Health care teams can create gender-affirming patient experiences for transgender men and gender-diverse people in and around pregnancy through advancing changes in perinatal health care settings.

BACKGROUND:

Little is documented about the experiences of pregnancy for transgender and gender-diverse individuals. There is scant clinical guidance for providing prepregnancy, prenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum care to transgender and gender-diverse people who desire pregnancy.

CASE:

Our team provided perinatal care to a 20-year-old transgender man, which prompted collaborative advocacy for health care systems change to create gender-affirming patient experiences in the perinatal health care setting.

CONCLUSION:

Systems-level and interpersonal-level interventions were adopted to create gender-affirming and inclusive care in and around pregnancy. Basic practices to mitigate stigma and promote gender-affirming care include staff trainings and query and use of appropriate name and pronouns in patient interactions and medical documentation. Various factors are important to consider regarding testosterone therapy for transgender individuals desiring pregnancy.

Teaching Points

Testosterone should not be considered a contraceptive. Testosterone may lead to amenorrhea and cessation of ovulation. However, although testosterone may reduce fertility, fertilization is possible despite prior or active use of testosterone and while amenorrheic from testosterone use.

Testosterone is not currently recommended during pregnancy owing to possible irreversible fetal androgenic effects. An optimal interval between discontinuing testosterone and conceiving is unknown at this time.

Although transgender and gender-diverse people previously on testosterone may adjust well to pregnancy, lack of testosterone use during fertilization and pregnancy may lead to or exacerbate gender dysphoria.

Testosterone may be excreted in small quantities in human milk and may affect milk production. Currently, it is not recommended to use testosterone while chestfeeding, until more information is known about the effects of testosterone use on human milk.

Pregnancy in transgender men and other gender-diverse people who were assigned female sex at birth is an experience that has gained visibility in medical literature over the past decade.1–3 Gender-affirming treatment for transgender and gender-diverse people may include psychosocial support, hormone therapy, surgery, and other interventions aimed at aligning their bodies and daily physical experiences with their gender identities.4,5 Common gender-affirming treatments for transgender people include testosterone, chest binding, and masculinizing chest surgery.5 Although some gender-affirming treatments such as hysterectomy or oophorectomy eliminate fertility, transgender men may retain or desire reproductive capacity, even in the case of prior testosterone use.2 Studies indicate that transgender people have experienced pregnancy after undergoing gender-affirming processes and treatments (be it social, medical, or surgical), and some desire future pregnancy.3,6,7 Only 8% of transgender people who were assigned female sex at birth have undergone hysterectomy, many engage in sexual activity that could result in pregnancy, and there is evidence to support that there is an unmet contraceptive need in this community.6,8,9 Studies indicate that transgender people have experienced intended and unintended pregnancy after undergoing gender-affirming processes and treatments, and many desire future pregnancy and parenthood at different ages and stages of transition.3,7,10,11 For transgender and gender-diverse people who desire pregnancy, there is little clinical guidance for fertilization and prenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum care.

Given the dearth of perinatal guidance for transgender and gender-diverse people, we share our experience caring for a transgender man during his pregnancy. With the goal of creating an inclusive, compassionate, and equitable health care experience for him and his partner and other gender-diverse people, the team worked in collaboration with multiple stakeholders throughout the health care system to create new systems and transform existing systems to assure patient-centered care.

CASE

The patient is a 20-year-old healthy transgender man who initiated gender-affirming testosterone therapy with his primary care physician 5 months before pregnancy. Before starting testosterone therapy, he was clear that he desired the option of future pregnancy and had not undergone any other gender-affirming medical or surgical treatments. He was counseled on contraceptive and fertility-preservation options and the risks and benefits of testosterone therapy. His gender nonbinary partner was assigned male sex at birth and was living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). They received standard care for a serodifferent couple during pregnancy, including the use of preexposure prophylaxis for the patient as well as coordination and support for his partner to maintain a consistently undetectable HIV viral load to reduce the risk of sexual HIV transmission within the couple.

The patient's primary care physician sought advice on testosterone use in pregnancy through consultation with TransLine,12 an expert clinical consultation service, which recommended stopping testosterone before fertilization given the potential androgenic effects of testosterone on a developing fetus. After consultation, the patient subsequently decided to discontinue testosterone therapy while attempting pregnancy. Two months after discontinuing testosterone therapy, the patient achieved pregnancy through penis-in-vagina intercourse. He was referred to San Francisco General Hospital's multidisciplinary perinatal HIV care team for prenatal care at 7 weeks of gestation.

During prenatal visits, the patient was asked preferred terminology for anatomic parts and functions (some transgender men prefer terms such as frontal pelvic opening) (Klein A, Golub SA. Sexual healthcare experiences and needs among a national sample of transgender men and non-binary individuals [abstract]. Ann Behav Med 2018;52:S614.)13; his preference was medical terminology (eg, vagina, uterus). Individual health care provider and systems changes were undertaken to consistently use the patient's correct pronouns—from registration, to intake with medical assistants, to health care provider visits. We notified staff and health care providers of the patient's appropriate gender and pronouns by posting a “clinical alert” in the patient's electronic medical record (EMR) chart. This information was also communicated to the entire care team during preclinic huddles.

Trainings on culturally appropriate care provision for transgender patients were conducted with prenatal clinic and labor and delivery clinical staff. Ultrasonographers were trained to use gender-neutral language and techniques to assure an inclusive and welcoming experience during ultrasound examinations for this patient and all patients who follow. A social worker provided intensive case management and psychosocial support, including assisting in aligning the patient’s identity documents with his affirmed gender, and confirmed with the hospital’s birth certificate office that the patient and his partner could be listed as coparents, including their preferred names and gender identities. Attempts to change the patient's EMR to reflect his gender identity were unsuccessful as a result of technical limitations of distinguishing sex and gender within the EMR system and were further complicated by the inability of the EMR system to register an admission of a nonfemale patient to the labor and delivery floor.

At the end of the second trimester, the patient and his care team began proactively discussing future fertility, contraception, and options for resuming gender-affirming testosterone therapy postpartum. He expressed a desire to restart testosterone therapy once he finished chestfeeding (chestfeeding is common gender-neutral term used in the transgender community rather than breastfeeding) and was unsure whether or when he might desire pregnancy again. Given that testosterone therapy likely significantly reduces, but does not eliminate, the chance of pregnancy,14 he decided on a postpartum etonogestrel subcutaneous implant for contraception. Before delivery, the patient and his partner were offered a private tour of the labor and delivery unit as well as labor and chestfeeding preparation workshops by a health educator who had been trained in transgender-inclusive health education.

The patient had an uncomplicated labor and vaginal delivery after spontaneous onset of labor at 40 weeks of gestation. The healthy male newborn had no signs of androgenizing effects from in utero testosterone exposure. The patient's postpartum course was uneventful. He initiated successful chestfeeding immediately postpartum with support from lactation consultants and nursing staff. The patient and infant attended joint postpartum and well-child visits at a family-oriented primary care clinic affiliated with the county hospital with the family physician who also served as his prenatal care provider. At approximately 12 weeks postpartum, the patient discontinued chestfeeding and resumed testosterone therapy.

DISCUSSION

Many transgender and gender-diverse people have the capacity to become pregnant either through sexual intercourse or assistive reproductive interventions.2,6 This case highlights the utility of engaging in discussions pertaining to reproductive autonomy and taking a comprehensive sexual history, including desire for pregnancy and pregnancy prevention, to guide appropriate medical interventions and motivate necessary system changes as part of primary care and supporting gender affirmation.

This case also highlights the need for supporting care providers to access and use information regarding the effect of testosterone on ability to conceive, maintain a healthy pregnancy, have healthy offspring, and chestfeed successfully. In a cross-sectional study of 41 transgender men who became pregnant, 61% reported using testosterone before becoming pregnant and 20% became pregnant while still amenorrheic from testosterone use.2 Transgender and gender-diverse patients who retain a uterus and ovaries may maintain reproductive capacity after initiating testosterone, and testosterone does not always reliably prevent unintended pregnancy.2 There are no well-powered human studies examining the use of exogenous testosterone in pregnancy. It is generally theorized that testosterone may androgenize the fetus based on limited animal models.15 A small study of 147 cisgender women found that increases in levels of endogenous testosterone were negatively correlated to fetal length and weight.16 Lastly, very limited data suggest that increased levels of endogenous testosterone production have been associated with delayed and decreased milk production17,18; though a case study found no adverse effects at 5 months of age on an infant who was breastfed by a mother who received a low-dose (100 mg) subcutaneous testosterone pellet while breastfeeding.19 Currently there are insufficient safety data to recommend the use of testosterone during pregnancy and chestfeeding, and the drug is classified as pregnancy category X by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.20

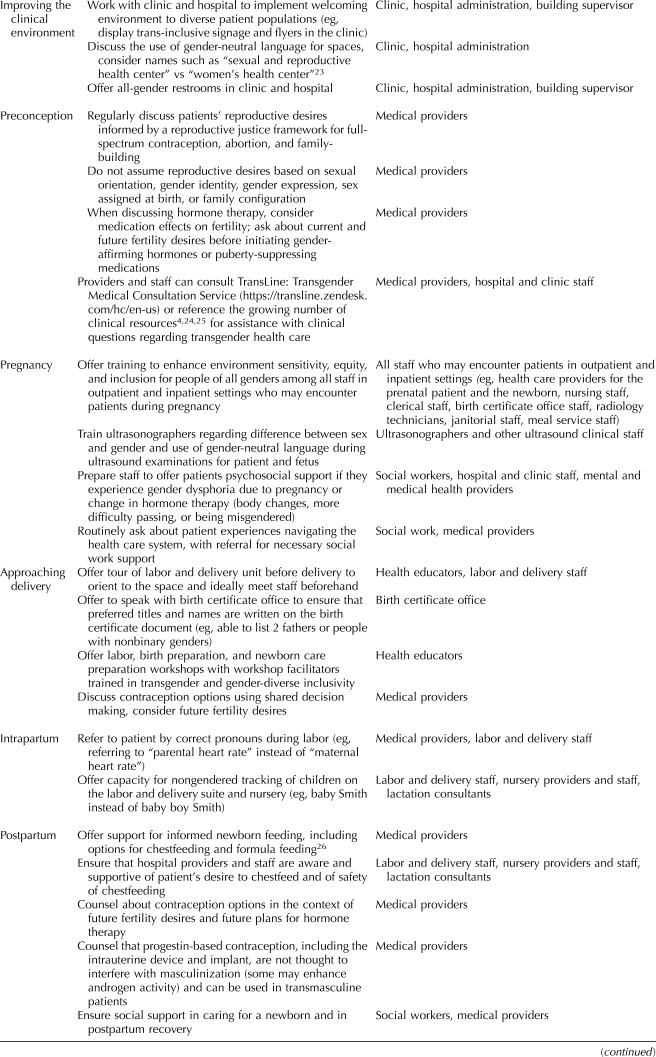

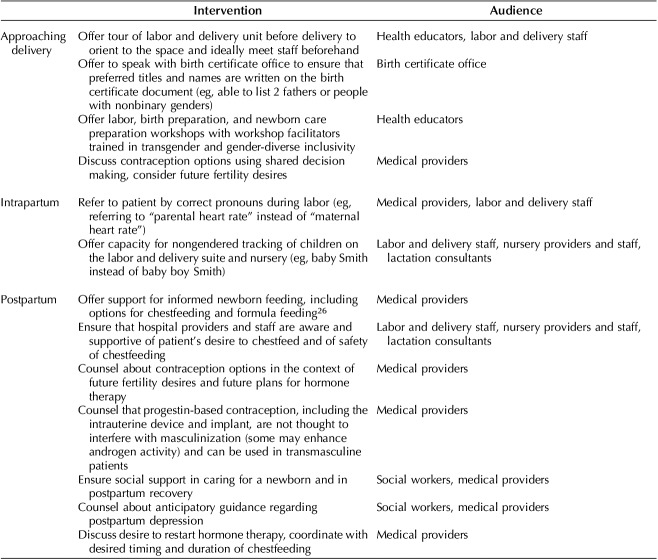

Transgender and gender-diverse individuals routinely face stigma and discrimination navigating the health care system, including gender insensitivity, denial of services, and verbal abuse in medical visits.21 In a national survey, 23% of respondents reported avoiding seeking care owing to fear of mistreatment as a transgender person.21 Prenatal care for transgender men may be further complicated by cultural beliefs of pregnancy as a “woman-only” experience. Feelings of gender dysphoria may be pronounced in the absence of testosterone use during the fertilization and peripartum period.15 Practices to mitigate stigma and promote gender affirmation throughout the perinatal process include staff trainings; query for and use of appropriate names and pronouns in patient interactions and in all documentation, including the EMR and birth certificate; and gender-neutral, transgender-inclusive language for patient care spaces. Please refer to Table 1 for a summary of recommendations.

Table 1.

Recommended Systems-Level and Interpersonal-Level Interventions for Trans-Inclusive Care In and Around Pregnancy

Footnotes

Dr. Obedin-Maliver was partially supported by grant 1K12DK111028 from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Disorders.

Financial Disclosure Dr. Obedin-Maliver was a research consultant on a Society for Family Planning funded grant received by Ibis, an independent non-profit research group, to investigate facilitators and barriers to contraception and abortion among transgender and gender expansive people. She completed those consultation services in March 2018. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

The authors thank the patient for sharing his story and teaching them many valuable lessons in cultural humility, and HIVE social worker Rebecca Schwartz and ZSFG Clinical Nurse Specialist Kelly Brandon for advocating for systems change to improve care for this patient.

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal's requirements for authorship.

Peer reviews and author correspondence are available at http://links.lww.com/AOG/B552.

REFERENCES

- 1.Obedin-Maliver J, Makadon HJ. Transgender men and pregnancy. Obstet Med 2016;9:4–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Light AD, Obedin-Maliver J, Sevelius JM, Kerns JL. Transgender men who experienced pregnancy after female-to-male gender transitioning. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124:1120–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellis SA, Wojnar DM, Pettinato M. Conception, pregnancy, and birth experiences of male and gender variant gestational parents: it’s how we could have a family. J Midwifery Womens Health 2015;60:62–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Center of Excellence for Transgender Health. In: Deutsch MB, editor. Guidelines for the primary and gender-affirming care of transgender and gender nonbinary people. San Francisco, CA: University of California; 2016:199. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reisner SL, Radix A, Deutsch MB. Integrated and gender-affirming transgender clinical care and research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016;72(suppl 3):S235–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cipres D, Seidman D, Cloniger C, Nova C, O’Shea A, Obedin-Maliver J. Contraceptive use and pregnancy intentions among transgender men presenting to a clinic for sex workers and their families in San Francisco. Contraception 2017;95:186–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffkling A, Obedin-Maliver J, Sevelius J. From erasure to opportunity: a qualitative study of the experiences of transgender men around pregnancy and recommendations for providers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17(suppl 2):332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheim AI, Bauer GR. Sex and gender diversity among transgender persons in Ontario, Canada: results from a respondent-driven sampling survey. J Sex Res 2014;52:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The report of the 2015 U.S. transgender survey. Available at: https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf. Retrieved January 21, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wierckx K, Van Caenegem E, Pennings G, Elaut E, Dedecker D, Van de Peer F, et al. Reproductive wish in transsexual men. Hum Reprod 2012;27:483–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen D, Matson M, Macapagal K, Johnson EK, Rosoklija I, Finlayson C, et al. Attitudes toward fertility and reproductive health among transgender and gender-nonconforming adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2018;63:62–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.TransLine: Transgender Medical Consultation Service. Available at: https://transline.zendesk.com/hc/en-us. Retrieved June 10, 2019.

- 13.Potter J, Peitzmeier SM, Bernstein I, Reisner SL, Alizaga NM, Agénor M, et al. Cervical cancer screening for patients on the female-to-male spectrum: a narrative review and guide for clinicians. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:1857–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Light A, Wang LF, Zeymo A, Gomez-Lobo V. Family planning and contraception use in transgender men. Contraception 2018;98:266–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dean A, Smith LB, Macpherson S, Sharpe RM. The effect of dihydrotestosterone exposure during or prior to the masculinization programming window on reproductive development in male and female rats. Int J Androl 2012;35:330–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlsen SM, Jacobsen G, Romundstad P. Maternal testosterone levels during pregnancy are associated with offspring size at birth. Eur J Endocrinol 2006;155:365–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Betzold CM, Hoover KL, Snyder Delayed lactogenesis II: a comparison of four cases. J Midwifery Womens Health 2004;49:132–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoover KL, Barbalinardo LH, Platia MP. Delayed lactogenesis II secondary to gestational ovarian theca lutein cysts in two normal singleton pregnancies. J Hum Lact 2002;18:264–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glaser RL, Newman M, Parsons M, Zava D, Glaser-Garbrick D. Safety of maternal testosterone therapy during breast feeding. Int J Pharm Compd 2009;13:314–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Library of Medicine. LactMed: a TOXNET database: testosterone. Bethesda (MD): National Institutes of Health; 2016. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501721/. Retrieved September 23, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kosenko K, Rintamaki L, Raney S, Maness K. Transgender patient perceptions of stigma in health care contexts. Med Care 2013;51:819–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Transgender Law Center. ID please: a guide to changing California & federal identity documents to match your gender identity. Available at: http://transgenderlawcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/ID_Please_FINAL_7.25.14.pdf. Retrieved November 10, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stroumsa D, Wu JP. Welcoming transgender and nonbinary patients: expanding the language of “women’s health.” Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;219:585.e1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fenway Institute. Available at: https://fenwayhealth.org/the-fenway-institute/. Retrieved November 10, 2018.

- 25.Association of American Medical Colleges. Sexual and Gender Minority Health Resources. AAMC videos and resources. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/diversity/431388/videos.html. Retrieved November 10, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birthing and breast or chestfeeding trans people and allies. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/groups/TransReproductiveSupport/. Retrieved November 10, 2018. [Google Scholar]