Abstract

Portal hypertension (PHT) in advanced chronic liver disease (ACLD) results from increased intrahepatic resistance caused by pathologic changes of liver tissue composition (structural component) and intrahepatic vasoconstriction (functional component). PHT is an important driver of hepatic decompensation such as development of ascites or variceal bleeding. Dysbiosis and an impaired intestinal barrier in ACLD facilitate translocation of bacteria and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) that promote disease progression via immune system activation with subsequent induction of proinflammatory and profibrogenic pathways. Congestive portal venous blood flow represents a critical pathophysiological mechanism linking PHT to increased intestinal permeability: The intestinal barrier function is affected by impaired microcirculation, neoangiogenesis, and abnormal vascular and mucosal permeability. The close bidirectional relationship between the gut and the liver has been termed “gut-liver axis”. Treatment strategies targeting the gut-liver axis by modulation of microbiota composition and function, intestinal barrier integrity, as well as amelioration of liver fibrosis and PHT are supposed to exert beneficial effects. The activation of the farnesoid X receptor in the liver and the gut was associated with beneficial effects in animal experiments, however, further studies regarding efficacy and safety of pharmacological FXR modulation in patients with ACLD are needed. In this review, we summarize the clinical impact of PHT on the course of liver disease, discuss the underlying pathophysiological link of PHT to gut-liver axis signaling, and provide insight into molecular mechanisms that may represent novel therapeutic targets.

Keywords: Cirrhosis, Portal hypertension, Gut-liver axis, Bacterial translocation, Intestinal barrier, Farnesoid X receptor

Core tip: In advanced chronic liver disease, portal hypertension (PHT) results from increased intrahepatic resistance and leads to splanchnic vasodilation and patholocgical neoangiogenesis. Gut dysbiosis, increased intestinal permeability, translocation of bacteria and pathogen-associated molecular patterns promote liver disease progression via immune system activation and subsequent induction of a proinflammatory state. The close relationship between gut and liver and their bidirectional interaction has been termed gut-liver axis. This review describes the impact of PHT on the gut-liver axis by providing insight into pathophysiology and summarizing important clinical observations and potential therapeutic strategies.

INTRODUCTION

Advanced chronic liver disease (ACLD)/cirrhosis represents a significant health burden, accounting for considerable morbidity and mortality worldwide[1]. Cirrhosis was found responsible for about 1.0 million deaths in 2010[2] and for 1.2 million deaths in 2013[3], indicating an increasing trend over the years. Recent epidemiological data from Europe displays heterogeneity regarding prevalence, etiology, and mortality trends in different European countries and suggests that public health action and prudent treatment strategies might exert considerable public health benefits[4].

The clinical course of ACLD can be divided in a compensated and decompensated stage[5,6]. The compensated stage may last for several years[5], while the development of typical complications of cirrhosis, i.e., most commonly ascites but also variceal hemorrhage or hepatic encephalopathy (i.e., acute decompensation, AD) defines the progression to the decompensated stage. Furthermore, patients with ACLD are at risk for developing organ failures, i.e., acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF), a syndrome associated with a high risk of mortality[7-11].

The development of portal hypertension (PHT) holds a central role in the progression of liver disease, as it drives hepatic decompensation and other complications of cirrhosis[5,12]. Based on a body of evidence propagating an impact of gut microbiota, intestinal barrier integrity, and bacterial translocation (BT) on the course of liver disease, the term “gut-liver axis” has arisen over the last few years, subsuming the close relationship between the gut and the liver in different entities of ACLD[13-15]. BT (migration from intestinal bacteria and/or their products beyond the intestinal barrier) impacts on the course of disease in cirrhosis by promoting or precipitating AD, ACLF, and finally, mortality. Hence, the gut-liver axis has gained considerable scientific interest[5,16,17]. The aim of this review is to summarize current knowledge on pathophysiological links between gut-liver axis signaling and PHT, and to provide additional insights into the effects of established and investigational therapeutic approaches. The search strategy and selection criteria of this study are shown in Supplemental materials.

PORTAL HYPERTENSION AND IMMUNE SYSTEM ACTIVATION

Portal hypertension and bacterial translocation are linked to clinical events

Characteristic histological features of cirrhosis include diffuse nodular regeneration enclosed by fibrotic septa, leading to parenchymal loss-of-function and destruction of liver structure caused by necroinflammation and fibrogenesis due to ACLD[18-20]. These structural changes deteriorate the vascular (sinusoidal) architecture and promote intrahepatic vasoconstriction which leads to an increase in intrahepatic resistance[20-22]. Along with progressive increases of portal blood flow, the elevated intrahepatic resistance leads to the development of PHT[20,21]. The measurement of the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) is the gold standard for assessing sinusoidal PHT with an HVPG ≥ 10 mmHg defining clinically significant PHT (CSPH)[20,23]. The formation of portosystemic collaterals such as varices as well as clinical events that define hepatic decompensation and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) development are strongly associated with CSPH[20,23,24].

Importantly, the portal vein is anatomically linked to the venous blood flow drained from splanchnic organs and the intestines. While subclinical PHT is primarily due to increased intrahepatic resistance, the development of hyperdynamic circulation in patients with CSPH[25,26] further deteriorates PHT. Hyperdynamic circulation emerges from splanchnic vasodilation caused by an increased release of vasodilating molecules and a decreased responsiveness to vasoconstrictors. However, it still remains unclear at which stage the mucosal barrier is affected by PHT. Resulting BT is believed to promote liver disease progression and aggravate splanchnic vasodilation[12].

The reduction of effectively circulating blood volume resulting from splanchnic pooling induces a vicious circle via activation of compensatory measures, such as the sympathetic nervous and renin-angiotensin-aldosteron systems. These mechanisms aim to increase circulating blood volume to ensure adequate organ perfusion[12,27,28]. This state is characterized by an increment of heart rate and cardiac output as well as decreased systemic vascular resistance[21,29]. In turn, portal venous inflow increases and further exacerbates PHT[25].

Pathophysiological background on inflammation and bacterial translocation

The identification of Toll-like receptor (TLR) involvement in gut-liver-signaling has provided important evidence for the link between inflammation and innate immunity in ACLD. TLRs are mammalian analogues of pattern-recognition receptors and capable of recognizing pathogens or pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs)[30]. PAMPs are products of microbial metabolism that are specifically produced by pathogens and not by the host[31]. The term comprises different molecule types, such as lipids and nucleic acids[32]. Some TLRs recognize a diverse structural spectrum of ligands. For example, TLR4 recognizes lipopolysaccharide (LPS), heat-shock proteins, fibronectin, or specific virus envelope proteins[32]. In addition to PAMPs, TLRs also recognize danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) that originate from apoptotic cells[17].

TLRs are expressed in immune cells but also in epithelial cells and fibroblasts, and different TLR subtypes are expressed in divers cellular compartments[32]. Recognition of PAMPs by TLRs usually results in activation of an inflammatory pathway signaling cascade that initiates upregulation of genes encoding for inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and acute phase proteins[17,33]. While in principal, this response mechanism is indispensable for protection against pathogens, exaggerated or sustained activation may cause functional and morphological alterations (e.g., by apoptotic and pro-fibrotic pathways) and induce a compensatory reduction of immune system activity upon chronic activation (e.g., via IL-10 or soluble cytokine receptors), thus, promoting susceptibility to infections[33,34]. For example, chronic exposure to LPS can induce endotoxin tolerance by TLR4 dependent pathways, which is characterized by dampened antigen presentation, reduction of proinflammatory mediators and overexpression of anti-inflammatory signaling molecules[35].

Gut-liver crosstalk influences immune system homeostasis

The portal venous system transports nutrients and gut-derived signaling molecules as well as pathogens or PAMPs/DAMPs to the liver[36]. ACLD is associated with systemic proinflammatory changes that are clinically represented by elevated levels of C-reactive protein, inflammatory cytokines and immune cell activation markers[37,38]. Different hepatic cells interact by either producing or reacting to inflammatory cytokines. The equilibrium of pro-inflammatory vs anti-inflammatory cytokines may shift the course of disease towards progression or regeneration in patients with liver disease[39].

Systemic inflammation in patients with ACLD as compared to healthy subjects is considered to be caused by translocation of pathogens (or derived PAMPs and DAMPs) into the portal and systemic circulation via an impaired intestinal barrier, especially in the presence of intestinal dysbiosis[15]. The physiological slow blood flow in liver sinusoids enables a close and thorough interaction of gut-derived molecules with hepatic non-parenchymal and parenchymal cells, and importantly, with immune cells[40]. Fenestrations within the sinusoidal endothelium between liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs) facilitate extravasation of molecules and migration of immune cells[40]. Induction of the inflammasome (i.e., mediators of inflammatory response by upregulation of cytokines and caspases upon innate immune system recognition of PAMPs and DAMPs) through these mechanisms are associated with profibrotic and proinflammatory signaling cascades that putatively contribute to further aggravation of acute and chronic liver disease[41-43].

Hepatic immune cells “communicate” the presence of BT and liver injury to other cell types by activation of inflammatory and profibrotic pathways[44]. For instance, Kupffer cells, the liver-specific resident macrophages produce cytokines and chemotactic molecules in response to liver injury. As a result, additional monocyte-derived macrophages, but also natural killer and natural killer T cells are recruited to the liver[45]. Recognition of LPS by TLR4 on these macrophages and Kupffer cells results in activation of the NFκ-B-regulated inflammasome and increased Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) -α synthesis[46]. In the continuous presence of injury, DAMPs and/or PAMPs, these cells create a proinflammatory environment that finally facilitates hepatocyte injury and fibrosis via hepatic stellate cell activation, and even promotes tumor development[44,45].

For example, alcohol intake is associated with translocating PAMPs and microbiome changes that induce inflammatory signaling pathways in the liver and intestines[46-50]. Alcohol exposure also impacts on the expression profile of cytokines produced by intestinal immune cells (such as TNF-α and IL-1β) that impact both on liver disease and intestinal permeability[51,52].

Similarly, in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), PAMPs reach the liver via the portal venous circulation and induce tumor-necrosis-factor-dependent inflammatory pathways in the liver[15,53]. Intestinal dysbiosis was found to be more aggravated in NAFLD patients with advanced liver fibrosis, and metagenomic analysis achieved high accuracy in detecting advanced fibrosis in patients with NAFLD[54]. In another study, changes in microbiota composition were linked to the development of hepatic encephalopathy[55].

The significance of gut-liver crosstalk is further emphasized by studies that demonstrate a connection between HCC development and tumor progression to chronic hepatic inflammation caused by BT[56]. For example, TLR activation by LPS promotes not only fibrosis but also hepatocarcinogenesis[57,58], while blockade of the TLR4 signaling cascade reduces HCC formation[59,60]. Orci et al[61] recently investigated the role of TLR4-mediated pathways in HCC recurrence in mice that underwent temporary clamping of portal vessels to induce ischemic liver injury. The resulting obstruction of splanchnic blood flow resulted in increased BT and promotion of HCC recurrence through TLR4 signaling pathways. Importantly, ischemic preconditioning, intestinal decontamination and interference with TLR4 signaling impeded tumor recurrence. In summary, these observations point towards the connection between pathological changes in the intestines and ACLD.

FUNCTIONALITY OF THE INTESTINAL BARRIER AND THE ROLE OF BILE ACID SIGNALING

Intestinal barrier: Physiological and pathophysiological aspects

The intestinal barrier is composed of multiple components in different layers of the intestinal wall and functions as a highly specialized obstacle for translocation of gut-derived pathogens while allowing passage of nutrients, water, electrolytes, and hormones. Whereas the hydrophobic nature of cell membranes of epithelial cells prevents direct passage of most hydrophilic molecules, restriction of paracellular passage and mechanical integrity of the epithelium is ensured by - from apical to basal - tight junctions (TJ) (zonula occludens ZO), adherens junctions (AJ) (zonula adherens), and desmosomes (macula adherens)[62]. The main purpose of TJ lies in preventing paracellular translocation, while AJ and desmosomes primarily provide intercellular connection, thus causing proximity between epithelial cells that is vital for TJ formation[62]. In total, more than 50 proteins are involved in TJ formation. These proteins are usually subdivided into groups such as claudins, zonula occludens (ZO) proteins, and occludin.

Although claudin family members have similar properties, variation within certain regions cause differences in TJ charge selectivity and thus size and permeability of paracellular pores[63-66]. The interaction of TJ proteins is highly dynamic and the majority of proteins do not remain bound in a steady-state fashion and are rather subjected to constant exchange[67]. ZO-1 seems to be necessary for the binding interaction between occludin and the cytoskeleton at the TJ site[68]. Moreover, the close interaction between TJ and AJ proteins is further supported by the finding that trafficking of ZO-1 from the cytosol to the cell membrane depends on catenins, which are essential components of AJ[69]. In turn, cell adhesion by E-cadherin (i.e., an AJ component) is influenced by interaction of alpha-catenin with ZO-1[70].

The intestinal epithelium is additionally protected by a mucous layer that provides a physical barrier between bacteria and epithelial cells. The mucous layer mainly consists of mucins (glycoproteins) produced by goblet cells[71,72]. Additional host defense and protection of the epithelium is provided via secretion of antimicrobial peptides by Paneth cells[73].

Importantly, bacteria that are entering the bloodstream are not only required to migrate across the epithelial barrier but also the vascular barrier that also contains TJ and AJ. The bacterium Salmonella typhimurium, for example, can penetrate the vascular barrier by interfering with Wnt/β-catenin signaling that regulates AJ functionality via E-cadherin/β-catenin[74,75]. Importantly, hepatitis B virus also interferes with Wnt/β-catenin signaling[76].

Considering the knowledge on the complex systems regulating intestinal permeability, it is imperative for translational research to explore alterations of mucosal barrier function in ACLD (Figure 1). In this regard, it was found that alcohol exposure decreases expression levels of TJ proteins[77,78]. Certain detrimental effects of alcohol on the intestinal barrier can be attributed to its metabolite acetaldehyde, which dysregulates protein phosphatases and kinases that ensure TJ and AJ integrity between intestinal epithelial cells[79-83]. Additionally, decreased production of antimicrobial peptides by Paneth cells was found to be associated with BT in cirrhotic animals[84]. The finding that the inflammation marker IL-6 increases TJ permeability for small molecules via upregulation of the claudin-2 gene does not give a rationale for BT caused by IL-6 but may suggest that a pro-inflammatory state during liver disease also impacts on gut permeability[85]. In contrast, the inflammatory cytokines interferon-γ and TNF-α have been shown to increase gut permeability by downregulation of TJ proteins[86-89].

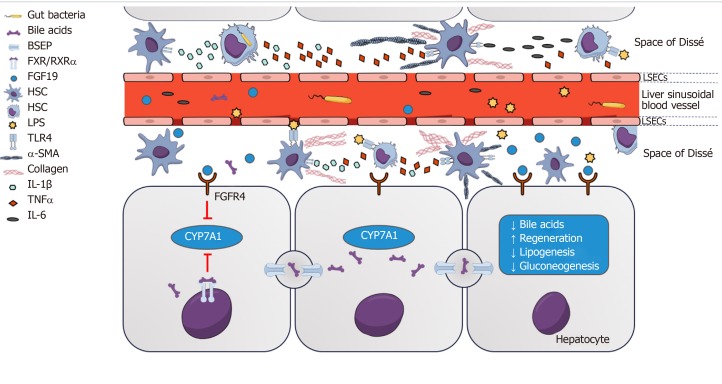

Figure 1.

Farnesoid X receptor-fibroblast growth factor 19 signaling between gut and liver regulates bile acid homeostasis and impacts on mucosal barrier function. Bacterial translocation triggers fibrosis and hepatic inflammation via activation of hepatic stellate cells and liver-resident macrophages. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 19 binds to FGF receptor 4 on hepatocytes which subsequently suppresses the expression of CYP7A1. FGF19 is upregulated postprandially and influences farnesoid X receptor-dependent metabolic pathways involved in gluconeogenesis, protein synthesis, insulin sensitivity and lipid profile. Kupffer cells and monocyte-derived macrophages produce cytokines and chemotactic molecules in response to liver injury. Recognition of lipopolysaccharide by Toll-like receptor 4 on macrophages and Kupffer cells results in activation of the NFκ-B-regulated inflammasome and increases tumor necrosis factor-α synthesis. In the continuous presence of injury, pathogen-associated molecular patterns and/or danger-associated molecular patterns, these cells create a proinflammatory environment that finally cause hepatocyte injury and fibrosis via hepatic stellate cell stimulation that results in production of collagen and α-smooth muscle actin. FXR: Farnesoid X receptor; RXRα: Retinoid X receptor; BSEP: Bile salt export pump; FGF: Fibroblast growth factor; FGFR4: Fibroblast growth factor receptor 4; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; α-SMA: α smooth muscle actin; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; IL: Interleukin; HSC: Hepatic stellate cell; LSEC: Liver sinusoidal endothelial cell; TLR: Toll-like receptor; PAMPs: Pathogen-associated molecular patterns; α-SMA: α-smooth muscle actin.

Some pharmacological agents that are currently tested for the treatment of liver disease were shown to effect the expression profile of certain TJ proteins in the gut epithelium[90,91], which gives a clinical and therapeutic perspective that will be summarized in another chapter of this review.

Intestinal permeability is linked to portal hypertension

In the setting of PHT, the elevated plasma volume and increased intravascular pressure in splanchnic vessels influence not only vascular but also intestinal permeability[92]. Again, a potential pathophysiological mechanism that links PHT to BT lies in the congestion of the blood flow in the portal vein back to intestinal mucosal microcirculation. Chronic exposure to elevated portal pressure impairs microcirculation, promotes neoangiogenesis, and increases permeability in the splanchnic vasculature[12,93]. Ultimately, these vascular changes also affect intestinal barrier function.

An experimental study comparing two rat models of PHT, partial portal vein ligation (PPVL) and common bile duct ligation (BDL), demonstrated that angiogenesis in the splanchnic vessels is increased in both models[94]. Similarly, vascular endothelial growth factor and endothelial nitric oxide synthase were elevated in PPVL and BDL rats. Conversely, microvascular leakage of macromolecules was only observed in the BDL model, indicating that liver damage and/or cholestasis further aggravate the disrupted homeostasis of neovascularization and vessel integrity[94].

In an exploratory human study, patients with PHT had increased dilatation of intercellular spaces in the jejunum as compared to healthy controls[95], as well as increased spaces between duodenal enterocytes and shortening and decreased density of microvilli[96]. Furthermore, patients with PHT had increased vessel diameters within the jejunal and duodenal mucosa, edema within the subepithelial lamina propria, as well as a decline of villous/crypt ratio[97]. However, these and other studies in humans are often limited by small sample sizes and insufficient patient characterization of by means of etiology, HVPG, and liver disease stage. Still, there are several studies in patients with portal hypertensive gastropathy that indicate increased gastrointestinal permeability[93,98-100].

The finding that soluble CD163 (sCD163) correlates with the HVPG has provided a biomarker-derived link between the immune system and PHT[101]. For example, together with serum fibrosis markers, sCD163 can predict CSPH with very high accuracy[102]. The protein CD163 functions as a hemoglobin-haptoglobin scavenger receptor and represents activation of Kupffer cells and macrophages as it is released into the circulatory blood system upon TLR activation[103,104]. sCD163 levels were found to be significantly higher in the hepatic vein as compared to the portal vein, supporting that liver-resident immune cells are indeed a significant source of elevated sCD163 serum concentrations[105].

Interestingly, patients receiving transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting (TIPS) to reduce portal pressure had a post-interventional decline of LPS-binding protein (LBP), whereas sCD163 concentrations remained unchanged[105]. Similarly, markers of inflammation decline after TIPS implantation but remain independent predictors of death, raising the question whether systemic inflammation and the role of BT remain important factors in the course of disease in some patients, even when the severity of PHT is successfully reduced by established treatment strategies[106,107]. In addition, this observation reveals the uncertainty which factors contributing to progression or regression of disease remain or become relevant after etiological treatment of liver disease. Recent findings in animal models of cirrhosis indicate that extrahepatic vascular changes (such as angiogenesis, shunting and increased splanchnic blood flow) persist and may represent an important cause of impaired regression of PHT[108,109]. Based on the findings of this study, it may also be speculated that structural changes disturbing the gut barrier function persist, despite a substantial reduction in intrahepatic resistance/portal pressure by etiological treatments or TIPS. In the study of Holland-Fischer et al[105], however, LBP levels of patients almost normalized after receiving TIPS.

Bile acids: Communicators between liver and gut in health and disease

The microbiome composition is considered to impact on the intestinal barrier integrity during liver disease and unfavorable shifts towards pathogenic bacteria have been found in both experimental and clinical studies, as extensively reviewed by others[13,15,54].

In an animal model of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), Klebsiella pneumoniae induced pore formation in the epithelial layer, as well as priming of T-cells in the liver that lead to aggravation of hepatobiliary damage. In this study, the synergistic effect of multiple pathobionts was also suggested, which seems to be the most likely scenario in human disease[110]. In turn, the microbiota composition depends on the level and hydrophilicity of intestinal bile acids that likely represent another important link between liver disease and gut barrier integrity[111]. Multidrug resistance protein 2 knockout mice (i.e., an animal model for PSC) underwent significant changes in microbiota and serum BA composition. Interestingly, microbiota transfer to wild type mice led to liver injury which was associated with activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in both liver and intestines[112].

BAs both exert direct effects on bacterial dysbiosis and adhesion through interaction with microbial membrane lipids and proteins that cause changes in membrane integrity, leakage, and cell death[113-119]. BAs undergo enterohepatic circulation, which is characterized by secretion, reabsorption and recycling of primary and secondary BAs[15]. Primary BAs are produced from cholesterol in hepatocytes and are secreted into the bile duct. Most BAs (about 95%) are reabsorbed in the terminal ileum via active transport mechanisms, transported back to the liver in the portal venous system and recycled by hepatocytes[120]. Conversely, a small percentage of BAs is metabolized by intestinal bacteria. These so-called secondary BAs are passively absorbed into the systemic circulation[15,121].

In physiological conditions (“neutral” pathway), cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (CYP7A1) is the most important rate-limiting enzyme for primary BA synthesis. Alternative pathways (“acidic” pathways) to synthesize BAs, including mitochondrial sterol 27 hydroxylase (CYP27A1) and sterol 12α-hydroxylase (CYP8B1), are only responsible for a minority of BA synthesis in healthy humans. However, this equilibrium shifts towards the acidic pathways in patients with liver disease[122,123]. Importantly, these bile acids have slightly different chemical properties. The resulting differences of bile acid composition in liver disease were linked to intestinal barrier dysfunction and permeability[122,124,125]. Additionally, LPS was found to significantly suppress the expression of CYP7A1 in the liver. These findings suggest that dysregulated BA homeostasis participates in a vicious circle towards an impaired gut barrier function[126].

Farnesoid X receptor activation affects intestinal barrier integrity

BAs also exert direct effects on gut barrier integrity through activation of the nuclear bile acid receptor (farnesoid X receptor, FXR) in the intestinal epithelium[111,127]. FXR belongs to the group of non-steroidal nuclear receptors and acts as a transcription factor through binding to hormone response elements upon activation. Similar to other receptors in this family, DNA binding requires heterodimer formation with retinoic acid receptor α (RXRα)[128]. FXR is expressed both in liver and gut, with highest expression levels located in the ileum[129]. More precisely, FXR is located in the epithelium, while there is little or no expression in layers beneath, such as lamina propria and tunica muscularis[127]. Decreased intestinal BA availability in cholestatic animal models is associated with increased BT and endotoxemia. Conversely, concomitant oral administration of BAs has beneficial effects on BT[130,131]. Importantly, FXR activation leads to upregulation of genes associated with intestinal protection, gut barrier integrity, and amelioration of dysbiosis[127]. Administration of pharmacological FXR agonists was found to ameliorate the microbiota profile, increase antimicrobial peptides and expression of tight junction proteins, and finally, reduce BT[91].

In mice, FXR activation in enterocytes located in the ileum upregulates the expression of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 15, the murine analogue of human FGF19, via binding to response elements for the FGF15/19 gene[132,133]. Importantly, binding to the FGF19 gene response element relies on heterodimer formation with RXRα[134]. FGF15/19 is subsequently secreted into the portal venous blood system and functions as a hormone of gut-liver signaling[132,133]. FGF19 binds to FGF receptor 4 located on hepatocytes and reduces BA synthesis by suppressing the expression of CYP7A1[134].

Interestingly, short-term suppression of CYP7A1 is rather dependent on intestinal than hepatic FXR activation[135]. This pathway seems to be independent from FXR-induced expression of small heterodimer partner 1 that also suppresses CYP7A1 via liver receptor homolog 1[136], suggesting two major mechanisms of FXR-dependent BA feedback that are independent from each other[134]. Furthermore, FGF19 is postprandially upregulated and influences FXR-dependent pathways involved in gluconeogenesis, protein synthesis, insulin sensitivity, and lipid metabolism[133,134,137]. Recent findings indicate that FGF19-induced phosphorylation of FXR is critical for heterodimerization with RXRα, migration to the nucleus, and DNA binding– a mechanism that is impaired in patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC)[138]. This is in accordance with the finding that FGF19 is upregulated in PBC patients and correlates with disease severity[139]. Along with the effects of FXR activation on the expression of proteins involved in the formation of the intestinal barrier, these findings indicate clinical relevance of FXR-FGF19 feedback mechanisms.

Addressing the “chicken vs egg” dilemma

The data on BT and its impact on hepatic and systemic inflammation vs splanchnic neoangiogenesis and vasodilation caused by PHT reveals the “chicken vs egg” dilemma concerning the gut-liver axis concept: It currently remains elusive if microbiota changes and BT are primarily caused by PHT or if the presence of PHT and its severity are rather a result of BT. It seems likely that there exists bidirectional influence, however, clinical studies usually fail to separate whether BT is the main cause for disease progression or is in turn the result of liver injury and PHT. However, studies on genetic variants that facilitate BT might provide important insights in this conundrum. Impact of genetic polymorphisms that impact on signaling pathways involved in intestinal barrier or BT do not leave us with the question “cause or consequence of disease progression” since this particular genetic condition is inherently present in affected patients.

For example, it was found that patients with a genetic variant of the nuclear dot protein 52 kDa (NDP52; regulates TLR signaling pathways) gene[140] or TLR2 variants had an increased risk for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP)[141]. Similarly, Nucleotide-Binding Oligomerization Domain-Containing Protein 2 (NOD2) variants were associated with an increased risk of developing SBP and mortality[142,143]. NOD2 recognizes intracellular peptidoglycan fragments of bacteria and induces formation of autophagosomes as well as host-defense mechanisms such as cytokines and antimicrobial peptides[144]. Patients carrying NOD2 variants had increased markers of intestinal permeability and inflammation[93,145]. Interestingly, Reichert et al[146] recently showed that NOD2 variants as well as CSPH are independently associated with bacterial infections in compensated cirrhosis. In contrast, only CSPH - and not NOD2 variants - remained an independent risk factor for infection in decompensated patients.

FXR polymorphisms in humans have been shown to either promote or protect against hepatic decompensation. For example, the rs56163822 G/T polymorphism was significantly more prevalent in patients developing SBP[147]. This specific polymorphism is associated with decreased translation of FXR and reduced transcriptional activity of target genes[148,149]. In contrast, patients with the FXR-SNP rs35724 minor allele (i.e., FXR gain of function mutation) were less likely to develop ascites or liver-related death[150].

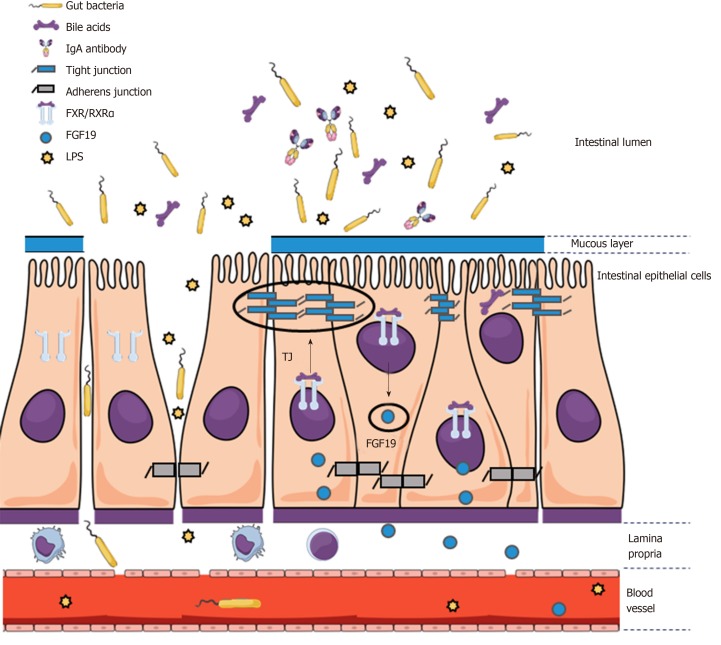

Interestingly, Sorribas et al[151] recently found that the gut-vascular and mucosal epithelial barriers were profoundly impaired in cirrhotic mice (induced by BDL or carbontetrachloride administration, CCl4) while this effect was not present, or at least significantly less pronounced, in portal-hypertensive mice without cirrhosis (PPVL). Importantly, it was observed that these barriers were regulated by FXR-dependent mechanisms (Figure 2) and BT was reduced upon treatment with FXR agonists[151].

Figure 2.

An impaired mucosal epithelial barrier integrity facilitates bacterial translocation and is regulated by farnesoid X receptor-dependent mechanisms. Increased systemic inflammation in cirrhotic patients as compared to healthy subjects is considered to be associated with intestinal dysbiosis leading to translocation of pathogens- or derived pathogen-associated molecular patterns and danger-associated molecular patterns into the portal circulation, which is further facilitated by an impaired intestinal barrier. Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) activation in ileum enhances the expression of fibroblast growth factor 15 (mice) or 19 (humans) via binding to response elements in the nucleus. FXR activation leads to upregulation of tight junction proteins and decrease of bacterial translocation. FXR: Farnesoid X receptor; IgA: Immunoglobulin A; RXRα: Retinoid X receptor; FGF: Fibroblast growth factor; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; TJ: Tight junction.

These experimental data are highly relevant for the “chicken vs egg” debate because they suggest that PHT itself has only a minor impact on barrier integrity, while it also explicitly considers that the muco-epithelial and gut-vascular barrier are different entities. Along with observations from genetic studies that suggest that BT and inflammation do not only result from decompensation but rather are drivers of (further) hepatic decompensation, efforts towards elucidating this conundrum have the potential to identify therapeutic approaches in patients with cirrhosis and PHT.

THERAPEUTIC STRATEGIES TARGETING THE GUT-LIVER AXIS

Importantly, the identification and targeting of potentially reversible causes of liver injury and their elimination will always remain the main management priority in patients with chronic liver disease. In ALD, the most common cause of cirrhosis in Europe[4], alcohol abstinence improves PHT[152] and the prognosis of patients in both early and advanced stages of cirrhosis[153,154]. Similarly, weight loss in NASH patients was linked to fibrosis regression and NASH resolution[155], and elimination of hepatitis C virus by direct antiviral agents results in reduction of PHT and HCC risk[156-159].

As depicted above, PHT impacts on the course of cirrhosis by promoting hepatic decompensation and ACLF, hemodynamic dysregulation as well as intestinal permeability and BT. In turn, PHT is aggravated by hyperdynamic circulation and also proinflammatory and profibrotic stimuli caused by BT. This reciprocal influence contributes to further aggravation of the disease and also promotes carcinogenesis, which has been shown in different etiologies of liver disease[14,17,41,160,161]. Thus, evidence-based therapeutic options to positively influence or ideally break the vicious circle of a dysregulated gut-liver axis in cirrhosis are urgently needed. Consequently, therapeutic approaches that target PHT, intestinal permeability, and the microbiome composition may be all viable future therapeutic options for improving prognosis and risk of further disease aggravation. Importantly, some of these therapeutic approaches are currently being investigated in clinical trials in humans[160].

Reduction of portal hypertension: Non-selective beta-blockers

According to current treatment guidelines, NSBB are used for pharmacological reduction of PHT in patients with cirrhosis[1,162]. The treatment rationale of NSBB is primarily based on beneficial effects towards prevention of decompensation such as variceal bleeding[21,163,164]. Additionally, cirrhotic patients under NSBB treatment presenting with ACLF were found to have lower grades of liver failure as well as better chances of short-term (but not long-term) survival as compared to patients not receiving NSBB treatment, which was accompanied by lower white blood cell counts[165]. Of note, in this study patients were not randomized to receive NSBB treatment and the decision process on treatment initiation or discontinuation was not assessed[165]. Importantly, based on animal data indicating beneficial effects on BT[166] it was found that markers of intestinal permeability and BT decreased upon NSBB treatment in patients with cirrhosis[93]. This effect was also observed in patients without significant reduction of HVPG by NSBB treatment (“non-responders”), suggesting that even hemodynamic non-responders may benefit from continuation of NSBB treatment[93].

Targeting the microbiome and bacterial translocation: Antibiotics, probiotics and the role of proton pump inhibitors

Current guidelines recommend continuous prophylaxis with antibiotics for patients with cirrhosis either at particularly high risk of or after SBP[7]. Primary prophylaxis with norfloxacin significantly reduces the incidence of infections, however, it is not entirely clear by now which patients with ascites actually have survival benefits upon primary prophylaxis[167,168]. Patients with genetic variants that increase susceptibility for developing infections may represent an interesting target population for antibiotic prophylaxis. The currently ongoing INCA trial (EudraCT 2013-001626-26) will hopefully provide data on the efficacy of primary prophylaxis in patients with NOD2 risk variants[169].

Survival benefits and decreased risk of AD and ACLF were found upon antibiotic treatment at the occurrence of variceal bleeding[7]. Currently, fluoroquinolones (such as norfloxacin and ciprofloxacin) and third generation cephalosporins are recommended first line antibiotic regimens to be used in acute variceal bleeding[7] in order to prevent infections.

Moreover, the portal pressure-lowing effect of norfloxacin has been investigated. A small randomized controlled trial (RCT) with a cross-over design assessed the effect of 4-wk therapy with norfloxacin and did not result in significant reduction of portal pressure. However, sample size was limited and considerable changes in HVPG during placebo treatment were observed[170]. Another RCT investigating the effect of 4-wk norfloxacin therapy on hemodynamics found that patients with cirrhosis had a reduction of serum LPS and higher mean arterial pressure, while there was a trend towards a reduction of cardiac output and HVPG. Although the trial was limited by a small sample size, these observations might indicate that inducing changes in microbiota composition influences BT and positively influences hyperdynamic circulation in patients with cirrhosis[171].

Moreover, non-absorbable antibiotics such as rifaximin are currently used for the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. However, there is conflicting data on the efficacy towards BT, systemic inflammation and hemodynamics: Some studies present significant beneficial effects on systemic inflammation and hemodynamics[172,173], while another RCT found no or only small benefits by rifaximin treatment[174,175]. The results of currently ongoing trials on rifaximin will hopefully provide further insight into treatment efficacy and the role of treatment-induced microbiome changes in cirrhosis[176].

Probiotics, i.e., bacteria that modify microbiome composition and mucosal integrity by suppression of pathogenic bacteria, are currently studied extensively. However, there is conflicting data on the efficacy of probiotics, which has been extensively reviewed by Wiest et al[160]. The authors summarize that positive effects of probiotics are greatly dependent on host genetic properties, individual diet and microbiome composition.

Lastly, awareness towards prudent use of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) in patients with cirrhosis should be encouraged: PPI intake has been repeatedly found to be associated with increased risk of developing hepatic encephalopathy and infections, such as SBP[177-179]. Interestingly, PPIs induce both significant change of the microbiome composition as well as bacterial metabolism in patients with compensated cirrhosis[180]. Although the data may not prove causality between PPI intake and BT, cautious prescription of PPIs in patients with cirrhosis is warranted.

Mediating gut-liver-crosstalk: FXR-directed therapies

BA-associated signaling in the gut and the liver plays a major role in the gut-liver axis. Many effects are mediated via binding of BA to the nuclear receptor FXR[181]. Therefore, several pharmacological compounds targeting FXR have emerged in the last years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Farnesoid X receptor-targeting therapies in liver disease: Experimental vs clinical evidence

| Location | Target | Experimental evidence | Clinical evidence |

| Liver | Metabolism and inflammation | OCA/NASH/mouse: Decreased hepatocyte apoptosis and less fibrosis; similar steatosis[194] OCA/NASH/hamster: Higher LDL and lower HDL[195] OCA/NAFLD/rabbit: Decreased steatosis, inflammation, insulin resistance and improved lipid profile[196] | OCA/NASH/NCT01265498: Improved histological features; 20% pruritus, impaired lipid profile[183] OCA/PBC/NCT01473524: Improved biochemical laboratory values; frequent pruritus[184,185] OCA/PSC/NCT02177136: Completed; statistical results pending; PEP: Change of ALP levels as compared to BL |

| Fibrosis and portal hypertension | PX20606/CCl4/rat: Reduced fibrosis, PP, and sinusoidal remodeling[192] OCA/TAA/rat: Reduced fibrosis, PP, hepatic inflammation[182] | OCA/NASH/NCT02548351: Recruiting; PEP: 1 stage of liver fibrosis improvement; NASH resolution OCA/PBC/NCT02308111: Recruiting; PEP: Death, OLT; MELD ≥ 15; decompensation NGM282/PSC/NCT02704364: reduced fibrosis biomarkers[193] OCA/ALD/PESTO: PEP: Lower HVPG after 7 d of treatment by 15% or more, or HVPG < 12 mmHg[188] | |

| Gut | Microbiome | OCA/Healthy/mouse: Lower endogenous BA levels; elevated Firmicutes in small intestine[197] Fexaramine/NAFLD/mouse: Microbiome changes induce different BA profile; GLP-1 signaling improves insulin sensitivity[198] | OCA/Healthy/NCT01933503: Reversible changes in gram-positive bacterial strains[197] |

| Intestinal barrier | OCA/BDL/rat: Upregulation of TJ proteins, decrease of intestinal inflammation and BT[90] OCA/CCl4/rat: Upregulation of antimicrobial peptides, TJ proteins; reduced BT and liver fibrosis[91] GW4064/BDL/mouse: Upregulation of enteroprotective genes and improvement of barrier function[127] Fexaramine/ALD/mouse: Improvement of intestinal barrier, lipid metabolism and alcohol-induced liver injury[190] OCA + Fexaramine/PPVL + BDL + CCl4/mouse: reduction of BT; OCA: Improvement of muco-epithelial and gut-vascular barrier; Fexaramine: Improvement of muco-epithelial but no effect on gut-vascular barrier[151] | No human data available | |

| Metabolism/inflammation | Fexaramine/NAFLD/mouse: Amelioration of metabolic syndrome, induction of FGF15, decreased insulin resistance[189] OCA/IBD/mouse: Decreased intestinal inflammation and permeability[191] | No human data available |

OCA: Obeticholic acid; NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; LDL: Low density lipoprotein; HDL: High density lipoprotein; NAFLD: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NCT: National clinical trial identifier; PEP: Primary efficacy endpoint; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; BL: Baseline; CCl4: Carbon tetrachloride; PP: Portal pressure; TAA: Thioacetamide; OLT: Orthotopic liver transplantation; MELD: Model for end-stage liver disease; ALD: Alcoholic liver disease; HVPG: Hepatic venous pressure gradient; BA: Bile acid; GLP-1: Glucagon like peptide 1; TJ: Tight junction; BT: Bacterial translocation; BDL: Bile duct ligation; FGF15: Fibroblast growth factor 15; IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease.

Treatment with the FXR agonist obeticholic acid (OCA) upregulates expression of tight junction proteins (e.g., ZO-1, occludin and claudin-1/2), antimicrobial molecules (e.g., angiogenin-1 and alpha-5-defensin) and reduces BT and intestinal inflammation in cirrhotic rats[90,91,127]. Similarly, activation of hepatic inflammatory pathways and fibrogenesis were reduced in animals upon OCA treatment[182]. OCA has primarily been tested in clinical trials including patients with PBC and NASH. The FLINT RCT in non-cirrhotic NASH patients indicated that OCA improves histological features of the disease, however, pruritus seems to be an inconvenient side effect that was reported by approximately one fifth of patients[183]. Furthermore, unfavorable changes in the lipid profile (increase of total and LDL cholesterol) were observed upon OCA treatment[183]. In two RCTs in PBC patients, OCA improved serum levels of transaminases and bilirubin, however, side effects like pruritus were also more frequent in the treatment groups as compared to placebo[184,185]. Another safety issue towards treatment with FXR-activators was raised by an animal study indicating that overexpression of FGF19 is associated with HCC[186]. Further study results of trials investigating OCA treatment in NASH (REGENERATE; NCT02548351), ALD (TREAT; NCT02039219), and PSC (AESOP; NCT02177136) are pending. Recent presentation of an interim analysis of the REGENERATE trial revealed dose-dependent positive effects of OCA on liver fibrosis, steatohepatitis and serum parameters associated with liver damage[187]. Importantly, short-term treatment with the steroidal FXR agonist OCA in cirrhotic patients with PHT (PESTO trial) has shown promising results in regard to a significant reduction of HVPG[188].

Newly emerging, non-steroidal FXR-agonists might be associated with an improved side effect profile as compared to OCA and showed promising results in metabolic liver disease[160]. Treatment with the non-absorbable FXR agonist fexaramine that only affects intestinal FXR has shown positive results towards steatosis and glucose homeostasis in animals and may represent an elegant solution for intestinal FXR targeting with a favorable side effect profile[189]. Fexaramine was also associated with improvement of the intestinal barrier, lipid metabolism and alcohol-induced liver injury[190]. Experimental data in the field of inflammatory bowel disease shows a decrease of proinflammatory cytokines by intestinal immune cells that are associated with increased gut permeability upon FXR activation[191]. In cirrhotic animals, a non-steroidal FXR-agonist reduced PHT, BT and vascular remodeling[192]. The non-tumorigenic FGF19 analogue NGM282 was associated with reduced fibrosis biomarkers in a phase II trial in humans with PSC, indicating an amelioration of fibrosis which may also be accompanied by an amelioration of PHT. However, histological and hemodynamic data were not obtained within this study[193].

Taken together, therapeutics that target FXR are likely to have beneficial effects on the gut-liver axis in cirrhosis, provided that potential side effects will be successfully minimized by recent efforts to find even more suitable compounds.

CONCLUSION

In ACLD, PHT results from increased intrahepatic resistance and leads to splanchnic vasodilation and neovascularization in the intestines. Gut dysbiosis, increased intestinal permeability, translocation of bacteria and PAMPs can further promote liver disease progression, often mediated via immune system activation and a subsequent induction of a proinflammatory state. The close relationship between gut and liver and their bidirectional interaction during liver disease has been termed gut-liver axis. Treatment strategies targeting the gut-liver axis via amelioration of PHT, microbiota composition, and intestinal barrier integrity are supposed to exert beneficial effects. However, further studies in humans will be needed to assess efficacy and safety of different FXR agonists and other gut-liver axis-oriented therapies in different clinical settings. In general, further insight into the pathophysiology involved in the “chicken and the egg” dilemma may reveal important novel targets that inhibit liver disease progression or promote disease regression after etiological treatment. While this review aims to comprehensively summarize the current state of knowledge obtained by experimental and clinical studies, it is designed as a narrative review. Thus, the possibility of selection bias and underreporting of negative studies represents a potential limitation of this review.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Figures were created by including images from the Mind the Graph platform, available at www.mindthegraph.com.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: No financial support has been received for this review. Benedikt Simbrunner has received travel support from AbbVie and Gilead; Mattias Mandorfer has served as a speaker and/or consultant and/or advisory board member for AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, W.L. Gore & Associates and Janssen; Michael Trauner received speaker fees from BMS, Falk Foundation, Gilead and MSD; advisory board fees from Albireo, Falk Pharma GmbH, Genfit, Gilead, Intercept, MSD, Novartis, Phenex and Regulus. He further received travel grants from Abbvie, Falk, Gilead and Intercept and unrestricted research grants from Albireo, Cymabay, Falk, Gilead, Intercept, MSD and Takeda. Thomas Reiberger received grant support from Abbvie, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Gilead, MSD, Philips Healthcare, Gore; speaking honoraria from Abbvie, Gilead, Gore, Intercept, Roche, MSD; consulting/advisory board fee from Abbvie, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Gilead, MSD, Siemens; and travel support from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Gilead and Roche.

Peer-review started: June 4, 2019

First decision: July 21, 2019

Article in press: September 27, 2019

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Austria

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Abid S, Orci LA, Russo E S-Editor: Tang JZ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Benedikt Simbrunner, Department of Internal Medicine III, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna 1180, Austria; Vienna Hepatic Hemodynamic Lab, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna 1180, Austria.

Mattias Mandorfer, Department of Internal Medicine III, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna 1180, Austria; Vienna Hepatic Hemodynamic Lab, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna 1180, Austria.

Michael Trauner, Department of Internal Medicine III, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna 1180, Austria.

Thomas Reiberger, Department of Internal Medicine III, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna 1180, Austria. thomas.reiberger@meduniwien.ac.at; Vienna Hepatic Hemodynamic Lab, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna 1180, Austria.

References

- 1.de Franchis R, Baveno VI Faculty. Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: Report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: Stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2015;63:743–752. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2013 DALYs and HALE Collaborators, Murray CJ, Barber RM, Foreman KJ, Abbasoglu Ozgoren A, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Aboyans V, Abraham JP, Abubakar I, Abu-Raddad LJ, Abu-Rmeileh NM, Achoki T, Ackerman IN, Ademi Z, Adou AK, Adsuar JC, Afshin A, Agardh EE, Alam SS, Alasfoor D, Albittar MI, Alegretti MA, Alemu ZA, Alfonso-Cristancho R, Alhabib S, Ali R, Alla F, Allebeck P, Almazroa MA, Alsharif U, Alvarez E, Alvis-Guzman N, Amare AT, Ameh EA, Amini H, Ammar W, Anderson HR, Anderson BO, Antonio CA, Anwari P, Arnlöv J, Arsic Arsenijevic VS, Artaman A, Asghar RJ, Assadi R, Atkins LS, Avila MA, Awuah B, Bachman VF, Badawi A, Bahit MC, Balakrishnan K, Banerjee A, Barker-Collo SL, Barquera S, Barregard L, Barrero LH, Basu A, Basu S, Basulaiman MO, Beardsley J, Bedi N, Beghi E, Bekele T, Bell ML, Benjet C, Bennett DA, Bensenor IM, Benzian H, Bernabé E, Bertozzi-Villa A, Beyene TJ, Bhala N, Bhalla A, Bhutta ZA, Bienhoff K, Bikbov B, Biryukov S, Blore JD, Blosser CD, Blyth FM, Bohensky MA, Bolliger IW, Bora Başara B, Bornstein NM, Bose D, Boufous S, Bourne RR, Boyers LN, Brainin M, Brayne CE, Brazinova A, Breitborde NJ, Brenner H, Briggs AD, Brooks PM, Brown JC, Brugha TS, Buchbinder R, Buckle GC, Budke CM, Bulchis A, Bulloch AG, Campos-Nonato IR, Carabin H, Carapetis JR, Cárdenas R, Carpenter DO, Caso V, Castañeda-Orjuela CA, Castro RE, Catalá-López F, Cavalleri F, Çavlin A, Chadha VK, Chang JC, Charlson FJ, Chen H, Chen W, Chiang PP, Chimed-Ochir O, Chowdhury R, Christensen H, Christophi CA, Cirillo M, Coates MM, Coffeng LE, Coggeshall MS, Colistro V, Colquhoun SM, Cooke GS, Cooper C, Cooper LT, Coppola LM, Cortinovis M, Criqui MH, Crump JA, Cuevas-Nasu L, Danawi H, Dandona L, Dandona R, Dansereau E, Dargan PI, Davey G, Davis A, Davitoiu DV, Dayama A, De Leo D, Degenhardt L, Del Pozo-Cruz B, Dellavalle RP, Deribe K, Derrett S, Des Jarlais DC, Dessalegn M, Dharmaratne SD, Dherani MK, Diaz-Torné C, Dicker D, Ding EL, Dokova K, Dorsey ER, Driscoll TR, Duan L, Duber HC, Ebel BE, Edmond KM, Elshrek YM, Endres M, Ermakov SP, Erskine HE, Eshrati B, Esteghamati A, Estep K, Faraon EJ, Farzadfar F, Fay DF, Feigin VL, Felson DT, Fereshtehnejad SM, Fernandes JG, Ferrari AJ, Fitzmaurice C, Flaxman AD, Fleming TD, Foigt N, Forouzanfar MH, Fowkes FG, Paleo UF, Franklin RC, Fürst T, Gabbe B, Gaffikin L, Gankpé FG, Geleijnse JM, Gessner BD, Gething P, Gibney KB, Giroud M, Giussani G, Gomez Dantes H, Gona P, González-Medina D, Gosselin RA, Gotay CC, Goto A, Gouda HN, Graetz N, Gugnani HC, Gupta R, Gupta R, Gutiérrez RA, Haagsma J, Hafezi-Nejad N, Hagan H, Halasa YA, Hamadeh RR, Hamavid H, Hammami M, Hancock J, Hankey GJ, Hansen GM, Hao Y, Harb HL, Haro JM, Havmoeller R, Hay SI, Hay RJ, Heredia-Pi IB, Heuton KR, Heydarpour P, Higashi H, Hijar M, Hoek HW, Hoffman HJ, Hosgood HD, Hossain M, Hotez PJ, Hoy DG, Hsairi M, Hu G, Huang C, Huang JJ, Husseini A, Huynh C, Iannarone ML, Iburg KM, Innos K, Inoue M, Islami F, Jacobsen KH, Jarvis DL, Jassal SK, Jee SH, Jeemon P, Jensen PN, Jha V, Jiang G, Jiang Y, Jonas JB, Juel K, Kan H, Karch A, Karema CK, Karimkhani C, Karthikeyan G, Kassebaum NJ, Kaul A, Kawakami N, Kazanjan K, Kemp AH, Kengne AP, Keren A, Khader YS, Khalifa SE, Khan EA, Khan G, Khang YH, Kieling C, Kim D, Kim S, Kim Y, Kinfu Y, Kinge JM, Kivipelto M, Knibbs LD, Knudsen AK, Kokubo Y, Kosen S, Krishnaswami S, Kuate Defo B, Kucuk Bicer B, Kuipers EJ, Kulkarni C, Kulkarni VS, Kumar GA, Kyu HH, Lai T, Lalloo R, Lallukka T, Lam H, Lan Q, Lansingh VC, Larsson A, Lawrynowicz AE, Leasher JL, Leigh J, Leung R, Levitz CE, Li B, Li Y, Li Y, Lim SS, Lind M, Lipshultz SE, Liu S, Liu Y, Lloyd BK, Lofgren KT, Logroscino G, Looker KJ, Lortet-Tieulent J, Lotufo PA, Lozano R, Lucas RM, Lunevicius R, Lyons RA, Ma S, Macintyre MF, Mackay MT, Majdan M, Malekzadeh R, Marcenes W, Margolis DJ, Margono C, Marzan MB, Masci JR, Mashal MT, Matzopoulos R, Mayosi BM, Mazorodze TT, Mcgill NW, Mcgrath JJ, Mckee M, Mclain A, Meaney PA, Medina C, Mehndiratta MM, Mekonnen W, Melaku YA, Meltzer M, Memish ZA, Mensah GA, Meretoja A, Mhimbira FA, Micha R, Miller TR, Mills EJ, Mitchell PB, Mock CN, Mohamed Ibrahim N, Mohammad KA, Mokdad AH, Mola GL, Monasta L, Montañez Hernandez JC, Montico M, Montine TJ, Mooney MD, Moore AR, Moradi-Lakeh M, Moran AE, Mori R, Moschandreas J, Moturi WN, Moyer ML, Mozaffarian D, Msemburi WT, Mueller UO, Mukaigawara M, Mullany EC, Murdoch ME, Murray J, Murthy KS, Naghavi M, Naheed A, Naidoo KS, Naldi L, Nand D, Nangia V, Narayan KM, Nejjari C, Neupane SP, Newton CR, Ng M, Ngalesoni FN, Nguyen G, Nisar MI, Nolte S, Norheim OF, Norman RE, Norrving B, Nyakarahuka L, Oh IH, Ohkubo T, Ohno SL, Olusanya BO, Opio JN, Ortblad K, Ortiz A, Pain AW, Pandian JD, Panelo CI, Papachristou C, Park EK, Park JH, Patten SB, Patton GC, Paul VK, Pavlin BI, Pearce N, Pereira DM, Perez-Padilla R, Perez-Ruiz F, Perico N, Pervaiz A, Pesudovs K, Peterson CB, Petzold M, Phillips MR, Phillips BK, Phillips DE, Piel FB, Plass D, Poenaru D, Polinder S, Pope D, Popova S, Poulton RG, Pourmalek F, Prabhakaran D, Prasad NM, Pullan RL, Qato DM, Quistberg DA, Rafay A, Rahimi K, Rahman SU, Raju M, Rana SM, Razavi H, Reddy KS, Refaat A, Remuzzi G, Resnikoff S, Ribeiro AL, Richardson L, Richardus JH, Roberts DA, Rojas-Rueda D, Ronfani L, Roth GA, Rothenbacher D, Rothstein DH, Rowley JT, Roy N, Ruhago GM, Saeedi MY, Saha S, Sahraian MA, Sampson UK, Sanabria JR, Sandar L, Santos IS, Satpathy M, Sawhney M, Scarborough P, Schneider IJ, Schöttker B, Schumacher AE, Schwebel DC, Scott JG, Seedat S, Sepanlou SG, Serina PT, Servan-Mori EE, Shackelford KA, Shaheen A, Shahraz S, Shamah Levy T, Shangguan S, She J, Sheikhbahaei S, Shi P, Shibuya K, Shinohara Y, Shiri R, Shishani K, Shiue I, Shrime MG, Sigfusdottir ID, Silberberg DH, Simard EP, Sindi S, Singh A, Singh JA, Singh L, Skirbekk V, Slepak EL, Sliwa K, Soneji S, Søreide K, Soshnikov S, Sposato LA, Sreeramareddy CT, Stanaway JD, Stathopoulou V, Stein DJ, Stein MB, Steiner C, Steiner TJ, Stevens A, Stewart A, Stovner LJ, Stroumpoulis K, Sunguya BF, Swaminathan S, Swaroop M, Sykes BL, Tabb KM, Takahashi K, Tandon N, Tanne D, Tanner M, Tavakkoli M, Taylor HR, Te Ao BJ, Tediosi F, Temesgen AM, Templin T, Ten Have M, Tenkorang EY, Terkawi AS, Thomson B, Thorne-Lyman AL, Thrift AG, Thurston GD, Tillmann T, Tonelli M, Topouzis F, Toyoshima H, Traebert J, Tran BX, Trillini M, Truelsen T, Tsilimbaris M, Tuzcu EM, Uchendu US, Ukwaja KN, Undurraga EA, Uzun SB, Van Brakel WH, Van De Vijver S, van Gool CH, Van Os J, Vasankari TJ, Venketasubramanian N, Violante FS, Vlassov VV, Vollset SE, Wagner GR, Wagner J, Waller SG, Wan X, Wang H, Wang J, Wang L, Warouw TS, Weichenthal S, Weiderpass E, Weintraub RG, Wenzhi W, Werdecker A, Westerman R, Whiteford HA, Wilkinson JD, Williams TN, Wolfe CD, Wolock TM, Woolf AD, Wulf S, Wurtz B, Xu G, Yan LL, Yano Y, Ye P, Yentür GK, Yip P, Yonemoto N, Yoon SJ, Younis MZ, Yu C, Zaki ME, Zhao Y, Zheng Y, Zonies D, Zou X, Salomon JA, Lopez AD, Vos T. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990-2013: quantifying the epidemiological transition. Lancet. 2015;386:2145–2191. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61340-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen AM, Kim WR. Epidemiology and Healthcare Burden of Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure. Semin Liver Dis. 2016;36:123–126. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1583201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pimpin L, Cortez-Pinto H, Negro F, Corbould E, Lazarus JV, Webber L, Sheron N EASL HEPAHEALTH Steering Committee. Burden of liver disease in Europe: Epidemiology and analysis of risk factors to identify prevention policies. J Hepatol. 2018;69:718–735. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arroyo V, Moreau R, Kamath PS, Jalan R, Ginès P, Nevens F, Fernández J, To U, García-Tsao G, Schnabl B. Acute-on-chronic liver failure in cirrhosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16041. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ginés P, Quintero E, Arroyo V, Terés J, Bruguera M, Rimola A, Caballería J, Rodés J, Rozman C. Compensated cirrhosis: natural history and prognostic factors. Hepatology. 1987;7:122–128. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840070124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines on the management of ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2010;53:397–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2018;69:406–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blei AT, Córdoba J Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Hepatic Encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1968–1976. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J. Management of varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:823–832. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0901512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arvaniti V, D'Amico G, Fede G, Manousou P, Tsochatzis E, Pleguezuelo M, Burroughs AK. Infections in patients with cirrhosis increase mortality four-fold and should be used in determining prognosis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1246–1256. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trebicka J, Reiberger T, Laleman W. Gut-Liver Axis Links Portal Hypertension to Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure. Visc Med. 2018;34:270–275. doi: 10.1159/000490262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schnabl B, Brenner DA. Interactions between the intestinal microbiome and liver diseases. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1513–1524. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartmann P, Seebauer CT, Schnabl B. Alcoholic liver disease: the gut microbiome and liver cross talk. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:763–775. doi: 10.1111/acer.12704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tripathi A, Debelius J, Brenner DA, Karin M, Loomba R, Schnabl B, Knight R. The gut-liver axis and the intersection with the microbiome. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:397–411. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0011-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiest R, Garcia-Tsao G. Bacterial translocation (BT) in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2005;41:422–433. doi: 10.1002/hep.20632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernardi M, Moreau R, Angeli P, Schnabl B, Arroyo V. Mechanisms of decompensation and organ failure in cirrhosis: From peripheral arterial vasodilation to systemic inflammation hypothesis. J Hepatol. 2015;63:1272–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schuppan D, Afdhal NH. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2008;371:838–851. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60383-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dooley JS, Lok SA, Garcia-Tsao G, Pinzani M. 2011. Sherlock's diseases of the liver and biliary system. 12th ed. Wiley-Blackwell Pub; pp. 103–120. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsochatzis EA, Bosch J, Burroughs AK. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2014;383:1749–1761. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reiberger T, Mandorfer M. Beta adrenergic blockade and decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2017;66:849–859. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bosch J, Groszmann RJ, Shah VH. Evolution in the understanding of the pathophysiological basis of portal hypertension: How changes in paradigm are leading to successful new treatments. J Hepatol. 2015;62:S121–S130. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bosch J, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, García-Pagan JC. The clinical use of HVPG measurements in chronic liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:573–582. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ripoll C, Groszmann RJ, Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J, Grace N, Burroughs A, Planas R, Escorsell A, Garcia-Pagan JC, Makuch R, Patch D, Matloff DS Portal Hypertension Collaborative Group. Hepatic venous pressure gradient predicts development of hepatocellular carcinoma independently of severity of cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2009;50:923–928. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Villanueva C, Albillos A, Genescà J, Abraldes JG, Calleja JL, Aracil C, Bañares R, Morillas R, Poca M, Peñas B, Augustin S, Garcia-Pagan JC, Pavel O, Bosch J. Development of hyperdynamic circulation and response to β-blockers in compensated cirrhosis with portal hypertension. Hepatology. 2016;63:197–206. doi: 10.1002/hep.28264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turco L, Garcia-Tsao G, Magnani I, Bianchini M, Costetti M, Caporali C, Colopi S, Simonini E, De Maria N, Banchelli F, Rossi R, Villa E, Schepis F. Cardiopulmonary hemodynamics and C-reactive protein as prognostic indicators in compensated and decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2018;68:949–958. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pijls KE, Jonkers DM, Elamin EE, Masclee AA, Koek GH. Intestinal epithelial barrier function in liver cirrhosis: an extensive review of the literature. Liver Int. 2013;33:1457–1469. doi: 10.1111/liv.12271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Groszmann RJ. Hyperdynamic circulation of liver disease 40 years later: pathophysiology and clinical consequences. Hepatology. 1994;20:1359–1363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bolognesi M, Di Pascoli M, Verardo A, Gatta A. Splanchnic vasodilation and hyperdynamic circulatory syndrome in cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:2555–2563. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i10.2555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sriskandan S, Altmann DM. The immunology of sepsis. J Pathol. 2008;214:211–223. doi: 10.1002/path.2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE. The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:138–150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu D, Cao S, Zhou Y, Xiong Y. Recent advances in endotoxin tolerance. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:56–70. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Racanelli V, Rehermann B. The liver as an immunological organ. Hepatology. 2006;43:S54–S62. doi: 10.1002/hep.21060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clària J, Stauber RE, Coenraad MJ, Moreau R, Jalan R, Pavesi M, Amorós À, Titos E, Alcaraz-Quiles J, Oettl K, Morales-Ruiz M, Angeli P, Domenicali M, Alessandria C, Gerbes A, Wendon J, Nevens F, Trebicka J, Laleman W, Saliba F, Welzel TM, Albillos A, Gustot T, Benten D, Durand F, Ginès P, Bernardi M, Arroyo V. CANONIC Study Investigators of the EASL-CLIF Consortium and the European Foundation for the Study of Chronic Liver Failure (EF-CLIF), Systemic inflammation in decompensated cirrhosis: Characterization and role in acute-on-chronic liver failure. Hepatology. 2016;64:1249–1264. doi: 10.1002/hep.28740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waidmann O, Brunner F, Herrmann E, Zeuzem S, Piiper A, Kronenberger B. Macrophage activation is a prognostic parameter for variceal bleeding and overall survival in patients with liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2013;58:956–961. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tilg H, Diehl AM. Cytokines in alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1467–1476. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011163432007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robinson MW, Harmon C, O'Farrelly C. Liver immunology and its role in inflammation and homeostasis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;13:267–276. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2016.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seki E, Schnabl B. Role of innate immunity and the microbiota in liver fibrosis: crosstalk between the liver and gut. J Physiol. 2012;590:447–458. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.219691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uesugi T, Froh M, Arteel GE, Bradford BU, Thurman RG. Toll-like receptor 4 is involved in the mechanism of early alcohol-induced liver injury in mice. Hepatology. 2001;34:101–108. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Csak T, Ganz M, Pespisa J, Kodys K, Dolganiuc A, Szabo G. Fatty acid and endotoxin activate inflammasomes in mouse hepatocytes that release danger signals to stimulate immune cells. Hepatology. 2011;54:133–144. doi: 10.1002/hep.24341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tacke F. Targeting hepatic macrophages to treat liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2017;66:1300–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heymann F, Tacke F. Immunology in the liver--from homeostasis to disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:88–110. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Szabo G. Gut-liver axis in alcoholic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:30–36. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bala S, Marcos M, Gattu A, Catalano D, Szabo G. Acute binge drinking increases serum endotoxin and bacterial DNA levels in healthy individuals. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bode C, Kugler V, Bode JC. Endotoxemia in patients with alcoholic and non-alcoholic cirrhosis and in subjects with no evidence of chronic liver disease following acute alcohol excess. J Hepatol. 1987;4:8–14. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(87)80003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parlesak A, Schäfer C, Schütz T, Bode JC, Bode C. Increased intestinal permeability to macromolecules and endotoxemia in patients with chronic alcohol abuse in different stages of alcohol-induced liver disease. J Hepatol. 2000;32:742–747. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80242-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roh YS, Zhang B, Loomba R, Seki E. TLR2 and TLR9 contribute to alcohol-mediated liver injury through induction of CXCL1 and neutrophil infiltration. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015;309:G30–G41. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00031.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lippai D, Bala S, Catalano D, Kodys K, Szabo G. Micro-RNA-155 deficiency prevents alcohol-induced serum endotoxin increase and small bowel inflammation in mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:2217–2224. doi: 10.1111/acer.12483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoseph BP, Breed E, Overgaard CE, Ward CJ, Liang Z, Wagener ME, Lexcen DR, Lusczek ER, Beilman GJ, Burd EM, Farris AB, Guidot DM, Koval M, Ford ML, Coopersmith CM. Chronic alcohol ingestion increases mortality and organ injury in a murine model of septic peritonitis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Henao-Mejia J, Elinav E, Jin C, Hao L, Mehal WZ, Strowig T, Thaiss CA, Kau AL, Eisenbarth SC, Jurczak MJ, Camporez JP, Shulman GI, Gordon JI, Hoffman HM, Flavell RA. Inflammasome-mediated dysbiosis regulates progression of NAFLD and obesity. Nature. 2012;482:179–185. doi: 10.1038/nature10809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Loomba R, Seguritan V, Li W, Long T, Klitgord N, Bhatt A, Dulai PS, Caussy C, Bettencourt R, Highlander SK, Jones MB, Sirlin CB, Schnabl B, Brinkac L, Schork N, Chen CH, Brenner DA, Biggs W, Yooseph S, Venter JC, Nelson KE. Gut Microbiome-Based Metagenomic Signature for Non-invasive Detection of Advanced Fibrosis in Human Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Cell Metab. 2017;25:1054–1062.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bajaj JS, Heuman DM, Hylemon PB, Sanyal AJ, White MB, Monteith P, Noble NA, Unser AB, Daita K, Fisher AR, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet PM. Altered profile of human gut microbiome is associated with cirrhosis and its complications. J Hepatol. 2014;60:940–947. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yu LX, Schwabe RF. The gut microbiome and liver cancer: mechanisms and clinical translation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:527–539. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dapito DH, Mencin A, Gwak GY, Pradere JP, Jang MK, Mederacke I, Caviglia JM, Khiabanian H, Adeyemi A, Bataller R, Lefkowitch JH, Bower M, Friedman R, Sartor RB, Rabadan R, Schwabe RF. Promotion of hepatocellular carcinoma by the intestinal microbiota and TLR4. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:504–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seki E, De Minicis S, Osterreicher CH, Kluwe J, Osawa Y, Brenner DA, Schwabe RF. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/nm1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu LX, Yan HX, Liu Q, Yang W, Wu HP, Dong W, Tang L, Lin Y, He YQ, Zou SS, Wang C, Zhang HL, Cao GW, Wu MC, Wang HY. Endotoxin accumulation prevents carcinogen-induced apoptosis and promotes liver tumorigenesis in rodents. Hepatology. 2010;52:1322–1333. doi: 10.1002/hep.23845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weber SN, Bohner A, Dapito DH, Schwabe RF, Lammert F. TLR4 Deficiency Protects against Hepatic Fibrosis and Diethylnitrosamine-Induced Pre-Carcinogenic Liver Injury in Fibrotic Liver. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0158819. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Orci LA, Lacotte S, Delaune V, Slits F, Oldani G, Lazarevic V, Rossetti C, Rubbia-Brandt L, Morel P, Toso C. Effects of the gut-liver axis on ischaemia-mediated hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence in the mouse liver. J Hepatol. 2018;68:978–985. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marchiando AM, Graham WV, Turner JR. Epithelial barriers in homeostasis and disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010;5:119–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Van Itallie CM, Anderson JM. Architecture of tight junctions and principles of molecular composition. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;36:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van Itallie CM, Fanning AS, Anderson JM. Reversal of charge selectivity in cation or anion-selective epithelial lines by expression of different claudins. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;285:F1078–F1084. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00116.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yu AS, Cheng MH, Angelow S, Günzel D, Kanzawa SA, Schneeberger EE, Fromm M, Coalson RD. Molecular basis for cation selectivity in claudin-2-based paracellular pores: identification of an electrostatic interaction site. J Gen Physiol. 2009;133:111–127. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Van Itallie CM, Holmes J, Bridges A, Gookin JL, Coccaro MR, Proctor W, Colegio OR, Anderson JM. The density of small tight junction pores varies among cell types and is increased by expression of claudin-2. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:298–305. doi: 10.1242/jcs.021485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shen L, Weber CR, Turner JR. The tight junction protein complex undergoes rapid and continuous molecular remodeling at steady state. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:683–695. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200711165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Furuse M, Itoh M, Hirase T, Nagafuchi A, Yonemura S, Tsukita S, Tsukita S. Direct association of occludin with ZO-1 and its possible involvement in the localization of occludin at tight junctions. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1617–1626. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rajasekaran AK, Hojo M, Huima T, Rodriguez-Boulan E. Catenins and zonula occludens-1 form a complex during early stages in the assembly of tight junctions. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:451–463. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.3.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Imamura Y, Itoh M, Maeno Y, Tsukita S, Nagafuchi A. Functional domains of alpha-catenin required for the strong state of cadherin-based cell adhesion. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:1311–1322. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.6.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arab JP, Martin-Mateos RM, Shah VH. Gut-liver axis, cirrhosis and portal hypertension: the chicken and the egg. Hepatol Int. 2018;12:24–33. doi: 10.1007/s12072-017-9798-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim YS, Ho SB. Intestinal goblet cells and mucins in health and disease: recent insights and progress. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2010;12:319–330. doi: 10.1007/s11894-010-0131-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gassler N. Paneth cells in intestinal physiology and pathophysiology. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2017;8:150–160. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v8.i4.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Spadoni I, Pietrelli A, Pesole G, Rescigno M. Gene expression profile of endothelial cells during perturbation of the gut vascular barrier. Gut Microbes. 2016;7:540–548. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2016.1239681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Spadoni I, Zagato E, Bertocchi A, Paolinelli R, Hot E, Di Sabatino A, Caprioli F, Bottiglieri L, Oldani A, Viale G, Penna G, Dejana E, Rescigno M. A gut-vascular barrier controls the systemic dissemination of bacteria. Science. 2015;350:830–834. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.von Olshausen G, Quasdorff M, Bester R, Arzberger S, Ko C, van de Klundert M, Zhang K, Odenthal M, Ringelhan M, Niessen CM, Protzer U. Hepatitis B virus promotes β-catenin-signalling and disassembly of adherens junctions in a Src kinase dependent fashion. Oncotarget. 2018;9:33947–33960. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang Y, Tong J, Chang B, Wang B, Zhang D, Wang B. Effects of alcohol on intestinal epithelial barrier permeability and expression of tight junction-associated proteins. Mol Med Rep. 2014;9:2352–2356. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tang Y, Banan A, Forsyth CB, Fields JZ, Lau CK, Zhang LJ, Keshavarzian A. Effect of alcohol on miR-212 expression in intestinal epithelial cells and its potential role in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:355–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rao R. Endotoxemia and gut barrier dysfunction in alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;50:638–644. doi: 10.1002/hep.23009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]