Abstract

Tumor mitochondria have heightened protein folding quality control, but the regulators of this process and how they impact cancer traits are not completely understood. Here we show that the ATP-directed mitochondrial protease, LonP1 is upregulated by stress conditions, including hypoxia, in tumor, but not normal cells. In mitochondria, LonP1 is phosphorylated by Akt on Ser173 and Ser181, enhancing its protease activity. Interference with this pathway induces accumulation of misfolded subunits of electron transport chain complex II and complex V, resulting in impaired oxidative bioenergetics and heightened ROS production. Functionally, this suppresses mitochondrial trafficking to the cortical cytoskeleton, shuts off tumor cell migration and invasion, and inhibits primary and metastatic tumor growth, in vivo. These data identify LonP1 as a key effector of mitochondrial reprogramming in cancer and potential therapeutic target.

Keywords: Mitochondria, LonP1, protease, hypoxia, Akt, tumor growth, metastasis

INTRODUCTION

The control of protein homeostasis, or proteostasis is essential for cellular adaptation to disparate environmental cues [1]. This process is important for the integrity of subcellular organelles, in particular the endoplasmic reticulum [2] and mitochondria [3], and relies on protein (re)folding by molecular chaperones [4], or, conversely, proteolytic removal of aggregated or misfolded proteins [5]. Defective proteostasis can irreversibly impair organelle functions [6], and activate cell death through an unfolded protein response (UPR) [7].

Although tumors tend to shift their metabolism towards glycolysis even when oxygen is present [8], there has been resurgent interest in the role of mitochondria in cancer [9]. How mitochondrial biology engenders malignant behavior is only beginning to emerge [10], but there is evidence that heightened protein folding quality control is a common trait of tumor mitochondria [11]. Maintained by molecular chaperones, such as the Heat Shock Protein-90 (Hsp90) homolog, TNFR-Associated Protein-1 (TRAP1) [11] and ClpXP proteases [12], mitochondrial proteostasis buffers the risk of proteotoxic stress [13], dampens aberrant ROS production [14, 15], opposes cell death [16] and sustains bioenergetics [17].

Among the effectors of mitochondrial proteostasis [18] is the evolutionarily-conserved, ATP-dependent protease, LonP1 [19]. Similar to other mediators of protein folding quality control, LonP1 is exploited in cancer [20, 21], modulating cell death [22], ROS levels [23] and metabolic reprogramming [24] to promote primary and metastatic tumor growth. As a downstream target gene of HIF-1 [25], LonP1 may orchestrate proteostasis under stress conditions [20], including the tumor response to hypoxia [26]. On the other hand, the regulators of LonP1 activity have not been identified and how this pathway affects mitochondrial functions has remained controversial, variously associated with oxidative or glycolytic metabolism [27], and assembly or disassembly of disparate electron transport chain (ETC) complexes [23, 24].

In this study, we investigated the mechanisms of stress-regulated LonP1 proteostasis in tumor mitochondria and their implications for advanced cancer traits.

RESULTS

Stress-regulated LonP1 expression in tumor mitochondria

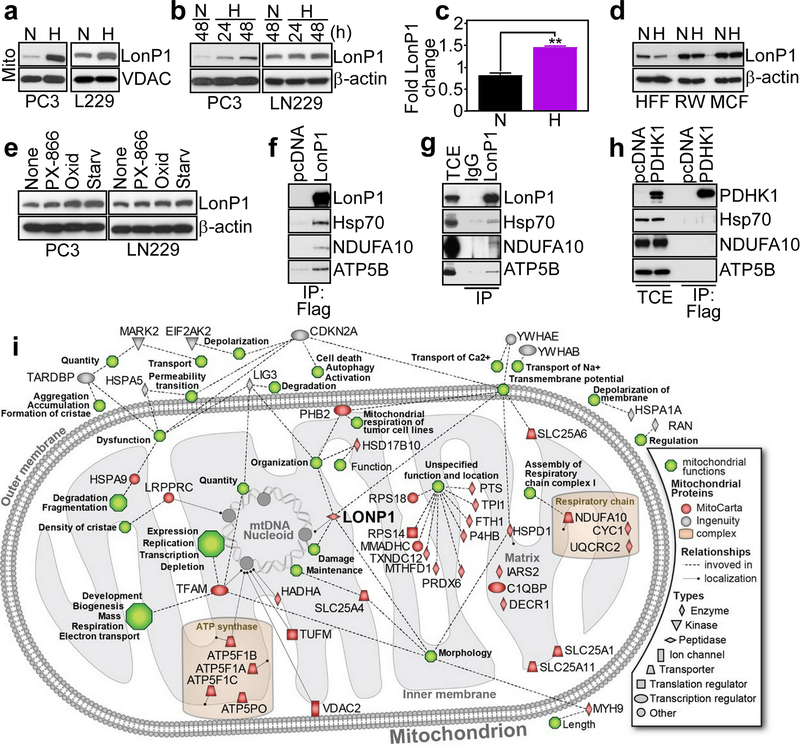

We began this study by examining a potential stress-regulated modulation of LonP1 in cancer. We found that exposure of prostate adenocarcinoma PC3 or glioblastoma LN229 cells to hypoxia (1% O2 for 48 h) increased LonP1 levels in isolated mitochondria (Fig. 1a) throughout a 48-h time interval (Fig. 1b). This was associated with increased LonP1 mRNA expression in hypoxia, compared to normoxic cultures (Fig. 1c). Conversely, hypoxia did not modulate LonP1 levels in normal cells, including human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF), prostate epithelial RWPE1 (RW) or breast epithelial MCF10A (MCF) cells (Fig. 1d). In addition to hypoxia, exposure of tumor cells to stress stimuli such as small molecule PI3 kinase inhibitor, PX-866, oxidative stress (H2O2), or serum starvation also increased LonP1 levels (Fig. 1e).

Fig. 1.

Stress-regulated mitochondrial LonP1 proteome. a and b PC3 or LN229 cells in normoxia (N) or hypoxia (H, 1% O2) were analyzed after the indicated time intervals by Western blotting. c The conditions are as in a and changes in LonP1 mRNA levels were quantified by qPCR. Mean±SD of replicates (n=2). **, p=0.003. d The conditions are as in a and normal HFF, RWPE1 (RW) or MCF10A (MCF) cells were analyzed by Western blotting. e PC3 or LN229 cells were exposed to small molecule PI3K inhibitor, PX-866, oxidative stress (Oxid, H2O2) or serum starvation (Starv) for 48 h and analyzed by Western blotting. f PC3 cells transfected with Flag-pcDNA or Flag-LonP1 were immunoprecipitated (IP) with an antibody to Flag and analyzed by Western blotting. g PC3 cells were IP with non-binding IgG or an antibody to LonP1 and analyzed by Western blotting. TCE, total cell extracts. h PC3 cells were transfected with Flag-pcDNA or Flag-PDHK1, IP with an antibody to Flag and analyzed by Western blotting. i Functional and localization annotation of LonP1-associated mitochondrial proteome in PC3 cells. Proteins are identified by different shapes denoting their cellular roles based on Ingenuity Knowledgebase information. Red colors correspond to mitochondrial proteins recorded in MitoCarta 2 database. Dotted lines indicate protein involvement in mitochondrial functions (green hexagons) according to Ingenuity Knowledgebase. Solid lines or positions within the mitochondrial inner or outer membrane, matrix or mtDNA nucleoid indicate protein localization according to Gene Ontology information. Known mitochondrial protein complexes are highlighted.

To understand how LonP1 may affect mitochondrial functions, we next carried out a proteomics screening of LonP1-associated molecules in PC3 cells (Supplementary Figure S1). In these experiments, we identified a mitochondrial LonP1-interactome that comprises subunits of ETC complex I (NDUFA10), complex III (cytochrome c1) and complex V (ATP5F1A, ATP5F1B, ATP5F1C, ATP5PO), transcriptional regulator (TFAM), effectors of protein folding (HspA9/Hsp70, HspA5/Grp78) and mitochondrial solute carrier proteins (SLC25A11, SLC25A1, SLC25A6) (Supplementary Figure S1). Consistent with these results, immune complexes of Flag-LonP1 (Fig. 1f) or endogenous LonP1 (Fig. 1g) precipitated from PC3 cells contained co-associated Hsp70, NDUFA10 and ATP5B. In contrast, immune complexes of Flag-Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase-1 (PDHK1), another mitochondrial regulator of the tumor response to hypoxia [26], did not contain LonP1-interacting proteins (Fig. 1h). Finally, Ingenuity Pathway analysis of proteomics data connected LonP1 to key mechanisms of mitochondrial function, including oxidative phosphorylation, assembly of ETC complex(es) and organelle dynamics (Fig. 1i).

LonP1 regulation of mitochondrial protein folding

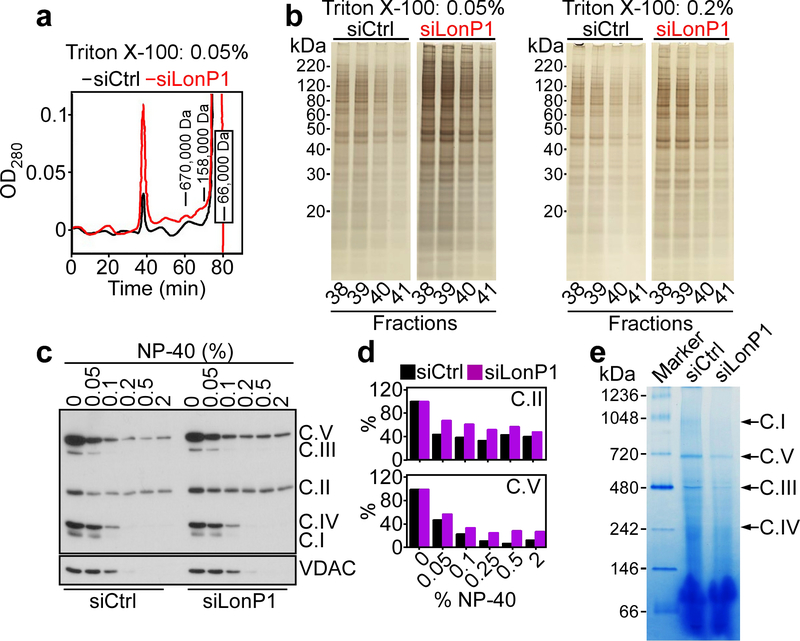

To explore the function of LonP1, we next characterized siRNA (Supplementary Figure S2A) or shRNA (Supplementary Figure S2B) sequences that silence LonP1 expression in tumor cells. Fist, HPLC gel filtration fractionation of mitochondrial extracts from PC3 cells demonstrated that LonP1 knockdown induced the accumulation of very high molecular weight protein aggregates that eluted in the void volume of a gel filtration column (complexes with apparent solution hydrodynamic size >5 million Da), compared to control transfectants (Fig. 2a). SDS gel electrophoresis and silver staining of HPLC void volume fractions showed that aggregated proteins were more abundant at low (0.05%) and intermediate (0.2%) detergent (Triton X-100) concentrations after LonP1 silencing (Fig. 2b). This difference was less apparent at higher detergent concentrations (2%) after LonP1 knockdown, compared to control siRNA (Supplementary Figure S2C) indicating that the high detergent concentration could disperse the very large protein aggregates. Consistent with these findings, LonP1 knockdown in PC3 cells resulted in the accumulation of detergent insoluble, i.e. misfolded subunits of ETC complex V (ATP5A) and complex II (SDHB), compared to control transfectants (Fig. 2c and d). Complex II subunit SDHA (Supplementary Figure S2D and E) and complex V subunit ATP5B (Supplementary Figure S2F and G) also became misfolded after LonP1 loss. In contrast, other subunits of complex II (SDHC, SDHD), complex III (UQCRC2), complex I (NDUFB8), complex IV (Cox-II) or VDAC were not affected (Figure 2c, Supplementary Figure S2D and E). To independently complement these observations, we next looked at the integrity of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complex(es) in control or LonP1 knockdown cells by native blue gel analysis. In these experiments, siRNA silencing of LonP1 significantly reduced the assembly of mitochondrial complex I, V, III and IV, compared control siRNA transfectants (Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2.

Regulation of mitochondrial protein folding by LonP1. a Mitochondrial extracts of PC3 cells transfected with control non-targeting siRNA (siCtrl) or LonP1-directed siRNA (siLonP1) were prepared and replicate aliquots were solubilized in 0.05%, 0.2% or 2% Triton X-100 followed by fractionation using HPLC gel filtration. Chromatogram of the 0.05% extract. The positions of molecular weight standards are indicated. The void volume (>5 million Da) is the peak centered at 39 minutes. b The conditions are as in a, and the indicated HPLC void volume fractions were analyzed by SDS gel electrophoresis followed by silver staining. The detergent concentrations per each condition are indicated. Representative experiment. c and d PC3 cells were transfected with siCtrl or siLonP1 and detergent (NP-40)-insoluble proteins were analyzed by Western blotting (c) and quantified by densitometry (d). C, mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complex. Representative experiment (n=2). e Mitochondrial extracts from PC3 cells transfected with siCtrl or siLonP1 were solubilized in 1% digitonin and analyzed by native blue gel electrophoresis. The position of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complexes is indicated. Marker, molecular weight markers.

LonP1-directed proteostasis is required for mitochondrial bioenergetics

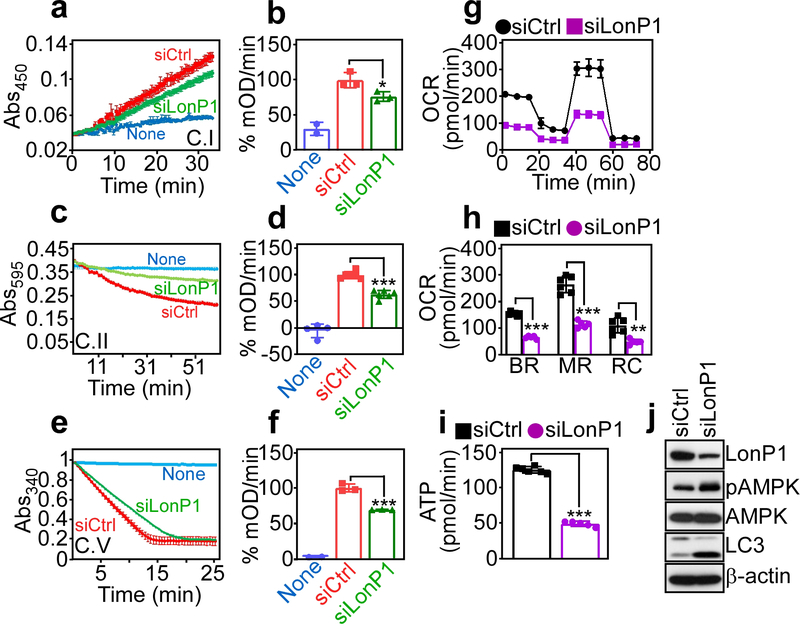

Based on these findings, we next asked if protein misfolding after LonP1 loss affected mitochondrial bioenergetics. We found that siRNA silencing of LonP1 inhibited citrate synthase-normalized complex I (Fig. 3a and b), complex II (Fig. 3c and d) and complex V (Fig. 3e and f) activity in PC3 cells, compared to control siRNA transfectants. As a result, LonP1 knockdown cells exhibited lower oxygen consumption rates (OCR) (Fig. 3g) with decrease in both basal and maximal respiration, as well as spare respiratory capacity (Fig. 3h), and overall reduced ATP production (Fig. 3i). In line with impaired bioenergetics, targeted cells expressed markers of nutrient deprivation, including increased phosphorylation of the energy sensor, AMPK (Thr172) and heightened LC3 lipidation (Fig. 3j), suggestive of autophagy.

Fig. 3.

LonP1 regulation of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complex activity. a and b PC3 cells were transfected with siCtrl or siLonP1 and citrate synthase-normalized complex (C) I activity (a) was quantified (b). Mean±SD (n=3) *, p=0.03. c and d The conditions are as in a and complex II activity (c) was quantified (d). Mean±SD (n=6). ***, p=0.0006. e and f The conditions are as in a and complex V activity (e) was quantified (f). Mean±SD (n=3). ***, p<0.0001. g PC3 cells transfected with siCtrl or siLonP1 were analyzed for oxygen consumption rates (OCR) on a Seahorse XFe96 Bioenergetics Flux Analyzer. Representative tracings (n=3). h The conditions are as in g, and basal respiration (BR), maximal respiration (MR) or spare respiratory capacity (RC) was quantified per each condition. Mean±SD (n=5–6). ***, p<0.0001; **, p=0.001. i The conditions are as in g and transfected PC3 cells were analyzed for ATP production. Mean±SD (n=6–7). ***, p<0.0001. j PC3 cells transfected with the indicated siRNA were analyzed by Western blotting. p, phosphorylated.

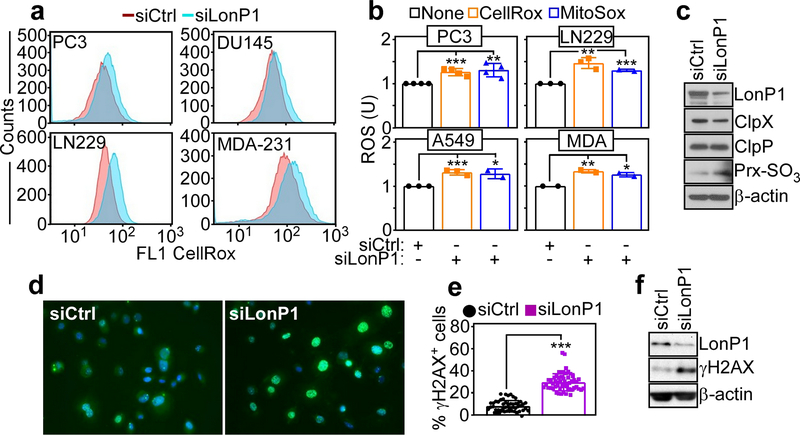

Consistent with a defective ETC, LonP1 silencing in multiple tumor cell types resulted in increased production of total ROS (Fig. 4a) as well as mitochondrial-derived ROS (Fig. 4b), compared to control transfectants. In addition, LonP1 knockdown was accompanied by hyperoxidation of Prx3, a marker of oxidative damage (Fig. 4c), and extensive γH2AX fluorescence reactivity (Fig. 4d and e), suggestive of a DNA damage response. Heightened γH2AX protein levels after LonP1 knockdown were also demonstrated by Western blotting (Fig. 4f). In contrast, other mitochondrial proteases previously implicated in ROS buffering, including ClpP or ClpX [14, 15] were not modulated before or after LonP1 silencing (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

LonP1 regulation of mitochondrial oxidative stress. a The indicated tumor cell lines transfected with siCtrl or siLonP1 were analyzed for total ROS production, by CellRox fluorescence staining and flow cytometry. Representative profiles (n=3). b The conditions are as in a and tumor cell types were quantified for cellular (CellRox) or mitochondrial (MitoSox) ROS production by flow cytometry. Mean±SD. The statistical analysis is as follows: PC3 (CellRox) ***, p=0.0007 (MitoSox) **, p=0.006; LN229 (CellRox) **, p=0.003 (MitoSox) ***, p=0.0001; A549 (CellRox) ***, p=0.0009 (MitoSox) *, p=0.01; MDA-231 (MDA) (CellRox) **, p=0.006 (MitoSox) *, p=0.01. U, units. c PC3 cells transfected as in a were analyzed by Western blotting. d and e PC3 cells transfected with the indicated siRNA were analyzed for γH2AX reactivity by fluorescence microscopy (d) and quantified (e). Each symbol corresponds to an individual determination (n=51–55). ***, p<0.0001. f PC3 cells transfected with the indicated siRNA were analyzed by Western blotting.

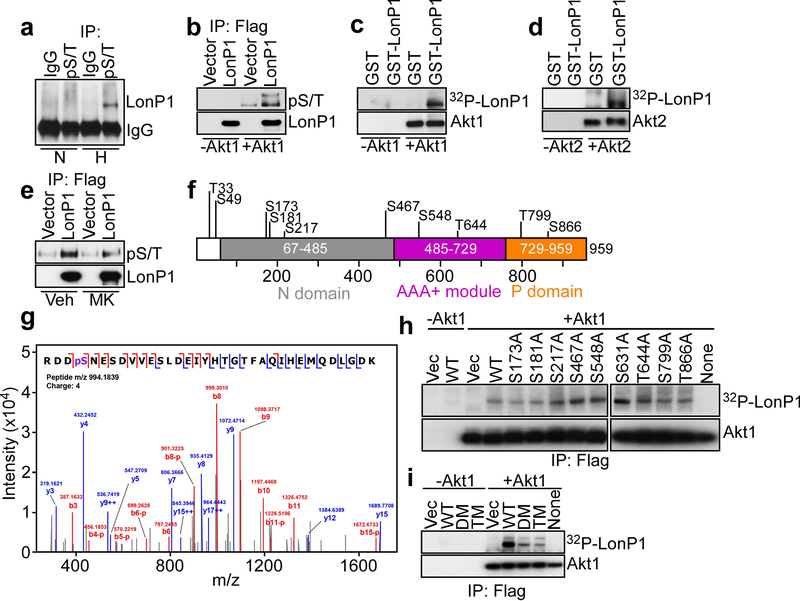

Akt1 phosphorylation in mitochondria regulates LonP1 activity

Recent studies have shown that hypoxia induces Akt accumulation in mitochondria, which contributes to tumor metabolic reprogramming [26]. Here, we found that LonP1 could be immunoprecipitated from PC3 cells exposed to hypoxia using an antibody to the Akt consensus phosphorylation sequence, ArgXXSer*/Thr* (pS/T, Fig. 5a, * phosphorylation site(s)). In contrast, LonP1 was not immunoprecipitated by the Akt pS/T antibody from normoxic cultures (Fig. 5a). To test the possibility that Akt phosphorylates LonP1, we next set up kinase assays with Flag-immunoprecipitated LonP1 in the presence or absence of recombinant Akt1 and unlabeled ATP. In these experiments, addition of Akt1 resulted in increased phosphorylation of LonP1, as detected by the Akt pS/T antibody (Fig. 5b). In contrast, no pS/T-reactive bands were detected in LonP1 immunoprecipitates in the absence of Akt1 (Fig. 5b). As an independent approach, we next expressed recombinant GST or GST-LonP1 and analyzed protein phosphorylation in a cell-free system in the presence of 32P-γATP. Here, a 32P-radiolabeled LonP1 band was readily detected in the presence, but not in the absence of Akt1 (Fig. 5c). Recombinant GST was not phosphorylated (Fig. 5c). We next asked if other Akt isoforms participated in this response, and we found that Akt2 also phosphorylated GST-LonP1, but not GST in a kinase assay with 32P-γATP (Fig. 5d). Finally, treatment of PC3 cells with a small molecule Akt inhibitor, MK2206 reduced the reactivity of immunoprecipitated LonP1 with the Akt pS/T antibody, compared to vehicle-treated cultures (Fig. 5e).

Fig. 5.

Akt phosphorylation of LonP1. a Mitochondrial extracts from PC3 cells maintained in normoxia (N) or hypoxia (H, 1% O2 for 48 h) were immunoprecipitated with control IgG or an antibody to Akt consensus phosphorylation site (RXXS/T, pS/T) followed by Western blotting. b PC3 cells transfected with Flag-vector or Flag-LonP1 were immunoprecipitated (IP) with an antibody to Flag and Flag-eluted proteins were mixed with (+) or without (−) recombinant Akt1 in the presence of unlabeled ATP and analyzed with an antibody to pS/T, by Western blotting. c and d Recombinant GST or GST-LonP1 was incubated with 32P-γATP in a kinase assay in the presence or absence of Akt1 (c) or Akt2 (d) and analyzed by autoradiography. e PC3 cells transfected with Flag-vector or Flag-LonP1 were treated with vehicle (Veh) or small molecule Akt inhibitor, MK2206 (MK), immunoprecipitated (IP) with an antibody to Flag and analyzed with an antibody to pS/T, by Western blotting. f Schematic diagram of predicted phosphorylation sites in LonP1. The individual N, AAA+ and P domains are indicated. g The conditions are as in b and Flag-eluted recombinant LonP1 was analyzed for phosphorylation-associated changes by mass spectrometry. A representative MS/MS spectrum of phosphorylated Ser173 peptide is shown. h The indicated Flag-eluted wild type (WT) LonP1 or individual Ala-substituted LonP1 mutant was immunoprecipitated (IP) from PC3 cells, mixed with 32P-γATP in a kinase assay in the presence or absence of Akt1 followed by autoradiography. i The conditions are as in b and Flag-eluted WT LonP1, double mutant (DM) LonP1 Ser173Ala/Ser181Ala or triple mutant (TM) LonP1 Ser173Ala/Ser181Ala/Ser799Ala immunoprecipitated (IP) from PC3 cells was mixed with 32P-γATP in a kinase assay in the presence or absence of Akt1 followed by autoradiography.

Inspection of the LonP1 primary sequence suggested the presence of multiple Ser/Thr phosphorylation sites (Fig. 5f, Supplementary Figure S3A), matching, at least in part, the consensus phosphorylation sequence for Akt (Supplementary Figure S3B). To identify LonP1 phosphorylation site(s), in vivo, we then examined Flag-vector or Flag-LonP1 immunoprecipitated from PC3 cells by mass spectrometry. In these experiments, Ser173 was identified as a novel phosphorylation site on LonP1, in vivo (Fig. 5g). To validate these results, and potentially identify other low-level phosphorylation sites undetected by proteomics, we next mutated to Ala all putative Akt phosphorylation sites in LonP1 (Supplementary Figure S3A). Consistent with the proteomics data, a LonP1 Ser173Ala mutant exhibited significantly reduced phosphorylation compared to wild type (WT) LonP1 in a kinase assay with Akt1 and 32P-γATP (Fig. 5h). In addition, LonP1 mutants Ser181Ala and Thr799Ala also exhibited decreased 32P-γATP incorporation in the presence of Akt1 (Fig. 5h). Immunoprecipitated Flag-vector was not phosphorylated and no 32P-γATP-labeled bands were detected in the absence of Akt1 (Fig. 5h). Based on these results, we next generated a double LonP1 mutant Ser173Ala/Ser181Ala (DM) or triple mutant Ser173Ala/Ser181Ala/Ser799Ala (TM) and analyzed their phosphorylation status. Compared to WT LonP1, Akt1 phosphorylation of immunoprecipitated LonP1 DM was significantly reduced in a kinase assay with 32P-γATP (Fig. 5i). In contrast, mutagenesis of Thr799Ala in LonP1 TM did not further decrease Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 5i), and no 32P-γATP-phosphorylated bands were detected in the absence of Akt1 (Fig. 5i). Based on these data, LonP1 DM was utilized in subsequent functional studies.

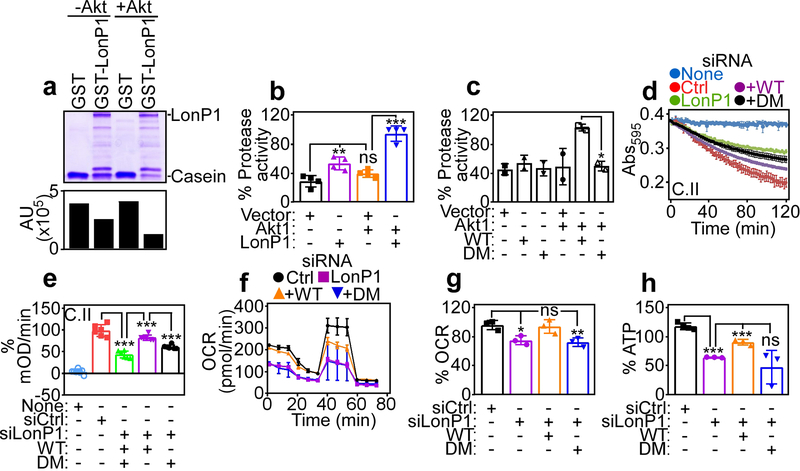

Akt1 phosphorylation regulates LonP1 protease activity and mitochondrial bioenergetics

To test whether Akt phosphorylation affected LonP1 protease activity, we next set up a cell-free caseinolytic assay with recombinant proteins. In these experiments, GST-LonP1 induced proteolytic degradation of casein by Coomassie blue staining of incubation reactions (Fig. 6a). However, addition of Akt and ATP in these settings significantly increased casein proteolysis by GST-LonP1 (Fig. 6a). Recombinant GST had no activity in the presence or absence of Akt (Fig. 6a). To independently validate these findings, we next assessed the proteolytic activity of Flag-vector or Flag-LonP1 immunoprecipitated from PC3 cells against a fluorogenic substrate. Although LonP1 exhibited proteolytic activity, compared to Flag-vector, inclusion of Akt1 and ATP considerably enhanced LonP1-directed proteolysis in this assay (Fig. 6b). Control vector had no proteolytic activity (Fig. 6b). In addition, immunoprecipitated phosphorylation-defective LonP1 DM exhibited no proteolytic activity in the presence or absence of Akt1 (Fig. 6c). Consistent with a stress-regulated response, exposure of PC3 cells to hypoxia also increased LonP1 proteolytic activity in a fluorogenic assay, compared to normoxic cultures (Supplementary Figure S3C).

Fig. 6.

Akt regulation of LonP1 protease activity and mitochondrial bioenergetics. a Recombinant GST or GST-LonP1 was incubated with or without Akt1 plus ATP and analyzed for proteolytic processing of casein by SDS gel electrophoresis and Coomassie blue staining. Bar graph, densitometric quantification of casein bands. b PC3 cells transfected with Flag-vector or Flag-LonP1 were immunoprecipitated with an antibody to Flag and Flag peptide-eluted proteins were analyzed for LonP1 proteolytic activity with or without Akt1 in a fluorogenic assay. Mean±SD (n=4). **, p=0.005; ***, p<0.0001; ns, not significant. c The conditions are as in b and Flag-eluted WT or LonP1 DM protein was analyzed for proteolytic activity with or without Akt1. Mean±SD (n=2). *, p=0.01. d and e PC3 cells transfected with siCtrl or siLonP1 were reconstituted with WT or DM LonP1 cDNA and citrate synthase-normalized complex (C) II activity (c) was quantified (d). Mean±SD (n=6–8). ***, p<0.0001. f and g The conditions are as in d and reconstituted PC3 cells were analyzed for OCR (f) and quantified (g). Mean±SD (n=3–4). *, p=0.01; **, p=0.009; ns, not significant. h The conditions are as in d and reconstituted PC3 cells were analyzed for ATP production. Mean±SD (n=3). ***, p=0.0008 - <0.0001; ns, not significant.

Next, we asked if phosphorylation-regulated LonP1 proteostasis was important for mitochondrial bioenergetics, and we reconstituted PC3 cells stably silenced for endogenous LonP1 with WT LonP1 or phosphorylation-defective LonP1 DM (Supplementary Figure S3D). Re-expression of WT LonP1 in these settings restored mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complex II activity (Fig. 6d and e), OCR (Fig. 6f and g), including basal and maximal respiration (Supplementary Figure S3E) and ATP production (Fig. 6h). In contrast, reconstitution with LonP1 DM did not correct the defects in complex II activity (Fig. 6d and e), mitochondrial respiration (Fig. 6f and g, Supplementary Figure S3E) or ATP production (Fig. 6h) in these settings. Furthermore, re-expression of WT, but not LonP1 DM corrected a potential compensatory increase in glucose consumption (Supplementary Figure S3F) and lactate production (Supplementary Figure S3G) in LonP1-silenced cells (Supplementary Figure S3F and G).

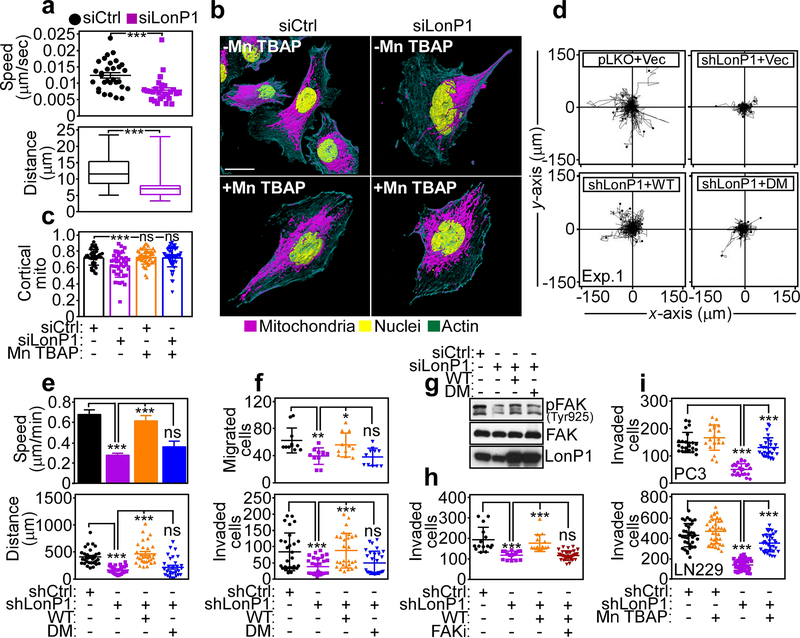

LonP1 regulation of mitochondrial trafficking and tumor cell motility

Mitochondrial metabolism is required for organelle dynamics, including subcellular trafficking to the cortical cytoskeleton, and a requirement of LonP1-directed bioenergetics in this response was next investigated. LonP1 silencing by siRNA blocked the subcellular trafficking of mitochondria in PC3 cells, by time-lapse videomicroscopy (Supplementary Figure S4A), suppressing both the speed of mitochondrial movements (Fig. 7a, top) as well as the total distance traveled by individual mitochondria, compared to control transfectants (Fig. 7a, bottom). As a result, mitochondria in LonP1 knockdown cells remained clustered in the perinuclear area and did not localize to the cortical cytoskeleton, as observed in control cultures (Fig. 7b and c). We speculated that toxic levels of ROS produced after LonP1 silencing inhibited mitochondrial trafficking. Consistent with this possibility, exposure of PC3 cells to the ROS scavenger, Mn TBAP inhibited total and mitochondrial ROS production after LonP1 knockdown (not shown) and restored mitochondrial accumulation at the cortical cytoskeleton in LonP1-silenced cells, quantitatively comparably to control transfectants (Fig. 7b and c).

Fig. 7.

LonP1 regulation of tumor cell motility and invasion. a PC3 cells transfected with siCtrl or siLonP1 were imaged for mitochondrial motility by time-lapse videomicroscopy and the speed of mitochondrial movements (top) and total distance traveled by individual mitochondria (bottom) was quantified (n=27–30). ***, p=0.0002. b and c The conditions are as in a and transfected PC3 cells were analyzed for subcellular mitochondrial accumulation at the cortical cytoskeleton with or without the ROS scavenger, Mn TBAP, by confocal fluorescence microscopy (b, 3D rendering of representative images) and quantified (c). siCtrl, n=22; siCtrl+Mn TBAP, n=19; siLonP1, n=22; siLonP1+Mn TBAP, n=23. ***, p<0.0001; ns, not significant. d PC3 cells stably transduced with pLKO or LonP1-directed shRNA were reconstituted with vector, WT or DM LonP1 cDNA and analyzed for cellular chemotaxis in 2D contour plots. Each tracing corresponds to an individual cell. Representative experiment (n=2). e The reconstitution conditions are as in d and the speed of cell motility (top) and total distance traveled by individual cells (bottom) was quantified (n=30). ***, p<0.0001; ns, not significant. f PC3 cells transduced with pLKO or LonP1-directed shRNA were analyzed for cell migration (top, n=11) or invasion across Matrigel-coated inserts (bottom, n=28). For cell migration, *, p=0.01; **, p=0.002. For cell invasion, ***, p=0.0004 - <0.0001; ns, not significant. g PC3 cells transfected with siCtrl or siLonP1 were reconstituted as in d and analyzed by Western blotting. p, phosphorylated. h PC3 cells stably transduced with pLKO or LonP1-directed shRNA were reconstituted with WT or DM LonP1 cDNA and analyzed for Matrigel invasion with or without small molecule FAK inhibitor (FAKi, GSK2256098) (n=15–30). ***, p<0.0001; ns, not significant. i. PC3 (top) or LN229 (bottom) cells stably transduced with pLKO or LonP1-directed shRNA were analyzed for invasion across Matrigel-coated inserts (PC3, n=23–27; LN229, n=35–42) with or without the ROS scavenger, Mn TBAP. For all panels, ***, p<0.0001.

Mitochondrial trafficking to the cortical cytoskeleton fuels tumor cell motility [28], and this possibility was next investigated in the context of LonP1 signaling. We found that stable shRNA knockdown of LonP1 suppressed tumor chemotaxis in 2D contour plots (Supplementary Figure S4B, Fig. 7d), reducing the speed of cell movements (Fig. 7e, top) and the total distance traveled by individual cells (Fig. 7e, bottom). Reconstitution of these cells with WT LonP1 rescued the defect of tumor chemotaxis (Fig. 7d) and restored quantitative parameters of cell motility comparably to control transfectants (Fig. 7e). In contrast, reconstitution of LonP1-silenced cells with phosphorylation-defective LonP1 DM had no effect (Fig. 7d and e). Consistent with inhibition of chemotaxis, shRNA silencing of LonP1 suppressed both tumor cell migration (Fig. 7f, top) and invasion across Matrigel-coated inserts (Supplementary Figure S4C, Fig. 7f, bottom). This effect was specific because re-expression of WT LonP1, but not LonP1 DM restored both tumor cell migration and invasion in these settings (Fig. 7f). Biochemically, loss of LonP1 was associated with reduced phosphorylation of cell motility kinase, Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK, Tyr925), in a response restored by re-expression of WT, but not LonP1 DM (Fig. 7g). We next used a pharmacologic approach to complement these experiments, and we found that a small molecule FAK inhibitor (GSK2256098) reversed the increase in Matrigel invasion of PC3 cells reconstituted with WT LonP1 (Fig. 7h). Finally, ROS scavenging with Mn TBAP also restored tumor cell migration (Supplementary Figure S4D) and invasion (Fig. 7i) in LonP1-knockdown cells, quantitatively indistinguishably from control transfectants.

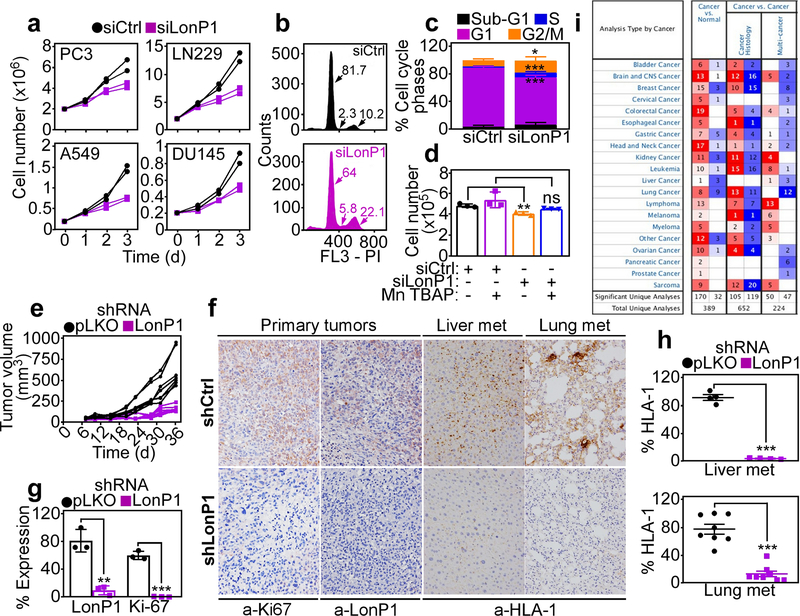

Modulation of tumor growth and metastasis by LonP1

Consistent with ROS-associated DNA damage, LonP1 knockdown cells exhibited reduced proliferation over a 3-d culture, in vitro (Fig. 8a). This was associated with sustained cell cycle arrest at G2/M and, to a lesser extent, S phase (Fig. 8b and c). In addition, exposure of LonP1-silenced cultures to further oxidative stress (H2O2) triggered cell death by apoptosis, as quantified by Annexin V staining and multiparametric flow cytometry (Supplementary Figure S5A). At comparable H2O2 concentrations, control PC3 transfectants exhibited minimal apoptotic cell death (Supplementary Figure S5A). Consistent with these results, ROS scavenging with Mn TBAP restored tumor cell proliferation under conditions of LonP1 depletion, quantitatively similar to control cultures (Fig. 8d).

Fig. 8.

Requirement of LonP1 for primary and metastatic tumor growth. a The indicated tumor cell types were transfected with siCtrl or siLonP1 and analyzed for cell proliferation over a 72-h time interval by direct cell counting. Each line corresponds to an individual experiment. b and c PC3 cells transfected as in a were analyzed by propidium iodide (PI) staining and flow cytometry (b) and the different cell cycle phases were quantified (c). Numbers correspond to the percentage of cells in each cell cycle phase. d PC3 cells transfected with siCtrl or siLonP1 were analyzed for cell proliferation after 72 h in the presence or absence of the ROS scavenger, Mn TBAP (n=3). **, p=0.004; ns, not significant. e PC3 cells transduced with pLKO or LonP1-directed shRNA were engrafted s.c. onto the flanks of immunocompromised athymic nude mice and tumor growth was measured with a caliper at the indicated time intervals. Each line corresponds to an individual tumor. f and g The conditions are as in e, and primary tumors from the indicated animal groups were stained with an antibody to LonP1 or Ki67 by immunohistochemistry (f) and quantified as percentage of expressing cells (g) (n=3). **, p=0.002; ***, p<0.0001. f and h Liver and lung samples harvested from the indicated animal groups as in e were stained with an antibody to HLA-1 by immunohistochemistry (f, representative images) and metastatic foci (met) were quantified (h). Each symbol (h) corresponds to an individual determination. Liver, n=4; ***, p<0.0001; lung, n=8; ***p<0.0001. i. Differential LonP1 gene expression in various tumor types compared to normal tissues based on Oncomine database. Numbers of independent studies showing significant (p<0.05) upregulation (red) or downregulation (blue) of LonP1 are indicated.

Finally, we looked at the impact of the LonP1 pathway on primary and metastatic tumor growth, in vivo. First, stable shRNA silencing of LonP1 nearly completely abolished xenograft (PC3) tumor growth in immunocompromised mice (Figure 8e). By comparison, control shRNA transfectants gave rise to exponentially growing tumors (Fig. 8e). By immunohistochemistry, LonP1-silenced tumors (Fig. 8f) had no expression of LonP1 and exhibited nearly complete loss of Ki67-positive cells, a marker of cell proliferation, compared to pLKO-transduced tumors (Fig. 8g). When analyzed for disease dissemination, LonP1 knockdown suppressed the formation of PC3 metastatic foci in liver and lungs, by immunohistochemistry of HLA-1 reactivity (Fig. 8f and h). Finally, and consistent with a broad exploitation of this pathway in cancer, bioinformatics analysis of the Oncomine gene expression database demonstrated that LonP1 was uniformly over-expressed in disparate malignancies compared to normal tissues, irrespective of histologic type or disease site (Fig. 8i). In addition, high levels of LonP1 correlated with shortened overall survival in patient cohorts of neuroblastoma, breast and colon adenocarcinoma and renal cell carcinoma (Supplementary Figure S5B).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have shown that Akt phosphorylation enhanes the protease activity of mitochondrial LonP1 under stress conditions, such as hypoxia. This is required to maintain protein quality control of multiple ETC complexes, including II and V subunits, preserve oxidative bioenergetics and dampen the production of toxic ROS. Interference with this pathway suppresses subcellular mitochondrial trafficking, shuts off tumor cell motility and inhibits primary and metastatic tumor growth, in vivo.

There is now considerable evidence that heightened protein folding quality control in mitochondria facilitates the acquisition of tumor traits important for disease progression [11]. Although LonP1 contributes to this “proteostasis network” [19] in cancer [20, 21], the mechanistic requirements of this pathway had not been clearly elucidated. Here, LonP1 regulation not only involved increased protein expression in response to stress stimuli, such as hypoxia [25], but also a novel phosphorylation step by mitochondria-localized Akt1 on Ser173 and Ser181 that enhanced its protease activity. The structural requirements of how phosphorylation on these sites regulates LonP1 protease function remain to be elucidated. However, given the position of Ser173 and Ser181 in the N domain of LonP1, it seems plausible that modification(s) on these residues may affect substrate binding [29] in anticipation of ATP hydrolysis for optimal proteolysis in the degradation chamber [30, 31].

Although the role of Akt signaling in tumor progression is well established [32], less is known about a pool of Akt recruited to mitochondria in cancer [33]. This was first implicated as an adaptive response to molecular therapy [34], where mitochondrial Akt phosphorylation of matrix cyclophilin D inhibited programmed cell death and promoted drug resistance [35]. Here, Ser173 and Ser181 on LonP1 matched only in part the consensus phosphorylation sequence for Akt, prompting the possibility that other kinase(s) may also target these residues. On the other hand, kinase assays with recombinant proteins, in vitro, combined with mutagenesis and reconstitution studies, in vivo, support an important role of mitochondrial Akt in enhancing LonP1 protease activity in cancer. Accordingly, independent studies have recently expanded the role of mitochondrial Akt in tumor responses, including phosphorylation of PDHK1 for metabolic reprogramming in hypoxia [26], modulation of mitochondrial Ca2+ transport via phosphorylation of the calcium uniporter MICU1 [36], and regulation of mitochondria-ER contact sites [37].

Previously, the role of LonP1 on ETC function had remained uncertain, as both overexpression or depletion of LonP1 lowered mitochondrial respiration and decreased the expression of multiple ETC subunits, including complex I, II and IV [24]. Instead, we have shown here that active LonP1 maintains protein quality control of selected ETC subunits, and that interference with this pathway triggers the accumulation of misfolded complex II- and V-associated proteins, and defective assembly of multiple ETC complexes in mitochondria. The biochemical requirements of mitochondrial respiration are well understood [38], but the possibility that ETC activity critically relies on protein folding, especially in cancer, is only recently beginning to emerge. For example, the iron-sulfur subunit of complex II, SDHB has been identified as a target of multiple proteostasis effectors in cancer, including TRAP1-directed protein (re)folding [17], proteolysis by ClpXP [15], and now LonP1 (this study). This suggests a unique vulnerability of complex II subunit(s) to proteotoxic stress, or, alternatively, more stringent requirements of protein folding for optimal complex II activity in tumor mitochondria.

One of the key consequences of LonP1 targeting was increased production of ROS, which in turn exerted anti-tumorigenic effects of inhibition of cell proliferation and suppression of cell motility [20, 21]. A role of LonP1 in buffering toxic ROS has been proposed earlier through proteolysis of oxidized proteins [39], but the data presented here suggest a more direct role of this pathway in maintaining the integrity of complex V, a critical site for mitochondrial ROS generation [38]. The role of ROS in cancer continues to be debated and likely reflects cell- and context-specific responses [40]. As signaling molecules, ROS may contribute to tumorigenesis via oncogene activation [41], whereas higher ROS levels have been associated with cytotoxicity and suppression of metastasis [42]. Along this line, increased ROS production after LonP1 silencing caused DNA damage, sustained G2/M cell cycle arrest and inhibition of mitochondrial trafficking to the cortical cytoskeleton. A component of mitochondrial dynamics, which regulates organelle shape, size and subcellular position [43], the redistribution of mitochondria to the cortical cytoskeleton [28] has been shown to provide a concentrated, “regional” energy source to fuel tumor cell motility [44], invasion and metastatic dissemination, in vivo [45, 46]. Consistent with this model, inhibition of mitochondrial dynamics after loss of LonP1 abolished tumor cell motility and suppressed primary and metastatic tumor growth, in vivo.

In sum, these results provide a mechanistic foundation for the exploitation of LonP1-directed proteostasis in mitochondrial reprogramming in cancer [20, 21]. The role of this pathway in ETC quality control, oxidative bioenergetics, ROS production and mitochondrial dynamics fits well with the observed upregulation of LonP1 in genetically disparate tumors, and association with shorter overall patient survival (this study). Conversely, proof-of-concept studies have demonstrated that effector molecules in the mitochondrial “proteostasis network”, TRAP1 [11], ClpXP [14, 15], as well as LonP1 [20, 21] may provide actionable therapeutic targets, removing disparate mechanisms of mitochondrial adaptation exploited for disease progression and metastatic competence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The following materials and methods are described in the Supplementary Materials and Methods section that accompanies this paper:

Cells and cell culture

Antibodies and reagents

Plasmids and gene silencing

Protein analysis

Analysis of bioenergetics

Fluorescence microscopy

Oxidative phosphorylation

Native blue gel analysis

Mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) activity

Mitochondrial ROS quantification in live cells

Quantification of cortical mitochondria

Tumor cell motility

Tumor cell invasion

Immunohistochemistry

Mitochondria time-lapse videomicroscopy

Cells (2×104) growing on high optical-quality glass bottom 35-mm plates (MatTek Corporation) were incubated with 100 nM Mitotracker Deep Red FM dye for 1 h and imaged on a Leica TCS SP8 X inverted laser scanning confocal microscope using a 63X 1.40NA oil objective. Short duration time-lapse sequences were carried out using a Tokai Hit incubation chamber equilibrated to 37°C and 5% CO2 bidirectional scanning at 8000 Hz using a resonant scanner. Time lapse was performed for 1000 sec (10 sec per frame). Individual 12-bit images were acquired using a white-light supercontinuum laser (2% at 645 nm) and HyD detectors at 2X digital zoom with a pixel size of 90 nm x 90 nm. A pinhole setting of 1 Airy Units provided a section thickness of 0.896 μm. Each time point was captured as a stack of approximately 11 overlapping sections with a step size of 0.5 μm. At least 5 single cells per condition were collected for analysis. Initial post-processing of the 3D sequences was carried out with Leica LAS X software to create an iso-surface visualization. Images imported into Image J Fiji and individual mitochondria were manually tracked using the Manual Tracking plugin. Mitochondria (approximately 10 mitochondria per cell) were tracked along the stacks until a fusion event prevented continued tracking. The speed and distance for each time interval were used to calculate the mean speed and cumulative distance traveled by each individual mitochondrion.

Mitochondrial protein folding

Mitochondrial protein folding assays were performed as described [17]. Briefly, mitochondrial fractions were isolated from PC3 cells transfected with control non-targeting siRNA or LonP1-directed siRNA. Samples were suspended in equal volume of mitochondrial fractionation buffer (Fisher Scientific) containing increasing concentrations of NP-40 (0%, 0.05%, 0.1%, 0.2%, 0.5%, or 2.0%) for 25 min on ice with vortexing every 5 min. Detergent-insoluble protein aggregates were isolated by centrifugation at 20,000 g for 20 min, separated on SDS polyacrylamide gels and analyzed by Western blotting. For HPLC gel filtration experiments, mitochondrial fractions isolated from PC3 cells transfected with siCtrl or siLonP1 were resuspended in buffer as described above and containing 0.05%, 0.2% or 2% Triton X-100. For each sample, 200 μl was separated on 2 Superose 6 (GE Heathcare) gel filtration columns connected in series that were equilibrated in 25 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.4 and the corresponding concentration of Triton X-100 (i.e., 0.05%, 0.2% or 2%) at 4oC. One-minute fractions were collected and analyzed using 10% Bis-Tris SDS-PAGE gels (Invitrogen) followed by detection using SilverQuest Stain (Invitrogen).

LonP1 protease activity

Purified human LonP1 (1 μg) or Akt1-phosphorylated Lonp1 was incubated in a 100 μl reaction cocktail containing 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and 10 mM MgCl2 with or without 2.5 mM ATP for 5 min at 37°C. Then, FITC-casein substrate (2 μg) was added to initiate the proteolytic reaction for 1 h at 37°C. The release of FITC molecules as a result of LonP1 proteolysis was quantified continuously using a fluorescence detector with excitation set at 485 nm and emission 535 nm [47]. In another series of experiments, recombinant GST or GST-LonP1 was mixed with Akt1 and ATP, incubated with casein at 37°C and proteolysis was determined by Coomassie blue staining and densitometric quantification of casein bands.

Proteomics analysis

To identify LonP1-associated proteins in mitochondria, immunoprecipitates of Flag-LonP1 or Flag-vector were separated on an SDS-gel for approximately 5 mm followed by fixing and staining with colloidal Coomassie. The entire region of the gel-containing protein was excised and digested with trypsin. To identify Akt1 phosphorylation sites on LonP1, immunoprecipitates of Flag-LonP1 in the presence of Akt1 were fully separated by SDS-gel electrophoresis, stained with colloidal Coomassie, and the LonP1 protein band was excised and digested with trypsin. Tryptic peptides were analyzed by LC-MS/MS on a Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) coupled with a Nano-ACQUITY UPLC system (Waters). Samples were injected onto a UPLC Symmetry trap column (180 μm i.d. x 2 cm packed with 5 μm C18 resin; Waters), and tryptic peptides were separated by RP-HPLC on a BEH C18 nanocapillary analytical column (75 μm i.d. x 25 cm, 1.7 μm particle size; Waters) using a 90-min gradient. Eluted peptides were analyzed in data-dependent mode where the mass spectrometer obtained full MS scans from 400 to 2000 m/z at 60,000 resolution. Full scans were followed by MS/MS scans at 15,000 resolution on the 20 most abundant ions. Peptide match was set as preferred, the exclude isotopes option and charge-state screening were enabled to reject singly and unassigned charged ions. MS/MS spectra were searched using MaxQuant 1.6.1.0 [48] against the UniProt human protein database (October 2017). MS/MS spectra were searched using full tryptic specificity with up to two missed cleavages, static carboxamidomethylation of Cys, and variable oxidation of Met, protein N-terminal acetylation, and phosphorylation of Ser, Thr and Tyr. Consensus identification lists were generated with false discovery rates of 1% at protein, peptide and site levels. Protein quantitation and fold changes of Flag-LonP1 vs Flag-vector were determined from the iBAQ intensity. Missing values were replaced with a minimal value of 30,000. A total of 244 proteins with at least 2-fold enrichment were considered for further annotation analysis.

Association of enriched proteins with mitochondria was determined using Mitocarta 2.0 database [49], QIAGEN’s Ingenuity® Pathway Analysis software (IPA®, QIAGEN Redwood City, www.qiagen.com/ingenuity) and Gene Ontology categories related to mitochondrial components: GO:0005759 – matrix, GO:0005743 - inner membrane, GO:0005741 - outer membrane, GO:0042645 – nucleoid; and complexes: combined GO:0005747, GO:0045273, GO:0005750, GO:0005751 for respiratory chain complex, combined GO:0000275, GO:0005753, GO:0005754 for proton-transporting ATP synthase complex. All proteins found to be associated with mitochondrial functions and components based on at least one annotation source were combined and reported in a one single model.

Animal studies

Studies involving mice were carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of The Wistar Institute. PC3 cells stably transfected with pLKO or LonP1-directed shRNA were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) in athymic nude mice (2 tumors/mouse, 5 mice per group), and superficial tumor growth was quantified with a caliper over a five-week time interval from engraftment. For analysis of metastasis, lungs and liver were harvested from animals in the two groups and processed for immunohistochemistry.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean±SEM or mean±SD of multiple independent experiments or replicates of representative experiments out of a minimum of two or three independent determinations. Two-tailed Student’s t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for two-group comparative analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad software package (Prism 6.0) for Windows. A p value of ˂0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank James Hayden and Frederick Keeney for assistance with time-lapse videomicroscopy and Sandra Harper for performing the HPLC gel filtration experiments. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants P01 CA140043 (D.C.A., L.R.L. and D.W.S.), R35 CA220446 (D.C.A.) R50 CA221838 (H.-Y.T) and R50 CA211199 (A.V.K.). and Support for Core Facilities utilized in this study was provided by Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) CA010815 to The Wistar Institute.

Footnotes

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Conflict of interest. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

Supplementary information including supplementary materials and methods, supplementary figures 1–5 and supplementary references accompanies this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.van Oosten-Hawle P, Morimoto RI. Organismal proteostasis: role of cell-nonautonomous regulation and transcellular chaperone signaling. Genes Dev. 2014;28:1533–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chevet E, Hetz C, Samali A. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-activated cell reprogramming in oncogenesis. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:586–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haynes CM, Ron D. The mitochondrial UPR - protecting organelle protein homeostasis. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:3849–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartl FU, Bracher A, Hayer-Hartl M. Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature. 2011;475:324–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciechanover A, Kwon YT. Degradation of misfolded proteins in neurodegenerative diseases: therapeutic targets and strategies. Exp Mol Med. 2015;47:e147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabas I, Ron D. Integrating the mechanisms of apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:184–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hetz C, Chevet E, Oakes SA. Proteostasis control by the unfolded protein response. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:829–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Potter M, Newport E, Morten KJ. The Warburg effect: 80 years on. Biochem Soc Trans. 2016;44:1499–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson RG, Ghiraldeli LP, Pardee TS. Mitochondria in cancer metabolism, an organelle whose time has come? Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2018;1870:96–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vyas S, Zaganjor E, Haigis MC. Mitochondria and Cancer. Cell. 2016;166:555–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altieri DC. Hsp90 regulation of mitochondrial protein folding: from organelle integrity to cellular homeostasis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:2463–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu K, Ologbenla A, Houry WA. Dynamics of the ClpP serine protease: a model for self-compartmentalized proteases. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;49:400–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balch WE, Morimoto RI, Dillin A, Kelly JW. Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science. 2008;319:916–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cole A, Wang Z, Coyaud E, Voisin V, Gronda M, Jitkova Y et al. Inhibition of the Mitochondrial Protease ClpP as a Therapeutic Strategy for Human Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:864–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seo JH, Rivadeneira DB, Caino MC, Chae YC, Speicher DW, Tang HY et al. The Mitochondrial Unfoldase-Peptidase Complex ClpXP Controls Bioenergetics Stress and Metastasis. PLoS Biol. 2016;14:e1002507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang BH, Plescia J, Dohi T, Rosa J, Doxsey SJ, Altieri DC. Regulation of tumor cell mitochondrial homeostasis by an organelle-specific Hsp90 chaperone network. Cell. 2007;131:257–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chae YC, Angelin A, Lisanti S, Kossenkov AV, Speicher KD, Wang H et al. Landscape of the mitochondrial Hsp90 metabolome in tumours. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bota DA, Davies KJ. Mitochondrial Lon protease in human disease and aging: Including an etiologic classification of Lon-related diseases and disorders. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;100:188–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bezawork-Geleta A, Brodie EJ, Dougan DA, Truscott KN. LON is the master protease that protects against protein aggregation in human mitochondria through direct degradation of misfolded proteins. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu B Mitochondrial Lon Protease and Cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1038:173–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinti M, Gibellini L, Nasi M, De Biasi S, Bortolotti CA, Iannone A et al. Emerging role of Lon protease as a master regulator of mitochondrial functions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1857:1300–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kao TY, Chiu YC, Fang WC, Cheng CW, Kuo CY, Juan HF et al. Mitochondrial Lon regulates apoptosis through the association with Hsp60-mtHsp70 complex. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pryde KR, Taanman JW, Schapira AH. A LON-ClpP Proteolytic Axis Degrades Complex I to Extinguish ROS Production in Depolarized Mitochondria. Cell Rep. 2016;17:2522–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quiros PM, Espanol Y, Acin-Perez R, Rodriguez F, Barcena C, Watanabe K et al. ATP-dependent Lon protease controls tumor bioenergetics by reprogramming mitochondrial activity. Cell Rep. 2014;8:542–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fukuda R, Zhang H, Kim JW, Shimoda L, Dang CV, Semenza GL. HIF-1 regulates cytochrome oxidase subunits to optimize efficiency of respiration in hypoxic cells. Cell. 2007;129:111–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chae YC, Vaira V, Caino MC, Tang HY, Seo JH, Kossenkov AV et al. Mitochondrial Akt Regulation of Hypoxic Tumor Reprogramming. Cancer Cell. 2016;30:257–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gibellini L, Losi L, De Biasi S, Nasi M, Lo Tartaro D, Pecorini S et al. LonP1 Differently Modulates Mitochondrial Function and Bioenergetics of Primary Versus Metastatic Colon Cancer Cells. Front Oncol. 2018;8:254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caino MC, Ghosh JC, Chae YC, Vaira V, Rivadeneira DB, Faversani A et al. PI3K therapy reprograms mitochondrial trafficking to fuel tumor cell invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:8638–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rotanova TV, Botos I, Melnikov EE, Rasulova F, Gustchina A, Maurizi MR et al. Slicing a protease: structural features of the ATP-dependent Lon proteases gleaned from investigations of isolated domains. Protein Sci. 2006;15:1815–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cha SS, An YJ, Lee CR, Lee HS, Kim YG, Kim SJ et al. Crystal structure of Lon protease: molecular architecture of gated entry to a sequestered degradation chamber. EMBO J. 2010;29:3520–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vieux EF, Wohlever ML, Chen JZ, Sauer RT, Baker TA. Distinct quaternary structures of the AAA+ Lon protease control substrate degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E2002–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manning BD, Toker A. AKT/PKB Signaling: Navigating the Network. Cell. 2017;169:381–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santi SA, Lee H. The Akt isoforms are present at distinct subcellular locations. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;298:C580–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janku F, Yap TA, Meric-Bernstam F. Targeting the PI3K pathway in cancer: are we making headway? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:273–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghosh JC, Siegelin MD, Vaira V, Faversani A, Tavecchio M, Chae YC et al. Adaptive mitochondrial reprogramming and resistance to PI3K therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marchi S, Corricelli M, Branchini A, Vitto VAM, Missiroli S, Morciano G et al. Akt-mediated phosphorylation of MICU1 regulates mitochondrial Ca(2+) levels and tumor growth. EMBO J. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanchez-Alvarez M, Del Pozo MA, Bakal C. AKT-mTOR signaling modulates the dynamics of IRE1 RNAse activity by regulating ER-mitochondria contacts. Sci Rep. 2017;7:16497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wallace DC. Mitochondria and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:685–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pinti M, Gibellini L, Liu Y, Xu S, Lu B, Cossarizza A. Mitochondrial Lon protease at the crossroads of oxidative stress, ageing and cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:4807–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sabharwal SS, Schumacker PT. Mitochondrial ROS in cancer: initiators, amplifiers or an Achilles’ heel? Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:709–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gorrini C, Harris IS, Mak TW. Modulation of oxidative stress as an anticancer strategy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:931–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piskounova E, Agathocleous M, Murphy MM, Hu Z, Huddlestun SE, Zhao Z et al. Oxidative stress inhibits distant metastasis by human melanoma cells. Nature. 2015;527:186–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Senft D, Ronai ZA. Regulators of mitochondrial dynamics in cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2016;39:43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Desai SP, Bhatia SN, Toner M, Irimia D. Mitochondrial localization and the persistent migration of epithelial cancer cells. Biophys J. 2013;104:2077–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Caino MC, Seo JH, Aguinaldo A, Wait E, Bryant KG, Kossenkov AV et al. A neuronal network of mitochondrial dynamics regulates metastasis. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao J, Zhang J, Yu M, Xie Y, Huang Y, Wolff DW et al. Mitochondrial dynamics regulates migration and invasion of breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2013;32:4814–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Granot Z, Kobiler O, Melamed-Book N, Eimerl S, Bahat A, Lu B et al. Turnover of mitochondrial steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein by Lon protease: the unexpected effect of proteasome inhibitors. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:2164–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cox J, Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1367–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calvo SE, Clauser KR, Mootha VK. MitoCarta2.0: an updated inventory of mammalian mitochondrial proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D1251–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.