study aims are as follows: (a) establish relative prevalence rates for insomnia and BIISS, which we hypothesize to be commensurate with previous college student studies on insomnia and higher than adult studies on BIISS; (b) compare rates of depressive symptoms across college students with insomnia, BIISS, and normal sleep, hypothesizing that college students with insomnia will have the highest levels of depressive symptoms, followed by those with BIISS, and finally individuals with normal sleep; and (c) evaluate insomnia and BIISS’ relative risk for experiencing moderate or higher depressive symptoms, hypothesizing that both insomnia and BIISS would be associated with greater risk of moderate or higher depressive symptoms compared to normal sleep.

Method

Data set

This study used data from the 2011 third-year cohort of Spit for Science, a longitudinal study of college undergraduates examining substance use, physical and mental health, and genetic influences (Dick et al., 2014). This paper used the 2011 third-year cohort, the only data set with sleep questions available at the time of analysis.

Study procedures

The study took place at a public, urban campus in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. For this study’s cohort, initial recruitment began in the fall of 2011. Eligible first-year students were recruited via e-mail and flyers. After informed consent, participants completed a 15–30 min survey and were compensated $10. Study data were collected and managed electronically using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap; Harris et al., 2009).

Participants were invited to participate in follow-up surveys annually. This wave of data was administered in Spring 2014 to college third-year strudents. Participants completed the 15–30 min survey online and were compensated $10. The institutional review board approved study procedures.

Participants

The sample includes participants from the 2011 cohort of third-year college students (n = 989). Eligibility criteria included (a) current status as a third-year student at the university, and (b) survey completion as first-year students.

Measures

Sleep

Sleep was assessed using four items from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, 1989) initially selected for the Spit for Science study. Because of the comprehensive nature of the survey, including numerous behavioral and psychological measures, to reduce subject burden, four items deemed to be the most essential to making inferences about sleep disorders were selected. The PSQI measures sleep over the past month without specifying weekend versus weekday sleep. Sleep duration and sleep onset latency were assessed via free response. Sleep quality response options ranged from 1 = very bad to 4 = very good. Daytime sleepiness (“How often have you had trouble staying awake while driving, eating meals, or engaging in social activity”) ranged from 1 = not during the past month to 4 = three or more times/week). Cronbach’s α for the full PSQI is .83 and for the four sleep items in this study was 0.73, which is considered acceptable (Cortina, 1993).

Using this information, mutually exclusive, categorical variables were created for insomnia, BIISS, and normal sleep, based on diagnostic criteria from the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10), as well as a designated cutoff score for insufficient sleep (World Health Organization, 1992). We defined insufficient sleep conservatively, using 6.5 hr or less as our cutoff, to conform with the American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommendations and previous research, as well as to minimize overdiagnosis of BIISS or insomnia in a population where insufficient sleep is widespread (Schutte-Rodin et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2012; Pallensen, 2011). However, given that under 7 hr can be considered insufficient in young adults, we also conducted sensitivity analyses and report prevalence rates with 7 hr as a cutoff for comparison (National Sleep Foundation, 2015).

Insomnia and BIISS represent mutually exclusive disorders, defined per ICD-10 guidelines and research norms (World Health Organization, 1992; Table 1). Insomnia was defined as insufficient sleep (≤ 6.5 hr) and either poor sleep quality (fairly bad to very bad) or long sleep latency (≥ 30 min). Daytime sleepiness could be present but was not required for insomnia diagnosis. BIISS was defined as insufficient sleep (≤ 6.5 hr) with good sleep quality (fairly good to very good) and normal sleep latency (< 30 min), to demonstrate that sleep restriction was voluntary (vs. attributable to long latency or poor quality). As daytime sleepiness is a key criterion of BIISS, BIISS required endorsement of daytime sleepiness at least once per week. “Normal sleep” was defined as not meeting criteria for either insomnia or BIISS.

Table 1.

Diagnostic characteristics of insomnia and BIISS.

| Insomnia disorder | BIISS | |

|---|---|---|

| Duration | ≤ 6.5 hr | ≤ 6.5 hr |

| Sleep quality | Either poor sleep quality | Good sleep quality |

| Long sleep latency | Or long sleep latency (≥ 30 min) | Normal sleep latency (< 30 min) |

| Daytime sleepiness | Can have daytime sleepiness but not needed for diagnosis | Increased daytime sleepiness |

Demographics

Participants were asked to report gender and race or ethnicity. Gender was coded as 0 = male, 1 = female. Race was dummy coded, using Caucasian as the reference group.

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the available eight items from the depression subscale of the Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90), a self-report measure of psychological symptoms over the past 90 days (Derogatis & Cleary, 1977). As with the sleep items, these items were selected to balance brevity with reliability. Items assessed feeling blue, hopelessness about the future, loss of interest in activities or sex, low energy, self-blame, sense of worthlessness, and feeling everything is effortful. Items assessed depression symptoms over the past month from not at all to extremely. Scores were treated continuously for t-tests and ANCOVA. Scores were dichotomized for risk ratio tests, into “less than moderate depressive symptoms” on average (< 24 score) or “moderate or greater depressive symptoms” (≥ 24), which is consistent with a previous study using a partial version of this scale that suggested that moderate or greater symptoms may be a potential indicator for clinically significant depression (Clark, 2015). Chronbach’s α was .906 for this scale, indicative of excellent reliability (Cortina, 1993).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used for sleep characteristics and prevalence rates of insomnia, BIISS, and normal sleep. Three independent-samples t-tests were used to confirm that insomnia and BIISS categories differed on two of the key differential diagnostic criteria (i.e., daytime sleepiness and sleep-onset latency) and to examine whether they differed on the overlapping criteria of having ≤ 6.5 hr of sleep. Correlation analyses evaluated correlations among sleep duration, daytime sleepiness, sleep quality, and sleep-onset latency. A one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted, controlling for ethnicity and gender, to examine group differences (insomnia vs. BIISS) in terms of depressive symptoms. Planned contrasts compared (a) insomnia to BIISS, (b) BIISS to normal sleep, and (c) insomnia to normal sleep on depressive symptoms. Two relative risk and chi-square analyses were conducted to examine the relative risk of experiencing moderate or higher depression, comparing insomnia versus normal sleep, and BIISS versus normal sleep. Finally, sensitivity analyses were conducted to determine if using under 7 hr as the cutoff definition for insufficient sleep for BIISS and insomnia influenced primary sleep and depression results. SPSS v.22.0 was used for all analyses (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

Sleep characteristics and prevalence of insomnia and BIISS

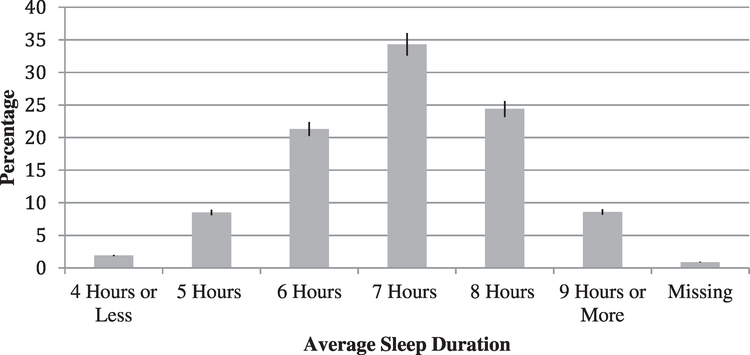

Demographics and descriptive characteristics for sleep for the overall sample are presented in Table 2. Selected sleep characteristics by insomnia, BIISS, and normal sleep are presented in Table 3. Average sleep duration is presented in Figure 1. Prevalence rates included 22.1% insomnia, 9.9% BIISS, and 67.2% normal sleep.

Table 2.

Demographics and sleep.

| Variable | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 647 | 65.60% |

| Male | 332 | 33.60% |

| I choose not to answer | 6 | 0.60% |

| Race | ||

| White/Caucasian | 466 | 47.10% |

| Black/African American | 217 | 21.90% |

| Asian | 184 | 18.60% |

| Hispanic/Latino | 42 | 4.20% |

| More than one race | 52 | 5.30% |

| American Indian/Native Alaskan | 4 | 0.60% |

| Unknown | 3 | 0.30% |

| I choose not to answer | 11 | 1.10% |

| Age | ||

| 19 | 6 | 0.60% |

| 20 | 595 | 60.16% |

| 21 | 372 | 37.61% |

| 22 or older | 16 | 1.60% |

| Sleep | ||

| Daytime sleepiness | ||

| Three or more times a week | 50 | 5.10% |

| Once or twice a week | 167 | 16.90% |

| Less than once a week | 315 | 31.90% |

| Not during the past month | 442 | 44.80% |

| Sleep latency | ||

| 0–15 min | 417 | 44.84% |

| 16–30 min | 324 | 34.84% |

| 31–45 min | 61 | 6.56% |

| 46–60 min | 92 | 9.89% |

| More than 60 min | 36 | 3.87% |

| Sleep quality | ||

| Very bad | 12 | 1.20% |

| Fairly bad | 153 | 15.50% |

| Fairly good | 695 | 70.40% |

| Very good | 122 | 12.40% |

Table 3.

Sleep characteristics by group.

| Insomnia (n = 218) | BIISS (n = 98) | Normal (n = 663) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep | |||

| Duration | 5.67 hr (SD = 45 min) | 5.80 hr (SD = 36 min) | 7.43 hr (SD = 56 min) |

| Quality | “Fairly bad quality” 2.45 (SD = .62) | “Fairly good quality” 3.16 (SD = .37) | “Fairly good quality” 3.07 (SD = .49) |

| Latency | 44 min (SD = 34.26) | 13 min (SD = 0.1) | 23 min (SD = 19.43) |

| Daytime sleepiness | 2.06 (SD = .98) | 2.54 (SD = 7.1) | 1.64 (SD = .82) |

Note. Min = minutes, hr = hours.

Figure 1.

Average sleep duration by hour for all participants.

An independent-samples t-test (t[233.65] = −1.528, p = .128) did not show evidence of differences in sleep duration between the insomnia (m = 340.65, SD = 45.45) and BIISS (m = 347.92, SD = 35.85). An independent-samples t-test confirmed that insomnia (m = 2.1, SD = .98) was associated with significantly less daytime sleepiness than the BIISS (m = 2.54, SD = .71); t[311] = −4.96, p < .001, d = .514). Insomnia (m = 43.86, SD = 34.23) was associated with significantly longer sleep latency than BIISS (m = 13.28, SD = 10.14); t(275.43) = 11.83, p < .001, d = 1.21.

Depressive symptoms and sleep group

Participants reported an average depression symptom score of 17.74 (SD = 7.36), which corresponded with endorsing depression “a little bit.” Insomnia was associated with the highest depressive symptoms (m = 18.69, SD = 7.95), followed by BIISS (m = 17.04, SD = 6.1), and finally, normal sleep (m = 15.39, SD = 6.46). Further, 40.8% of participants endorsed depressive symptoms on average not at all, 28.7% a little bit, 17.4% moderately, 9.1% quite a bit, and 4.1% extremely. When depression was dichotomized for odds ratios, 69.4% endorsed less than moderate symptoms of depression, compared to 30.6% who endorsed moderate or greater depressive symptoms.

Correlation analyses demonstrated that all sleep variables were significantly associated with depression, including sleep-onset latency, r = .23, p < .01, daytime sleepiness r = .28, p < .01, sleep quality r = −.27, p < .01, and sleep duration r = −.12, p < .01. ANCOVA analyses, controlling for ethnicity and gender, demonstrated that sleep group (insomnia, BIISS, or normal sleep) predicted depressive symptoms, F(2,906) = 20.57, p < .001. Per planned contrasts, insomnia (m = 18.77, SD = .47) was associated with more depression than BIISS (m = 17.16, SD = .70), f(1, 170) = 3.80, p < .05. Further, insomnia was associated with more depressive symptoms than normal sleep (m = 15.36, f[1,1752] = 39.98, p < .01). Finally, BIISS was associated with more depressive symptoms than normal sleep, f(1,239.05) = 5.32, p = .02.

The relative risk of having moderate depressive symptoms or higher was 2.06 times (95% CI: 1.59–2.70; p < .05) greater for insomnia compared to normal sleep. The relative risk of having moderate depressive symptoms for BIISS compared to normal sleep was 1.4 times (95% CI: .92–2.1, p = .09) greater for BIISS than for normal sleep.

Sensitivity Analysis

Given the range of definitions for insufficient sleep and that under 7 hr can be considered insufficient in young adults, sensitivity analyses were conducted to determine if using under 7 hr as the cutoff definition for insufficient sleep for BIISS and insomnia influenced results. Prevalence rates were similar with a cutoff of less than 7 hr/night: 23.3% endorsed insomnia (compared to 22.1% with a 6.5 hr or less cutoff), 10.6% BIISS (compared to 9.9% BISS with 6.5 hr or less cutoff), and 65.2% normal sleep (compared to 67.2% normal sleep with 6.5 hr or less cutoff). Moreover, reanalysis of the primary aims using this cutoff resulted in an equivalent pattern of findings and yielded no appreciable between-group differences in depressive symptoms, as anticipated given the negligible differences in prevalence rates.

Discussion

The present study aimed to establish the prevalence of insomnia and BIISS in a college sample and to explore the relationships between BIISS or insomnia and depression. This study found that both BIISS and insomnia were prevalent, with approximately one third of students having one of the two disorders. Moreover, insomnia, BIISS, and normal sleep differentially related to depressive symptoms: insomnia predicted the most depressive symptoms, followed by BIISS and normal sleep.

Insomnia disorder and BIISS

The prevalence of insomnia disorder was estimated at 22.1%, which is consistent with the existing literature on college students, which indicates that 12–25% of college students experience insomnia (Gress-Smith et al., 2015; Schutte-Rodin et al., 2008). The prevalence of BIISS was estimated at 9.9%. As this is the first study to evaluate the prevalence of BIISS in college students, direct comparisons are limited. However, previous works had estimated BIISS to affect 10–19% of adolescents and 7% of adults (Lee et al., 2012; Pallesen et al., 2011), which puts our prevalence of BISS on the lower end of the adolescent spectrum. Given college students’ sleep biology, their proclivity to stay up and sleep late, and the college pressure to curtail sleep for academics or social activities, it was hypothesized that BIISS’ rates would be more similar to adolescent than adult studies (Hershner & Chervin, 2014; Klerman & Dijk, 2005). The lower rate of BIISS may be attributable to the study’s conservative measurement of daytime sleepiness, wherein students reported likelihood of falling asleep while driving, eating meals, or engaging in social activity. Of note, prevalence rates of insomnia and BIISS did not change appreciably when under 7 hr was used as a cutoff for insufficient sleep instead of 6.5 hr or less.

Those with insomnia and BIISS did not significantly differ in terms of sleep duration. No group difference was expected, given that short sleep duration (≤ 6.5 hr) was used as a classifying criteria for both insomnia and BIISS. Insufficient sleep duration has been consistently linked to increased depressive symptoms (McKnight-Eily et al., 2011; Winsler, Deutsch, Vorona, Payne, & Szklo-Coxe, 2015). The similar sleep durations between insomnia and BIISS affirm that between-group differences on depressive symptoms were not attributable to sleep duration.

Daytime sleepiness was significantly more common in students with BIISS than in students with insomnia. Daytime sleepiness was a required diagnostic criterion for BIISS; however, daytime sleepiness was neither a requirement nor was it exclusionary for insomnia. Some individuals with insomnia also experience general hyperarousal, which could limit sleepiness during the day (Wollweber & Wetter, 2011). Differences in daytime sleepiness between insomnia and BIISS are meaningful because daytime sleepiness—even in the absence of other sleep-related symptoms—predicts depression (Hayley et al., 2013). In this study’s overall sample, daytime sleepiness was significantly correlated to depressive symptoms. Thus, for participants with BIISS, it is possible that daytime sleepiness may be a driving force for depressive symptoms.

Insomnia was associated with greater sleep-onset latency than BIISS, as participants with insomnia had a sleep latency of ~45 min compared to ~15 min for BIISS. As long sleep latency was required for insomnia categorization, group differences were anticipated. However, differences in sleep latency may have contributed to relative differences in depression severity between insomnia and BIISS. Previous research has proposed that sleep latency is a mechanism linking insomnia with depression, as long latency is associated with increased rumination and hopelessness as well as reduced self-efficacy (Taylor et al., 2013). Indeed, a key component of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is reducing sleep latency, which has been demonstrated to improve both sleep and depression (e.g., Manber, et al., 20,008). In the present overall sample, sleep latency was significantly correlated with depression. Thus, long sleep latency specific to insomnia may be a driving force behind the greater depressive symptoms in insomnia compared to BIISS.

Sleep and depression

The present study is the first to compare depression symptoms between insomnia and BIISS. Depressive symptoms were endorsed on average moderately to extremely by nearly one third of college students in this sample. These rates were commensurate with previous research on college student depression (Sarokhani et al., 2013). All sleep characteristics (onset latency, daytime sleepiness, quality, and duration) were significantly correlated with depressive symptoms. Insomnia was associated with the highest levels of depressive symptoms, followed by BIISS and then normal sleep, consistent with our hypotheses. Between-group differences (e.g., comparing insomnia to BIISS, BIISS to normal sleep, etc.) were statistically significant when depression was treated continuously. These results remained consistent when under 7 hr was used as a cutoff, per sensitivity analyses. Thus, insomnia, BIISS, and normal sleep differentially influence depressive symptoms.

In addition to analyzing depressive symptoms continuously by sleep group, depressive symptoms were analyzed dichotomously, comparing students with less than moderate depressive symptoms to students with moderate or greater depressive symptoms. Students with insomnia were twice as likely to have moderate or greater depressive symptoms, compared to students with normal sleep. Although students with BIISS were around 40% more likely to have moderate or higher depressive symptoms compared to normal sleepers, these findings were not statistically significant. These findings suggest that, while insomnia and BIISS are both associated with more depressive symptoms, only insomnia is associated with clinically significant depression. Given that sleep duration did not significantly differ between groups, it is likely that an aspect of insomnia, such as cognitive (e.g., hopelessness, lack of control, rumination) or biological components (e.g., physiological hyperarousal, genetic vulnerability related to serotonin, disrupted corticolimbic circuitry, inflammatory cytokine dysregulation) contributes to greater depressive symptoms (Blake, Trinder, & Allen, 2018).

Clinical implications, limitations, and future directions

The present study’s high prevalence of sleep problems, coupled with their relationship to depressive symptoms, has implications for screening and intervention. Despite widespread sleep issues, sleep-related screenings in student health centers are not routine. Assessment for both insomnia and BIISS in student health centers, in addition to campaigns for healthy sleep for college students, could prove beneficial. Given that both disorders were associated with greater depression, regardless of whether their insufficient sleep was defined as less than 7 hr or 6.5 hr or less, students with borderline insufficient sleep may benefit from screening for sleep habits, including BIISS or insomnia diagnoses. This is particularly important given that both depression and sleep issues are associated with other risky behaviors (e.g., unsafe sex, alcohol abuse), poor academic performance, detrimental health consequences (e.g., weight gain, pain), and increased suicide risk in college students (Centers for Disease Control, 2016). Abridged formats of CBT-I are effective in improving sleep, including for patients with psychiatric comorbidities, so future research should continue to investigate its benefit for those with depressive symptoms (Manber et al., 2008). Several of the mechanisms linking sleep disturbances and depression may warrant further exploration. For example, this study showed both that long sleep latency predicted depression and that insomnia predicted worse depression than BIISS. As shortening sleep latency is a key treatment goal of CBT-I, it would be interesting for further research to explore this potential relationship.

This study includes several methodological limitations. First, the data set consists entirely of self-report items, rather than a diagnostic interview or objective sleep measures, limiting our ability to formally diagnose participants with BIISS or insomnia or to establish degree of clinical impairment. Moreover, this study was not able to assess for sleep problems, such as sleep apnea or circadian disorders (due to not assessing sleep timing), both of which can be associated with depression. Additionally, we could not evaluate whether these students had been diagnosed or treated for depression or sleep disorders. Moreover, substance use (e.g., alcohol use, nonmedical use of prescription drugs, or marijuana) that may have contributed to both sleep issues and depression was not evaluated in this study. Further, as this study is part of a larger investigation, measures were abridged, which limited comparison to clinical cutoff scores or established norms. Additionally, it is possible that students with depression perceived their sleep to be worse than students without depression. Because only one cohort of data was available at time of analysis, sleep and depressive symptoms were assessed concurrently, limiting our ability to establish directionality between sleep issues and depression. Future research may build on the present study by including clinical interviews and objective sleep measurement, in addition to longitudinal design. Additionally, future research should evaluate between group differences in insomnia and BIISS on other prevalent comorbid mental health concerns, such as anxiety, as well as on physical health. Existing literature has established that these concerns are prevalent and related to insufficient sleep, but research has not yet established whether this link is due to insomnia or if it is behaviorally induced insufficient sleep (e.g., Alvarez & Ayas, 2004; Cox & Olatunji, 2016).

In summary, the present study characterized sleep in college students, with a focus on insomnia and BIISS and their relationship to depression. In the sample, college students’ sleep was commonly insufficient in duration, with fairly good sleep quality, normal sleep latency, and high levels of daytime sleepiness. In this sample, 67.7% had normal sleep, 22.1% reported insomnia symptoms, and 9.9% reported BIISS symptoms. Individuals with insomnia reported the greatest depression symptoms, followed by BIISS and normal sleep, with significant differences between groups. Additionally, the insomnia group was at roughly double the risk for having moderate or higher symptoms of depression when compared to normal sleepers. Taken collectively, these findings emphasize the prevalence of poor sleep in college students as well as the potential consequences on depression. Further research is needed to understand longitudinal trajectories of insomnia and BIISS on depression and to parse out pathways from these sleep disorders to depression.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The VCU Student Survey has been supported by Virginia Commonwealth University, P20 AA107828, R37AA011408, K02AA018755, and P50 AA022537 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and UL1RR031990 from the National Center for Research Resources and National Institutes of Health Roadmap for Medical Research (PIs: Danielle Dick and Kenneth Kendler). Research reported in this publication was also supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23AG049955 (PI: Joseph Dzierzewski). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Alvarez GG, & Ayas NT (2004). The impact of daily sleep duration on health: A review of the literature. Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing, 19(2), 56–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. (2005). International classification of sleep disorders, 2nd ed: Diagnostic and coding manual. Westchester, IL: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American College Health Association. (2006). National college health assessment fall 2006 reference group executive summary. Retrieved from http://www.acha-ncha.org/docs/ACHA-NCHA_Reference_Group_ExecutiveSummary_Fall2006.pdf

- Baglioni C, Battagliese G, & Feige B (2011). Insomnia as a predictor of depression: A meta- analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 135, 10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake MJ, Trinder JA, & Allen NB (2018). Mechanisms underlying the association between insomnia, anxiety, and depression in adolescence: Implications for behavioral sleep interventions. Clinical Psychology Review, 63, 25–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, & Kupfer DJ (1989). The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research, 28(2), 193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carskadon MA, Acebo C, & Seifer R (2001). Extended nights, sleep loss, and recovery sleep in adolescents. Arch ives Italiennes de Biologie, 139, 301–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016). Healthy people 2020. Retrieved from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/sleep-health

- Clark SW (2015). Predicting Depression Symptoms Among College Students: The Influence of Parenting Style.

- Cortina JM (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(1), 98–104. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.98 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RC, & Olatunji BO (2016). A systematic review of sleep disturbance in anxiety and related disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 37, 104–129. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley SJ, Acebo C, & Carskadon MA (2007). Sleep, circadian rhythms, and delayed phase in adolescence. Sleep Medicine, 8(6), 602–612. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, & Cleary PA (1977). Confirmation of the dimensional structure of the SCL- 90: A study in construct validation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 33(4), 981–989. doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1097-4679 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Nasim A, Edwards AC, Salvatore JE, Cho SB, Adkins A, … Kendler KS (2014). Spit for Science: Launching a longitudinal study of genetic and environmental influences on substance use and emotional health at a large US university. Frontiers in Genetics, 5(47), 1–12. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaultney JF (2010). The prevalence of sleep disorders in college students: Impact on academic performance. Journal of American College Health, 59, 91–97. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.483708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gress-Smith JL, Roubinov DS, Andreotti C, Compas BE, & Luecken LJ (2015). Prevalence, severity and risk factors for depressive symptoms and insomnia in college undergraduates. Stress and Health, 31(1), 63–70. doi: 10.1002/smi.2509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde G (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)- A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Information, 42(2), 377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayley AC, Williams LJ, Berk M, Kennedy GA, Jacka FN, & Pasco JA (2013). The relationship between excessive daytime sleepiness and depressive and anxiety disorders in women. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 47(8), 772–778. doi: 10.1177/0004867413490036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershner SD, & Chervin RD (2014). Causes and consequences of sleepiness among college students. Nature and Science of Sleep, 6, 73–84. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S62907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klerman EB, & Dijk DJ (2005). Interindividual variation in sleep duration and its association with sleep debt in young adults. Sleep, 28, 1253–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ, Cho SJ, Cho IH, & Kim SJ (2012). Insufficient sleep and suicidality in adolescents. Sleep, 35(4), 455–460. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund HG, Reider BD, Whiting AB, & Prichard JR (2010). Sleep patterns and predictors of disturbed sleep in a large population of college students. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 46(2), 124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai E, & Buysse DJ (2008). Insomnia: Prevalence, impact, pathogenesis, differential diagnosis, and evaluation. Sleep Medicine Clinics, 3(2), 167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2008.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manber R, Edinger JD, Gress JL, Pedro-Salcedo MG, Kuo TF, & Kalista T (2008). Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia enhances depression outcome in patients with comorbid major depressive disorder and insomnia. Sleep, 31(4), 489–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall WV, & Black CG (2013). The link between suicide and insomnia: Theoretical mechanisms. Current Psychiatry Reports, 15(9), 1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11920-013-0389-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight-Eily LR, Eaton DK, Lowry R, Croft JB, Presley-Cantrell L, & Perry GS (2011). Relationships between hours of sleep and health-risk behaviors in US adolescent students. Preventive Medicine, 53(4), 271–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M, Kirchner HL, Drotar D, Johnson N, Rosen C, Ancoli-Israel S, & Redline S (2009). Relationships among sleepiness, sleep time, and psychological functioning in adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34(10), 1175–1183. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowbray CT, Megivern D, Mandiberg JM, Strauss S, Stein CH, & Collins K, ... & Lett R (2006). Campus mental health services: recommendations for change. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76(2), 226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadorff MR, Nazem S, & Fiske A (2011). Insomnia symptoms, nightmares, and suicidal ideation in a college student sample. Sleep, 34(1), 93–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Sleep Foundation. (2015). National sleep foundation recommends new sleep times. [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.sleepfoundation.org/press-release/national-sleep-foundation-recommendsnew-sleep-times

- Oginska H, & Pokorski J (2006). Fatigue and mood correlates of sleep length in three age social groups: School children, students, and employees. Chronobiology International, 23(6), 1317–1328. doi: 10.1080/07420520601089349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallesen S, Saxvig IW, Molde H, Sorensen E, Wilhelmsen-Langeland A, & Bjorvatn B (2011). Brief report: Induced insufficient sleep syndrome in older adolescents: Prevalence and correlates. Journal of Adolescence, 34(2), 391–395. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regestein Q, Natarajan V, Pavlova M, Kawasaki S, Gleason R, & Koff E (2010). Sleep debt and depression in female college students. Psychiatry Research, 176(1), 34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemann D, & Voderholzer U (2003). Primary insomnia: A risk factor to develop depression?. Journal of Affective Disorders, 76(1), 255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarokhani D, Delpisheh A, Veisani Y, Sarokhani MT, Manesh RE, & Sayehmiri K (2013). Prevalence of depression among university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis study. Depression Research and Treatment, 2013, 1–7. doi: 10.1155/2013/373857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutte-Rodin S, Broch L, Buysse D, Dorsey C, & Sateia M (2008). Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 4(5), 487. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shochat T, Cohen-Zion M, & Tzischinsky O (2014). Functional consequences of inadequate sleep in adolescents: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 18(1), 75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2013.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Peacey V, & Wardle J (2006). Sleep duration and health in young adults. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(16), 1689–1692. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.16.1689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DJ, Bramoweth AD, Grieser EA, Tatum JI, & Roane BM (2013). Epidemiology of insomnia in college students: Relationship with mental health, quality of life, and substance use difficulties. Behavior Therapy, 44 (3), 339–348. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DJ, Gardner CE, Bramoweth AD, Williams JM, Roane BM, Grieser EA, & Tatum JI (2011). Insomnia and mental health in college students. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 9, 107–116. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2011.557992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittier A, Sanchez S, Castañeda B, Sanchez E, Gelaye B, Yanez D, & Williams MA (2014). Eveningness chronotype, daytime sleepiness, caffeine consumption, and use of other stimulants among Peruvian university students. Journal of Caffeine Research, 4(1), 21–27. doi: 10.1089/jcr.2013.0029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winsler A, Deutsch A, Vorona RD, Payne PA, & Szklo-Coxe M (2015). Sleepless in Fairfax: The difference one more hour of sleep can make for teen hopelessness, suicidal ideation, and substance use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(2), 362–378. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0170-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollweber BT, & Wetter TC (2011). Review articles-A brief review of neurobiological principles of insomnia. Schweizer Archiv fur Neurologie und Psychiatrie, 162(4), 139. doi: 10.4414/sanp.2011.02274 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (1992). The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: Author. [Google Scholar]