Abstract

Objective:

Define chronic HBV phenotypes in a large, cohort of US and Canadian children utilizing recently published population-based upper limit of normal alanine aminotransferase levels (ULN ALT), compared to local laboratory ULN; identify relationships with host and viral factors.

Background:

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection has been characterized by phases or phenotypes, possibly associated with prognosis and indications for therapy.

Methods:

Baseline enrollment data of children in the Hepatitis B Research Network were examined. Phenotype definitions were; inactive carrier: HBeAg negative with low HBV DNA and normal ALT levels; immune tolerant: HBeAg positive with high HBV DNA but normal ALT levels; or chronic hepatitis B: HBeAg-positive or -negative with high HBV DNA and abnormal ALT levels.

Results:

371 participants were analyzed of whom 274 were HBeAg-positive (74%). Younger participants were more likely be HBeAg-positive with higher HBV DNA levels. If local laboratory ULN ALT levels were used, 35% were assigned the immune tolerant phenotype, but if updated ULN were applied, only 12% could be so defined, and the remaining 82% would be considered to have chronic hepatitis B. Among HBeAg-negative participants, only 21 (22%) were defined as inactive carriers and 14 (14%) as HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B; the majority (61%) had abnormal ALT and low levels of HBV DNA, thus having an indeterminant phenotype. Increasing age was associated with smaller proportions of HBeAg-positive infection.

Conclusions:

Among children with chronic HBV infection living in North America, the immune tolerant phenotype is uncommon and HBeAg positivity decreases with age.

Introduction

Individuals with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection vary considerably in activity and severity of their liver disease and its accompanying levels of viral antigens and HBV DNA (1 – 2). A clear understanding of serologic and biochemical characteristics of HBV-infected individuals is useful in understanding prognosis and need for treatment (1, 3) Chronic infection with HBV occurs much more commonly among children infected in infancy vs in adulthood. (4, 5, 6). Infection during childhood often leads to a prolonged period of “immune tolerance” characterized by minimal or no liver injury despite presence of high viral levels and can be followed by periods of active disease (7). Subjects with immune active disease may require antiviral treatment and some may develop progressive hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis (8). Other individuals ultimately experience transition to an inactive carrier state.”

. These general concepts about the natural history of chronic HBV infection are widely held, but the scientific evidence for their accuracy is not well-defined (9). In particular, the definition and concept of the immune tolerant state is currently in flux and under discussion at the international level (10.)

The Hepatitis B Research Network (HBRN) was established in 2008 and has enrolled a large number of HBV infected participants, including both children and adults (9). HBRN has recently described the diagnostic criteria and frequencies of the various phases of HBV infection or “phenotypes” in adults (3). This previous study found that among adults with HBV infection, 4% were immune tolerant, 36% had immune active hepatitis B (19% HBeAg-positive and 17% HBeAg-negative) while 23% were inactive carriers. A novel finding was that the large proportion of adult participants had serologic and biochemical characteristics that did not allow them to be classified as fitting into any of the four established phenotypes – instead they were referred to as being indeterminant (38%).

Because of the importance of HBV infection occurring during childhood we examined the frequencies of HBV phenotypes among children up to age 18 years enrolled in the HBRN comparing the rates to previous findings in adults. Complicating any analysis of the natural history and clinical phenotyping of chronic HBV infection is the lack of universally accepted definitions for high vs low levels of HBV DNA. A special problem in children has been determining what cutoffs should be used to distinguish “normal” from raised serum aminotransferase levels.

Methods

Human subjects

The HBRN includes six pediatric clinical sites in the US and one in Canada, as previously described (10). Criteria for enrollment in the pediatric cohort of the HBRN are listed in Supplemental Digital Content 1. The pediatric cohort protocol was approved by each Institutional Review Board at the site of enrollment. No subject was enrolled until parents/caregivers signed informed consent and, according to the practice of the institution, children >12 years of age signed assent. The overall design and the specific clinical protocols used by the HBRN were also reviewed and approved by a Data Safety and Monitoring Board, specifically developed by the NIDDK for the HBRN and which also oversaw the quality of the data collection and analysis.

Clinical and laboratory data

All laboratory tests obtained are listed in Supplemental Digital Content 2.

Determination of phenotypes

The baseline enrollment data of participants (ALT, HBeAg and HBV DNA) were used to categorize the participants in regard to clinical-virologic phenotype. Another follow up set of ALT and HBV DNA values was obtained from a subsequent visit between 4-80 weeks after the baseline visit. Phenotype definitions are given in Supplemental Digital Content 3. Previous studies in this cohort, and from the literature, were used to define the HBV DNA cut off for the phenotypes (3).

Two different definitions were used to define normal versus raised ALT levels: [1] locally defined ULN as determined by the local laboratory used at each institution and [2] values established recently in population based studies (updated pediatric reference ranges) (12, 13).These values are listed in Supplemental Digital Content 4. These new updated pediatric reference ranges for ULN serum ALT were used to determine phenotypes, which were compared to phenotypes determined from site-specific values. Determination of short-term phenotype change was made by examining the ALT and HBV DNA data from the next visit for each subject occurring between 4 and 80 weeks after the initial determination (mean and median of 32.9 and 27.9 weeks, respectively, and an interquartile range between 24.1 and 47.4 weeks; for HBeAg positive participants, mean and median of 31.0 and 27.6 weeks, respectively, and an interquartile range between 21.9 and 40.0 weeks; and for HBeAg negative participants, mean and median of 38.8 and 32.7 weeks, respectively, and an interquartile range between 26.6 and 53.0 weeks). Note that the minimum of 4 weeks was selected since this was the earliest interval at which participants were followed.

Statistical methods

Proportions were compared with chi square tests or Fisher’s Exact tests, as appropriate, and distributions of variables in a continuous scale were compared by non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests. Multinomial logistic regression models were used to compare nominal phenotype categories across ordinal age groups. Spearman correlations were used to describe possible associations between ALT and HBV DNA.

Results

The Clinical Cohort

As of July 1 2017, 6.5 years after initiation of the HBRN cohort study, 371 of the 443 children enrolled in the study had adequate baseline data to calculate an HBV phenotype (Supplemental Digital Content 5). The duration of infection could only be known with certainty for those children who were vertically infected )(76% of the whole group, which includes 77 with unknown route of infection). The average age of those 283 children was 10 years which would equate to the duration of infection. All 371 participants were HBsAg-positive and 274 (74%) were seropositive for HBeAg. Of the 97 HBeAg-negative children, 93 had anti-HBe test results available within the previous two years, of whom 90 (97%) were positive. Among the 294 children for whom the mode of infection was known, only 11(4%) had a mode other than vertical. This breakdown was not statistically associated with phenotype; p=0.28 by exact chi-square test. Comparison of HBeAg-negative and HBeAg-positive children is shown in the Table.

Table.

Comparison of selected demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics Between HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative children

| Demographic, biochemical and viral features |

HBeAg positive N=274 |

HBeAg negative N=97 |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs), median | 9.8 | 13.0 | <.0001k |

| Gender | 39% | 53% | .02c |

| Male | 39% | 53% | |

| Race | <.0001c | ||

| White | 4% | 24% | |

| Black | 9% | 21% | |

| Asian | 85% | 53% | |

| Other | 3% | 2% | |

| Continent of birth | <.0001c | ||

| Africa | 7% | 18% | |

| Asia | 61% | 46% | |

| Europe | 2% | 18% | |

| North America | 30% | 19% | |

| Adopted | 53% | 46% | .30c |

| BMI-for-age percentile, median | 58.2 | 53.7 | .69k |

| HBV Genotype | n=235 | n=65 | <.0001c |

| A | 5% | 6% | |

| B | 47% | 17% | |

| C | 34% | 20% | |

| D | 11% | 42% | |

| Other | 4% | 15% | |

| ALT (U/L), Median (range) | 42 | 35 | <.0001k |

| All | (13-2067) | (8-121) | |

| Male | 47 (13-2067) | 37 (15-121) | .0003k |

| Female | 41 (13-1364) | 32 (8-75) | .0007k |

| HBV DNA (log10 IU/mL) | 8.23 | 2.55 | <.0001k |

| Median (range) | (3.53-ALQ†) | (BLQ‡-8.49) | |

| qHBsAg (IU/mL) | n=168 | n=60 | <.0001k |

| Median (range) | 48,910 | 7,559 | |

| (8-338,400) | (1-52,657) | ||

| qHBeAg (IU/mL) | n=174 | N/A | |

| Median (range) | 1,562 | ||

| (1-6,658) | |||

| Platelets (x103/μL) | n=243 | n=81 | .33k |

| Median (range) | 269 | 260 | |

| (135-582) | (121-605) |

non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test

chi-square test

Abbreviations: ALQ, above limit of quantification; BLQ, below limit of quantification; qHBsAg, quantitative HBsAg levels; qHBeAg, quantitative HBeAg levels

Phenotypes of HBeAg-positive children

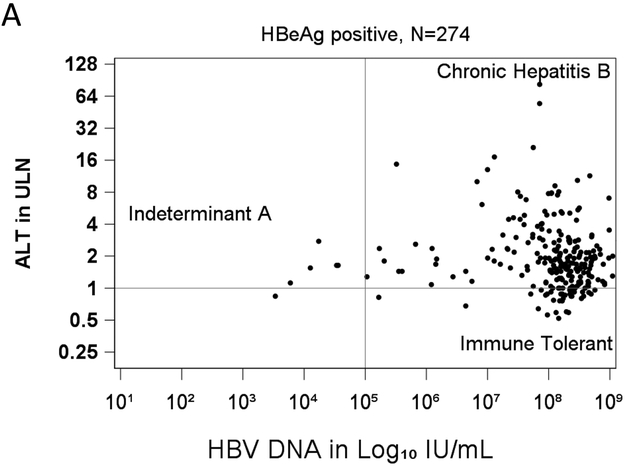

Levels of HBV DNA and ALT values (in multiples of ULN using the updated reference range) for each of the HBeAg-positive children are plotted in Figure 1a. Serum HBV DNA and ALT levels were usually high. But overall, there were no significant associations between serum levels of HBV DNA and ALT (rs = −0.07; p = 0.23).

Figure 1.

Scatterplots of serum HBV DNA vs ALT levels for each subject. The horizontal line shows the cut point for normal vs. raised ALT, and the vertical line the cut points for high vs low HBV DNA. a. ALT and HBV levels for 274 HBeAg-positive children, classifying those with chronic HBeAg-positive hepatitis B, immune tolerant or indeterminant HBV infection. b. ALT and HBV DNA levels for 97 HBeAg-negative children, classifying those with chronic HBeAg-negative hepatitis B, inactive carriers and indeterminants.

Among HBeAg-positive children, most fell into the category of having chronic hepatitis B (225= 82%) and only a minority into the immune tolerant phenotype (n=43: 16%). The remaining six (2%) children had low serum levels of HBV DNA and were designated indeterminant A.

Clinical and laboratory features of the immune tolerant and chronic hepatitis B children are compared in Supplemental Digital Content 6. The two groups were similar in age but the immune tolerant group was more frequently female, infected with genotypes B and C, and almost exclusively Asian. Interestingly, none of 10 white children and only 1 of 24 black children were classified as immune tolerant. Similarly, none of the 11 participants infected with HBV genotype A or the 26 with genotype D were classified as immune tolerant. The only immune tolerant child who was non-Asian and non-infected with genotypes B or C, was an African-born adolescent with genotype E .Strikingly, other viral markers were not different between the two main HBeAg-positive phenotype cohorts. Thus, children with immune tolerant and immune active hepatitis B had similar levels of HBV DNA, HBsAg, and HBeAg.

The HBeAg-positive phenotypes were relatively durable in the short term, 80% of immune tolerant and 86% of those with immune active chronic hepatitis B fit the same phenotype on their next study visit. All the indeterminant A assigned children remained in that category.

HBeAg-negative HBV Phenotypes

Plots of serum HBV DNA levels and ALT values for each of the 97 HBeAg-negative children (Figure 1b) demonstrated that serum HBV DNA levels were usually low, 82% being less than 104 and only 2% above 107 IU/ml. In contrast, ALT levels were mostly elevated (75%) but generally in the range of >1 to 4 times ULN (73%). Overall, there were no significant association between the levels of HBV DNA and ALT (rs = 0.11; p = 0.26). Among HBeAg-negative children, only 14 (14%) could be characterized as having HBeAg-negative, immune active chronic hepatitis B while 21 (22%) had the inactive carrier phenotype. Indeed, the majority of children were assigned an “indeterminant B” phenotype (n=59, 61%), and a few as “indeterminant C” (n=3, 3%),

Selected demographic, clinical and laboratory features of children with the most common HBeAg-negative phenotypes shown in Supplemental Digital Content 7. There were no significant differences among the three phenotypes. Direct comparison of the inactive carriers and HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis B children showed that HBV DNA levels were higher in the immune active group, but this factor was a component of the definitions of both. HBsAg concentrations were also higher in the immune active compared to the inactive carrier group, as might be expected. The indeterminant B group was the largest group. Children in this group tended to have serum levels of HBsAg more typical of immune active disease. While all had elevated serum ALT activities, these were generally mild with none more than 3.0 times the ULN. There was no association between ALT and HBV DNA levels in the indeterminate B participants, although median ALT levels were lower than those in the immune active groups (37 vs 48 U/L, p = 0.0003.) The short-term durability of the 3 common HBeAg-negative phenotypes was comparable although somewhat lower than in the HBeAg-positive phenotypes. Thus, 67% of inactive carriers, 67% of immune active and 77% of indeterminant B children continued to fit their assigned phenotype on their next clinic visit.

HBV Phenotype by age and HBV genotype.

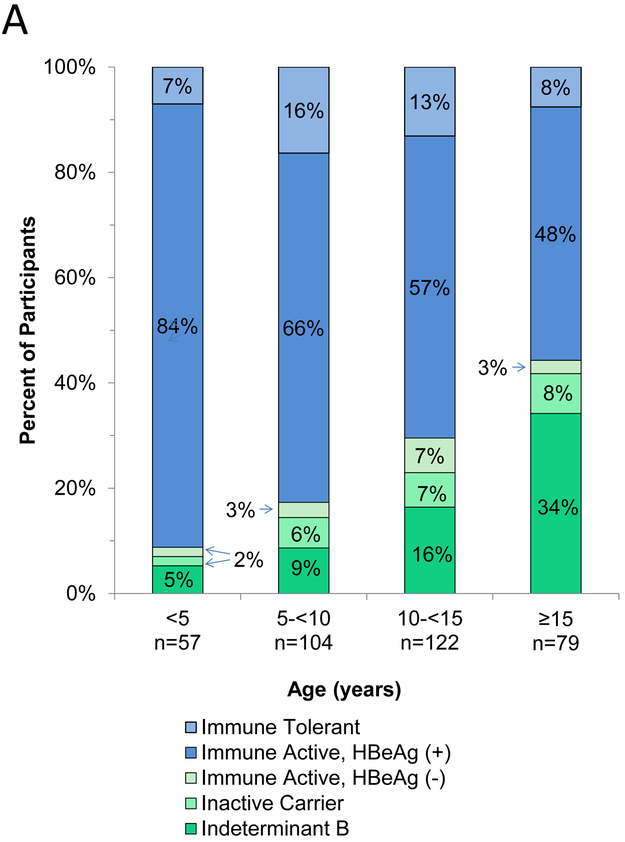

The percentages of children with one of the four typical as well as the indeterminant B phenotypes are shown by age in Figure 2a. Below the age of 5 years, the majority of children were HBeAg positive) and the immune tolerant phenotype accounted for only 7% of children. With increasing age, the percentage of children with HBeAg declined. The majority of participants with HBeAg had immune active chronic hepatitis B regardless of age, while the immune tolerant phenotype accounted for only 7% to 16% of children. The percentage of children without HBeAg increased with age, but the change was largely due to an increase in indeterminant B (low HBV DNA with elevated ALT) with the percentage of HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis B cases remaining low, ranging from 2 to 7%. The four age groups differed significantly and in a linear fashion for frequency of HBeAg (p<0.0001) but the percentage of phenotypes within HBeAg status did not differ by age groups (p=0.45 among HBeAg-positive and p=0.18 among HBeAg-negative children; multinomial logistic regression models).

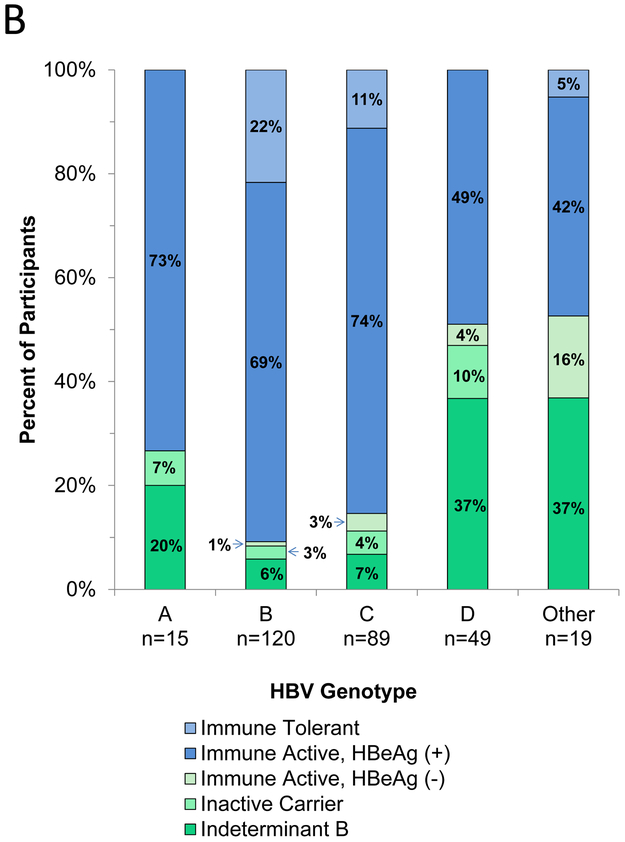

Figure 2.

a. Distribution of HBV phenotypes by age groups

b. Distribution of HBV phenotypes by genotype

The percentages of participants with various clinical phenotypes also varied by HBV genotype, with HBeAg positivity and chronic HBeAg positive hepatitis B being more frequent in children with genotypes B and C (Figure 2b). HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B was most frequent in patients with genotype D. However, among HBeAg negative children, the percentages of patients with each phenotype was similar across the four major genotypes (p=0.73).

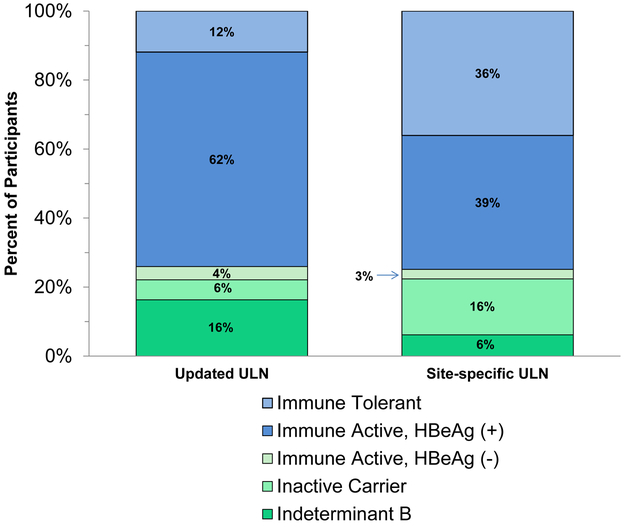

HBV Phenotype by criteria for ALT upper limit of normal (ULN):

The percentages of children in each of four typical clinical phenotypes and indeterminant categories are shown in Figure 3 using the two different standards for the ULN of ALT. Use of the site-specific ranges for normal ALT resulted in 3-fold higher rates of the immune tolerant (35% vs 12%) and inactive carrier state phenotypes (16% vs 6%) and proportionally lower rates of HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B (37% vs 61%) as well as indeterminant B (6% vs 16%) compared to the distribution of phenotypes using the updated reference standards.

Figure 3.

Distribution of HBV phenotypes using two different reference standards for upper limits of the normal range.

Discussion

The multicenter, longitudinal pediatric cohort of the HBRN provides a unique opportunity to study the progression of chronic HBV infection in well-characterized children. The analysis shown here represents a cross-sectional study of the participants at the time of enrollment. The striking findings were: [1] the frequency of HBeAg-positivity decreases with age, [2] the immune tolerant phenotype is uncommon; [3] most HBeAg-positive children have immune active, chronic hepatitis B; and [4] indeterminant phenotypes are frequent among HBeAg-negative children. While HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B was the single most frequent phenotype identified (61%), ALT elevations were usually mild, most children having values less than 3 times ULN. Nevertheless, these results suggest that a higher proportion of children perhaps qualify to receive antiviral therapy than previously believed. These patterns were clearly accentuated by the use of the updated reference range for serum ALT levels in children. Thus, the proportion of the immune tolerant phenotype would be three times as high as reported here if site-specific ULN values were used, and the relative proportion of HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B would be similarly reduced. The findings of this study are consistent with previous findings among adults in the HBRN Cohort study, which found that the immune tolerant phenotype was uncommon and that a large proportion of adults did not fit into one of the usual or typical phenotype groups and many therefore had “indeterminant” forms of hepatitis B (3).

The immune tolerant phenotype has been described as the initial stage of HBV infection particularly in children. The literature on HBV in children most often describes Asian children and states that the majority are HBeAg-positive and in the immune tolerant phenotype (16). The majority of children in our HBRN cohort are also HBeAg positive but the results here suggest that, using the updated reference ranges for ALT, only a fraction of children have the immune tolerant phenotype and it occurs largely in Asian children with genotypes B or C. The immune tolerant phenotype is 12% of the whole group, 15% among Asian and 1% among non-Asian children. Even using site specific ULN, the % of HBeAg-positive children in immune tolerant phase was still low, 35% overall, 40% in Asian and 18% in non-Asian children. Furthermore, the small percentage of children with this phenotype remained relatively constant during short-term follow up within each age group. Only careful, prospective follow up on these children can begin to address the issue of whether the immune tolerant state is a transient early phase of chronic HBV infection in children or whether it arises at different ages and times during the course of prolonged infection.

Accurate determination whether a child is in the immune tolerant or active phase is important, both for the individual child and at the population level in designing clinical trials and in making recommendations for treatment. However it should be noted that in general, children with ALT values in the “normal or near normal” range do not respond as well to antiviral therapy as those with markedly elevated ALT(17)(18)..Of interest, a recent report by Zhu et al of a clinical trial of immunetolerant children (baseline mean ALT 45 U/L) showed increasing virologic responses from ALT of 20 to 80 U/L (19).

Overall, 26% of children were HBeAg negative. This study included a wide age range of children. It is known that spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion is rare in children and begins to increase in teenage years (10). When stratified by age, 15%of children <10 years and 35% of those >10 years were HBeAg negative. By race, 18% of Asian and 52% of non-Asians were HBeAg negative.

The large percentage of HBeAg-negative children with hepatitis B who had the Indeterminate B phenotype was somewhat unexpected. We acknowledge that this phenotype seemed to result from using the updated reference ranges for ALT. Patients with the indeterminate B phenotype had levels of HBV DNA that resembled inactive carriers, but raised serum ALT values as occurs in HBeAg-negative immune active disease, 15% had an ALT >2x updated ULN ALT, and 73% had HBV DNA <103IU/mL. The question is whether they are inactive carriers of hepatitis B who have ALT elevations for other reasons, such as fatty liver disease (14, 15) or an adverse effect of a medication or whether they have chronic hepatitis B with fluctuating levels of HBV DNA and may develop progressive liver disease. Fatty liver disease seems an unlikely explanation. Overall there was no difference in BMI between those HBeAg-negative children in the indeterminate B phenotype vs other phenotypes. Only 8% had a BMI in the obese range (≥95th percentile). The relatively low proportion of obese children in our cohort compared to the North American pediatric population is probably explained by the large proportion of Asians in our study. However given that obesity comorbidities and non-obese fatty liver disease may occur disproportionately in Asians in comparison to other ethnicities it is possible that our Asian cohort is more likely to have NASH at a lower BMI compared to other ethnicities (20) (21)

Serum levels of HBsAg may be helpful in identifying the inactive carrier state, but many of the indeterminant B children had HBsAg levels higher than were typically found in inactive carriers. Finally, those in the indeterminant B group may have mild chronic hepatitis B despite the low apparent level of viral replication. Only careful follow up of these children will resolve this conundrum and help determine whether treatment is indicated.

The strengths of this study were the large numbers of patients enrolled, their diversity of race and country of birth, and the wide range of apparent disease severity. In addition, a central virology laboratory was used to measure HBV markers including sensitive tests for quantitative levels of HBsAg, HBeAg and HBV DNA. The study was a cross-sectional analysis of viral and biochemical factors associated with hepatitis B and represents the starting point of a prospective study of the course of the infection. The weaknesses of the study were that it was not population-based but dependent on patient referral. Furthermore, only children who had not already started antiviral therapy were enrolled, so that children with more active liver disease may have been underrepresented. In addition, the phenotype assignments were based upon a recent update of the presumed normal reference ranges for ALT values, which may not be appropriate to apply to both boys and girls of different races. Liver biopsies or other non-invasive tests of liver disease such as transient elastography were not done as a routine to establish the presence or absence of active disease. Nevertheless, study of this large cohort represents an important step in attempting to better define the natural history of chronic HBV infection in children with which to begin to assess the use of current antiviral therapies in this challenging disease.

In summary, the major findings reported here were that most children with chronic HBV infection in this cohort residing in North America who were not receiving antiviral therapy, had immune active disease; that the immune tolerant phenotype was uncommon and seen largely in Asian children infected with genotypes B and C; that HBeAg-positivity decreased with age; and that the majority of HBeAg-negative children fell into a novel, indeterminant phenotype. We acknowledge that our phenotype classification is sensitive to the use of updated pediatric reference ranges for ALT and long-term follow up is necessary to resolve whether these children have active disease that merits treatment. The clinical implications of our findings are that pediatric gastroenterologists should apply these population-based updated pediatric reference ranges for ALT in their clinical practice, that they should consider closer follow up for their patients with HBV and immune active disease (such as twice yearly labs and yearly determination of non-invasive biomarkers and imaging for liver fibrosis when these become validated for children with HBV). Designers of clinical trials of antiviral agents for pediatric patients with HBV should consider including all children with immune active disease. However we do not yet have enough information to recommend using the new ALT norms for treatment decisions in routine clinical care.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Criteria for enrollment in the HBRN Pediatric Cohort

Supplemental Digital Content 2 Clinical and laboratory data

Supplemental Digital Content 3 Definition of phenotypes of Chronic HBV Infection

Supplemental Digital Content 4 Definitions of Upper Limit of the Normal Range for Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT)

Supplemental Digital Content 5 Consort diagram of development of the study cohort

What is known

Subjects with Hepatitis B Virus infection can be categorized according to clinical phenotypes

It has been thought that a large number of children with HBV are “immunetolerant”, the phenotype that responds poorly to antiviral treatment

What is new

Our data from this large North American cohort of children with HBVanalyzed with updated pediatric reference ranges for alanine aminotransferase demonstrate that only a small proportion are immunetolerant

A higher proportion of children with HBV than previously believed may qualify for antiviral treatment although prospective studies and clinical trials will be necessary before firm conclusions can be drawn

Acknowledgments

Funding: The Hepatitis B Research Network was funded as a series of cooperative agreements [U01s] by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK): U01 DK082916 [to Kathleen Schwarz; PIs: Karen Murray and Norberto Rodriguez-Baez]; U01 DK082864 [to Steven Belle]; U01 DK082874 [Harry Janssen; PI: Simon Ling]; U01 DK082944 [to Norah Terrault; PI: Philip Rosenthal]; U01 DK082843 [to Lewis R. Roberts; PI: Sarah Jane Schwarzenberg], U01 DK082871 [to Adrian Di Bisceglie; PI: Jeffery Teckman]. Addition support was provided by an interagency agreement between NIDDK and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: A DK-3002-001 [to Lilia Milkova Ganova-Raeva]) and via the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH via CTSA grants: UL1 TR000423 [to Kathleen Schwarz] and UL1 TR000004 [to Norah Terrault]), and by Roche Molecular Systems via a CRADA through the NIDDK.

Abbreviations:

- (HBV)

Hepatitis B virus

- (HBRN)

Hepatitis B Research Network

- (ALT)

Alanine aminotransferase

- (AST)

Aspartate aminotransferase

- (ULN)

Upper limit of normal

- (NIDDK)

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Appendix

Members of Hepatitis B Research not listed as authors include the following: Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD): Hongxia Li, MBBS, MS, Douglas Mogul, MD, Robert Anders, MD, PhD Kim Kafka, RN; Minnesota Alliance for Research in Chronic Hepatitis B Consortium (Minneapolis, MN): Shannon M. Riggs, LPN, AS; Midwest Hepatitis B Consortium (Cardinal Glennon Children’s Medical Center, Saint Louis University, Saint Louis, MO): Rosemary Nagy, RD MBA, Jacki Cerkoski, RN MSN; University of Toronto Consortium (The Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada): Caitlin Yuan, BSc, MSc, Rosemary Swan, BN, Constance O’Connor, MN; HBV CRN North Texas Consortium (University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, TX): Laurie A. Rodgers-Augustyniak, RN, Shirley Montanye, RN; San Francisco Hepatitis B Research Group Consortium (University of California, San Francisco, CA): Shannon Fleck, BS, Camille Langlois, MS; PNW/Alaska Clinical Center Consortium (University of Washington, Seattle, WA): Kara L. Cooper. Data Coordinating Center (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA): Michelle Danielson, PhD, Tamara Haller, Geoffrey Johnson, MS, Stephanie Kelley, MS, Sharon Lawlor, MBA, Ruosha Li, PhD.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

KB Schwarz has research grants from Gilead, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche/Genentech and consults for Gilead, Roche/Genentech and Up to Date

Adrian M Di Bisceglie has research grants from Gilead and serves on advisory boards to Gilead and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Karen F Murray has research grants supported by Gilead, Merck, Shire, and owns stock in Merck

Philip Rosenthal has research grants from Abbvie, Gilead, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche/Genentech and consults for Gilead, Abbvie, Intercept, Alexion, Retrophil, Albireo, Audentes and Mirum.

Simon C Ling receives research funding from Abbvie and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Norberto Rodriguez-Baez has research grants supported by Gilead.

Jeffrey Teckman has research grants from Gilead, Alnylam Inc., Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals and Dicerna Inc., and consultant relationships with BioMarin, Editas, Proteostasis and Retrophin.

Yona Keich Cloonan, Manuel Lombardero, Sarah Jane Schwarzenberg and Jay H Hoofnagle have no duality or conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, et al. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 2018;67:1560–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Bisceglie AM, Lombardero M, Teckman J, et al. Determination of hepatitis B phenotype using biochemical and serological markers. J Viral Hepat. 2017;24:320–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tong MJ, Trieu J. Hepatitis B inactive carriers: clinical course and outcomes. J Dig Dis. 2013;14:311–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wirth S, Bortolotti F, Brunert C, et al. Hepatitis B virus genotype change in children is closely related to HBeAg/anti-HBe seroconversion. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;57:363–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sokal EM, Paganelli M, Wirth S, et al. Management of chronic hepatitis B in childhood: ESPGHAN clinical practice guidelines: consensus of an expert panel on behalf of the European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Hepatol. 2013;59:814–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haber BA, Block JM, Jonas MM, et al. Recommendations for screening, monitoring, and referral of pediatric chronic hepatitis B. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e1007–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jonas MM, Block JM, Haber BA, et al. Treatment of children with chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: patient selection and therapeutic options. Hepatology. 2010;52:2192–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghany MG, Perrillo R, Li R, et al. Characteristics of adults in the hepatitis B research network in North America reflect their country of origin and hepatitis B virus genotype. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:183–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong G Management of chronic hepatitis B patients in immunetolerant phase: what latest guidelines recommend.Clin Mol Hepatol. 2018. June;24:108–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwarz KB, Cloonan YK, Ling SC, et al. Children with Chronic Hepatitis B in the United States and Canada. J Pediatr. 2015;167:1287–94.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganova-Raeva L, Ramachandran S, Honisch C, et al. , Robust hepatitis B virus genotyping by mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:4161–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colantonio DA, Kyriakopoulou L, Chan MK, et al. Closing the gaps in pediatric laboratory reference intervals: a CALIPER database of 40 biochemical markers in a healthy and multiethnic population of children. Clin Chem. 2012;58:854–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwimmer JB, Dunn W, Norman GJ, et al. SAFETY study: alanine aminotransferase cutoff values are set too high for reliable detection of pediatric chronic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1357–64, 64.e1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loomba R Serum alanine aminotransferase as a biomarker of treatment response in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1731–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoofnagle JH, Van Natta ML, Kleiner DE, et al. Vitamin E and changes in serum alanine aminotransferase levels in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:134–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jonas MM, Mizerski J, Badia IB et al. Clinical trial of lamivudine in children with chronic hepatitis B. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002; 346: 1706–1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenthal P, Ling SC, Belle SH, et al. ; Hepatitis B Research Network (HBRN).Combination of Entecavir/Peginterferon Alfa-2a in Children With Hepatitis B e Antigen-Positive Immune Tolerant Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection. Hepatology. 2018. October 15. doi: 10.1002/hep.30312. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu S, Zhang H, Dong Y, et al. ntiviral therapy in hepatitis B virus-infected children with immune-tolerant characteristics: A pilot open-label randomized study. 2018 J Hepatol. Jun;68(6):1123–1128.. Epub 2018. February 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim D, Kim WH. Nonobese Fatty Liver Disease.. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2017) ;15(4):474–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang D, Li Y, Lee SG, et al. Ethnic differences in body composition and obesity related risk factors: study in Chinese and white males living in China. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019835. Epub 2011 May 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Criteria for enrollment in the HBRN Pediatric Cohort

Supplemental Digital Content 2 Clinical and laboratory data

Supplemental Digital Content 3 Definition of phenotypes of Chronic HBV Infection

Supplemental Digital Content 4 Definitions of Upper Limit of the Normal Range for Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT)

Supplemental Digital Content 5 Consort diagram of development of the study cohort