Abstract

The role of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection in patients following endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer (EGC) remains unclear. This article presents a review of literature published in the past 15 years. H. pylori‐mediated persistent methylation levels are associated with the development of metachronous gastric cancer. The methylation of certain specific genes can be used to identify patients with a high risk of metachronous gastric cancer even after H. pylori eradication. H. pylori eradication after endoscopic resection should be performed as early as possible for eradication success and prevention of metachronous precancerous lesions. Although whether the eradication of H. pylori could prevent the development of metachronous cancer after endoscopic resection is controversial, several meta‐analyses concluded that H. pylori eradication could reduce the incidence of metachronous gastric cancer significantly. In addition, H. pylori eradication in gastric cancer survivors after endoscopic resection could reduce healthcare cost and save lives in a cost‐effective way. Taken together, H. pylori eradication after endoscopic resection of EGC is recommended as prevention for metachronous precancerous lesions and metachronous gastric cancer.

1. Introduction

In recent years, endoscopic resection including endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has been widely used in the treatment of early gastric cancer (EGC) [1]. The risk of the development of metachronous gastric cancer in patients who underwent endoscopic resection of EGC is higher than that in gastrectomized patients. Endoscopic resection is minimally invasive and preserves the whole stomach, which could increase the risk of metachronous cancers on unresected parts of the stomach compared to surgical resection [2, 3]. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is the major cause of gastric carcinogenesis, and its infection leads to chronic gastritis, atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and subsequently to gastric adenocarcinoma [4, 5]. The role of H. pylori infection in patients following endoscopic resection of EGC remains unclear due to different results from various studies. It is still controversial whether the eradication of H. pylori can reduce the likelihood of metachronous gastric cancer. In the present study, we will review the literature on the relationship between H. pylori infection and metachronous gastric lesion after endoscopic resection. The purpose of the present study is to explore the role of H. pylori infection and H. pylori eradication in the patients after endoscopic resection of EGC.

2. Prevalence of H. pylori Infection after Endoscopic Resection of Early Gastric Cancer

Endoscopic therapy is a minimally invasive treatment that allows the patient to preserve the entire stomach. The anatomy of the stomach has no significant change after endoscopic resection for EGC, but few studies have examined whether the microbiological profile in the stomach has changed. Prevalence of H. pylori infection after endoscopic resection for EGC has seldom been reported. Hwang et al. reported that H. pylori infection rate after endoscopic resection of EGC was significantly higher in the patients with residual tumors group than in the patients without residual tumors group [6]. Moreover, H. pylori were independent factors of the presence of residual tumor in additional gastrectomy after incomplete endoscopic resection for EGC [6]. Large‐scale studies are needed to determine whether there is a difference in H. pylori infection rate between general population and the patients following endoscopic surgery of EGC.

3. Effect of H. pylori on Ulcers Developing after Endoscopic Resection of Early Gastric Cancer

Several studies have examined the effect of H. pylori eradication on ulcers developing after endoscopic resection of EGC. Song et al. suggested that early H. pylori eradication therapy can promote H. pylori-positive ESD‐induced artificial ulcer healing [7]. Cheon et al. found that H. pylori eradication was better than PPI treatment with respect to the healing of artificial gastric ulcer after EMR for EGC [8]. It was reported that H. pylori infection led to decreased mucosal blood flow at the margin of EMR‐induced ulcers, which indirectly supports the above report [9]. However, in one study concerning the effect of H. pylori infection status on post‐EMR gastric ulcers by Kakushima et al. [10], the healing rate of ulcers at 8 weeks after EMR was not affected by H. pylori infection status. Likewise, several reports have shown that the infection status of H. pylori does not affect ulcer healing after ESD [10–14]. The reasons for these are as follows: Eradication therapy promotes the healing process of peptic ulcers by improving microcirculation. However, muscular contraction might be a major factor in the healing process of artificial ulcers, while improvement of microcirculation is only a secondary factor. In addition, the pathogenesis of artificial ulcers is completely mechanical rather than H. pylori‐induced apoptosis or gastric juice‐induced degradation. Further follow‐up prospective studies will help to clarify the effect of H. pylori on ulcers developing after endoscopic resection of EGC.

4. Molecular Pathogenesis of H. pylori‐Related Metachronous Gastric Cancer

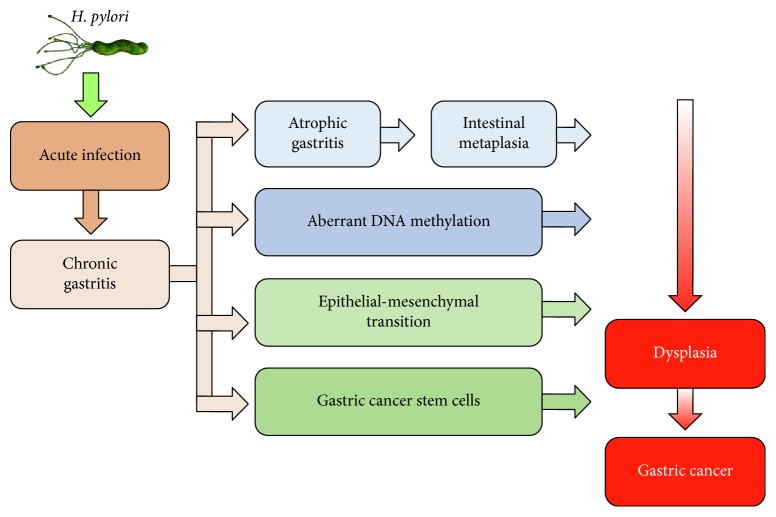

The current studies found that the mechanisms by which H. pylori infection might eventually lead to gastric cancer included H. pylori‐induced atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia, aberrant DNA methylation, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, and gastric cancer stem cells (Figure 1) [15]. Chronic active H. pylori infection leads to the recruitment of immune cells, increasing secretion of interleukin‐1β, tumor necrosis factor‐α, and reactive oxygen species, which together cause the activation of DNA methyltransferase 1, mediating abnormal DNA methylation in the gastric mucosa [16]. The methylation level in gastric mucosa is partially reversible by H. pylori eradication in a gene‐specific manner [17–19], but the methylation of some molecules in stem cells can last for a long time [20]. Thus, it is likely that the methylation level after H. pylori eradication could reflect the epigenomic damage of stem cells [20, 21]. It was reported that the methylation of MOS and miR‐124a‐3 could predict the risk of metachronous gastric cancer [20, 22]. The methylation level of MOS in patients with metachronous gastric cancer was significantly higher than that in patients without metachronous gastric cancer [22]. Likewise, high miR‐124a‐3 methylation level was correlated with an increased risk of developing metachronous gastric cancers [20]. Therefore, H. pylori‐mediated persistent methylation levels are associated with the development of metachronous gastric cancer. The methylation of certain specific genes can be used to identify patients with a high risk of metachronous gastric cancer even after H. pylori eradication.

Figure 1.

A model representing the role of H. pylori in the development of gastric cancer.

5. Effect of H. pylori on Metachronous Precancerous Lesions after Endoscopic Resection of Early Gastric Cancer

Many studies reported the results concerning the effect of H. pylori on gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia following endoscopic resection of EGC. Choi et al. [23] and Han et al. [24] reported that the grade of atrophy on corpus was significantly lower in the H. pylori‐eradicated group than in the persistent group during a follow‐up period longer than 5 years after endoscopic treatment of EGC. Zhang et al. found that H. pylori infection was an independent risk factor for recurrence of gastric mucosal dysplasia after endoscopic resection [25]. Similarly, the multivariate analysis by Chon et al. showed that eradication of H. pylori was related to reduce incidence of subsequent gastric dysplasia [26]. Of particular significance is the observation that failure of H. pylori eradication occurred more frequently in metachronous patients with gastric dysplasia than in those with carcinoma [27]. In other words, eradication failure was closely related to dysplasia, but not carcinoma, in the metachronous group. Therefore, H. pylori infection could play a role in the development of metachronous precancerous lesions after endoscopic resection of EGC. There may be a ‘point of no return,' beyond which molecular changes are irreversible and H. pylori eradication could no longer prevent metachronous lesions. It is difficult to correctly define the point of no return because the molecular process cannot be determined precisely. On the basis of the above studies, H. pylori eradication after endoscopic resection of EGC should be performed as early as possible for the prevention of metachronous precancerous lesions.

6. Effect of H. pylori Eradication on the Development of Metachronous Gastric Cancer

Although H. pylori is a well‐known risk factor and plays an important role in the development of gastric cancer, the effect of H. pylori infection on the development of metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of EGC still remains unclear [28]. The mucosa adjacent to H. pylori‐infected gastric cancer is usually accompanied by atrophy and intestinal metaplasia, which is susceptible to develop metachronous gastric cancer. Endoscopic resection preserves the gastric mucosa to the greatest extent, so the incidence of metachronous gastric cancer in the abnormal background mucosa is significantly increased [2]. Previous studies illustrated that persistent H. pylori infection was associated with an increased risk of subsequent gastric dysplasia or cancer after endoscopic resection of EGC, and H. pylori infection is an independent risk factors for metachronous gastric cancer after ESD of EGC [29–31]. However, Lim et al. showed an inverse relationship between H. pylori infection and metachronous gastric cancer [32]. One possible reason is that H. pylori‐negative patients may have previously been infected with H. pylori and previous long‐term infection might have a greater effect on the development of metachronous gastric cancer than newly developed current infection.

It is still on debate whether the eradication of H. pylori could prevent the development of metachronous cancer after endoscopic resection of EGC. Several long follow‐up prospective studies reported that eradication of H. pylori in the patients treated with endoscopic resection of gastric dysplasia or EGC could reduce the risk of metachronous cancer [23, 33, 34]. However, a 3‐year prospective study by Choi et al. reported that the cumulative incidence of metachronous gastric cancer was not different between patients with or without H. pylori eradication [35]. Other retrospective studies showed similarly controversial conclusions [26, 27, 31, 36–40]. The reasons for this discrepancy are as follows: First, the study designs were different among the studies. Some were prospective randomized trials, and others were retrospective cohort studies. Second, the timing of the H. pylori eradication was not consistent. Some persons received eradication treatment immediately after endoscopic resection, and others received treatment several months after endoscopic resection. Third, the follow‐up time was not consistent among the studies and most studies had a follow‐up period of less than 5 years. In addition, the methods for calculations of the observation period were different among the studies. Some started from eradication of H. pylori, and others started from the initial ESD.

Nevertheless, several meta‐analyses concluded that H. pylori eradication could reduce the incidence of metachronous gastric cancer significantly, therefore preventing against metachronous gastric cancer in patients who have undergone endoscopic resection [41–44]. Although it is possible to develop metachronous gastric cancer after successful eradication of H. pylori, H. pylori eradication after endoscopic resection of EGC is still recommended in the Maastricht consensus report and the Guidelines of the Japanese Gastroenterological Society [45, 46]. Further prospective studies with long‐term follow‐up could help clarify the effect of H. pylori eradication in preventing metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of EGC.

Furthermore, Park et al. clarified that H. pylori infection or eradication did not affect the time interval between the initial ESD and the development of metachronous gastric cancer [47], which implied that H. pylori eradication might not halt the progression of precancerous lesions, especially when the neoplastic change has reached a certain degree. A possible reason is that metachronous gastric lesions might have already been in the stomach at the time of ESD for EGC as tiny or invisible lesions, and therefore, the time interval to occurrence of metachronous gastric cancer might not be affected by H. pylori eradication in patients with undetected early cancer or slowly growing latent cancer [48].

7. Optimal Timing for H. pylori Eradication for Patients after Endoscopic Resection of Early Gastric Cancer

Few studies have explored the optimal timing to eradicate H. pylori after endoscopic resection of EGC. Huh et al. assessed whether the eradication of H. pylori at different time points after endoscopic resection affected the success rates of eradication therapy [49]. They concluded that the early treatment group (≤2 weeks after endoscopic resection) achieved a significantly higher eradication rate than the intermediate group (2–8 weeks) or the late group (≥8 weeks). Multivariate analysis showed that early initiation of H. pylori eradication therapy was an independent significant predictor of eradication success. On the other hand, it was reported that H. pylori eradication in the patients who underwent ESD for EGC should be performed before the progression of gastric mucosal atrophy [36]. The presence of moderate‐to‐severe mucosal atrophy or intestinal metaplasia may be a ‘point of no return' and does not appear to regress following H. pylori eradication [36, 50]. These results suggest that eradication of H. pylori as early as possible after endoscopic surgery offers the greatest chance of eradication success.

8. Cost‐Effectiveness of H. pylori Eradication in Patients after Endoscopic Resection of Early Gastric Cancer

Patients after endoscopic resection of EGC are more susceptible to metachronous gastric cancer and might benefit more from H. pylori eradication. Shin et al. reported that the health care cost for patients after endoscopic resection of EGC was significantly lower in H. pylori eradication group than in no eradication group (US$29,780 vs. US$30,594), while mean life expectancy from eradication was significantly longer in H. pylori eradication group (13.60 years vs. 13.55 years) [51]. Therefore, eradication of H. pylori in gastric cancer survivors after endoscopic resection could reduce healthcare costs while saving lives, and these findings have favorable implication in decision making about the most appropriate treatment option after endoscopic resection of EGC. Large‐scale studies are needed to clarify whether this strategy could be cost‐effective in selective population with high risk of developing metachronous gastric cancer.

9. Conclusion

In this review, we summarized the studies addressing H. pylori infection after endoscopic resection of EGC. Unfortunately, prevalence of H. pylori infection after endoscopic resection of EGC has seldom been reported. The effect of H. pylori eradication on ulcers developing after endoscopic resection is still on debate.

H. pylori‐mediated persistent methylation levels are associated with the development of metachronous gastric cancer. The methylation of certain specific genes can be used to identify patients with a high risk of metachronous gastric cancer even after H. pylori eradication. H. pylori eradication after endoscopic resection should be performed as early as possible for eradication success and prevention of metachronous precancerous lesions. Although whether the eradication of H. pylori could prevent the development of metachronous cancer after endoscopic resection is controversial, several meta‐analyses concluded that H. pylori eradication could reduce the incidence of metachronous gastric cancer significantly. In addition, H. pylori eradication in gastric cancer survivors after endoscopic resection could reduce health care cost and save lives in a cost‐effective way. Taken together, H. pylori eradication after endoscopic resection of EGC is recommended as prevention for metachronous precancerous lesions and metachronous gastric cancer. A large‐scale, long‐term research is needed to examine the role of H. pylori infection and H. pylori eradication in the patients following endoscopic resection of EGC.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81400606), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LY17H030004), and Science and Technology plan projects of Zhejiang Province (2015C33102).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

References

- 1.Nishizawa T., Yahagi N. Long‐term outcomes of using endoscopic submucosal dissection to treat early gastric cancer. Gut and Liver. 2018;12(2):119–124. doi: 10.5009/gnl17095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gotoda T. Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2007;10(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10120-006-0408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abe S., Oda I., Minagawa T., et al. Metachronous gastric cancer following curative endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Clinical Endoscopy. 2018;51(3):253–259. doi: 10.5946/ce.2017.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Correa P., Houghton J. Carcinogenesis of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(2):659–672. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alfarouk K. O., Bashir A. H. H., Aljarbou A. N., et al. The possible role of helicobacter pylori in gastric cancer and its management. Frontiers in Oncology. 2019;9:p. 75. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hwang J. J., Lee D. H., Yoon H., Shin C. M., Park Y. S., Kim N. Clinicopathological characteristics of patients who underwent additional gastrectomy after incomplete endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(7):p. e6172. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song W. C., Wang X. F., Lv W. W., Xu X. Y., Tian M. The effect of early Helicobacter pylori eradication on the healing of ESD‐induced artificial ulcers: a retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98(22):p. e15807. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheon J. H., Kim J. H., Lee S. K., Kim T. I., Kim W. H., Lee Y. C. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy may facilitate gastric ulcer healing after endoscopic mucosal resection: a prospective randomized study. Helicobacter. 2008;13(6):564–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2008.00647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adachi K., Suetsugu H., Moriyama N., et al. Influence of Helicobacter pylori infection and cetraxate on gastric mucosal blood flow during healing of endoscopic mucosal resection‐induced ulcers. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2001;16(11):1211–1216. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2001.02606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kakushima N., Fujishiro M., Yahagi N., Kodashima S., Nakamura M., Omata M. Helicobacter pylori status and the extent of gastric atrophy do not affect ulcer healing after endoscopic submucosal dissection. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2006;21(10):1586–1589. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshizawa Y., Sugimoto M., Sato Y., et al. Factors associated with healing of artificial ulcer after endoscopic submucosal dissection with reference to Helicobacter pylori infection, CYP2C19 genotype, and tumor location: multicenter randomized trial. Digestive Endoscopy. 2016;28(2):162–172. doi: 10.1111/den.12544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim S. G., Song H. J., Choi I. J., et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication on iatrogenic ulcer by endoscopic resection of gastric tumour: a prospective, randomized, placebo‐controlled multi‐centre trial. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2013;45(5):385–389. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J., Guo X., Ye C., et al. Efficacy and safety of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) plus rebamipide for endoscopic submucosal dissection‐induced ulcers: a meta‐analysis. Internal Medicine. 2014;53(12):1243–1248. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim J. H., Kim S. G., Choi J., Im J. P., Kim J. S., Jung H. C. Risk factors of delayed ulcer healing after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. Surgical Endoscopy. 2015;29(12):3666–3673. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4123-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim N. Chemoprevention of gastric cancer by Helicobacter pylori eradication and its underlying mechanism. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2019 doi: 10.1111/jgh.14646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiba T., Marusawa H., Ushijima T. Inflammation‐associated cancer development in digestive organs: mechanisms and roles for genetic and epigenetic modulation. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(3):550–563. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perri F., Cotugno R., Piepoli A., et al. Aberrant DNA methylation in non‐neoplastic gastric mucosa of H. pylori infected patients and effect of eradication. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2007;102(7):1361–1371. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakajima T., Enomoto S., Yamashita S., et al. Persistence of a component of DNA methylation in gastric mucosae after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;45(1):37–44. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shin C. M., Kim N., Lee H. S., et al. Changes in aberrant DNA methylation after Helicobacter pylori eradication: a long‐term follow‐up study. International Journal of Cancer. 2013;133(9):2034–2042. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asada K., Nakajima T., Shimazu T., et al. Demonstration of the usefulness of epigenetic cancer risk prediction by a multicentre prospective cohort study. Gut. 2015;64(3):388–396. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maeda M., Moro H., Ushijima T. Mechanisms for the induction of gastric cancer by Helicobacter pylori infection: aberrant DNA methylation pathway. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20(S1):8–15. doi: 10.1007/s10120-016-0650-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoon H., Kim N., Shin C. M., et al. Risk factors for metachronous gastric neoplasms in patients who underwent endoscopic resection of a gastric neoplasm. Gut and Liver. 2016;10(2):228–236. doi: 10.5009/gnl14472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi I. J., Kook M. C., Kim Y. I., et al. Helicobacter pylori therapy for the prevention of metachronous gastric cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;378(12):1085–1095. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1708423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han S. J., Kim S. G., Lim J. H., et al. Long‐Term Effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication on metachronous gastric cancer development. Gut and Liver. 2018;12(2):133–141. doi: 10.5009/gnl17073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang L., Wang H. Prognostic analysis of gastric mucosal dysplasia after endoscopic resection: a single‐center retrospective study. Journal of BUON. 2019;24(2):679–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chon I., Choi C., Shin C. M., Park Y. S., Kim N., Lee D. H. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on subsequent dysplasia development after endoscopic resection of gastric dysplasia. The Korean journal of gastroenterology. 2013;61(6):307–312. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.04.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jung D. H., Kim J. H., Lee Y. C., et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication reduces the metachronous recurrence of gastric neoplasms by attenuating the precancerous process. Journal of Gastric Cancer. 2015;15(4):246–255. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2015.15.4.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ami R., Hatta W., Iijima K., et al. Factors associated with metachronous gastric cancer development after endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2017;51(6):494–499. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chung C. S., Woo H. S., Chung J. W., et al. Risk factors for metachronous recurrence after endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. Journal of Korean Medical Science. 2017;32(3):421–426. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.3.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jung S., Park C. H., Kim E. H., et al. Preventing metachronous gastric lesions after endoscopic submucosal dissection through Helicobacter pylori eradication. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2015;30(1):75–81. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwon Y. H., Heo J., Lee H. S., Cho C. M., Jeon S. W. Failure of Helicobacter pylori eradication and age are independent risk factors for recurrent neoplasia after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer in 283 patients. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2014;39(6):609–618. doi: 10.1111/apt.12633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lim J. H., Kim S. G., Choi J., et al. Risk factors for synchronous or metachronous tumor development after endoscopic resection of gastric neoplasms. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18(4):817–823. doi: 10.1007/s10120-014-0438-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukase K., Kato M., Kikuchi S., et al. Effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer: an open‐label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9636):392–397. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(08)61159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi J. M., Kim S. G., Choi J., et al. Effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication for metachronous gastric cancer prevention: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2018;88(3):475–485.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2018.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi J., Kim S. G., Yoon H., et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori after endoscopic resection of gastric tumors does not reduce incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2014;12(5):793–800.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maehata Y., Nakamura S., Fujisawa K., et al. Long‐term effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the development of metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2012;75(1):39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim Y. I., Choi I. J., Kook M. C., et al. The association between Helicobacter pylori status and incidence of metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Helicobacter. 2014;19(3):194–201. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(13)61202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shiotani A., Uedo N., Iishi H., et al. Predictive factors for metachronous gastric cancer in high‐risk patients after successful Helicobacter pylori eradication. Digestion. 2008;78(2–3):113–119. doi: 10.1159/000173719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seo J. Y., Lee D. H., Cho Y., et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori reduces metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60(124):776–780. doi: 10.5754/hge12929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bae S. E., Jung H. Y., Kang J., et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori Eradication on Metachronous Recurrence After Endoscopic Resection of Gastric Neoplasm. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2014;109(1):60–67. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoon S. B., Park J. M., Lim C. H., Cho Y. K., Choi M.‐G. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of gastric tumors: a meta‐analysis. Helicobacter. 2014;19(4):243–248. doi: 10.1111/hel.12146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jung D. H., Kim J. H., Chung H. S., et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication on the prevention of metachronous lesions after endoscopic resection of gastric neoplasm: a meta‐analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):p. e0124725. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiao S., Li S., Zhou L., Jiang W., Liu J. Helicobacter pylori status and risks of metachronous recurrence after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Gastroenterology. 2019;54(3):226–237. doi: 10.1007/s00535-018-1513-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bang C. S., Baik G. H., Shin I. S., et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication for prevention of metachronous recurrence after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Journal of Korean Medical Science. 2015;30(6):749–756. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.6.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.European Helicobacter pylori Study Group. Current European concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. The Maastricht consensus report. Gut. 1997;41(1):8–13. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ono H., Yao K., Fujishiro M., et al. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Digestive Endoscopy. 2016;28(1):3–15. doi: 10.1111/den.12518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park J. Y., Kim S. G., Kim J., et al. Risk factors for early metachronous tumor development after endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):p. e0185501. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori, IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Lyon, 7–14 June 1994. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. 1994;61:1–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huh C. W., Youn Y. H., Jung D. H., Park J. J., Kim J.‐H., Park H. Early attempts to eradicate helicobacter pylori after endoscopic resection of gastric neoplasm significantly improve eradication success rates. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):p. e0162258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wong B. C.‐Y., Lam S. K., Wong W. M., et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high‐risk region of China. JAMA. 2004;291(2):187–194. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shin D. W., Yun Y. H., Choi I. J., Koh E., Park S. M. Cost‐effectiveness of eradication of Helicobacter pylori in gastric cancer survivors after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Helicobacter. 2009;14(6):536–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]