Abstract

Objectives

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common disorder influenced by genetic and environmental factors. Mutations of AT-hook DNA-binding motif containing 1 (AHDC1) gene have been implicated which could cause rare syndromes presenting OSA. This study aims to investigate some rare mutations of AHDC1 in Chinese Han individuals with OSA.

Patients and Methods

Three hundred and seventy-five patients with OSA and one hundred and nine control individuals underwent polysomnography. A targeted sequencing experiment was taken in 100 patients with moderate-to-severe OSA, and genotyping was taken in 157 moderate-to-severe OSA and 100 control individuals. The effect of mutations was validated by the luciferase reporter assay.

Results

One rare missense mutation (AHDC1: p.G1484D) and two mutations (c.-88C>T; c.-781C>G) in 5′-untranslated region (UTR) of AHDC1 were identified. The rare mutation (c.-781C>G) in 5′-UTR that was identified in several patients presenting more severe clinical manifestations affects expression of AHDC1. Conclusions. Our results revealed three rare mutations of AHDC1 in patients with OSA in Chinese Hanindividuals.

1. Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA, OMIM 107650) is an increasingly common disorder, and it is characterized by repeated upper airway collapse during sleep that results in chronic intermittent hypoxia, hypercapnia, and sleep fragmentation [1, 2]. Affected individuals are at increased risks of cardiovascular disease, stroke, and other disorders [1]. However, the pathogenesis of OSA is unclear, so better understanding of the etiology of OSA is needed.

OSA is caused by multiple factors, most commonly obesity, muscle dysfunction, craniofacial abnormalities, and genetic predisposition [3–6]. Some Mendelian diseases also present OSA clinical features, such as auriculo-condylar syndrome [7], Costello syndrome [8], Xia–Gibbs syndrome [9], and Marfan syndrome [10]. OSA aggregates within families, having a first-degree relative with OSA increases risk of OSA by more than 1.5-fold [3]. Furthermore, approximately 35% to 40% of apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) which is the most common disease-defining metric for OSA may be explained by genetic factors [4, 11–14]. Simultaneously, from the pathological viewpoint, sympathetic nervous system activity, fat distribution, upper airway dilator muscle dysfunction, craniofacial development, heightened chemosensitivity, and a low arousal threshold may cause OSA [15, 16], whereas these pathological processes are also regulated by genes [17].

AT-hook DNA-binding motif containing 1 (AHDC1) gene is located on chromosome 1p36.11 and encodes 1603 amino acid protein AT‐hook DNA-binding motif-containing protein 1. And AHDC1 is nearby AT-rich interaction domain 1A (ARID1A) gene, mutations in which cause autosomal-dominant Coffin-Siris syndrome, and its symptoms are maxillary hypoplasia, tongue cleft, poor alignment of teeth, etc. OSA could coexist with spinocerebellar ataxia type 1, which is a hereditary disease of the nervous system regulated by AHDC1. Abnormalities of AHDC1 probably cause pharyngeal dilator muscle incoordination, thereby leading to airway collapse [9, 18, 19]. Moreover, mutations in AHDC1 have been implicated to most likely cause Xia‐Gibbs syndrome. And Xia‐Gibbs syndrome presented OSA, language delay, and hypotonia. [9]. Two missense mutations in AHDC1 were found to be associated with schizophrenia and oral developmental disorders that might lead to upper airway dysfunction and perhaps OSA [20, 21]. Nevertheless, if there were any rare mutations in AHDC1 associated with OSA in Chinese Han is not clear.

The purpose of this study is to investigate rare mutations of AHDC1 in Chinese Han individuals with OSA. In this study, we used targeted sequencing which is a cost-efficient tool [22] to discover rare mutations of AHDC1 in unrelated Chinese Han individuals with OSA.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Patients

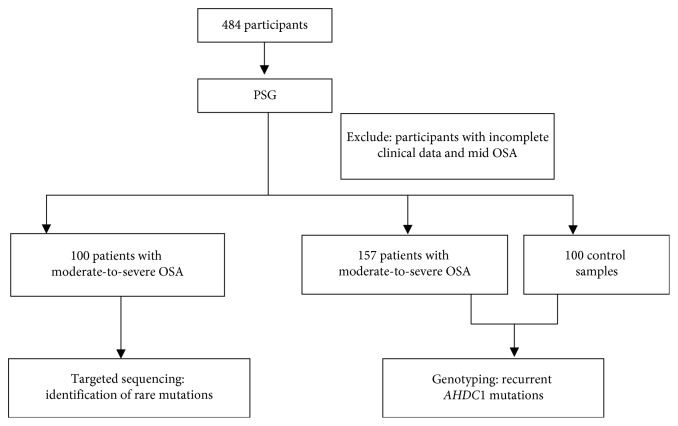

Subjects for sequencing came from patients at the Otolaryngological Department of Beijing An Zhen Hospital from February 2017 to December 2017. All participants were subjects of self-reported snoring symptoms; each subject completed OSA screening and was scheduled for an overnight sleep study. The sleep study was conducted using a level II portable diagnostic device (SOMNOscreen; SOMNOmedics GmbH, Randersacker, Germany) approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. In total, 484 unrelated Chinese Han adults aged ≥18 years were recruited, including 375 patients with OSA and 109 control individuals. After excluding participants with incomplete clinical data and mild OSA, a targeted sequencing experiment was taken in 100 patients with moderate-to-severe OSA. To identify additional mutation carriers, we genotyped an expanded cohort of 157 moderate-to-severe OSA and 100 control individuals. The study flow chart is shown in Figure 1. Patients with OSA and control individuals were unrelated individuals diagnosed using the American Academy of Sleep Medicine guidelines [23]. All participants underwent a complete examination, and their medical history and basic clinical and biochemical variables were collected. No participants had lung, kidney, liver, or nervous system disease.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart. PSG: polysomnography; OSA: obstructive sleep apnea.

All participants completed an informed consent before enrollment. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Beijing An Zhen Hospital (2017005), adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki, and was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Register (ChiCTR-ROC-17011027).

2.2. Phenotype Definitions

The diagnostic standard of OSA is defined as AHI more than 5 times per hour, and this standard is further subdivided into mild (5 < AHI ≤ 15 events/hour), moderate (15 < AHI ≤ 30 events/hour), and severe (AHI > 30 events/hour) [24]. The quantitative phenotypic outcomes were the AHI (defined by events associated with ≥3% desaturation), the lowest oxygen saturation (LSaO2) and mean oxygen saturation (MSaO2) across the sleep period. These quantitative phenotypic outcomes excluded intermittent waking episodes [25].

Covariates were obtained by questionnaires and direct measurement. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the standard BMI formula: body mass (in kilograms) divided by square of height (in meters). Hypertension is defined as having higher blood pressure than normal three times without antihypertensive drugs, i.e., systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg. All blood samples were collected after participants had fasted overnight. Venous blood sample was obtained before 9 am. Clinical variables included total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and fasting blood glucose (GLU). Serum TC, TG, HDL-C, LDL-C, GLU, and other routine serum biochemical parameters were measured using a biochemical analyzer (Hitachi-7600; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Blood samples were stored in a freezer at −80°C. All measurements were obtained using blinded quality control specimens at the Department of the Biochemical Laboratory at Beijing An Zhen Hospital. All results were interpreted by a specialist.

2.3. Exome Sequencing Analysis

The genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood (details are described in the Methods section in the appendix). A custom-designed gene panel containing AHDC1 (Supplementary ) was ordered from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA) for targeted sequencing. The coverage of panel is 99.52% (Supplementary ). Details regarding primers and resequencing procedures are given in Supplementary and the Methods section in the appendix.

The read alignments were filtered by the software into mapped BAM-files using the reference genomic sequence (hg19) of the target genes. Annotation of variants was performed using Ion Reporter Software (Version 4.4; Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany) for the variant call format files. The annotation included genomic and complementary DNA positions, genetic reference sequences, amino acid changes, and related information available from public databases, such as the 1000 Genomes Project; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grand Opportunity Exome Sequencing Project (ESP6500) (https://esp.gs.washington.edu/drupal/); Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database (dbSNP147) (National Center for Biotechnology Information, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/); Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC03) (http://exac.broadinstitute.org); ClinVar; Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM); and Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD). Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant (SIFT) (http://sift.jcvi.org/), PolyPhen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), MutationTaster (http://www.mutationtaster.org/), and Protein Variation Effect Analyzer (PROVEAN) (http://provean.jcvi.org/index.php) were used to indicate changes in protein structure and function. PathCards (http://pathcards.genecards.org/) was used to analyze the pathway. CLUSTALW (http://www.genome.jp/tools/clustalw/) was used to analyze the consistency of the amino acid sequences. Candidate pathogenic variants were confirmed using Sanger sequencing.

2.4. Functional Analysis

Bioinformatics analysis suggests that mutation (c.-781C>G) of AHDC1 is located at 5′UTR of AHDC1. Two 1000-bp fragments containing human AHDC1 5′UTR-781C and -781G, respectively, were cloned into a pGL4.10[luc2] vector upstream of luciferase reporter (Promega Benelux BV, Leiden, The Netherlands), and the resultant plasmids (pGL4-C and pGL4-G) were transformed into 293T cells, respectively, to determine effects of the mutation by detecting fluorescence intensity according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as numeral (percentage). Independent Student's t-tests for normal distributions and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for asymmetric distributions were used to analyze the differences in continuous variables. Chi-squared tests were used to analyze categorical variables between OSA and control group. Subsequently, independent Student's t-tests and Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to analyze the differences in continuous variables, and Fisher's exact tests were used to analyze categorical variables between mutation and nonmutation groups. All probability values were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Participants

The present study included 257 patients with OSA and 100 control individuals. Basal characteristics of these individuals are presented in Table 1. No significant differences were observed in age (P=0.055), TC level (P=0.569), or LDL-C level (P=0.400) between OSA and the control group. Compared with the control group, the patients had a higher BMI (27.04 ± 3.36 vs. 23.71 ± 3.09 kg/m2, <0.001), TG level (1.56 ± 1.04 vs. 1.24 ± 0.36 mmol/L, P=0.002), GLU level (3.46 ± 0.95 vs. 3.44 ± 0.62 mmol/L, P=0.002), HDL-C level (1.07 ± 0.23 vs. 1.00 ± 0.18 mmol/L, P=0.018), male proportion (84.82% vs. 70.00%, P=0.002), and prevalence of hypertension (22.96% vs. 13.00%, P=0.035). The OSA group exhibited severe degrees of AHI (32.17 ± 18.06 vs. 3.33 ± 1.14, P < 0.001), significantly lower MSaO2 (93.48 ± 2.28 vs. 95.00 ± 1.37) and LSaO2 (82.14 ± 9.89 vs. 90.00 ± 2.73, P < 0.001) in comparison with the control group.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants.

| Measure | OSA group | Control group | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 257 | 100 | — |

| Age (years) | 58.97 ± 9.41 | 58.11 ± 10.92 | 0.055 |

| Sex (% male) | 84.82 | 70.00 | 0.002∗ |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.04 ± 3.36# | 23.71 ± 3.09 | <0.001∗ |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.13 ± 1.00 | 3.99 ± 1.02 | 0.569 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.56 ± 1.04# | 1.24 ± 0.36 | 0.002∗ |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.07 ± 0.23 | 1.00 ± 0.18 | 0.018∗ |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.47 ± 0.87# | 2.43 ± 0.83 | 0.400 |

| GLU (mmol/L) | 3.46 ± 0.95# | 3.44 ± 0.62 | 0.002∗ |

| Hypertension (%) | 22.96 | 13.00 | 0.035∗ |

| AHI | 32.17 ± 18.06# | 3.33 ± 1.14 | <0.001∗ |

| MSaO2 (%) | 93.48 ± 2.28# | 95.00 ± 1.37 # | 0.002∗ |

| LSaO2 (%) | 82.14 ± 9.89# | 90.00 ± 2.73 | <0.001∗ |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or n (%). Differences between groups were analyzed by the independent Student's t-test, chi-squared test, or Wilcoxon test. #Data were asymmetrically distributed. ∗P < 0.05. BMI: body mass index; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglyceride; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; GLU: fasting blood glucose; AHI: apnea-hypopnea index; MSaO2: mean oxygen saturation; LSaO2: lowest oxygen saturation.

3.2. Identification of Rare Mutations

In order to identify the mutation of AHDC1 in Chinese OSA patients, we sequenced each of 100 moderate-to-severe OSA subjects' DNA samples using targeted sequencing technology. Among the 100 moderate-to-severe OSA patients, in total 57 variants were met the quality filtering criteria, 11 were common polymorphisms (i.e., minor allele frequency of ≥1%), whereas the remaining 46 were rare mutations (minor allele frequency of <1%). To prioritize potential deleterious variants, we focused on the identification of rare mutations (based on the 1000 Genomes, ESP6500, and ExAc databases). Four algorithms (SIFT, PolyPhen-2, MutationTaster, and PROVEAN) were used to predict whether the rare mutations in coding regions would change the protein structure and function. One heterozygous missense mutation (AHDC1: c.G4451A, p.G1484D) (Table 2) was identified in a 58-year-old male with AHI of 23.1, LSaO2 of 85%, and MSaO2 of 92%. We then analyzed mutations in noncoding regions; a mutation (AHDC1: c.-88C>T) in 5′-UTR of AHDC1 was found in a 61-year-old male with AHI of 28.2, LSaO2 of 83%, and MSaO2 of 90%. Another rare variant in 5′-UTR of AHDC1 (c.-781C>G) was identified in a 50-year-old male with AHI of 34.6, LSaO2 of 88%, and MSaO2 of 93% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Probably damaging rare mutations.

| Locus | Gene | Base change | AA change | SIFT | PPT2 | MutationTaster | PRO VEAN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr1:27874176 | AHDC1 | c.G4451A | p.G1484D | D | D | D | N |

| Chr1:27879416 | AHDC1 | c.-88C>T | UTR5 | — | — | — | — |

| Chr1:27879407 | AHDC1 | c.-781C>G | UTR5 | — | — | — | — |

AA: amino acid; SIFT (D: deleterious, T: tolerated); PolyPhen-2 (i.e., PPT2) (D: probably damaging, P: possibly damaging, B: benign); MutationTaster and PROVEAN (D: disease-causing, N: polymorphism).

To identify additional mutation carriers, genotyping was performed in a cohort of 157 moderate-to-severe OSA and 100 control individuals. Among 157 additional patients with OSA, the rare mutation in 5′-UTR of AHDC1 (c.-781C>G) was found in a 61-year-old female with AHI of 68, LSaO2 of 69%, and MSaO2 of 88% (Table 3). In the control group, none of these three mutations was found. In summary, we found three rare mutations in two cohorts (AHDC1: c.G4451A, c.-88C>T, c.-781C>G) (Table 2), and the mutation in 5′-UTR of AHDC1 (c.-781C>G) was found in two patients with OSA (Table 3). All left mutations were confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Supplementary ). The evolutionary conservation of the encoded amino acid residues (AHDC1: c.G4451A) was analyzed in nine different vertebrate species (Supplementary ). The residue that was mutated (AHDC1: c.G4451A) was found to be highly conserved.

Table 3.

Clinical features of patients with rare mutations.

| ID | Age (yr) | Variation | Sex | BMI (kg/m2) | AHI | LSaO2 (%) | MSaO2 (%) | TC (mmol/L) | TG (mmol/L) | HDL-C (mmol/L) | LDL-C (mmol/L) | GLU (mmol/L) | Hypertension | CHD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 58 | p.G1484D | Male | 17.3 | 23.1 | 85.0 | 92.0 | 3.20 | 2.63 | 0.83 | 1.74 | 17.56 | No | Yes |

| 2 | 61 | c.-88C>T | Male | 25.3 | 28.2 | 83.0 | 90.0 | 4.02 | 1.11 | 1.17 | 2.58 | 2.94 | No | No |

| 3 | 50 | c.-781C>G | Male | 23.6 | 34.6 | 88.0 | 93.0 | 3.95 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 2.76 | 4.45 | No | Yes |

| 4 | 61 | c.-781C>G | Female | 34.0 | 68.0 | 69.0 | 88.0 | 2.23 | 2.72 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 12.96 | Yes | Yes |

yr: years; BMI: body mass index; AHI: apnea-hypopnea index; LSaO2: lowest oxygen saturation; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglyceride; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; GLU: fasting blood glucose; CHD: coronary heart disease.

3.3. Clinical Analysis in Patients with or without AHDC1 Mutations

To find whether OSA patients with AHDC1 mutations had different clinical manifestations from the patients without mutations, we analyzed their clinical characteristics. No difference was found between these two groups in age (P=0.628), sex (P=0.578), and BMI (P=0.503) (Supplementary ). So distribution of mutations in AHDC1 is not influenced by age, sex, or BMI in the present study.

Clinical manifestations of OSA patients with AHDC1 mutations are shown in Table 3. Because HDL-C is less affected by drugs, we compared only HDL-C levels for biochemical indicators in patients with mutations. The patient with missense mutation (AHDC1: c.G4451A) was a moderate OSA patient (AHI = 23.1) with lower BMI (BMI = 17.3 kg/m2) and lower HDL-C (0.83 mmol/L), while he was a diabetic and coronary heart disease (CHD) patient. The mutation (c.-88C>T) was found in a fatter male (BMI = 25.3 kg/m2) who was a moderate OSA patient (AHI = 28.2) with normal HDL-C, TG, and fasting blood sugar level. Another mutation in 5′-UTR (c.-781C>G) was found in two severe OSA patients: the first severe OSA patient (AHI = 23.6) was a medium height male (BMI = 23.6 kg/m2) who was younger (50 years) than another three patients, and he was a hypertensive and CHD patient with lower HDL-C (0.84 mmol/L). The other severe OSA patient (AHI = 68,) was a fatter female (BMI = 34 kg/m2) with lower HDL-C (0.83 mmol/L), while she was a diabetic, hypertensive, and CHD patient; this female patient presented lower oxygen saturation (LSaO2 = 69%, MSaO2 = 88%).

3.4. Functional Analysis

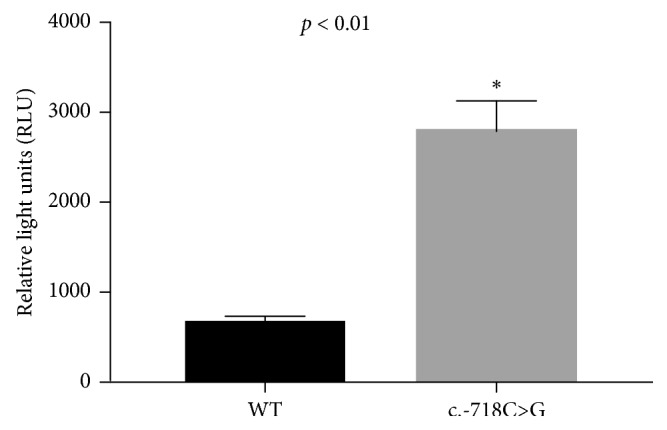

Previous reports have shown that 5′ UTR may influence expression of genes. In this study, two patients with mutation in 5′UTR (c.-781C>G) presented higher AHI and lower oxygen saturation. So, the effect of mutation (c.-781C>G) in 5′UTR of AHDC1 on its expression level was tested. The 293T cells were used for transfection of AHDC1 5′UTR-based reporter constructs (pGL4.10-C, with the C allele or pGL4.10-G, with the G allele). As shown in Figure 2, compared with a negative control, luciferase activity was found to be increased with cotransfection of pGL4.10-G in 293T cells (P < 0.01).

Figure 2.

Luciferase activity. Compared with a negative control, luciferase activity increased with cotransfection of pGL4.10-G in both 293T cells.

4. Discussion

In this study, we identified one rare missense mutation (AHDC1: p.G1484D) and two rare mutations (c.-88C>T and c.-781C>G) in 5′-UTR of AHDC1 in OSA patients. Functional analysis and luciferase reporter assay suggested that the mutation (c.-781C>G) in 5′-UTR played an important role in AHDC1.

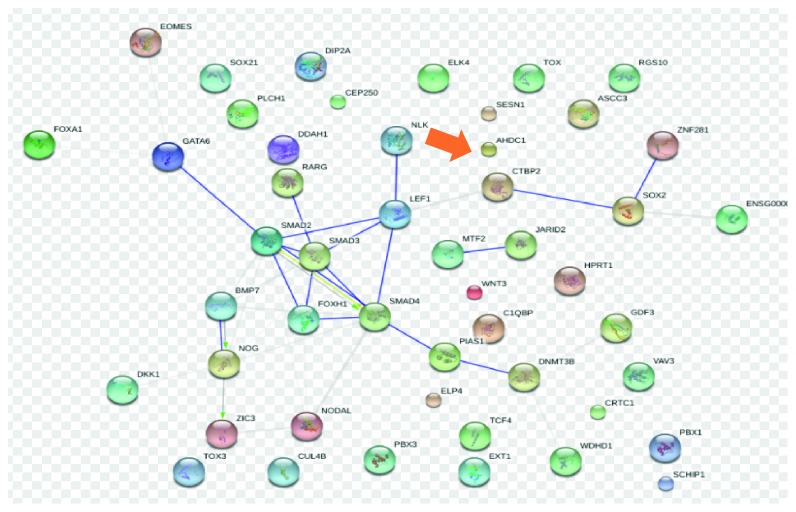

Previous studies have found that the carriers of AHDC1 mutation presented pharyngeal dilator muscle incoordination and oral developmental disorders [26]. In the present study, MalaCards database suggests an important gene associated with sleep apnea is AHDC1, and among its related pathways/superpathways are signaling by GPCR and respiratory electron transport, ATP synthesis by chemiosmotic coupling, and heat production by uncoupling proteins. AHDC1 is also associated with Mesodermal Commitment Pathway (Figure 3) that may influence development of respiratory-related muscles and bones leading to OSA. These evidences suggest that AHDC1 might play an important role in OSA.

Figure 3.

STRING interaction network for Mesodermal Commitment Pathway (SuperPath).

The missense mutation (AHDC1: c.G4451A) was found in a thinner moderate OSA patient. This suggests that OSA may occur in the subject with AHDC1 mutations, even if his or her BMI is small. The mutation in 5′UTR (c.-88C>T) was found in a moderate OSA patient with normal biochemical variables, and he did not take any drugs. This suggests one interesting fact that not all OSA patients might suffer from other diagnosed diseases; every patient has his or her own characteristics, so individualized diagnosis and treatment are necessary. On the other hand, this mutation (c.-88C>T) may not cause changes in pathways related to other diseases, so we have not performed further functional analysis of this mutation. Moreover, another interesting rare mutation in 5′UTR (c.-781C>G) was found in two patients with higher AHI, lower oxygen saturation, and lower HDL-C. Analysis of potential transcriptional binding sites in the proximate promoter region (1-kb of upstream region of the start site of AHDC1) revealed that the c.-781C>G-containing sequence is the binding consensus motif of the transcription factor SREBP-2 (Supplementary ). Mutations of SREBP-2 were found to be related to hypercholesterolemia and perhaps OSA [27]. And luciferase reporter assay suggests the mutation (c.-781C>G) in 5′-UTR of AHDC1 affects expression of gene. All above suggest that AHDC1 may be related to the occurrence of OSA and 5′UTR plays a significant role in AHDC1.

Notably, a recent whole-exome sequencing analysis revealed three different de novo truncating mutations in AHDC1 in four patients with OSA, language delay, and hypotonia [9]. Two missense mutations in AHDC1 were found to be associated with schizophrenia and oral developmental disorders that may lead to upper airway dysfunction and perhaps OSA [20, 21]. Previous founded variants are not only in the coding exon [9] but also in 5′ untranslated region [21]. A de novo balanced translocation with a breakpoint in AHDC1 intron 1 that disrupted the 5′UTR of AHDC1 has been identified in a 5-year-old male patient with developmental delay and intellectual disability [21]. The disruption lead to AHDC1 expression reduced to 50% of wild-type level in lymphoblastoid cells [21]. In the present study, rare mutation (c.-781C>G) in 5′UTR of AHDC1 was found in severe OSA patients, and this rare mutation could affect expression of AHDC1. Therefore, we assumed that the mutations in AHDC1 may affect the expression of AHDC1 and lead to sleep apnea. The exact mechanism of this phenomenon needs to be investigated.

This study has some limitations. The participants may not be entirely representative of the general Han Chinese population. Potential false-positive results may still be possible. Prospective cohort studies are needed to confirm the variants in our study. We sequenced limited genes and limited sequencing regions that were most likely to harbor functional variation. Some of the patients and controls with CHD were taking drugs. The results of TC, LDL-C, and TG comparison between two groups may be different from those of other studies. Finally, the exact mechanism of these variants is not fully understood and requires further functional studies.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we identified multiple novel variants of AHDC1 in patients with OSA. Our findings increase the mutation spectrum of associated genes for OSA, a quite complex disease. Gene analysis is helpful for individualized typing of patients with OSA and might contribute to personalized diagnosis and treatment in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants in this study. They also thank Shuai Chen and Kun Wang for their help during the data analysis. Finally, they thank Angela Morben, DVM, ELS, from Liwen Bianji, Edanz Group China (http://www.liwenbianji.cn/ac), for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant nos. 81670331 and 81870335); Beijing Billion Talent Project (2017-A-10); the Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Clinical Medicine Development of Special Funding Support (ZYLX201605); the Beijing Key Laboratory of Upper Airway Dysfunction and Related Cardiovascular Diseases (No. BZ0377); and the International Science and Technology Cooperation Program of China (2015DFA30160). The research funds were used to design the study, prepare human samples, and purchase sequencing kits.

Contributor Information

Yong-Xiang Wei, Email: weiyxanzhen@163.com.

Yan-Wen Qin, Email: qinyanwen@vip.126.com.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. No identifying information about participants is available in this article.

Disclosure

Song Yang and Kun Li are co-first authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: detailed information of targeted sequencing panel. Supplementary Table 2: AmpliSeqT amplicons and coverage details of obstructive sleep apnea-targeted sequencing assay. Supplementary Table 3: primers of panel. Supplementary Table 4: characteristics between mutation and nonmutation groups. Supplementary Figure 1: Sanger sequencing chromatograms of variants in AHDC1. Supplementary Figure 2: analysis of potential transcriptional binding sites in the proximate promoter region. Supplementary Figure 3: analysis of sequence conservation in nine species of missense mutation identified in AHDC1.

References

- 1.Cade B. E., Chen H., Stilp A. M., et al. Genetic associations with obstructive sleep apnea traits in Hispanic/Latino Americans. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2016;194(7):886–897. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201512-2431oc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peppard P. E., Young T., Barnet J. H., Palta M., Hagen E. W., Hla K. M. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2013;177(9):1006–1014. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strohl K. P., Saunders N. A., Feldman N. T., Hallett M. Obstructive sleep apnea in family members. New England Journal of Medicine. 1978;299(18):969–973. doi: 10.1056/nejm197811022991801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmer L. J., Buxbaum S. G., Larkin E., et al. A whole-genome scan for obstructive sleep apnea and obesity. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2003;72(2):340–350. doi: 10.1086/346064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kripke D. F., Kline L. E., Nievergelt C. M., et al. Genetic variants associated with sleep disorders. Sleep Medicine. 2015;16(2):217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varvarigou V., Dahabreh I. J., Malhotra A., Kales S. N. A review of genetic association studies of obstructive sleep apnea: field synopsis and meta-analysis. Sleep. 2011;34(11):1461–1468. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon C. T., Vuillot A., Marlin S., et al. Heterogeneity of mutational mechanisms and modes of inheritance in auriculocondylar syndrome. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2013;50(3):174–186. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marca G. D., Vasta I., Scarano E., et al. Obstructive sleep apnea in Costello syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2006;140A(3):257–262. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xia F., Bainbridge M. N., Tan T. Y., et al. De novo truncating mutations in AHDC1 in individuals with syndromic expressive language delay, hypotonia, and sleep apnea. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2014;94(5):784–789. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mo L., He Q., Wang Y., Dong B., He J. High prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in Marfan’s syndrome. Chinese Medical Journal. 2014;127(17):3150–3155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palmer L. J., Buxbaum S. G., Larkin E. K., et al. Whole genome scan for obstructive sleep apnea and obesity in African-American families. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2004;169(12):1314–1321. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200304-493oc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carmelli D., Colrain I. M., Swan G. E., Bliwise D. L. Genetic and environmental influences in sleep-disordered breathing in older male twins. Sleep. 2004;27(5):917–922. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.5.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang D., Xiao Y., Luo J. Genetics of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Chinese Medical Journal. 2014;127(17):3135–3141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Redline S., Tishler P. V., Tosteson T. D., et al. The familial aggregation of obstructive sleep apnea. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1995;151(3):682–687. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/151.3_pt_1.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campana L., Eckert D. J., Patel S. R., Malhotra A. Pathophysiology & genetics of obstructive sleep apnoea. The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2010;131:176–187. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jordan A. S., McSharry D. G., Malhotra A. Adult obstructive sleep apnoea. The Lancet. 2014;383(9918):736–747. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60734-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Redline S., Tishler P. V. The genetics of sleep apnea. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2000;4(6):583–602. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2000.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim J., Hao T., Shaw C., et al. A protein-protein interaction network for human inherited ataxias and disorders of Purkinje cell degeneration. Cell. 2006;125(4):801–814. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dang D., Cunnington D. Excessive daytime somnolence in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2010;290(1-2):146–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guipponi M., Santoni F. A., Setola V., et al. Exome sequencing in 53 sporadic cases of schizophrenia identifies 18 putative candidate genes. PLoS One. 2014;9(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112745.e112745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quintero-Rivera F., Xi Q. J., Keppler-Noreuil K. M., et al. MATR3 disruption in human and mouse associated with bicuspid aortic valve, aortic coarctation and patent ductus arteriosus. Human Molecular Genetics. 2015;24(8):2375–2389. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mardis E. R. The impact of next-generation sequencing technology on genetics. Trends in Genetics. 2008;24(3):133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berry R. B., Budhiraja R., Gottlieb D. J., et al. Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: update of the 2007 AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events. Deliberations of the sleep apnea definitions task force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2012;8(5):597–619. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foster G. D., Borradaile K. E., Sanders M. H., et al. A randomized study on the effect of weight loss on obstructive sleep apnea among obese patients with type 2 diabetes: the Sleep AHEAD study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009;169(17):1619–1626. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheung Y. Y., Tai B. C., Loo G., et al. Screening for obstructive sleep apnea in the assessment of coronary risk. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2017;119(7):996–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Javaheri S., Barbe F., Campos-Rodriguez F., et al. Sleep apnea: types, mechanisms, and clinical cardiovascular consequences. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2017;69(7):841–858. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J., Grigoryev D. N., Ye S. Q., et al. Chronic intermittent hypoxia upregulates genes of lipid biosynthesis in obese mice. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2005;99(5):1643–1648. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00522.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: detailed information of targeted sequencing panel. Supplementary Table 2: AmpliSeqT amplicons and coverage details of obstructive sleep apnea-targeted sequencing assay. Supplementary Table 3: primers of panel. Supplementary Table 4: characteristics between mutation and nonmutation groups. Supplementary Figure 1: Sanger sequencing chromatograms of variants in AHDC1. Supplementary Figure 2: analysis of potential transcriptional binding sites in the proximate promoter region. Supplementary Figure 3: analysis of sequence conservation in nine species of missense mutation identified in AHDC1.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.