Significance

Members of the Hsp40/DnaJ family are cochaperones of the Hsp70 cycle and, additionally, act independently to prevent protein aggregation. DNAJB6b inhibits amyloid formation but has eluded detailed structural analysis due to its polydisperse oligomeric nature. Here, using a predominantly monomeric deletion variant, we unravel the solution structure and dynamics of DNAJB6b by NMR. DNAJB6b consists of 2 domains, a Hsp70-binding J domain and a substrate-binding C-terminal domain, that tumble almost independently of each other. Transient (millisecond time scale) intramolecular interactions are observed between the 2 domains, as well as intermolecular interactions between the C-terminal domains resulting in the formation of large oligomers. The results provide insights into regulation of the Hsp70 cycle by Hsp40 and the mechanism of antiaggregation.

Keywords: Hsp40/Hsp70 regulation, excited states, NMR relaxation, interdomain motions, oligomerization

Abstract

J-domain chaperones are involved in the efficient handover of misfolded/partially folded proteins to Hsp70 but also function independently to protect against cell death. Due to their high flexibility, the mechanism by which they regulate the Hsp70 cycle and how specific substrate recognition is performed remains unknown. Here we focus on DNAJB6b, which has been implicated in various human diseases and represents a key player in protection against neurodegeneration and protein aggregation. Using a variant that exists mainly in a monomeric form, we report the solution structure of an Hsp40 containing not only the J and C-terminal substrate binding (CTD) domains but also the functionally important linkers. The structure reveals a highly dynamic protein in which part of the linker region masks the Hsp70 binding site. Transient interdomain interactions via regions crucial for Hsp70 binding create a closed, autoinhibited state and help retain the monomeric form of the protein. Detailed NMR analysis shows that the CTD (but not the J domain) self-associates to form an oligomer comprising ∼35 monomeric units, revealing an intricate balance between intramolecular and intermolecular interactions. The results shed light on the mechanism of autoregulation of the Hsp70 cycle via conserved parts of the linker region and reveal the mechanism of DNAJB6b oligomerization and potentially antiaggregation.

Molecular self-assembly is central to both the function of a wide range of multimeric and oligomeric proteins and the malfunction of others. Kinetically trapped, misfolded, or partially folded states, either on or off pathway to the native state, show an increased propensity to aggregate into amorphous assemblies or ordered amyloid fibrils leading to a wide range of human pathologies (1). Although the exact nature of the cytotoxic species has not been fully established, it has been hypothesized that soluble oligomers and aggregates that form during the transition from the native state to fibrils are responsible for cell death (2–5). Consequently, ensuring that proteins fold correctly and remain folded in their functional form and that aggregated forms are disaggregated and removed is critical for the survival of all living cells. Molecular chaperones are the key players of the proteostasis network that serves to maintain the proteome in a functional state (6–8). One of the most important constituents of the chaperone network is the ubiquitous DnaK (Hsp70)/DnaJ (Hsp40) system, which participates in a broad array of processes that are critical for maintaining cell integrity (9, 10).

The DnaJ chaperones are multidomain proteins (Fig. 1A): the C-terminal domain(s) (CTD) of DnaJ is thought to recognize and deliver misfolded substrates to DnaK; the N-terminal J domain (JD) binds to DnaK via a conserved His-Pro-Asp (HPD) sequence resulting in enhancement of the ATPase activity of DnaK (11–13). The flexible linker connecting the JD and CTD domains has been shown to be critical for the specificity of the DnaJ–DnaK interaction and has also been implicated in substrate binding (14–16). The mechanistic and structural details of how the flexible linker of DnaJ modulates DnaK binding and regulates the entire Hsp70/Hsp40 cycle remains elusive even in light of the recent crystal structure of DnaJ fused to DnaK (12).

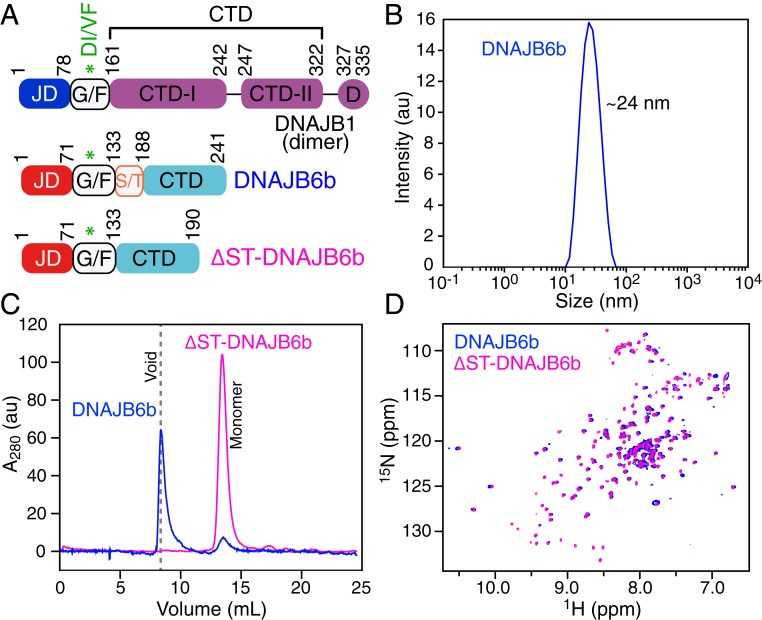

Fig. 1.

Characterization of DNAJB6b and the ΔST-DNAJB6b deletion mutant. (A) Domain architecture of the canonical isoform DNAJB1 and DNAJB6b, highlighting the J domain (JD), the flexible G/F linker, the C-terminal domains (CTDx), and the dimerization domain (D). DNAJB6b lacks the CTD-II and dimerization domains and has a low-complexity S/T region immediately N-terminal to the CTD domain. (B) Dynamic light scattering profile of 60 μΜ DNAJB6b. (C) Analytical size exclusion chromatography profiles of 100 μΜ DNAJB6b (blue) and ΔST-DNAJB6b (lilac). (D) Overlay of the TROSY 1H-15N HSQC spectra of 2H/15N-labeled DNAJB6b (blue) and ΔST-DNAJB6b (lilac) recorded at 600 MHz and 25 °C.

The DnaJ superfamily is one of the most diverse chaperone families, playing a multifaced role in maintaining proteostasis that extends beyond a simple delivery system to DnaK (9, 17). The canonical isoform (DNAJB1) of the class II DnaJ family is considered to be the one of the main DnaK cochaperones (9). In addition to the conserved JD domain, DNAJB1 contains 2 C-terminal β-sandwich domains (CTD-I and CTD-II) and a dimerization C-terminal helix domain (D) that acts as a hinge to create a Y-shaped dimer (18) (Fig. 1A). Another member of the class II family, DNAJB6, the focus of the current paper, has recently been shown to be a highly efficient inhibitor of aggregation of poly-glutamine containing proteins and amyloid β both in vivo and in vitro, in a manner that is independent of DnaK (19–21). In addition, DNAJB6b has been implicated in the regulation of breast cancer tumor growth and metastasis through interaction with various cell growth regulators (22). DNAJB6b consists of a highly conserved JD domain and a single CTD domain but lacks a dimerization domain (18, 23–26) (Fig. 1A). The linker region between the JD and CTD domains contains a low-complexity S/T domain with numerous conserved Ser and Thr residues, deletion of which reduces the substochiometric antiaggregation activity of DNAJB6b but does not completely abolish inhibition of fibril formation (21, 25). Structural insights into DNAJB6b itself and the manner in which DNAJB6b impedes aggregation are limited since there is no high-resolution structure of the complete protein.

DNAJB6b presents a challenge for structural studies since the wild-type form polymerizes to form large oligomers (25). To circumvent this problem and probe the structure and conformational dynamics of DNAJB6b in solution using NMR, we have made use of a construct that largely suppresses oligomer formation without perturbing the structure of the monomer. We show that a highly conserved region in the previously thought flexible linker forms a stable α helix that interacts with the JD domain, using the same interface as DnaK. The NMR data reveal that DNAJB6b is a highly flexible multidomain protein that exists predominantly in an open form. Paramagnetic relaxation enhancement and relaxation dispersion measurements, however, show that the JD and CTD domains undergo transient interdomain interactions to form a sparsely populated closed state on the millisecond time scale that presumably stabilizes the monomeric species. In addition, relaxation-based NMR studies show that the CTD domain, but not the JD domain, self-associates, suggesting an intricate equilibrium between the major, NMR observable, monomeric open species and sparsely populated monomeric closed and oligomeric states. These results provide insights into regulation of the DnaK cycle by DnaJ that is crucial for maintaining proteostasis and the mechanism whereby DNAJB6b recognizes substrates and inhibits their aggregation.

Results and Discussion

The ΔST Deletion Mutant Is a Good Mimic for Monomeric DNAJB6b in Solution.

DNJAB6b represents a challenging target for structural characterization due to the fact that it exists as a heterogeneous pool of species ranging in size from a 27-kDa monomer to an ∼1-MDa oligomer (with an average particle size of ∼24 nm) as shown by dynamic light scattering (Fig. 1B) and analytical size exclusion chromatography (Fig. 1C). Deletion of the S/T region (residues 132 to 183; Fig. 1A) to generate the ΔST deletion mutant (ΔST-DNAJB6b) results in a protein construct that is predominantly monomeric in solution (Fig. 1C). Despite the fact that wild-type DNAJB6b is a large oligomeric protein, we were able to record a transverse relaxation optimized (TROSY) 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) correlation spectrum (albeit with low sensitivity), suggesting that DNAJB6b oligomers are in exchange with monomers, consistent with previous reports (27). The cross-peaks in a 1H-15N correlation spectrum provide a fingerprint of a protein’s structure. Since the TROSY 1H-15N HSQC spectra of wild-type DNAJB6b and the ΔST-DNAJB6b deletion mutant overlay almost perfectly (Fig. 1D), one can conclude that deletion of the S/T region, while perturbing oligomer formation, does not affect the structure of the monomer. We therefore went on to perform a detailed NMR characterization of the structure and dynamics of the ΔST-DNAJB6b deletion mutant in solution.

The ΔST-DNAJB6b Deletion Mutant Is Dynamic.

The 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of protonated ΔST-DNAJB6b suffers from a relatively large dynamic range of linewidths and poor resolution of 1HN/15N cross-peaks for α-helical and flexible residues whose resonances are located in the middle of the 1HN region of the spectrum (centered around ∼8.0 ppm). Deuteration of the nonexchangeable protons solves both problems to a large extent, yielding a high-quality 1H-15N TROSY-HSQC spectrum (Fig. 1D) and allowing assignment of the backbone resonances using standard triple resonance techniques (28).

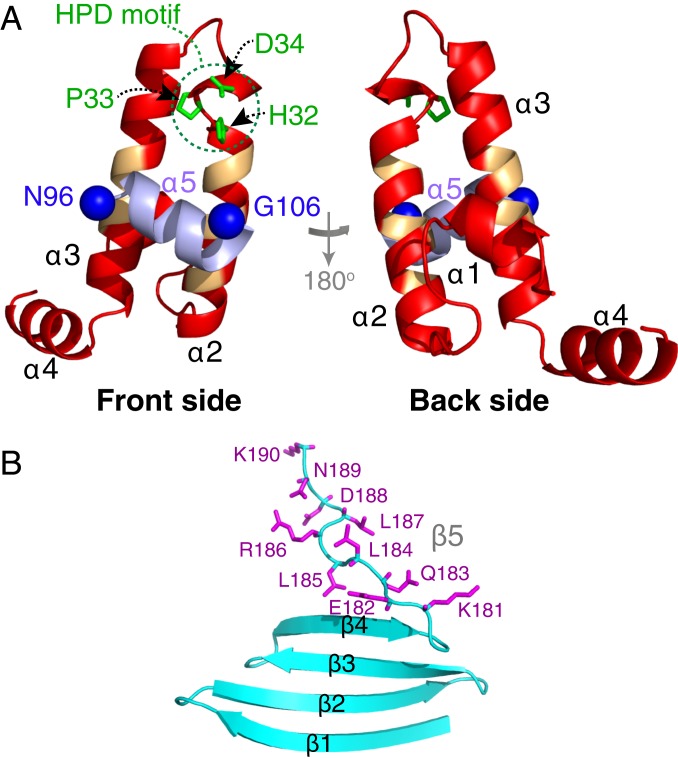

The secondary structure of ΔST-DNAJB6b is readily derived from the assigned backbone (13Cα, 13Cβ, 13C′, 15N, and 1HN) shifts using the program TALOS-N (29). The N-terminal region from residues 1 to 70 comprises 4 α helices (α1 to α4) (Fig. 2A), consistent with solution structures of isolated JD domains (23, 24). The presence of characteristic i + 3 and i + 4 HN-HN nuclear Overhauser enhancements (NOEs) further serves to delineate the beginning and end of the helices. The CTD domain consists of 5 β strands (β1 to β5) (Fig. 2A), in contrast to the canonical DNAJB1 isoform that has 2 6-stranded β-sandwich domains (CTD-I and CTD-II; Fig. 1A). The β-strand propensity is reduced toward the C terminus both in terms of β-strand length and probability (Fig. 2A). Indeed, although we could detect strong long-range HN-HN NOEs that connect strands β1, β2, β3, and β4, such NOEs were not observed between strands β4 and β5, suggesting that strand β5 (residues 181 to 187), although possessing a propensity to form a β strand, may be quite dynamic in solution. We further note that 1HN/15N cross-peaks for residues in the CTD domain show increased linewidths, a phenomenon that is even more pronounced in the full-length DNAJB6b construct (Fig. 1D, blue), characteristic of dynamics on the fast to intermediate chemical shift time scale. Interestingly, residues 98 to 104, located in the middle of the linker region (Fig. 1A) and containing the conserved Asp-Ile/Val-Phe (DI/VF with Val at position 100 in DNAJB6b) sequence motif, form a stable α helix (α5) based on both backbone chemical shifts and NOE data.

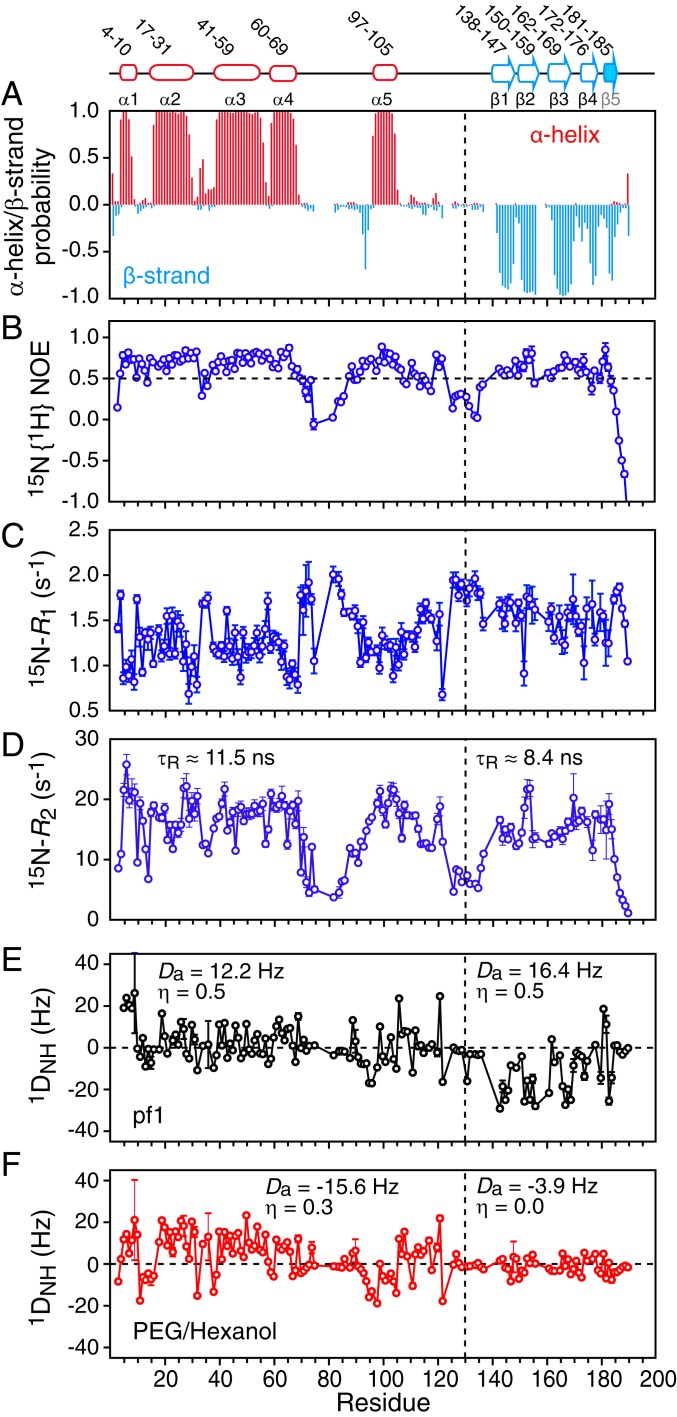

Fig. 2.

NMR characterization of ΔST-DNAJB6b. (A) TALOS-derived secondary structure (α helix in red and β strand in cyan) probability derived from the backbone 13Cα, 13Cβ, 13C′, 15N, and 1HN chemical shifts. The 15N relaxation data: (B) 15N{1H} heteronuclear NOE, (C) 15N-R1, and (D) 15N-R2. The 15N-R2 values were calculated from 15N-R1ρ values recorded with a 1.5-kHz spin lock field after correction for 15N-R1. Backbone amide (1DNH) residual dipolar coupling (RDC) data collected in 2 different alignment media: (E) 15 mg/mL phage pf1 and (F) 4.2% (vol/vol) polyethylene glycol/hexanol. The values of the magnitude of the principal component of the alignment tensor (Da) and the rhombicity (η) were determined from the distribution of RDCs using a maximum likelihood method (35, 36). The relaxation and RDC data were recorded at 600 and 800 MHz, respectively, on 120 μΜ 2H/15N-labeled ΔST-DNAJB6b samples at 25 °C.

The 15N-R1, 15N-R2, and heteronuclear 15N{1H} NOE data (Fig. 2 B–D) indicate that residues 70 to 96 and 106 to 133 in the G/F linker region (but excluding helix α5) and the C terminus (residues 185 to 190) are highly flexible with 15N{1H} NOE values below 0.5. Further, the 15N relaxation data (Fig. 1 B–D) show that the average <15N-R1> and <15N-R2> values for the JD and CTD domains are significantly different at the protein concentration (120 μΜ) used in these experiments. The effective rotational correlation time (τR) for the 2 domains, estimated from the 15N-R1/R2 ratios, is 11.5 and 8.4 ns for the JD and CTD domains, respectively, indicating that the 2 domains likely reorient semiindependently of one another in solution.

Solution Structure of ΔST-DNAJB6b.

To define the relative orientations between the secondary structure elements delineated by the chemical shift data, we collected backbone amide 1DHN residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) (30) in 2 different alignment media (phage pf1 and a polyethylene glycol [PEG]/hexanol mixture) (Fig. 2 E and F, respectively) (31, 32). Several features of the RDC profiles are noteworthy. First, helices 2 to 4 display a characteristic dipolar wave (33), which is reduced for helix 1, suggesting that the axis of the latter lies approximately parallel to the z axis of the alignment tensor. Second, the RDC values for residues 70 to 96 and 106 to 133 within the G/F linker region are close to 0, indicative of intrinsic disorder. Third, the magnitude of the RDCs measured for the CTD domain are dramatically reduced relative to those of the JD domain in PEG/hexanol (Fig. 2F), but not in phage pf1 (Fig. 2E), suggesting very different alignment tensors for the JD and CTD domains in PEG/hexanol. Estimation of the magnitude of the principal component (Da) and rhombicity (η) of the alignment tensor from the distribution of RDC values (34), using a maximum likelihood method (35, 36), yields very different values of Da and η in PEG/hexanol for the JD (−15.6 Hz and 0.3, respectively) and CTD (−3.9 Hz and 0, respectively) domains, diagnostic of the presence of medium- to large-scale interdomain motion (37). Further, the RDCs for helix 5 are fully consistent with the Da and η values of the JD domain (helices 1 to 4) but not the CTD domain, indicating that helix 5, located in the middle of the G/F linker region, actually reorients with the JD domain but not the CTD domain and hence should be considered as part of the JD domain.

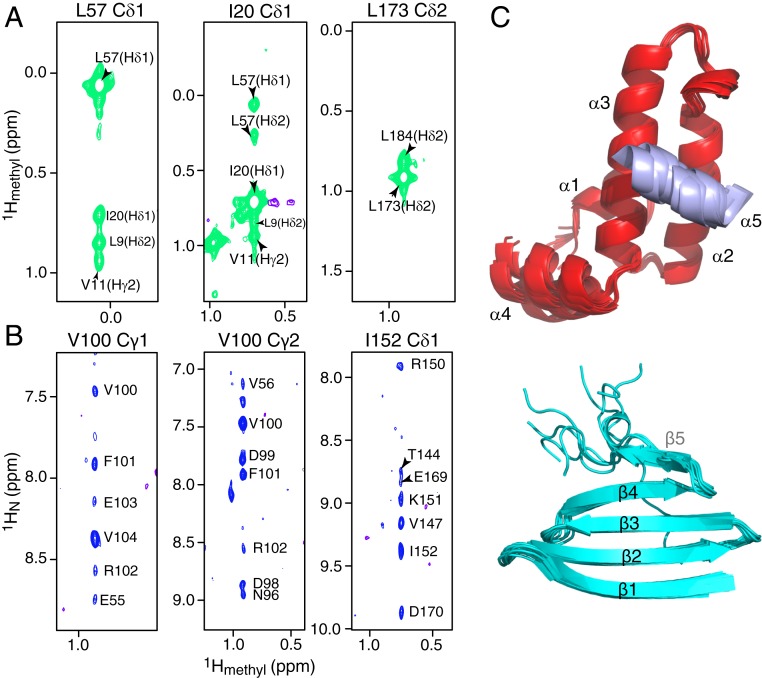

Although the RDC data provide orientational restraints on the angles between secondary structure elements, the RDCs alone are insufficient to position the secondary structure elements relative to one another. We therefore also collected methyl-methyl and methyl-amide 1H-1H NOEs using a [2H/15N/ILV-13Cmethyl]-labeled sample. The high quality of the 1H-13C HMQC spectrum of the methyl region (SI Appendix, Fig. S1) combined with long NOE mixing times (250 ms) on a 900-MHz spectrometer yields methyl-methyl NOE cross-peaks that can extend up to 10 Å (38, 39). Careful examination of the 3D 13C-separated NOE spectrum reveals strong long-range NOE cross-peaks between methyl groups of helices 1 to 3 that form the hydrophobic core of the JD domain (Fig. 3A, and SI Appendix, Fig. S2A) and between residues in successive β strands of the CTD domain (Fig. 3B). Methyl-methyl NOEs were also observed between strands β4 and β5 (Fig. 3A), a region in which interstrand HN-HN NOEs were absent, further suggesting that strand β5, although flexible, is stabilized by interactions with strand β4. Importantly, methyl-amide proton NOEs from the methyl groups of Val100 in helix 5 to the backbone amides of Glu55 and Val56 in helix 3 were identified (Fig. 3B), demonstrating that helix 5 forms a stable interaction with helix 3 of the JD domain.

Fig. 3.

Methyl NOE data and domain structures of DNAJB6b. Strips from a 900-MHz 3D NOE-HMQC spectrum (250 ms mixing time) showing (A) methyl-methyl and (B) methyl-amide NOEs. The data were collected on a 200-μM [2H/15N/ILV-13CH3]-labeled ΔST-DNAJB6b sample at 25 °C. (C) Superposition of the 10 lowest-energy CS-ROSETTA structures calculated for the JD (Top; helices 1 to 4 in red and helix 5 in purple) and CTD (Bottom; cyan) domains. The flexible linkers are not shown for clarity.

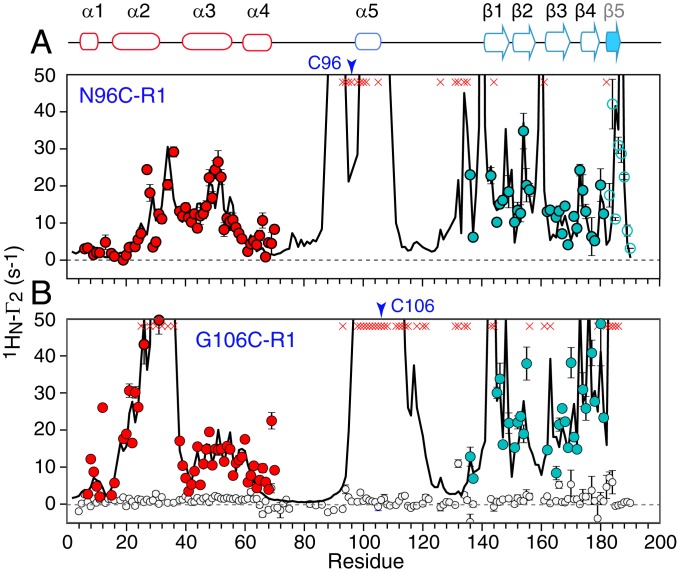

To further validate the interaction between helix 5 and the JD domain as well as to refine the position of helix 5 relative to the rest of the JD domain, paramagnetic relation enhancement (PRE) measurements were carried out. The magnitude of the PRE is proportional to the <r−6> paramagnetic label–proton distance, and the effect is large owing to the large magnetic moment of the unpaired electron. To this end, paramagnetic nitroxide spin labels (R1), one at a time, were introduced by conjugation of (1-oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-D3-pyrroline-3-methyl) methanethiosulfonate (MTSL) via disulfide linkages to 2 surface-engineered cysteines located at the N- (N96C-R1) and C- (G106-R1) terminal ends of helix 5 (Fig. 4). Strong 1HN PREs were observed from G106C-R1 to helix 2, with residues 25 to 36 completely broadened out, indicating that the C terminus of helix 5 is in close proximity to the middle of helix 2 (Fig. 4B). In addition, smaller PREs were observed from G106C-R1 to helix 3 (Fig. 4B). PRE data from N96C-R1 also showed PREs to helices 2 and 3 (Fig. 4A). These data are further supported by the observation that upon mutation of Val100 to Cys which disrupts helix 5, significant 1HN/15N chemical shift differences are observed for both helices 2 and 3 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B).

Fig. 4.

The 1HN-Γ2 PRE profiles recorded on nitroxide spin-labeled ΔST-DNAJB6b. PREs recorded on [2H/15N]-labeled ΔST-DNAJB6b with the nitroxide spin-label (R1) located at (A) N96C-R1 (60 μM) and (B) G106C-R1 (100 μM). PREs for the JD and CTD domains are shown in red and light blue, respectively. Data for the 2 flexible linkers are not shown for clarity. The 1H-15N cross-peaks that are broadened beyond detection are shown as red crosses. The black circles show a control experiment recorded on a sample of [2H/15N]-labeled ΔST-DNAJB6b in the presence of an equimolar concentration of the nitroxide free radical TEMPO (120 μM) each). No PREs are observed from TEMPO indicating that the interdomain PREs observed for N96C-R1 and G106-R1 are due to transient interdomain interaction and not from hydrophobic interactions between the nitroxide R1 label and the CTD domain. The solid lines are the calculated PREs obtained from Xplor-NIH PRE-driven simulated annealing calculations (see SI Appendix for full details) (36). The nitroxide spin labels are represented by 5-membered ensembles, and their positions and correlation times were optimized by simulated annealing to fit the intradomain PRE data from N96C-R1 and G106C-R1 to helices 1 to 4 of the JD domain. The calculated interdomain PRE data from N96C-R1 and G106-R1 to the CTD domain were obtained by ensemble PRE-driven simulated annealing in which the JD domain (including helix 5 and the nitroxide labels) were held fixed, the CTD domain was allowed to move as a rigid body, and linker 2 (residues 103 to 137) was given torsional degrees of freedom. The CTD and linker 2 were represented by an ensemble size of N = 6 (Fig. 6). The open blue circles for the PREs from N96C-R1 and involving strand β5 were not included in the simulated annealing calculations but back-calculated from the ensembles; the excellent agreement between observed and calculated values for these PREs serves to cross-validate the results.

The necessity for deuteration to overcome the increased linewidths of the CTD resonances together with the significant 1HN/15N cross-peak overlap for residues in the JD domain and the linkers does not lend itself to a conventional NOE-based structure determination. We therefore opted to use the chemical shift, RDC, and NOE, as well as the PRE data from the G106C-R1 variant to residues 25 to 36 of helix 2 (SI Appendix, Table S1), in conjunction with the program CS-ROSETTA (40, 41) to derive 3D models of the JD (residues 1 to 129) and CTD (residues 130 to 190) domains independently. The 10 lowest-energy structures for the 2 domains are displayed in Fig. 3C. In the case of the JD domain, the long flexible linker (residues 66 to 98) connecting helices α4 and α5 induces structural noise during fragment assembly impacting convergence, and therefore, an iterative CS-ROSETTA protocol was employed (41–43). The resulting models show a backbone root mean square deviation (rmsd) to the lowest-energy structure of 1.5 Å for the structured regions (SI Appendix, Fig. S3) and display good agreement with the RDC data (SI Appendix, Fig. S4) while satisfying all NOE distance restraints.

The JD domain adopts a fold that is very similar to that of homologous isolated JD domains (23, 24) with helices 2 and 3 antiparallel to one another and connected by a loop containing the DnaK binding HPD sequence motif (11–13) (Fig. 5A; note the face of the protein toward which the HPD side chains are pointing is referred to as the front side). A unique feature of the current structure is that helix 5 is packed against the front side of the JD domain, involving residues 26 to 30 of helix α2 and residues 47 to 52 of helix α3. Interestingly, the same residues are implicated in the interaction of the JD domain with the nucleotide binding domain of Hsp70 (12).

Fig. 5.

Structure of ΔST-DNAJB6b. Lowest-energy CS-ROSETTA structural model of the (A) JD and (B) CTD domains. In A, helix 5 is shown in purple, the nitroxide spin-label attachment positions are shown as blue spheres, the side chains of the HPD sequence motif are highlighted in green, and the backbone of residues previously identified to participate in the interface with Hsp70 (12) is indicated in orange. The side chains of the C-terminal 10 residues are shown in purple in B.

The CTD domain comprises a single, 4-stranded β sheet, with the strands reducing in size toward the C terminus (Fig. 5B), reminiscent of a single leaflet of a β propeller (44). The C-terminal 10 residues are predominantly disordered in 5 out the 10 lowest-energy models, while in the other 5 models, residues 181 to 185 form a short β5 strand (Fig. 3C). The extended conformation of the C-terminal residues is in marked contrast to the canonical DNAJB1 isoform where the C terminus forms a helix that acts as a dimerization domain (26).

Transient Interactions Between the JD and CTD Domains.

The large differences in the magnitude (Da) and rhombicity (η) of the alignment tensors for the JD and CTD domains of ΔST-DNAJB6b aligned in PEG/hexanol (Fig. 2F), together with the low heteronuclear 15N{1H} NOE values for the second linker (residues 106 to 133; Fig. 2A), are indicative of large-amplitude interdomain motion (37, 45). The single β-sheet CTD domain exposes numerous charged and hydrophobic side chains on both faces of the sheet that potentially could form intramolecular and intermolecular interactions. Large 1HN PREs are observed from both N96C-R1 and G106C-R1, located in helix 5, to residues in the CTD domain (Fig. 4 A and B). No significant PREs, however, are observed in the presence of the corresponding free radical, TEMPO (Fig. 5B), indicating that the PREs observed from N96C-R1 and G106C-R1 do not arise from nonspecific interactions attributable to the R1 spin label.

To obtain a more quantitative description of the transient interactions between the JD and CTD domains, we carried out a series of simulated annealing calculations driven by the PRE data using Xplor-NIH (36). Helices 1 to 4 of the JD domain and the CTD domain were treated as rigid bodies, while helix 5 was allowed to move (as a rigid body) within a range of 1.5 Å for the Cα atoms to reflect its Cα rmsd in the CS-ROSETTA calculations (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

The intradomain PREs from N96C-R1 and G106C-R1 in helix 5 to the rest of the JD domain fit well to the lowest-energy CS-ROSETTA model (Fig. 4 A and B, red circles), providing independent validation of the structure of the JD domain including helix 5 (Figs. 3C and 5A).

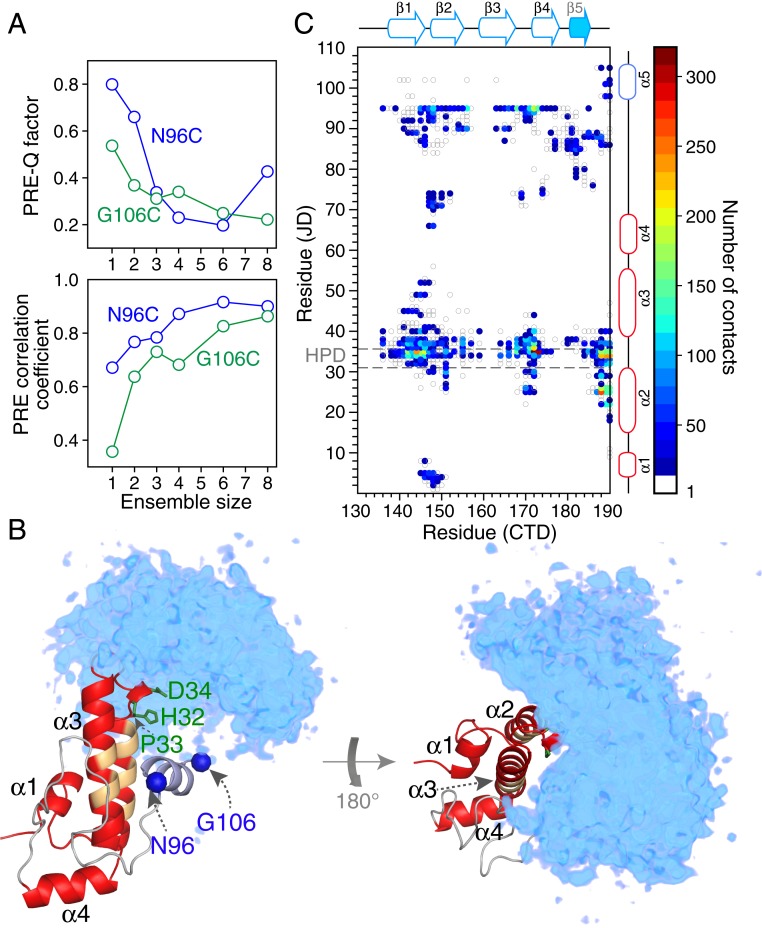

To fit the interdomain PRE data from N96C-R1 and G106C-R1 to the CTD domain (Fig. 4 A and B, cyan circles), the CTD domain was represented by an ensemble of varying size (N), ranging from 1 to 8 (46, 47). Since the population of the closed state giving rise to the interdomain PREs is unknown a priori, we made use of a PRE target function that maximizes the correlation coefficient between observed and calculated PREs (48). The PRE data were supplemented by highly ambiguous distance restraints (49) from all atoms of residues 34 and 36 in the JD domain, identified from 15N CPMG relaxation dispersion experiments (see following section) to be involved in interdomain contacts, to the atoms of all residues in the CTD domain. The PRE correlation coefficient increases as N increases, reaching a plateau of 0.8 to 0.9 for N ≥ 6 (Fig. 6A); likewise, the PRE Q factor decreases as N increases, reaching a minimum at N = 6 (Fig. 6B). One can therefore conclude that the closed form of ΔST-DNAJB6b is not a single well-defined state but rather an ensemble of transient, compact, interconverting species.

Fig. 6.

Analysis and visualization of the transient, sparsely populated closed state of ΔST-DNAJB6b from interdomain PRE data arising from nitroxide spin labels (R1) attached to surface engineered cysteine residues located at N96C and G106C. (A) Dependence of the Pearson correlation coefficient between observed and calculated PREs (Top) and PRE Q factor (Bottom); on ensemble size N. The agreement between observed and calculated PREs as a function of residue for the N = 6 ensemble calculations is displayed in Fig. 4. (B) Reweighted atomic probability density maps (50) of the CTD domain (cyan; shown at a contour level of 20%) with structures superimposed on the JD domain (red ribbon drawing), illustrating the conformational space sampled by the CTD domain relative to the JD domain. The nitroxide spin label attachment positions are shown as blue spheres, the side chains of the HPD motif are highlighted in green, and the backbone of residues previously identified to participate in the interface with Hsp70 (12) is indicated in orange. (C) Contact map showing transient interdomain contacts between the JD and CTD domains, calculated using the 10 lowest-energy ensembles (n = 6) and a cutoff of 8 Å. The HPD sequence motif is highlighted by the gray dashed lines. Details of the PRE-driven Xplor-NIH (36) simulated annealing calculations are provided in SI Appendix.

The closed state ensemble of ΔST-DNAJB6b is readily visualized from the reweighted atomic probability density map (50) shown in Fig. 6B and the interdomain contact map displayed in Fig. 6C. The CTD domain in the closed state ensemble interacts with the JD domain at the top of helices 2 and 3 in the front of the protein, with the HPD sequence motif (residues 32 to 34) located centrally at the interdomain interface (Figs. 4C and 6B). Several potential interdomain methyl-methyl NOEs could also be identified in the 3D 13C-separated NOE spectrum but due to ambiguities in their assignments were not used as restraints in the calculations. Further, cross-links between the JD and CTD domains have been detected for monomeric DNAJB6b by mass spectrometry (51) showing that these long-range interactions are also present in the full-length protein.

DNAJB6b Oligomerizes Through the CTD Domain.

The larger linewidths of 1HN/15N cross-peak resonances belonging to residues of the CTD domain in the context of both ΔST-DNAJB6b and especially full-length DNAJB6b (Fig. 1D) are indicative of exchange dynamics on the millisecond time scale. To probe these phenomena at atomic resolution we made use of an array of relaxation-based NMR methods including 15N lifetime line broadening (15N-ΔR2), Carr–Purcell–Mieboom–Gill (CPMG) relaxation dispersion, and exchange-induced shifts (52).

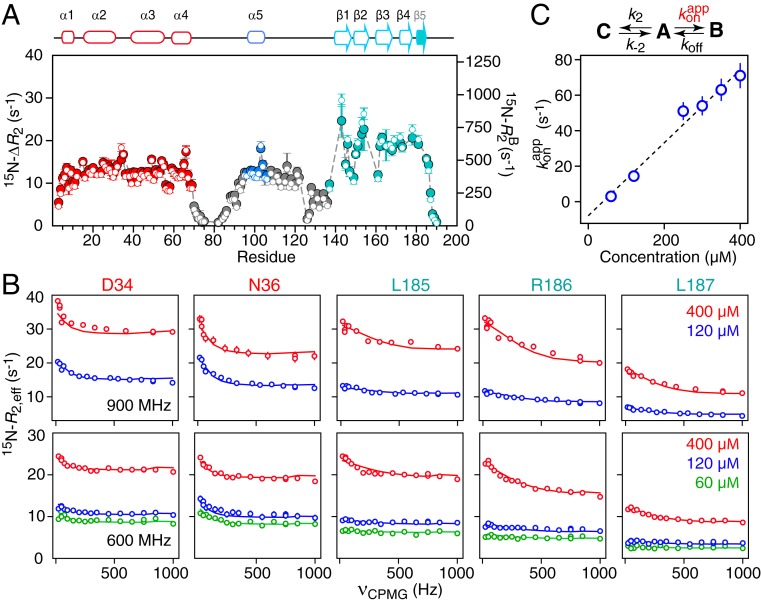

Fig. 7A shows the difference (ΔR2) in the 15N-R2 transverse relaxation rates between 60- and 400-μΜ samples of ΔST-DNAJB6b determined from 15N-R1ρ measurements in the presence of a strong 1.5-kHz spin lock to suppress chemical exchange line broadening. Substantial 15N-ΔR2 effects are observed for all residues with the exception of those in the flexible linkers (Fig. 7A). The ratio of 15N-ΔR2 values measured at spectrometer frequencies of 900 and 600 MHz is ∼1.3, as expected from 15N chemical shift anisotropy, and excludes any significant contribution from chemical exchange line broadening which increases as the square of the spectrometer frequency. While small 15N exchange induced shifts (15N-δex) up to 18 Hz are also observed between 60- and 400-μΜ samples (SI Appendix, Fig. S5), these do not correlate with the 15N-ΔR2 data, providing further evidence that chemical exchange line broadening is effectively suppressed by a 1.5-kHz spin lock field and that the ΔR2 effect arises from exchange between the observable monomeric species and NMR invisible high-molecular weight oligomers. The larger 15N-ΔR2 and δex values for residues in the CTD domain versus the JD domain (Fig. 7A and SI Appendix, Fig. S5) suggest that oligomerization is mediated via intermolecular interactions involving the CTD domain.

Fig. 7.

Quantitative analysis of 15N relaxation-based NMR data. (A) The 15N-ΔR2 profiles (filled in circles, y axis scale on the left) measured at 900 MHz as the difference in 15N-R2 rates between 400 and 60 μM samples of ΔST-DNAJB6b, together with the values of 15N- (open circles, y axis scale on the right) for the oligomer (state B) obtained from fitting all relaxation-based data (ΔR2, CPMG relaxation dispersion, and δex) to a branched 3-state model. The gray dashed lines are the calculated 15N-ΔR2 values obtained from the fit. (B) The 15N-CPMG relaxation dispersion profiles measured at 900 (Top) and 600 (Bottom) MHz at several different protein concentrations (as indicated in the figure). The experimental data are shown as open circles, and the best fits to the branching 3-state exchange model are shown as solid lines. (C) Linear concentration dependence of the pseudo–first-order association rate constant for the interconversion between the major open monomeric species (state A) and the oligomer-bound species (state B). (State C is the closed monomeric species.) The exchange-induced chemical shift data are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S5. All experimental data were recorded at 25 °C.

To investigate the underlying exchange processes in a quantitative manner, 15N CPMG relaxation dispersion data were collected on ΔST-DNAJB6b at several concentrations ranging from 60 to 400 μM (Fig. 7B). The C-terminal 5 residues (residues 185 to 190) display large Rex values (difference in R2,eff values at CPMG field strength of 0 and 1 kHz) at a concentration of 400 μM, which are greatly reduced when the concentration is decreased to 120 or 60 μM, indicative of an intermolecular exchange process. The Rex values for residues 34 and 36, located close to the HPD sequence motif, as well as for residues 165 and 175 in the CTD domain, on the other hand, are concentration independent, as expected for an intramolecular process arising from interdomain interactions between the JD and CTD domains.

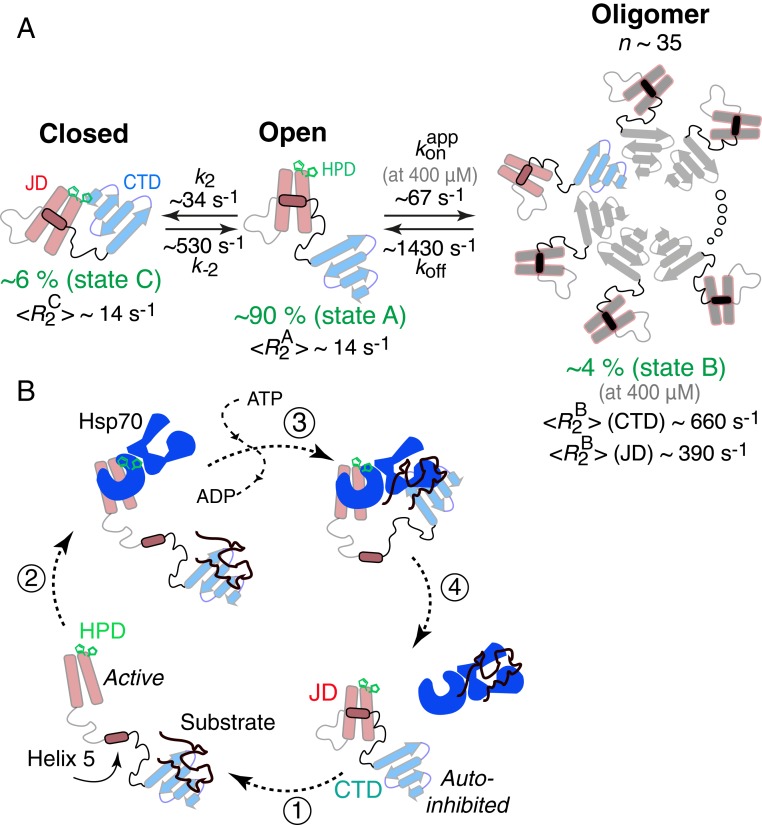

The 15N-CPMG relaxation dispersion, ΔR2, and δex data were fit simultaneously to a 3-state branching model (Figs. 7C and 8A). The major, NMR observable species (state A) is the open form of ΔST-DNAJB6b, which exchanges with 2 sparsely populated species: the ensemble of closed states (species C) via a concentration-independent unimolecular process and a large oligomeric state (species B) via a concentration-dependent process. The 15N-Δω values for residues 185 to 190 (concentration-dependent Rex) were assumed to be 0 for the A–C transition, while those for residues 34, 36, 165, and 175 (concentration-independent Rex) were assumed to be 0 for the A–B transition. In addition, the intrinsic transverse relaxation rates for the 2 monomeric species A and C were assumed to be equal. Because exchange between states A and B is fast on the relaxation time scale , the values of the population of state B (pB) and are partially correlated and cannot be resolved easily from the 15N CPMG relaxation dispersion and ΔR2 data alone; decorrelation of these 2 terms is achieved by incorporation of the exchange-induced shift (δex) data (53, 54) that effectively places an upper bound on the population pB of the oligomeric state (species B). Excellent fits to the data are obtained for the 3-state branching model as shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 8.

Kinetic scheme used to fit the 15N relaxation-based NMR data for ΔST-DNAJB6b and proposed mechanism of Hsp70 (DnaK) cycle regulation by Hsp40 (DnaJ). (A) The scheme involves a major open species (state A; pA ∼ 90%) in exchange with a closed monomeric species (state B; pB ∼ 6%), in which the HPD sequence motif plays an important role, and a large oligomeric state (state C; pC ∼ 4% at 400 μΜ). Based on the fitted 15N- values (at 25 °C) for the CTD domain, one can estimate that the oligomer is ∼850 kDa in molecular weight and consists of ∼35 monomeric units. (B) Proposed Hsp40 (DnaJ)–Hsp70 (DnaK) cycle. In the absence of a substrate, Hsp40 exists in an autoinhibited state where helix 5 (containing the DI/VF sequence motif) blocks the Hsp70 binding site. Upon substrate binding (step 1), a conformational change occurs that exposes the Hsp70 binding site allowing Hsp70 to bind via the HPD sequence motif (step 2). After ATP hydrolysis and substrate handover (step 3), the cycle is completed by the displacement of the Hsp70 ATPase domain by helix 5 of Hsp40 (step 4). Although DNAJB6b exists as an oligomer in vivo, we only show the monomer as this proposed mechanism is expected to be valid for other DnaJ proteins.

The overall exchange rate between open (A) and oligomeric (B) states is ∼1,500 s−1, while that between open (A) and closed (C) monomeric states is a factor of about 3 slower . At the highest concentration employed (400 μM) the population of the oligomeric state (B) is 4.2 ± 0.3%. The population of the closed monomeric species (C) is 5.7 ± 1.6%. The fitted values of exhibit a linear dependence upon concentration (Fig. 7C) indicating that the relaxation data report on an exchange phenomenon involving association/dissociation of the monomer with a stable oligomer rather than on the oligomerization process itself (in which case a higher-order dependence of on concentration would be observed).

The average value at 900 MHz and 25 °C is 660 ± 100 s−1 for the CTD domain, compared to values of 395 ± 65 and 385 ± 30 s−1 for the JD domain (helices 1 to 4) and helix 5, respectively (Fig. 7A). These data show that the CTD domain is immobilized upon interaction with the large oligomeric species and that the approximate size of the oligomer is close to 850 kDa, corresponding to ∼35 monomeric units. The 40% lower value for the JD domain and helix 5 indicate that helices 1 to 5 behave as a single unit in the oligomer-bound state and that they reorient semiindependently of the immobilized CTD, just as they do for the major species of the monomeric form. The loops between strands β1/β2 and β2/β3 in the CTD have systematically lower values (Fig. 7A) indicative of significant mobility in the oligomer-bound state and hence are presumably located on the face of the CTD that is not in direct contact with the large oligomeric species.

The 15N chemical shift differences (15N-Δω) for residues involved in interdomain interactions (34, 36, 165, and 175) are relatively small (∼0.5 ppm) as expected for transient rigid body docking of 2 domains with no changes in secondary or tertiary structure. The 15N-Δω values for the C-terminal residues (185 to 190), on the other hand, are significantly larger (1 to 2 ppm), suggesting that they may undergo some type of conformational change upon interaction with the oligomer species.

To validate these findings, we generated a truncation variant of DNAJB6b (DNAJB6b-ΔC10), in which only the last 10 C-terminal residues, including strand β5, were deleted, while the S/T loop was preserved (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). The CTD of ΔC10-DNAJB6b is severely exchange line-broadened, reflecting destabilization and possibly molten globule-like characteristics, as evidenced by the absence of all of the associated 1HN/15N cross-peaks from the 1H-15N TROSY HSQC spectrum (SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). The 1HN/15N cross-peaks belonging to residues in the JD domain, helix 5 and linker 1, however, remain largely unaffected and have essentially the same chemical shifts in the DNAJB6b-ΔC10, ΔST-DNAJB6b, and full-length DNAJB6b constructs (SI Appendix, Fig. S6B, and Fig. 1). As expected, the DNAJB6b-ΔC10 construct is also monomeric (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A) even though it contains the S/T loop previously thought to be the key driver for DNAJB6b oligomerization. Residues 34 and 36 of DNAJB6b-ΔC10 show flat 15N CPMG relaxation dispersion profiles (SI Appendix, Fig. S6C), confirming that the concentration-independent profiles observed in the presence of a well-folded CTD (as in the ΔST-DNAJB6b construct; Fig. 7B) arise from transient interdomain interactions (Fig. 4). Taken together, these data reveal an intricate balance between interdomain (intramolecular) and intermolecular interactions that determine the oligomerization state of DNAJB6b and can modulate Hsp70 and/or substrate binding.

Concluding Remarks.

Despite considerable scientific interest in J-domain proteins as modulators of the Hsp70 machine (6, 9), the mechanism by which they regulate proteostasis is not understood in detail. However, the wealth of biochemical and cellular data often cannot be rationalized by current structural understanding of the system, largely because the available structural information is limited to truncated constructs. For example, the current (structural) view of the Hsp40–Hsp70 interaction is concerned with the interaction between the JD domain of Hsp40 and the ATPase domain of Hsp70 and the consequent increase in ATP hydrolysis. However, the G/F linker that connects the 2 domains has been known to confer much of the specificity and regulation of the interaction (14–16) in a completely unknown manner. Here we show that 10 out of 62 otherwise highly flexible linker residues in ΔST-DNAJB6b (and 117 residues in DNAJB6b) form a stable helix (helix 5), containing the DI/VF sequence motif, that interacts with helices 2 and 3 of the JD domain (Fig. 5A) to create an autoinhibited form of the protein. The binding surface for helix 5 on helices 2 and 3 (Fig. 5A) overlaps with that for DnaK binding, as shown by the recent crystal structure of DNAJB1 fused to DnaK (12). These observations immediately suggest that helix 5 competes with DnaK for binding to the JD domain (Fig. 8B). Indeed, the DI/VF sequence motif is critical for cell growth under stress (14, 15), while mutations that destabilize that part of the protein lead to Hsp70-dependent cell death. In the absence of a stable helix 5, the Hsp70 binding site is always exposed leading to Hsp70 sequestration with deleterious effects for the cell (14, 15) (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Mutations in the HPD sequence motif (located at the top of helix 2) can reverse that effect by inhibiting Hsp70 binding to an otherwise exposed interface (14, 15) (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Further, we show that the HPD sequence motif, in addition to being crucial for Hsp70 binding, plays an important role in interdomain interactions (Fig. 4) that may modulate recruitment of Hsp70 and substrate recognition. Taking into account the high sequence conservation of the DI/VF sequence motif (helix 5) across all members of the DnaJ family, these findings can potentially be generalized to all J proteins. Indeed, in the original NMR structure of a JD domain from Escherichia coli, the DI/VF sequence motif exhibited reduced dynamics (23), although complete formation of helix 5 was not observed, potentially because the construct used was truncated immediately after the C terminus of the helix, altering its stability.

In addition to recruiting Hsp70, DNAJB6b can act as a substoichiometric inhibitor of aggregating proteins in the absence of Hsp70 (20). The structure of the CTD domain provides clues of a potential mechanism. Fig. 7 shows that the CTD domain self-associates via β-strand/β-strand interactions, which is also supported by intermolecular cross-links observed for DNAJB6b (51). Although the equilibrium is shifted to the monomer in the ΔST-DNAJB6b construct in which the S/T loop is truncated, full-length DNAJB6b is oligomeric. The subunits in these β-strand–rich oligomers are in dynamic exchange (Fig. 1 and ref. 27) and can potentially incorporate β sheets from one or more polypeptide chains undergoing a transition to a cross-β structure. In this scenario the rate of primary nucleation would be dramatically reduced (20), explaining the substoichiometric activity of the protein. The role of the S/T loop in substrate recognition and/or subunit dynamics remains to be elucidated (21).

In conclusion, the structure of DNAJB6b presented here suggests that the DI/VF sequence motif acts as a crucial switch that determines the state of the entire Hsp40–Hsp70 machine and eventually chaperone activity and cell death or survival. Further, our results elucidate the mechanism of oligomerization of DNAJB6b and potentially the means of inhibition of aggregation. A better understanding of substrate specificity and dynamic regulation of the Hsp40 system opens the way for targeted intervention at the substrate delivery stage without affecting the vital Hsp70 machinery.

Experiment

Details of protein expression and purification, isotope-labeling, site-specific nitroxide spin-labeling (R1), sample conditions, NMR experimental details, quantitative analysis of NMR-based relaxation data (15N-CPMG relaxation dispersion, ΔR2, and exchange-induced shifts), and structural modeling including CS-ROSETTA and Xplor-NIH calculations are provided in SI Appendix. All experiments were performed at 25 °C.

Atomic coordinates of ΔST-DNAJB6b, as well as experimental restraints, have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.wwpdb.org [PDB ID codes 6U3R (55) and 6U3S (56)], and backbone assignments for the ΔST-DNAJB6b variant have been deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank, www.bmrb.wisc.edu [BMRB ID code 30656 (57)].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Charles Schwieters and Harm Kampinga for useful discussions; and Drs. James Baber, Dan Garrett, and Jinfa Ying for technical support. This work was funded by the Intramural Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health (to G.M.C.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

Data deposition: The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank www.wwpdb.org (PDB ID codes 6U3R and 6U3S [coordinates and restraints]) and Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank www.bmrb.wisc.edu (BMRB ID code 30656 [chemical shifts]).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1914999116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Chiti F., Dobson C. M., Protein misfolding, amyloid formation, and human disease: A summary of progress over the last decade. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 86, 27–68 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benilova I., Karran E., De Strooper B., The toxic Aβ oligomer and Alzheimer’s disease: An emperor in need of clothes. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 349–357 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fusco G., et al. , Structural basis of membrane disruption and cellular toxicity by α-synuclein oligomers. Science 358, 1440–1443 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laganowsky A., et al. , Atomic view of a toxic amyloid small oligomer. Science 335, 1228–1231 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ono K., Condron M. M., Teplow D. B., Structure-neurotoxicity relationships of amyloid beta-protein oligomers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 14745–14750 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim Y. E., Hipp M. S., Bracher A., Hayer-Hartl M., Hartl F. U., Molecular chaperone functions in protein folding and proteostasis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 82, 323–355 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muchowski P. J., Wacker J. L., Modulation of neurodegeneration by molecular chaperones. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 11–22 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wentink A., Nussbaum-Krammer C., Bukau B., Modulation of amyloid states by molecular chaperones. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 11, a033969 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kampinga H. H., Craig E. A., The Hsp70 chaperone machinery: J proteins as drivers of functional specificity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 579–592 (2010). Erratum in: Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.11, 750 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayer M. P., Bukau B., Hsp70 chaperones: Cellular functions and molecular mechanism. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62, 670–684 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greene M. K., Maskos K., Landry S. J., Role of the J-domain in the cooperation of Hsp40 with Hsp70. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 6108–6113 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kityk R., Kopp J., Mayer M. P., Molecular mechanism of J-domain-triggered ATP hydrolysis by Hsp70 chaperones. Mol. Cell 69, 227–237.e4 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suh W.-C., et al. , Interaction of the Hsp70 molecular chaperone, DnaK, with its cochaperone DnaJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 15223–15228 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cajo G. C., et al. , The role of the DIF motif of the DnaJ (Hsp40) co-chaperone in the regulation of the DnaK (Hsp70) chaperone cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 12436–12444 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wall D., Zylicz M., Georgopoulos C., The conserved G/F motif of the DnaJ chaperone is necessary for the activation of the substrate binding properties of the DnaK chaperone. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 2139–2144 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan W., Craig E. A., The glycine-phenylalanine-rich region determines the specificity of the yeast Hsp40 Sis1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 7751–7758 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiu X. B., Shao Y. M., Miao S., Wang L., The diversity of the DnaJ/Hsp40 family, the crucial partners for Hsp70 chaperones. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 63, 2560–2570 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu Y., Li J., Jin Z., Fu Z., Sha B., The crystal structure of the C-terminal fragment of yeast Hsp40 Ydj1 reveals novel dimerization motif for Hsp40. J. Mol. Biol. 346, 1005–1011 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hageman J., et al. , A DNAJB chaperone subfamily with HDAC-dependent activities suppresses toxic protein aggregation. Mol. Cell 37, 355–369 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Månsson C., et al. , Interaction of the molecular chaperone DNAJB6 with growing amyloid-beta 42 (Aβ42) aggregates leads to sub-stoichiometric inhibition of amyloid formation. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 31066–31076 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Månsson C., et al. , Conserved S/T-residues of the human chaperone DNAJB6 are required for effective inhibition of Aβ42 amyloid fibril formation. Biochemistry 57, 4891–4902 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitra A., et al. , Large isoform of MRJ (DNAJB6) reduces malignant activity of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 10, R22 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pellecchia M., Szyperski T., Wall D., Georgopoulos C., Wüthrich K., NMR structure of the J-domain and the Gly/Phe-rich region of the Escherichia coli DnaJ chaperone. J. Mol. Biol. 260, 236–250 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qian Y. Q., Patel D., Hartl F. U., McColl D. J., Nuclear magnetic resonance solution structure of the human Hsp40 (HDJ-1) J-domain. J. Mol. Biol. 260, 224–235 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kakkar V., et al. , The S/T-Rich motif in the DNAJB6 chaperone delays polyglutamine aggregation and the onset of disease in a mouse model. Mol. Cell 62, 272–283 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu J., et al. , The crystal structure of the putative peptide-binding fragment from the human Hsp40 protein Hdj1. BMC Struct. Biol. 8, 3 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Månsson C., et al. , DNAJB6 is a peptide-binding chaperone which can suppress amyloid fibrillation of polyglutamine peptides at substoichiometric molar ratios. Cell Stress Chaperones 19, 227–239 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bax A., Grzesiek S., Methodological advances in protein NMR. Acc. Chem. Res. 26, 131–138 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen Y., Bax A., Protein backbone and sidechain torsion angles predicted from NMR chemical shifts using artificial neural networks. J. Biomol. NMR 56, 227–241 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bax A., Grishaev A., Weak alignment NMR: A hawk-eyed view of biomolecular structure. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 15, 563–570 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clore G. M., Starich M. R., Gronenborn A. M., Measurement of residual dipolar couplings of macromolecules aligned in the nematic phase of a colloidal suspension of rod-shaped viruses. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 10571–10572 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rückert M., Otting G., Alignment of biological macromolecules in novel nonionic liquid crystalline media for NMR experiments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 7793–7797 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mesleh M. F., Veglia G., DeSilva T. M., Marassi F. M., Opella S. J., Dipolar waves as NMR maps of protein structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 4206–4207 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clore G. M., Gronenborn A. M., Bax A., A robust method for determining the magnitude of the fully asymmetric alignment tensor of oriented macromolecules in the absence of structural information. J. Magn. Reson. 133, 216–221 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Warren J. J., Moore P. B., A maximum likelihood method for determining D(a)(PQ) and R for sets of dipolar coupling data. J. Magn. Reson. 149, 271–275 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwieters C. D., Bermejo G. A., Clore G. M., Xplor-NIH for molecular structure determination from NMR and other data sources. Protein Sci. 27, 26–40 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Braddock D. T., Cai M., Baber J. L., Huang Y., Clore G. M., Rapid identification of medium- to large-scale interdomain motion in modular proteins using dipolar couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 8634–8635 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sounier R., Blanchard L., Wu Z., Boisbouvier J., High-accuracy distance measurement between remote methyls in specifically protonated proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 472–473 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Godoy-Ruiz R., Guo C., Tugarinov V., Alanine methyl groups as NMR probes of molecular structure and dynamics in high-molecular-weight proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 18340–18350 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen Y., et al. , Consistent blind protein structure generation from NMR chemical shift data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 4685–4690 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raman S., et al. , NMR structure determination for larger proteins using backbone-only data. Science 327, 1014–1018 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lange O. F., Baker D., Resolution-adapted recombination of structural features significantly improves sampling in restraint-guided structure calculation. Proteins 80, 884–895 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sgourakis N. G., et al. , The structure of mouse cytomegalovirus m04 protein obtained from sparse NMR data reveals a conserved fold of the m02-m06 viral immune modulator family. Structure 22, 1263–1273 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pons T., Gómez R., Chinea G., Valencia A., Beta-propellers: Associated functions and their role in human diseases. Curr. Med. Chem. 10, 505–524 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deshmukh L., et al. , Structure and dynamics of full-length HIV-1 capsid protein in solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 16133–16147 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clore G. M., Iwahara J., Theory, practice, and applications of paramagnetic relaxation enhancement for the characterization of transient low-population states of biological macromolecules and their complexes. Chem. Rev. 109, 4108–4139 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iwahara J., Schwieters C. D., Clore G. M., Ensemble approach for NMR structure refinement against (1)H paramagnetic relaxation enhancement data arising from a flexible paramagnetic group attached to a macromolecule. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 5879–5896 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kotler S. A., et al. , Probing initial transient oligomerization events facilitating Huntingtin fibril nucleation at atomic resolution by relaxation-based NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 3562–3571 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clore G. M., Schwieters C. D., Docking of protein-protein complexes on the basis of highly ambiguous intermolecular distance restraints derived from 1H/15N chemical shift mapping and backbone 15N-1H residual dipolar couplings using conjoined rigid body/torsion angle dynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 2902–2912 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwieters C. D., Clore G. M., Reweighted atomic densities to represent ensembles of NMR structures. J. Biomol. NMR 23, 221–225 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Söderberg C. A. G., et al. , Structural modelling of the DNAJB6 oligomeric chaperone shows a peptide-binding cleft lined with conserved S/T-residues at the dimer interface. Sci. Rep. 8, 5199 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anthis N. J., Clore G. M., Visualizing transient dark states by NMR spectroscopy. Q. Rev. Biophys. 48, 35–116 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Libich D. S., Fawzi N. L., Ying J., Clore G. M., Probing the transient dark state of substrate binding to GroEL by relaxation-based solution NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 11361–11366 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tugarinov V., Clore G. M., Exchange saturation transfer and associated NMR techniques for studies of protein interactions involving high-molecular-weight systems. J. Biomol. NMR 10.1007/s10858-019-00244-6 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karamanos T. K., Tugarinov V., Clore G. M., Solution NMR structure of the DNAJB6b deltaST variant (aligned on the J domain). Protein Data Bank. https://www.rcsb.org/structure/6U3R. Deposited 22 August 2019.

- 56.Karamanos T. K., Tugarinov V., Clore G. M., Solution NMR structure of the DNAJB6b deltaST variant (aligned on the CTD domain). Protein Data Bank. https://www.rcsb.org/structure/6U3S. Deposited 22 August 2019.

- 57.Karamanos T. K., Tugarinov V., Clore G. M., Solution NMR structure of the DNAJB6b deltaST variant (aligned on the J/CTDdomain. Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank. http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu/data_library/summary/index.php?bmrbId=30656. Deposited 22 August 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.