Abstract

Background:

Numerous anecdotal reports suggest that repeated use of very low doses of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), known as “microdosing,” improves mood and cognitive function. These effects are consistent both with the known actions of LSD on serotonin receptors, and with limited evidence that higher doses of LSD (100-200 μg) positively bias emotion processing. Yet, the effects of such sub-threshold doses of LSD have not been tested in a controlled laboratory setting. As a first step, we examined the effects of single very low doses of LSD (0 - 26μg) on mood and behavior in healthy volunteers under double-blind conditions.

Methods:

Healthy young adults (N=20) attended four laboratory sessions during which they received placebo, 6.5 μg, 13μg, or 26μg LSD in randomized order at one-week intervals. During expected peak drug effect, they completed mood questionnaires and behavioral tasks assessing emotion processing and cognition. Cardiovascular measures and body temperature were also assessed.

Results:

LSD produced dose-related subjective effects across the three doses (6.5μg, 13μg, or 26μg). At the highest dose the drug also increased ratings of “vigor” and slightly decreased positivity ratings of images with positive emotional content. Other mood measures, cognition, and physiological measures were unaffected.

Conclusions:

Single “microdoses” of LSD produced orderly dose-related subjective effects in healthy volunteers. These findings indicate that a threshold dose of 13 μg of LSD might be used safely in an investigation of repeated administrations. It remains to be determined whether the drug improves mood or cognition in individuals with symptoms of depression.

Keywords: LSD, microdosing, behavior, emotion, psychopharmacology, mood

Introduction

There has been a great deal of public interest in the phenomenon of “microdosing” LSD to improve mood and cognitive function (1–3). Users claim that very low doses of LSD (5-20 μg) taken at 35-day intervals improve depressed mood and positive outlook, and perhaps also improve cognitive function. The phenomenon has received widespread coverage, including reports in the New York Times, the Atlantic, and the New Yorker, as well as in recent books (4, 5). Although several naturalistic studies have been conducted to monitor users’ experiences with the drug in non-controlled settings (6), there have been few controlled studies with double-blind drug administration and placebo.

The pharmacology of LSD is fairly well documented. Like many approved medications for the treatment of depression, LSD has its primary effects on the serotonin system, specifically the 5HT2A receptors (7), although the drug also binds at several other serotonin receptors including 5-HT1A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT5A, and 5-HT6 (8). LSD is of natural origin, obtained by hydrolysis of ergot alkaloids, which are produced by the ergot (Claviceps) fungus. Its primary psychoactive effects are thought to be related partial agonist actions at 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors, and some behavioral actions have been linked to dopamine D2 receptors (9, 10). Although the psychedelic effects of LSD and other 5-HT2A agonists are blocked by 5-HT2A antagonists (11, 12), less is known about the binding profiles of the very low doses. LSD remains bound to receptors for a long time, which may be responsible for its long duration of effect and may contribute to its reported therapeutic value with doses administered at 3-5 day intervals (13). The effects of high doses of LSD (100-200 μg) can last as long as 12 hours. There is a detectable metabolite, 2-oxo-3-hydroxy-LSD (O-H-LSD), but its pharmacological activity is not known (14). The safety of LSD has been well documented over decades of research and experience, including at doses many-fold higher than those proposed here (8).

The use of LSD as an antidepressant has a long history. In the 1950s and 1960s, over 1,000 studies were published supporting therapeutic effects of LSD in combination with psychotherapy for disorders such as depression (15, 16). However, many of these early studies lacked adequate control groups, and did not isolate drug effects from effects of the psychotherapy itself. More recently, preclinical studies show that LSD exerts antidepressant-like effects in animal models (17), and a small number of recent studies in humans have shown that high doses of the drug (200-800μg) are effective in reducing psychiatric symptoms, including end-of-life anxiety in terminally ill patients and addictive disorders in drug users (18, 19). Some of the positive emotional effects of LSD, such as optimism, reportedly persist for weeks after administration of a moderately high dose (20). It should be noted that these studies are typically conducted in the safe, pleasant environment of a testing room furnished with welcoming decor, pleasant music, and an effort to create a relaxing atmosphere. In less predictable environments, LSD can produce less positive and even negative emotional effects, though there are limited data on the connection between environment and emotional experience on the drug (21).

Several recent controlled studies have described the behavioral and neural effects of high doses of LSD (100-200 μg) in healthy adults (11, 12, 22–26). Although such high doses would be impractical for a regularly-dosed therapeutic drug used in naturalistic settings because of perceptual distortions and impaired inhibitory control, it is interesting to note that the high doses produce some possibly beneficial emotional effects, such as reduced reactivity to fearful faces and increase feelings of trust and closeness to others.

There have also been reports that LSD improves cognitive function. This is consistent with reports that improved cognition often accompanies improved mood (2, 3, 6), and there is evidence that LSD can enhance learning in animal models of depression (17). 5HT2A signaling is known to be involved in learning (27), and intrahippocampal administration of LSD enhances associative learning in rabbits (28). Improvements in cognitive function would be consistent with cellular findings by (29) that LSD and other ‘psychedelic’ drugs increase dendritic arbor complexity, promote growth of dendritic spines, and stimulate formation of synapses (16).

Several studies have examined the effects of low doses of psychedelic drugs in human volunteers, either in single doses under controlled conditions or with repeated doses under naturalistic conditions. For example, (30) used a between-subject design in a controlled setting to examine the effects of LSD (0, 5, 10 and 20 micrograms) on perception of time in older adults, aged 55 to 75. Subjects over-estimated time intervals of 2 seconds and longer after the 10 microgram dose. Prochazkova et al. (31) conducted an unblinded naturalistic study using estimated doses of psilocybin or psilocin during a group social event, to assess the effects of the drug on creativity-related problem solving tasks. Participants reported that the drug increased cognitive fluency, flexibility, and originality without affecting analytic cognition. In perhaps the most comprehensive naturalistic study to date, the authors obtained extensive questionnaire data from about 350 individuals who reported microdosing, assessing both actual experiences and expected effects of using the psychedelic drugs on measures of mood, attention, mind-wandering and wellbeing. Participants reported transient enhanced mood and wellbeing (6). Although the participants described strongly held beliefs about the beneficial effects of microdosing, these expectancies did not always align with the actual reports of beneficial effects after using the drug.

The study presented here addresses a gap in our knowledge about the acute effects of very low doses of LSD on mood, cognition and affective responses responses to stimuli with emotional valence. We tested the mood-altering, physiological and behavioral effects of three low doses (6-26 micrograms) of LSD in young adults in a double-blind, within-subject placebo-controlled laboratory. Understanding the acute effects of a drug is a first step to investigating the effects of repeated doses in clinical populations.

Methods

Study Design

The study used a within-subject, double blind design consisting of four sessions wherein healthy young adults received, in counterbalanced order, 0 (placebo), 6.5, 13, or 26 micrograms (μg) of LSD. Subjective mood states and physiological measures were recorded at baseline before drug administration and then at 30-90 min intervals after drug administration, and at the time of peak drug effect subjects completed behavioral tasks assessing cognition and affective responses to emotional stimuli. Sessions were conducted in private living-room style laboratory rooms equipped with a couch, table, and computer for testing. Between measurements, participants were allowed to relax, read, or watch movies.

Subjects

Healthy subjects (N=20, 12 women) ages 18 - 40 were recruited from the community. Screening consisted of a physical examination, electrocardiogram, modified Structural Clinical Interview for DSM-V and self-reported health and drug-use history. Inclusion criteria were: English fluency, at least a high school education, BMI of 19–26, no current or past year DSM-V disorders, no past year drug or alcohol dependence, not currently pregnant or nursing, no night shift work, no regular medication aside from birth control, and at least one use of a psychedelic drug which we defined as MDMA, LSD, psilocybin, DMT, or others considered on a case-by-case basis. Subjects were excluded if they had an adverse reaction to a psychedelic drug resulting in an unwillingness to use the drug again.

Subjects were required to abstain from drugs and medications for 48 hours before and 24 hours after each session. In addition, they were instructed to abstain from cannabis seven days before and 24 hours after each session, and to abstain from alcohol for 24 hours before and 12 hours after each session. They were permitted to consume their normal amounts of caffeine and nicotine before and after the session. Subjects were instructed to have a normal night’s sleep, and fast for 12 hours before the sessions. A granola bar was provided at arrival, and lunch was provided 240 minutes after drug administration. They were not permitted to drive, bike, or operate machinery for 12 hours after each session. Subjects were told they might receive a placebo, stimulant, sedative, or hallucinogen drug. All subjects provided informed consent prior to beginning the study procedures, which were approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board.

Procedure

Orientation session.

Subjects attended an orientation session to review the protocol, provide informed consent, receive pre-session instructions and practice study tasks and questionnaires.

Drug sessions.

Subjects attended four 8-hour experimental sessions beginning at 9:00 AM and separated by at least 7 days. Compliance to drug abstinence instructions was verified by urinalysis (CLIAwaived Instant Drug Test Cup, San Diego, CA) and breath alcohol testing (Alcosensor III, Intoximeters, St. Louis, MO). Female subjects provided urine samples for pregnancy tests. After compliance was confirmed, baseline measures of subjective state and cardiovascular function were obtained. LSD (6.5, 13, and 26 μg; Organix, Inc.) or placebo (water) was administered sublingually at 9:30 AM. The drug was administered under double-blind conditions, in a volume of 0.5 ml, consisting of water and the appropriate volume of LSD solution. The subject held the solution under the tongue without swallowing for 60 seconds, under observation by the research assistant. Subjective and cardiovascular measures were taken at 10:30 and 11:30 AM, and 1, 2, 3:30 and 4:30 PM. At noon, subjects completed a battery of behavioral tasks including measures of affective responses to emotional stimuli as well as a measure of working memory. At 1:10 PM lunch was provided. At 4:30 PM subjects completed an end of session questionnaire. Subjects were also asked to complete a mood questionnaire 48 hours after each session to detect lasting alterations in mood.

Drug

The drug was manufactured by Organix, Inc. (MA), and prepared in solution with tartaric acid by the University of Chicago Investigational Pharmacy. The drug was administered sublingually. The doses were selected to be below the threshold for hallucinatory effects, and within the range that is used in naturalistic settings. A recent comprehensive survey indicated that the average dose used for microdosing LSD is 13.5μg (6). The onset of action after oral LSD is 30 minutes, with a peak plasma concentration at 1.5-3 hours and half-life of 9 hours (32).

Subjective and Cardiovascular Drug Effects

Subjective and physiological measures were obtained to monitor the effects of the drug. Standardized questionnaires were used to assess mood and drug effects.

Drug Effects Questionnaire (DEQ; 33):

The DEQ consists of five questions assessing subjective drug effects using 100mm Visual Analog Scales: do you feel a drug effect, like the drug effect, feel high, want more of what you received, or dislike the drug effect.

Addiction Research Center Inventory (ARCI; 34):

The ARCI consists of 49 “True-False” questionnaires with 5 subscales of drug-like effects: A (amphetamine-like, stimulant effects), BG (benzedrine group, energy and intellectual efficiency), MBG (morphine-benzedrine group, euphoric effects), LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide), and PCAG (pentobarbital-chlorpromazine-alcohol group, sedative effects).

Profile of Mood States (POMS; 35):

The POMS was originally our primary outcome measure. It was administered before drug administration and at 120 and 360 minutes. It consists 72 mood adjectives rated on a Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely), divided into subscales assessing Anxiety, Depression, Anger, Vigor, Fatigue, Confusion, Friendliness and Elation. The POMS Depression scale with two distractor items (cheerful and clear-headed) was used to assess mood via email, 48 hours after each session.

The 5 Dimensions of Altered States of Consciousness Questionnaire (5D-ASC; 36):

The 5D-ASC was administered once each session at 12:50 PM. It consists of 94 statements describing sensations typical of a psychedelic or mystical experience. Subjects respond to statements on a 100mm Visual Analog Scale indicating how they feel relative to their normal waking consciousness, the degree to which they experienced each item during that day’s session. Its five scales measure aspects of the psychedelic experience: Oceanic Boundlessness, Dread of Ego Dissolution, Visionary Restructuralization, Acoustic Alterations, and Vigilance Reduction.

Physiological, behavioral and cognitive measures (described in Supplementary Materials).

Heart rate and blood pressure were measured repeatedly during the sessions. The following behavioral and cognitive tasks were administered once during the session: the Dual N-Back (37) a measure of working memory, the Digit Symbol Substitution Task (DSST) a measure of cognitive functioning, “Cyberball” task a measure of simulated social exclusion (38), the Emotional Images Task in which participants rate positive, negative, and neutral emotional images from the International Affective Picture System (39) using an evaluative space grid (40), and a Remote Associations Task (RAT) measuring convergent thinking, an aspect of creativity (41).

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were conducted using SPSS. Missing cases (due to equipment malfunction or other data collection problems) were deleted list-wise, which led to smaller sample sizes for some analyses. Subjective and physiologic effects of the drug were assessed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), with dose and time as within-subjects factors and follow-up planned contrasts comparing each dose to placebo. Behavioral data from tasks were analyzed with repeated measures ANOVAs with dose as a within-subject factor and similar follow-up tests.

Results

Demographics

Subjects were in their mid-20’s (mean= 25 years) with an average of 3 years post-high school education (Table 1). They were mostly Caucasian (N=9), and reported moderate previous drug use experience.

Table 1.

Demographic and drug use of the participants (N=20).

| Category | Count or Mean ± SD (Range) |

|---|---|

| N (male/female) | 20 (8/12) |

| Age (years) | 25 ± 3 (19 - 30) |

| Education (years) | 15 ± 1 (12 – 16) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 25.1 ± 4.0 (18.0 – 31.3) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 9 |

| African-American | 4 |

| Asian | 1 |

| Other/More than One Race | 6 |

| DASS | |

| Depression | 2.1 ± 2.4 (0 – 8.0) |

| Anxiety | 1.7 ± 2.0 (0 – 6.0) |

| Stress | 3.6 ± 2.9 (0 – 11.0) |

| Current Drug Use (past month) | |

| Caffeine (servings/day) | 1.8 ± 2.1 (0 – 7.9) |

| Tobacco | |

| Smokers/non-smokers | 6/14 |

| Cigarettes/ day (smokers only) | 1.4 ± 1.0 (0.2 – 2.5) |

| Alcohol (drinks/ week) | 3.4 ± 2.8 (0 – 13.0) |

| Alcohol (drinking days/ week) | 2.7 ± 2.0 (0 – 7.0) |

| Cannabis (times/ month) | 14.0 ± 16.2 (0 – 60.0) |

| Lifetime Drug Use | |

| Stimulant | 14.1 ± 18.7 (0 – 60.0) |

| Tranquilizer | 12.0 ± 44.4 (0 – 200.0) |

| Opiate | 8.1 ± 22.1 (0 – 93.0) |

| MDMA, Ecstasy, Molly | |

| Never used | 1 |

| 1 – 5 times | 11 |

| 6 – 20 times | 6 |

| 21 – 70 times | 2 |

| LSD | |

| Never used | 6 |

| 1 – 5 times | 10 |

| 6 – 20 times | 4 |

| Psilocybin or mescaline | |

| Never used | 6 |

| 1 – 5 times | 11 |

| 6 – 20 times | 3 |

| Other Psychedelic (DMT, Salvia, Ketamine, Peyote) | |

| Never used | 14 |

| 1 – 5 times | 3 |

| 6 – 20 times | 3 |

Subjective effects

DEQ

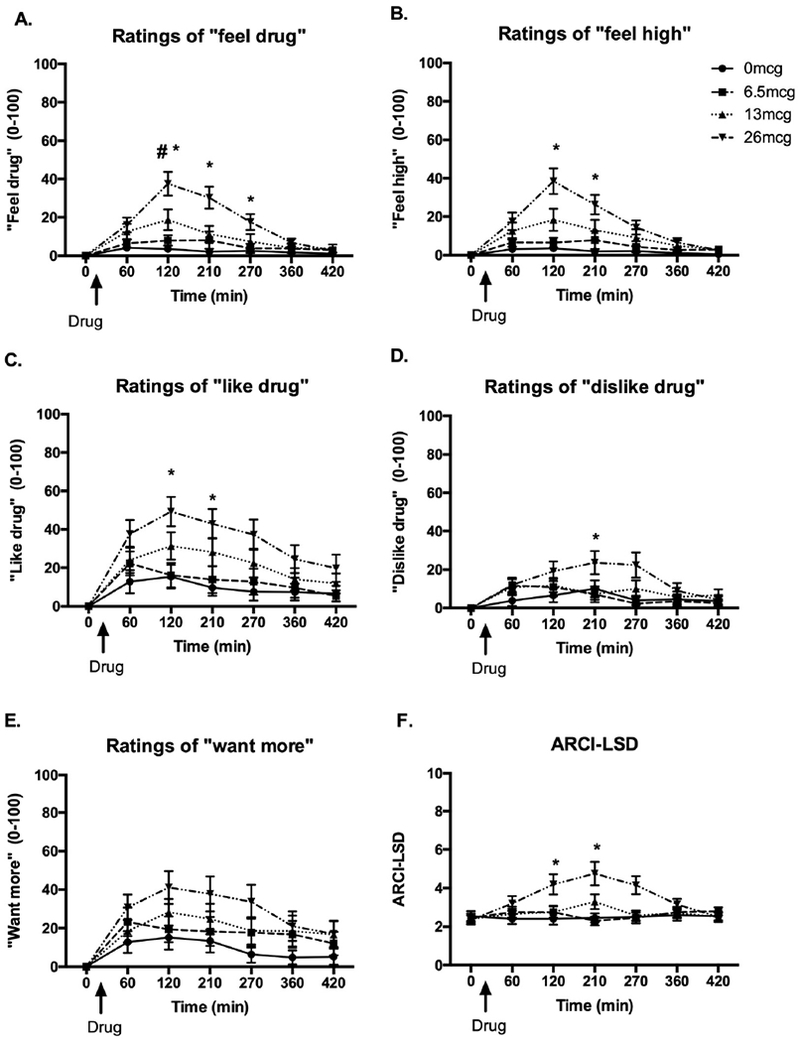

LSD (13μg and 26μg) significantly increased ratings of “feel drug” on the Drug Effects Questionnaire [Figure 1a: Dose × Time F(18,342)=10.36, p<0.001; 26μg vs. placebo p<0.001 at 120min and 180min, p<0.01 at 240min and 13μg vs. placebo p<0.05 at 120min]. LSD (26μg) increased ratings of “feel high” [Figure 1b: Dose × Time F(18,342)=8.48, p<0.001; 26μg vs. placebo p<0.001 at 120min and 180min] and “like drug” [Figure 1c: Dose × Time F(18,342)=2.34, p<0.01; 26μg vs. placebo p<0.01 at 120min]. The 26μg dose also significantly increased ratings of “dislike drug” [Figure 1d: Dose × Time F(18,342)=2.30,p<0.01; 26μg vs. placebo p<0.05 at 240min]. There was a trend toward a dose × time interaction on “Want More” [Figure 1e: F(18,342)=1.49, p=0.09].

Figure 1: Effects of LSD on subjective reports of a) “feel drug,” b) “feel high,” c) “like drug,” d) “dislike drug,” e) “want more,” and f) ARCI-LSD scale.

Bars depict mean ± SEM. *signifies significant difference 26ug vs. placebo p<0.01, # signifies significant difference 13ug vs. placebo p<0.05.

ARCI

LSD (26 μg) increased scores on the LSD scale, compared to placebo [Figure 1b: Dose × time; ARCI-LSD F(18,342)=4.13, p<0.001; 26μg vs. placebo p<0.05 at 120min and p<0.01 at 180min]. There were no significant drug effects on ARCI A, MBG, BG, or PCAG scales.

POMS

On the POMS, LSD (26μg) significantly increased ratings of Vigor, relative to placebo [Dose F(3,57)=5.14, p<0.01; 26μg vs. placebo p<0.05]. On POMS ratings of Friendliness, there was a main effect of dose [F(3,57)=2.80, p<0.05] but follow up tests did not reach significance. On the POMS Anxiety scale there was a main effect of dose and a trend for the highest dose to increase ratings [F(3,57)=3.24, p<0.05; 26μg vs. placebo p=0.051]. The drug did not significantly affect Elation, Depression, Anger, Fatigue, or Confusion scales (Table 2).

Table 2.

Means and SDs for outcomes of subjective ratings of mood and behavioral tasks.

| Placebo | 6.5μg | 13μg | 26μg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image Rating (1-6) | ||||

| Positive | 2.00(0.5) | 2.02(0.48) | 1.86(0.43)* | 1.78(0.53) |

| Neutral | 1.10(0.57) | 1.20(0.54) | 1.14(0.50) | 1.06(0.56) |

| Negative | 0.32(0.24) | 0.35(0.29) | 0.38(0.32) | 0.39(0.31) |

| Face Identification (s) | ||||

| Angry | 11.18(3.17) | 10.67(2.58) | 10.56(3.53) | 10.83(2.63) |

| Sad | 8.03(2.31) | 7.30(1.81) | 8.29(2.55) | 7.97(1.94) |

| Happy | 7.76(2.41) | 7.24(2.25) | 7.89(2.84) | 7.38(1.68) |

| Fearful | 8.39(2.58) | 7.51(2.29) | 8.72(3.01) | 8.53(3.42) |

| Disgust | 7.07(2.47) | 7.90(2.60) | 7.32(2.89) | 7.31(2.61) |

| Surprise | 7.66(1.38) | 7.76(1.65) | 7.82(1.98) | 7.96(2.43) |

| Cyberball (Positive mood 1-100) | ||||

| Accept | 27.4(4.32) | 27.10(4.15) | 28.05(4.00) | 28.00(5.05) |

| Reject | 18.80(6.89) | 19.05(6.50) | 18.80(6.57) | 18.95(7.03) |

| N-Back | ||||

| Correct (N) | 19.00(1.6) | 19.17(1.4) | 19.35(1.60) | 19.6(2.2) |

| RT (ms) | 2595.72 (132.93) | 2602.91 (142.48) | 2601.27 (111.48) | 2601.47 (123.81) |

| DSST | ||||

| Correct(N) | 71.74(14.64) | 72.30(11.36) | 72.30(12.71) | 70.65(11.46) |

| Attempted (N) | 71.74(14.64) | 72.40(11.37) | 72.35(12.70) | 70.40(11.75) |

| Remote Associates | ||||

| Correct (N) | 7.10(2.22) | 7.55(1.54) | 7.60(2.40) | 7.6(2.28) |

| Attempted (N) | 14.20(4.25) | 15.20(3.19) | 15.35(4.02) | 15.70(4.08) |

| POMS (peak change from baseline) | ||||

| Depression | −0.20(1.40) | 0.30(1.71) | −0.35(2.50) | 1.15(2.71) |

| Anxiety | −0.55(2.11) | −1.35(4.73) | 0.00(4.78) | 1.70(4.75) |

| Friendliness | −2.80(3.97) | −0.95(6.14) | −1.80(5.26) | −0.50(6.72) |

| Vigor | −4.13(5.80) | −2.40(6.73) | −2.55(6.30) | −1.45(11.08) |

| Anger | −0.25(0.97) | −0.50(1.61) | 0.40(2.34) | 0.20(2.83) |

| Fatigue | 1.13(3.56) | 0.25(3.47) | 0.40(3.46) | 1.10(4.81) |

| Confusion | −0.20(1.82) | −0.10(1.41) | 0.45(2.26) | 1.50(3.12) |

| Elation | −1.88(4.62) | −1.75(4.47) | −0.40(4.99) | −0.80(5.18) |

| POMS Depression Follow-Up (N=11) | 7.45(7.59) | 6.73(7.32) | 7.45(11.79) | 7.36(11.54) |

indicates a significant difference from placebo, p<0.05.

5D-ASC

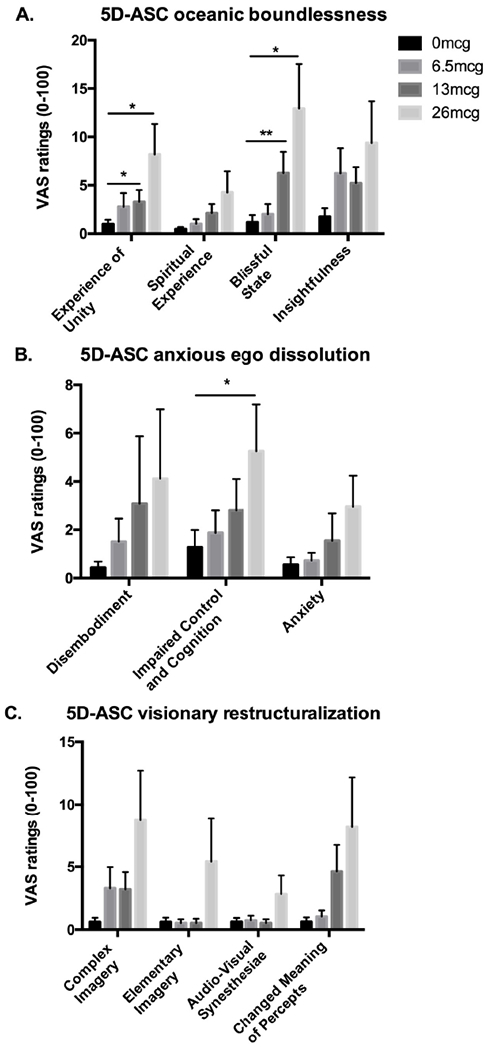

On the 5D-ASC administered at the end of each session, LSD dose-dependently increased ratings on the scales of Experience of Unity [Figure 3a: Dose F(3,57)=3.53, p<0.05; 13μg vs. placebo p<0.05 and 26μg vs. placebo p<0.05], Blissful State [Figure 3a: Dose F(3,57)=6.71, p<0.01; 13μg vs. placebo p<0.01 and 26μg vs. placebo p<0.05], Impaired Control and Cognition [Figure 3b: Dose F(3,57)=2.94, p<0.05; 26μg vs. placebo p<0.05], and Changed Meanings of Percepts [Figure 3c: Dose F(3,57)=2.85, p<0.05], though follow up tests did not reveal a significant dose effect. LSD also tended to increase ratings of Spiritual Experience, Insightfulness, Complex Imagery [Dose SE F(3,57)=2.40, p=0.08, I F(3,57)=2.64, p=0.06, CI F(3,57)=2.43, p=0.08]. There were no significant linear drug effects on Disembodiment, Anxiety, Elementary Imagery, Audiovisual Synesthesiae.

Figure 3: Effect of LSD on the 5D-ASC ratings on domains of a) oceanic boundlessness, b) anxious ego dissolution, and c) visionary restructuralization.

Bars depict mean ± SEM. * indicates significant different from placebo p<0.05. ** indicates significant different from placebo p<0.01.

Follow-up questionnaire

On the followup questionnaire administered 48 hours after each session there were no significant effects of dose. However, because these questionnaires were sent via email and did not require an additional laboratory visit, only 11 of the 20 subjects completed all four follow up questionnaires.

Physiological effects

LSD (13μg and 26 μg) significantly increased systolic blood pressure from 105.35 mm Hg on the placebo session to a peak of 111.5 at 13μg and 115.3 at 26μg [Dose × Time F(18,342)=1.68, p<0.05; at 120min and 180min 26μg vs. placebo p<0.01, at 120min 13μg vs. placebo p<0.05] and 26μg significantly increased diastolic blood pressure [Dose × Time F(18,342)=1.72, p<0.05; 26μg vs. placebo at 120min p<0.01]. The drug did not significantly affect heart rate or basal body temperature.

Emotion processing tasks.

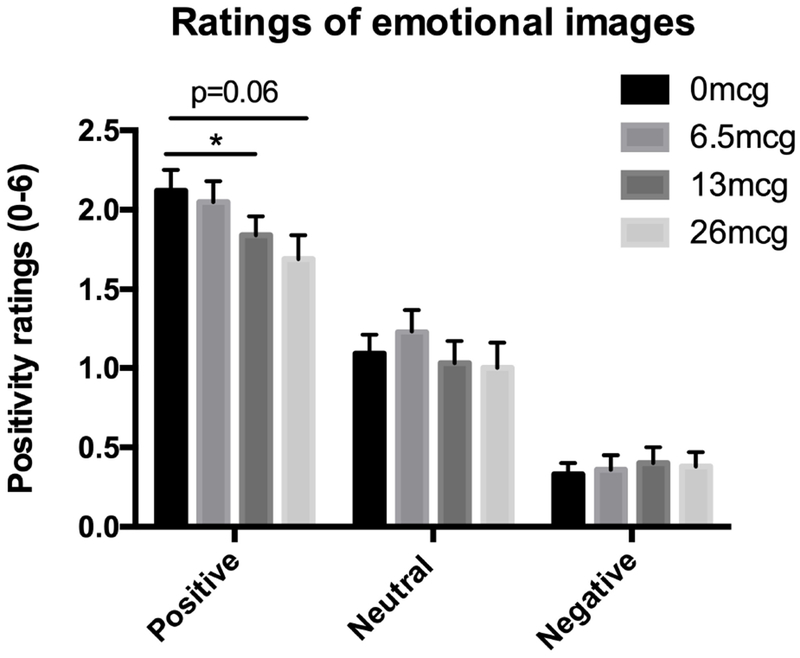

The tasks produced their expected effects on dimensions of emotional processing, but LSD had little effect on task performance (see Supplementary Materials). The only apparent drug effects were on the Emotional Images Task a marginal decrease in positivity ratings for positive pictures observed at the highest dose (Figure 2), and on the Remote Associates task a marginal increase in attempted trials.

Figure 2: Effects of LSD on ratings of emotional images.

Bars depict mean ± SEM. * indicates significant different from placebo p<0.05.

Drug Identifications

During the placebo session, 14 participants correctly guessed they had received placebo [incorrect guesses sedative (N=5) or cannabinoid (N=1)]. During the 6.5 μg dose session, no participants correctly guessed they had received a hallucinogen [incorrect guesses placebo (N=9), a stimulant (N=4), a sedative (N=4), opioid (N=1), or cannabinoid (N=2)]. During the 13 μg dose session 2 out of the 20 participants correctly guessed what they received [incorrect guesses placebo (N=9), a stimulant (N=3), a sedative (N=4), or opioid (N=1)]. During the 26μg dose session 6 participants correctly guessed they received a hallucinogen [incorrect guesses stimulant (N=6), sedative (N=2), cannabinoid (N=3), opioid (N=1), or placebo (N=2)].

Discussion

In this study we investigated the acute effects of very low ‘microdoses’ of LSD on mood, cognition, and behavior in healthy young adult volunteers, and identified the threshold doses at which LSD produces detectable subjective effects. We report that at doses one tenth to one twentieth those used recreationally (and more recently in therapeutic settings), LSD produces measurable modest increases in ratings of drug effects scales. At these doses, LSD also had subtle effects on behavioral tasks: tending to increase the number of attempted trials on a creativity task (the Remote Associates Test). This is the first controlled study to investigate the acute subjective and behavioral effects of microdoses of LSD using a placebo-controlled within subjects design in healthy young adult volunteers.

Doses of 13 and 26μg LSD produced measurable subjective and physiological effects. The effects were linearly dose-related across all three doses, and 26μg LSD significantly increased ratings of “feel drug,” “like drug,” “feel high,” and “dislike drug,” and scores on the ARCI-LSD scale and the Vigor scale on the POMS. Interestingly, the drug also produced dose-dependent alterations of consciousness as measured by the 5D-ASC, which had previously only been shown at 100-200 μg doses (42). Physiologically, the 26μg dose increased blood pressure, but did not significantly affect temperature or heart rate. Previous studies have shown that 200ug LSD increase heart rate, blood pressure, and body temperature (23), but the present findings reveal the threshold dose at which LSD produces these effects. This profile of responses to very low doses of LSD extend our understanding of the basic pharmacology of the drug, and set the stage for future studies on the behavioral and physiological effects of repeated doses of LSD.

There is some evidence that higher doses of LSD combined with psychotherapy can have beneficial effects on mood. Case reports and studies from the 1950s and 1960s suggest that LSD may be effective in a clinical context (reviewed in 43), and recent studies are investigating 100-200 μg LSD in combination with psychotherapy for anxiety associated with life threatening illnesses (18). Our participants were healthy and without mood disturbances. It is possible that their increased ratings of “Vigor” after 26 ug could contribute to beneficial effects for patients in a psychotherapy setting, but this remains to be established in patient samples. The items on the Vigor subscale of the POMS include such adjectives as “lively,” “active,” “energetic,” “cheerful,” “alert,” “full of pep,” “carefree,” and “vigorous.” Although some of these effects may fit with the reported mood effects of “microdosers” in the community setting, the effects of repeated microdoses of LSD in clinical populations of symptomatic volunteers remain to be determined.

While single larger doses of LSD have been shown to have beneficial effects on mood, few studies have examined smaller doses administered at regular intervals. In rodents, repeated low doses of psilocin and ketamine reduce anxiety-like behavior (44, 45) and enhance learning in animal models of depression (17). Anecdotal reports in humans suggest that repeated (every 3 days) ingestion of microdoses of LSD enhance mood and reduce ratings of depression (1). A recent survey of 98 regular microdosers suggested that the drug improved psychological functioning including reductions in depression and stress and lower distractibility (6). Although we did not detect effects of single doses on mood or depression, it remains to be determined whether anti-depressant effects would be detected in individuals who report significant levels of depression.

Although some previous studies have suggested improvements in cognition, these were not detected here on the DSST or N-back tasks. Few studies have assessed acute effects of LSD on cognition. In one recent study LSD (100 μg) significantly increased “cognitive bizarreness” (46), and in another study LSD (10 μg) altered time perception, resulting in the over-reproduction of temporal intervals greater than 2 seconds (30). One recent naturalistic, open-label (pre-post) study, microdosing psilocybin-containing truffles improved convergent and divergent thinking without affecting analytic cognition on two creativity tasks (31). Although we found that LSD marginally increased the number of attempted trials on a measure of creativity, overall we detected minimal effects on cognitive function.

Several previous studies using higher doses of LSD have shown acute effects on emotion processing. One study showed that LSD (100-200μg) impaired recognition of fearful facial expressions (25), and in an fMRI study LSD (100 μg) dampened amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex reactivity to fearful faces (47). Interestingly, greater reduction in amygdala response was related to greater subjective drug effects. In another recent study the 5HT1A/2A agonist, psilocybin, at a relatively higher dose (0.215mg/kg) reduced feelings of social rejection during Cyberball (48). We did not observe similar results in our sample, perhaps because of drug or dose differences. Finally, we showed that microdoses of LSD decrease positivity ratings of positive images. This finding was surprising, and went against our hypothesis that the drug, in light of reports of antidepressant effects, may positively bias responses to affective stimuli. One possible explanation for our results is that LSD reportedly enhances global connectivity in the brain, giving rise to the phenomenon of “ego dissolution,” or a weakening of the boundary between the self and the universe (49). This increased connectivity between normally distinct networks (defaul-mode, salience, and frontoparietal attention networks) may affect perception of valenced stimuli, leading subjects to rate “positive” images as less positive.

Our study had a number of strengths. Most notably, we tested three doses of the drug, compared to placebo, under double-blind conditions in a controlled laboratory setting. The participants included men and women, who were free of other drugs or alcohol at the time of testing. We allowed 7 days for drug clearance between the sessions. We used standardized self-report questionnaires, emotion and cognitive tests and obtained physiological measures at regular intervals. Until now, the effects of these very low doses of LSD have been investigated mainly in naturalistic open-label studies and through surveys (6, 31, 50). Here we present a profile of the full range of responses to the acute doses of the drug, including subjective, behavioral, affective and cognitive, in healthy young adults. In line with the conclusions of (6), we conclude that the 13 μg dose would be optimal for a repeated dosing study, as it produced minimal subjective, behavioral or physiological effects that might interfere with normal function. The findings form a basis for future studies investigating repeated doses and doses in clinical populations, to determine the empirical basis of the purported therapeutic affects reported by regular users of these drugs.

The effects of low doses of LSD should be investigated when the drug is administered repeatedly, and in individuals who report negative affect. Individuals who report microdosing in their everyday lives take the drug every 3-5 days, and it is possible that the beneficial effects emerge only after repeated administration. This could be because of subtle pharmacokinetic accumulation of the drug, or it could be because of pharmacodynamic neural adaptations that occur over days. An important aim for future research will be to collect pharmacokinetic data, extending existing data with higher doses (32). Regular users claim that the drug improves mood and cognition, which raises the possibility that their normal mood and cognitive function were less than optimal before using the drug. Therefore, it is important to examine the effect of LSD, either in single doses or in repeated dosing regimens, in populations reporting clinical mood symptoms, such as anxiety or depression. Studies such as this, investigating the mood and cognitive effects of low doses of psychedelic drugs under controlled conditions will advance our understanding of the neural and behavioral processes underlying depressed mood, and could lead to new treatments.

Supplementary Material

Key Resource Table

| Resource Type | Specific Reagent or Resource | Source or Reference | Identifiers | Additional Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Add additional rows as needed for each resource type | Include species and sex when applicable. | Include name of manufacturer, company, repository, individual, or research lab. Include PMID or DOI for references; use “this paper” if new. | Include catalog numbers, stock numbers, database IDs or accession numbers, and/or RRIDs. RRIDs are highly encouraged; search for RRIDs at https://scicrunch.org/resources. | Include any additional information or notes if necessary. |

| Antibody | ||||

| Bacterial or Viral Strain | ||||

| Biological Sample | ||||

| Cell Line | ||||

| Chemical Compound or Drug | LSD | Organix Inc, MA | ||

| Commercial Assay Or Kit | ||||

| Deposited Data; Public Database | ||||

| Genetic Reagent | ||||

| Organism/Strain | healthy human volunteers, men and women | |||

| Peptide, Recombinant Protein | ||||

| Recombinant DNA | ||||

| Sequence-Based Reagent | ||||

| Software; Algorithm | ||||

| Transfected Construct | ||||

| Other |

Acknowledgements

The authors thank David Nichols, PhD, for his advice and support, and the University of Chicago Investigational Pharmacy for assistance in drug preparation. AKB was supported by a training grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (2T32GM007281), SS was supported by T32DA043469, and HdW was supported by NIDA DA02812.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosures

The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

The study is registered on clinicaltrials.gov as “Mood effects of serotonin agonists,” , https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03790358.

References

- 1.Fadiman J, Korb S (2019): Microdosing Psychedelics. Advances in Psychedelic Medicine: State-of-the-Art Therapeutic Applications.318. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnstad PG (2018): Powerful substances in tiny amounts: An interview study of psychedelic microdosing. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 35:39–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nichols DE (2013): Serotonin, and the past and future of LSD. MAPS Bull. 23:20–23. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waldman A (2018): A really good day: how microdosing made a mega difference in my mood, my marriage, and my life. Anchor Books. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pollan M (2018): How to change your mind: what the new science of psychedelics teaches us about consciousness, dying, addiction, depression, and transcendence. Penguin. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polito V, Stevenson RJ (2019): A systematic study of microdosing psychedelics. PloS one. 14:e0211023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Celada P, Puig MV, Amargós-Bosch M, Adell A, Artigas F (2004): The therapeutic role of 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors in depression. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 29:252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Passie T, Halpern JH, Stichtenoth DO, Emrich HM, Hintzen A (2008): The pharmacology of lysergic acid diethylamide: a review. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 14:295–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Backstrom JR, Chang MS, Chu H, Niswender CM, Sanders-Bush E (1999): Agonist-directed signaling of serotonin 5-HT 2C receptors: Differences between serotonin and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). Neuropsychopharmacology. 21:77S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marona-Lewicka D, Thisted RA, Nichols DE (2005): Distinct temporal phases in the behavioral pharmacology of LSD: dopamine D 2 receptor-mediated effects in the rat and implications for psychosis. Psychopharmacology. 180:427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Preller KH, Herdener M, Pokorny T, Planzer A, Kraehenmann R, Stämpfli P, et al. (2017): The fabric of meaning and subjective effects in LSD-induced states depend on serotonin 2A receptor activation. Current Biology. 27:451–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Preller KH, Burt JB, Ji JL, Schleifer CH, Adkinson BD, Stampfli P, et al. (2018): Changes in global and thalamic brain connectivity in LSD-induced altered states of consciousness are attributable to the 5-HT2A receptor. Elife. 7:e35082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wacker D, Wang C, Katritch V, Han GW, Huang X-P, Vardy E, et al. (2013): Structural features for functional selectivity at serotonin receptors. Science. 340:615–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolder PC, Liechti ME, Rentsch KM (2015): Development and validation of a rapid turboflow LC-MS/MS method for the quantification of LSD and 2-oxo-3-hydroxy LSD in serum and urine samples of emergency toxicological cases. Analytical andbioanalytical chemistry. 407:1577–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savage C (1952): Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD-25) a clinical-psychological study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 108:896–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vollenweider FX, Kometer M (2010): The neurobiology of psychedelic drugs: implications for the treatment of mood disorders. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 11:642–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchborn T, Schröder H, Höllt V, Grecksch G (2014): Repeated lysergic acid diethylamide in an animal model of depression: Normalisation of learning behaviour and hippocampal serotonin 5-HT2 signalling. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 28:545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gasser P, Holstein D, Michel Y, Doblin R, Yazar-Klosinski B, Passie T, et al. (2014): Safety and efficacy of lysergic acid diethylamide-assisted psychotherapy for anxiety associated with life-threatening diseases. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 202:513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krebs TS, Johansen P-Ø (2012): Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) for alcoholism: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 26:994–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carhart-Harris RL, Kaelen M, Bolstridge M, Williams T, Williams L, Underwood R, et al. (2016): The paradoxical psychological effects of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). Psychological medicine. 46:1379–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ona G (2018): Inside bad trips: Exploring extra-pharmacological factors. Journal of Psychedelic Studies. 2:53–60. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Müller F, Lenz C, Dolder P, Lang U, Schmidt A, Liechti M, et al. (2017): Increased thalamic resting-state connectivity as a core driver of LSD-induced hallucinations. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 136:648–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt A, Müller F, Lenz C, Dolder P, Schmid Y, Zanchi D, et al. (2018): Acute LSD effects on response inhibition neural networks. Psychological medicine. 48:1464–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Müller F, Dolder PC, Schmidt A, Liechti ME, Borgwardt S (2018): Altered network hub connectivity after acute LSD administration. NeuroImage: Clinical. 18:694–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dolder PC, Schmid Y, Müller F, Borgwardt S, Liechti ME (2016): LSD acutely impairs fear recognition and enhances emotional empathy and sociality. Neuropsychopharmacology. 41:2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaelen M, Barrett FS, Roseman L, Lorenz R, Family N, Bolstridge M, et al. (2015): LSD enhances the emotional response to music. Psychopharmacology. 232:3607–3614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harvey JA (2003): Role of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor in learning. Learning & Memory. 10:355–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romano AG, Quinn JL, Li L, Dave KD, Schindler EA, Aloyo VJ, et al. (2010): Intrahippocampal LSD accelerates learning and desensitizes the 5-HT 2A receptor in the rabbit, Romano et alet al. Psychopharmacology. 212:441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ly C, Greb AC, Cameron LP, Wong JM, Barragan EV, Wilson PC, et al. (2018): Psychedelics promote structural and functional neural plasticity. Cell reports. 23:3170–3182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yanakieva S, Polychroni N, Family N, Williams Lt, Luke DP, Terhune DB (2018): The effects of microdose LSD on time perception: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Psychopharmacology. 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prochazkova L, Lippelt DP, Colzato LS, Kuchar M, Sjoerds Z, Hommel B (2018): Exploring the effect of microdosing psychedelics on creativity in an open-label natural setting. Psychopharmacology. 235:3401–3413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dolder PC, Schmid Y, Haschke M, Rentsch KM, Liechti ME (2015): Pharmacokinetics and concentration-effect relationship of oral LSD in humans. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology.pyv072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morean ME, de Wit H, King AC, Sofuoglu M, Rueger SY, O’Malley SS (2013): The drug effects questionnaire: psychometric support across three drug types. Psychopharmacology. 227:177–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin W, Sloan J, Sapira J, Jasinski D (1971): Physiologic, subjective, and behavioral effects of amphetamine, methamphetamine, ephedrine, phenmetrazine, and methylphenidate in man. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 12:245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McNair D, Lorr M, Droppleman L (1971): POMS, Profile of mood states. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Services. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dittrich A (1998): The standardized psychometric assessment of altered states of consciousness (ASCs) in humans. Pharmacopsychiatry. 31:80–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jaeggi SM, Buschkuehl M, Jonides J, Perrig WJ (2008): Improving fluid intelligence with training on working memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105:6829–6833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams KD, Jarvis B (2006): Cyberball: A program for use in research on interpersonal ostracism and acceptance. Behavior research methods. 38:174–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN (1999): International affective picture system (IAPS): Technical manual and affective ratings. Gainesville, FL: The Center for Research in Psychophysiology, University of Florida. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larsen JT, Norris CJ, McGraw AP, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT (2009): The evaluative space grid: A single-item measure of positivity and negativity. Cognition and Emotion. 23:453–480. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mednick SA (1968): The remote associates test. The Journal of Creative Behavior. 2:213–214. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liechti ME, Dolder PC, Schmid Y (2017): Alterations of consciousness and mystical-type experiences after acute LSD in humans. Psychopharmacology. 234:1499–1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.dos Santos RG, Osorio FL, Crippa JAS, Riba J, Zuardi AW, Hallak JE (2016): Antidepressive, anxiolytic, and antiaddictive effects of ayahuasca, psilocybin and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD): a systematic review of clinical trials published in the last 25 years. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 6:193–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horsley RR, Palenicek T, Kolin J, Vales K (2018): Psilocin and ketamine microdosing: effects of subchronic intermittent microdoses in the elevated plus-maze in male Wistar rats. Behavioural pharmacology. 29:530–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cameron LP, Benson CJ, DeFelice BC, Fiehn O, Olson DE (2019): Chronic, Intermittent Microdoses of the Psychedelic N, N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT) Produce Positive Effects on Mood and Anxiety in Rodents. ACS chemical neuroscience. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kraehenmann R, Pokorny D, Vollenweider L, Preller KH, Pokorny T, Seifritz E, et al. (2017): Dreamlike effects of LSD on waking imagery in humans depend on serotonin 2A receptor activation. Psychopharmacology. 234:2031–2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mueller F, Lenz C, Dolder P, Harder S, Schmid Y, Lang U, et al. (2017): Acute effects of LSD on amygdala activity during processing of fearful stimuli in healthy subjects. Translational psychiatry. 7:e1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Preller KH, Pokorny T, Hock A, Kraehenmann R, Stämpfli P, Seifritz E, et al. (2016): Effects of serotonin 2A/1A receptor stimulation on social exclusion processing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113:5119–5124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tagliazucchi E, Roseman L, Kaelen M, Orban C, Muthukumaraswamy SD, Murphy K, et al. (2016): Increased global functional connectivity correlates with LSD-induced ego dissolution. Current Biology. 26:1043–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anderson T, Petranker R, Rosenbaum D, Weissman CR, Dinh-Williams L-A, Hui K, et al. (2019): Microdosing Psychedelics: Personality, mental health, and creativity differences in microdosers. Psychopharmacology. 236:731–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.