Abstract

Starting a new lab in mechanobiology and a new lab in general can be an exciting, yet daunting experience. Depending on your previous position, you have now found yourself with significantly more responsibility in more ways than one. For those considering taking such a career path, I present in this commentary advice that will hopefully be useful and provide food for thought.

Keywords: Mechanobiology, New principal investigator, Cardiovascular system, Gut epithelium

Persistence is key

Persistence always wins the battle. As a new PI, you will be given start-up funds. However, these funds will only last for so long. While this of course is obvious, what may not be so obvious is that you may have to take time to be patient before you are successful. Keep applying and be persistent something will eventually come through.

Do not let fear prevent you from doing great work

I will start off with a quote from a famous Hall of Famer athlete “You miss 100% of the shots you don’t take.” You will never know if you have a chance to get a grant if you do not apply. You will receive your fair share of comments from reviewers that will judge the work you have proposed in a less than flattering manner. Such an experience can be discouraging and can sometimes make you question your work. Everyone goes through this to some extent, but do not let your fear of what someone else may think or say about your work discourage you. Each time you submit a proposal or article you are in essence revealing your thoughts, which are a reflection of who you are as a person, thus making you vulnerable. It takes courage to constantly submit your ideas knowing that there is a good chance your ideas will be rejected. Do not be afraid to be vulnerable as it is when we truly do this with no inhibitions that we achieve the most success.

Take time for yourself

As a new PI of a lab, you have probably been programed like I was to have long work days. You do this because you are willing to do whatever it takes to achieve your research and career goals. Unfortunately, this can happen at the expense of your personal life. I will say that it is worth holding off on an experiment or editing a paper to be with family or friends as this is what is most important. Even if you need time to be alone away from work, this is helpful as well. Work will always be there.

Set goals, follow them, but also be flexible

My final piece of advice would be to set goals and do your best to achieve them. For me personally, I set goals for each semester. Whether it is a research goal or publication goal, I even set hard deadlines with dates that I put on my calendar. Keeping in mind that you have to run a research lab in addition to having a personal life, sometimes, circumstances out of your control happen and you may have to alter your plans. Do not panic when this happens; just adjust your goals accordingly. The advice I have given above is a result of the collective experiences I have had during my career, which is reflected in my background.

Background

My career path began at a historically black university called Clark Atlanta University (Clark) where I received my B.S. in Mechanical Engineering. It was during my time at Clark that I was fortunate to become a NIH MARC U-STAR scholar, which allowed me have my first experience in mechanobiology (Wang and Thampatty 2006) at the University of Maryland during a summer internship. After completion of my studies at Clark, I entered a doctoral program in mechanical engineering at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) where I worked in the cellular biomechanics lab. Working in the cellular biomechanics lab really confirmed my desire to work in the field as I was truly fascinated with learning how mechanics can play a role in human physiology and pathology. After completing my PhD at CMU, I worked in the Laboratory for Molecular and Integrative Cellular Dynamics at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health where I again received excellent mentoring and increased my knowledge in the field. I am now an assistant professor in the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at the University of Central Florida where I have been running the Cellular Mechanobiology lab (Fig. 1) for 4 years. My research interest includes investigating the mechanics of the cardiovascular system (Islam and Steward Jr 2018; Islam et al. 2017; Warren et al. 2016; Wu et al. 2017), cerebrovascular system, neurovascular unit, and gut epithelium. My lab is currently funded by the NIH.

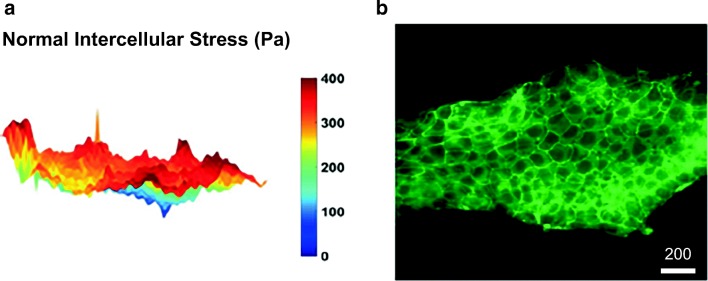

Fig. 1.

Normal intercellular stress

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Islam M, Steward RL., Jr Probing endothelial cell mechanics through connexin 43 disruption. Exp Mech. 2018;59:327–336. doi: 10.1007/s11340-018-00445-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam Md. Mydul, Beverung Sean, Steward Jr. Robert. Bio-Inspired Microdevices that Mimic the Human Vasculature. Micromachines. 2017;8(10):299. doi: 10.3390/mi8100299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JH, Thampatty BP. An introductory review of cell mechanobiology. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2006;5:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10237-005-0012-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren Kristin M., Islam Md. Mydul, LeDuc Philip R., Steward Robert. 2D and 3D Mechanobiology in Human and Nonhuman Systems. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 2016;8(34):21869–21882. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b12064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, LeDuc P, Steward RL Jr (2017) How can we predict cellular mechanosensation?: comment on “Cellular mechanosensing of the biophysical microenvironment: a review of mathematical models of biophysical regulation of cell responses” by Bo Cheng et. al Phys Life Rev [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]