Significance

Cancers associated with the human papillomavirus, including oropharyngeal, anal canal, cervical, and vulvar carcinomas, constitute about 4.5% of all solid tumors. In many cases, they can be readily cured with radiotherapy, which is the mainstay of treatment. HPV-associated cancers are more radiosensitive than HPV-negative cancers, but the mechanism of this radiosensitivity is unknown. Across all of oncology, HPV association is one of the only validated molecular biomarker of radiosensitivity. Here, we demonstrate that the HPV16 E7 oncoprotein alters DNA double-strand break repair pathways by promoting error-prone, microhomology-mediated end-joining and suppressing nonhomologous end-joining. These results characterize the molecular mechanism of this unique biomarker in cancer therapy and suggest therapeutic vulnerabilities.

Keywords: HPV, radiation, E7, microhomology-mediated end-joining, alternative end-joining

Abstract

Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) arising from aerodigestive or anogenital epithelium that are associated with the human papillomavirus (HPV) are far more readily cured with radiation therapy than HPV-negative SCCs. The mechanism behind this increased radiosensitivity has been proposed to be secondary to defects in DNA repair, although the specific repair pathways that are disrupted have not been elucidated. To gain insight into this important biomarker of radiosensitivity, we first examined genomic patterns reflective of defects in DNA double-strand break repair, comparing HPV-associated and HPV-negative head and neck cancers (HNSCC). Compared to HPV-negative HNSCC genomes, HPV+ cases demonstrated a marked increase in the proportion of deletions with flanking microhomology, a signature associated with a backup, error-prone double-strand break repair pathway known as microhomology-mediated end-joining (MMEJ). Then, using 3 different methodologies to comprehensively profile double-strand break repair pathways in isogenic paired cell lines, we demonstrate that the HPV16 E7 oncoprotein suppresses canonical nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) and promotes error-prone MMEJ, providing a mechanistic rationale for the clinical radiosensitivity of these cancers.

The human papillomavirus (HPV) is an oncogenic virus that has been long linked to multiple anogenital cancers including cervical cancer, anal cancer, penile cancer, and vulvar cancer (1). In the last 2 decades, it has become clear that HPV is responsible for a rapidly increasing proportion of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC), specifically oropharyngeal cancers (OPC) (2). The prognosis of HPV-associated OPC is markedly improved compared to HPV-negative OPC (3, 4), largely due to an improved response to chemoradiation. However, the underlying mechanisms responsible for this marked sensitivity to ionizing radiation (IR) and DNA damaging agents remain unknown.

Preclinical studies have demonstrated that HPV+ HNSCC cell lines are intrinsically more radiosensitive than their HPV− counterparts, suggesting that HPV infection plays a direct role in radiosensitivity (5, 6). Microhomology-mediated end-joining (MMEJ) is a double-strand break (DSB) repair pathway that may play a critical role in radiosensitivity (7, 8) as it is highly error prone and may lead to lethal repair events. MMEJ is thought to serve as a backup pathway that is activated by defects that occur in the major canonical nonhomologous end-joining (cNHEJ) or homologous recombination (HR) pathways (9), as has been demonstrated in HR-deficient breast and ovarian tumors (10). While multiple lines of evidence suggest that HPV oncoproteins interfere with the DNA damage response, the DSB repair pathways that are affected have yet to be clarified.

Defects in cNHEJ have been identified in multiple human cancers and are known to be highly radiosensitizing (11–16). RB1, the primary target of HPV E7, has been reported to play a direct role in cNHEJ through recruitment of XRCC5/6 (Ku70/80) to the sites of DSBs, suggesting a potential role for E7 in dysregulation of DSB repair (17). Furthermore, disruption of cNHEJ often results in a reciprocal increase in MMEJ and genomic sites of HPV viral integration in cervical and oropharyngeal cancers have been found to be highly enriched for microhomology, the defining hallmark of MMEJ, suggesting an association between HPV and MMEJ (18, 19).

In the current study, we demonstrate that HPV-associated tumors reflect genomic scars associated with frequent use of MMEJ. Furthermore, we find that HPV16-E7 expression alone promotes radiosensitivity and is primarily responsible for alterations in DSB repair pathway choice that underly these changes.

Results

HPV-Associated HNSCC Genomes Feature Deletions with Short Stretches of Microhomology.

In the absence of effective HR, there is increased use of backup DSB repair pathways that lead to increased translocations and deletions over the course of carcinogenesis, which can be quantified and recognized in tumor genomes using a computational algorithm called Large-scale State Transitions (LST) (20, 21). The LST score quantifies the number of genomic alterations consisting of a rejoining repair event of 2 DSBs at least 10 Mb apart in the genome. High LST scores in cancer genomes are associated with germ-line or somatic mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 as well as other HR genes (22–24). In addition, a characteristic base substitution pattern known as Signature 3 is also strongly associated with BRCA1/2 mutations and HR deficiency (25, 26). The Signature 3 pattern was empirically discovered and is readily distinguished from other base substitution patterns from aging, tobacco smoke, and the effect of APOBEC enzymes. Elevated LST and Signature 3 characterize tumors deficient in HR, including cancers with mutations in HR genes other than BRCA1/2 or cancers with nongenetic mechanisms of HR inactivation such as hypermethylation of the BRCA1 promoter (22, 23).

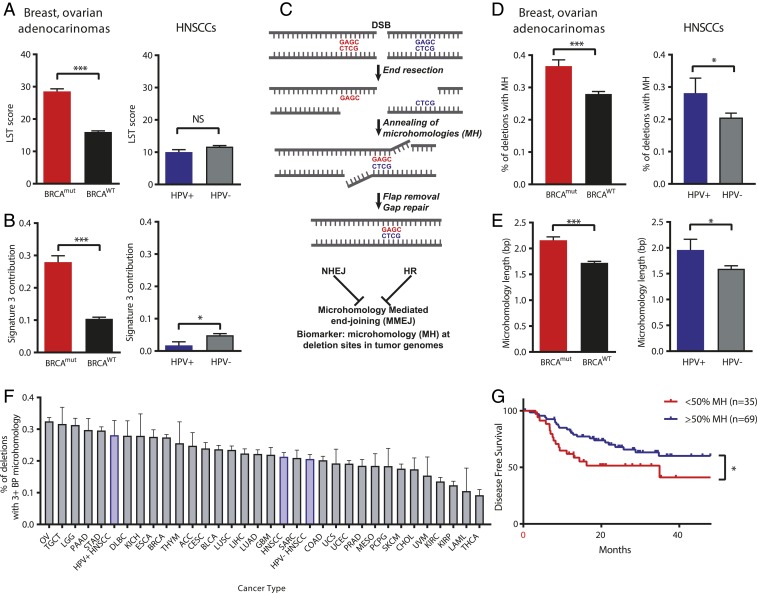

To characterize possible effects of HPV infection on DNA repair in human HNSCCs, we first profiled LST and Signature 3 scores in human cancer genomes sequenced as part of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project, comparing HPV+ and HPV− HNSCCs (Fig. 1 A and B). Cancers with biallelic BRCA1/2 mutations (BRCAmut) controls in breast and ovarian cancers demonstrate higher LST and Signature 3 scores, as expected, whereas HPV+ HNSCCs exhibit low LST scores and no difference from HPV− HNSCCs. Both HPV+ and HPV− HNSCCs also have very low Signature 3 scores and, in fact, HPV− HNSCCs exhibit higher mean Signature 3 scores. These data indicate that an HR deficiency is unlikely to explain the inherent radiosensitivity of HPV+ HNSCCs.

Fig. 1.

HPV-associated head and neck cancers are associated with increased utilization of microhomology at deletion breakpoints without signatures of homologous recombination deficiency. (A–E) The proportion of deletions with microhomology, LST scores, and contribution of genomic Stratton Signature 3 were measured in breast and ovarian cancers (n = 1,487) with or without biallelic BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation, and in HPV+ and HPV− head and neck cancers (n = 510). HPV+ head and neck cancers demonstrated an increase in microhomology usage (D) without an associated increase in LST score of Signature 3 contribution (A and B). (C) Schematic of MMEJ. (E) BRCA mutations and HPV positivity were associated with an increase in microhomology length in these tumors. (F) Whole exome sequencing data from all cancer types available in TCGA were analyzed for the presence of microhomology at mapped deletion sites, only deletions of 3+ bp in length were considered. The proportion of deletions with 3+ bp of microhomology across all cancer types is shown. (G) Disease-free survival (DFS) of TCGA HPV+ HNSCC cases classified by <50% of deletions containing MH and ≥50% deletions containing MH. Assessable cases defined as those having a least 1 characterized deletion with MH. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

An additional potential biomarker of HR deficiency is the predominance of microhomologous sequences on either side of small deletions (Fig. 1C). MMEJ is viewed as a backup end-joining pathway for both HR and NHEJ. In order to assess the role of MMEJ across multiple cancer types, we interrogated TCGA whole exome sequencing datasets across 32 cancer types (n = 10,271 tumors, SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Individual deletion breakpoints called by the TCGA project were assessed for the presence of microhomology flanking the breaksite, suggesting a DSB repair event mediated by MMEJ. Deletions with surrounding microhomology lengths of ≥3 base pairs were considered to be MMEJ associated, as it has been previously demonstrated that the central MMEJ factor polymerase theta (POLQ) mediates repair breakpoints with 3+ base pairs of microhomology (27). Ovarian cancers were found to have the highest proportion of microhomology-associated deletions (32.5%, Fig. 1F), consistent with a high percentage of ovarian cancers with HR defects (HRD) (28). Overall, HNSCCs were found to have an intermediate amount of microhomology (21.3% of deletions), although HPV+ HNSCCs demonstrated a higher proportion of deletions associated with 3+ bp of microhomology than HPV− HNC (HPV+ n = 77, 28.1% vs. HPV− n = 433, 20.6%, P = 0.04) shown in Fig. 1D. The mean number of base pairs of microhomology associated with breaksites is likewise increased in HPV+ HNSCC compared to HPV− HNSCC (Fig. 1E). Taken together, this genomic analysis suggests an increased utilization of MMEJ in HPV+ HNSCCs without the genomic hallmarks of HR deficiency (high LST and Signature 3).

Since microhomology (MH) at deletion sites is associated with radiosensitive HPV+ SCCs, we then examined whether MH associates with clinical outcomes (Fig. 1G and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Assessment of clinical outcomes in TCGA HPV+ HNSCC cases identified improved disease-free survival (DFS) in cases where >50% of deletions were associated with MH (3-y DFS: 60.1% in MH ≥ 50% group, 41.2% in MH < 50% group, P = 0.04, including only cases assessable with at least 1 deletion associated with MH). Furthermore, this effect was found to persist when including only patients who were treated with radiotherapy (3-y DFS: 54.5% in MH ≥ 50% group, 20.8% in MH < 50% group, P = 0.04), suggesting that a high proportion of deletions with associated MH is linked to radiosensitivity (SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

The high MH phenotype implies increased use of MMEJ in HPV+ HNSCCs. However, the expression of the central MMEJ factor POLQ is thought to vary widely across tissue types (29, 30), and the expression of POLQ is increased in some cancers requiring backup MMEJ (10). Thus, we examined expression levels of POLQ and other MMEJ factors in the TCGA RNA-sequencing (seq) datasets and expression of MMEJ factors is robust in HPV+ HNSCCs, indicating that MMEJ may be an active pathway (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

HPV16 E7 Increases Usage of Microhomology-Mediated End-Joining at DSBs.

As our genomic analysis identified an increase in MMEJ utilization, we then directly assessed the effect of HPV oncoprotein expression on DSB repair pathway choice. We employed previously described U2OS reporter cell lines designed to measure MMEJ (EJ2-GFP; ref. 31), cNHEJ (EJ5-GFP), and HR (DR-GFP) after a site-directed DSB is created by an expressed endonuclease I-SceI. We first measured the effects of each oncoprotein using expression plasmids for HPV oncoproteins that were transiently transfected into each reporter cell line, including E1, E2, E5, E6, and E7, and the percentage of GFP-positive cells was measured 72 h later by flow cytometry (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Compared to an empty vector control, only expression of HPV16 E7 resulted in a 42% increase in MMEJ activity (Fig. 2C, P = 0.005) and a 31% decrease in NHEJ activity (Fig. 2B, P = 0.002). Multiple HPV16 oncoproteins (E2, E5, E6, E7) up-regulated homologous recombination (Fig. 2A). A similar increase in MMEJ was observed when both E6 and E7 were expressed (Fig. 2C). Because defects in NHEJ are most likely to explain radiosensitivity, we focused on the effect of E7 on repair pathway choice.

Fig. 2.

HPV E7 protein expression down-regulates canonical nonhomologous end-joining (cNHEJ) and up-regulates MMEJ. (A–C) U2OS cells with integrated DSB repair reporter systems were transiently cotransfected with Isce1 restriction enzyme and plasmids expressing individual HPV16 oncoproteins (E1, E2, E5, E6, E7). The percentage of GFP-positive cells was measured 72 h following transfection by flow cytometry (n = 3+ repeats per condition). Cells expressing exogenous E7 oncoprotein showed an increase in HR and MMEJ but decreased cNHEJ. (D) Stable transfection of U2OS cells with the HPV16 E7 expression plasmid conferred significant reduction in pRB protein levels. (Lower) Survival curves based on clonogenic growth of U2OS cells with integrated EJ5 reporter system transfected with empty vector (red) and HPV16-E7 (blue). Curves represent the mean of 4 experiments. (E) Decrease in NHEJ activity measured by the percentage of GFP-positive cells in U2OS-EJ5 reporter cells with HPV16 E7 overexpression. (F) HR activity measured in DR-GFP cells showed increase in HR activity with E7 expression but not in the cells expressing mutant E7 C24G protein defective in pRb binding. (G) cNHEJ activity measured in U2OS EJ5-GFP cells showed down-regulation of cNHEJ activity with E7 expression but no difference in cells expressing E7 C24G. (H) MMEJ activity measured in U2OS EJ2-GFP cells showed up-regulation of MMEJ activity with E7 expression but no significant difference in cells expressing E7 C24G. At least 3 independent experiments were performed for each group. (I) Relationship between E7 mRNA expression in TCGA HPV+ HNSCC cases and percentage of deletions with MH. Cases partitioned into quartiles of increasing E7 expression levels *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; N.S., not significant.

Using a stably transfected U2OS clone expressing E7, we verified E7 expression with qPCR, demonstrated decreased Rb levels, and increased radiosensitivity (Fig. 2D) compared to a U2OS clone transfected with an empty vector. Cell cycle distribution and growth kinetics were identical with or without E7 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). These control experiments verify that E7 in our model sequesters and degrades Rb but does not alter cell cycle kinetics relative to the U2OS host. Using this fully characterized clone, we confirmed that E7 suppresses NHEJ while increasing MMEJ and HR (Fig. 2 E–H). We then found that the E7 effect on these repair pathway choices is dependent upon a residue within the E7 LXCXE domain that is required for binding to Rb (Fig. 2 F–H). The E7 C24G mutant with defective Rb binding LXCXE domain was chosen as it inactivates Rb as well as associated pocket proteins p107/p130 (32).

To further evaluate whether E7 is the likely driver of increased MMEJ, we again evaluated the HPV+ HNSCC cancer genomes and partitioned the cases into quartiles of low to high E7 expression by RNA-seq (33). This found a dose–response relationship between E7 expression and the MH phenotype (Fig. 2I).

HPV16 E7 Suppresses Formation of Phospho-DNA-PKcs Irradiation-Induced Foci.

Following recognition of a DSB by Ku70/80, the DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PKcs) associates with Ku70/80 at the break, autophosphorylates, and phosphorylates other factors to facilitate NHEJ. To further confirm the effect of E7 on cNHEJ in the setting of IR-mediated DNA damage with additional assays, we assessed the formation of pDNA-PKcs foci following IR at early time points when NHEJ is uniquely used. In a U2OS cell line, stable transfection with an HPV16 E7 expressing vector resulted in significant down-regulation of pRB (Fig. 2D) compared to vector control. Following 6 Gy of IR, the number of pDNA-PKcs foci per cell detected was significantly decreased in the E7-expressing cell line compared to empty vector (Fig. 3 A–C), supporting the notion that HPV16 E7 suppresses cNHEJ following IR-induced DNA damage.

Fig. 3.

Effect of E7 on cNHEJ in the setting of IR-mediated DNA damage. (A) Representative immunofluorescent images of phospho-DNA-PKcs foci at 30 and 60 min after radiation in U2OS cells stably transfected with an HPV16 E7-expressing vector or empty vector control. Green, phospho-DNA-PKcs foci; blue, DAPI staining. (B) The number of pDNA-pk foci per cell detected was significantly decreased in the E7-expressing cell line compared to the EV-expressing cell line. (C) Data from 3 independent experiments represented as fold change in foci per cell shows significant fold change in cells expressing E7 after 60 and 240 min after IR. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

At a Site-Directed DSB at an Endogenous Locus, HPV16 E7 Promotes Both MMEJ and HR at the Expense of cNHEJ Events.

To measure DSB repair pathway tradeoffs within an endogenous genomic locus, we used the Cas9 endonuclease to create a site-directed DSB at the AAVS1 locus, chosen because of its characterization as a “safe” genomic locus for integration. Cas9 creates a blunt-ended DSB, and repair events at the breaksite can be cataloged in a pool of cells using PCR amplification of a region surrounding the breaksite and massively parallel sequencing to quantify repair outcomes. To measure HR, we used a donor template containing 3 substitutions to reflect use of this pathway. NHEJ is measured with sequencing events with small (1–5) base-pair deletions, whereas MMEJ is quantified using sequencing events with large deletions and microhomology at the breaksite. All 3 pathways are thereby quantifiable in a single set of sequencing data in a single pool of cells (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

E7 expression shifts DNA DSB repair pathway choice toward MMEJ. (A) Schematic of DSBR-Seq Assay. The sequencing reads are classified into NHEJ (<5 bp deletion) in B, MMEJ (>5 bp deletion with at least 2 bp MH) in C, and HR (substitutions from HR donor) in D. The DNApk inhibitor Nu7741 was used at 1 μM concentration. (E) cNHEJ measured as a fraction of mutant reads with deletion sizes less than 5 bp. (F) E7 expression favors mutant reads with deletion sizes larger than 5 bp representing DSBs repaired by MMEJ. (G) E7 expression results in lower deletion frequency of small deletions near the DSB. Results represent the mean of 3 independent experiments ± the SEM. *P < 0.05.

As a control, the DNA-PKcs inhibitor Nu7441 was used in cells to show a decrease in small deletions (1–5 base pairs), reflective of NHEJ, an increase in larger deletions (>5 bp) with microhomology (≥2 bp), and an increase in HR (Fig. 4 B–D). Similar to the DNA-PKcs inhibitor, the E7 oncoprotein suppresses NHEJ, increasing both MMEJ and HR. When the profile of deletion sizes was examined, E7 suppressed a 1-bp deletion read without microhomology most significantly (Fig. 4E) and increased a 12-bp deletion with 5 bp of microhomology (Fig. 4F), corresponding to MMEJ. The distribution of deleted bases surrounding the breaksite was broadened away from the breaksite in the E7-expressed cells relative to the empty vector controls (Fig. 4G). Thus, 3 independent assays—cassette reporter assays, pDNApk foci, and comprehensive measurement of repair events at a site-directed break—each found a shift in repair events away from NHEJ analogous to the effect of a DNApkcs inhibitor.

Genomic DSB Repair Signatures of RB1 Loss.

As we identified pRB down-regulation in response to E7 expression as a driver of increased MMEJ and decreased cNHEJ, we assessed DNA DSB repair signatures in TCGA cases with loss of RB1 across all cancer types. Tumors with deep deletion copy number alterations (HOMDEL) of RB1 (n = 303 tumors) also demonstrated a substantial increase in microhomology at deletion breakpoints (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A and B). RB1 loss was also associated with a small but significant increase in LST score and Signature 3 contribution (SI Appendix, Fig. S6D). A simulation identified RB1 to be significantly associated with increased utilization of microhomology (P = 0.02) compared to loss of a set of 1,000 other random control genes (SI Appendix, Fig. S6C). Furthermore, across all cancer types, decreasing expression of pRB was associated with a progressive increase in microhomology utilization at deletion breakpoints (SI Appendix, Fig. S6E). Taken together, these data provide evidence that RB1 loss or suppression, outside of an effect of HPV, may also be associated with decreased utilization of cNHEJ and increased MMEJ.

Discussion

HPV positivity represents a biomarker of paramount clinical support as SCCs of the oropharynx (3), cervix (34), vulva, and anal canal (35, 36) each are more radiosensitive than their non-HPV SCC counterparts. Thus, understanding the mechanism behind HPV-associated radiosensitivity provides insight with broad implications.

There have been multiple purported mechanisms that are thought to underlie the radiosensitivity of HPV-associated tumors. The intrinsic cellular radiosensitivity that has been observed in HPV-positive HNSCC cell lines compared to HPV-negative cell lines (6) suggests that differences in the DNA damage response may be responsible, as opposed to microenvironmental or immune-related mechanisms. HPV-positive HNSCCs have been found to be deficient in TGF-β signaling, which has been shown to be associated with suppression of HR and an increase in alternative end-joining (37). Despite the suppression of TP53 by E6, radiation-induced activation of the remaining low level of p53 has been implicated in radiation sensitivity of HPV-positive cell lines (6). Finally, E6 has also been reported to impair HR while E7 had no effect (38) and nonisogenic comparisons of 1 HPV− and 2 HPV+HNSCC cell lines have suggested HPV-associated defects in NHEJ (39) or HR (39, 40) or both (39). However, when larger cell line panels of HPV+ (n = 6) and HPV− HNSCC (n = 5) cell lines were compared, no difference in cisplatin sensitivity has been noted, which is a surrogate for HR efficiency (41). To deconvolve these observations on DSB repair, we measured all 3 major DSB repair pathways (NHEJ, HR, and MMEJ) in 3 separate assay systems and found consistent E7-mediated suppression of NHEJ and promotion of MMEJ, which matches human-level evidence in HPV-associated cancer genomes.

Abnormal end-joining, thought to be mediated by MMEJ, has previously been reported in HPV immortalized and HNSCC cell lines (42) and E7 specifically has been linked to effects on DSB repair (43). Like previous reports, we found that E7 alone is profoundly radiosensitizing and is the dominant factor behind DNA DSB repair pathway deficits, namely a 30–50% suppression of NHEJ events. These missing NHEJ repair events are transferred to both increased MMEJ and increased HR events. These pathway shifts were not explained by cell cycle distribution shifts. The E7-induced pathway shifts from NHEJ to error-prone MMEJ are similar to what is observed with DNA-PKcs inhibition, which is radiosensitizing in cell line and animal models and, thus, could also explain the radiosensitivity of HPV-associated squamous cell carcinomas.

As E6/E7 expression are early events in carcinogenesis of HPV-associated cancers, the subsequent effects of these genes can be measured in the pattern of deletions in cancer genomes. In HPV-associated HNSCC genomes, we find an overrepresentation of microhomology at deletion sites compared to HPV− HNSCC, indicating an overreliance on MMEJ. However, we did not find other genomic signatures of HR deficiency such as the Stratton 3 substitution pattern or the LST rearrangement score. These observations support our preclinical observations of an increased use of MMEJ that appears to result remarkably from a reciprocal response to NHEJ suppression as opposed to HRD.

The etiologic reason why the human papillomavirus suppresses NHEJ is unknown. It could be a byproduct of degradation of Rb, which is described to have a direct role in NHEJ by mediating recruitment of Ku complexes to DSBs (17). However, it could also be that increased usage of MMEJ promotes viral integration and there is a reported abundance of microhomology at sites of tumor-HPV viral genome interfaces (18, 19). In addition, the Rb–E2F interaction reduces expression of key HR and MMEJ genes in senescent G0 cells, an effect that is reversed by HPV16 E7 (44). We find that an E7 mutant deficient in Rb binding does not lead to suppression of NHEJ or promotion of MMEJ, indicating that the mechanism likely involves Rb directly.

These findings have important clinical implications for the management of HPV-associated and other cancers. Biomarkers of NHEJ suppression or MMEJ overutilization may assist in personalization of therapy by characterizing sensitivity of tumors to IR or other DNA damaging agents for deescalation or escalation of current treatments (i.e., chemoradiation treatment for HPV+ HNSCC and urogenital cancers). In addition, this work provides a rationale for exploration of pharmacologic inhibition of MMEJ factors in HPV-associated cancers.

Materials and Methods

General Methods.

All primers, plasmids, and reagents used in this study are cataloged in SI Appendix, Tables S1 and S3. Routine methods regarding cell culture, transfection, Western blots, quantitative PCR, cell growth, cassette reporter assays, pDNA-PKcs immunofluorescence, and clonogenic survival assays are described in detail in SI Appendix.

Genomic Analyses of Homologous Recombination Deficiency and Microhomology Analyses.

LST and Signature 3 were calculated as per methods previously reported (22). To determine microhomology at deletion sites, deletions annotated within the TCGA.maf files were analyzed using a custom algorithm following the steps outlined in SI Appendix, Fig. S1. Additional information noted in SI Appendix.

Cas9 Assay.

To quantify NHEJ, MMEJ, and HR at an endogenous breaksite, a Cas9 and gRNA expression plasmid and a donor template oligonucleotide was transfected into U2OS cells with and without E7 expressed. A PCR product surrounding the breaksite was sequenced using Illumina-based NGS technology, and the pattern of deletions at the breaksite was analyzed and quantified according to methods described within SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in the paper was supported by a research grant from the Society of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (to D.S.H.) and in part by Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA008748 of the NIH/National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Competing interest statement: S.S.H. and D.S.H. are listed as inventors on a provisional patent filed by their institution related to the method used in Fig. 4. There are no licenses or royalties.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1906120116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Van Dyne E. A., et al. , Trends in human papillomavirus-associated cancers–United States, 1999-2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 67, 918–924 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaturvedi A. K., Epidemiology and clinical aspects of HPV in head and neck cancers. Head Neck Pathol. 6 (suppl. 1), S16–S24 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ang K. K., et al. , Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 24–35 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leeman J. E., et al. , Patterns of treatment failure and postrecurrence outcomes among patients with locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma after chemoradiotherapy using modern radiation techniques. JAMA Oncol. 3, 1487–1494 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rieckmann T., et al. , HNSCC cell lines positive for HPV and p16 possess higher cellular radiosensitivity due to an impaired DSB repair capacity. Radiother. Oncol. 107, 242–246 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimple R. J., et al. , Enhanced radiation sensitivity in HPV-positive head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 73, 4791–4800 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kötter A., et al. , Inhibition of PARP1-dependent end-joining contributes to Olaparib-mediated radiosensitization in tumor cells. Mol. Oncol. 8, 1616–1625 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goff J. P., et al. , Lack of DNA polymerase theta (POLQ) radiosensitizes bone marrow stromal cells in vitro and increases reticulocyte micronuclei after total-body irradiation. Radiat. Res. 172, 165–174 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frit P., Barboule N., Yuan Y., Gomez D., Calsou P., Alternative end-joining pathway(s): Bricolage at DNA breaks. DNA Repair (Amst.) 17, 81–97 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ceccaldi R., et al. , Homologous-recombination-deficient tumours are dependent on Polθ-mediated repair. Nature 518, 258–262 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bentley J., et al. , Papillary and muscle invasive bladder tumors with distinct genomic stability profiles have different DNA repair fidelity and KU DNA-binding activities. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 48, 310–321 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bentley J., Diggle C. P., Harnden P., Knowles M. A., Kiltie A. E., DNA double strand break repair in human bladder cancer is error prone and involves microhomology-associated end-joining. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 5249–5259 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaymes T. J., Mufti G. J., Rassool F. V., Myeloid leukemias have increased activity of the nonhomologous end-joining pathway and concomitant DNA misrepair that is dependent on the Ku70/86 heterodimer. Cancer Res. 62, 2791–2797 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newman E. A., et al. , Alternative NHEJ pathway components are therapeutic targets in high-risk neuroblastoma. Mol. Cancer Res. 13, 470–482 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCormick A., et al. , Ovarian cancers harbor defects in nonhomologous end joining resulting in resistance to rucaparib. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, 2050–2060 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polkinghorn W. R., et al. , Androgen receptor signaling regulates DNA repair in prostate cancers. Cancer Discov. 3, 1245–1253 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook R., et al. , Direct involvement of retinoblastoma family proteins in DNA repair by non-homologous end-joining. Cell Rep. 10, 2006–2018 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parfenov M., et al. ; Cancer Genome Atlas Network , Characterization of HPV and host genome interactions in primary head and neck cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 15544–15549 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu Z., et al. , Genome-wide profiling of HPV integration in cervical cancer identifies clustered genomic hot spots and a potential microhomology-mediated integration mechanism. Nat. Genet. 47, 158–163 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abkevich V., et al. , Patterns of genomic loss of heterozygosity predict homologous recombination repair defects in epithelial ovarian cancer. Br. J. Cancer 107, 1776–1782 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Popova T., et al. , Ploidy and large-scale genomic instability consistently identify basal-like breast carcinomas with BRCA1/2 inactivation. Cancer Res. 72, 5454–5462 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riaz N., et al. , Pan-cancer analysis of bi-allelic alterations in homologous recombination DNA repair genes. Nat. Commun. 8, 857 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mutter R. W., et al. , Bi-allelic alterations in DNA repair genes underpin homologous recombination DNA repair defects in breast cancer. J. Pathol. 242, 165–177 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manié E., et al. , Genomic hallmarks of homologous recombination deficiency in invasive breast carcinomas. Int. J. Cancer 138, 891–900 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alexandrov L. B., et al. ; Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative; ICGC Breast Cancer Consortium; ICGC MMML-Seq Consortium; ICGC PedBrain , Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 500, 415–421 (2013). Erratum in: Nature502, 258 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nik-Zainal S., et al. , Landscape of somatic mutations in 560 breast cancer whole-genome sequences. Nature 534, 47–54 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kent T., Chandramouly G., McDevitt S. M., Ozdemir A. Y., Pomerantz R. T., Mechanism of microhomology-mediated end-joining promoted by human DNA polymerase θ. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22, 230–237 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elvin J. A., Chura J., Gay L. M., Markman M., Comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) of ovarian clear cell carcinomas (OCCC) identifies clinically relevant genomic alterations (CRGA) and targeted therapy options. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 20, 62–66 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawamura K., et al. , DNA polymerase theta is preferentially expressed in lymphoid tissues and upregulated in human cancers. Int. J. Cancer 109, 9–16 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seki M., Marini F., Wood R. D., POLQ (Pol theta), a DNA polymerase and DNA-dependent ATPase in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 6117–6126 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bennardo N., Cheng A., Huang N., Stark J. M., Alternative-NHEJ is a mechanistically distinct pathway of mammalian chromosome break repair. PLoS Genet. 4, e1000110 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Demers G. W., Espling E., Harry J. B., Etscheid B. G., Galloway D. A., Abrogation of growth arrest signals by human papillomavirus type 16 E7 is mediated by sequences required for transformation. J. Virol. 70, 6862–6869 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chakravarthy A., et al. , Human papillomavirus drives tumor development throughout the head and neck: Improved prognosis is associated with an immune response largely restricted to the oropharynx. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 4132–4141 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodríguez-Carunchio L., et al. , HPV-negative carcinoma of the uterine cervix: A distinct type of cervical cancer with poor prognosis. BJOG 122, 119–127 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mai S., et al. , Prognostic relevance of HPV infection and p16 overexpression in squamous cell anal cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 93, 819–827 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meulendijks D., et al. , HPV-negative squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal is unresponsive to standard treatment and frequently carries disruptive mutations in TP53. Br. J. Cancer 112, 1358–1366 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Q., et al. , Subjugation of TGFβ signaling by human papilloma virus in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma shifts DNA repair from homologous recombination to alternative end joining. Clin. Cancer Res. 24, 6001–6014 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wallace N. A., et al. , High-risk alphapapillomavirus oncogenes impair the homologous recombination pathway. J. Virol. 91, e01084-17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weaver A. N., et al. , DNA double strand break repair defect and sensitivity to poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibition in human papillomavirus 16-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 6, 26995–27007 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dok R., et al. , p16INK4a impairs homologous recombination-mediated DNA repair in human papillomavirus-positive head and neck tumors. Cancer Res. 74, 1739–1751 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Busch C. J., et al. , Similar cisplatin sensitivity of HPV-positive and -negative HNSCC cell lines. Oncotarget 7, 35832–35842 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shin K. H., et al. , Abnormal DNA end-joining activity in human head and neck cancer. Int. J. Mol. Med. 17, 917–924 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park J. W., et al. , Human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein causes a delay in repair of DNA damage. Radiother. Oncol. 113, 337–344 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collin G., Huna A., Warnier M., Flaman J. M., Bernard D., Transcriptional repression of DNA repair genes is a hallmark and a cause of cellular senescence. Cell Death Dis. 9, 259 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.