Abstract

Background & Aims

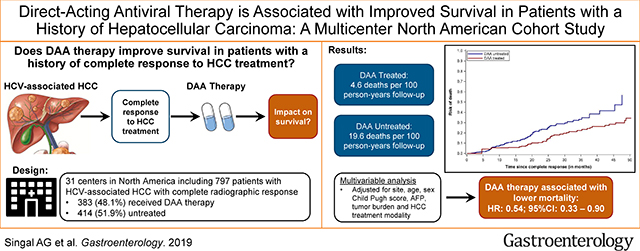

There is controversy over benefits of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection for patients with a history of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). We performed a multi-center cohort study to compare overall survival between patients with HCV infection treated with DAAs vs patients who did not receive DAA treatment for their HCV infection after complete response to prior HCC therapy.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients with HCV-related HCC who achieved a complete response to resection, local ablation, trans-arterial chemo- or radioembolization, or radiation therapy, from January 2013 through December 2017 at 31 healthcare systems throughout the United States and Canada. We used Cox proportional hazards regression to determine the association between receipt of DAA therapy, modeled as a time-varying covariate, and all-cause mortality, accounting for informative censoring and confounding using inverse probability weighting.

Results

Of 797 patients with HCV-related HCC, 383 patients (48.1%) received DAA therapy and 414 patients (51.9%) did not receive treatment for their HCV infection after complete response to prior HCC therapy. Among DAA-treated patients, 43 deaths occurred during 941 person-years of follow up, compared with 103 deaths during 526.6 person-years of follow up among patients who did not receive DAA therapy (crude rate ratio, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.16–0.33). In inverse probability-weighted analyses, DAA therapy was associated with a significant reduction in risk of death (hazard ratio [HR], 0.54; 95% CI, 0.33–0.90). This association differed by sustained virologic response (SVR) to DAA therapy; risk of death was reduced in patients with SVR to DAA therapy (HR, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.18–0.47) but not in patients without an SVR (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.55–2.33).

Conclusions

In an analysis of nearly 800 patients with complete response to HCC treatment, DAA therapy was associated with a significant reduction in risk of death.

Keywords: liver cancer, HCC, hepatitis C, survival

LAY SUMMARY

Treatment of hepatitis C virus with direct-acting antiviral agents in patients who have been successfully treated for liver cancer increases overall survival.

Graphical Abstract

BACKGROUND

Hepatocellular carcinoma is the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide and a leading cause of death in patients with compensated cirrhosis.(1) Given the majority of HCC cases occur in the setting of chronic liver disease, prognosis depends on both tumor burden and the degree of liver dysfunction. Most patients with HCC are diagnosed at late stages, with limited treatment options and a median survival of approximately one year.(2) Those diagnosed with HCC at an early stage are eligible for curative treatments, resulting in 5-year survival approaching 70%; however, outside of liver transplantation, these therapies are limited by a high risk of recurrence and a continued risk of hepatic decompensation.(3–6)

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection remains the most common cause of HCC in North America and Europe.(6) Several studies have reported a benefit of direct acting antiviral (DAA) therapy in reducing incident HCC and mortality among HCV-infected individuals(7–9), but the impact of these therapies on prognosis in patients who have had a complete response to HCC treatment is less clear. Interferon (IFN)-based therapy was associated with reduced risk of recurrence and mortality in patients with a history of HCC; however, there is uncertainty whether this was mediated by a direct IFN-mediated effect that would not translate to DAA-based therapy.(10) In fact, some early observational studies suggested a higher than expected risk of HCC recurrence after DAA therapy.(11) Subsequent studies have produced conflicting data, with most reporting no significant difference in recurrence between DAA-treated and untreated patients, including our multi-center North American study, in which we found no significant difference in overall recurrence, early recurrence, or recurrence aggressiveness.(9,12–16)

To date, most studies have focused on the association between DAA therapy and HCC recurrence, with fewer examining the association between DAA therapy and overall survival in patients with a history of HCC. Notably, data from ITA.LI.CA group demonstrated that hepatic decompensation may more strongly influence mortality in HCV-infected patients with a history of complete response to prior HCC therapy than HCC recurrence.(17) Therefore, DAA therapy may improve overall survival in patients with a history of HCC, independent of recurrence risk. The aim of this multi-center study was to compare overall survival between DAA-treated and untreated patients in a large cohort of North American patients with complete response to prior HCC-directed therapy.

METHODS

Study population

As previously described,(15) we conducted a multi-center retrospective cohort study of adult patients with HCV-related HCC who achieved HCC complete response between January 2013 and December 2017. In brief, patients were identified from 31 health systems throughout the United States and Canada. HCC diagnosis was based on characteristic radiologic appearance or histology per AASLD criteria.(18) Patients were required to have liver-localized tumor burden at presentation, and those with extrahepatic disease were excluded. We included patients who achieved complete HCC response by surgical resection, local ablative therapies, transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) or bland embolization, transarterial radioembolization (TARE) or stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT). Complete response to HCC treatment was defined by mRECIST criteria, i.e. disappearance of arterial enhancement from all HCC lesions on contrast-enhanced cross-sectional imaging. Patients with complete response after liver transplantation or systemic therapy were excluded.

We excluded patients who received IFN-based therapy or initiated DAA therapy prior to HCC complete response. We also excluded patients with unknown HCC response, e.g. lack of contrast-enhanced imaging after HCC treatment, and patients who died within 30 days of complete response. The study was approved by Institutional review boards at each study site.

Covariates

Demographic and clinical characteristics

We used a standardized data collection form to collect patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics from electronic medical records at time of HCC diagnosis, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, presence of hepatitis B (HBV) and HIV co-infection, platelet count, AST, ALT, HCV viral load, HCV genotype, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, and alpha fetoprotein (AFP). Degree of liver dysfunction was assessed by Child Pugh and MELD scores. Tumor burden, as determined by radiologists’ interpretation of imaging at each site, was categorized as very early stage (single tumor < 2 cm), early stage (single tumor < 5 cm or 2–3 tumors with each < 3 cm in maximum diameter), or intermediate stage (beyond early stage but without extra-hepatic spread). We also collected the type of treatment leading to complete response (surgical resection, ablation, TACE, other).

DAA treatment

We considered DAA treatment to be time-varying, allowing patients to switch between unexposed and exposed status. Specifically, we assigned follow-up time for patients before DAA initiation as unexposed time and time after DAA initiation as exposed time. Patients who initiated DAA therapy after liver transplantation only contributed unexposed time. For DAA-treated patients, we extracted information on treatment regimen, time from HCC complete response to DAA initiation, and outcome (i.e., sustained virological response [SVR]).

Statistical analyses

Primary analysis

We used Chi-square and Student’s t tests to characterize the study population by DAA treatment (DAA-treated vs. untreated). Because we allowed treatment to be time-varying, for this purpose, we defined DAA-treated patients as patients who initiated DAA at any time during follow-up, regardless of SVR.

For both DAA-treated and untreated patients, we defined the index date as the date of complete response to HCC treatment. We followed each patient from complete response to date of death, liver transplantation, or last clinic visit. We classified causes of death into four mutually exclusive categories: liver-related (e.g. acute on chronic liver failure, hepatorenal syndrome, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis); HCC-related (e.g. recurrent advanced stage HCC); non-liver/non-HCC related; and unknown (e.g. died elsewhere). The primary outcome was death from all causes, and we estimated the rate of all-cause mortality as the number of deaths divided by person-years of follow-up. We also calculated the crude mortality rate ratio as the ratio between the mortality rate among DAA-treated patients and that among untreated patients.

We then used a Cox proportional hazards regression model with inverse probability (IP) weights to examine overall survival between DAA-treated and untreated patients. Using this approach, each patient is weighted to create a pseudo-population in which: 1) DAA therapy is not associated with baseline covariates such that confounding is eliminated; and 2) censoring by liver transplantation is not associated with DAA therapy or covariates such that selection bias due to censoring is eliminated.(19,20) We used separate logistic regression models to estimate the probability of treatment (i.e., initiating DAA therapy) and for the probability of not being censored (i.e., not receiving liver transplant), including the following covariates: age, sex, Child Pugh class, tumor burden, AFP level, treatment leading to complete response, and time since complete response (censoring weight only). The resulting IP weight is the product of an estimated time-fixed IP treatment weight and an estimated time-varying IP censoring weight.

Sensitivity analysis

To assess the robustness of DAA treatment as a time-varying exposure, we performed a sensitivity analysis using a 180-day landmark. In this restricted subgroup, patients who initiated DAA within 180 days of complete response were categorized as DAA-treated, and those who did not initiate before 180 days were categorized as untreated. Patients who died, had HCC recurrence, received liver transplantation, or had their last clinic visit before the landmark were excluded. These restrictions avoid immortal time bias by synchronizing the start of follow-up for treated and untreated patients.(21,22) Survival by treatment group was then compared using Cox proportional hazards models with IP weights.

Secondary analyses

We hypothesized the association between DAA treatment and all-cause mortality differed among patients who achieved and did not achieve SVR. Therefore, we compared overall survival of DAA-treated patients with and without SVR to untreated patients. We also conducted secondary analyses stratified by tumor burden (within vs. beyond Milan criteria), treatment leading to HCC complete response (resection vs. ablation vs. TACE/SBRT), and HCC recurrence.

All tests were two-sided and performed at the 5% significance level. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC USA).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

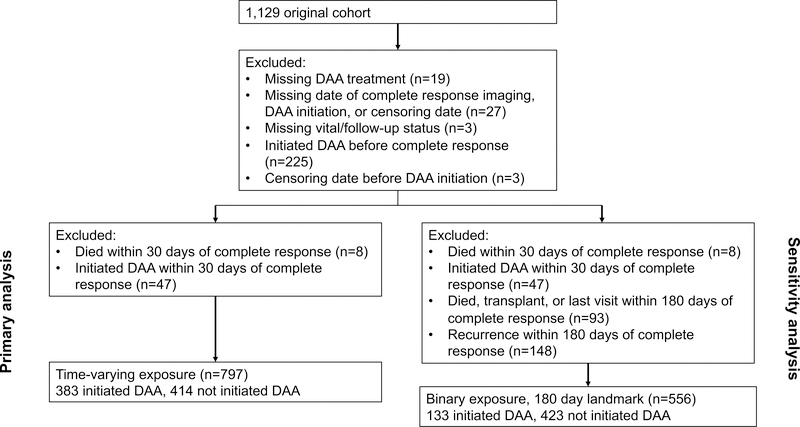

Selection of the study population is illustrated in Figure 1. Of 852 eligible HCV-infected HCC patients who achieved complete response to HCC-directed therapy between January 2013 and December 2017, we excluded 47 patients who initiated DAA therapy and 8 patients who died within 30 days of HCC complete response. There were 797 remaining patients included in the final analysis, of whom 383 initiated DAA therapy and 414 were untreated.

Figure 1.

Study cohort inclusion and exclusion diagram

Patient demographics are described in Table 1. Median age of patients was 61.5 years. Nearly three-fourths of patients were male and the cohort was racially diverse. At HCC diagnosis, nearly three-fourths of patients had a unifocal HCC and over 80% were within Milan Criteria. One-third of patients achieved HCC complete response from local ablation and 14% from surgical resection, while approximately half achieved complete response from locoregional therapies. A higher proportion of DAA-treated patients were older, non-Hispanic white, had compensated cirrhosis with less portal hypertension, achieved HCC complete response by resection than untreated patients; however, the two groups had similar tumor burden at diagnosis, including a similar proportion of patients presenting within Milan Criteria.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics, stratified by DAA treatment status

| Variable* | DAA-treated (n=383) | DAA-untreated (n=414) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at time of complete response (years) | 62.1 (58.6 – 66.1) | 61.2 (57.0 – 65.0) | 0.01 |

| Gender (% male) | 276 (72.1) | 320 (77.3) | 0.09 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.02 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 187 (48.8) | 159 (38.4) | |

| Hispanic White | 58 (15.1) | 66 (15.9) | |

| Black | 75 (19.6) | 92 (22.2) | |

| Other | 18 (4.7) | 22 (5.3) | |

| Missing | 45 (11.8) | 75 (18.1) | |

| Number of HCC nodules at diagnosis | 0.01 | ||

| One | 291 (77.2) | 270 (67.8) | |

| Two | 65 (17.2) | 88 (22.1) | |

| Three | 17 (4.5) | 25 (6.3) | |

| Four | 4 (1.1) | 15 (3.7) | |

| Maximum HCC diameter (cm) at diagnosis | 2.4 (1.7 – 3.3) | 2.6 (2.0 – 3.7) | 0.42 |

| HCC within Milan Criteria at diagnosis | 313 (82.6) | 332 (80.8) | 0.51 |

| AFP at time of HCC diagnosis (ng/mL) | 18.5 (7.3 – 67) | 18.3 (7.9 – 68) | 0.29 |

| Treatment leading to complete response | < 0.001 | ||

| Resection | 81 (21.2) | 33 (8.0) | |

| Local ablation | 138 (36.0) | 130 (31.4) | |

| TACE | 136 (35.5) | 222 (53.8) | |

| TARE/SBRT/other | 28 (7.3) | 28 (6.8) | |

| Number of HCC therapies required to achieve complete response | 0.13 | ||

| One | |||

| Two | 220 (60.8) | 205 (55.3) | |

| Three or more | 92 (25.4) | 95 (25.6) | |

| 50 (13.8) | 71 (19.1) | ||

| Child Pugh class at complete response | < 0.001 | ||

| Child Pugh A | 235 (61.4) | 199 (48.1) | |

| Child Pugh B | 127 (33.2) | 160 (38.7) | |

| Child Pugh C | 21 (5.5) | 55 (13.3) | |

| Presence of ascites | 98 (26.0) | 151 (37.8) | <0.001 |

| Presence of hepatic encephalopathy | 56 (14.9) | 89 (22.3) | 0.008 |

| Platelet count at complete response | 109 (75 – 158) | 87 (60 – 133) | < 0.001 |

| Bilirubin at complete response (mg/dL) | 1.0 (0.6 – 1.6) | 1.3 (0.7 – 2.1) | 0.18 |

| HCV genotype | < 0.001 | ||

| Genotype 1 | 293 (77.9) | 331 (69.6) | |

| Genotype 2 | 27 (7.2) | 17 (3.9) | |

| Genotype 3 | 43 (11.4) | 70 (14.9) | |

| Genotype 4 – 6 | 11 (2.9) | 17 (2.9) | |

| Viral co-infection | 0.38 | ||

| Hepatitis B | 8 (2.2) | 5 (1.3) | |

| HIV | 9 (2.5) | 6 (1.6) | |

| DAA regimen** | |||

| Sofosbuvir/ledipasvir | 237 (63.0) | ||

| Sofosbuvir | 56 (14.9) | ||

| Simeprevir/sofosbuvir | 32 (8.5) | N/A | |

| Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir | 18 (4.8) | ||

| Daclatasvir/sofosbuvir | 16 (4.3) | ||

| 7 (1.9) | |||

| Ombitasvir/partiprevir/ritonavir/dasabuvir | 3 (0.8) | ||

| Elbasavir/grazoprevir | 7 (1.9) | ||

| Other | |||

| DAA regimen duration | |||

| Less than 12 weeks | 15 (4.0) | ||

| 12 weeks | 197 (53.1) | N/A | |

| >12 weeks but < 24 weeks | 26 (7.0) | ||

| 24 weeks | 126 (34.0) | ||

| Greater than 24 weeks | 7 (1.9) | ||

| Time from HCC complete response to DAA | |||

| Less than 3 months | 76 (20.2) | ||

| >3 – 6 months | 81 (21.5) | N/A | |

| >6 – 12 months | 96 (25.5) | ||

| >12 – 24 months | 92 (24.4) | ||

| Greater than 24 months | 32 (8.5) | ||

Continuous data presented as median (IQR)

All DAA regimens are with or without ribavirin

AFP – alpha fetoprotein; DAA – direct acting antiviral; HCC – hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV – hepatitis C virus; SBRT – stereotactic body radiation therapy; TACE – transarterial chemoembolization; TARE – transarterial radioembolization

Median time from HCC diagnosis to HCC treatment was 2.7 (IQR 1.4 – 5.6) months, and median time from HCC treatment to complete response was 1.6 (IQR 1.1 – 3.2) months. Median time from HCC complete response to DAA initiation was 7.7 (IQR 3.6 – 14.1) months, with 20.2% treated within 3 months, 21.5% between 3–6 months, 25.5% between 6–12 months, and 32.9% more than 12 months after HCC complete response. SVR was documented in 79.4% of DAA-treated patients, while 11.5% had treatment-failure and 9.1% did not have documented assessment of SVR.

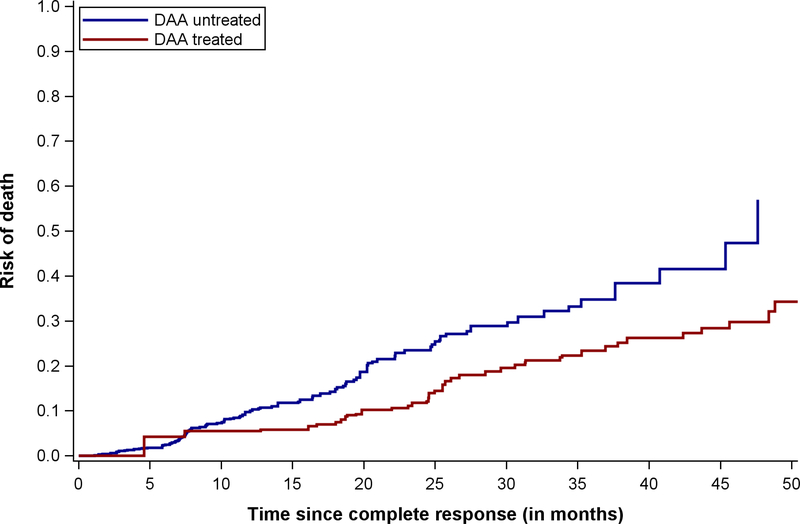

Association between DAA Therapy and Overall Survival

Among DAA-treated patients, 43 deaths occurred during 941.0 person-years of follow-up compared to 103 deaths during 526.6 person-years of follow-up among untreated patients, yielding a crude rate ratio of 0.23 (95%CI 0.16 – 0.33). The 1- and 2-year risk of mortality for DAA-treated patients was 5.5% and 11.8%, compared to 10.0% and 23.5% among untreated patients. The median time from HCC complete response to death among DAA-treated patients was 25.7 (IQR 19.4 – 33.9) months compared to 11.5 (IQR 7.1 – 20.2) months for untreated patients. The proportion of deaths that were liver-related was significantly lower in DAA-treated than untreated patients (16.3% vs. 34.0%, p=0.03), whereas the proportion of HCC-related deaths was similar between the two groups (30.2% vs. 29.1%, p=0.89).

In the primary analysis, DAA therapy was associated with reduced mortality in crude (HR 0.37, 95%CI 0.26 – 0.54) and weighted (HR 0.54, 95%CI 0.33 – 0.90) models (Table 2). In the sensitivity analysis using a 180-day landmark, DAA therapy was associated with reduced mortality (weighted HR 0.57, 95%CI 0.30 – 1.09); however, few patients were classified as DAA-treated (n=133), and the effect estimate did not reach statistical significance.

Table 2.

Associations between DAA treatment and mortality in HCV-infected patients with HCC

| Patients | Deaths | Person-years | Mortality rate (per 100 person years) | Crude rate ratio | Adjusted HR* | Sample size in adjusted HR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAA treatment as time-varying exposure† | |||||||

| Overall | |||||||

| Untreated | 414 | 103 | 526.63 | 19.56 (16.05, 23.62) | 401 | ||

| DAA-treated | 383 | 43 | 941.01 | 4.57 (3.35, 6.09) | 0.23 (0.16, 0.33) | 0.54 (0.33, 0.90) | 339 |

| Within Milan | |||||||

| Untreated | 332 | 83 | 427.95 | 19.35 (15.55, 23.91) | 323 | ||

| DAA-treated | 313 | 38 | 777.54 | 4.89 (3.51, 6.63) | 0.25 (0.17, 0.37) | 0.56 (0.32, 0.98) | 280 |

| Beyond Milan | |||||||

| Untreated | 79 | 18 | 96.22 | 18.71 (11.48, 28.93) | 78 | ||

| DAA-treated | 66 | 5 | 155.00 | 3.23 (1.22, 7.07) | 0.17 (0.06, 0.46) | 0.53 (0.21, 1.39) | 59 |

| Surgical resection | |||||||

| Untreated | 33 | 9 | 58.91 | 15.28 (7.55, 27.89) | 30 | ||

| DAA-treated | 81 | 5 | 235.89 | 2.12 (0.80, 4.65) | 0.14 (0.05, 0.41) | 0.21 (0.06, 0.76) | 73 |

| Local ablation | |||||||

| Untreated | 130 | 42 | 174.59 | 24.06 (17.58, 32.19) | 123 | ||

| DAA-treated | 138 | 13 | 326.02 | 3.99 (2.23, 6.63) | 0.17 (0.09, 0.31) | 0.26 (0.13, 0.51) | 116 |

| TACE | |||||||

| Untreated | 222 | 43 | 264.59 | 16.25 (11.92, 21.67) | 220 | ||

| DAA-treated | 136 | 23 | 312.42 | 7.36 (4.79, 10.86) | 0.45 (0.27, 0.75) | 0.99 (0.47, 2.08) | 129 |

| Child Pugh A | |||||||

| Untreated | 199 | 45 | 301.80 | 14.91 (11.02, 19.76) | 191 | ||

| DAA-treated | 235 | 17 | 600.47 | 2.83 (1.71, 4.43) | 0.19 (0.11, 0.33) | 0.25 (0.14, 0.48) | 206 |

| Child Pugh B | |||||||

| Untreated | 160 | 44 | 182.43 | 24.12 (17.76, 32.07) | 155 | ||

| DAA-treated | 127 | 18 | 303.71 | 5.93 (3.64, 9.17) | 0.25 (0.14, 0.43) | 0.43 (0.24, 0.79) | 116 |

| Child Pugh C | |||||||

| Untreated | 55 | 14 | 42.40 | 33.02 (18.91, 53.92) | 55 | ||

| DAA-treated | 44 | 11 | 36.83 | 3.62 (1.92, 6.27) | 0.90 (0.41, 1.99) | 1.92 (0.56, 6.51) | 17 |

| Recurrence | |||||||

| Untreated | 205 | 62 | 326.40 | 19.00 (14.70, 24.18) | 196 | ||

| DAA-treated | 209 | 39 | 535.88 | 7.28 (5.25, 9.84) | 0.38 (0.26, 0.57) | 0.86 (0.49, 1.52) | 184 |

| No recurrence | |||||||

| Untreated | 199 | 40 | 197.62 | 20.24 (14.67, 27.27) | 195 | ||

| DAA-treated | 174 | 4 | 405.13 | 0.99 (0.33, 2.35) | 0.05 (0.02, 0.14) | 0.09 (0.02, 0.29) | 155 |

| No prior recurrence | |||||||

| Untreated | 400 | 95 | 508.91 | 18.67 (15.19, 22.71) | 387 | ||

| DAA-treated | 372 | 43 | 917.13 | 4.69 (3.44, 6.25) | 0.25 (0.18, 0.36) | 0.57 (0.34, 0.94) | 329 |

| Using 180-day landmark‡ | |||||||

| Overall | |||||||

| Untreated | 423 | 73 | 714.16 | 10.22 (8.07, 12.78) | 394 | ||

| DAA-treated | 133 | 11 | 204.14 | 5.39 (2.86, 9.33) | 0.53 (0.28, 0.99) | 0.57 (0.30, 1.09) | 115 |

Adjusted for age, sex, Child Pugh class, HCC tumor stage, AFP level, and type of HCC treatment

Exposure to DAAs modeled as a time-dependent covariate

DAA group includes patients who initiated DAA therapy within 180 days from HCC complete response. Patients who died, developed recurrence, received liver transplantation, or had their last clinic visit within 180 days were excluded.

DAA – direct acting antiviral; HCC – hepatocellular carcinoma; SVR – sustained virological response; TACE – transarterial chemoembolization

Subgroup analyses are detailed in Table 2. DAA therapy was associated with improved survival among patients with Child Pugh A or B cirrhosis; assessing mortality benefit in those with Child C cirrhosis was limited by small sample size. We also observed a consistent benefit of DAA therapy among patients who initially had tumor burden within and beyond Milan Criteria. The reduction in mortality with DAA therapy was greater in patients who received resection or ablation than in those who received TACE, (interaction p-value=0.03). Results were consistent in the subgroup of patients without prior history of HCC recurrence. However as expected, there was a significantly greater benefit of DAA therapy in patients who remained recurrence-free during the study period (HR 0.09, 95%CI 0.02 – 0.29) compared to those who experienced HCC recurrence (HR 0.86, 95%CI 0.49 – 1.52) (interaction p-value<0.001).

Association between DAA Therapy and Overall Survival, Stratified by SVR Status

We expected the association between DAA therapy and mortality to differ by SVR and examined DAA-treated patients with and without SVR in greater detail. Characteristics of DAA-treated patients, stratified by SVR status, are detailed in Supplemental Table 1. Patients with SVR were more likely to be female and non-Hispanic white, but they had a similar number of HCC nodules, maximum tumor diameter, proportion within Milan Criteria at diagnosis, as well as type and number of treatments leading to HCC complete response. We also found no significant difference in the degree of liver dysfunction at complete response, HCV genotype, type and duration of DAA regimen, and timing of treatment from HCC complete response. Although a higher proportion of patients with SVR subsequently underwent liver transplantation, this difference did not reach statistical significance (22.7% vs. 13.6%, p=0.17).

Among DAA-treated patients, patients with SVR had significantly reduced mortality from time of DAA initiation compared to non-SVR patients (HR 0.27, 95%CI 0.13 – 0.57). In a sensitivity analysis in which patients with missing SVR status were assumed to be non-SVR, SVR continued to be associated with reduced mortality (HR 0.47, 95%CI 0.35 – 0.64). We next compared both groups of DAA-treated patients (with and without SVR) to untreated patients. DAA-treated patients who achieved SVR had significantly reduced mortality compared to untreated patients (HR 0.29, 95%CI 0.18 – 0.47); however, a mortality benefit was not observed among DAA-treated patients who did not achieve SVR compared to untreated patients (HR 1.13, 95%CI 0.55–2.33).

DISCUSSION

There has been extensive debate about the potential benefit of DAA therapy in patients with a history of HCC, primarily related to concerns about the risk of HCC recurrence. While recent data have suggested that DAA therapy after complete HCC response does not appear to increase recurrence, to the best of our knowledge our study represents the first to demonstrate a survival benefit of DAA therapy in this patient population.

Although HCC treatments such as surgical resection and local ablative therapies are potentially curative, they are limited by high risk of recurrence and 5-year mortality approaches 50%. Prior attempts to identify adjuvant therapies to reduce HCC recurrence, such as the STORM Trial evaluating sorafenib after resection or ablation, largely failed.(23) Cabbibo and colleagues recently demonstrated that hepatic decompensation was a stronger driver of mortality than HCC recurrence in patients with complete response to HCC therapy, suggesting interventions that reduce portal hypertension and other manifestations of advanced liver disease could improve survival.(17) Albeit of limited sample size, results from the ANRS CirVir prospective cohort study suggested a potential benefit of DAA-associated SVR to reduce hepatic decompensation in patients with HCC.(24) Hepatic decompensation was one of the most common causes of death in patients without SVR but was not observed in any of the four patients with SVR. Similarly, Bruno and colleagues found that over one-third of HCC patients with untreated HCV infection died of hepatic decompensation compared to 0 of 19 patients who had achieved SVR prior to HCC diagnosis.(25) However, these studies both evaluated the benefit of SVR prior to HCC diagnosis, where there may be a longer time frame to experience fibrosis regression and improvement in portal hypertension.(26,27) Our study adds to this literature and reinforces that DAA therapy may also reduce mortality in patients with a history of HCC.

Although DAA therapy was associated with a consistent survival benefit across most patient subgroups, this association was mitigated in those who were treated with TACE as well as those with HCC recurrence, likely due to a higher risk of HCC mortality. Although DAA therapy can help improve or stabilize liver function in these patients, the high risk of recurrence and persistent HCC-related mortality highlights a continued need for adjuvant therapy after HCC complete response. In the absence of proven adjuvant agents, close surveillance after complete response may increase early tumor detection and minimize HCC-related mortality.(28,29) As previously reported, over two-thirds of patients with recurrence in our study were detected at an early stage (BCLC stage 0/A), and over 50% of those with known treatment response had an objective response.(15) It is important to note that although the association between DAA therapy and survival was not statistically significant in these subgroups, the samples sizes were too small to make definitive conclusions, and the point estimates still suggested a potential benefit. Further studies are needed in these patients to determine if DAA therapy may be of potential benefit.

Although we observed a benefit of DAA therapy in patients with a history of HCC, the optimal timing of DAA therapy in relation to HCC treatment remains unclear. Should patients initiate DAA therapy concurrent with HCC treatment, immediately thereafter, or is it best to wait for documented complete response? Although some studies suggest a lower proportion of patients with active HCC achieve SVR, it is unclear if this concern should drive decisions of timing.(9,30–32) If the potential benefit of DAA therapy is truly related to preventing liver dysfunction, earlier treatment may be better. Extending this further is the question if DAA therapy would have similar benefits among patients with active intermediate-stage or even advanced stage HCC.(33) Further studies in these patient populations to address these important clinical dilemmas are clearly needed.

It is possible that the association between DAA therapy and reduced mortality may be driven by confounding, with DAA therapy being selectively used in patients with better prognosis. We attempted to adjust for measured confounders and selection bias with IP-weighting, and we mitigated the effect of immortal time bias by using time-varying and landmark analyses. Further, we observed no association between DAA therapy and survival among those who were treated but did not achieve SVR. We acknowledge still the potential for residual confounding. For example, DAA-treated patients had less portal hypertension than untreated patients, which could partly explain results.

Results from our study must be interpreted in light of other potential limitations. First, we used imaging interpretation through routine clinical care instead of centralized imaging review, which could have affected classification of HCC complete response.(34) However, all included health systems were academic centers with GI-trained radiologists, and most centers use multidisciplinary tumor boards.(35,36) Importantly, reduction in mortality were most evidence in patients undergoing surgical resection or ablation which would be less prone to misclassification of complete response. The weaker association between DAA therapy and reduced mortality in patients undergoing TACE may have been partly related to unrecognized microscopic residual disease. Second, approximately 9% of patients were lost to follow-up, with a higher proportion in the DAA-untreated group. Finally, we did not have data on incident development of hepatic decompensation during study follow-up and were unable to demonstrate whether the survival benefit we observed was definitively related to preservation of liver function. Ongoing multi-center prospective cohort studies with longer follow-up will hopefully address some of these limitations; however these are years away from reporting. These limitations were felt to be outweighed by the study’s notable strengths, including its multi-center design, large cohort of patients, rigorous statistical analysis plan, and inclusion of a contemporary untreated comparison group.

In summary, DAA therapy was associated with a significant reduction in mortality among HCV-infected patients with documented complete response to HCC therapy. Overall, our results suggest use of DAA therapies is likely beneficial in HCV-infected patients with a history of HCC.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Overall survival, stratified by receipt of direct acting antiviral hepatitis C therapy

What you need to know.

Background & Context

Direct acting antiviral (DAA) treatment is associated with increased survival in patients with cirrhosis, but little is known about its effect in patients with a history of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

New Findings

DAA therapy for patients who had a complete response to HCC therapy is associated with increased overall survival, as long as the patients had a sustained virologic response to DAA treatment, which reduces liver-related mortality.

Limitations

This was a retrospective cohort study with possible selection bias and residual confounding.

Impact

Patients with HCV-related HCC who have a confirmed complete response should be considered for DAA treatment, which can increase survival.

Acknowledgments

Financial Source: This study was conducted with support National Cancer Institute (NCI) R01 CA222900 and grant support from Abbvie. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or Abbvie. The funding agencies had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

Amit Singal was on speakers bureau for Gilead, Bayer, and Bristol Meyers Squibb. He has served on advisory boards for Gilead, Abbvie, Bayer, Eisai, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Wako Diagnostics, and Exact Sciences. He serves as a consultant to Bayer, Eisai, Exelixis, Roche, Exact Sciences, and Glycotest. He has received research funding from Gilead and Abbvie.

Neil Mehta has received research funding from Wako Diagnostics.

Anjana Pillai serves as a consultant and is on speakers bureau for Eisai and BTG.

Jordan Feld has received research support from Gilead, Abbvie, Merck, and Janssen.

Binu John has served on advisory boards for Eisai.

Catherine Frenette is on speakers bureaus for Bayer, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, Abbvie, and Eisai. She served on advisory boards for Gilead, Eisai, and Wako. She served as a consultant for Bayer and Gilead. She received research funding from Bayer.

Parvez Mantry is on speakers bureaus and served on advisory boards for Gilead, Abbvie, Bayer, BMS, Eisai, Merck, and BTG. He has received research funding from Gilead and Sirtex.

Michael Leise has received research funding from Abbvie.

Kalyan Ram Bhamidimarri serves as scientific advisory board member for Gilead, Merck, and Abbvie. He has received research funding from Gilead.

Laura Kulik is on speakers bureau for Eisai, Gilead, and Dova. She serves as an advisory board member for BMS, Eisai, Bayer, Exelixis

Reena Salgia is on speakers bureau for Bayer. She has served on advisory boards for Bayer, Eisai, and Exelixis.

Sanjaya Satapathy has received Grant/research support from Biotest, Conatus, Genfit, Gilead Sciences, Intercept, Dova, Bayer, Exact Sciences, and Shire; served on the Advisory board or as consultant for Abbvie, Gilead Sciences, and Intercept; and on the speakers bureau for Intercept, Dova, and Alexion.

Robert Wong is on the speakers bureau, served as consultant and on advisory boards, and has received research funding from Gilead. He has also received research funding from Abbvie. He was on the speakers bureau for Bayer.

Neehar Parikh serves as a consultant to Exelexis and Bristol-Myers Squibb. He has served on advisory boards for Eisai and Bayer.

Andrea Branch served as a consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim and has received research support from Gilead.

None of the other authors have any relevant conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

- AASLD

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

- AFP

alpha fetoprotein

- BCLC

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

- DAA

direct acting antiviral

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- IFN

interferon

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- SBRT

stereotactic body radiation therapy

- SVR

sustained virological response

- TACE

transarterial chemoembolization

- TARE

transarterial radioembolization

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Amit G. Singal, Division of Digestive and Liver Disease, UT Southwestern Medical Center

Nicole E. Rich, Division of Digestive and Liver Disease, UT Southwestern Medical Center

Neil Mehta, Division of Gastroenterology, University of California San Francisco.

Andrea D. Branch, Department of Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Anjana Pillai, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, University of Chicago.

Maarouf Hoteit, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Pennsylvania.

Michael Volk, Transplantation Institute and Division of Gastroenterology, Loma Linda University Health.

Mobolaji Odewole, Division of Digestive and Liver Disease, UT Southwestern Medical Center.

Steven Scaglione, Division of Hepatology, Loyola University Medical Center and Edward Hines Veterans Affairs.

Jennifer Guy, Department of Transplantation, California Pacific Medical Center.

Adnan Said, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine.

Jordan J. Feld, Toronto Center for Liver Disease, Toronto General Hospital

Binu V. John, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, McGuire VA Medical Center

Catherine Frenette, Division of Organ Transplantation, Scripps Green Hospital.

Parvez Mantry, Liver Institute at Methodist Dallas.

Amol S. Rangnekar, Division of Gastroenterology, Georgetown University Hospital

Omobonike Oloruntoba, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Duke University Health Center.

Michael Leise, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic.

Janice H. Jou, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Oregon Health and Science University

Kalyan Ram Bhamidimarri, Division of Hepatology, University of Miami Miller School or Medicine.

Laura Kulik, Division of Hepatology, Northwestern University.

George N. Ioannou, Division of Gastroenterology and Research and Development, Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Healthcare System and University of Washington

Annsa Huang, Division of Gastroenterology, University of California San Francisco.

Tram Tran, Liver Disease and Transplant Center, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

Hrishikesh Samant, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center.

Renumathy Dhanasekaran, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Stanford University.

Andres Duarte-Rojo, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

Reena Salgia, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Henry Ford Hospital.

Sheila Eswaran, Division of Gastroenterology, Rush Medical College.

Prasun Jalal, Division of Abdominal Transplantation, Baylor College of Medicine.

Avegail Flores, Division of Gastroenterology, Washington University School of Medicine.

Sanjaya K. Satapathy, Division of Hepatology, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine, Northshore University Hospital, Northwell Health, Manhasset, New York

Sofia Kagan, Division of Digestive and Liver Disease, UT Southwestern Medical Center.

Purva Gopal, Department of Pathology, UT Southwestern Medical Center.

Robert Wong, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Alameda Health System.

Neehar D. Parikh, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Michigan.

Caitlin C. Murphy, Division of Digestive and Liver Disease, UT Southwestern Medical Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cronin KA, Lake AJ, Scott S, Sherman RL, Noone AM, Howlander N, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, part I: National cancer statistics. Cancer. 2018; doi: 10.1002/cncr.31551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altekruse SF, McGlynn KA, Dickie LA, Kleiner DE. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Confirmation, Treatment, and Survival in Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Registries, 1992 – 2008. Hepatology 2012; 55(2): 476–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shiina S, Tateishi R, Arano T, Uchino K, Enooku K, Nakagawa H, et al. Radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: 10-year outcome and prognostic factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(4):569–77; quiz 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabrizian P, Jibara G, Shrager B, Schwartz M, Roayaie S. Recurrence of hepatocellular cancer after resection: patterns, treatments, and prognosis. Ann Surg. 2015;261(5):947–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Golfieri R, Renzulli M, Mosconi C, Forlani L, Giampalma E, Piscaglia F, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma responding to superselective transarterial chemoembolization: an issue of nodule dimension? J Vasc Interv Radiol 2013; 24(4): 509–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kulik L and El-Serag HB. Epidemiology and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2019; 156(2): 477–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ioannou GN, Green PK, Berry K. HCV eradication induced by direct-acting antiviral agents reduces the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2019. (in press, doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.08.030) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calvaruso V, Cabibbo G, Cacciola I, Petta S, Madonia S, Bellia A, et al. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with HCV-associated cirrhosis with direct-acting antiviral agents. Gastroenterology 2018; 155:411–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singal AG, Lim JK, Kanwal F. AGA Clinical Practice Update: Interaction between Oral Direct-Acting Antivirals (DAAs) for Chronic Hepatitis C Infection and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2019; 156(8): 2149–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breitenstein S, Dimitroulis D, Petrowsky H, Puhan MA, Mullhaupt B, Clavien PA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of interferon after curative treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with viral hepatitis. Br J Surg 2009; 96(9): 975–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reig M, Boix L, Marino Z, Torres F, Forns X, Bruix J. Liver cancer emergence associated with antiviral treatment: an immune surveillance failure? Semin Liver Dis 2017;37:109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ANRS Collaborative Study Group. Lack of evidence of an effect of direct-acting antivirals on the recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma: Data from three ANRS cohorts. J Hepatol 2016;65:734–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cabibbo G, Petta S, Calvaruso V, Cacciola I, Cannavo MR, Madonia S, et al. In early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV cirrhotic patients affected by treatment with direct-acting antivirals? A prospective multi-center study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017; 46(7):688–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saraiya N, Yopp AC, Rich NE, Odewole M, Parikh ND, Singal AG. Systematic review with meta-analysis: recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma following direct-acting antiviral therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018; 58;127–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singal AG, Rich NE, Mehta N, Branch A, Pillai A, Hoteit MA, et al. Direct acting antiviral therapy is not associated with recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma: A multi-center North American Cohort Study. Gastroenterology 2019; 156(6): 1683–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waziry R, Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, Amin J, Law M, Danta M, George J, Dore GJ. Hepatocellular carcinoma risk following direct-acting antiviral HCV therapy: A systematic review,meta-analyses, and meta-regression. J Hepatol 2017;67:1204–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cabibbo G, Petta S, Barbara M, Attardo S, Bucci L, Farinati F, et al. Hepatic decompensation is the major driver of death in HCV-infected cirrhotic patients with successfully treated early hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2017; 67(1): 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, Zhu AX, Finn RS, Abecassis M, et al. Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2018; 68(2): 723–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buchanan AL, Hudgens MG, Cole SR, Lau B, Adimora AA, Women’s Interagency HIV Study. Worth the weight: using inverse probability weighted Cox models in AIDS research. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2014; 30(12): 1170–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cole SR and Hernan MA. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. Am J Epidemiol 2008; 168(6): 656–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho IS, Chae YR, Kim JH, Yoo HR, Jang SY, Kim GR, et al. Statistical methods for elimination of guarantee-time bias in cohort studies: a simulation study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1):126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gleiss A, Oberbauer R, Heinze G. An unjustified benefit: immortal time bias in the analysis of time-dependent events. Transpl Int. 2018;31(2):125–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruix J, Takayama T, Mazzaferro V, Chau GY, Yang J, Kudo M, et al. Adjuvant sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma after resection or ablation (STORM): a phase 3 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16(13): 1344–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nahon P, Bourcier V, Layese R, Audureau E, Cagnot C, Marcellin P, et al. Eradication of Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Patients with Cirrhosis Reduces Risk of Liver and Non-liver Complications. Gastroenterology 2017; 152(1): 142–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bruno S, Di Marco V, Iavarone M, Roffi L, Boccaccio V, Crosignani A, et al. Improved survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and compensated hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis who attained sustained virological response. Liver Int 2017; 37(10): 1526–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mandorfer M, Kozbial K, Schwabl P, Freissmuth C, Schwarzer R, Stern R, et al. Sustained virologic response to interferon-free therapies ameliorates HCV-induced portal hypertension. J Hepatol 2016; 65(4): 692–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lens S, Alvarado-Tapias E, Marino Z, Londono MC, Llop E, Martinez J, et al. Effects of All-Oral Anti-Viral Therapy on HVPG and Systemic Hemodynamics in Patients with Hepatitis C Virus-Associated Cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2017; 153(5): 12731283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singal AG, Pillai A, Tiro J. Early detection, curative treatment, and survival rates for hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in patients with cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2014; 11(4): e1001624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi DT, Kum H, Park S, Ohsfeldt RL, Parikh ND, Singal AG. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Screening is Associated with Increased Survival of Patients with Cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 17(5): 976–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prenner SB, Van Wagner LB, Flamm SL, Salem R, Lewandowski RJ, Kulik L. Hepatocellular carcinoma decreases the chance of successful hepatitis C virus therapy with direct-acting antivirals. J Hepatol 2017; 66:1173–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beste LA, Green PK, Berry K, Kogut MJ, Allison SK, Ioannou GN. Effectiveness of hepatitis C antiviral treatment in a USA cohort of veteran patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2017; 67:32–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Radhakrishnan K, Di Bisceglie AM, Reddy KR, Lim JK, Levitsky J, Kuo A, et al. Impact of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and tumor treatment on sustained virologic response (SVR) rates with direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy for hepatitis C: HCV-TARGET results. Hepatology 2017; 66:755A. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cabibbo G, Celsa C, Camma C, Craxi A. Should we cure hepatitis C virus in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma while treating cancer? Liver Int 2018; 38(12): 2108–2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mariño Z, Darnell A, Lens S, Sapena V, Díaz A, Belmonte E, et al. Time association between hepatitis C therapy and hepatocellular carcinoma emergence in cirrhosis: relevance of non-characterized nodules. J Hepatol 2019; 70(5): 874–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Serper M, Taddei TH, Mehta R, D’Addeo K, Dai F, Aytaman A, et al. Association of Provider Specialty and Multidisciplinary Care With Hepatocellular Carcinoma Treatment and Mortality. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(8):1954–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yopp AC, Mansour JC, Beg MS, Arenas J, Trimmer C, Reddick M, et al. Establishment of a multidisciplinary hepatocellular carcinoma clinic is associated with improved clinical outcome. Annals of surgical oncology. 2014;21(4):1287–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.