Abstract

Introduction:

Latino communities are disproportionately affected by type 2 diabetes and experience disparities in access to diabetes prevention programs. The purpose of this study was to test the preliminary efficacy of a culturally grounded, diabetes prevention program for high-risk Latino families delivered through an integrated research–practice partnership.

Study design:

The integrated research–practice partnership was established in a predominantly Latino community and consisted of a Federally Qualified Health Center, a YMCA, an accredited diabetes education program, and an academic research center. Data were collected and analyzed from 2015 to 2018.

Setting/participants:

Latino families consisting of a parent with an obese child between age 8 and 12 years.

Intervention:

The 12-week lifestyle intervention included nutrition education and behavioral skills training (60 minutes, once/week) and physical activity classes (60 minutes, three times/week) delivered at a YMCA.

Main outcome measures:

Outcomes included measures of adiposity (BMI, waist circumference, and body fat); HbA1c; and weight-specific quality of life.

Results:

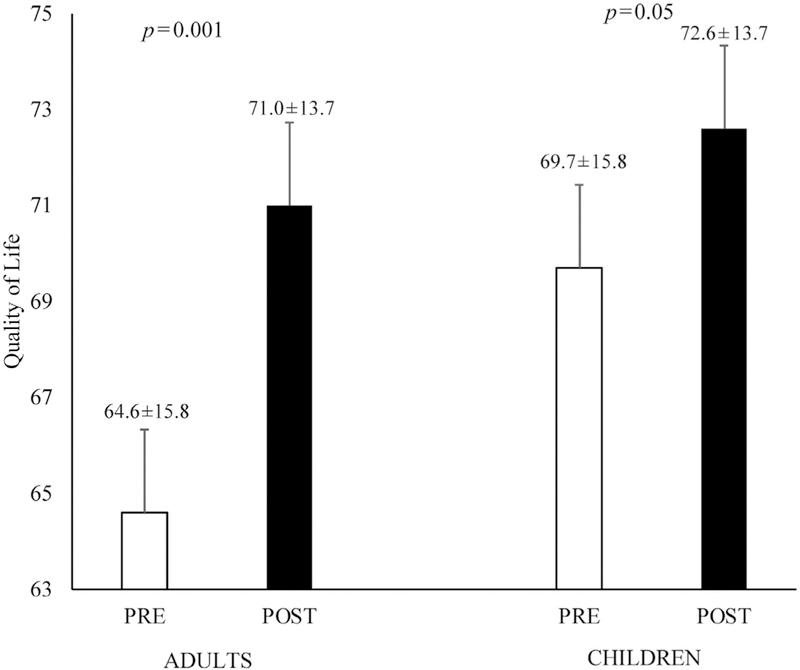

Over the course of the 2-year project period, 58 families (parents n=59, children n=68) were enrolled with 36% of parents and 29% of children meeting the criteria for prediabetes at baseline. Feasibility and acceptability were high, with 83% of enrolled families completing the program, 91% of the intervention sessions attended, and 100% of families stating they would recommend the program. The intervention led to significant decreases in percentage body fat among parents (46.4% [SD=10.8] to 43.5% [SD=10.5], p=0.001) as well as children (43.1% [SD=8.0] to 41.8% [SD=7.2], p=0.03). Additionally, HbA1c was significantly reduced in parents (5.6% [SD=0.4] to 5.5% [SD=0.3], p=0.03), and remained stable in children (5.5% [SD=0.3] vs 5.5% [SD=0.3], p>0.05). Significant improvements in quality of life were reported in parents (64.6 [SD=15.8] to 71.0 [SD=13.7],p=0.001) and children (69.7 [SD=15.8] to 72.6 [SD=13.7],p=0.05).

Conclusions:

These findings support the preliminary efficacy of an integrated research–practice partnership to meet the diabetes prevention needs of high-risk Latino families within a vulnerable community.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity disproportionately affects Latino communities, contributing to increased risk for type 2 diabetes (T2D).1,2 Disparities in T2D emerge early in life, where Latino youth exhibit higher rates of prediabetes compared with non-Hispanic whites and up to 50% of Latino children are projected to develop T2D in their lifetime.2,3 The prevalence of T2D in Latino adults is double compared with non-Hispanic whites (22.6% vs 11.3%) and the incidence of undiagnosed T2D is increasing in Latinos.4 Given that Latinos are the largest minority group in the U.S. and Latino families experience a disproportionate T2D burden, there is a critical need for family-based diabetes prevention programs in Latino communities.

Although diabetes may be best managed in a medical home, the current healthcare system is not optimized to address contextual factors essential for preventing diabetes particularly in low-income communities that lack access to health promotion resources.5 Integrated research–practice partnerships (IRPPs) represent a collaborative approach where community stakeholders, healthcare settings, and researchers come together to integrate evidence-based programs into practice-based settings.6,7 The most effective obesity prevention programs for minority youth address contextual factors that influence health and health behaviors. These factors may include relationships with family and friends, opportunities and challenges within the community, cultural beliefs, and access to health promotion services.8,9 However, few studies have used family-based, culturally grounded intervention strategies to prevent diabetes in Latino families living in disadvantaged communities.10 Therefore, the purpose of this study is to test the preliminary efficacy of a culturally grounded, diabetes prevention program for high-risk Latino families delivered through an IRPP.

METHODS

Study Sample

Maryvale is a predominantly Latino (76%) community in Phoenix, Arizona, with a high level of neighborhood disadvantage. Approximately 50% of households are single-parent, 50% of the population has not graduated high school, and 70% live below the federal poverty line. A 2016 survey reported that almost 50% of children and adolescents in Maryvale were overweight or obese and 9% of adults have T2D.11,12 Maryvale is a federally designated Medically Underserved Area and Health Professional Shortage Area indicating a shortage of primary care providers and health services.

The IRPP originated from a previously conducted research study that tested the efficacy of a culturally grounded diabetes prevention intervention for obese Latino adolescents.13 The intervention was conceptualized by bilingual/bicultural community dietitians through an inductive process that was grounded in the diabetes prevention needs of the local Latino community.14 Latino cultural values of familismo (familism), confianza (trust), and respeto (respect) are leveraged and the program is implemented with a collectivistic orientation where families come together within family-friendly community settings to support each other. The cultural grounding and testing of the intervention are described elsewhere.13–16 Several observations led to the need for an IRPP in Maryvale and included the following: (1) 50% of previous participants resided in Maryvale; (2) 15% of adolescents were prediabetic at enrollment; and (3) six adolescents were found to have T2D and required a referral for medical management. From these observations, the need for prevention efforts earlier in the life course (i.e., pre-adolescents) was evident and the inclusion of parents as participants would enhance engagement. Embedding the program in a medical home within the Maryvale community would facilitate recruitment as well as ensure that medical management could be provided if needed.

The research team approached two Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) in Maryvale but only one, the Maryvale branch of Mountain Park Health Center (MPHC), provided care to children and adults within the same facility. MPHC expressed a strong interest in the IRPP and demonstrated key attributes underpinning IRPP success including willingness to modify existing practices and buy-in from staff that ranged from promotoras (community health workers) to behavioral health providers and physicians.17,18 Additional IRPP institutions included an academic research center, an American Association of Diabetes Educators–accredited diabetes education program consisting of registered dietitians and health educators, and the Maryvale Family YMCA (executive director, administrative staff, and fitness instructors). A framework was outlined to engage MPHC providers and staff, a research coordinator was embedded within MPHC, the research study was added to provider meeting agendas, and the electronic medical record (EMR) was modified to facilitate recruitment and communication. In addition, a Business Associates Agreement was secured to allow for the sharing of protected health information.

Measures

Potentially eligible youth with scheduled clinic appointments were flagged within the EMR and families were approached by promotoras to introduce the program. Families that expressed interest were referred to the research coordinator and screened for the following inclusion criteria: (1) Latino, (2) age 8–12 years, (3) obesity (BMI percentile ≥95th for age and sex), (4) non-diabetic, and (5) not taking medications or diagnosed with a condition that influences metabolism or health behaviors. Parents were required to be patients at MPHC and were screened to determine their willingness and availability to attend the 12-week program. In the event that a parent was not an MPHC patient, a system was developed to establish the parent as a patient, requiring them to see a primary care provider prior to enrollment. The Arizona State University IRB approved the study and written informed consent and assent were obtained prior to any procedures.

Families that met eligibility were scheduled for an in-person visit with the research coordinator who administered consent. Following consent, providers at MPHC were notified through the EMR that their patient enrolled so that labs could be ordered. Following baseline assessments (described below), families were invited to orientation at the YMCA where the lifestyle intervention would be delivered. A 6-week progress report and 12-week final report were uploaded to the participant’s EMR to inform their provider of their attendance, behavioral goals, and progress throughout the program. Upon completion of the intervention, families returned to MPHC for a follow-up lab draw and provider visit to discuss changes in health outcomes and behaviors and develop a plan for future care. The purpose of the follow-up visit was to improve access to care and strengthen ties between families and providers. Families who attended 80% of intervention sessions received an extended YMCA membership (12 months). Partnering institutions met monthly to discuss progress and address any challenges. Members of the research team also attended monthly MPHC provider meetings to discuss recruitment, provide updates, and present outcomes.

The 12-week intervention was guided by Social Cognitive Theory to support changes in nutrition-related behaviors (e.g., decreased fat and sugar intake and increased fruit and vegetable intake) by enhancing self-efficacy, teaching goal setting, and facilitating social support.19 The curriculum also focused on emotional wellbeing by addressing topics, such as self-esteem, family communication, roles, and responsibilities.13 Bilingual/bicultural registered dietitians and community health educators delivered nutrition education sessions (60 minutes, once/week) to groups of families. Parents and youth were separated during some nutrition sessions in order to deliver age-appropriate content but came together to work on family goals and discuss roles and responsibilities within the context of family. YMCA fitness instructors led exercise sessions (60 minutes, three times/week) with two exercise sessions for children and a third for the entire family. Participants were incentivized with gift cards (up to a total of $25) for attendance, completing out-of-class activities, and making progress toward goals.

Feasibility was evaluated by the IRPP’s ability to work collaboratively, develop a system for identifying and enrolling families, and implementing the program across institutions. Acceptability was measured by attendance and families’ willingness to refer a family member or friend to the program. Preliminary efficacy was determined by changes in adiposity and diabetes risk. Weight, height, and waist circumference were measured to the nearest 0.1 kg and 0.1 cm, respectively, and used to calculate BMI and BMI percentile/z-score in children. Body composition was determined using bioelectrical impedance analysis. T2D risk was assessed from a fasting blood sample to determine HbA1c (photometric analysis).

Physical activity (PA) in adults was assessed using the Rapid Assessment of PA.20 This nine-item questionnaire assesses leisure-time PA on a scale of 1 (being inactive) to 7 (highly active). Moderate to vigorous PA in children was assessed using a wrist-worn GENEActiv triaxial accelerometer for 7 days. At least 4 days with ≥10 hours of wear time was considered valid for analyses using R-package GGIR, version 1.2, in 1-minute epochs.21,22 Dietary behaviors were assessed in adults using the Brief Dietary Assessment Tool for Hispanics and the 2007 Block Food Screener in children.23

Obesity and weight-loss quality of life (QOL) was measured in parents using a 21-item instrument that captures weight-related QOL across three domains, self, social, and environment.24 Obesity and health-related QOL was measured in youth using the Sizing Me Up© survey across domains of emotional, physical, social avoidance, positive social attributes, and teasing/marginalization.25,26 For parents and children, scores across each domain were summed for a total score ranging from 0 to 100 where higher scores indicate higher QOL.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive characteristics are presented as means and SDs. Paired sample t-tests were used to examine changes in diet, PA, weight, BMI/BMI%/BMI z-score, waist circumference, percentage of fat, HbA1c, and QOL. Data were collected between 2015 and 2018 and analyzed using SPSS, version 23 with significance set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Of the 126 families referred by MPHC, 77 met eligibility criteria and 58 were enrolled (Appendix Figure 1, available online). Thirty-five parents (60%) were not MPHC patients and needed to establish care prior to enrollment. Most families came from low-socioeconomic back-grounds, with 30% being employed, 40% on two or more government assistance programs, and 69% reported a monthly household income of $1,000–$2,000. Table 1 presents baseline characteristics of families where the majority of parents were mothers, but children were evenly distributed by sex. A third of parents and children were prediabetic (HbA1c ≥5.7%) at baseline and 6% of parents were diabetic (HbA1c ≥6.5%). Adults with T2D were referred to their provider for care and allowed to participate if medically cleared. Forty-eight of the original 58 families (≅83%) completed the 12-week intervention. Nutrition and fitness instructors recorded attendance at every session and families attended 91% of all sessions during the 12-week program. Post-intervention surveys demonstrated a high degree of acceptability, with 100% of the families reporting they would recommend the program to a family member or friend.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Enrolled Participants

| Characteristics | Adults (n=59) |

Children (n=68) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, M±SD | 37.3±6.5 | 9.8±1.3 |

| Gender, % | ||

| Male | 7.8 | 42.9 |

| Female | 92.2 | 57.1 |

| Prediabetic, % | 36 | 29 |

| Diabetic, % | 6 | 0 |

Changes in lifestyle behaviors for adults and children are presented in Table 2. Adults reported significant decreases in fat intake (–5.3 g/day, p=0.004) but no changes in fruit and vegetable intake or PA (p values >0.05). In children, the only significant change was a decrease in fruit and vegetable intake (–0.5 servings, p=0.03). Changes in adiposity and diabetes risk are presented in Table 3. Parents exhibited significant reductions in waist circumference (–3.3 cm, p=0.001); percentage body fat (–2.9%, p=0.001); and HbAlc (0.1%, p=0.03). Children exhibited significant decreases in BMI percentile (–0.6%, p<0.001), BMI z-score (–0.16, p<0.001), as well as reductions in waist circumference (–2.5 cm, p=0.001) and percentage body fat (–1.3%, p=0.001). Despite reductions in measures of adiposity, children did not exhibit any changes in HbA1c. Changes in obesity- and weight-specific QOL are presented in Figure 1 and indicate that both adults (6.4, p=0.001) and children (2.9, p=0.05) reported significant increases in QOL following the intervention.

Table 2.

Changes in Lifestyle Behaviors

| Adults (n=43) |

Children (n=47) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Baseline, M±SD |

Post, M±SD |

p-value | Baseline, M±SD |

Post, M±SD |

p-value |

| Fat intake (g/day) | 21.1±10.6 | 15.8±8.0 | 0.004** | 28.8±14.8 | 32.9±29.1 | 0.593 |

| FV intake (servings/day) | 2.4±1.3 | 2.8±1.4 | 0.233 | 1.6±0.9 | 1.1±0.8 | 0.034* |

| Physical activity (RAPA score/minutes/day) | 3.4±1.6 | 3.6±1.4 | 0.342 | 44.1±34.0 | 44.3±36.5 | 0.953 |

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01).

FV, fruit and vegetable; RAPA, Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity (range 1=being inactive to 7=highly active).

Table 3.

Changes in Adiposity and Diabetes Risk

| Adults (n=43) |

Children (n=47) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Baseline, M±SD |

Post, M±SD |

p-value | Baseline, M±SD |

Post, M±SD |

p-value |

| Weight (kg) | 82.1±17.8 | 80.6±17.8 | 0.118 | 62.93±17.3 | 63.8±17.6 | 0.029* |

| BMI/BMI % | 32.1±5.9 | 31.6±6.0 | 0.121 | 98.2±1.3 | 97.6±1.6 | <0.001** |

| BMI z-score | — | — | — | 2.2±0.3 | 2.04 ±0.3 | <0.001** |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 98.8±13.4 | 95.5±14.1 | 0.001** | 90.8±11.1 | 88.3±11.1 | 0.001** |

| Total fat (%) | 46.4±10.8 | 43.5±10.5 | 0.001** | 43.1±8.0 | 41.8±7.2 | 0.034* |

| Fat mass (kg) | 38.8±15.7 | 36.4±15.0 | 0.025* | 27.4±11.5 | 27.1±11.7 | 0.523 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.6±0.4 | 5.5±0.3 | 0.030* | 5.5±0.03 | 5.5±0.3 | 0.775 |

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01).

Figure 1.

Changes in weight-specific quality of life in adults and children.

DISCUSSION

The complexity of T2D-related disparities in Latino families requires multidisciplinary, collaborative approaches.27–29 This study tested the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of ¡Viva Maryvale!, a culturally grounded diabetes prevention program for high-risk Latino families. In addition to supporting feasibility and acceptability, the intervention resulted in significant reductions in adiposity and HbA1c in adults, and reductions in adiposity outcomes in children. Further, both children and adults reported significant increases in obesity-related QOL. These encouraging findings coupled with high attendance and retention rates support the utility of an IRPP to address the diabetes prevention needs of high-risk Latino families from a vulnerable and underserved community.

The Diabetes Prevention Program demonstrated that intensive lifestyle intervention with 7% weight loss can significantly prevent or delay T2D in high-risk adults.30 The Diabetes Prevention Program has been successfully translated to community settings to yield 3%–5% weight loss sustained over 12 months of follow-up.31 Adults enrolled in ¡Viva Maryvale! exhibited a 1.8% reduction in weight after 3 months of intervention (effect size=0.2) with a 0.1% reduction in HbA1c (effect size=0.4). Given the short intervention period, it is difficult to know the clinical significance of these results in relation to long-term diabetes prevention. However, the fact that the observed weight loss was coupled with a significant, albeit small, reduction in HbA1c is promising as HbA1c is an established predictor of future diabetes risk.32 Although less is known about weight loss and future health in children, a recent U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation used a BMI z-score reduction of 0.20 as a suitable threshold for clinically meaningful changes.33 Therefore, it is likely that longer intervention and follow-up periods will be necessary to understand the true clinical significance of the observed 0.16 reduction in BMI z-score (effect size=0.5). Nonetheless, positively impacting the health trajectory of high-risk children and adults identified within a clinical practice may represent an important step towards clinically meaningful diabetes prevention.

Many of the children enrolled met the classification for severe obesity, which is a subset of obesity that disproportionately impacts minority children34 and contributes to an increased risk of T2D.35 Moreover, pediatric severe obesity is associated with cardiovascular deconditioning,36 so the PA component of the program was designed to improve exercise tolerance. Despite high attendance for the program, youth did not increase PA after participation, suggesting that severely obese children from disadvantaged neighborhoods may face additional barriers for engaging in and maintaining PA outside of formalized programs.

Implementing culturally adapted evidence-based interventions in real-world settings is a promising strategy for addressing health disparities.37 Although the Diabetes Prevention Program has been adapted for Latino populations in community settings,38,39 these adaptations have largely involved language translation rather than deep-structure cultural adaptations to engage high-risk Latino families.38-41 ¡Viva Maryvale! included elements from the Diabetes Prevention Program, such as goal setting and self-monitoring, but was culturally grounded and also integrated additional behavior change components to engage families, such as role modeling from parents and health educators, and fostering social support among families within a single community.13,42 This bottom-up approach to grounding an evidence-based intervention to integrate the best available science with the sociocultural context of the population to facilitate engagement, retention, and efficacy holds potential for long-term sustainability.27,37,43

Translation to the community setting was achieved through the IRPP by developing a shared mission and vision, shared decision making, allocating adequate resources, and bidirectional knowledge exchange.44 Ongoing engagement of partners throughout the planning and implementation phases allowed the program to be embedded within existing infrastructure and services at the YMCA and MPHC. For example, the YMCA began providing family-based exercise classes and allowing outside health educators to deliver nutrition education. MPHC allowed a research coordinator to be embedded in the clinic to leverage the EMR for research purposes. Embedding the program within partnering institutions’ existing infrastructure can enhance feasibility and effectiveness and may support future macro-level policy changes.45,46 Lastly, the IRPP fostered co-learning and capacity building at the individual and organizational levels, increasing the collective ability to engage in diabetes prevention activities.46

Future directions for ¡Viva Maryvale! will focus on the dissemination and implementation within the FQHC setting. Given that 50% of youth in this predominantly Latino community are overweight or obese and a third of participants presented with prediabetes, there is an urgent need to expand the reach of this program through the medical home. However, the translation of evidence to practice is often the least understood stage in prevention research.42 There is a critical need to rigorously evaluate the uptake of programming in clinical settings to understand the processes by which a prevention intervention fits within the clinical setting and the processes by which a medical home engages in integrated, collaborative partnerships to address complex health issues.37,47 All FQHCs operate with a guiding mission to provide comprehensive, culturally competent primary care and preventive services to underserved populations. FQHCs often use an integrated care model to serve families within the same facility; thus, they are well positioned to implement family-based prevention programming.48 IRPPs can facilitate the translation of evidence-based interventions into clinical settings as they engage providers and researchers, ensuring that a particular intervention fits within the resources, mission, and priorities of the clinic.49 FQHCs are required by law to have an advisory board composed of providers and clinic users.50 Leveraging the board to integrate research provides a natural avenue for establishing IRPPs within FQHCs. Adapting interventions to address vulnerable subgroups at highest risk for T2D through similar settings will inform the development of culturally and contextually adapted diabetes prevention models in other communities.37

Limitations

The strengths of this study include the focus on high-risk families in an underserved community, a culturally grounded intervention, and an inter-institutional community collaboration. Despite these strengths, this study is not without limitations. To start, this pilot included a relatively small sample of families. Further, there was no long-term follow-up assessment limiting the ability to assess the impact and sustainability of the intervention. From an implementation perspective, the degree to which providers discussed the program with their patients was not assessed. This study focused exclusively on Latino families in Maryvale, which limits the generalizability for other high-risk communities or racial/ethnic subgroups. Another limitation is the lack of a control group limiting the ability to make definitive conclusions regarding the effectiveness of the intervention. RCTs lead to extremely important advances in science; however, findings from RCTs do not always translate to real-world settings. In order to reach vulnerable communities, there is a need to implement and test innovative community-based approaches in settings and populations that may not be suited for RCTs.51 Furthermore, many community stakeholders feel that it is unethical to randomize participants to a control group when the needs are high, resources are limited, and the potential for direct benefits are likely.51

CONCLUSIONS

These results suggest that culturally grounded diabetes prevention programming delivered through an IRPP is a promising approach for identifying and engaging high-risk Latino families in a vulnerable community. Rigorous testing of this approach is warranted to define the processes for successful dissemination and implementation with the goal of establishing generalizable diabetes prevention models to address T2D disparities across vulnerable communities.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was made possible through funding from the Arizona Department of Health Services though contract ADHS16–105121 to Arizona State University. Drs. Soltero and Shaibi were supported by a grant from NIH, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (R01DK10757901). We are grateful for the contributions of Dr. Ugonna Woods, MD; and the Departments of Pediatrics, Family Medicine, and Integrated Behavioral Health at Mountain Park Health Center. We thank Matt Sandoval, Yolanda Konopken, Anna Alonzo, and Dr. Colleen Keller for their contributions in developing ¡Viva Maryvale! and are indebted to Marta Ormeno for her help in recruiting and enrolling families.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental materials associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.07.034.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among U.S. children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):483–490. 10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pettitt DJ, Talton J, Dabelea D, et al. Prevalence of diabetes in U.S. youth in 2009: the SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(2):402–408. 10.2337/dc13-1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narayan KM, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Sorensen SW, Williamson DF. Lifetime risk for diabetes mellitus in the United States. JAMA. 2003;290(14):1884–1890. 10.1001/jama.290.14.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menke A, Casagrande S, Geiss L, Cowie CC. Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among adults in the United States, 1988–2012. JAMA. 2015;314(10):1021–1029. 10.1001/jama.2015.10029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sampselle CM. Nickel-and-dimed in America: underserved, under-studied, and underestimated. Fam Community Health. 2007;30 (suppl 1):S4–S14. 10.1097/00003727-200701001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Everette A, Brooks A, Ramalingam NS, et al. An integrated research-practice partnership for physical activity promotion in a statewide program. Transl J Am Coll Sports Med 2017;2(11):57–67. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson ML, Strayer TE, Davis R, Harden SM. Use of an integrated research-practice partnership to improve outcomes of a community-based strength-training program for older adults: reach and effect of Lifelong Improvements through Fitness Together (LIFT). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(2). 10.3390/ijerph15020237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill JO, Galloway JM, Goley A, et al. Scientific statement: socioecological determinants of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(8):2430–2439. 10.2337/dc13-1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seo DC, Sa J. A meta-analysis of obesity interventions among U.S. minority children. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(4):309–323. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gicevic S, Aftosmes-Tobio A, Manganello JA, et al. Parenting and childhood obesity research: a quantitative content analysis of published research 2009–2015. Obes Rev 2016;17(8):724–734. 10.1111/obr.12416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arizona Department of Health Services. Maryvale Village Primary Care Area, Statistical Profile-2016. Published 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Diabetes data and statistics, county data. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/atlas/countydata/atlas.html. Published 2013. Accessed January 25, 2018.

- 13.Williams AN, Konopken YP, Keller CS, et al. Culturally-grounded diabetes prevention program for obese Latino youth: rationale, design, and methods. Contemp Clin Trials. 2017;54:68–76. 10.1016/j.cct.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaibi GQ, Greenwood-Ericksen MB, Chapman CR, Konopken Y, Ertl J. Development, implementation, and effects of community-based diabetes prevention program for obese Latino youth. J Prim Care Community Health. 2010;1(3):206–212. 10.1177/2150131910377909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaibi GQ, Konopken YP, Nagle-Williams A, McClain DD, Castro FG, Keller CS. Diabetes prevention for Latino youth: unraveling the intervention “black box.” Health Promot Pract 2015;16(6):916–924. 10.1177/1524839915603363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaibi GQ, Konopken Y, Hoppin E, Keller CS, Ortega R, Castro FG. Effects of a culturally grounded community-based diabetes prevention program for obese Latino adolescents. Diabetes Educ 2012;38(4):504–512. 10.1177/0145721712446635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castaneda SF, Holscher J, Mumman MK, et al. Dimensions of community and organizational readiness for change. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2012;6(2):219–226. 10.1353/cpr.2012.0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ober AJ, Watkins KE, Hunter SB, et al. Assessing and improving organizational readiness to implement substance use disorder treatment in primary care: findings from the SUMMIT study. BMC Fam Pract 2017;18(1):107 10.1186/s12875-017-0673-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav 2004;31(2):143–164. 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Topolski TD, LoGerfo J, Patrick DL, Williams B, Walwick J, Patrick MB. The Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity (RAPA) among older adults. Prev Chronic Dis 2006;3(4):A118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rowlands AV, Yates T, Davies M, Khunti K, Edwardson CL. Raw accelerometer data analysis with GGIR R-package: does accelerometer brand matter? Med Sci Sports Exerc 2016;48(10):1935–1941. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ward DS, Evenson KR, Vaughn A, Rodgers AB, Troiano RP. Accelerometer use in physical activity: best practices and research recommendations. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2005;37(suppl 11):S582–S588. 10.1249/01.mss.0000185292.71933.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wakimoto P, Block G, Mandel S, Medina N. Development and reliability of brief dietary assessment tools for Hispanics. Prev Chronic Dis 2006;3(3):A95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patrick DL, Bushnell DM, Rothman M. Performance of two self-report measures for evaluating obesity and weight loss. Obes Res 2004;12 (1):48–57. 10.1038/oby.2004.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeller MH, Modi AC. Predictors of health-related quality of life in obese youth. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14(1):122–130. 10.1038/oby.2006.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeller MH, Modi AC. Development and initial validation of an obesity-specific quality-of-life measure for children: sizing me up. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17(6):1171–1177. 10.1038/oby.2009.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Economos CD, Hammond RA. Designing effective and sustainable multifaceted interventions for obesity prevention and healthy communities. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25(7):1155–1156. 10.1002/oby.21893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hatfield DP, Sliwa SA, Folta SC, Economos CD, Goldberg JP. The critical role of communications in a multilevel obesity-prevention intervention: lessons learned for alcohol educators. Patient Educ Couns 2017;100(suppl 1):S3–S10. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sliwa S, Goldberg JP, Clark V, et al. Using the Community Readiness Model to select communities for a community-wide obesity prevention intervention. Prev ChronicDis 2011;8(6):A150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002;346(6):393–403. 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ali MK, Echouffo-Tcheugui J, Williamson DF. How effective were life-style interventions in real-world settings that were modeled on the Diabetes Prevention Program? Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(1):67–75. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edelman D, Olsen MK, Dudley TK, Harris AC, Oddone EZ. Utility of hemoglobin A1c in predicting diabetes risk. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19(12):1175–1180. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, Grossman DC, Bibbins-Domingo K, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for obesity in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;317(23):2417–2426. 10.1001/jama.2017.6803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skinner AC, Ravanbakht SN, Skelton JA, Perrin EM, Armstrong SC. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity in U.S. children, 1999–2016. Pediatrics. 2018;141(3):e20173459. 10.1542/peds.2017-3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanamas SK, Reddy SP, Chambers MA, et al. Effect of severe obesity in childhood and adolescence on risk of type 2 diabetes in youth and early adulthood in an American Indian population. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018;19(4):622–629. 10.1111/pedi.12627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gidding SS, Nehgme R, Heise C, Muscar C, Linton A, Hassink S. Severe obesity associated with cardiovascular deconditioning, high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, diabetes mellitus/hyperinsulinemia, and respiratory compromise. J Pediatr 2004;144(6):766–769. 10.1016/S0022-3476(04)00243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Castro FG, Yasui M. Advances in EBI development for diverse populations: towards a science of intervention adaptation. Prev Sci 2017;18 (6):623–629. 10.1007/s11121-017-0809-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hall DL, Lattie EG, McCalla JR, Saab PG. Translation of the Diabetes Prevention Program to ethnic communities in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016; 18(2):479–489. 10.1007/s10903-015-0209-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tabak RG, Sinclair KA, Baumann AA, et al. A review of diabetes prevention program translations: use of cultural adaptation and implementation research. Transl Behav Med 2015;5(4):401–414. 10.1007/s13142-015-0341-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jackson L. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program into practice: a review of community interventions. Diabetes Educ 2009;35(2):309–320. 10.1177/0145721708330153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neamah HH, Sebert Kuhlmann AK, Tabak RG. Effectiveness of program modification strategies of the Diabetes Prevention Program: a systematic review. Diabetes Educ 2016;42(2):153–165. 10.1177/0145721716630386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barrera M Jr, Castro FG, Steiker LK. A critical analysis of approaches to the development of preventive interventions for subcultural groups. Am J Community Psychol 2011;48(3−4):439–454. 10.1007/s10464-010-9422-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Economos CD, Hyatt RR, Goldberg JP, et al. A community intervention reduces BMI z-score in children: Shape Up Somerville first year results. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15(5):1325–1336. 10.1038/oby.2007.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Economos CD, Tovar A. Promoting health at the community level: thinking globally, acting locally. Child Obes 2012;8(1):19–22. 10.1089/chi.2011.0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Estabrooks PA, Glasgow RE. Translating effective clinic-based physical activity interventions into practice. Am J Prev Med 2006;31 (suppl 4):S45–S56. 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jagosh J, Macaulay AC, Pluye P, et al. Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: implications of a realist review for health research and practice. Milbank Q. 2012;90(2):311–346. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barrera M Jr, Berkel C, Castro FG. Directions for the advancement of culturally adapted preventive interventions: local adaptations, engagement, and sustainability. Prev Sci 2017;18(6):640–648. 10.1007/s11121-016-0705-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brandt HM, Young VM, Campbell DA, Choi SK, Seel JS, Friedman DB. Federally qualified health centers’ capacity and readiness for research collaborations: implications for clinical-academic-community partnerships. Clin Transl Sci 2015;8(4):391–393. 10.1111/cts.12272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harden SM, Johnson SB, Almeida FA, Estabrooks PA. Improving physical activity program adoption using integrated research-practice partnerships: an effectiveness-implementation trial. Transl Behav Med 2017;7 (1):28–38. 10.1007/s13142-015-0380-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pieh-Holder KL, Callahan C, Young P. Qualitative needs assessment: healthcare experiences of underserved populations in Montgomery County, Virginia, USA. Rural Remote Health. 2012;12:1816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kessler R, Glasgow RE. A proposal to speed translation of healthcare research into practice: dramatic change is needed. Am J Prev Med 2011;40(6):637–644. 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.