Abstract

Food insecurity, or the limited access to food, has been associated with maternal child feeding styles and practices. While studies in other parenting domains suggest differential and additive impacts of poverty-associated stressors during pregnancy and infancy, few studies have assessed relations between food insecurity during these sensitive times and maternal infant feeding styles and practices. This study sought to analyze these relations in low-income Hispanic mother-infant pairs enrolled in a randomized controlled trial of an early obesity prevention program (Starting Early). Food insecurity was measured prenatally and during infancy at 10 months. Food insecurity timing was categorized as never, prenatal only, infancy only, or both. Regression analyses were used to determine relations between food insecurity timing and styles and practices at 10 months, using never experiencing food insecurity as the reference, adjusting for family characteristics and material hardships. 412 mother-infant pairs completed 10-month assessments. Prolonged food insecurity during both periods was associated with greater pressuring, indulgent and laissez-faire styles compared to never experiencing food insecurity. Prenatal food insecurity was associated with less vegetable and more juice intake. If food insecurity is identified during pregnancy, interventions to prevent food insecurity from persisting into infancy may mitigate the development of obesity-promoting feeding styles and practices.

Keywords: Food insecurity, Pregnancy, Infancy, Feeding styles, Hispanic

INTRODUCTION

Food insecurity, defined as a household’s inconsistent access to adequate and nutritious food, (Anderson, 1990) is common during pregnancy and infancy in families living in poverty. Reasons for this include significant financial burdens that result from higher nutritional needs, shifts in household responsibilities and employment changes (Braveman et al., 2010; Ivers et al., 2011; Laraia et al., 2006). Household food insecurity during these periods results in adverse impacts on child health outcomes (Shonkoff et al., 2012) in both low and high income countries, including child obesity (Alaimo et al., 2001; Casey et al., 2001; Casey et al., 2006; Cook et al., 2004; Dubois et al., 2006; Metallinos-Katsaras et al., 2009; Suglia et al., 2013; Farrell et al., 2017). Studies of food insecurity in households with older children found that food insecure households consumed more low-cost, high-energy-dense foods (Drewnowski et al., 2004), had fewer cooking supplies (Matheson et al., 2002), and focused on the amount of food rather than the quality (Matheson et al., 2006), compared to food secure households. However, the mechanisms linking food insecurity during pregnancy and infancy to child obesity remain unclear.

Maternal infant feeding styles and practices may represent a potential mechanism linking household food insecurity to childhood obesity. Maternal infant feeding styles are defined as a mother’s beliefs and practices related to regulating infant feeding. Feeding styles are a potential mechanism through which household food insecurity during pregnancy and infancy could affect child diet and growth (Bronte-Tinkew et al., 2007; Gross et al, 2012; Gross et al., 2016a; Laraia et al., 2006; Laraia et al., 2015). Studies suggest that obesity-promoting non-responsive maternal infant feeding styles (DiSantis et al., 2011; Hurley et al., 2011), in which mothers regulate feeding without responding appropriately to infant hunger and satiety cues, are associated with household food insecurity (Feinberg et al., 2008; Gross et al., 2012). Connecting food insecurity with non-responsive feeding styles is important because these styles have been linked to child obesity in two ways: 1) documented associations with obesogenic practices, such as decreased exclusive breastfeeding (Taveras et al., 2004), lower consumption of fruits and vegetables (Patrick et al., 2005; O’Connor et al., 2010; Blissett et al., 2011) and higher intake of sugary drinks (Hennessy et al., 2012); and 2) potential disruption of infant self-regulatory capacity, leading to eating in the absence of hunger and continued feeding beyond fullness, and ultimately increased caloric intake (Costanzo et al., 1985; Birch et al., 1995; 2001; Hurley et al., 2011; Disantis et al., 2011). However, the evidence linking food insecurity to feeding styles has been limited by the assessment of food insecurity at only a single time point (Bronte-Tinkew et al., 2007; Gross et al, 2012; Gross et al., 2016a; Laraia et al., 2006; Laraia et al., 2015). This is an important limitation because food insecurity is known to fluctuate over time and it is likely that vulnerability may differ depending on the timing and duration of exposure (Nord et al., 2007). Furthermore, pregnancy and infancy are known to be sensitive periods of vulnerability to stress more generally. Determining whether infants are more vulnerable to the impact of food insecurity if it occurs during both pregnancy and infancy would aid in targeting preventive efforts.

Studies of other poverty-associated stressors, in particular maternal depression, demonstrate both differential and additive effects during the prenatal and infancy periods. Studies comparing mothers with only prenatal depression to mothers with only post-natal depression found differential effects, with post-natal depression resulting in increased child anti-social behaviors (Kim-Cohen et al., 2005), insecure attachments and behavioral problems (Murray, 1992). Depression occurring during both pregnancy and infancy has additive impacts on negative child developmental outcomes (Monk et al., 2012). No studies to our knowledge have longitudinally assessed the differential and additive impacts of household food insecurity during the prenatal and infancy periods on maternal infant feeding styles and practices during infancy. Therefore, we sought to address these gaps by determining the differential and additive impacts of household food insecurity during both the prenatal and infancy periods on obesity-promoting maternal infant feeding styles and practices at infant age 10 months. We hypothesized that food insecurity during pregnancy and infancy would be associated with decreased responsive maternal infant feeding styles and increased non-responsive maternal infant feeding styles, specifically controlling, indulgent and laissez-faire styles. We also hypothesized that food insecurity would be related to obesity-promoting infant feeding practices such as decreased breastfeeding and fruit and vegetables consumption and increased juice consumption.

METHODS

Study Design

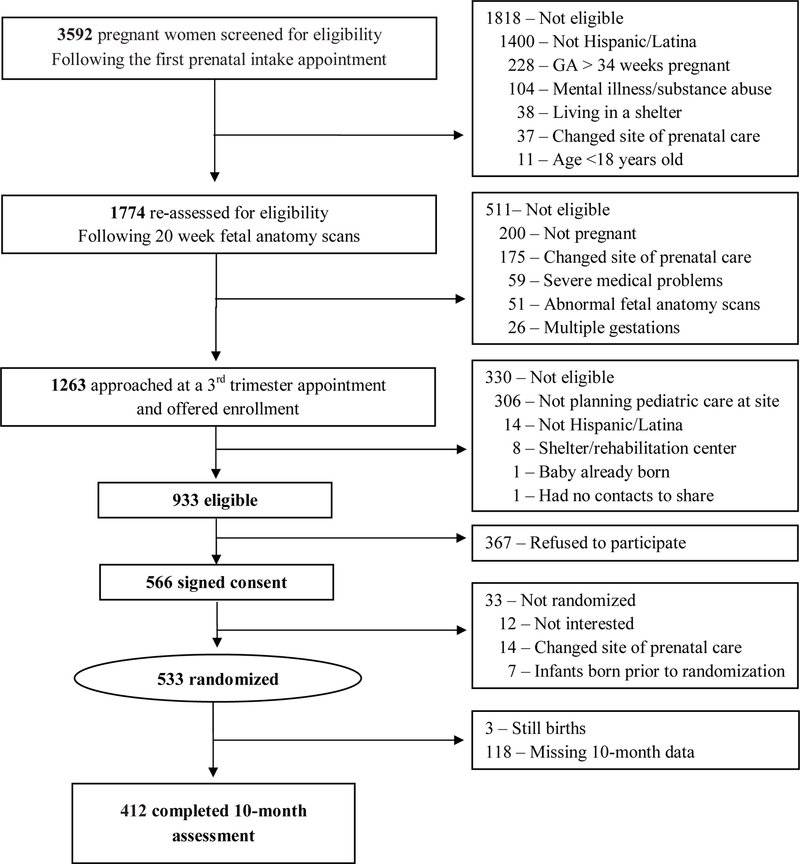

We performed a secondary longitudinal analysis of data from the Starting Early Study, an ongoing randomized controlled trial whose primary outcomes are to improve growth trajectories and reduce child obesity in the first three years of life. (Gross et al., 2016b) The Starting Early Study, designed for low-income Hispanic families, began in the third trimester of pregnancy and continued until child age 3 years old. Upon enrollment, participants were informed that the purpose of the program was to help develop healthy infant feeding and activity habits and promote healthy infant growth. Study enrollment and prenatal baseline assessments occurred between August 2012 and December 2014 (Figure 1). A subsequent follow-up assessment occurred at infant age 10 months. Women (n=533) were randomly allocated to a standard care control group or an intervention group participating in prenatal and postpartum individual nutrition/breastfeeding counseling and subsequent nutrition and parenting support groups coordinated with well-child visits. This study was approved by the institutional review boards of New York University School of Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bellevue Hospital Center, and the New York City Health and Hospitals. This study was registered on clinicaltrials.gov ().

Figure 1:

Participant enrollment and assessment

Study Sample

This study took place in the prenatal and pediatric clinics of a large urban public hospital and an affiliated satellite neighborhood health center. We included women who: 1) were at least 18 years old, 2) Hispanic/Latina, 3) English or Spanish speaking, 4) had a singleton uncomplicated pregnancy, and 5) had the intention to receive well child care at the study sites. We excluded those with significant medical or psychiatric illness, homelessness, substance abuse or severe fetal anomalies. Women were assessed for eligibility at a prenatal visit between 28 and 32 weeks gestational age (Gross et al., 2016b). Interested participants signed written informed consent. All participants who completed prenatal baseline assessments and the follow-up assessment at infant age 10 months were included in these analyses (n=412). Mothers who did not complete the 10-month assessment were similar to those who did, except they were younger (26.3 years vs. 28.1 years, p<.003) and more likely first-time mothers (51.2% vs. 33.3%, p<0.001). There were no significant differences in the prevalence of food insecurity or other material hardships.

Assessments

Trained research assistants conducted surveys in English or Spanish in person at baseline during a prenatal visit and by telephone for the follow-up assessment at infant age 10 months. Assessments were obtained to determine the relations between food insecurity timing (Bickel et al., 2000) and maternal infant feeding style subscale scores (Thompson et al., 2009) and maternal infant feeding practices (Fein et al., 2008). Adjusted analyses controlled for family characteristics and other material hardships (U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census., 1997; Shulman et al., 2006). Accounting for multiple other aspects of socioeconomic hardship would help distinguish the unique effects of food insecurity.

Independent Variables

Household food insecurity was assessed using the Core Food Security Module from the United States Department of Agriculture (alpha=.86 to .93) (Bickel et al., 2000; Carlson et al., 1999). The survey assessed food insecurity during the prior 12-month period. Food insecurity was first assessed at baseline during a third trimester prenatal visit, reflecting a period that overlapped with the pregnancy. Food insecurity was assessed again during the follow-up assessment at infant age 10 months. Continuous scores were generated from 10 questions at each time point and dichotomized using suggested cut points. Women were classified as food secure if they reported 2 or less food insecure conditions and food insecure if they reported 3 or more. Food insecurity timing was categorized as never (no food insecurity during pregnancy or infancy), prenatal only (food insecure during pregnancy but not during infancy), infancy only (food insecure during infancy but not during pregnancy), or both (food insecure during both pregnancy and infancy).

Dependent Variables

Maternal-infant feeding styles at infant age 10 months were assessed using the Infant Feeding Style Questionnaire (IFSQ), an instrument validated in a Hispanic sample (Thompson et al., 2009; Wood et al., 2016). It assessed five feeding style domains: (1) responsive, in which the mother is attentive to infant feeding cues while appropriately monitoring the quality and quantity of the infant’s diet; (2) pressuring/controlling, in which the mother encourages intake even if the infant is not hungry (3) restrictive/controlling, in which the mother excessively limits food even when the infant is still hungry; (4) indulgent, in which the mother is sensitive to cues but does not set limits on the food; and (5) laissez-faire, in which the mother does not limit infant diet and shows little interaction with the infant during feeding. These five broader feeding style domains have been further subdivided into 13 subscales (Table 1): 1) responsive included two subscales: attention (alpha=.84) and satiety (α=.92); 2) pressuring/controlling included three subscales: pressuring to finish (α=.79), pressuring with cereal (α=.78) and pressuring to soothe (α=.84); 3) restrictive/controlling included two subscales: amount consumed (α=.75) and diet quality (α=.85); 4) indulgent included four subscales: permissive (α=.82), coaxing (α=.89), soothing (α=.87) and pampering (α=.94); and 5) laissez-faire included two subscales: attention (α=.80) and diet quality (α=.91). These scales range from mean scores of 1 to 5, with higher scores being more representative of the given construct.

Table 1:

Infant Feeding Style Questionnaire sub-scales and sample questionsa

| Feeding Style Sub-Scales | Number of Items | Sample Question | Mean (SD)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Responsive – attention | 5 | I talk to my child to encourage him or her to eat. | 3.95 (.86) |

| Responsive – satiety | 5 | I pay attention when my child seems to be telling me that s/he is full or hungry. | 4.46 (.49) |

| Pressuring to finish | 8 | If my child seems full, I encourage him/her to finish his/her food anyway. | 2.65 (.86) |

| Pressuring with cereal | 5 | I gave my child cereal in the bottle. | 2.13 (.96) |

| Pressuring – soothing | 4 | When my child cries, I immediately feed him/her. | 2.57 (1.18) |

| Restrictive – amount consumed | 4 | I am very careful not to feed my child too much. | 3.90 (1.05) |

| Restrictive – diet quality | 7 | I let my baby eat junk food like potato chips, Doritos and cheese puffs.c | 4.19 (.66) |

| Indulgent – permissive | 8 | I allow child to eat fast food if he or she wants to. | 1.39 (.47) |

| Indulgent – coaxing | 8 | I allow child to eat fast food to make sure he or she gets enough. | 1.15 (.32) |

| Indulgent – soothing | 8 | I allow child to eat fast food to keep him/her from crying. | 1.15 (.32) |

| Indulgent – pampering | 8 | I allow child to eat fast food to keep him/her happy. | 1.16 (.33) |

| Laissez-faire – attention | 5 | I watch TV while feeding my child. | 1.57 (.64) |

| Laissez-faire – diet quality | 6 | I make sure my child does not eat sugary food like candy, ice cream, cakes or cookies.c |

1.73 (.63) |

Thompson, A. L., Mendez, M. A., Borja, J. B., Adair, L. S., Zimmer, C. R., & Bentley, M. E. (2009). Development and validation of the infant feeding style questionnaire. Appetite, 53(2), 210–221.

Mean scores for each subscale are based on scores ranging from 1 to 5.

Sample question is inversely related to feeding style.

Maternal-infant feeding practices were assessed using questions adapted from the Infant Feeding Practices Study II, a national longitudinal study of infant feeding (Fein et al., 2008). Breastfeeding was assessed by asking: “What kind of milk is your baby drinking now?” Breast milk as the only milk source was defined as breast milk only vs. any other milk or combination of milk. The number of times the infant ate fruit and vegetables and a family meal together in the last 7 days was assessed. These practices were dichotomized as 7 or more vs. less than 7 to estimate daily behaviors. Juice intake and self-feeding defined as whether the infant uses his/her fingers to feed him/herself was also assessed.

Covariates

Family characteristics and other material hardships were assessed at baseline during the third trimester of pregnancy. Family characteristics assessed included education, marital status, employment, country of birth, and having other children. Prenatal depressive symptoms was measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (Kroenke et al., 2001), a validated tool used to measure symptoms in the prior 2 weeks (α=.89). Depressive symptoms (scale of 0–27) were dichotomized at recommended cut points with no symptoms (0–4) versus mild or greater symptoms (5–27). Pre-pregnancy body mass index (calculated as weight [kg]/height [m2]) was calculated using weight and height from medical record review and categorized as underweight (<18.5), normal weight (18.5–24.9), overweight (25–29.9), and obese (>30) (Kuczmarski et al., 1997).

Other material hardships that were assessed included difficulty paying bills, housing disrepair and neighborhood stress. Difficulties paying bills was assessed using two questions from the Survey of Income and Program Participation about the ability to pay monthly bills including rent or mortgage, and times when the household had service turned off by the gas, electric or telephone company in the past 12 months (U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census., 1997). Continuous scores were generated based on the sum of the responses from the two questions. A categorical variable was created and defined as responding positively to either questions. Housing disrepair was also measured using questions from the Survey of Income and Program Participation (U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census., 1997). We assessed whether households experienced: 1) a leaking roof or ceiling, 2) broken toilet, hot water heater or other plumbing, 3) broken windows, 4) exposed wires, 5) rats, mice, roaches or other insects, 6) holes in floor, and 7) open cracks or holes in the walls or ceiling. Continuous scores were generated based on the number of housing conditions experienced. A categorical variable for housing disrepair was created and defined as responding positively to any of the listed housing conditions. Neighborhood stress was measured using questions from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System Centers for Disease Control and Prevention model surveillance protocol (Shulman et al., 2006). Mothers were asked whether because they felt unsafe to leave or return to their neighborhood: 1) they missed doctor or other appointments; 2) they limited grocery or other shopping; and 3) they stayed with other family members or friends. Responses were based on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from never, almost never, sometimes, fairly often and always. Continuous scores were generated from the sum of the three questions. A categorical variable was defined as never versus ever experiencing neighborhood stress.

Statistical Analysis

Data analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software version 18.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Il). First, we described family characteristics and other material hardships based on food security timing using chi-square analyses. We performed bivariate analyses of the associations between food insecurity timing and maternal infant feeding style subscale scores at infant age 10 months using one-way analysis of variance and Cohen’s d was calculated. To investigate differential and additive effects of household food insecurity timing on maternal infant feeding styles, we performed separate multiple linear regression models to predict each individual feeding style subscale, using “never” as the reference group. The distribution of five feeding style subscales were skewed: laissez-faire attention (skewness [standard error] = 1.37 [.12]); indulgent permissive (1.54 [.12]); indulgent coaxing (3.67 [.12]); indulgent soothing (3.38 [.12]) and indulgent pampering (3.15 [.12]). Multiple linear regression analyses for these five subscales were performed using log-transformation to account for skewing. Given that all significant and non-significant variables remained the same, associations for non-transformed feeding scales were reported to facilitate the interpretability of the effect sizes. Due to concern of heteroscedascity, a sensitivity analysis was undertaken using logistic regression with dichotomous feeding style subscales dichotomized at the top tertile, and found no differences in statistical inferences. Multicollinearity was not significant when examined using variance inflation factors and correlation matrices. Model 1 determined unadjusted relations between food insecurity timing and each individual feeding style subscale. Model 2 adjusted for family characteristics, including education, marital status, employment, country of birth, having other children, prenatal depressive symptoms, and pre-pregnancy weight status. Model 2 also adjusted for intervention group status. Model 3 further adjusted for other material hardships to determine the independent association of food insecurity above other poverty-associated risks. We added an interaction term, which multiplies together the dichotomous variables for prenatal depressive symptoms and food insecurity timing to determine if depressive symptoms moderated the relations between food insecurity timing and feeding styles. To investigate differential and additive effects of household food insecurity timing on maternal infant feeding practices, we performed separate logistic regression models to predict each feeding practice, using “never” as the reference group. We tested the same three models for each outcome separately as described above for the maternal infant feeding styles. Given that only 5 or 6 cases had missing data, if models included cases with missing data for any of the variables, then that case was excluded from the analysis (Graham et al., 1993).

RESULTS

Study Sample

Thirty-nine percent of the mothers experienced food insecurity during at least one period, including 32% during pregnancy and 19% during infancy. 12% of those households experience food insecurity during both pregnancy and infancy (Table 2). Women with household food insecurity, in particular prolonged food insecurity during both pregnancy and infancy were more likely to be non-US born, have less educational attainment, and have prenatal depressive symptoms. Women with household food insecurity were also more likely to experience other material hardships including difficulty paying bills, housing disrepair and neighborhood stress. We did not find intervention status group differences in the rates of household food insecurity during either the prenatal or infancy periods.

Table 2:

Family characteristics based on household food insecurity timing

| Food Insecurity Timing | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sample (n=410) n (%) |

Never (n=248) n (%) |

Prenatal Only (n=82) n (%) |

Infancy Only (n=30) n (%) |

Both (n=50) n (%) |

p-valuea | |

| Family characteristics | ||||||

| Non-US born | 333 (81.2) | 192 (77.4) | 66 (80.5) | 28 (93.3) | 47 (94.0) | .01* |

| Education, less than high school | 140 (34.1) | 69 (27.8) | 35 (42.7) | 14 (46.7) | 22 (44.0) | .01* |

| Marital status, single | 110 (26.8) | 60 (24.2) | 27 (32.9) | 11 (36.7) | 12 (24.0) | .25 |

| Working | 100 (24.4) | 70 (28.2) | 16 (19.5) | 7 (23.3) | 7 (14.0) | .11 |

| First child | 136 (33.2) | 88 (35.5) | 26 (31.7) | 9 (30.0) | 13 (26.0) | .58 |

| Prenatal depressive symptoms | 131 (32.1) | 58 (23.5) | 37 (45.7) | 9 (30.0) | 27 (54.0) | <.001* |

| Pre-pregnancy overweight status | 248 (60.6) | 143 (57.7) | 51 (62.2) | 22 (73.3) | 32 (65.3) | .32 |

| Material hardships | ||||||

| Difficulty paying bills | 106 (25.9) | 36 (14.5) | 35 (42.7) | 6 (20.0) | 29 (58.0) | <.001* |

| Housing disrepair | 143 (34.9) | 78 (31.5) | 24 (29.3) | 9 (30.0) | 32 (64.0) | <.001* |

| Neighborhood stress | 38 (9.3) | 13 (5.2) | 13 (15.9) | 2 (6.7) | 10 (20.0) | .001* |

We examined bivariate relationships between food insecurity timing and family characteristics and material hardships using chi square analyses.

Significant p<.05

Food Insecurity Timing and Maternal Infant Feeding Styles

Overall, mothers scored highest on responsive and restrictive feeding constructs and lowest on indulgent and laissez-faire feeding constructs (Table 1). In unadjusted analyses (Table 3; Model 1), food insecurity during both pregnancy and infancy was associated with increased pressuring (1 subscale: soothing (Cohen’s d=.59)), indulgent (3 subscales: permissive (d=.49), coaxing (d=.47) and pampering (d=.58)) and laissez-faire (1 subscale: attention (d=.61)) feeding styles. Those with food insecurity during the prenatal period only were more likely to exhibit pressuring with cereal and pressuring to soothe compared to those who never experienced food insecurity, although these relations were no longer significant in adjusted models. In models adjusting for family characteristics (Model 2), mothers experiencing food insecurity during both pregnancy and infancy were more likely to exhibit higher pressuring (1 subscale: soothing), indulgent (3 subscales: permissive, coaxing and pampering) and laissez-faire (1 subscale: attention) feeding styles than those who never experienced food insecurity. Experiencing food insecurity during both pregnancy and infancy remained independently associated with the same feeding style subscales after further adjusting for other material hardships (Model 3). Being US born (B (SE) −.74 (.15), p=<.001), completing high school (−.74 (.15), p=<.001), reporting housing disrepair (−.27 (.12), p=.03) and neighborhood stress (.43 (.20), p=.03) were independently associated with pressuring to soothe. Maternal pre-pregnancy overweight/obese status was associated with indulgent – coaxing style (−.07 (.13), p=.04) and first born was associated with indulgent – pampering style (.09 (.04), p=.01). Neighborhood stress was independently associated with laissez-faire – attention style (.32 (.11), p=.003). Depressive symptoms did not moderate the relations between food insecurity timing and feeding styles.

Table 3:

Household food insecurity timing and maternal infant feeding styles at 10 months old

| Feeding Styles Subscales | Food Insecurity Timing | Scores | Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Scores (SD) | B (SE) | p-value | B (SE) | p-value | B (SE) | p-value | ||

| Responsive – attentiond | Never | 3.95 (.86) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Prenatal only | 4.00 (.93) | .07 (.11) | .55 | .07 (.11) | .53 | .10 (.12) | .41 | |

| Infancy only | 3.71 (.75) | −.24 (.17) | .15 | −.24 (.17) | .16 | −.23 (.17) | .18 | |

| Both | 4.03 (.87) | .07 (.14) | .60 | .04 (.14) | .79 | .09 (.15) | .54 | |

| Responsive – satietye | Never | 4.45 (.51) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Prenatal only | 4.53 (.45) | .09 (.06) | .16 | .10 (.07) | .11 | .07 (.07) | .27 | |

| Infancy only | 4.47 (.44) | .02 (.10) | .81 | .03 (.10) | .80 | .02 (.10) | .83 | |

| Both | 4.40 (.52) | −.06 (.08) | .42 | −.04 (.08) | .60 | −.08 (.09) | .38 | |

| Pressuring to finishe | Never | 2.63 (.88) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Prenatal only | 2.60 (.80) | −.03 (.11) | .80 | −.03 (.11) | .76 | −.01 (.12) | .95 | |

| Infancy only | 2.71 (.93) | .07 (.17) | .66 | .07 (.17) | .66 | .08 (.17) | .65 | |

| Both | 2.83 (.80) | .18 (.14) | .19 | .12 (.14) | .39 | .18 (.15) | .22 | |

| Pressuring with cereald | Never | 2.03 (.93) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Prenatal only | 2.29 (1.00) | .26 (.12) | .04* | .20 (.12) | .10 | .19 (.13) | .13 | |

| Infancy only | 2.21 (1.06) | .18 (.19) | .33 | .16 (.18) | .38 | .16 (.18) | .37 | |

| Both | 2.32 (.91) | .28 (.15) | .06 | .24 (.15) | .11 | .24 (.16) | .13 | |

| Pressuring – soothinge | Never | 2.40 (1.12) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Prenatal only | 2.76 (1.20) | .34 (.15) | .02* | .23 (.15) | .12 | .23 (.15) | .13 | |

| Infancy only | 2.77 (1.40) | .36 (.23) | .11 | .17 (.22) | .45 | .17 (.22) | .44 | |

| Both | 3.07 (1.13) | .68 (.18) | <.001* | .49 (.18) | .01* | .60 (.19) | .002* | |

| Restrictive – amount consumede | Never | 3.88 (1.06) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Prenatal only | 3.90 (1.04) | .02 (.14) | .87 | .002 (.14) | .99 | .02 (.14) | .89 | |

| Infancy only | 4.05 (.97) | .16 (.20) | .42 | .11 (.21) | .58 | .12 (.21) | .58 | |

| Both | 3.88 (1.12) | −.01 (.17) | .96 | −.03 (.17) | .87 | −.02 (.18) | .93 | |

| Restrictive – diet qualityd | None | 4.20 (.68) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Prenatal only | 4.21 (.58) | −.003 (.08) | .97 | .003 (.09) | .97 | −.03 (.09) | .71 | |

| Infancy only | 4.18 (.63) | −.02 (.13) | .88 | −.002 (.13) | .99 | −.01 (.13) | .91 | |

| Both | 4.06 (.69) | −.11 (.10) | .27 | −.10 (.11) | .34 | −.13 (.12) | .27 | |

| Indulgent – permissivee | Never | 1.34 (.45) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Prenatal only | 1.39 (.47) | .06 (.06) | .30 | .07 (.06) | .27 | .06 (.06) | .36 | |

| Infancy only | 1.49 (.57) | .15 (.09) | .10 | .17 (.09) | .06 | .18 (.09) | .05 | |

| Both | 1.57 (.49) | .23 (.07) | .002* | .23 (.08) | .003* | .20 (.08) | .02* | |

| Indulgent – coaxinge | Never | 1.12 (.30) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Prenatal only | 1.15 (.32) | .03 (.04) | .42 | .03 (.04) | .53 | .04 (.04) | .38 | |

| Infancy only | 1.21 (.35) | .09 (.06) | .14 | .09 (.06) | .14 | .10 (.06) | .12 | |

| Both | 1.27 (.35) | .14 (.05) | .01* | .13 (.05) | .01* | .14 (.05) | .01* | |

| Indulgent – soothinge | Never | 1.13 (.31) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Prenatal only | 1.16 (.34) | .04 (.04) | .36 | .03 (.04) | .48 | .04 (.04) | .40 | |

| Infancy only | 1.15 (.27) | .02 (.06) | .80 | .01 (.06) | .86 | .02 (.06) | .81 | |

| Both | 1.24 (.33) | .09 (.05) | .06 | .08 (.05) | .12 | .08 (.05) | .12 | |

| Indulgent – pamperinge | Never | 1.13 (.32) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Prenatal only | 1.16 (.31) | .03 (.04) | .41 | .03 (.04) | .54 | .03 (.04) | .47 | |

| Infancy only | 1.18 (.32) | .05 (.06) | .47 | .04 (.06) | .49 | .05 (.06) | .47 | |

| Both | 1.32 (.34) | .18 (.05) | <.001* | .16 (.05) | .002* | .16 (.06) | .004* | |

| Laissez-faire – attentione | Never | 1.48 (.55) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Prenatal only | 1.61 (.71) | .14 (.08) | .09 | .10 (.08) | .23 | .09 (.08) | .28 | |

| Infancy only | 1.66 (.78) | .18 (.12) | .15 | .16 (.12) | .18 | .17 (.12) | .16 | |

| Both | 1.89 (.77) | .38 (.10) | <.001* | .32 (.10) | .002* | .29 (.11) | .01* | |

| Laissez-faire – diet qualityd | Never | 1.69 (.59) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Prenatal only | 1.73 (.71) | .05 (.08) | .55 | .02 (.08) | .83 | .04 (.09) | .65 | |

| Infancy only | 1.86 (.64) | .17 (.12) | .16 | .17 (.12) | .17 | .18 (.12) | .15 | |

| Both | 1.81 (.68) | .10 (.10) | .29 | .08 (.10) | .44 | .13 (.11) | .25 | |

Model 1: Unadjusted.

Model 2: Adjusting for covariates including country of birth (US born, non-US born), educational attainment (less than high school, high school graduate), marital status (married/living as married, single/divorced/widowed), having other children (no, yes), working (no, yes), prenatal depressive symptoms (no, yes), and pre-pregnancy overweight/obese (no, yes) and intervention group status.

Model 3: Adjusting for covariates from Model 2 and other material hardships (difficulty paying bills, housing disrepair and neighborhood stress).

Model included sample size of n=406.

Model included sample size of n=407.

Significant p<.05

Food insecurity Timing and Maternal Infant Feeding Practices

Mothers with food insecurity prenatal only reported less infant vegetable intake (AOR .45, p=.01) and greater juice intake (AOR 1.95, p=.04) compared to mothers who never experienced food insecurity even after adjusting for family characteristics and other material hardships (Table 4). Mothers with food insecurity during both pregnancy and infancy reported decreased infant self-feeding (AOR .30, p=.01) compared to those who never experienced food insecurity. Breastfeeding as the only milk source, fruit intake, and eating family meals together were not related to food insecurity.

Table 4:

Household food insecurity timing and maternal infant feeding practices at 10 months olda

| Infant Feeding Practices | Food Insecurity Timing | Sample | Model 1b | Model 2c | Model 3d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | OR | p-value | AOR | p-value | AOR | p-value | ||

| Breastfeeding | Never | 71 (29.8) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Prenatal only | 16 (19.5) | .58 | .08 | .59 | .11 | .60 | .13 | |

| Infancy only | 11 (36.7) | 1.35 | .45 | 1.39 | .44 | 1.41 | .43 | |

| Both | 14 (28.0) | .84 | .63 | .79 | .54 | .83 | .65 | |

| Daily fruit intake | Never | 205 (82.7) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Prenatal only | 68 (82.9) | .98 | .95 | 1.05 | .90 | 1.03 | .95 | |

| Infancy only | 24 (80.0) | .82 | .68 | .88 | .80 | .92 | .86 | |

| Both | 38 (76.0) | .63 | .22 | .70 | .38 | .57 | .20 | |

| Daily vegetable intake | Never | 181 (73.0) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Prenatal only | 45 (54.9) | .47 | .004* | .46 | .01* | .45 | .01* | |

| Infancy only | 17 (56.7) | .49 | .07 | .51 | .09 | .49 | .08 | |

| Both | 31 (62.0) | .59 | .10 | .59 | .12 | .63 | .22 | |

| Juice intake ever | Never | 158 (63.7) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Prenatal only | 65 (79.3) | 2.16 | .01* | 2.06 | .02* | 1.95 | .04* | |

| Infancy only | 23 (76.7) | 1.88 | .16 | 2.02 | .14 | 2.08 | .13 | |

| Both | 34 (68.0) | 1.18 | .61 | 1.07 | .84 | .92 | .83 | |

| Self-feeding with fingers | Never | 227 (91.5) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Prenatal only | 77 (93.9) | 1.41 | .50 | 1.58 | .39 | 1.75 | .32 | |

| Infancy only | 29 (96.7) | 2.70 | .34 | 3.12 | .29 | 3.43 | .25 | |

| Both | 38 (76.0) | .29 | .002* | .28 | .004* | .30 | .01* | |

| Daily family meals together | Never | 188 (75.8) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Prenatal only | 60 (73.2) | .84 | .55 | .96 | .91 | .88 | .70 | |

| Infancy only | 25 (83.3) | 1.57 | .38 | 1.68 | .33 | 1.63 | .35 | |

| Both | 37 (74.0) | .87 | .69 | 1.03 | .93 | 1.00 | .99 | |

All models included sample size of n=407.

Model 1: Unadjusted.

Model 2: Adjusting for covariates including country of birth (US born, non-US born), educational attainment (less than high school, high school graduate), marital status (married/living as married, single/divorced/widowed), having other children (no, yes), working (no, yes), prenatal depressive symptoms (no, yes), and pre-pregnancy overweight/obese (no, yes) and intervention group status.

Model 3: Adjusting for covariates from Model 2 and other material hardships (difficulty paying bills, housing disrepair and neighborhood stress).

Significant p<.05

DISCUSSION

Our study of low-income Hispanic mother-infant pairs found that experiencing prolonged household food insecurity during both pregnancy and infancy significantly increased non-responsive maternal infant feeding styles at infant age 10 months. In particular, experiencing food insecurity during both pregnancy and infancy was associated with pressuring, indulgent and laissez-faire feeding styles. Prolonged food insecurity was also associated with decreased infant self-feeding. Prenatal food insecurity was associated with less infant vegetable intake and more juice intake. These relations remained significant after adjusting for family characteristics and other material hardships, highlighting that the relations with prolonged food insecurity are not simply confounded by other poverty-associated hardships.

Maternal child feeding styles, adapted from research on general parenting styles, are based on the balance between responsiveness to child cues and behavioral control. Non-responsive feeding styles, including pressuring, restrictive, indulgent and laissez-faire, that fail to respond appropriately to child feeding cues or to set healthy limits, have all been associated with child weight (Frankel et al., 2014; Hennessy et al., 2010; Hughes et al., 2008; Tovar et al., 2012; Vollmer & Mobley, 2013). Pressuring is often related to lower infant weight-for-age and restriction to higher weight-for-age (Thompson et al., 2013), and these styles are commonly associated with concern for the child being underweight and overweight respectively (Gross et al., 2011). Studies of low-income Hispanic families found that indulgent maternal infant feeding styles have been most associated with higher child weight status in both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies of pre-school aged children (Frankel et al., 2014; Hennessy et al., 2010; Hughes et al., 2016; Tovar et al., 2012). Overall, non-responsive feeding styles may represent a potentially critical mediator of poverty-related disparities in early child obesity since they are more prevalent in low-income ethnic minority mothers beginning in early infancy (Hughes et al, 2005; Tovar et al., 2012; Vollmer & Mobley, 2013). However, the mechanism through which poverty during sensitive periods of pregnancy and infancy relates to these feeding styles remains unclear.

Poverty during the prenatal and infancy periods has been associated with multiple stressors known to adversely impact child growth. Food insecurity represents a commonly experienced stressor for families living in poverty that increases the risk factors associated with childhood obesity. Food insecurity during pregnancy has been associated with higher rates of gestational weight gain, gestational diabetes mellitus, disordered eating, and dietary fat intake postpartum (Laraia et al., 2010; Laraia et al., 2015). In addition to impacts on the pregnant women’s diet and weight, prenatal food insecurity has been associated with higher prenatal stress and obesity-promoting infant feeding attitudes (Gross et al., 2016a; Laraia et al., 2015). Prenatal food insecurity has been associated with a lower internal locus of control over the prevention of child obesity (Gross et al., 2016a). Lower self-efficacy associated with food insecurity has been related to increased controlling feeding styles (Salarkia et al., 2016) and decreased provision of fruits and vegetables to their children (Hilmers et al., 2012). Focusing on strengthening parenting self-efficacy during pregnancy for women with food insecurity may help to prevent the development of non-responsive feeding styles.

Household food insecurity during infancy has been associated with key aspects of parenting related to childhood obesity (Bronte-Tinkew et al., 2007). We previously found that food insecurity reported by WIC participants with infants in the first six months of life was associated with increased pressuring and restrictive maternal infant feeding styles (Gross et al., 2012). These relations were mediated by maternal concern for her child becoming overweight in the future. However, indulgent and laissez-faire styles were not assessed at that time and household food insecurity during pregnancy was unknown. No prior studies to our knowledge have directly assessed how food insecurity during both pregnancy and infancy relates to non-responsive maternal infant feeding styles in the older infant, a period when infant feeding involves the transition to more solid foods and self-feeding.

This current study found that prolonged food insecurity, or the additive effects of experiencing food insecurity during both pregnancy and infancy, was most associated with non-responsive feeding styles at infant age 10 months. Perhaps pressuring and indulgent styles were most related because mothers were trying to compensate for concerns about not having enough food, either by encouraging infants to eat more when food is available or encouraging feeding to soothe infants to keep them from crying by giving them what they want. The feeding style of using food to soothe which has been documented in food insecure households, has been related to excess infant weight gain. Prior studies of mothers observed to use food to soothe during laboratory visits at infant age 6, 12 and 18 months old were more likely to have infants with excess weight gain compared to infants of mothers who did not feed to soothe (Stifter & Moding, 2015). Pressuring to soothe specifically focuses on immediately feeding when infants cry. This style therefore may fail to consider that not all crying means hunger and that alternative methods of soothing can sometimes be tried prior to feeding (Gross et al., 2010). Greater uninvolved or laissez-faire feeding styles have also been related to maternal stress, which may potentially mediate the relations between food insecurity and laissez-faire feeding styles (Barrett et al., 2016; Hughes et al., 2015). Qualitative research is needed to better understand how the experience of household food insecurity during pregnancy and infancy shapes maternal attitudes and beliefs, and the development of specific feeding styles.

The extent to which prolonged food insecurity has adverse effects on child growth may be related to the duration, intensity, timing, and context of the stressful experience. Studies are needed to determine how even under stressful conditions, supportive, responsive parenting may be enhanced and whether decreasing non-responsive feeding styles would prevent or even reverse the harmful effects of toxic stressors, like household food insecurity. Further study is needed to determine if food insecurity is screened for and identified during pregnancy, whether interventions to prevent food insecurity from persisting into infancy could mitigate the development of obesity-promoting maternal infant feeding styles. A strength of this study is that given that associations between food insecurity and feeding styles were only found when food insecurity occurred in both pregnancy and infancy, screening during only one time point is probably is not sufficient to understanding these relations. Although moderate effect size differences were detected, the clinical impact of these associations on later weight trajectories remains unclear. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine the role that household food insecurity during these sensitive periods plays in the development of later child feeding practices and child growth trajectories.

While our findings support the relations between household food insecurity and maternal infant feeding styles at 10 months, fewer associations with feeding practices were found. While studies of food insecurity and feeding practices in older children found that food insecure households consume more low-cost, high-energy-dense foods (Drewnowski et al., 2004), previous study of infant feeding practices revealed no associations with breastfeeding, introducing juice, and adding cereal to the bottle based on household food security status in the first six months of life (Gross et al., 2012). Given that maternal feeding practices may vary depending on the infant’s developmental stage, longitudinal research is needed to better understand how household food insecurity relates to feeding practices across the life course. In addition, our findings that food insecurity during pregnancy was associated with less infant vegetable intake and more juice intake, highlights the need to include prenatal assessments in future studies.

This study has several limitations. First, our sample was a cohort of low-income Hispanic women, which might limit generalizability to all pregnant women and mothers. The food insecurity variables provide information about the timing and duration of household food insecurity during separate 12-month periods encompassing pregnancy and the first year of life. However, we were not able to determine whether the severity of food insecurity fluctuated during the 12-month periods assessed. Another potential limitation is that food insecurity, other material hardships and feeding styles and practices were measured using maternal report instead of direct observation, possibility introducing social desirability bias. Although analyses adjusted for a range of potential confounders, other unmeasured family and community level confounders might exist. Following the cohort longitudinally throughout the child’s first 3 years of life will help to determine how food insecurity during these early sensitive periods will affect later feeding styles and practices and ultimately child growth trajectories.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study of low-income Hispanic mother-infant pairs found that experiencing prolonged household food insecurity during both pregnancy and infancy significantly increased obesity-promoting non-responsive maternal infant feeding styles at infant age 10 months. These findings highlight the importance of developing effective prevention strategies which span sensitive time points in the life course. Prenatal and pediatric primary care may represent a universal platform for food insecurity screening and referral to nutrition assistance programs. Our results indicate that if food insecurity is identified during pregnancy, interventions to prevent it from persisting into infancy may mitigate the development of obesity-promoting maternal infant feeding styles and practices. Future research studies should explore how early obesity prevention programs that begin during pregnancy could incorporate food insecurity screening and the provision of community resources as part of their intervention.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Starting Early Program staff who contributed to this project. This work was supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, US Department of Agriculture, award number 2011-68001-30207, and the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development through a K23 Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award (K23HD081077; PI Gross). These funding sources had no involvement in conducting the research or in preparing this article.

REFERENCES

- Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA Jr, & Briefel RR (2001). Food insufficiency, family income, and health in US preschool and school-aged children. American Journal of Public Health, 91(5), 781–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SA (1990). Core indicators of nutritional state for difficult-to-sample populations. Journal of Nutrition, 120(Suppl 11), 1559–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett KJ, Thompson AL, & Bentley ME (2016). The influence of maternal psychosocial characteristics on infant feeding styles. Appetite, 103, 396–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel G, Nord M, Price C, Hamilton W, & Cook J (2000). Guide to measuring household food security. Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture. [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL, Fisher JA. Appetite and eating behavior in children. (1995) Pediatr Clin North Am, 42(4), 931–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL, Davison KK. Family environmental factors influencing the developing behavioral controls of food intake and childhood overweight. (2001) Pediatr Clin North Am, 48(4), 893–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blissett J Relationships between parenting style, feeding style and feeding practices and fruit and vegetable consumption in early childhood. (2011) Appetite, 57(3), 826–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P, Marchi K, Egerter S, Kim S, Metzler M, Stancil T, et al. (2010). Poverty, near-poverty, and hardship around the time of pregnancy. Maternal & Child Health Journal, 14(1), 20–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronte-Tinkew J, Zaslow M, Capps R, Horowitz A, & McNamara M (2007). Food insecurity works through depression, parenting, and infant feeding to influence overweight and health in toddlers. Journal of Nutrition, 137(9), 2160–2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SJ, Andrews MS, Bickel GW (1999) Measuring Food Insecurity and Hunger in the United States: Development of a National Benchmark Measure and Prevalence Estimates. J. Nutr 129: 510S–516S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey PH, Simpson PM, Gossett JM, Bogle ML, Champagne CM, Connell C, et al. (2006). The association of child and household food insecurity with childhood overweight status. Pediatrics, 118(5), e1406–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey PH, Szeto K, Lensing S, Bogle M, & Weber J (2001). Children in food-insufficient, low-income families: Prevalence, health, and nutrition status. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 155(4), 508–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JT, Frank DA, Berkowitz C, Black MM, Casey PH, Cutts DB, et al. (2004) Food Insecurity Is Associated with Adverse Health Outcomes among Human Infants and Toddlers. The Journal of Nutrition, 134 (6), 1432–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo PR, Woody EZ. Domain-specific parenting styles and their impact on the child’s development of particular deviance: The example of obesity proneness. (1985) J Soc Clin Psychol, 3, 425–445. [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A, Specter SE. Poverty and obesity: the role of energy density and energy costs. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(1):6–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiSantis KI, Hodges EA, Johnson SL, & Fisher JO (2011). The role of responsive feeding in overweight during infancy and toddlerhood: A systematic review. International Journal of Obesity, 35(4), 480–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois L, Farmer A, Girard M, & Porcherie M (2006). Family food insufficiency is related to overweight among preschoolers. Social Science & Medicine, 63(6), 1503–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell P, Thow AM, Abimbola S, Faruqui N, & Negin J (2017) How food insecurity could lead to obesity in LMICs. Health Promotion International, 1–15. 10.1093/heapro/dax026 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fein SB, Labiner-Wolfe J, Shealy KR, Li R, Chen J, Grummer-Strawn LM. (2008) Infant feeding practices study II: study methods. Pediatrics, 122, S28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg E, Kavanagh PL, Young RL, & Prudent N (2008). Food insecurity and compensatory feeding practices among urban black families. Pediatrics, 122(4), e854–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel LA, O’Connor TM, Chen T, Nicklas T, Power TG, & Hughes SO (2014). Parents’ perceptions of preschool children’s ability to regulate eating. Feeding style differences. Appetite, 76, 166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Donaldson SI (1993). Evaluating interventions with differential attrition: The importance of nonresponse mechanisms and use of follow-up data. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(1), 119–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross RS, Fierman AH, Rosenberg TJ, Scheinmann R, Chiasson MA, Mendelsohn AL, Messito MJ Maternal Perceptions of Infant Hunger, Satiety and Pressuring Feeding Styles in an Urban Latina WIC Population. (2010) Academic Pediatrics, 10(1), 29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross RS, Mendelsohn AL, Fierman AH, & Messito M (2011). Maternal controlling feeding styles during early infancy. Clinical Pediatrics, 50(12), 1125–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross R, Mendelsohn A, Gross M, Scheinmann R, & Messito M (2016). Material hardship and internal locus of control over the prevention of child obesity in low-income Hispanic pregnant women. Academic Pediatrics, 16(5), 468–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross R, Mendelsohn A, Gross M, Scheinmann R, & Messito M (2016). Randomized controlled trial of a primary care-based child obesity prevention intervention on infant feeding practices. Journal of Pediatrics, 174, 171–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross R, Mendelsohn A, Yin H, Tomopoulos S, Gross M, Scheinmann R, et al. (2017). Randomized controlled trial of an early child obesity prevention intervention: Impacts on infant tummy time. Obesity (Silver Spring), 25(5), 920–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross RS, Mendelsohn AL, Fierman AH, Racine AD, & Messito MJ (2012). Food insecurity and obesogenic maternal infant feeding styles and practices in low-income families. Pediatrics, 130(2), 254–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy E, Hughes SO, Goldberg JP, Hyatt RR, & Economos CD (2010). Parent behavior and child weight status among a diverse group of underserved rural families. Appetite, 54(2), 369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy E, Hughes SO, Goldberg JP, Hyatt RR, Economos CD. Permissive parental feeding behavior is associated with an increase in intake of low-nutrient-dense foods among American children living in rural communities. (2012) Journal of the Academy of Nutrition & Dietetics, 112(1), 142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilmers A, Cullen K, Moore C, & and O’Connor T (2012). Exploring the association between household food insecurity, parental self-efficacy, and fruit and vegetable parenting practices among parents of 5- to 8-year-old overweight children. Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, 3(1) [Google Scholar]

- Hughes S, Power T, O’Connor T, Orlet Fisher J, & Chen T (2016). Maternal feeding styles and food parenting practices as predictors of longitudinal changes inweight status in Hispanic preschoolers from low-income families. Journal of Obesity, 2016, 7201082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes SO, Power TG, Liu Y, Sharp C, & Nicklas TA (2015). Parent emotional distress and feeding styles in low-income families. The role of parent depression and parenting stress. Appetite, 92, 337–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes SO, Power TG, Orlet Fisher J, Mueller S, & Nicklas TA (2005). Revisiting a neglected construct: Parenting styles in a child-feeding context. Appetite, 44(1), 83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes SO, Shewchuk RM, Baskin ML, Nicklas TA, & Qu H (2008). Indulgent feeding style and children’s weight status in preschool. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 29(5), 403–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley KM, Black MM, Papas MA, & Caulfield LE (2008). Maternal symptoms of stress, depression, and anxiety are related to nonresponsive feeding styles in a statewide sample of WIC participants. Journal of Nutrition, 138(4), 799–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley KM, Cross MB, & Hughes SO (2011). A systematic review of responsive feeding and child obesity in high-income countries. Journal of Nutrition, 141(3), 495–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivers LC, & Cullen KA. (2011). Food insecurity: Special considerations for women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 94(6), 1740S–1744S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Cohen J, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Pawlby SJ, & Caspi A (2005). Maternal depression and children’s antisocial behavior: Nature and nurture effects. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(2), 173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JB (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski RJ, Carroll MD, Flegal KM, & Troiano RP (1997). Varying body mass index cutoff points to describe overweight prevalence among U.S. adults: NHANES III (1988 to 1994). Obesity Research, 5(6), 542–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laraia BA, Siega-Riz AM, Gundersen C, & Dole N. (2006). Psychosocial factors and socioeconomic indicators are associated with household food insecurity among pregnant women. Journal of Nutrition, 136(1), 177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laraia BA, Siega-Riz AM, & Gundersen C (2010). Household food insecurity is associated with self-reported pregravid weight status, gestational weight gain, and pregnancy complications. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 110(5), 692–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laraia B, Vinikoor-Imler LC, & Siega-Riz AM (2015). Food insecurity during pregnancy leads to stress, disordered eating, and greater postpartum weight among overweight women. Obesity, 23(6), 1303–1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheson DM, Varady J, Varady A, Killen JD. Household food security and nutritional status of Hispanic children in the fifth grade. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76(1):210–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheson DM, Robinson TN, Varady A, Killen JD. Do Mexican-American mothers’ food related parenting practices influence their children’s weight and dietary intake? J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(11):1861–1865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metallinos-Katsaras E, Sherry B, & Kallio J (2009). Food insecurity is associated with overweight in children younger than 5 years of age. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 109(10), 1790–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk C, Spicer J, & Champagne FA (2012). Linking prenatal maternal adversity to developmental outcomes in infants: The role of epigenetic pathways. Development & Psychopathology, 24(4), 1361–1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L (1992). The impact of postnatal depression on infant development. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines, 33(3), 543–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nord M, & Hopwood H (2007). Recent advances provide improved tools for measuring children’s food security. Journal of Nutrition, 137(3), 533–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TM, Hughes SO, Watson KB, et al. Parenting practices are associated with fruit and vegetable consumption in pre-school children. (2010) Public Health Nutr, 13(1), 91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick H, Nicklas TA, Hughes SO, Morales M. The benefits of authoritative feeding style: Caregiver feeding styles and children’s food consumption patterns. (2005) Appetite, 44(2), 243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP. Garner AS. Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care. Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman HB, Gilbert BC, Msphbrenda CG, & Lansky A (2006). The pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system (PRAMS): Current methods and evaluation of 2001 response rates. Public Health Reports, 121(1), 74–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stifter CA, & Moding KJ (2015). Understanding and measuring parent use of food to soothe infant and toddler distress: A longitudinal study from 6 to 18 months of age. Appetite, 95, 188–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suglia SF, Duarte CS, Chambers EC, & Boynton-Jarrett R (2013). Social and behavioral risk factors for obesity in early childhood. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 34(8), 549–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taveras EM, Scanlon KS, Birch L, Rifas-Shiman SL, Rich-Edwards JW, Gillman MW. Association of breastfeeding with maternal control of infant feeding at age 1 year. (2004) Pediatrics, 114(5), e577–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson AL, Mendez MA, Borja JB, Adair LS, Zimmer CR, & Bentley ME (2009). Development and validation of the infant feeding style questionnaire. Appetite, 53(2), 210–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson AL, Adair LS, & Bentley ME (2013). Pressuring and restrictive feeding styles influence infant feeding and size among a low-income African-American sample. Obesity, 21(3), 562–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tovar A, Hennessy E, Pirie A, Must A, Gute DM, Hyatt RR, et al. (2012). Feeding styles and child weight status among recent immigrant mother-child dyads. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition & Physical Activity, 9, 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census. (1997). Survey of Income and program participation (SIPP) 1993 panel, longitudinal file. ICPSR version: U.S. dept. of commerce, bureau of the census [producer]. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the Census [producer]. [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer RL, & Mobley AR (2013). Parenting styles, feeding styles, and their influence on child obesogenic behaviors and body weight. A review. Appetite, 71, 232–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood CT, Perreira KM, Perrin EM, Yin HS, Rothman RL, Sanders LM, et al. (2016). Confirmatory factor analysis of the infant feeding styles questionnaire in Latino families. Appetite, 100, 118–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]