Endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) are integrated retroviral elements within the human genome. Tokuyama et al. (1) recently published a computational tool, “ERVmap,” to analyze genome-wide, locus-specific expression of human ERVs. The authors found increased expression of 124 ERV loci in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), compared to controls, and 0 down-regulated loci. In contrast, our reanalysis of their data using a Bayesian reassignment algorithm, Telescope (2), detected only 23 ERV locations with significant differential expression (DE), including 4 loci with significantly lower expression. We found that the differences between the results could be due to methodological aspects of their analysis, including alignment ambiguity, ERV annotation, and failure to account for sequencing platform as a source of variance (3).

ERVmap does not adequately address the problem of alignment ambiguity, which occurs when sequencing reads align to multiple distinct genomic locations, a major challenge for quantifying expression of repetitive elements (4–7). The ERVmap pipeline aligns reads to the reference genome, allowing for multiple alignments per read, and then applies “very stringent filtering criteria to the mapped reads” (1, p. 12566). These heuristics effectively eliminate suboptimal alignments to the reference genome, but tend to discard data instead of identifying a location for each read. In contrast, Telescope uses a generative model of RNA-seq to reassign ambiguously mapped reads. The choice of annotation is likely to have a dramatic impact on transcriptomic quantification (8). The ERVmap annotation containing 3,220 ERV loci is limited compared to other ERV annotations; for example, current Telescope annotation considers 14,968 proviral-ERV elements across 60 subfamilies.

We reanalyzed the data from Tokuyama et al. (1) with Telescope, assigning ambiguously mapped reads, and compared results to those reported from ERVmap. Filtering, normalization, and DE testing were performed using DESeq2 (9). After initial analysis with the linear model used by Tokuyama et al. (1), we determined that the sequencing platform is an important source of variation and chose to include “platform” as a covariate.

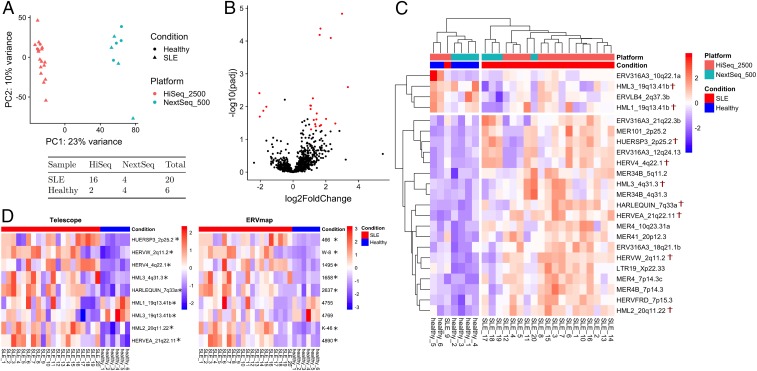

Our findings suggest that the majority of differentially expressed locations identified by Tokuyama et al. (1) are false positives (Fig. 1). We found that reassigning ambiguous reads, rather than filtering, allows better and more powerful use of the data. We identified 198,026 fragments mapping to our annotation, with 65% mapping to multiple locations. After reassigning reads using Telescope, only 0.02% of reads were discarded. We identified 19 ERV loci with significantly higher expression in patients with SLE and 4 loci with lower expression (Fig. 1 B and C). Of these 23 loci, over half (14) were not present in their annotation, while only 7 were DE in both analyses. Interestingly, we found that the greatest source of variance could be attributed to the sequencing platform (Fig. 1A). Testing for DE without including a platform covariate resulted in 83 DE ERVs, all of them overexpressed in SLE, suggesting that most DE ERVs identified by Tokuyama et al. (1) are not due to SLE status, but to sequencing platform.

Fig. 1.

Differential expression analysis. (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) of all genes and ERVs with normalized counts colored based on platform. The number of samples per platform is shown under the PCA plot. (B) Volcano plot depicting differentially expressed ERVs measured by Telescope. Red points represent differentially expressed ERVs. (C) Heatmap of differentially expressed ERVs. Red, higher expression; blue, lower expression. Normalized ERV counts were scaled to Z scores and the Euclidean distances calculated for hierarchical clustering. The complete linkage method was used for clustering. Highlighted loci (†) were also present in ERVmap annotation and are shown in D. (D) Overlapped differentially expressed ERVs between Telescope and ERVmap annotations. Asterisks indicate significantly differentially expressed ERV loci (padj < 0.05, log2 fold-change > 1.0) identified by each analysis. Left shows the normalized Z-score scaled values of Telescope. Right shows the matched annotations in ERVmap. Normalized Z-score scaled values are also illustrated.

In conclusion, ERVmap makes an important attempt to address the challenge of locus-specific ERV quantification but falls short in several ways. However, we agree that the role of ERV expression in SLE is an important area for continued research.

Acknowledgments

Funding, in part, is from NIH Grants AI076059 and CA206488.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The scripts and count matrices used to reproduce Fig. 1 and the analyses are available at https://github.com/LIniguez/Tokuyama_Analysis.

References

- 1.Tokuyama M., et al. , ERVmap analysis reveals genome-wide transcription of human endogenous retroviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 12565–12572 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bendall M. L., et al. , Telescope: Characterization of the retrotranscriptome by accurate estimation of transposable element expression. bioRxiv:398172 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conesa A., et al. , A survey of best practices for RNA-seq data analysis. Genome Biol. 17, 13 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Treangen T. J., Salzberg S. L., Repetitive DNA and next-generation sequencing: Computational challenges and solutions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 36–46 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li B., Ruotti V., Stewart R. M., Thomson J. A., Dewey C. N., RNA-Seq gene expression estimation with read mapping uncertainty. Bioinformatics 26, 493–500 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Criscione S. W., Zhang Y., Thompson W., Sedivy J. M., Neretti N., Transcriptional landscape of repetitive elements in normal and cancer human cells. BMC Genomics 15, 583 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin Y., Tam O. H., Paniagua E., Hammell M., TEtranscripts: A package for including transposable elements in differential expression analysis of RNA-seq datasets. Bioinformatics 31, 3593–3599 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao S., Zhang B., A comprehensive evaluation of ensembl, RefSeq, and UCSC annotations in the context of RNA-seq read mapping and gene quantification. BMC Genomics 16, 97 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Love M. I., Huber W., Anders S., Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]