Abstract

Purpose

To improve the test-retest reproducibility of coronary plaque 18F-sodium fluoride (18F-NaF) positron emission tomography (PET) uptake measurements.

Methods

We recruited 20 patients with coronary artery disease who underwent repeated hybrid PET/CT angiography (CTA) imaging within 3 weeks. All patients had 30-min PET acquisition and CTA during a single imaging session. Five PET image-sets with progressive motion correction were reconstructed, (i) a static dataset using all the data (no-MC), (ii) end-diastolic PET (Standard), (iii) cardiac motion corrected (MC), (iv) combined cardiac and gross patient motion corrected (2×MC) and, (v) cardiorespiratory and gross patient motion corrected (3×MC). In addition to motion correction, all datasets were corrected for variations in the background activities which are introduced by variations in the injection-to-scan delays (background blood pool clearance correction, BC). Test-retest reproducibility of PET target-to-background ratio (TBR) was assessed by Bland-Altman analysis and coefficient of reproducibility.

Results

A total of 47 unique coronary lesions were identified on CTA. Motion correction in combination with BC improved the PET TBR test-retest reproducibility for all lesions (coefficient of reproducibility: Standard = 0.437, No-MC = 0.345 (27% improvement), Standard+BC = 0.365 (20% improvement), no-MC+BC = 0.341 (27% improvement), MC+BC = 0.288 (52% improvement), 2×MC+BC = 0.278 (57% improvement) and 3×MC+BC = 0.254 (72% improvement), all p<0.001). Importantly in a sub analysis of 18F-NaF-avid lesions with gross patient motion >10mm following corrections reproducibility was improved by 133% (coefficient of reproducibility: standard= 0.745, 3×MC= 0.320).

Conclusion

Joint corrections for cardiac, respiratory and gross patient motion in combination with background blood pool corrections markedly improve test-retest reproducibility of coronary 18F-NaF PET.

Keywords: Data-driven motion detection, Motion correction, PET/CT, Cardiac PET, 18F-Sodium fluoride, Vulnerable plaque

INTRODUCTION

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) in combination with Computed Tomography (CT) angiography (CTA) holds promise as a non-invasive technology for identification of high-risk plaques in patients with coronary artery disease [1–4].

Clinical implementation of coronary PET imaging is, however, challenging, as coronary lesions are small and continuously move during the acquisition. Further, only modest target to background ratio (TBR) differences between culprit and non-culprit plaques (~34%) have been reported for 18F-sodium fluoride PET (18F-NaF) [1]. Importantly, the TBR measurements are significantly degraded by cardiorespiratory and patient motion during the 30-min scans. It has been shown that physiological tidal breathing can cause the heart to move >1 cm [5]. The amplitude of coronary artery motion during the cardiac cycle is about 8–26 mm, depending on the artery and location, with the highest motion in the right coronary artery [6]. Further, typical gross patient motion (other than cardiorespiratory motion) results in repositioning of the heart, typically by 5–15mm, during a 30-min scan [7]. These observations are of key significance for coronary lesions with dimensions measured in single millimeters.

To reduce the effect of motion of the coronary arteries, end-diastolic phase images have been selected in studies to date [1,6,8] but this strategy uses only 25% of PET counts, consequently increasing image noise [9]. Recent studies proposed improvements by correcting for cardiac motion [6,9], or by combining end-diastolic imaging with corrections for gross patient motion [7], but did not include corrections for respiratory motion, nor test how these corrections affect the scan-rescan reproducibility. Additionally, TBR values are affected by variations in the tracer uptake time (injection to scan delay) [10,11]. Consequently, the reproducibility of this promising PET technique remains suboptimal, which hampers its translation into clinical routine.

In this study, we demonstrate that a novel technique for coronary PET processing which combines triple motion correction (3×MC) (cardiorespiratory and gross patient motion) with adjustments for injection-to-scan delays significantly improves the scan-rescan reproducibility.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

The study population comprised of twenty patients who underwent repeated hybrid 18F-NaF PET/CT examinations of the coronary arteries. Scans were repeated within 3 weeks as a part of the ongoing DIAMOND (Dual Antiplatelet Therapy to Reduce Myocardial Injury, [12]) study. One patient was excluded from the study due to an incomplete saving of the list mode PET file (PET raw data). Patient characteristics are described in Table 1.

Table 1:

Patient demographics

| Demographics | Value |

|---|---|

| Age in years, mean ±SD | 69.7±7.5 |

| Gender (Males) | 16 (84) |

| Body-mass Index (BMI) | 27.6±4.0 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |

| Diabetes Mellitus (Type I/ Type II), | 0 (0) / 2 (11) |

| Current Smoker | 2 (11) |

| Hypertension | 13 (68) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 19 (100) |

Continuous variables reported as mean ± SD; categorical variables reported as n (%)

Inclusion criteria for the study included angiographically confirmed multivessel coronary artery disease defined as either previous revascularization or stenosis > 50%. Exclusion criteria included: an acute coronary syndrome within 12 months prior to the examination, renal dysfunction (estimated glomerular filtration rate ≤30 mL/min/1.73 m2) and contraindication to CT-contrast media. This study was approved by the local investigational review board (Edinburgh, UK) and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Imaging Protocol

PET/CT.

Patients underwent 30-min list-mode PET-emission acquisitions approximately one hour after (66±9 min, range: 59–101 min) injection of 18F-NaF (248±9 MBq). All patients were scanned in supine position with arms positioned above the head in a 128-slice Biograph mCT system (Siemens Healthineers, Knoxville, USA). A low-dose CT for attenuation correction was acquired immediately before the PET acquisition (120 kV, 50 mAs, 3-mm slice thickness). All patients were imaged with 3-lead electrocardiogram (cardiac gating), without the use of additional external markers for tracking of patient or respiratory motion.

CT angiography.

For anatomical localization of PET uptake, coronary CTA was performed immediately after the PET acquisition. The CTA imaging parameters including prospective gating, 330 milliseconds rotation time, body-mass index (BMI) dependent voltage (BMI <25, 100 kV; BMI ≥25, 120 kV), and tube-current time product of 160–245 mAs. Patients were administered beta-blockers (orally or intravenously) to achieve a target heart-rate of <60 beats/min. A BMI-dependent bolus-injection of contrast media (400 mg/mL) was administered to the patients with a flow of 5–6 mL/s after determining the appropriate trigger delay defined by a test bolus of 20 mL of contrast material. CTA studies were assessed visually for percent stenosis according to SCCT guidelines [13].

Image reconstruction

Five different PET image reconstructions were evaluated in this study: (i) a static reconstruction using all the acquired data (no-MC), (ii) end-diastolic reconstruction using 25% of the acquired data (standard) [1], (iii) cardiac motion corrected reconstruction (MC), (iv) combined cardiac and gross patient motion corrected reconstruction (2×MC), and (v) combined cardiac, respiratory and gross patient motion corrected reconstruction (3×MC). All reconstructions except the end-diastolic reconstruction were using 100% of the acquired data.

The five datasets were reconstructed with vendor provided software (JS-Recon12, Siemens, Knoxville, USA) from the PET list mode data (raw PET data). All PET image reconstructions were performed with corrections for time-of-flight and point-spread function, using 2 iterations, 21 subsets. The no-MC reconstruction was performed without any gating, whereas all other reconstructions were performed with 4 cardiac gates (time/phase based) (all datasets); the number of gross patient motion frames depended on the motion of the individual patients and scans (range 2–10 frames [7]) (2×MC, 3×MC), while the number of respiratory gates was fixed to 4 (amplitude-based gating [14]) (3×MC). Because the gross patient and respiratory motion was detected directly in sinogram space, it was not possible to apply any direct motion correction of the corresponding AC maps owing to the complex translations from the motion vectors obtained in projection space to image-space [7].

Motion detection

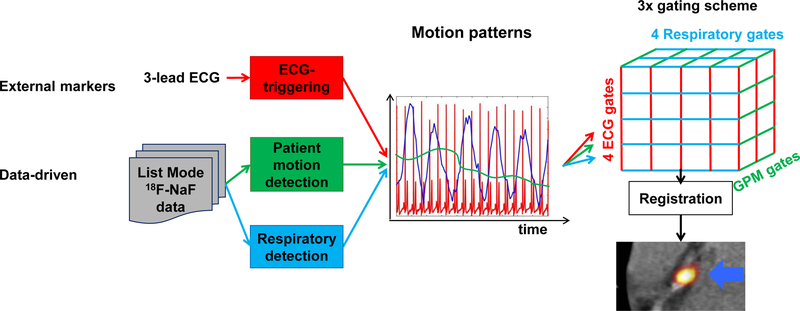

The overall scheme for motion detection is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Overall scheme for comprehensive motion detection and correction of coronary PET images.

A fixed number of respiratory and electrocardiogram (ECG) gates were used. The number of gross patient motion (GPM) gates depended on the number of repositioning events the patient had during the acquisition. A 3D-mesh of gated reconstructions were obtained, which were registered to generate the 3×MC image set. Following the co-registration, the MC images (MC, 2×MC and 3×MC) were obtained by averaging all the gated images.

Cardiac gating information was obtained from a 3-lead electrocardiogram. Respiratory and gross patient motion detection was achieved using only the acquired PET list data without the use of any external markers. The data-driven motion detection techniques were based on center-of-mass analyses of single-slice rebinned sinograms [15] created for every 200 ms of the acquisition, as described in our previous study [7]. In brief, the detection of the gross patient motion was obtained for the entire field-of-view [7], while the respiratory motion was detected only for the diaphragm using a 2cm (radius) boundary.

Motion correction

The PET motion correction was obtained through co-registration of gated PET-images (PET-PET image co-registration), using a dedicated coronary PET/CT software (FusionQuant, Cedars-Sinai Medical center) which employs a non-linear co-registration of the images [8] (Figure 1). The resulting motion corrected datasets (MC, 2×MC, and 3×MC) were obtained through averaging of the co-registered images. To ensure accurate co-registration of the coronary plaques, the motion compensation was focused on the coronary tree utilizing segmentations of the coronary arteries (including a radius of 1cm surrounding the center of the coronary arteries) obtained from the CTA images using a CT analysis tool (Autoplaque, Version 2.0, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center).

Image analysis

PET Quantification.

Prior to image analysis, PET and CTA reconstructions were reoriented, fused and co-registered in all 3 planes (a rigid X-Y-Z translation was performed). Key points of reference were the sternum, vertebrae, blood pool in the left and right ventricle (based upon high 18F-fluoride activity in the blood pool in comparison to the surrounding myocardium) and the great vessels [16]. 18F-NaF PET uptake was measured in all coronary segments with a CTA >25% stenosis, a vessel diameter ≥2 mm, which have not been stented and presented with image quality suitable for visual stenosis assessment. The 18F-NaF uptake in the lesions was evaluated in the 3D spherical volume of interest (VOI) (radius 5 mm), and the background blood pool activity was determined by a cylindrical VOI (radius=10 mm, length=15 mm), placed in the right atrium at the level of the takeoff of the right coronary artery. We used the same VOIs for all 5 reconstructions evaluated in this study. TBR values for all 5 reconstructions were calculated by dividing the maximal standard uptake value (SUVmax) of the lesions by the mean SUV obtained from the blood pool (SUVBackground)[17].

The impact of the motion (cardiorespiratory and gross patient motion) was evaluated in three subsets of lesions, (a) in all CTA-defined lesion locations (b) in all lesions with 18F-NaF-avid uptake and (c) in 18F-NaF-avid lesions with gross patient motion >10 mm. The magnitude of the gross patient motion repositioning events was calculated in 3D from motion vectors obtained during the PET-PET co-registrations.

Blood pool correction.

It has been recently reported that TBRs for 18F-NaF varies with injection-to-scan time [10]. Based on the data reported in [10], the decay-corrected tracer activity in the lesions does not change during a 2-hour period, while the blood pool activity is cleared at a rate of 1.5092*e−0.004*t (R2=0.81). From these findings, we propose to introduce a correction factor which harmonizes the SUVBackground activities to a reference time (60 minutes post-injection) (Equation 1).

| (1) |

where t represents the injection-to-scan delay in minutes.

Diagnostic evaluation of 18F-NaF PET

All lesions were quantified based on the CTA based lesion position, categorized as 18F-NaF-avid and 18F-NaF-negative on standard PET using a previously validated methodology [1,18]. In brief, lesions with TBR ≥1.25 and focal uptake on the site of the CTA-assessed lesion were considered 18F-NaF-avid, while lesions without focal uptake or TBR values < 1.25 were considered 18F-NaF-negative [1].

Statistical analysis

The data were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Statistical analysis was performed in MatLab (Mathworks). Continuous variables were presented as mean±SD (standard deviation). Assessment of the test-retest reproducibility before and after corrections for motion and blood-pool effects were obtained using descriptive statistics with Bland-Altman plots as well as the coefficient of reproducibility. Improvements in the test-retest reproducibility were evaluated by Pitman-Morgan test. A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient cohort

The patients underwent repeated 18F-NaF PET / CTA hybrid imaging studies within a maximum of 21 days (mean 12±5 days). 47 unique lesions were identified on the CTA-images with 15 18F-NaF-avid, 30 18F-NaF-negative and 2 lesions with discordant evaluations (TBR>1.25 in one scan, while TBR <1.25 in the other scan) on standard PET images.

Standard analyses

On standard PET images, TBR across all lesions were 1.18±0.48, with 18F-NaF-avid lesions having TBR values of 1.65±0.38 (Table 2). Test-retest coefficients of reproducibility for TBR were 0.437 for all lesions and 0.628 for18F-NaF-avid lesions. In comparison, evaluations of no-MC data, the TBR values were significantly lower 1.06±0.32 (All lesions) and 1.37±0.23 (18F-NaF-avid) (p<0.001 and p<0.004, respectively) with test-retest reproducibility coefficients of 0.345 and 0.490, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2:

Average target to background ratios (TBR) and coefficient of reproducibility (Repro) for the end-diastolic (standard), static images (NO-MC), cardiac motion corrected (MC), cardiac and gross patient motion corrected (2×MC) and triple motion corrected (3×MC) images.

| IMAGE SET | ALL LESIONS | 18F-NAF-AVID | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBR | Repro | P-value | Improvement | TBR | Repro | P-value | Improvement | |

| STANDARD | 1.18±0.48 | 0.437 | - | - | 1.65±0.38 | 0.628 | - | - |

| NO-MC | 1.06±0.32 | 0.345 | <0.001 | 26.5% | 1.37±0.23 | 0.490 | =0.004 | 28.2% |

| MC | 1.11±0.39 | 0.336 | <0.001 | 30.1% | 1.46±0.32 | 0.479 | <0.001 | 31.1% |

| 2×MC | 1.12±0.40 | 0.307 | <0.001 | 42.3% | 1.51±0.30 | 0.422 | <0.001 | 49.0% |

| 3× MC | 1.20±0.46 | 0.299 | <0.001 | 46.1% | 1.68±0.29 | 0.422 | <0.001 | 49.0% |

Improvements of the TBR reproducibility were calculated against the standard. All incremental improvements (p-value) were tested using Pitman-Morgan tests, where p<0.05 were considered statistically significant). Continuous variables reported as mean ± SD.

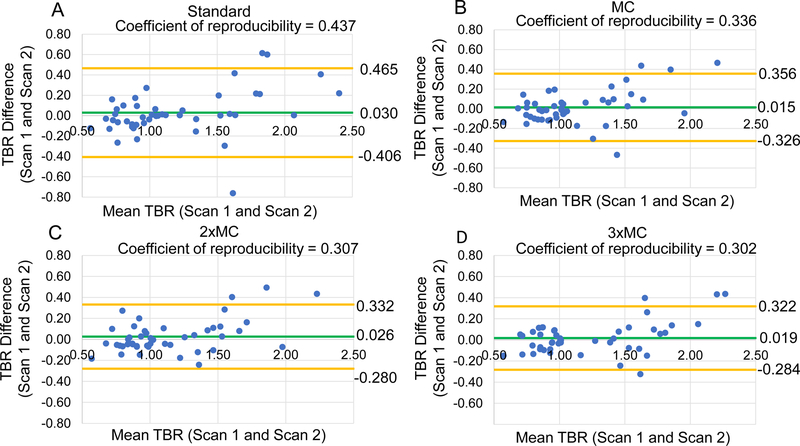

Reproducibility with Motion Correction

The motion corrected datasets had significantly improved test-retest reproducibility of the lesion assessments in comparison to the standard datasets, all p<0.05 (Pitman-Morgan test) (Table 2). Figure 2 shows that the progressive motion compensation techniques steadily improved the test-retest reproducibility for all delineated lesions.

Figure 2: Reproducibility of coronary 18F-NaF uptake measurement with motion correction.

Bland-Altman plots of the target-to-background (TBR) evaluations for all the lesions with and without motion correction. (A) Standard, (B) cardiac motion corrected (MC), (C) cardiac and gross patient motion corrected (2×MC) and, (D) cardiorespiratory and gross patient motion corrected (3×MC). Significant reductions in the 95% confidence intervals (orange lines) were observed for all motion corrected datasets in comparison to the standard evaluation (Table 2). The green line shows mean difference for all measurements. Standard = end-diastolic imaging.

Background blood pool clearance correction

All datasets were corrected for the variances in the injection to scan delay by standardizing the tracer SUV measurements in the background region to 60-min after 18F-NaF administration (Table 3). Due to the mean delay time (66±9 min, range 59–101 min) being longer than 60 minutes, our blood pool correction resulted in a slight reduction of TBR values by 2.5±3.8% (range: −0.4% to 17.8%), p=0.98 (Table 4).

Table 3.

Background standardized uptake value (SUVbackground) activities with and without the correction for injection-to-scan delay.

| IMAGE SET | ACQUIRED SUVBACKGROUND | CORRECTED SUVBACKGROUND | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUV | Repro | P-value | Improvement | SUV | Repro | P-value | Improvement | |

| STANDARD | 1.06±0.15 | 0.201 | - | - | 1.09±0.14 | 0.189 | 0.75 | 6.0% |

| NO-MC | 1.07±0.14 | 0.183 | 0.07 | 10.0% | 1.07±0.14 | 0.173 | 0.31 | 16.0% |

| MC | 1.05±0.14 | 0.182 | 0.23 | 10.1% | 1.07±0.14 | 0.173 | 0.33 | 15.9% |

| 2×MC | 1.06±0.13 | 0.160 | 0.23 | 25.9% | 1.07±0.13 | 0.143 | 0.05 | 40.5% |

| 3×MC | 1.05±0.13 | 0.159 | 0.12 | 26.7% | 1.07±0.13 | 0.148 | 0.03 | 36.1% |

Test-retest coefficients of reproducibility (Repro) of the SUVbackground were calculated for all datasets before and after corrections. All improvements were calculated against the standard, non-corrected background activities. Results of comparisons by Pitman-Morgan tests with p-values <0.05 (bold) were considered statistically significant.

Standard = end-diastolic PET, No-MC =Static images, MC= cardiac motion corrected (MC), 2×MC = combined cardiac and gross patient motion corrected, 3×MC = cardiorespiratory and gross patient motion corrected. Continuous variables reported as mean ± SD.

Table 4:

Target to background ratios (TBR) obtained before and after corrections for motion and injection-to-scan delay (BC).

| IMAGE SET | ALL LESIONS | NAF-AVID | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBR | Repro | P-value | Improvement | TBR | Repro | P-value | Improvement | |

| STANDARD | 1.18±0.48 | 0.437 | - | 1.65±0.38 | 0.628 | - | ||

| NO-MC+BC | 1.04±0.31 | 0.341 | <0.001 | 27.4% | 1.32±0.23 | 0.489 | <0.001 | 28.5% |

| STANDARD+BC | 1.15±0.46 | 0.365 | <0.001 | 19.7% | 1.59±0.34 | 0.501 | <0.001 | 25.3% |

| MC + BC | 1.11±0.36 | 0.288 | <0.001 | 51.7% | 1.41±0.30 | 0.392 | <0.001 | 60.2% |

| 2×MC+ BC | 1.09±0.36 | 0.278 | <0.001 | 57.0% | 1.46±0.28 | 0.365 | <0.001 | 71.9% |

| 3×MC +BC | 1.18±0.44 | 0.254 | <0.001 | 72.0% | 1.63±0.26 | 0.354 | <0.001 | 77.6% |

Significant improvements in the TBR coefficient of reproducibility (repro) was observed for all corrected image sets. Improvements of reproducibility were calculated against the standard assessment. All incremental improvements were significant (P-value) by Pitman-Morgan test.

Standard = end-diastolic PET, No-MC = Static, MC= cardiac motion corrected (MC), 2×MC = combined cardiac and gross patient motion corrected, 3×MC = cardiorespiratory and gross patient motion corrected. Continuous variables reported as mean ± SD.

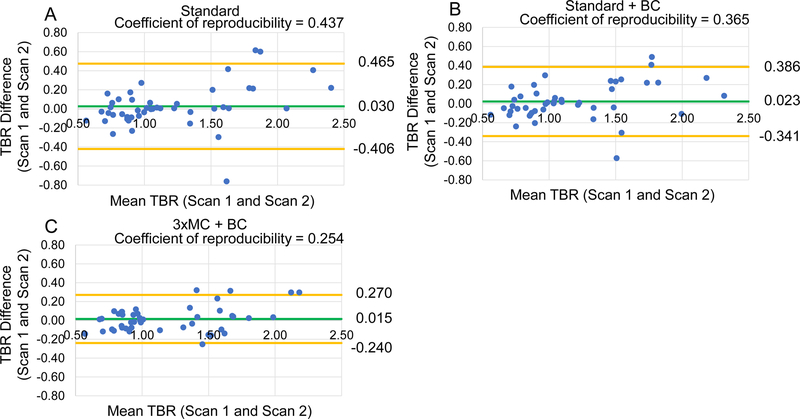

Reproducibility with motion correction and BC

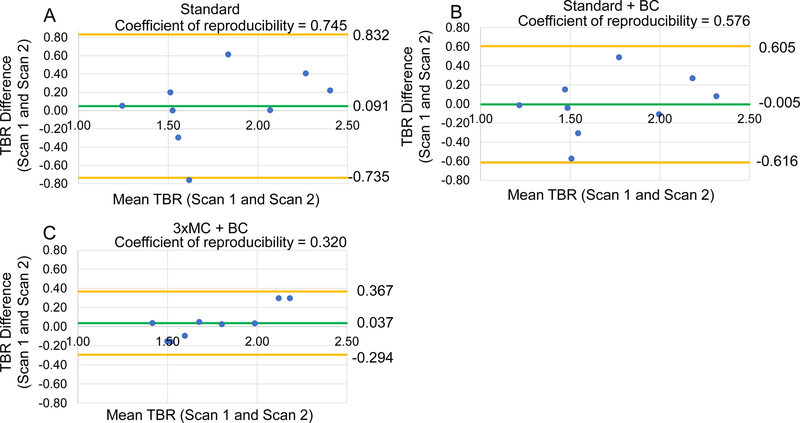

Blood pool correction further improved the test-retest reproducibility of TBR for all datasets. For all lesions as a stand-alone correction (Standard vs. Standard+BC), the coefficient of reproducibility was improved by 20%, in combination with 3×MC, the reproducibility was improved by 72% (Table 4, Figure 3). In the sub-analysis of 18F-NaF-avid lesions, 3×MC +BC correction improved the reproducibility by 78% (Table 4, Figure S1). Importantly in a subset of lesions with larger patient motion during one of the scans (>10 mm), 3×MC+BC correction lead to a 133% improvement in reproducibility (Table 5, Figure 4).

Figure 3: Reproducibility of coronary 18F-NaF uptake measurements and adjustments for blood pool clearance.

Bland-Altman plots of the TBR assessment for all lesions observed in the study. Standard images without and with corrections for injection-to-scan delay (Standard+BC) are shown in panels A and B respectively. The fully corrected dataset (cardiorespiratory and gross patient motion corrected with BC (3×MC+BC)) is shown in panel C. Significant reductions in the 95% confidence interval (orange lines) were observed for each incremental correction step (Table 5). The green line shows average TBR values across all measurements. BC = background blood pool correction. Standard = end-diastolic imaging.

Table 5:

Impact of motion correction and background blood pool correction (BC) on target-to-background ratios (TBR) of 18F-NaF-avid lesions with gross patient motion >10mm in at least one of the scans.

| IMAGE SET | TBR | REPRO | P-VALUE | IMPROVEMENT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STANDARD (NO CORRECTION) | 1.78±0.43 | 0.745 | - | - |

| NO-MC + BC | 1.37±0.25 | 0.588 | <0.001 | 26.7% |

| STANDARD + BC | 1.72±0.39 | 0.576 | <0.001 | 29.4% |

| MC + BC | 1.54±0.33 | 0.386 | <0.001 | 93.1% |

| 2×MC + BC | 1.57±0.32 | 0.348 | <0.001 | 114.0% |

| 3×MC + BC | 1.76±0.29 | 0.320 | <0.001 | 132.8% |

Improvements of the TBR reproducibility (repro) were calculated against the standard assessment method. All incremental improvements were significant (p-value) by Pitman-Morgan tests.

BC = background blood pool correction, Standard = end-diastolic PET, No-MC = static, MC= cardiac motion corrected (MC), 2×MC = combined cardiac and gross patient motion corrected, 3×MC = cardiorespiratory and gross patient motion corrected. Continuous variables reported as mean ± SD.

Figure 4: Reproducibility of coronary 18F-NaF uptake measurement in patients with substantial gross patient motion.

Bland-Altman plots of the target-to-background (TBR) assessment for 18F-NaF-avid lesions with gross patient motion >10 mm. Standard evaluations of the lesions without (Standard) and with correction for variances in the blood pool activity (Standard +BC) are shown in panels A and B. Panel C demonstrates the fully corrected dataset (cardiorespiratory and gross patient motion with BC (3×MC+BC)). Significant reductions in the 95% confidence interval (orange lines) were observed for each incremental correction step (Table 5). The green line shows average TBR values across all measurements. BC = background blood pool correction. Standard = end-diastolic imaging.

Two lesions with discordant assessment and two lesions considered 18F-NaF-negative on the standard assessment were reclassified as being 18F-NaF-avid on 2 scans following corrections for both cardiorespiratory and gross patient motion (3×MC). For the lesions with discordant analyses on test and retest scans (2 lesions), following 3×MC+BC corrections the TBR values increased from (TBR: standard = 1.24 and 1.22, on scan 1 and scan 2 respectively), to (TBR = 1.44 and 1.42, on scan 1 and scan 2 respectively). The two lesions perceived 18F-NaF-negative had an average increment of 16±1% in the TBR assessment following 3×MC+BC (TBR: standard =1.16±0.1, 3×MC+BC = 1.34±0.1).

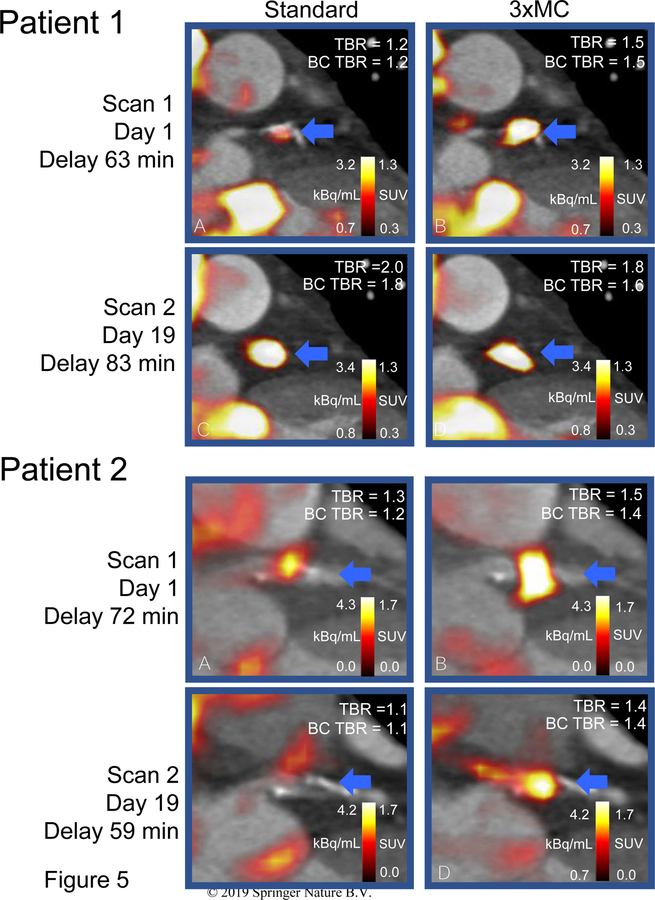

Figure 5 displays two case-examples on the effect of the described motion correction techniques. In both cases, the detrimental motion caused discordant evaluations of the lesions in the test-retest evaluation. Following 3×MC and BC corrections, both lesions were reclassified with concordant evaluations (18F-NaF-avid).

Figure 5: Test-rest coronary PET reproducibility before and after corrections.

Patient 1. Patient with significant respiratory and gross patient motion during the first scan (10.3 mm) and a 20-minute difference in the injection-to-scan delay leading to discrepant evaluations in the test-retest scans. Patient 2. Patient with several repositioning events (gross patient motion) during the acquisition, which in combination with the cardiorespiratory motion reduced the appearing tracer-uptake in the lesion. Both patients. In both cases 3×MC+BC reduced the intra-scan variability TBR evaluation of the lesion. Following 3×MC+BC the test-retest lesion evaluation was concordant (18F-NaF-avid) in comparison to discordant test-retest evaluations obtained from the standard images in both cases. TBR = target to background value, BC = blood pool correction. Standard = end-diastolic imaging, 3×MC = cardiorespiratory and gross patient motion corrected.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated the reproducibility of TBR measurements of coronary plaque activity before and after corrections for cardiorespiratory and gross patient motion as well as quantitative correction of the background activity according to the variations in the injection-to-scan delay. To our knowledge, this is the first time such comprehensive triple gating motion correction is reported for any PET imaging. We demonstrate that the reproducibility using the standard assessment (end-diastolic imaging) is impaired by motion during the acquisition, reduced count rate, and injection time variability. Motion corrected reconstructions utilizing all image data and adjustment for injection-to-scan delay markedly improved test-retest reproducibility.

High reproducibility of coronary PET lesion uptake is a critical prerequisite for the translation of coronary plaque imaging into clinical practice. The standard approach used to date is based on end-diastolic imaging [1,18]. The rationale behind using end-diastolic images for the assessment of coronary plaque activity was to improve TBR and mitigate the detrimental effects of cardiac motion, as demonstrated in this study (Table 2) [1,19]. Unfortunately, this approach has several implications on TBR values, with two substantial problems pertaining to the increased noise in the images introduced by capturing counts from only one-fourth of the cardiac cycle and the remaining embedded motion-blur introduced by both respiratory and gross patient motion [7]. These limitations result in compromised test-retest reproducibility, which consequently makes it difficult to set accurate TBR thresholds for positive or negative findings. In addition, the use of TBR as a clinical measure for the lesion uptake might not be ideal because of the varying uptake in the background introduced by variations in the injection-to-scan delays [10,11,20]. In this study, the variations in the injection-to-scan delays were found to reduce the repeatability by 19% for all lesions (Table 3), which were corrected using a simple correction for blood clearance (BC).

To ameliorate the shortcomings of the noise and patient motion, motion correction of cardiac contraction has been employed [6,9,10]. Additionally, in a recent study, it was found that the long acquisition duration (30 minutes) lead to multiple events of patient repositioning during emission scanning [7], a pattern that was also found in the current study. In this study, we combined corrections for gross patient motion with additional novel corrections for respiratory motion detected PET from list mode data to achieve total triple gated motion corrected reconstructions. These additional corrections improved test/retest reproducibility by an additional 12% to 42% in comparison to cardiac contraction correction (MC) as a standalone technique (Table 2). Overall, when BC and 3×MC were combined, the reproducibility was improved by 77% for 18F-NaF-avid lesions (Table 4, Figures 3–4).

Despite significant improvement, the reproducibility remains modest (Coefficient of reproducibility of 25%) after applying the triple corrections proposed in this study. Therefore, further reductions in the inter-scan variation is still warranted. The reproducibility coefficients were lower for the 18F-NaF-avid lesions in the current study. This is expected to partly be caused by the background activities and partly by the increased noise in the SUVmax uptake for the 18F-NaF avid lesions, a consequence of the quasi-Poisson nature of the PET-detections and single voxel of activity sampled [21]. While the use of SUVmean could reduce the noise, and thereby some of the variation in the measurements, it is not feasible as accurate delineation of small coronary plaques is impossible [20]. An alternative method to reduce the noise in the TBR assessment could be the use of an average of the N hottest voxels within the lesion (SUVmax-N , with N>1), a method that has proven to be stable for oncological PET scans [22] in combination with more advanced motion correction techniques. However, the use of SUVmax-N mandates finding an optimum number of voxels and, thus, a new TBR cut-off value to determine the 18F-NaF-avid lesions. This was outside of the scope of this study but should be considered for upcoming studies.

The combination of 3×MC and BC not only improved the reproducibility but also led to reclassification of 4 lesions, of which 2 were perceived negative on both scans and 2 had discordant evaluations on the standard end-diastolic image sets. The 3×MC+BC led to concordant test-retest findings in cases with originally discordant assessments on standard imaging. This finding shows that the complex motion patterns in combination with varying injection to scan delays not only affect the quantitative test-retest reproducibility but might also affect the clinical classification of lesions (Table 4, Figure 5). In addition, the TBR measure may vary due to differences in the reconstruction protocols. In a recent study, it was found that the TBR is also dependent on the post-filtering of the data and the number of iterations and subsets used [9]. The use of time-of-flight and point-spread function corrections is expected to have a significant impact on the SUV assessment of the coronary lesions which often are of the same magnitude as the PET resolution [9]. In the current study, we used an already established reconstruction protocol which was used in previous studies from our center [7,16]. Further optimizations of the reconstruction protocols with a focus on improved reproducibility could be still possible.

Our findings show that a combination of comprehensive corrections for motion correction and injection to scan delays is critical for high reproducibility and consistent evaluation of lesions in coronary plaque imaging. To this end, the proposed correction techniques are applicable without the need for additional hardware or changes in the imaging protocols as motion and blood pool corrections, are performed using data obtained during standard acquisitions and can be performed retrospectively. The novel correction approaches presented in this study are directly applicable to ongoing clinical trials utilizing 18F-NaF coronary plaque imaging: DIAMOND () and PREFFIR () [12,23]. In principle, these motion correction methods may be also adapted to other coronary tracers and also to the 18F-NaF PET imaging of patients with aortic stenosis [24].

Limitations

In this study, the number of cardiac and respiratory gates was limited to 4, due to reductions in count-statistics for each gated reconstruction. This approach, with a relatively limited number of gates, leads to increased intra-frame motion. Further improvement may be possible with larger number of gates or by correcting for motion either before or during image reconstruction [25], although such corrections are not implemented in current reconstruction toolboxes. In our study, the motion correction of the attenuation correction maps was not applied for each of the gated reconstructions.

This was not possible in the current setting as motion detection in projection space (sinogram space) is not easily transformed into motion in image-space. This limitation, however, is thought to have less impact on the reproducibility than performing no corrections for patient motion and respiratory motion, which is the current standard. Future studies should address focus on optimization of motion correction of the attenuation correction for coronary PET imaging in addition to of the PET images.

Another limitation is the number of patients included in this protocol. However, this test-retest study involves repeating of the complex CTA and PET protocol. Obtaining more extensive scan-rescan data with larger cohorts is currently not possible due to cost, ethics and radiation dose concerns. Partially mitigating this limitation, the total number of evaluated lesions was substantially larger than number of patients. Nevertheless, the results presented here were statistically significant, unequivocally demonstrating that the proposed corrections increase the coronary PET TBR reproducibility.

CONCLUSION

Test/retest assessment of coronary lesions is significantly affected by cardiorespiratory and gross patient motion as well as varying injection delays. Correcting for these factors in a retrospective fashion improved the reproducibility by up to 133%. These corrections should be considered for all coronary plaque studies with PET.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported in part by grant R01HL135557 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/National Institute of Health (NHLBI/NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. In addition, the study was supported by Siemens Medical Systems. The study was also supported by a grant (“Cardiac Imaging Research Initiative”) from the Miriam & Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation. DEN is supported by the British Heart Foundation (CH/09/002, RM/13/2/30158, RE/13/3/30183) and is the recipient of a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator Award (WT103782AIA). MRD is supported by the Sir Jules Thorn Biomedical Research Award (JTA/15) and the British Heart Foundation (FS/14/78/31020). None of the other authors have any conflict of interest relevant to this study.

Abbreviations:

- 18F-NaF

18F-sodium fluoride

- PET

Positron Emission Tomography

- CTA

coronary Computed Tomography Angiography

- MC

cardiac motion corrected

- 2×MC

cardiac and gross patient motion corrected

- 3×MC

cardiac, respiratory and gross patient motion corrected

- BC

Background blood pool clearance correction

- TBR

Target to Background ratio

- SUV

Standardized uptake value

- VOI

Volume of Interest

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Supplementary data

Figure S1 is available online. This figure includes Bland-Altman plots of the Target to Background (TBR) assessment for 18F-NaF-avid lesions only.

Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were approved by the local institutional review board, the Scottish Research Ethics Committee (REC reference: 14/SS/0089 and 15/SS/0203), and the United Kingdom (UK) Administration of Radiation Substances Advisory Committee. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent prior to any study procedures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Joshi NV, Vesey AT, Williams MC, Shah AS V, Calvert PA, Craighead FHM, et al. 18F-fluoride positron emission tomography for identification of ruptured and high-risk coronary atherosclerotic plaques: a prospective clinical trial. Lancet [Internet] Joshi et al. Open Access article distributed under the terms of CC BY; 2014;383:705–13. Available from: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61754-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cocker MS, Spence JD, Hammond R, Wells G, DeKemp RA, Lum C, et al. [18F]-NaF PET/CT identifies active calcification in carotid plaque. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;10:486–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudd JHF, Warburton EA, Fryer TD, Jones HA, Clark JC, Antoun N, et al. Imaging atherosclerotic plaque inflammation with [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Circulation 2002;105:2708–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarkin JM, Joshi FR, Evans NR, Chowdhury MM, Figg NL, Shah AV., et al. Detection of Atherosclerotic Inflammation by68Ga-DOTATATE PET Compared to [18F]FDG PET Imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:1774–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawood M, Büther F, Stegger L, Jiang X, Schober O, Schäfers M, et al. Optimal number of respiratory gates in positron emission tomography: a cardiac patient study. Med Phys [Internet] 2009;36:1775–84. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19544796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubeaux M, Joshi N V, Dweck MR, Fletcher A, Motwani M, Thomson LE, et al. Motion correction of 18F-NaF PET for imaging coronary atherosclerotic plaques. J Nucl Med [Internet] 2016;57:54–9. Available from: http://jnm.snmjournals.org/cgi/doi/10.2967/jnumed.115.162990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lassen ML, Kwiecinski J, Cadet S, Dey D, Wang C, Dweck MR, et al. Data-driven gross patient motion detection and compensation: Implications for coronary 18 F-NaF PET imaging. J Nucl Med 2018;jnumed.118.217877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massera D, Doris MK, Cadet S, Kwiecinski J, Pawade TA, Peeters FECM, et al. Analytical quantification of aortic valve 18F-sodium fluoride PET uptake. J Nucl Cardiol [Internet] Springer; US; 2018; Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s12350-018-01542-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doris MK, Otaki Y, Krishnan SK, Kwiecinski J, Rubeaux M, Alessio A, et al. Optimization of reconstruction and quantification of motion-corrected coronary PET-CT. J Nucl Cardiol [Internet] Springer; US; 2018;1–11. Available from: 10.1007/s12350-018-1317-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwiecinski J, Berman DS, Lee S-E, Dey D, Cadet S, Lassen ML, et al. Three-hour delayed imaging improves assessment of coronary 18 F-sodium fluoride PET. J Nucl Med 2018;jnumed.118.217885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bucerius J, Mani V, Moncrieff C, Machac J, Fuster V, Farkouh ME, et al. Optimizing18F-FDG PET/CT imaging of vessel wall inflammation: the impact of18F-FDG circulation time, injected dose, uptake parameters, and fasting blood glucose levels. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2014;41:369–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ClinicalTrials.gov National Library of Medicine (U.S.). Dual Antiplatelet Therapy to Reduce Myocardial Injury https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT02110303. Accessed 4th December 2018 [Internet]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT02110303.

- 13.Leipsic J, Abbara S, Achenbach S, Cury R, Earls JP, Mancini GBJ, et al. SCCT guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of coronary CT angiography: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr Elsevier; 2014;8:342–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lassen ML, Kwiecinski J, Slomka PJ. Gating Approaches in Cardiac PET Imaging. PET Clin 2019;14:271–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daube-Witherspoon ME, Muehllehner G. Treatment of axial data in three-dimensional PET. J Nucl Med [Internet] 1987;28:1717–24. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3499493 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwiecinski J, Adamson PD, Lassen ML, Doris MK, Moss AJ, Cadet S, et al. Feasibility of coronary 18F-sodium fluoride PET assessment with the utilization of previously acquired CT angiography. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pawade TA, Cartlidge TRG, Jenkins WSA, Adamson PD, Robson P, Lucatelli C, et al. Optimization and reproducibility of aortic valve 18F-Fluoride positron emission tomography in patients with aortic stenosis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;9:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dweck MR, Chow MWL, Joshi NV., Williams MC, Jones C, Fletcher AM, et al. Coronary arterial 18F-sodium fluoride uptake: A novel marker of plaque biology. J Am Coll Cardiol Elsevier Inc.; 2012;59:1539–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitagawa T, Yamamoto H, Nakamoto Y, Sasaki K, Toshimitsu S, Tatsugami F, et al. Predictive Value of 18 F‐Sodium Fluoride Positron Emission Tomography in Detecting High‐Risk Coronary Artery Disease in Combination With Computed Tomography. J Am Heart Assoc [Internet] 2018;7 Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/JAHA.118.010224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen W, Dilsizian V. PET Assessment of Vascular Inflammation and Atherosclerotic Plaques: SUV or TBR? J Nucl Med 2015;56:503–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soret M, Bacharach SL, Buvat I. Partial-Volume Effect in PET Tumor Imaging. J Nucl Med 2007;48:932–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laffon E, Lamare F, De Clermont H, Burger IA, Marthan R. Variability of average SUV from several hottest voxels is lower than that of SUVmax and SUVpeak. Eur Radiol 2014;24:1964–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.ClinicalTrials.gov. National Library of Medicine (U.S.). Study Prediction of Recurrent Events With 18F-Fluoride https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT02278211. Accessed 4 Dec 2018.

- 24.Doris MK, Rubeaux M, Pawade T, Otaki Y, Xie Y, Li D, et al. Motion-Corrected imaging of the aortic valve with 18 F-NaF PET/CT and PET/MRI: a feasibility study. J Nucl Med [Internet] 2017;58:1811–4. Available from: http://jnm.snmjournals.org/lookup/doi/10.2967/jnumed.117.194597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng T, Wang J, Fung G, Tsui B. Non-rigid dual respiratory and cardiac motion correction methods after , during , and before image reconstruction for 4D cardiac PET. Phys Med Biol IOP Publishing; 2015;151:151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.