Abstract

Background

The activation of stretch-activated channels (SACs) in cardiac myocytes, which changes the phases of action potential repolarization, is proven to be highly efficient for the conversion of atrial fibrillation. The expression of Na+ current in myofibroblasts (Mfbs) regenerates myocytes’ action potentials, suggesting that Mfbs play an active role in triggering cardiac rhythm disturbances. Moreover, the excitation of mechano-gated channels (MGCs) in Mfbs depolarizes their membrane potential and contributes to the increased risk of post-infarct arrhythmia. Although these electrophysiological mechanisms have been largely known, the roles of these currents in cardiac mechanics are still debated. In this study, we aimed to investigate the mechanical influence of these currents via mathematical modeling. A novel mathematical model was developed by integrating models of human atrial myocyte (including the stretch-activated current, Ca2+–force relation, and mechanical behavior of a single segment) and Mfb (including our formulation of Na+ current and mechano-gated channels’ current). The effects of the changes in basic cycle length, number of coupled Mfbs and intercellular coupling conductance on myocyte mechanical properties were compared.

Results

Our results indicated that these three currents significantly regulated myocyte mechanical parameters. In isosarcometric contraction, these currents increased segment force by 13.8–36.6% and dropped element length by 12.1–31.5%. In isotonic contraction, there are 2.7–5.9% growth and 0.9–24% reduction. Effects of these currents on the extremum of myocyte mechanical parameters become more significant with the increase of basic cycle length, number of coupled Mfbs and intercellular coupling conductance.

Conclusions

The results demonstrated that stretch-activated current in myocytes and Na+ current and mechano-gated channels’ current in Mfbs significantly influenced myocyte mechanical behavior and should be considered in future cardiac mechanical mathematical modeling.

Keywords: Mechano-gated channels (MGCs), Myocyte mechanics, Mathematical modeling, Myofibroblast–myocyte (Mfb–M) coupling, Stretch-activated channels (SACs), Voltage-gated sodium channels (VGSCs)

Background

As an alternative of experimental studies, computational modeling studies provide a powerful framework for gaining substantial insights of cardiac electrophysiology and mechanics in many aspects [1, 2]. For cardiac electrophysiological simulation, cardiac cell action potential (AP) models are built to represent current flow through ion pumps, channels, and exchangers [3, 4]. For mechanical simulation, the active stress/strain models and Hill’s three-element model have been formulated to lay out active contraction [5, 6].

Cardiac electrical activities have intimate connection with mechanical actions. The interaction between them is referred as electromechanical coupling (EMC) and mechanoelectrical feedback (MEF) [7]. As a major mechanism of the MEF, the stretch-activated channel (SAC) has been used to explain changes in electrophysiological behavior by mechanical deformation. Several cellular experimental and modeling studies have examined the impact of SACs on cardiac electrophysiology [8–11].

Recently, clinical data and simulation studies have provided some important insights into cardiac structural remodeling, especially fibrosis as a hallmark of permanent atrial fibrillation. Many of them verified that both fibroblasts and myofibroblasts (Mfbs) modulated cardiac electrical conduction, coordinated tissue remodeling, and integrated signals [12–14]. They have been considered as active communicators rather than non-excitable cells, which involve several currents like cardiac myocytes, e.g., the currents through potassium channels [15, 16], the non-selective transient receptor potential cationic channel subfamily M member 7 (TRPM7) [17], voltage-gated sodium channels (VGSCs) [18, 19], chloride channels [20], single mechano-gated channels (MGCs) [21], and voltage-dependent proton currents [22].

Computational models of atrial fibrosis have been used to investigate how fibroblasts modulate cardiac myocyte electrophysiology. At the cellular level, processes of fibrotic remodeling are represented as fibroblast proliferation and phenotype switching [23, 24]. Simulation results showed that coupling of fibroblasts or Mfbs to atrial myocytes resulted in shorter duration of the action potential (APD), slower conduction, and spiral wave breakups [25–28].

As a critical determinant of cardiac mechanics, fibroblast-mediated changes in extracellular matrix structure are also investigated by computational modeling. Cell compaction of collagen gels has been studied by explicitly calculating the mechanical equilibrium between each cell’s contractile forces and nearby collagen fibers’ mechanical properties [29, 30]. Infarct mechanics has been simulated by coupling agent-based model predictions to a finite element model [31, 32]. These studies have found that fibroblast alignment parallel to a strain cue provides a negative feedback to radical changes in local fiber orientations.

Previous studies mentioned above have examined cardiac myocyte functions in many aspects; however, no study to the our best knowledge has considered the following two aspects in Mfb–myocyte (Mfb–M) coupling, especially in EMC: (1) the stretch-activated ion channel current (ISAC) in myocytes, which influences cardiac myocytes electrophysiological characteristics under stretching [33, 34]; (2) the currents through VGSCs (INa_Mfb) and MGCs (IMGC_Mfb) in Mfbs, which could influence Mfb properties and contribute to EMC in cardiac pathologies [18, 21].

Our previous study has found that INa_myofb and IMGC_Mfb regenerated APs in myocytes and Mfbs [28]. In this study, we aimed to investigate the role of ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb in the mechanical contraction of cardiac myocyte. Simulation results of human atrial myocyte segment mechanical dynamics with different gap-junctional conductance (Ggap), number of coupled Mfbs and basic cycle lengths (BCLs) were examined.

Results

Effects of ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb on atrial myocyte AP, [Ca2+]i, and the normalized force

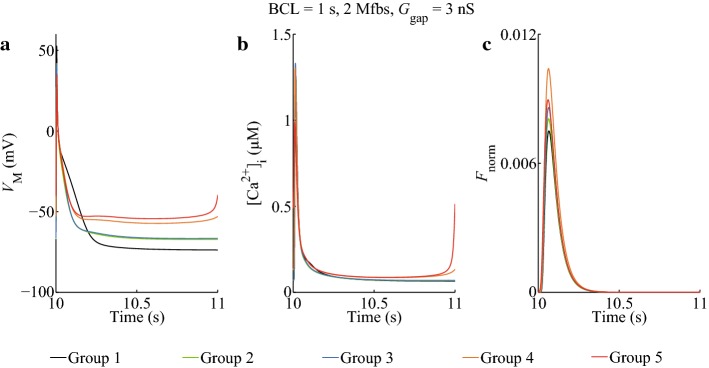

Figure 1 shows the combinational effects in five groups (see “Simulation protocol” section) of ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb on the membrane potential, intracellular Ca2+ concentration and the normalized force (Fnorm) of myocytes with a Ggap of 3 nS and a BCL of 1 s. For myocytes, coupling Mfbs (Group 2-5) resulted in gradual decrease of myocyte membrane potential amplitude (Vmax) and APD at 90% repolarization (APD90), and increase of the resting myocyte membrane potential (Vrest) depolarization (Fig. 1a). Meanwhile, a spontaneous excitement was emerged in Group 5, in which the peak [Ca2+]i dropped significantly (Fig. 1b), indicating that ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb could result in discordant alternans. From the traces of Fnorm (Fig. 1c), it can be observed that the peak Fnorm increased after myocyte coupled to Mfbs. It was increased by 7.6% (Group 2), 14.5% (Group 3), 38.7% (Group 4), and 19.2% (Group 5) as compared to the control (Group 1). It was remarkable that Group 4 got the biggest Fnorm increment, which meant Fnorm of myocytes could be significantly enhanced by the combination of ISAC and INa_Mfb. However, the increment relatively declined in Group 5 with the introduction of IMGC_Mfb. This might suggest that deformation in myocytes enhanced Fnorm, while in Mfbs the deformation relatively hindered it. The effects of ISAC and IMGC_Mfb on the force of atrial myocytes were opposite, with ISAC increasing and the other one decreasing.

Fig. 1.

Effects of ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb on atrial myocyte a AP, b [Ca2+]i, and c Fnorm in five groups. BCL = 1 s, 2 Mfbs, Ggap = 3 nS

Effects of ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb on atrial myocyte segment mechanical parameters

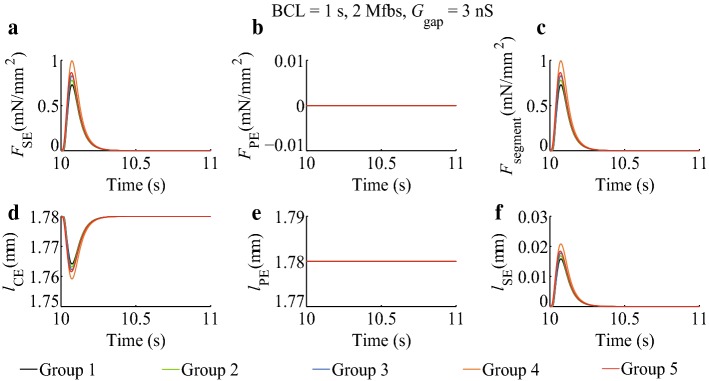

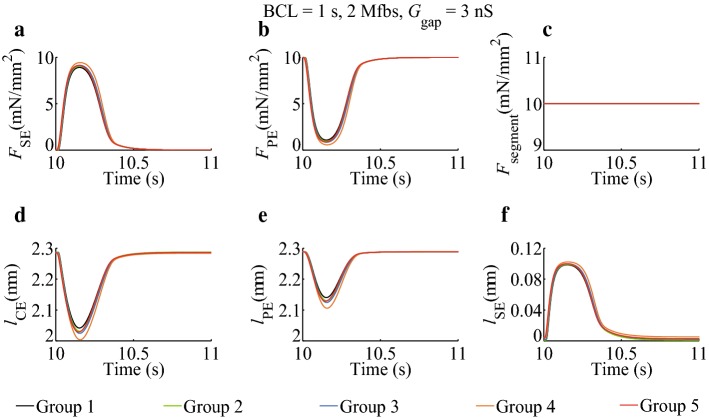

Traces of FSE, FPE, Fsegment, lCE, lPE, and lSE obtained in five groups for the simulations of isosarcometric contraction with sarcomere length of 1.78 µm are displayed in Fig. 2, and the ones for simulations of isotonic contraction with applied force of 10 mN per square millimeter (mN/mm2) are displayed in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

Effects of ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb on atrial myocyte segment mechanical parameters in isosarcometric contraction in five groups. BCL = 1 s, 2 Mfbs, Ggap = 3 nS

Fig. 3.

Effects of ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb on atrial myocyte segment mechanical parameters in isotonic contraction in five groups. BCL = 1 s, 2 Mfbs, Ggap = 3 nS

In isosarcometric contraction (Fig. 2), FPE and lPE in five groups were constant. Peak FSE increased when myocyte coupled to Mfbs. It was increased by 7.2% (Group 2), 13.8% (Group 3), 36.6% (Group 4), and 18.5% (Group 5) as compared to the control (Group 1). Using Eq. (14) (see “Mechanical behavior of a single segment” section), the increments in Fsegment were the same as those in FSE. On the contrary, lCE decreased when myocyte coupled to Mfbs. The minimum of lCE was dropped by 6.4% (Group 2), 12.1% (Group 3), 31.5% (Group 4), and 16.2% (Group 5) as compared to the control (Group 1). Using Eq. (15), the changes in lCE were equal to those in lSE. Similar to Fig. 1, Group 4 had the most significant change, indicating that the combination of ISAC and INa_Mfb played a significant role in determining myocyte segment mechanical behavior.

In isotonic contraction (Fig. 3), Fsegment in five groups was constant. Like Fig. 2a, the peak value of FSE also increased when Mfbs were coupled. It was increased by 1.6% (Group 2), 2.7% (Group 3), 5.9% (Group 4), and 2.5% (Group 5) as compared to the control (Group 1). The increments were smaller than those in isosarcometric contraction. According to Eq. (14), the decrements in FPE were equal to the increments in FSE. The minimum of lCE was dropped by 4.3% (Group 2), 7.4% (Group 3), 15.8% (Group 4), and 6.3% (Group 5) as compared to the control (Group 1), while the peak value of lSE was increased by 0.6%, 1.4%, 3.7%, and 0.9%, and finally, lPE were declined by 6.8%, 11.4%, 24.0%, and 10.0%. ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb not only changed the extreme values of lCE, lPE, and lSE, but also altered lCE and lSE in the resting stage. For example, the value of lSE in resting period was 0.0021 μm (Group 1), 0.0013 μm (Group 2), 0.0021 μm (Group 3), 0.0051 μm (Group 4), and 0.0032 μm (Group 5), respectively. Similarly, Group 4 has the most impact on the mechanical parameters.

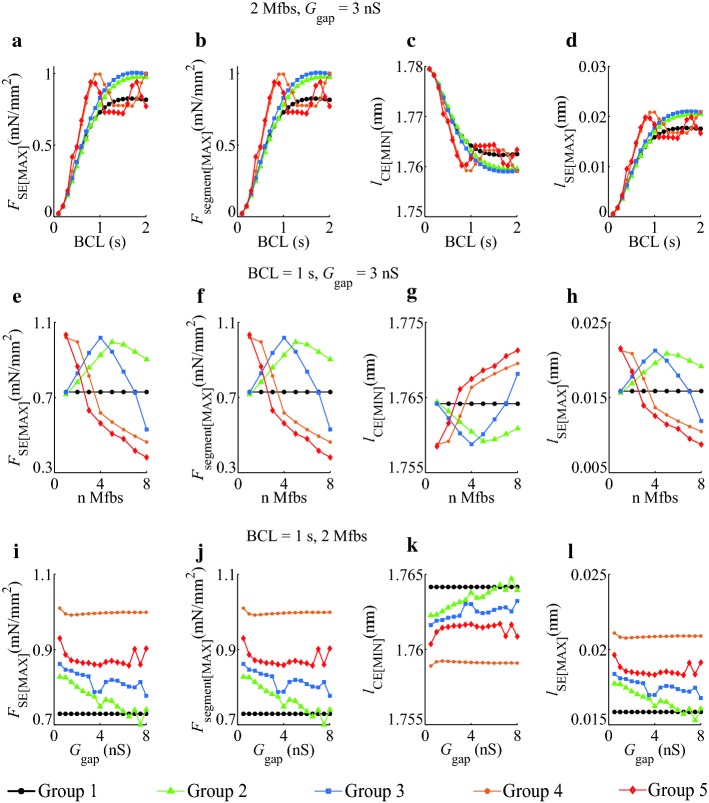

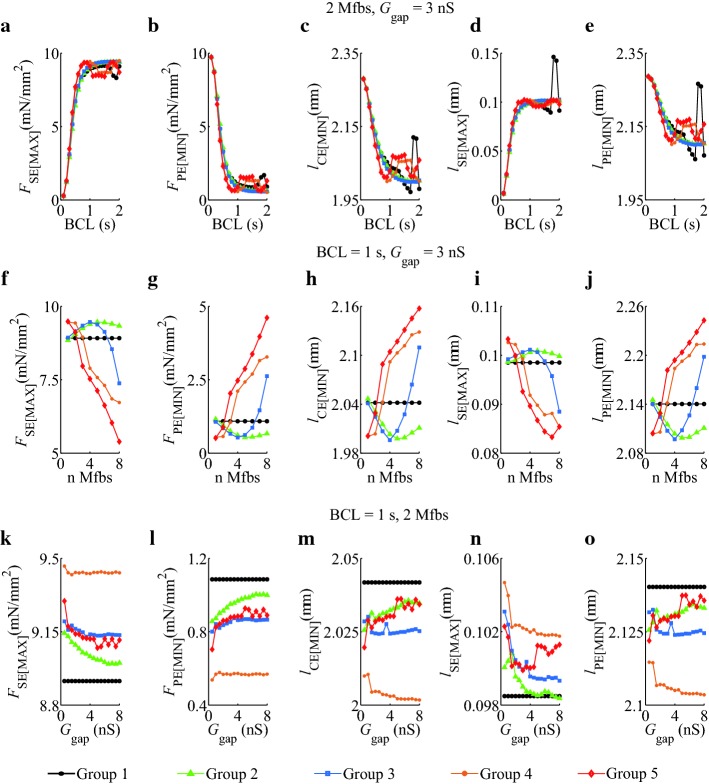

To investigate the effects of ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb on the extreme values of atrial myocyte segment mechanical parameters, we simulated five groups with different BCLs, Mfb–M ratios, and Ggap in both isosarcometric contraction (Fig. 4) and isotonic contraction (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Effects of ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb on the extremum of FSE, Fsegment, lCE, and lSE as functions of BCL, Mfb–M ratio, and Ggap in isosarcometric contraction in five groups, a–d BCL = 0.1–2 s, Mfb:M = 2, Ggap = 3 nS, e–h BCL = 1 s, Mfb:M = 1–8, Ggap = 3 nS, and i–l BCL = 1 s, Mfb:M = 2, Ggap = 0.5–8 nS

Fig. 5.

Effects of ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb on the extremum of FSE, FPE, lCE, lSE, and lPE as functions of BCL, Mfb–M ratio, and Ggap in isosarcometric contraction in five groups. a–e BCL = 0.1–2 s, Mfb:M = 2, Ggap = 3 nS, f–j BCL = 1 s, Mfb:M = 1–8, Ggap = 3 nS, and k–o BCL = 1 s, Mfb:M = 2, Ggap = 0.5–8 nS

From the traces of the extremum of FSE, Fsegment, lCE, and lSE for BCL = 0.1–2 s (Fig. 4a–d), it could be observed that peak FSE (FSE[MAX]), peak Fsegment (Fsegment[MAX]), and peak lSE (lSE[MAX]) increased, and valley value of lCE(lCE[MIN]) decreased with increasing BCL, in isosarcometric contraction. When BCL was less than 1 s, FSE[MAX], Fsegment[MAX] and lSE[MAX] at each BCL increased and lCE[MIN] decreased in Groups 2–5 as compared to Group 1. Meanwhile, at each BCL, FSE[MAX], Fsegment[MAX], and lSE[MAX] in Group 4 reached their maximums, and lSE[MAX] obtained its minimum. This suggests that ISAC together with INa_Mfb had the key influence on myocyte mechanical parameters. The influence disappeared in Group 5, suggesting that the role of IMGC_Mfb in myocytes was opposite compared to ISAC. As BCL longer than 1 s, each parameter in Group 1 to 3 has increased or decreased as a same trend, whereas fluctuated in Group 4 and 5. These phenomena might be attributed to that ISAC and INa_Mfb enhanced atrial myocytes excitability and triggered spontaneous excitements at large BCLs. [Ca2+]i, the vehicle of EMC, also fluctuated, driving the undulation of mechanical behavior.

Figure 4e–h shows the extremum of four parameters with Mfb–M ratios ranging from 1 to 8. Parameters in Group 1 were constants as no Mfb was coupled to myocytes. Unlike the similar trends of five groups in Fig. 4a–d, the trends of Group 2 and Group 3 in Fig. 4e–h were close and mostly distributed over one side of Group 1, and the trends of Group 4 and Group 5 were similar and distributed over the other side. Our results demonstrated that introducing currents through SACs in myocytes and currents through MGCs in Mfbs in cardiac modeling could lead to different simulation results. In fact, the stretch ability and contractility of myocytes in fibrotic heart were quite different from those in normal heart. Integrated ISAC and IMGC_Mfb in cardiac simulation could help obtain more accurate and closer to experimental results.

Figure 4i–l shows the extremum of four parameters with Ggap ranging from 0.5 to 8 nS. Parameters in Group 1 were also constants. The variance of five groups was less than those in other settings (Fig. 4a–h), suggesting the relative small effects of Ggap on myocyte mechanical parameters. The traces of Group 2 to 5 were mostly distributed over one side of Group 1. Parameters at each Ggap in Group 4 got the highest or lowest value among five groups, and parameters in Group 5 took the second place, indicating that ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb played a strong role in atrial myocyte mechanical behavior.

The extremum of FSE, FPE, lCE, lSE, and lPE as functions of BCL, Mfb–M ratio, and Ggap in isotonic contraction are showed in Fig. 5.

In Fig. 5a–e, the parameters among five groups were close to each other. As BCL increased, the values in Group 1, 4 and 5 first increased and then decreased. In these groups, pure myocyte or integrating ISAC and IMGC_Mfb in fibrotic myocyte were more likely to cause discordant alternans and mechanical parameters fluctuation at big BCLs.

In Fig. 5f–j, the parameters in Group 2 always stayed over one side of Group 1 as the coupled ratio increased, while the parameters in other groups finally converged over the other side. It suggested that integrating ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb in fibrotic myocyte significantly influenced the myocyte segment mechanical behavior at large coupled ratios.

In Fig. 5k–o, the parameters in Group 1 were constant, and Group 2, 3, and 5 had the similar traces, while Group 4 got the highest or lowest values. Therefore, ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb had relative influences on mechanical parameters at large Ggap.

Discussion

This study investigated the roles of ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb in myocyte segment mechanical behavior. To address these issues, computational simulations of the coupled Mfb–M system were performed by employing a combination of models of the human atrial myocyte (including ISAC) and Mfb (including INa_Mfb and IMGC_Mfb), as well as models of Ca2+–force relation and myocyte mechanical segment. Specifically, effects of these currents with changes in (1) BCL, (2) the number of coupled Mfbs, and (3) Ggap on atrial myocyte segment mechanical parameters were investigated. The integration of ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb could result in (1) decreased Vmax and APD90, increased Vrest depolarization, and spontaneous excitements even discordant alternans at large BCLs, and (2) increased peak value of FSE, Fsegment, and lSE and decreased valley value of lCE in isosarcometric contraction, and increased peak value of FSE and lSE and decreased valley value of FPE, lCE, and lPE in isotonic contraction. Moreover, ISAC and IMGC_Mfb have relative effects on myocyte segment mechanical parameters.

Effects of ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb on atrial myocyte segment mechanical properties

Effects of ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb on the excitability of human atrial myocytes have been discussed in our previous study [28]. Here, we discussed the roles of these currents in myocyte segment mechanical behavior.

EMC and MEF were two known effects [7], but the physical role of MEF in EMC was still poorly understood. In general, ISAC, handling as the major mechanisms of the MEF, was reported to enhance the early phase of AP repolarization and prolong or delay the final phase of repolarization [9, 35, 36]. But the impact of ISAC on cardiac mechanics, to our best knowledge, has been rarely studied so far. In our present study, the stretch-activated currents had the most significant influence on myocyte segment mechanical parameters in both isosarcometric contraction and isotonic contraction.

For cardiac Mfbs, many studies have verified that mechanical cues activated cardiac Mfbs and led to increased production of extracellular matrix [37, 38]. Mfbs were regarded as a critical determinant of cardiac mechanics. Previous studies have used computational modeling to demonstrate the acute mechanical effects on cardiac fibroblast structure and organization [39, 40]. They found that an axial strain environment could guide fibroblast proliferation, orientation, and migration [31, 41, 42]. Several groups have simulated cell compaction of collagen gels by calculating mechanical equilibrium between each cell’s contractile forces and nearby collagen fibers’ mechanical properties. They reported that cellular organization is tightly linked to the mechanical feedback loop between cells and matrix [29, 30]. These studies were all about the stretch-induced responses of quiescent cardiac Mfbs. However, the inverse process, i.e., the Mfbs-induced responses of cardiac mechanics, has not been widely explored. Our results showed that coupling Mfbs changed myocytes mechanical properties. In addition, we compared the results of before and after adding INa_Mfb and IMGC_Mfb in the Mfb model, and found that the effects of IMGC_Mfb on the force of atrial myocytes were contrary to ISAC.

For INa_Mfb, many studies have been conducted to investigate how this current could influence Mfb proliferation [18, 43]. Our results showed that INa_Mfb decreased Vmax and APD90 and increased Vrest depolarization in myocytes. This depolarization changed diastolic Ca2+ levels and then altered myocytes mechanical behavior.

For IMGC_Mfb, experimental data have indicated that cardiac fibroblasts expressed functional MCGs, contributing to the cardiac MEF both under physiological and pathophysiological conditions [44, 45]. We assumed that it could affect myocytes mechanical characteristics like ISAC. Our results supported this hypothesis. In our simulations, IMGC_Mfb altered myocytes mechanical behavior. Interestingly, the effects of IMGC_Mfb and ISAC on myocyte segment mechanical parameters seemed to be opposite. Myocytes stretch activated ISAC and enhanced the influence on mechanical parameters, while Mfbs compression activated IMGC_Mfb and weakened the influence. Moreover, MGCs were activated by fibroblast compression and inactivated by fibroblast stretch [21], implying that IMGC_Mfb should be integrated in cell modeling only during cell compression, such as fibroblasts/Mfbs compression caused by stretching and dilatation of surrounding cardiac myocytes.

Mfb was a critical determinant of cardiac mechanics. Previous studies have demonstrated that abnormal quantity or organization of Mfb could lead to both systolic and diastolic dysfunction [12, 30, 46]. Besides, previous modeling work suggested that Mfb–M coupling contributed to arrhythmia formation [25, 47]. The key factors included BCL, the number of coupled Mfbs, and Ggap. Here, we integrated INa_Mfb, ISAC, and IMGC_Mfb into Mfb–M coupling and compared their effects on myocyte mechanical properties in different settings of BCL, Mfb–M ratio, and Ggap. To the best of our knowledge, this has not been examined before. With BCL, Mfb–M ratio, and Ggap increasing, impacts of these currents on the extremum of myocyte mechanical parameters became greater, as summarized in Figs. 4 and 5.

Limitations

Two limitations in the present study should be mentioned. First, functional roles of SACs in Mfbs were not considered. Direct proof of mechanoactivation of mechanosensitive channels in cardiac Mfbs was limited. A handful of experimental studies have found that mechanical cues could lead to the opening of so-called SACs, and transient receptor potential canonical channels were candidates for the stretch-activated currents measured in cardiac fibroblasts [48, 49]. However, the current–voltage relation of ISAC in Mfbs needs further study. Second, the breadth of this computational study needs to be extended. Our work focused on the scale of local cell–cell interactions. Other scales, such as scales of subcellular signaling, cell–matrix interactions, tissue remodeling, and organ level conduction properties, were not included in this preliminary study. In fact, processes across these scales did not occur in isolation but operated as an interconnected system with every level passing information to other levels. Therefore, multi-scale modeling frameworks still need to be developed, although they brought computational challenges, and such models involving cardiac Mfbs and fibrosis were still rare.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated the combinational effects of ISAC in myocytes and INa_Mfb and IMGC_Mfb in Mfbs on myocyte mechanical properties. Our results showed that the addition of ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb regulated the peak and valley values of myocyte mechanical parameters in both isosarcometric contraction and isotonic contraction. Effects of these currents on the extremum of myocyte mechanical parameters become more evident as BCL, Mfb–M ratio, and Ggap increased. The effects proved that the stretch-activated current in atrial myocyte and Na+ current and mechano-gated channels in Mfbs should be considered in future pathological cardiac mechanical mathematical modeling, such as atrial fibrillation and cardiac fibrosis.

Methods

Mathematical model was developed by integrating (1) the model of the human atrial myocyte [50], (2) the model of ISAC [33], (3) the model of Ca2+–force relation [51, 52], (4) the active model of the human cardiac Mfb [26], (5) our proposed formulation of INa_Mfb and IMGC_Mfb based on experimental findings from Chatelier et al. [18] and Kamkin et al. [21], and (6) the Hill three-element rheological scheme of a single segment of myocyte [53, 54]. In following sections, the details of each component of the model will be described.

The model of Mfb–M coupling

The Mfb–M coupling will be modeled based on [26], with the differential equations for the membrane potential of cardiac Mfb and myocyte are given by

| 1 |

| 2 |

where VMfb,i and VM represent the transmembrane potential of the ith coupled Mfb and the human atrial myocyte, Cm,Mfb and Cm,M represent the membrane capacitance of the Mfb and the myocyte, IMfb,i and IM represent the transmembrane current of the ith coupled Mfb and the human atrial myocyte, and Ggap represents the gap-junctional conductance. It is also noted that a negative Igap [i.e., Ggap(VMfb,i–VM)] indicates that the current is flowing from the myocyte into the ith Mfb, and n is the total number of coupled Mfbs.

Mathematical model of the human atrial myocyte

The mathematical model of the human atrial myocyte developed by Maleckar et al. [50], which is based on experimental data and has correctly replicated APD restitution of the adult human atrial myocyte, was adopted in this study. To examine the influence of the stretch on myocyte AP, the original model from Maleckar et al. is modified with the total ionic current of myocyte (IM) given as

| 3 |

where INa is fast inward Na+ current, ICaL L-type Ca2+ current, It transient outward K+ current, IKur sustained outward K+ current, IK1 inward-rectifying K+ current, IK,r rapid delayed rectifier K+ current, IK,s slow delayed rectifier K+ current, IB,Na background Na+ current, IB,Ca background Ca2+ current, INaK Na+–K+ pump current, ICaP sarcolemmal Ca2+ pump current, INaCa Na+–Ca2+ exchange current, ISAC stretch-activated current, and IStim stimulated current.

The model of ISAC

Kuijpers et al. [55] have conducted experimental studies and reported that ISAC in atrial myocytes is permeable to Na+, K+, and Ca2+ [33], and defined as

| 4 |

where ISAC,Na, ISAC,K, and ISAC,Ca represent the contributions of Na+, K+, and Ca2+ to ISAC, respectively. These currents are defined by the constant-field Goldman–Hodgkin–Katz current equation [56].

To introduce the effect of ISAC on intracellular Na+, K+, and Ca2+ concentrations ([Na+]i, [K+]i and [Ca2+]i), we replace equations of [Na+]i, [K+]i, and [Ca2+]i in Maleckar et al.’s model [50] as

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

where F is Faraday’s constant, Voli cytosolic volume, Idi Ca2+ diffusion current from the diffusion-restricted subsarcolemmal space to the cytosol, Iup sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ uptake current, Irel sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release current, and O buffer occupancy.

The model of the Ca2+–force relation

The model 4 of isometric force generation in cardiac myofilaments proposed by Rice et al. was adopted to model the Ca2+–force relation [51, 52]. The concentration of Ca2+ bound to high-affinity or low-affinity troponin sites is [HTRPNCa] and [LTRPNCa], respectively. The dynamics are governed as

| 8 |

| 9 |

where [HTRPN]tot represents the total troponin high-affinity site concentration, and and are the Ca2+ on- and off-rates for troponin high-affinity sites. [LTRPN]tot represents the total troponin low-affinity site concentration, and and are the Ca2+ on- and off-rates for troponin low-affinity sites.

The model of human atrial Mfb

The electrophysiological model of human atrial Mfb proposed by MacCannell et al. [26] was used in the present study. It includes time- and voltage-dependent K+ current (IKv_Mfb), inward-rectifying K+ current (IK1_Mfb), Na+–K+ pump current (INaK_Mfb), and Na+ background current (IB,Na_Mfb).

In addition, INa_Mfb and IMGC_Mfb are added in the Mfb model. According to our previous work [28], equations of INa_Mfb and IMGC_Mfb are formulated as

| 10 |

| 11 |

| 12 |

where is the maximum conductance of INa_Mfb (0.756 nS), ENa,Mfb the Nernst potential for Na+ ions, [Na+]c,Mfb the Mfb extracellular Na+ concentration (130.011 mM), [Na+]i,Mfb the Mfb intracellular Na+ concentration (the initial value is set as 8.5547 mM), and mMfb and jMfb the activation and inactivation parameters, respectively. To follow the experiment data [18], j has been modified as j0.12. is the maximum conductance of IMGC_Mfb (0.043 nS), and EMGC,Mfb is the reversal potential of MGCs (selected a value close to 0 mV) [21].

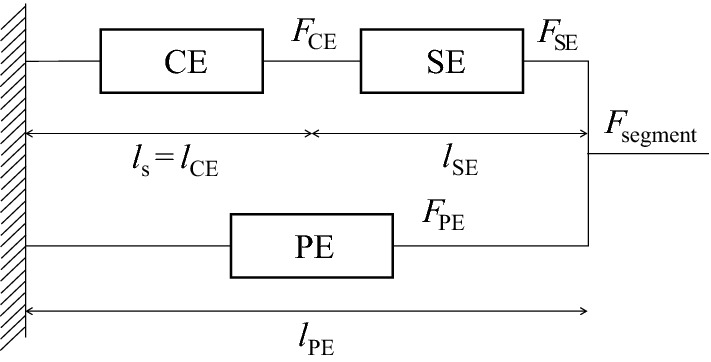

Mechanical behavior of a single segment

The mechanical behavior of a single segment in our model is based on the classical three-element rheological scheme [53, 54].

As shown in Fig. 6, active force (FCE) is generated by the contractile element (CE), and passive forces (FSE, FPE) are generated in a serial elastic element (SE) and a parallel elastic element (PE). Fsegment is the total force generated by the segment. The element lengths are lCE, lSE, and lPE. During mechanical equilibrium, FCE, Fsegment, and lPE are defined as

| 13 |

| 14 |

| 15 |

Fig. 6.

Three-element scheme to model mechanical behavior of a single segment

Simulation protocol

We performed single-cell simulations with constant sarcomere length (isosarcometric contraction) and constant applied force (isotonic contraction) to investigate the effects of ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb on myocyte mechanical properties.

Five groups were simulated sequentially: one atrial myocyte without Mfb coupling (Group 1), one atrial myocyte coupled to two Mfbs without ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb (Group 2), one atrial myocyte coupled to two Mfbs with INa_Mfb (Group 3), one atrial myocyte coupled to two Mfbs with ISAC and INa_Mfb (Group 4), and one atrial myocyte coupled to two Mfbs with ISAC, INa_Mfb, and IMGC_Mfb (Group 5).

First, simulations were carried out at a constant Ggap of 3 nS and a BCL of 1 s. Thereafter, the coupled system was paced with (1) BCLs from 0.1 to 2 s, (2) Ggap from 0.5 to 8 nS, and (3) number of coupled Mfbs from 1 to 8, to investigate the role of BCL, Ggap, and Mfbs in myocyte mechanical parameters. The maximum or minimum of FSE, FPE, Fsegment, lCE, lSE, and lPE at different BCL, Ggap, and Mfbs number were examined.

To ensure the coupled system reached steady-state, stimulation was repeated for 20 cycles. Results from the last cycle in each simulation were used for subsequent analyses. All state variables of the coupled model were updated by means of the forward Euler method. The time step was set to be 10 μs to ensure numerical accuracy and stability. More information on “Methods” is available in the Additional file 1.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- SAC

stretch-activated channel

- Mfb

myofibroblast

- MGC

mechano-gated channel

- Mfb–M

myofibroblast–myocyte

- VGSC

voltage-gated sodium channel

- AP

action potential

- EMC

electromechanical coupling

- MEF

mechanoelectrical feedback

- TRPM7

transient receptor potential cationic channel subfamily M member 7

- APD

duration of the action potential

- BCL

basic cycle length

- CE

contractile element

- SE

serial elastic element

- PE

parallel elastic element

Authors’ contributions

HZ prepared the manuscript in collaboration with the clinician (cardiologist) JZ. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This project is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81501557).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

We consent for the publication of this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing of interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12938-019-0723-5.

References

- 1.Trayanova NA, Boyle PM. Advances in modeling ventricular arrhythmias: from mechanisms to the clinic. Wiley Interdiscipl Rev Syst Biol Med. 2014;6(2):209–224. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang JH, Saucerman JJ. Computational models reduce complexity and accelerate insight into cardiac signaling networks. Circ Res. 2011;108(1):85–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaniboni M. Short-term action potential memory and electrical restitution: a cellular computational study on the stability of cardiac repolarization under dynamic pacing. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(3):e0193416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sato D, Dixon RE, Santana LF, Navedo MF. A model for cooperative gating of L-type Ca2+ channels and its effects on cardiac alternans dynamics. PLoS Comput Biol. 2018;14(1):e1005906. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Regazzoni F, Dede L, Quarteroni A. Active contraction of cardiac cells: a reduced model for sarcomere dynamics with cooperative interactions. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2018;17(6):1663–1686. doi: 10.1007/s10237-018-1049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dupuis LJ, Lumens J, Arts T, Delhaas T. Mechano-chemical interactions in cardiac sarcomere contraction: a computational modeling study. PLoS Comput Biol. 2016;12(10):e1005126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pfeiffer ER, Tangney JR, Omens JH, McCulloch AD. Biomechanics of cardiac electromechanical coupling and mechanoelectric feedback. J Biomech Eng. 2014;136(2):021007. doi: 10.1115/1.4026221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng T, Bett GC, Sachs F. Stretch-activated whole cell currents in adult rat cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278(2):H548–H557. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.2.H548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amar A, Zlochiver S, Barnea O. Mechano-electric feedback effects in a three-dimensional (3D) model of the contracting cardiac ventricle. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(1):e0191238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collet A, Bragard J, Dauby PC. Temperature, geometry, and bifurcations in the numerical modeling of the cardiac mechano-electric feedback. Chaos. 2017;27(9):093924. doi: 10.1063/1.5000710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohl P, Day K, Noble D. Cellular mechanisms of cardiac mechano-electric feedback in a mathematical model. Can J Cardiol. 1998;14(1):111–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeigler AC, Richardson WJ, Holmes JW, Saucerman JJ. Computational modeling of cardiac fibroblasts and fibrosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;93:73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mouton AJ, Ma Y, Rivera Gonzalez OJ, Daseke MJ, 2nd, Flynn ER, Freeman TC, Garrett MR, DeLeon-Pennell KY, Lindsey ML. Fibroblast polarization over the myocardial infarction time continuum shifts roles from inflammation to angiogenesis. Basic Res Cardiol. 2019;114(2):6. doi: 10.1007/s00395-019-0715-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tarbit E, Singh I, Peart JN, Rose’Meyer RB. Biomarkers for the identification of cardiac fibroblast and myofibroblast cells. Heart Fail Rev. 2019;24(1):1–15. doi: 10.1007/s10741-018-9720-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shibukawa Y, Chilton EL, Maccannell KA, Clark RB, Giles WR. K+ currents activated by depolarization in cardiac fibroblasts. Biophys J. 2005;88(6):3924–3935. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.054429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chilton L, Ohya S, Freed D, George E, Drobic V, Shibukawa Y, Maccannell KA, Imaizumi Y, Clark RB, Dixon IM, Giles WR. K+ currents regulate the resting membrane potential, proliferation, and contractile responses in ventricular fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288(6):H2931–H2939. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01220.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du J, Xie J, Zhang Z, Tsujikawa H, Fusco D, Silverman D, Liang B, Yue L. TRPM7-mediated Ca2+ signals confer fibrogenesis in human atrial fibrillation. Circ Res. 2010;106(5):992–1003. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.206771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chatelier A, Mercier A, Tremblier B, Theriault O, Moubarak M, Benamer N, Corbi P, Bois P, Chahine M, Faivre JF. A distinct de novo expression of Nav1.5 sodium channels in human atrial fibroblasts differentiated into myofibroblasts. J Physiol. 2012;590(17):4307–4319. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.233593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koivumäki JT, Clark RB, Belke D, Kondo C, Fedak PWM, Maleckar MMC, Giles WR. Na(+) current expression in human atrial myofibroblasts: identity and functional roles. Front Physiol. 2014;5:275. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li GR, Sun HY, Chen JB, Zhou Y, Tse HF, Lau CP. Characterization of multiple ion channels in cultured human cardiac fibroblasts. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(10):e7307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamkin A, Kirischuk S, Kiseleva I. Single mechano-gated channels activated by mechanical deformation of acutely isolated cardiac fibroblasts from rats. Acta Physiol. 2010;199(3):277–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El Chemaly A, Guinamard R, Demion M, Fares N, Jebara V, Faivre JF, Bois P. A voltage-activated proton current in human cardiac fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340(2):512–516. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yue L, Xie J, Nattel S. Molecular determinants of cardiac fibroblast electrical function and therapeutic implications for atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;89(4):744–753. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rohr S. Myofibroblasts in diseased hearts: new players in cardiac arrhythmias? Heart Rhythm. 2009;6(6):848–856. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashihara T, Haraguchi R, Nakazawa K, Namba T, Ikeda T, Nakazawa Y, Ozawa T, Ito M, Horie M, Trayanova NA. The role of fibroblasts in complex fractionated electrograms during persistent/permanent atrial fibrillation: implications for electrogram-based catheter ablation. Circ Res. 2012;110(2):275–284. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.255026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacCannell KA, Bazzazi H, Chilton L, Shibukawa Y, Clark RB, Giles WR. A mathematical model of electrotonic interactions between ventricular myocytes and fibroblasts. Biophys J. 2007;92(11):4121–4132. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.101410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDowell KS, Vadakkumpadan F, Blake R, Blauer J, Plank G, Macleod RS, Trayanova NA. Mechanistic inquiry into the role of tissue remodeling in fibrotic lesions in human atrial fibrillation. Biophys J. 2013;104(12):2764–2773. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhan H, Zhang J, Lin J, Han G. Effects of Na(+) current and mechanogated channels in myofibroblasts on myocyte excitability and repolarization. Comput Math Methods Med. 2016;2016:6189374. doi: 10.1155/2016/6189374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reinhardt JW, Gooch KJ. Agent-based modeling traction force mediated compaction of cell-populated collagen gels using physically realistic fibril mechanics. J Biomech Eng. 2014;136(2):021024. doi: 10.1115/1.4026179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Checa S, Rausch MK, Petersen A, Kuhl E, Duda GN. The emergence of extracellular matrix mechanics and cell traction forces as important regulators of cellular self-organization. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2015;14(1):1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10237-014-0581-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rouillard AD, Holmes JW. Coupled agent-based and finite-element models for predicting scar structure following myocardial infarction. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2014;115(2–3):235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fomovsky GM, Holmes JW. Evolution of scar structure, mechanics, and ventricular function after myocardial infarction in the rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298(1):H221–H228. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00495.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuijpers NH, ten Eikelder HM, Bovendeerd PH, Verheule S, Arts T, Hilbers PA. Mechanoelectric feedback leads to conduction slowing and block in acutely dilated atria: a modeling study of cardiac electromechanics. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292(6):H2832–H2853. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00923.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhan HQ, Xia L. Excitation-contraction coupling between human atrial myocytes with fibroblasts and stretch activated channel current: a simulation study. Comput Math Methods Med. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/238676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Franz MR, Burkhoff D, Yue DT, Sagawa K. Mechanically induced action potential changes and arrhythmia in isolated and in situ canine hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 1989;23(3):213–223. doi: 10.1093/cvr/23.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Isenberg G, Kazanski V, Kondratev D, Gallitelli MF, Kiseleva I, Kamkin A. Differential effects of stretch and compression on membrane currents and [Na+]c in ventricular myocytes. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2003;82(1–3):43–56. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6107(03)00004-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Putten S, Shafieyan Y, Hinz B. Mechanical control of cardiac myofibroblasts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;93:133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ, Galli A, Bochaton-Piallat ML, Gabbiani G. The myofibroblast: one function, multiple origins. Am J Pathol. 2007;170(6):1807–1816. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang H, Abhilash AS, Chen CS, Wells RG, Shenoy VB. Long-range force transmission in fibrous matrices enabled by tension-driven alignment of fibers. Biophys J. 2014;107(11):2592–2603. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harris AK, Stopak D, Wild P. Fibroblast traction as a mechanism for collagen morphogenesis. Nature. 1981;290(5803):249–251. doi: 10.1038/290249a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rouillard AD, Holmes JW. Mechanical regulation of fibroblast migration and collagen remodelling in healing myocardial infarcts. J Physiol. 2012;590(18):4585–4602. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.229484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fomovsky GM, Rouillard AD, Holmes JW. Regional mechanics determine collagen fiber structure in healing myocardial infarcts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52(5):1083–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Catterall WA, Goldin AL, Waxman SG. International Union of Pharmacology. XLVII. Nomenclature and structure–function relationships of voltage-gated sodium channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57(4):397–409. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kamkin A, Kiseleva I, Isenberg G, Wagner KD, Gunther J, Theres H, Scholz H. Cardiac fibroblasts and the mechano-electric feedback mechanism in healthy and diseased hearts. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2003;82(1–3):111–120. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6107(03)00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kamkin A, Kiseleva I, Lozinsky I, Scholz H. Electrical interaction of mechanosensitive fibroblasts and myocytes in the heart. Basic Res Cardiol. 2005;100(4):337–345. doi: 10.1007/s00395-005-0529-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herum KM, Lunde IG, McCulloch AD, Christensen G. The soft- and hard-heartedness of cardiac fibroblasts: mechanotransduction signaling pathways in fibrosis of the heart. J Clin Med. 2017;6(5):53. doi: 10.3390/jcm6050053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zlochiver S, Munoz V, Vikstrom KL, Taffet SM, Berenfeld O, Jalife J. Electrotonic myofibroblast-to-myocyte coupling increases propensity to reentrant arrhythmias in two-dimensional cardiac monolayers. Biophys J. 2008;95(9):4469–4480. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.136473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reed A, Kohl P, Peyronnet R. Molecular candidates for cardiac stretch-activated ion channels. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2014;2014(2):9–25. doi: 10.5339/gcsp.2014.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rog-Zielinska EA, Norris RA, Kohl P, Markwald R. The living scar-cardiac fibroblasts and the injured heart. Trends Mol Med. 2016;22(2):99–114. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maleckar MM, Greenstein JL, Giles WR, Trayanova NA. K+ current changes account for the rate dependence of the action potential in the human atrial myocyte. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297(4):H1398–H1410. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00411.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rice JJ, Jafri MS, Winslow RL. Modeling short-term interval-force relations in cardiac muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278(3):H913–H931. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.3.H913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rice JJ, Winslow RL, Hunter WC. Comparison of putative cooperative mechanisms in cardiac muscle: length dependence and dynamic responses. Am J Physiol. 1999;276(5 Pt 2):H1734–H1754. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.5.H1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hill AV. The heat of shortening and the dynamic constants of muscle. Proc R Soc Lond Ser B. 1938;126:136. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1938.0050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Solovyova O, Katsnelson L, Guriev S, Nikitina L, Protsenko Y, Routkevitch S, Markhasin V. Mechanical inhomogeneity of myocardium studied in parallel and serial cardiac muscle duplexes: experiments and models. Chaos Soliton Fract. 2002;13(8):1685–1711. doi: 10.1016/S0960-0779(01)00175-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim D. Novel cation-selective mechanosensitive ion channel in the atrial cell membrane. Circ Res. 1993;72(1):225–231. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.72.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Keener JP, Sneyd J. Mathematical physiology. New York: Springer; 1998. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.