Abstract

Intimate partner violence (IPV) and sexual violence (SV) are drivers of women’s morbidity and mortality in urban environments yet remain among the most underreported crimes in the USA. We conducted 26 in-depth interviews with women who experienced past-year IPV or SV, to explore structural and community influences on police contact in Baltimore, MD. Results indicate that gender-based and race-based inequities intersected at the structural and community levels to discourage women from police contact following IPV/SV. Structural influences on police reporting included police discriminatory police misconduct, perceived lack of concern for citizens, power disparities, fear of harm from police, and IPV/SV-related minimization and victim-blaming. Community social norms of police avoidance discouraged police contact, enforced by stringent sanctions. The intersectional lens contextualizes a unique paradox for Black women: the fear of unjust harm to their partners through an overzealous and racially motivated police response and the simultaneous sense of futility in a justice system that may not sufficiently prioritize IPV/SV. This study draws attention to structural race and gender inequities in the urban public safety environment that shape IPV/SV outcomes. Race-based inequity undermines women’s safety and access to justice and pits women’s safety against community priorities of averting police contact and disproportionate incarceration. A social determinants framework is valuable for understanding access to justice for IPV/SV. Enhancing access to justice for IPV/SV requires overcoming deeply entrenched racial discrimination in the justice sector, and historical minimization of violence against women.

Keywords: Intimate partner violence, Sexual violence, Police, Disparities

Background

An estimated 36% of US women have experienced intimate partner violence (IPV), i.e., physical or sexual violence, or stalking by an intimate partner [1], and 21% of women have experienced attempted or completed rape, i.e., sexual violence (SV), by any perpetrator [1]. IPV/SV imparts poor physical, mental, and sexual health [2], and IPV is implicated in over half of homicides to women [3]. Homicide was the second-leading cause of death for Black women aged 15–24 in 2015 [3, 4]. Lifetime IPV prevalence is highest among women of color (Black—44%; multiracial—54%; American Indian/Alaskan Native—46%) relative to White women (35%); this pattern is echoed in SV prevalence [5]. Men and women’s experiences of IPV/SV experiences are distinct. Women’s SV perpetrators are predominantly current or former intimate partners (51.1%) and acquaintances (40.8%), while men’s perpetrators are primarily acquaintances (52.4%) [5]. Women experience IPV at younger ages (age at onset 11–17 years for 22.4% of female survivors vs 15% of male survivors), experience more severe physical violence (24.3% lifetime prevalence for women vs 13.8% for men), and are more likely to experience multiple forms of IPV (43% among female IPV victims vs 8% among male IPV victims) [5]. Current or former intimate partners are implicated in over half of homicides to women (51.4%) relative to 7.9% of those to men [6].

Justice and accountability represent one of three pillars of comprehensive violence prevention and response, in addition to prevention and survivor support [7, 8]. Alarmingly, IPV/SV is among the most underreported violent crimes, with 46% and 65% non-report rates for IPV and SV, respectively, between 2006 and 2010 [9, 10]. Lack of confidence in the justice system increasingly explains non-reporting (20% in 2010 up from 7% in 2005) [10].

Police often represent the most immediate and visible agents of the justice system [11]. Contacting the police for IPV reduces revictimization [11], demonstrating the public health value of effective public safety and justice systems. Enhancing the IPV/SV response requires understanding determinants of police contact. Such inquiry can be approached from a social determinants framework that seeks to understand multiple layers of influence across incident, individual, interpersonal, community, and social/structural factors. Research to date has taken a limited focus on incident, individual, and interpersonal levels of the socio-ecological model. Incident characteristics that prompt reporting include severity, property damage, and use of a weapon [12, 13]. Lack of injury discourages IPV/SV reporting [13], in part via fears of disbelief [14]. Individual determinants of police contact following IPV/SV include awareness and use of IPV/SV support services, medical care, and forensic exams [15, 16]. At the interpersonal level, experiencing violence from a known assailant, including partners, discourages police reporting [13, 14], likely reflecting social or economic dependence [17], and fear of retribution [14, 16]. Perpetrators sometimes engage in direct interference in successful police contact, via physically preventing calls to police, as well as manipulation of police [18].

The structural and community influences on police contact for IPV/SV are far less understood and benefit from an intersectional lens. Intersectionality recognizes that the social identity domains to which a person belongs can interact to create and reinforce oppressions that remain unrecognized should each category be examined individually [19, 20]. Two such intersecting domains of inequity warrant exploration. First, gender discrimination in the response to IPV/SV has been documented, including skepticism, mistrust, and fears and experiences related to gender bias, minimization, undue skepticism, victim-blaming, and sexual shaming, all of which can undermine successful engagement in the criminal and civil justice sectors, and incur retraumatization [18, 21–23]. Historical deprioritization of women’s rights has also been built into policy such as marital exemption for rape [24]. Second, racial/ethnic disparities are evident in experiences and perceptions with the justice system more broadly [25]. The codification of historical racism into policy has led to modern practices that fuel disproportionate incarceration and attendant distrust in the formal justice system, including racial profiling, mandatory minimum prison sentences, cash bail, and inadequate legal defense [26]. Police-related trust, intended cooperation, and institutional support are lower among Blacks and Latinos relative to their White counterparts [27], partially stemming from the historical inequities in the justice system reflected in disparities in Black and Latino arrests, excessive police surveillance of Black and Latino neighborhoods, mass incarceration, and racial bias in convictions [28–30]. These inequities may also shape IPV/SV survivors’ intentions to engage with police. Limited past research documents fears of race-based insensitivity, discrimination, perceived social responsibility to protect perpetrators of the same race, and perception of a biased justice system [18, 31–33]. Crenshaw’s intersectionality framework was developed in part to examine race and gender power disparities as they relate specifically to violence against women [19], making this framework uniquely relevant for clarifying the structural and community-level determinants of IPV/SV-related police contact.

We conducted qualitative research with IPV/SV survivors to understand structural and community determinants of police contact in Baltimore, MD. Baltimore represents one of many racially diverse mid-sized US cities with entrenched racial/ethnic disparities. In 2010, Maryland’s incarceration rate per 100,000 was 1437 for Blacks, 311 for Hispanics, and 310 for Whites [34]; these patterns predominantly reflect Baltimore (incarceration rate 1255 per 100,000 relative to 383 in Maryland overall) [35]. A 2016 Department of Justice investigation of the Baltimore Police Department revealed racial discrimination, use of excessive force, and unconstitutional use of force and retaliation against citizens, as well as gender biases, minimization, undue skepticism, and victim-blaming specific to IPV/SV [36]. Disproportionate and systematic dismissal of sexual violence cases in Baltimore has been documented since 2009 [37]. We use an intersectional lens [19] that examines the interplay of disparate power dynamics specifically related to gender and race, against a backdrop of concentrated economic disadvantage, to explore where and how these power imbalances and inequities affect police contact following IPV/SV.

Methods

Sample

Community-based recruitment facilitated by IPV/SV support programs and social media was conducted from November 2017 to April 2018. Eligible participants (1) were at least 18 years old, (2) self-identified as female (including transgender women), (3) experienced IPV and/or SV within the past 12 months, and (4) were fluent in English. The final sample size (n = 26) was determined by saturation. Our project leadership and implementation team was diverse with regard to race/ethnicity (two South Asian women, two Black women, three White women).

Procedures

In-depth interviews were conducted by trained, racial/ethnically diverse research staff of two South Asian women and one Black woman, in private locations, following informed consent and a brief demographic survey. Interviews lasted 60–90 min and followed a semi-structured guide including police-community relationships, and considerations for violence-related help-seeking from police and other sources. Aligned with ethical best practices for violence-related research, participants received a distress screen, a local resource sheet, and $25. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Data Analysis

Qualitative analysis followed the constant comparison method, which is derived from grounded theory [38–40] and has been recommended for research specific to social justice and inequity [41]. The research team read an initial set of transcripts (n = 2) and generated themes in an initial codebook, which was refined and applied independently by two coders to two additional transcripts followed by review for consistency in application. After refining the codebook and finalizing a shared understanding of codes, the remaining interviews were coded independently. Ongoing team debriefing during data collection, and audit trail during analysis, enhanced reliability. The research team met regularly to maintain inter-coder agreement in the coding structure application. Preliminary results were shared with the advisory team for input and collaborative interpretation. The current analysis reports on themes specific to police-related decision-making for IPV/SV.

Results

Consistent with the underlying population in Baltimore City, our sample was 73% Black, 19% White, and 8% other, including multiracial (Table 1). The majority reported an annual income less than $10,000. Given the racial/ethnic distribution study population, and the underlying population in this setting, the racial/ethnic disparities and inequities reflected in our study are most specific to the Black experience.

Table 1.

Sample demographic characteristics

|

n = 26 % (n) |

|

|---|---|

| Age range (mean) | 24–58 (34) |

| Race | |

| Black | 73.1 (19) |

| White | 19.2 (5) |

| Other including multiracial | 7.7 (2) |

| Relationship status | |

| Single | 61.5 (16) |

| Married | 15.4 (4) |

| Divorced/separated | 15.4 (4) |

| Other | 7.7 (2) |

| Highest grade or year of school completed | |

| Grades 9 through 11 (some high school) | 23.1 (6) |

| Grade 12 or GED (high school graduate) | 26.9 (7) |

| College 1 year to 3 years (some college or technical school) | 34.6 (9) |

| College 4 years or more (college graduate) | 15.4 (4) |

| Household annual income (n = 24) | |

| Less than $10,000 | 58.3 (14) |

| $10,000 or more | 41.7 (10) |

| Experienced IPV in the past 12 months | |

| Yes | 100 (26) |

| No | 0 |

| Experienced SV in the past 12 months | |

| Yes | 53.8 (14) |

| No | 46.2 (12) |

| Were the police called (n = 25) | |

| Yes | 64.0 (16) |

| No | 36.0 (9) |

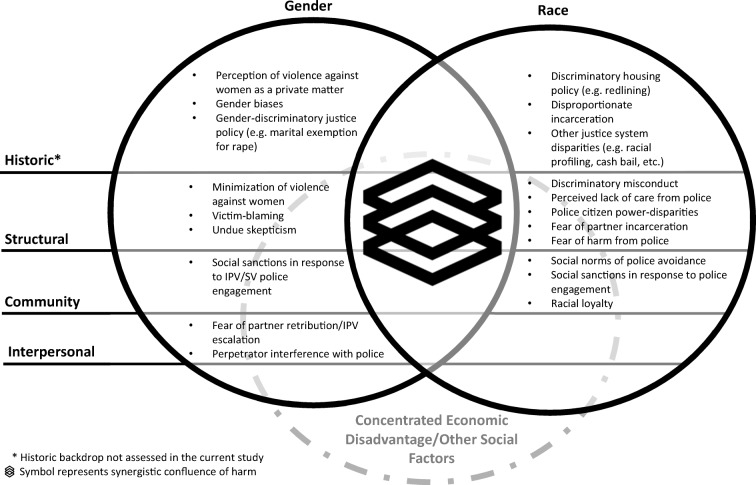

Qualitative results are organized by socio-ecologic level, specifically structural, community, and interpersonal. We present a visual representation of the intersectionality framework (Fig. 1) as applied to our study, i.e., with a focus on inequity and disparate power dynamics specifically related to gender (female) and race (primarily Black as compared with White), while acknowledging the context of concentrated economic disadvantage that serves as a backdrop in our study setting. The overlapping area of the Venn diagram contains a symbol that represents a confluence of harm that can be understood as synergistic rather than additive, consistent with the intersectionality framework [19].

Fig. 1.

Intersectionality of gender and race-related barriers to police contact for IPV/SV across the socio-ecologic model

Structural

Structural influences centered on inequitable treatment based on race/ethnicity, gender, and other domains of social marginalization.

Police Misconduct and Historic Discrimination Based on Race/Ethnicity and Other Factors

Discriminatory Police Misconduct

Police-community relationships were described as tense with discriminatory misconduct.

[people in the neighborhood] can be harassed by cops… We’ve got some that are on medication for having mental disabilities. They be harassed, being called junkies when they actually not. The guys they be harassing, some of them actually do have jobs. Just out there chit chatting, not breaking any laws. —Interview 25, Black, age 37

They’re doing an investigation and questioning you but the whole time, they’ll [police] beat you, send you on your way, take your stuff. —Interview 4, Black, age 30

Women were hesitant to discuss police treatment in the context of race. Where addressed, racial disparities and a perceived race-based double standard undermined trust in police.

When it’s the White people, it’s always an excuse for how they handle them, how they deal with them. But when it’s a Black person, they want to make an example out of us as Black people, whether it’s a man, whether it’s a woman. —Interview 23, Black, age 36

Race-based disrespect, discrimination, and mistreatment amplified these feelings.

The Caucasian police will call them “boy,” just racist remarks, stuff like that. It’s kind of disrespectful. —Interview 24, Black, age 27

You can get some cops who can come to and they can see African American. They can see the age range and they can just assume that they’re part of this group and they can treat them differently. —Interview 8, Black, age 35

Perceived Lack of Care or Concern from Police

Many women attributed the disregard they experienced and observed in police interactions to a lack of concern for their well-being and that of their communities, as explained by one participant following a non-IPV/SV incident:

The first incident, being attacked in my backyard, literally, I hated the police that day. The attitude was just so disassociated, so disrespectful. I think it made it worse for me because one of the officers was a woman. I’m sitting there hysterical with cuts on my arm. To look up and see her texting.…it was real disheartening that when a situation like that, you have some officers who don’t care. —Interview 12, Black, age 46

Women linked this apathy to explicit contempt and devaluation of their lives, as manifested most profoundly in disproportionate incarceration and its cascade of economic consequences.

I’m saying everything is jail. That’s the worst thing you can do, other than kill a black man or a person period, is to throw them in jail…Then when you get out looking for jobs, it’s crippling. It’s just a way to really dehumanize somebody, I guess. Like, really yeah, they’re less than. That’s what they look at us now as anyway.

She went on to explain that the police’s response to violent crime violated her right to be heard.

Anytime you don’t want to hear about what I have to say, you don’t care… You know you would want to be heard and you would want to have a voice in the situation like that. You are just denying my right for that. You don’t think of me as a human being. —Interview 11, Black, age 26

Power Disparities

Women described power differentials relative to police, wherein police authority made encountering a “bad cop” uniquely threatening. The dynamic they described echoed that with an abusive partner, prompting women to adopt a survival-based deference that limited capacity to advocate for justice.

It’s just abuse. It’s not people who in power. As a matter of fact, people who don’t have power, adults over children. When I think power, I think oppressors. I call them all oppressors. I think they’re oppressors. They’ve got some type of power. Maybe mental power, physical power, anything, but the authority’s got the most power. —Interview 4, Black, age 30

Women’s sensitivity to these disparate power dynamics was reflected in their description of a tacit understanding of how to manage police encounters, thus minimizing their own needs.

The only way to deal with a bad cop is by letting him know that he has the power. That’s the only way that you’re walking out of that situation. —Interview 8, Black, age 35

This navigation of competing priorities is emblematic of how Black Americans have been taught to manage police dynamics in light of historical discrimination and ongoing instances of police violence. The utility of the intersectional framework is evident; for Black women survivors of IPV, the consequent layering of IPV-related trauma and power disparities with their perpetrators, coupled with race-related concerns about police power disparities, created unique barriers to engagement with police following violence experiences. This barrier was not discussed by any White study participants.

Fear of Harm from Police

Black women also explained their fear that contacting police could result in significant harm to their partners.

I’m like, if I would call the police, maybe it’ll escalate, and he can get hurt or they can kill him…I never really called the cops on my husband regarding the situation because I was too scared...I’m like, what if it turns out wrong? I’m here seeking help, and then he ends up getting killed in the process. I was too scared. —Interview 10, Black, age 33

This reflected an awareness of the reality of police brutality in their communities, itself a legacy of historical tensions between police and the Black urban community in Baltimore City and elsewhere. This concern underscores the intersectional nature of the barriers Black women face when considering turning to police following IPV/SV, which differed from those of their White counterparts in this study.

Fear of Partner Incarceration

Fear of partner incarceration was a deterrent to police contact. Incarceration was considered an overzealous response that often did not respect women’s wishes.

That’s why I didn’t call. Because I knew he was going to go to jail… That’s why I didn’t say anything. I was scared he was going to go to jail. —Interview 25, Black, age 37

Sometimes you have officers who love their badge. They might not make the right decisions with their badge, but the badge is what they live for. If you get one of those police officers with a person with domestic violence, there is no telling what they might do to that person. They feel justified because it was like a officer vigilante. —Interview 8, Black, age 35

Racial incarceration bias further perpetuated women’s reluctance to engage police.

It was like [police] just wanted to take another black man and just put him in jail. —Interview 24, Black, age 27

Underpinning both fears was the potential for irreversible consequences to the partner and to the family economic stability, which could further compound the overall damage incurred. These consequences were intimately understood by Black women in this sample living with the current legacy of mass incarceration. By contrast, no such incarceration-related fears were raised by White women in our study.

Gender Discrimination: Minimization, Justification, and Devaluing of Violence against Women

Police minimization of IPV/SV undermined women’s confidence in the justice system. Women described calling the police multiple times only to be met with indifference and treated as though their circumstances were inevitable.

They come with this attitude, like, yeah, it’s going to happen again. “You need to leave him alone. It’s no need to do this if you’re going to turn around and be with him again”. —Interview 22, Black, age 31

At times, this minimization was accompanied with victim-blaming and a gender double standard, a relic of historic gender biases.

I, in the past, was intimate with this guy. Because I already was intimate with him, I took it as the police saying, “Well, you already had sex with him before. Why not have sex with him again?” That’s how I took it. That’s how the police looked at it. —Interview 1, Black, age 38

They feel as though that the woman automatically did something to provoke the man. —Interview 13, Black, age 25

Women believed that invoking the IPV/SV justice response would be futile, which amplified their feelings that their IPV/SV experiences were not taken seriously.

Some people scared to reach out to the police, when you don’t really get the help that you need anyway…What if you reach out to the police and then you get beat up the next day, or later on at night? Because what do they actually do? —Interview 9, Black, age 25

I’m saying, there is no point in calling the police because, of course they would arrest him but he would just get right back out. That’s been happening every single time, he gets right back out the next day or within two days. Then, it’s hell for me because he was just in jail because I sent him there. —Interview 38, White, age 24

Police failure to understand the complexities of IPV and women’s resulting lack of confidence in the justice system discouraged women from reporting the violence they had experienced.

The intersection of race and gender inequity at the structural level is exemplified by the paradox facing Black women following IPV/SV, in which an overzealous and racially motivated police response could harm their partners and families, yet an underwhelming, minimizing response might not sufficiently protect their safety. Recognition of both of these undesirable scenarios discouraged women’s engagement with police following IPV/SV.

Community

Women explained deeply rooted social norms against contacting law enforcement for any reason in an outgrowth of historical race-based discrimination and stigma towards poor urban communities.

I don’t know. I was never taught to call police when somebody laid their hands on you. I’ll do it from now on but...Yeah, that’s how I was raised. —Interview 20, White, age 28

Nobody just calls the police, especially in Baltimore City. That’s the last thing we want to be showing up. —Interview 11, Black, age 26

I really don’t know what would have made me call…This man tried to kill me almost three times, and I still didn’t call, so I don’t know what else is left. —Interview 25, Black, age 37

You know the police come they going get locked up... They don’t want them around. —Interview 18, Black, age 27

Individuals who defied social norms of police avoidance faced severe sanctions.

A woman kept calling the police. People was outside, she called the police. They were stealing his bike, she called the police. They was doing things to her house, she called the police. Last time she called the police, the police left. As soon as the police left, somebody killed her in front of her kids. Her body fell in her kids’ arms. —Interview 8, Black, age 35

The possibility of such sanctions was a potent deterrent to police engagement for any type of crime, including IPV/SV.

Social Sanctions in Response to IPV/SV Police Engagement

The same sanctions applied for IPV/SV police contact, as explained by one participant following police contact for severe partner-related danger.

Not speaking to me or walking the other way. People didn’t come to my daughter’s birthday party this weekend. Her grandmother didn’t come. Her grandmother didn’t call her. Cousins...

She articulated that her community had actively deprioritized her own safety in favor of resistance to overincarceration; a clear example of how the intersection of gender and race affects the context in which decisions about safety are made. The spectre of mass incarceration and its attendant consequences is juxtaposed with the desire for safety.

…you’re basically mad at me because I didn’t let your son kill me or that I didn’t let your cousin kill me…I wanted to get free and I needed to make a way to get out of there. Now those very people are turning their [indecipherable] up at me, because he’s incarcerated, and I got him incarcerated. —Interview 8, Black, age 35

Another participant described child custody-related sanctions from her partner’s family following her partner’s incarceration.

It’s not like they want [the kids]. It’s because just to be spiteful…Because I took him away from them, they want to take what’s mine. The kids are really attached to me, and they know that. —Interview 24, Black, age 27

These social sanctions put women in the position of risking compounded harm through the community consequences of breaking with social norms. Results illustrate that racial loyalty or intragroup discipline can be sustained and operationalized through social sanctions implemented by community members.

Interpersonal

Fear of Escalation and Partner Retribution

Fear of partner retribution was an overwhelming theme in interpersonal barriers to police contact.

There’s a lot of reason why people don’t call, scared, fear of retaliation, scared for their life. They’ll come back and kill them. —Interview 1, Black, age 38

I think some people do want the help, but they’re terrified to call. I probably wouldn’t be alive if he’d ever seen that I had called 911 off from my phone, before the cops got there. That’s a reality. It’s a fear. —Interview 15, Multiracial, age 34

Perpetrator Interference with Police

Women also described their partners’ active attempts to manipulate police, which discouraged future police engagement particularly when police believed the perpetrator.

I realized he had taken my house keys and my cellphone. I had no way to contact anybody to do anything. He closed our joint bank account. At seven o’clock at night, the police showed up with a protective order saying that I had to leave, and I couldn’t take my son with me. —Interview 20, White, age 28

He called the cops after I called the cops. He saw me on the phone with the cops through the window. So he hurried up and called the cops and told them that I was a crazy ex-girlfriend that just showed up at his house banging on the door. Mind you, I’ve lived there for years. When the cops came there, they told me, “Well, you don’t live here.” —Interview 38, White, age 24

One woman explained that her partner had her arrested specifically to deter her from calling the police on him in the future.

…when both of us finally came home [from jail], he was like, “You keep getting me locked up and you’re not going to keep getting me locked up. You’ve got a taste of your own medicine”. —Interview 4, Black, age 30

Discussion

This study describes structural and community determinants of police contact following IPV/SV, with an emphasis on race and gender inequities and their intersection. Without addressing these dual and interwoven inequities, the current justice response to IPV/SV will continue to suffer from underreporting, particularly for the women of color who are disproportionately affected by IPV/SV [5]. Findings are timely in advancing a national dialogue that devotes unprecedented attention to racial inequities within the justice system, including police violence [42]. Findings are contextualized by sustained local recognition and demand for response to these issues in Baltimore City, as exemplified by the 2015 protests following the death of Freddie Gray while under police custody, as well as the 2016 Department of Justice investigation of the Baltimore Police Department [36]. The #MeToo movement that has gained global attention since 2017 has brought swift new attention to the barriers to victim support and justice following IPV/SV as well as sexual harassment and other misconduct [43]. Against this backdrop, our results articulate how the combination of both race and gender-based discrimination can undermine institutional trust in police and compromise health and safety. An intersectional lens is essential in understanding and resolving the multiple layers of inequity within IPV/SV response systems. Results argue for the simultaneous use of gender justice and racial justice frameworks in advancing health, justice, and safety for IPV/SV survivors with the ultimate goal of healthy communities.

Articulation of structural and community-based determinants of police reporting following IPV/SV advances a landscape that has focused primarily on interpersonal-, individual-, and incident-level factors. Our results demonstrate that individual-level determinants are shaped by structural inequities along lines of both race and gender, highlighting the need for an intersectional framework to address how unequal power dynamics across multiple identities interact to create distinct barriers to police engagement. Community norms of police avoidance rooted in historic experience of race-based discrimination were potent deterrents for contacting police for the Black women in our sample. The impact of these community norms is likely amplified for IPV/SV survivors, who often turn first to their informal networks before seeking support through formal systems [44]. It is critical to address community norms that discourage access to services including police. Research and practice to enhance the IPV/SV response must address systems-level inequities as well as the community social context of social sanctions against police engagement.

The intersection of racial and gender oppression is encapsulated in our results. Black women fear overzealous law enforcement response rooted in racial discrimination, contextualized by historic and present-day police brutality, abuse, and discriminatory policing in their communities. This is often expressed in persistent racism, more broadly. Simultaneously, women express dire frustration and discouragement with an underwhelming IPV/SV justice response characterized by nonchalance, minimization, and victim-blaming. Futility in the police response has long been described among IPV/SV survivors, and IPV/SV-related laws have suffered underenforcement. For low-income Black women, the context of economic instability further amplifies the issues of IPV/SV devaluation coupled with the threat of a racially motivated and disproportionately harsh police response. Pursuing gendered justice through IPV/SV police contact comes with the dual risks of potential racial injustice, and the threat of further economic instability incurred through dissolving the partnership or partner incarceration.

Our results, guided by the intersectionality framework, clarify that addressing police reporting barriers that solely relate to the minimization of IPV/SV will be insufficient for women whose concerns are also deeply rooted in racial discrimination, economic instability, and other forms of structural inequality. Results echo long-held concerns among scholars that fear of police among women of color could reflect concern for police doing too much rather than not enough, as well as the inherent conflict in wanting abuse to end against fear of enabling unjust treatment of their male partners by an oppressive system. At the community level, women currently weigh their needs for safety, justice, and intervention following IPV/SV against the blame they risk for seeking and exacting consequences, presenting a clear opportunity for social norms change as well as advocacy to support survivors. Current findings add urgency to calls to better align justice responses with the needs of victims.

The growing evidence linking police brutality and systemic disempowerment via incarceration and racism with health disparities has given rise to new public health frameworks that articulate the impact of structural injustice [42]. Yet currently, research and dialogue on police brutality focus predominantly on men’s experiences. Current findings articulate the impact of justice-related racial/ethnic disparities on IPV/SV as a dominant public health and criminal justice issue for women. Thus, results demonstrate the need for an intersectional approach that blends gender justice and race justice frameworks to fully understand and address police dynamics and their impact on women’s health, safety, and access to justice.

We acknowledge the many challenges inherent in depicting intersectionality, particularly how to visualize and understand the synergy of overlapping oppressions. While this concept is best visualized using multiple dimensions, our figure provides an organizational framework for current results and focuses on race and gender as key domains in our study. Other applications of intersectionality could uncover similar factors (e.g., discriminatory misconduct) within additional domains of marginalization (e.g., concentrated economic disadvantage). Direct police harassment and abuse likely further undermine police engagement, particularly for women with multiple marginalized identities such as gender non-conforming, women of color, drug-involved and criminal-involved. Our visualization approach should not reinforce a reductive framework that considers individuals as a sum of their identities. Future research is needed to conceptualize areas of overlapping oppression and understand the nature of effects, e.g., additive, multiplicative, or otherwise synergistic.

Several additional limitations should be noted. This study was conducted in a single city of intense racial inequity and concentrated economic disadvantage. In settings where disparities are less striking, results may differ. Recruitment relied heavily on collaborating IPV/SV support organizations whose client experiences may be disproportionately severe or unique. This qualitative study does not allow for quantification of the relative influences of structural factors as compared with individual or interpersonal considerations, nor relative impact of specific factors. Police intervention outcomes are shaped by many factors including arrest and prosecution, and threats and revictimization during legal proceedings [21, 22]; police intervention may not be sufficient to prevent subsequent victimization or homicide. Finally, while recommendations and conclusions are common across victims of IPV and IPV/SV, we note that women were more forthcoming in their discussion of police-related decisions following IPV as compared with SV, in part likely due to the more chronic nature of IPV experiences, and in turn the multiple points at which they may have considered police involvement.

Our national public health and safety systems require change to ensure equitable access for IPV/SV survivors. The 2016 US Department of Justice guidance on preventing gender bias in IPV/SV police response [45] and the 2015 Implementation Guide from the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing [46] provide critical direction for addressing race and gender-based inequity and should be fully implemented. The deep roots of police mistrust related to IPV/SV minimization coupled with fear of discriminatory treatment demonstrate the urgent need to expand justice solutions for responding to IPV/SV, particularly for Black women. Restorative justice approaches that fundamentally seek to repair harm through community engagement, restoration, and accountability [47–49] represent one valuable solution for expanding the current carceral response to IPV/SV. Transformative justice models go further still by positioning the restorative principles outside the justice system, to hold communities accountable for their role in violence and transform the conditions that created abuse [50]. Further research is needed to optimize, operationalize, and fully evaluate these approaches, with an emphasis on outcomes of safety and equity. Finally, because informal networks and local support services often serve as the first line of response for IPV/SV survivors [8], strengthening this support network with the tools and capacity to respond to IPV/SV survivors’ needs is critical. The nation’s unprecedented attention to justice reform must strive for race- and gender-based equity within the IPV/SV response.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Bloomberg American Health Initiative, which is funded by a grant from the Bloomberg Philanthropies (Spark Award, Decker), with additional support from the Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau (T76MC00003), and National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (1L60MD012089-01, Holliday; 5U54MD000214-17). We wish to thank our participants for trusting us with their experiences, and we thank our reviewers for exceptionally thoughtful input.

Authors’ Contributions

MRD and CNH designed the study and wrote the first draft; RS and ZH contributed to writing. ZH, RS, CNH led data collection and analysis with oversight from MRD.

JM, JD, and LG provided contextual oversight, ongoing interpretation of results, and substantive revisions to the article.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Smith SG, Zhang X, Basile KC, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2015 Data Brief. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.; 2018.

- 2.Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359(9314):1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrosky E, Blair JM, Betz CJ, Fowler KA, Jack SPD, Lyons BH. Racial and ethnic differences in homicides of adult women and the role of intimate partner violence - United States, 2003-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(28):741–746. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6628a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Leading Causes of Death in Females, 2015. 2018. Accessed 08/01/2018.

- 5.Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011.

- 6.Jack SPD, Petrosky E, Lyons BH, et al. Surveillance for Violent Deaths - National Violent Death Reporting System, 27 States, 2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Surveill Summ. 2018;67(11):1–32. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6711a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.USAID., US Department of State. United States Strategy to Prevent and Respond to Gender-Based Violence Globally. USAID and Department of State, Government of the United States of America; 2012.

- 8.Decker MR, Wilcox HC, Holliday CN, Webster DW. An integrated public health approach to interpersonal violence and suicide prevention and response. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(1_suppl):65S–79S. doi: 10.1177/0033354918800019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Truman JL, Morgan RE. Criminal Victimization, 2015. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2016.

- 10.Langton L, Berzofsky M, Krebs C, Smiley-McDonald H. National Crime Victimization Survey: Victimizations Not Reported To Police, 2006-2010. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, US Department of Justice; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie M, Lynch JP. The effects of arrest, reporting to the police and victim services on intimate partner violence. J Res Crime Delinq. 2017;54(3):338–378. doi: 10.1177/0022427816678035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akers C, Kaukinen C. The police reporting behavior of intimate partner violence victims. J Fam Violence. 2009;24(3):159–171. doi: 10.1007/s10896-008-9213-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y, Ullman SE. Women’s reporting of sexual and physical assaults to police in the National Violence Against Women Survey. Violence Against Women. 2010;16(3):262–279. doi: 10.1177/1077801209360861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGregor MJ, Wiebe E, Marion SA, Livingstone C. Why don’t more women report sexual assault to the police? Can Med Assoc J. 2000;162(5):659–660. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zweig JM, Newmark L, Raja D, Denver M. Sexual Assault Medical Forensic Exams and VAWA 2005. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marchetti CA. Regret and police reporting among individuals who have experienced sexual assault. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2012;18(1):32–39. doi: 10.1177/1078390311431889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fagan J. The Criminalization of DomesticViolence: Promises and Limits. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolf ME, Uyen L, Hobart MA, Kernic MA. Barriers to seeking police help for intimate partner violence. J Fam Violence. 2003;18(2):121–129. doi: 10.1023/A:1022893231951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crenshaw K. Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 1991;43(6):1241–1299. doi: 10.2307/1229039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. Univ Chic Leg Forum. 1989;140:139–167. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jordan CE. Intimate partner violence and the justice system - an examination of the interface. J Interpers Violence. 2004;19(12):1412–1434. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bachman R. The factors related to rape reporting behavior and arrest - new evidence from the national crime victimization survey. Crim Justice Behav. 1998;25(1):8–29. doi: 10.1177/0093854898025001002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fedina L, Backes BL, Jun HJ, Shah R, Nam B, Link BG, DeVylder JE. Police violence among women in four US cities. Prev Med. 2018;106:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bennice JA, Resick PA. Marital rape: history, research, and practice. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2003;4(3):228–246. doi: 10.1177/1524838003004003003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Desmond M, Papachristos AV, Kirk DS. Police violence and citizen crime reporting in the Black community. Am Sociol Rev. 2016;81(5):857–876. doi: 10.1177/0003122416663494. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts DE. The social and moral cost of mass incarceration in African American communities. Stanford Law Rev. 2004;56(5):1271–1305. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tyler TR. Policing in black and white: ethnic group differences in trust and confidence in the police. Police Q. 2005;8(3):322–342. doi: 10.1177/1098611104271105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gase LN, Glenn BA, Gomez LM, Kuo T, Inkelas M, Ponce NA. Understanding racial and ethnic disparities in arrest: the role of individual, home, school, and community characteristics. Race Soc Probl. 2016;8(4):296–312. doi: 10.1007/s12552-016-9183-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baumgartner FR, Epp DA, Shoub K. Suspect Citizens: What 20 Million Traffic Stops Tell Us About Policing and Race. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pettit B, Gutierrez C. Mass incarceration and racial inequality. Am J Econ Sociol. 2018;77(3–4):1153–1182. doi: 10.1111/ajes.12241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tillman S, Bryant-Davis T, Smith K, Marks A. Shattering silence: exploring barriers to disclosure for African American sexual assault survivors. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2010;11(2):59–70. doi: 10.1177/1524838010363717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rasche CE. Minority women and domestic violence: the unique dilemmas of battered women of color. J Contemp Crim Justice. 1988;4(3):150–171. doi: 10.1177/104398628800400304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Washington PA. Disclosure patterns of Black female sexual assault survivors. Violence Against Women. 2001;7(11):1254–1283. doi: 10.1177/10778010122183856. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakala L. Breaking Down Mass Incarceration in the 2010 Census: State-by-State Incarceration Rates by Race/Ethnicity. Justice Policy Institute; 2014.

- 35.The Right Investment? Corrections Spending in Baltimore City. Prison Policy Intiative at the Justice Policy Institute; 2015.

- 36.US Department of Justice . Investigation of the Baltimore City Police Department. Washington, DC.: U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fenton J. City Rape Statistics, Investigations Draw Concern. Baltimore Sun. June 27, 2010.

- 38.Taylor SJ, Bogdan R, DeVault ML. Introduction to qualitative research methods : a guidebook and resource. 4th ed. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2016.

- 39.Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research design : qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 5th ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE; 2018.

- 40.Glaser B, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine de Gruyter; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Charmaz K. Grounded Theory Methods in Social Justice Research. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y, eds. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2011:359-380

- 42.Alang S, McAlpine D, McCreedy E, Hardeman R. Police brutality and Black health: setting the agenda for public health scholars. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(5):662–665. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Neil A, Sojo V, Fileborn B, Scovelle AJ, Milner A. The #MeToo movement: an opportunity in public health? Lancet. 2018;391(10140):2587–2589. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30991-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sylaska KM, Edwards KM. Disclosure of intimate partner violence to informal social support network members: a review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2014;15(1):3–21. doi: 10.1177/1524838013496335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Department of Justice. Identifying and Preventing Gender Bias in Law Enforcement Response to Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence. Department of Justice; 2016.

- 46.COPS Office . President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing Implementation Guide: Moving from Recommendations to Action. Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goodmark L. Decriminalizing Domestic Violence. Oakland, CA: University of California Press; 2018.

- 48.Braithwaite J. Restorative justice & responsive regulation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002.

- 49.Goodmark L. Innovative criminal justice responses to intimate partner violence. In: Renzetti CM, Edleson JL, Bergen RK, editors. Sourcebook on Violence Against Women. 3. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coker DK. Transformative justice: anti-subordination processes in cases of domestic violence. In: Strang H, Braithwaite J, editors. Restorative Justice and Family Violence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]