Abstract

Aims

Heart failure (HF) burden is displaying significant inter‐regional differences within Europe and within countries. Due to limited data focusing on regional differences, our aim was to evaluate HF hospitalizations, readmissions, and mortality burden in Slovenian statistical regions.

Methods and results

The Slovenian National Hospitalization Discharge Registry was searched for HF hospitalizations in patients 20 years or over in the period 2004–12. Annual sex and age‐standardized HF hospitalizations, mortality, and HF readmissions rates were calculated for Slovenia and for each Slovenian statistical region. Trends were evaluated using ANOVA. Multiple mixed effect logistic regression models, which included statistical region, admission year, sex, age, intensive care unit treatment, and co‐morbidities as a fixed effect and hospital identifier as a random effect, were calculated for mortality and readmissions. Overall, 156 859 HF hospitalizations (55 522 where HF was coded as a main diagnosis and 43 606 as first HF hospitalizations) were recorded. Annual standardized rates varied considerably between statistical regions for main (220–511) and first HF hospitalization (392–721), 30 day (12.6–27.1) and 1 year mortality (66–117), and 30 day (31–80.8) and 1 year readmission (99–24) (per 100 000 patient years in 2012). Yearly decline in HF hospitalization rates was seen for national main (3.6; 0.001) and first (8.4; 0.083) HF hospitalizations, while individual regional main and first HF hospitalization trends mostly did not reach statistical significance. No relevant differences in mortality and readmission endpoints for statistical regions were seen when adjusted for patient demographics and specific co‐morbidities.

Conclusions

Significant regional differences in standardized HF hospitalization, mortality, and readmissions between the regions were seen. There were no differences in mortality and readmissions between statistical regions for individual similar patients.

Keywords: Heart failure, Hospitalizations, Regional differences, Mortality, Readmissions

Introduction

Despite the reduction in mortality due to cardiovascular (CV) disease in recent decade, CV disease remains the leading cause of death in Slovenia and European countries.1, 2 The prevalence of heart failure (HF), the end stage of several CV diseases, is decreasing due to better prevention and management of CV diseases and is estimated at around 2%.3 Patients with HF have significantly reduced health‐related quality of life and worse outcomes in terms of morbidity and mortality.4, 5 This makes HF an important public health problem, which is mainly reflected by high socio‐economic burden and high dependency on health care services.4, 6, 7

Similarly to CV disease, HF burden is displaying significant inter‐regional differences within Europe, with eastern European countries reporting higher mortality rates.2, 8 Such an East–West health gap, a variation in CV prevalence, mortality, risk factors, and other determinants of health are not apparent only across a continent (e.g. Europe) but is also seen on a national level.1, 9 In the USA, similar observations have been reported: lower socio‐economic status and lower number of primary care physicians per inhabitant were related to higher mortality rates at level of counties and states.10, 11, 12

In Europe and Slovenia, limited epidemiologic data that focus on inter‐regional differences at a national level are available for HF. Our aim was to evaluate HF hospitalizations, readmissions, and mortality burden in Slovenian statistical regions.

Methods

Study design and sample

This was a nationwide, retrospective, epidemiologic, observational study in patients aged 20 years or over who were hospitalized with HF in Slovenia between 2004 and 2012. Hospitalization data were obtained from the National Hospital Discharge Registry and coupled with National Death Registry both of the National Institute of Public Health using unique person identification number. We excluded HF hospitalizations where patients had permanent residence outside Slovenia, were younger than 20, had mismatch between date of death and admission, and were missing region of permanent residence.

Slovenia is a central European country with about 2 million inhabitants who are divided into 12 different statistical regions (Table 1). The number of residents in each statistical region in 2011 varied from 44 222 (Zasavska) to 533 213 (Osrednjeslovenska) with a mean number of 166 369 (Table 1). Slovenia has a universal Bismarckian type of social insurance health care system. Most of the inpatient care is delivered by state‐owned hospitals that include regional general hospitals, specialized clinics (e.g. psychiatric, pulmonary, obstetric, or orthopaedics), rehabilitation clinics, and two tertiary centres. Reporting to the National Hospital Discharge Registry is mandatory for all Slovenian hospitals.

Table 1.

Characteristics by statistical regions

| Osrednje‐slovenska | Pomurska | Podravska | Koroška | Savinjska | Zasavska | Posavska | Jugovzhodna Slovenija | Gorenjska | Primorsko‐notranjska | Goriška | Obalno‐kraška | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population, N (%) | 427 103 (25.8) | 97 599 (5.9) | 265 031 (16) | 58 485 (3.5) | 208 805 (12.6) | 36 423 (2.2) | 56 925 (3.4) | 113 105 (6.8) | 161 878 (9.8) | 42 397 (2.6) | 96 915 (5.8) | 92 144 (5.6) |

| HF hospitalizations, N (%) | 8098 (18.6) | 3782 (8.7) | 7745 (17.8) | 1643 (3.8) | 5183 (11.9) | 1531 (3.5) | 2424 (5.6) | 2854 (6.5) | 3865 (8.9) | 1012 (2.3) | 3249 (7.5) | 2220 (5.1) |

| Male sex (%) | 45.8 | 42.6 | 45.2 | 46.1 | 46.6 | 44.0 | 46.0 | 47.4 | 45.2 | 46.2 | 45.9 | 49.3 |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 79 (71–85) | 78 (69–84) | 78 (70–84) | 77 (69–83) | 77 (69–83) | 78 (69–84) | 78 (70–84) | 77 (70–83) | 79 (71–84) | 79 (72–85) | 80 (72–85) | 79 (71–85) |

| Hospitalization length (days), median (IQR) | 9 (4–16) | 9 (5–15) | 9 (5–15) | 7 (3–12) | 7 (3–12) | 8 (4–15) | 8 (4–14) | 10 (4–17) | 7 (4–13) | 8 (4–14) | 8 (4–13) | 7 (4–12) |

| Arterial hypertension (%) | 64.3 | 51.9 | 49.2 | 73.1 | 53.7 | 66.4 | 67.0 | 69.8 | 61.1 | 63.0 | 50.8 | 59.8 |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 37.6 | 33.9 | 31.8 | 38.8 | 35.7 | 35.7 | 29.8 | 43.0 | 34.0 | 38.1 | 30.9 | 39.0 |

| Myocardial infarction (%) | 8.8 | 6.4 | 7.5 | 11.7 | 6.8 | 10.4 | 5.2 | 7.7 | 7.1 | 8.5 | 7.0 | 10.2 |

| IHD (%) | 27.7 | 18.2 | 18.3 | 24.4 | 22.1 | 29.1 | 15.3 | 22.3 | 22.2 | 24.6 | 20.0 | 27.3 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 24.7 | 26.4 | 21.3 | 25.9 | 24.7 | 28.9 | 21.9 | 23.3 | 18.3 | 23.4 | 21.5 | 25.6 |

| CKD (%) | 14.9 | 15.5 | 13.1 | 9.1 | 13.7 | 13.9 | 10.2 | 14.6 | 12.6 | 14.3 | 12.3 | 12.5 |

| COPD (%) | 8.4 | 7.1 | 8.0 | 6.9 | 7.2 | 11.8 | 5.2 | 8.3 | 6.3 | 10.3 | 8.2 | 8.4 |

| Cancer (%) | 8.7 | 8.6 | 10.0 | 9.6 | 7.2 | 8.0 | 6.7 | 9.1 | 7.4 | 6.7 | 13.1 | 7.4 |

| Stroke (%) | 9.7 | 11.2 | 12.4 | 8.4 | 9.5 | 8.2 | 12.2 | 11.4 | 9.7 | 9.4 | 9.3 | 7.7 |

| Pulmonary disease (%) | 46.4 | 37.9 | 43.5 | 45.2 | 42.2 | 46.2 | 33.3 | 49.8 | 39.7 | 43.3 | 39.7 | 35.1 |

| Pneumonia (%) | 17.3 | 18.0 | 19.4 | 14.3 | 14.7 | 15.2 | 10.9 | 16.2 | 14.2 | 14.7 | 10.5 | 10.2 |

| Endpoints | ||||||||||||

| In‐hospital mortality, N (%) | 1323 (16.3) | 687 (18.2) | 2351 (30.4) | 304 (18.5) | 728 (14) | 179 (11.7) | 425 (17.5) | 460 (16.1) | 503 (13) | 145 (14.3) | 801 (24.7) | 329 (14.8) |

| 30 day mortality, N (%) | 351 (5.2) | 136 (4.4) | 259 (4.8) | 59 (4.4) | 220 (4.9) | 66 (4.9) | 75 (3.8) | 112 (4.7) | 141 (4.2) | 42 (4.8) | 133 (5.4) | 85 (4.5) |

| 1 year mortality, N (%) | 1569 (23.2) | 640 (20.7) | 1293 (24) | 275 (20.5) | 966 (21.7) | 298 (22) | 400 (20) | 493 (20.6) | 719 (21.4) | 214 (24.7) | 609 (24.9) | 389 (20.6) |

| 30 day readmission, N (%) | 637 (9.4) | 356 (11.5) | 619 (11.5) | 220 (16.4) | 525 (11.8) | 174 (12.9) | 260 (13) | 315 (13.2) | 399 (11.9) | 86 (9.9) | 284 (11.6) | 241 (12.7) |

| 1 year readmission, N (%) | 1663 (24.5) | 830 (26.8) | 1494 (27.7) | 407 (30.4) | 1167 (26.2) | 386 (28.6) | 562 (28.1) | 656 (27.4) | 882 (26.2) | 206 (23.8) | 690 (28.2) | 554 (29.3) |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HF, heart failure; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; IQR, interquartile range.

Collection of the data and HF hospitalization definitions were reported previously.13, 14 In brief, we documented hospital stay, hospital identificator, sex, age, co‐morbidities, statistical region of permanent residence, and date of death of all patients' HF hospitalizations. The HF hospitalization was defined as a hospitalization between 2004 and 2012 where HF was coded in any of the discharge diagnoses (ICD‐10 diagnosis codes: I50‐I50.9, I42‐I42.9, I11.0, I13.0, and I13.2).

No informed consent was required from the participants in this study, because the data were analysed and reported anonymously. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Slovenian National Medical Ethics Committee (Approval No. 55/10/14).

Definitions of study endpoints

Endpoints of the study were main HF hospitalization, first HF hospitalization, in‐hospital mortality during first HF hospitalization, mortality after first HF hospitalization (30 days and 1 year), and HF readmission after first HF hospitalization (30 days and 1 year). The main HF hospitalization was defined as a hospitalization, where HF was coded as the principal diagnosis of the hospitalization. The first HF hospitalization was defined in line with similar studies15, 16; if there was no report of hospitalization where HF was one of the discharge diagnoses in the previous 4 years, the index HF hospitalization was considered as the first one. Consequently, the data for first HF hospitalizations were available for the period 2008–12.

Statistical analysis

Numbers of annual age‐standardized and sex‐standardized main and first HF hospitalizations, in‐hospital, 30 day and 1 year mortality, and 30 day and 1 year HF readmissions per 100 000 population were calculated for each Slovenian statistical region. ANOVA was used to determine trends and mean yearly change in standardized HF hospitalization, mortality, and readmission rates. Rates were standardized using a direct standardization method for sex‐specific 5‐year age groups (20–24 to 95–99, and >100 years) and referenced to the 2011 Slovenian population from annual reports of the Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia.17

Different mixed effects were used to determine the effect of Slovenian statistical regions on mortality and HF readmission after first HF hospitalization, corrected for patients' demographics and co‐morbidities. In logistic regression models, we included statistical region, sex, age, year of admission, treatment in intensive care unit, and co‐morbidities as independent variables as a fixed effect and a hospital identificator as a random effect. By including the hospital identifier in logistic regression models as a random effect, we were able to correct for possible differences in care between hospitals. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals were calculated, where the region with the largest population and highest number of events (Osrednjeslovenska) was chosen as a reference. Statistical software R 3.2.2 (R Development Core Team) and R package lme418 were used for the analyses, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

During the study period, there were 2 430 748 hospitalizations due to any disease in Slovenia, 158 303 (6.5%) of those were with HF. After exclusion (638 residence outside Slovenia or missing region, 795 younger of 20 years, and 18 mismatch between date of death and admission), the final sample eventually included 156 859 HF hospitalizations (99.1%) of which 55 522 were main HF hospitalizations (35.4%) and 43 606 (47.8%) were first HF hospitalizations. Differences in patient characteristics between statistical regions are shown in Table 1.

Main and first heart failure hospitalization rates

Annual main HF hospitalization rates (per 100 000 population) were highest in Posavska statistical region (510 in 2004 and 511 in 2012) and lowest in Osrednjeslovenska statistical region (188 in 2004 and 195 in 2012), while national main HF hospitalization rates were 292 in 2004 and 270 in 2012. Similarly, first HF hospitalization rates were highest in Posavska statistical region (890 in 2008 and 709 in 2012) and lowest in Osrednjeslovenska statistical region (405 in 2008 and 399 in 2012), while overall national rates were 553 in 2008 and 515 in 2012 (Table 2). Over the study period, the main HF hospitalization rates for statistical regions have declined or remained unchanged (significant decline in Podravska, Jugovzhodna, and Obalno‐kraška regions, P < 0.05), while national rates have declined yearly by 3.6 (0.001) (Table 2). First HF hospitalization rates have declined or remained unchanged although no significant decline was seen. The national first HF hospitalization rates have declined yearly by 8.4 (0.083).

Table 2.

Regional main and first HF hospitalization rates per 100 000 population

| Region | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | Changea | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main HF hospitalizations | |||||||||||

| Slovenia | 292 | 297 | 303 | 292 | 282 | 281 | 279 | 273 | 270 | −3.6 | 0.001 |

| Pomurska | 393 | 444 | 468 | 419 | 408 | 419 | 365 | 366 | 364 | −9.3 | 0.039 |

| Podravska | 296 | 322 | 322 | 315 | 277 | 267 | 286 | 240 | 271 | −7.7 | 0.018 |

| Koroška | 241 | 327 | 320 | 290 | 308 | 300 | 284 | 361 | 287 | 3.7 | 0.420 |

| Savinjska | 314 | 302 | 296 | 301 | 300 | 289 | 317 | 327 | 268 | −1.3 | 0.597 |

| Zasavska | 435 | 359 | 433 | 359 | 366 | 427 | 378 | 394 | 364 | −3.7 | 0.420 |

| Posavska | 510 | 473 | 614 | 485 | 570 | 591 | 582 | 566 | 511 | 5.4 | 0.446 |

| Jugovzhodna Slovenija | 287 | 263 | 265 | 259 | 229 | 214 | 232 | 225 | 239 | −7.0 | 0.010 |

| Osrednjeslovenska | 188 | 185 | 187 | 187 | 188 | 180 | 184 | 179 | 195 | −0.1 | 0.928 |

| Gorenjska | 300 | 303 | 270 | 257 | 249 | 264 | 261 | 275 | 258 | −4.5 | 0.064 |

| Primorsko‐notranjska | 231 | 244 | 224 | 233 | 205 | 218 | 200 | 242 | 220 | −1.8 | 0.382 |

| Goriška | 347 | 385 | 423 | 412 | 410 | 386 | 341 | 334 | 331 | −6.8 | 0.162 |

| Obalno‐kraška | 335 | 337 | 324 | 348 | 302 | 314 | 324 | 276 | 297 | −6.2 | 0.022 |

| First HF hospitalizations | |||||||||||

| Slovenia | 553 | 550 | 553 | 541 | 515 | −8.4 | 0.083 | ||||

| Pomurska | 755 | 752 | 772 | 776 | 721 | −4.4 | 0.596 | ||||

| Podravska | 597 | 605 | 618 | 615 | 578 | −2.7 | 0.662 | ||||

| Koroška | 715 | 560 | 624 | 603 | 557 | −27.3 | 0.215 | ||||

| Savinjska | 537 | 551 | 558 | 545 | 511 | −5.7 | 0.387 | ||||

| Zasavska | 887 | 862 | 788 | 846 | 649 | −49.3 | 0.091 | ||||

| Posavska | 890 | 878 | 933 | 800 | 709 | −44.0 | 0.114 | ||||

| Jugovzhodna Slovenija | 531 | 541 | 550 | 556 | 523 | −0.1 | 0.992 | ||||

| Osrednjeslovenska | 405 | 419 | 402 | 383 | 399 | −4.9 | 0.290 | ||||

| Gorenjska | 480 | 478 | 502 | 501 | 471 | 0.4 | 0.942 | ||||

| Primorsko‐notranjska | 459 | 500 | 462 | 471 | 392 | −16.3 | 0.234 | ||||

| Goriška | 656 | 608 | 558 | 600 | 590 | −14.0 | 0.260 | ||||

| Obalno‐kraška | 505 | 474 | 543 | 457 | 455 | −11.6 | 0.397 | ||||

HF, heart failure.

Average yearly change in rates.

Mortality and heart failure readmissions

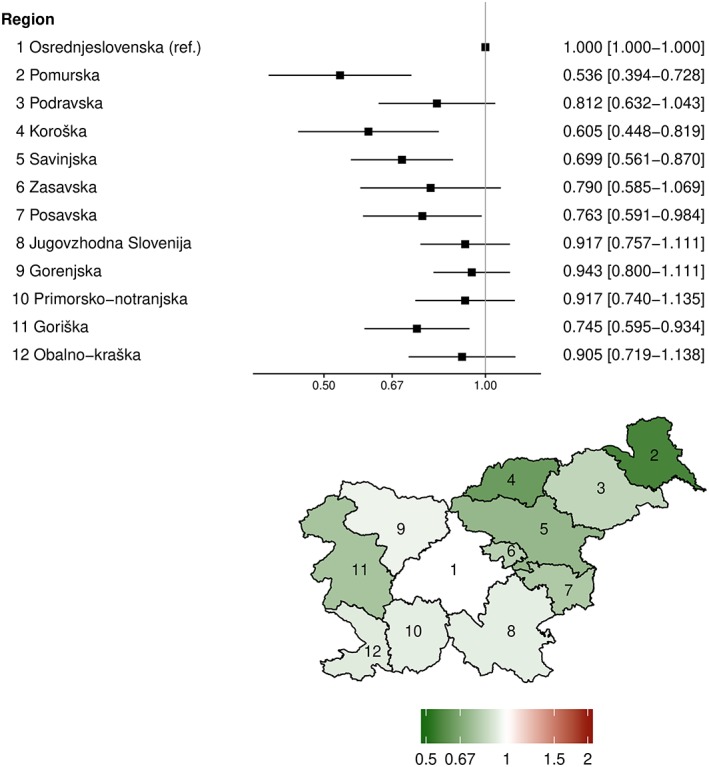

During first HF hospitalization, 8235 (18.9%) patients died, while of those that were discharged alive, 679 (3.9%) and 7865 (18.0%) died within 30 days and 1 year, respectively (Table 1). In‐hospital mortality was highest in Podravska statistical region and lowest in Zasavska statistical region (Table 1; Supporting Information, Figure S1 ). In multiple logistic regression, the OR for in‐hospital mortality were lowest in Pomurska, Koroška, Savinjska, Goriška, and Posavska (Figure 1 ). Among the included predictors, presence of cancer, stroke, and pneumonia had the highest odds for in‐hospital mortality (Supporting Information, Figure S2 ).

Figure 1.

Multiple logistic regression model for in‐hospital mortality. Results are shown as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals for each statistical region.

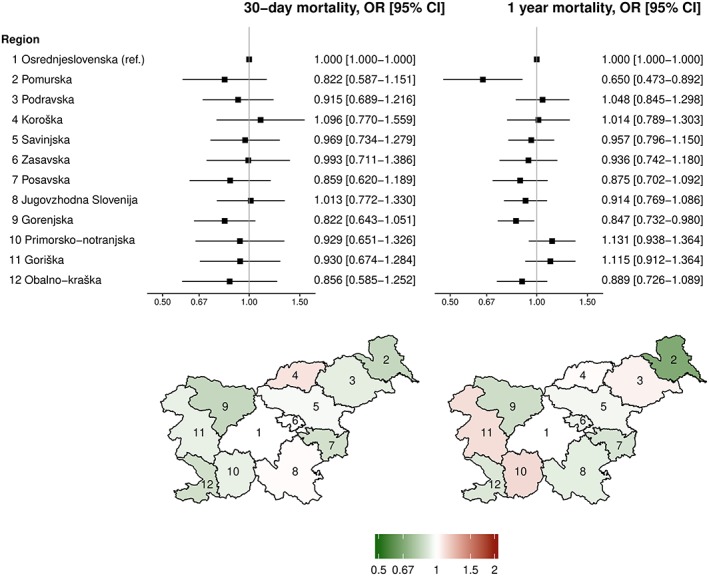

Annual 30 day and 1 year mortality rates after first HF hospitalization were highest in Zasavska and Posavska statistical regions and lowest in Osrednjeslovenska, Gorenjska, and Obalno‐kraška statistical regions (Table 3). In multiple logistic regression, the OR for 30 day and 1 year mortality were similar between Osrednjeslovenska and any other statistical region, except for Pomurska and Gorenjska, which had lower OR for 1 year mortality (0.650 and 0.847, respectively) (Figure 2 ). Among the included predictors, male sex, presence of myocardial infarction, chronic kidney disease, and cancer had the highest odds for 30 day or 1 year mortality after the first HF hospitalization (Supporting Information, Figure S3 ).

Table 3.

Standardized mortality rates per 100 000

| Region | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | Changea | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 days | |||||||

| Slovenia | 22.6 | 22.6 | 21.9 | 21.1 | 18.1 | −1.1 | 0.045 |

| Pomurska | 21.5 | 35.5 | 25.6 | 26.3 | 26.2 | 0 | 0.993 |

| Podravska | 22.9 | 24 | 20.5 | 24.5 | 14.2 | −1.7 | 0.249 |

| Koroška | 25.6 | 15.4 | 34.5 | 25.6 | 13.9 | −1.3 | 0.693 |

| Savinjska | 29.9 | 21.1 | 19.6 | 25.4 | 23.8 | −0.8 | 0.61 |

| Zasavska | 36.6 | 52.8 | 32.9 | 41.2 | 14.8 | −5.5 | 0.255 |

| Posavska | 34.8 | 19.3 | 22.5 | 31.7 | 23.2 | −1.1 | 0.672 |

| Jugovzhodna Slovenija | 31.2 | 21.2 | 28.5 | 18.6 | 12.6 | −4 | 0.077 |

| Osrednjeslovenska | 17.2 | 19.8 | 19.2 | 13.4 | 17.1 | −0.7 | 0.479 |

| Gorenjska | 16.6 | 18.7 | 21.1 | 17.6 | 15.9 | −0.2 | 0.772 |

| Primorsko‐notranjska | 22 | 24.3 | 21.9 | 10.5 | 13.2 | −3.2 | 0.094 |

| Goriška | 24.1 | 21.6 | 18 | 27.9 | 27.1 | 1.3 | 0.408 |

| Obalno‐kraška | 18.8 | 18.1 | 23.2 | 21 | 14.2 | −0.6 | 0.629 |

| 1 year | |||||||

| Slovenia | 99 | 102 | 102 | 102 | 89 | −2 | 0.315 |

| Pomurska | 126 | 151 | 133 | 121 | 107 | −6.9 | 0.215 |

| Podravska | 96 | 100 | 105 | 117 | 93 | 1.1 | 0.761 |

| Koroška | 106 | 81 | 114 | 123 | 99 | 2.7 | 0.663 |

| Savinjska | 107 | 109 | 98 | 113 | 92 | −2.6 | 0.411 |

| Zasavska | 168 | 176 | 156 | 170 | 117 | −10.8 | 0.167 |

| Posavska | 128 | 146 | 165 | 147 | 107 | −4 | 0.636 |

| Jugovzhodna Slovenija | 92 | 95 | 106 | 104 | 78 | −2 | 0.651 |

| Osrednjeslovenska | 80 | 84 | 79 | 71 | 75 | −2.2 | 0.185 |

| Gorenjska | 82 | 90 | 101 | 96 | 87 | 1.5 | 0.587 |

| Primorsko‐notranjska | 104 | 121 | 87 | 89 | 72 | −9.7 | 0.089 |

| Goriška | 127 | 96 | 97 | 112 | 117 | −0.4 | 0.947 |

| Obalno‐kraška | 95 | 85 | 102 | 84 | 66 | −5.7 | 0.208 |

Average yearly change in rates.

Figure 2.

Multiple logistic regression models for 30 day and 1 year mortality. Results are shown as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals for each statistical region.

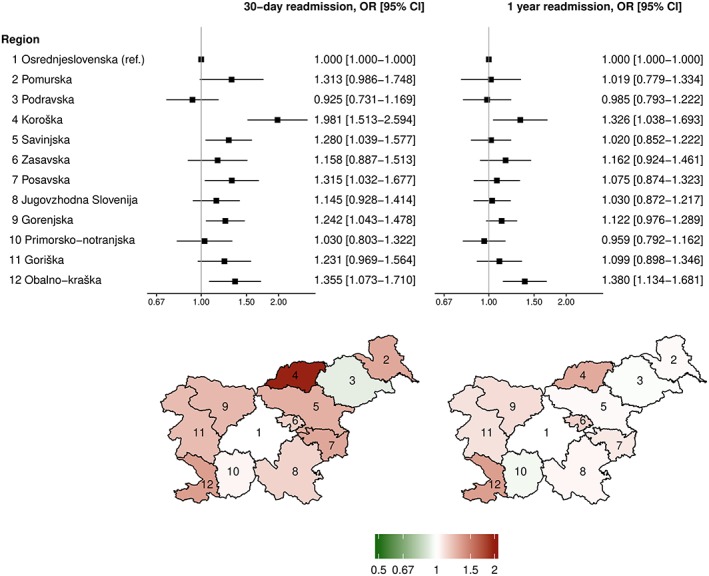

After first HF hospitalization, 4119 (9.4%) and 9499 (21.8%) of patients had 30 day and 1 year HF readmission, respectively. Annual 30 day and 1 year readmission rates after first HF hospitalization were highest in Zasavska and Posavska statistical regions, while lowest in Osrednjeslovenska statistical region (Table 4). In multiple logistic regression, the OR for 30 day and 1 year readmission were similar between Osrednjeslovenska and any other statistical region, except for Koroška and Obalno‐kraška, which had higher OR for 30 day and 1 year readmission (Figure 3 ). Among the included predictors, male sex, presence of cancer, chronic kidney disease, pulmonary disease, myocardial infarction, and diabetes mellitus had the highest odds for 30 day or 1 year readmission after the first HF hospitalization (Supporting Information, Figure S4 ).

Table 4.

Standardized readmission rates per 100 000

| Region | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | Changea | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 days | |||||||

| Slovenia | 47.8 | 48.3 | 54.8 | 54.9 | 49.2 | 0.9 | 0.484 |

| Pomurska | 61.0 | 53.7 | 79.5 | 80.0 | 77.9 | 6.0 | 0.122 |

| Podravska | 43.4 | 41.4 | 55.9 | 56.9 | 41.6 | 1.2 | 0.699 |

| Koroška | 101.9 | 85.2 | 92.7 | 58.4 | 69.8 | −9.1 | 0.088 |

| Savinjska | 50.4 | 52.3 | 57.8 | 58.5 | 52.7 | 1.1 | 0.423 |

| Zasavska | 94.9 | 103.9 | 96.2 | 100.8 | 65.6 | −6.2 | 0.250 |

| Posavska | 84.5 | 69.2 | 103.0 | 110.7 | 80.8 | 3.4 | 0.601 |

| Jugovzhodna Slovenija | 59.4 | 55.6 | 57.4 | 62.8 | 59.7 | 0.8 | 0.432 |

| Osrednjeslovenska | 26.5 | 34.8 | 34.8 | 30.2 | 31.5 | 0.5 | 0.697 |

| Gorenjska | 43.7 | 46.2 | 53.6 | 63.6 | 44.1 | 1.8 | 0.577 |

| Primorsko‐notranjska | 21.5 | 41.2 | 29.6 | 48.2 | 51.8 | 6.8 | 0.075 |

| Goriška | 51.4 | 54.0 | 46.6 | 52.3 | 58.3 | 1.2 | 0.441 |

| Obalno‐kraška | 61.0 | 43.3 | 56.2 | 48.8 | 53.0 | −1.0 | 0.694 |

| 1 year | |||||||

| Slovenia | 143 | 144 | 155 | 155 | 4.8 | 0.086 | |

| Pomurska | 176 | 194 | 226 | 238 | 21.8 | 0.014 | |

| Podravska | 134 | 133 | 154 | 164 | 11.3 | 0.055 | |

| Koroška | 238 | 163 | 202 | 159 | −19.7 | 0.311 | |

| Savinjska | 142 | 147 | 163 | 162 | 7.7 | 0.072 | |

| Zasavska | 269 | 261 | 256 | 243 | −8.1 | 0.021 | |

| Posavska | 219 | 237 | 288 | 237 | 10.4 | 0.548 | |

| Jugovzhodna Slovenija | 144 | 156 | 145 | 182 | 10.6 | 0.243 | |

| Osrednjeslovenska | 103 | 110 | 109 | 99 | −1.3 | 0.667 | |

| Gorenjska | 117 | 128 | 147 | 169 | 17.5 | 0.011 | |

| Primorsko‐notranjska | 87 | 141 | 105 | 138 | 11.7 | 0.417 | |

| Goriška | 179 | 171 | 153 | 146 | −11.6 | 0.016 | |

| Obalno‐kraška | 176 | 127 | 173 | 137 | −7.3 | 0.624 |

Average yearly change in rates.

Figure 3.

Multiple logistic regression models for 30 day and 1 year readmission. Results are shown as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals for each statistical region.

Discussion

The national trends in main HF hospitalization, first HF hospitalization, 30 day mortality, and 1 year mortality rates have decreased, while 30 day and 1 year readmission rates have increased. While most of the statistical regions followed national trends, there were some exceptions. In terms of overall HF hospitalization, mortality, and readmission rates, differences between regions were seen. Zasavska, Posavska, and Prekmurska statistical regions had the highest HF burden in terms of standardized hospitalization, mortality, and readmission rates. When considering each individual patient, no important differences in mortality and readmission endpoints between statistical regions were present. The most important predictors for mortality and readmission were sex, age, and co‐morbidities, such as cancer, myocardial infarction, stroke, chronic kidney disease, and pulmonary disease.

In our study, the highest standardized rates were shown in the regions with the lowest socio‐economic status19 and those with high prevalence of CV risk factors,20 while regions with high HF hospitalization rates had also high mortality and readmission rates. Studies from other countries also reported differences in regional HF hospitalization rates. Casper et al.11 showed that most of the HF hospitalization burden came from specific areas in the USA with the highest prevalence of risk factors for CV disease. Furthermore, Ogunniyi et al.,10 in the study in Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized due to HF in Tennessee catchment area, reported that counties with higher HF hospitalization rates were in general those with lower primary care physician to Medicare beneficiaries ratio and that HF hospitalization rates were higher in rural counties. On the other hand, European study investigating potentially avoidable hospitalizations in the Spanish regions of Castile and Leon found the opposite.21 Patients from different countries have significant differences in HF characteristics and in treatment outcomes as highlighted in this subanalysis of CIBIS‐ELD trial.22 From data presented in our study, we can stipulate that such differences might occur between different regions inside countries as well.

Patient's demographics and co‐morbidities have a crucial role in the development of readmission and mortality. While it has been shown that women develop HF later than men,23 men have higher mortality when compared with women of equal age, as shown in our study. Not surprisingly, co‐morbidities, such as cancer, myocardial infarction, stroke, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes, are associated with higher mortality, while arterial hypertension and ischaemic heart disease were associated with lower mortality. An interesting result previously reported in German study showed that patients hospitalized with arterial hypertension and previous myocardial infarction had lower mortality.3 We believe that patients with arterial hypertension represent overall healthier patients with fewer other co‐morbidities, whereas patients hospitalized with advanced or severe HF are frequently hypotensive. In recent years, there have been a decreasing trends of mortality after HF hospitalization, consistent with other European countries.24, 25 In Slovenia, general trend of reducing HF mortality could be explained by the reduction of CV risk factors26 and improvement in the care of HF patients.27 Even though the adherence to guidelines in the managing of HF is improving, there is still room for improvement and better detection of patients at risk.28, 29, 30

Proportions of in‐hospital mortality and outcomes after discharge for first HF hospitalizations have shown large regional variations. Also, standardized mortality and readmission rates were different between regions, and large differences in trends between regions were observed. Even though there were significant differences in standardized HF hospitalization, mortality, and readmission rates between statistical regions, each comparable patient from different regions had the same odds for mortality or readmission endpoints. Differences in standardized rates might reflect the differences in patient's characteristics between regions. This was tested by the use of multiple logistic regression modelling where factors that influence the outcomes are included. The OR for each variable therefore reflects the difference in similar patients—same sex, age, admission year, and with the same co‐morbidities.31 Analysis showed most regional differences in prevalence of CV risk factors, co‐morbidities, and demographics were not influenced. Furthermore, by including hospital identifier as a random effect to correct the model for possible hospital specific properties that influence the outcomes also did not influence the findings.32 Because the majority of the patients in a region were hospitalized in a regional general hospital, the inclusion of the random effect is important to minimize the confounding on regional effects. Still, there are some possible region‐specific relevant factors with effect on outcomes. In the models, we could not include socio‐economic status of the patients nor could we correct for the possible differences in HF severity, access to health care services, admission policies in hospitals, referrals from primary care, and outpatient management.

Heart failure is one of the most important reasons for health expenditure6 and is the most common cause for hospitalization in Slovenia.1 HF is a condition for which effective outpatient care and interventions can potentially prevent the need for hospitalization, prevent readmissions, and complications or more severe disease.4, 33 Many of the risk factors for HF (e.g. hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and acute myocardial infarction) are largely preventable with a combination of appropriate prevention programmes and access to quality medical care. From the data presented in this study, we can presume that reasons for higher mortality rates are mostly due to high prevalence of HF hospitalizations and difference in patients' demographics and co‐morbidity profiles. The regions that had high mortality rates overlap with those with high HF hospitalization rates, while risk‐adjusted OR between regions are comparable. This highlights the need for targeted preventive programmes in regions with the highest HF burden.

Strengths and limitations

This study on a national level provided with important data on regional variability of HF hospitalizations, mortality, and readmission. We were able to analyse ‘real life’ patients with HF and compare it between statistical regions. To our knowledge, this is the first study that evaluated regional differences in HF hospitalizations and outcomes after HF hospitalization in such a comprehensive way. Our results highlight regions with the highest HF burden and the need for preventive programmes in order to reduce the differences between regions.

There were also limitations to this study. Firstly, the accuracy of the National Hospital Discharge Registry relies on the data entered by the contributing hospitals. However, all hospitals are using standardized methodology, and coding practices during the study period remained unchanged. Even though no validation studies into this database exist, a meta‐analysis of several similar registries has concluded that the data in administrative registries for HF are reliable.34 Secondly, the registry does not record the use of medications; therefore, in the multiple logistic regression analysis, we were unable to control for prescribed medications. Thirdly, because the registry does not specify whether an individual diagnosis is recorded for the first time, we have used an observational period of 4 years to define the first HF hospitalization. Some patients were therefore incorrectly identified as having first HF hospitalization, but considering the frequency of HF hospitalizations, it is likely that this was only a small or even negligible proportions of patients. Similar methodology has already been used24, 35; thus, we believe that the use of such methodology provided with accurate analysis.

Conclusions

In this observational, epidemiological study of a nationwide HF hospitalization database, we found that even though there were significant differences between regions in standardized HF hospitalization, mortality, and readmission rates, there were no differences between regions in odds for mortality and readmission for an individual patient. High mortality rates correlated with high prevalence of HF hospitalizations, which highlights the need for targeted preventive programmes in regions with the largest burden of HF.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the project (Epidemiology of heart failure in Slovenia: prevalence, hospitalizations and mortality; J3‐7405) that was financially supported by Slovenian Research Agency. D.O. received research fellowship from the Slovenian Research Agency (grant no. 630‐84/2015‐1).

Supporting information

Figure S1. In‐hospital mortality percentage per statistical region. 1 – Osrednjeslovenska, 2 – Prekmurska, 3 – Podravska, 4 – Koroška, 5 – Savinjska, 6 – Zasavska, 7 – Posavska, 8 – Jugovzhodna Slovenija, 9 – Gorenjska, 10 – Primorsko‐notranjska, 11 – Goriška, 12 – Obalno‐kraška.

Figure S2. Multiple logistic regression models for in‐hospital mortality: Demographics and comorbidities. Results are shown as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. *per 10 year increase, **per 1‐year increase. Abbreviations: COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ICU – intensive care unit.

Figure S3. Multiple logistic regression models for 30‐day and 1‐year mortality: Demographics and comorbidities. Results are shown as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. *per 10 year increase, **per 1‐year increase. Abbreviations: COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ICU – intensive care unit.

Figure S4. Multiple logistic regression models for 30‐day and 1‐year readmission: Demographics and comorbidities. Results are shown as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. *per 10 year increase, **per 1‐year increase. Abbreviations: COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ICU – intensive care unit.

Omersa, D. , Erzen, I. , Lainscak, M. , and Farkas, J. (2019) Regional differences in heart failure hospitalizations, mortality, and readmissions in Slovenia 2004–2012. ESC Heart Failure, 6, 965–974. 10.1002/ehf2.12488.

References

- 1. National Institute of Public Health . Statistical health yearbook 2013. Ljubljana: National Institute of Public Health; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Townsend N, Nichols M, Scarborough P, Rayner M. Cardiovascular disease in Europe—epidemiological update 2015. Eur Heart J 2015; 36: 2667–2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ohlmeier C, Mikolajczyk R, Frick J, Prütz F, Haverkamp W, Garbe E. Incidence, prevalence and 1‐year all‐cause mortality of heart failure in Germany: a study based on electronic healthcare data of more than six million persons. Clin Res Cardiol 2015; 104: 688–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Falk V, González‐Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GMC, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P, Authors/Task Force Members , Document Reviewers . 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2016; 18: 891–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Farmakis D, Simitsis P, Bistola V, Triposkiadis F, Ikonomidis I, Katsanos S, Bakosis G, Hatziagelaki E, Lekakis J, Mebazaa A, Parissis J. Acute heart failure with mid‐range left ventricular ejection fraction: clinical profile, in‐hospital management, and short‐term outcome. Clin Res Cardiol 2016; 106: 359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cook C, Cole G, Asaria P, Jabbour R, Francis DP. The annual global economic burden of heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2014; 171: 368–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ponikowski P, Anker SD, AlHabib KF, Cowie MR, Force TL, Hu S, Jaarsma T, Krum H, Rastogi V, Rohde LE, Samal UC, Shimokawa H, Budi Siswanto B, Sliwa K, Filippatos G. Heart failure: preventing disease and death worldwide. ESC Heart Fail 2014; 1: 4–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crespo‐Leiro MG, Anker SD, Maggioni AP, Coats AJ, Filippatos G, Ruschitzka F, Ferrari R, Piepoli MF, Delgado Jimenez JF, Metra M, Fonseca C, Hradec J, Amir O, Logeart D, Dahlström U, Merkely B, Drozdz J, Goncalvesova E, Hassanein M, Chioncel O, Lainscak M, Seferovic PM, Tousoulis D, Kavoliuniene A, Fruhwald F, Fazlibegovic E, Temizhan A, Gatzov P, Erglis A, Laroche C, Mebazaa A, on behalf of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) . European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Long‐Term Registry (ESC‐HF‐LT): 1‐year follow‐up outcomes and differences across regions. Eur J Heart Fail 2016; 18: 613–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bobak M, Marmot M. East‐West mortality divide and its potential explanations: proposed research agenda. BMJ 1996; 312: 421–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ogunniyi MO, Holt JB, Croft JB, Nwaise IA, Okafor HE, Sawyer DB, Giles WH, Mensah GA. Geographic variations in heart failure hospitalizations among Medicare beneficiaries in the Tennessee catchment area. Am J Med Sci 2012; 343: 71–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Casper M, Nwaise I, Croft JB, Hong Y, Fang J, Greer S. Geographic disparities in heart failure hospitalization rates among Medicare beneficiaries. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 55: 294–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen J, Normand S‐LT, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. National and regional trends in heart failure hospitalization and mortality rates for Medicare beneficiaries, 1998‐2008. JAMA 2011; 306: 1669–1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Omersa D, Farkas J, Erzen I, Lainscak M. National trends in heart failure hospitalization rates in Slovenia 2004‐2012. Eur J Heart Fail 2016; 18: 1321–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Omersa D, Lainscak M, Erzen I, Farkas J. Mortality and readmissions in heart failure: an analysis of 36,824 elderly patients from Slovenian national hospitalization database. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2016; 128: 512–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Barasa A, Schaufelberger M, Lappas G, Swedberg K, Dellborg M, Rosengren A. Heart failure in young adults: 20‐year trends in hospitalization, aetiology, and case fatality in Sweden. Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schmidt M, Ulrichsen SP, Pedersen L, Bøtker HE, Sørensen HT. Thirty‐year trends in heart failure hospitalization and mortality rates and the prognostic impact of co‐morbidity: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Eur J Heart Fail 2016; 18: 490–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia . Population by large and 5‐year age groups and sex, statistical regions, Slovenia, annually [Internet]. http://pxweb.stat.si/pxweb/Dialog/varval.asp?ma=05C2002E&ti=&path=../Database/Demographics/05_population/10_Number_Population/10_05C20_Population_stat_regije/&lang=1 (2 Dec 2015).

- 18. Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed‐effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 2015; 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 19. National Institute of Public Health . Statistical Portrait of Slovene Regions 2016. Ljubljana: National Institute of Public Health; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zaletel‐Kragelj L, Erzen I, Fras Z. Interregional differences in health in Slovenia. I. Estimated prevalence of selected cardiovascular and related diseases. Croat Med J 2004; 45: 637–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Borda‐Olivas A, Fernández‐Navarro P, Otero‐García L, Sanz‐Barbero B. Rurality and avoidable hospitalization in a Spanish region with high population dispersion. Eur J Public Health 2013; 23: 946–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chavanon M‐L, Inkrot S, Zelenak C, Tahirovic E, Stanojevic D, Apostolovic S, Sljivic A, Ristic AD, Matic D, Loncar G, Veskovic J, Zdravkovic M, Lainscak M, Pieske B, Herrmann‐Lingen C, Düngen HD. Regional differences in health‐related quality of life in elderly heart failure patients: results from the CIBIS‐ELD trial. Clin Res Cardiol 2017; 106: 645–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meyer S, Brouwers FP, Voors AA, Hillege HL, de Boer RA, Gansevoort RT, van der Harst P, Rienstra M, van Gelder IC, van Veldhuisen DJ, van Gilst WH, van der Meer P. Sex differences in new‐onset heart failure. Clin Res Cardiol 2015; 104: 342–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jhund PS, Macintyre K, Simpson CR, Lewsey JD, Stewart S, Redpath A, Chalmers JW, Capewell S, McMurray JJ. Long‐term trends in first hospitalization for heart failure and subsequent survival between 1986 and 2003: a population study of 5.1 million people. Circulation 2009; 119: 515–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Meinertz T, Diegeler A, Stiller B, Fleck E, Heinemann MK, Schmaltz AA, Vestweber M, Bestehorn K, Beckmann A, Hamm C, Cremer J. German Heart Report 2013. Clin Res Cardiol 2015; 104: 112–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Artnik B, Bajt M, Bilban M, Borovničar A, Brguljan Hitij J, Djomba JK, Fras Z, Hlastan‐Ribič C, Klanšček HJ, Kelšin N, Kofol‐Bric T. Zdravje in vedenjski slog prebivalcev Slovenije: trendi v raziskavah CINDI 2001–2004‐2008. Ljubljana: Inštitut za varovanjE zdravja RS; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lainscak M, Horvat A, Keber I. The management of patients with heart failure in a Slovenian community hospital: what has changed between 1997 and 2000? Wien Klin Wochenschr 2003; 115: 334–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cowie MR, Anker SD, Cleland JGF, Felker GM, Filippatos G, Jaarsma T, Jourdain P, Knight E, Massie B, Ponikowski P, López‐Sendón J. Improving care for patients with acute heart failure: before, during and after hospitalization. ESC Heart Fail 2014; 1: 110–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sato A, Yoshihisa A, Kanno Y, Takiguchi M, Miura S, Shimizu T, Nakamura Y, Yamauchi H, Owada T, Sato T, Suzuki S, Oikawa M, Yamaki T, Sugimoto K, Kunii H, Nakazato K, Suzuki H, Saitoh SI, Takeishi Y. Associations of dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitors with mortality in hospitalized heart failure patients with diabetes mellitus. ESC Heart Fail 2015; 3: 77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Martens P, Beliën H, Dupont M, Mullens W. Insights into implementation of sacubitril/valsartan into clinical practice. ESC Heart Fail 2018; 5: 275–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Daniels MJ, Gatsonis C. Hierarchical generalized linear models in the analysis of variations in health care utilization. J Am Stat Assoc 1999; 94: 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Krumholz HM, Wang Y, Mattera JA, Wang Y, Han LF, Ingber MJ, Roman S, Normand SLT. An administrative claims model suitable for profiling hospital performance based on 30‐day mortality rates among patients with heart failure. Circulation 2006; 113: 1693–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McDonagh TA, Blue L, Clark AL, Dahlström U, Ekman I, Lainscak M, McDonald K, Ryder M, Strömberg A, Jaarsma T, European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Association Committee on Patient Care . European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Association standards for delivering heart failure care. Eur J Heart Fail 2011; 13: 235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McCormick N, Lacaille D, Bhole V, Avina‐Zubieta JA. Validity of heart failure diagnoses in administrative databases: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS One 2014; 9: e104519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Parén P, Schaufelberger M, Björck L, Lappas G, Fu M, Rosengren A. Trends in prevalence from 1990 to 2007 of patients hospitalized with heart failure in Sweden. Eur J Heart Fail 2014; 16: 737–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. In‐hospital mortality percentage per statistical region. 1 – Osrednjeslovenska, 2 – Prekmurska, 3 – Podravska, 4 – Koroška, 5 – Savinjska, 6 – Zasavska, 7 – Posavska, 8 – Jugovzhodna Slovenija, 9 – Gorenjska, 10 – Primorsko‐notranjska, 11 – Goriška, 12 – Obalno‐kraška.

Figure S2. Multiple logistic regression models for in‐hospital mortality: Demographics and comorbidities. Results are shown as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. *per 10 year increase, **per 1‐year increase. Abbreviations: COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ICU – intensive care unit.

Figure S3. Multiple logistic regression models for 30‐day and 1‐year mortality: Demographics and comorbidities. Results are shown as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. *per 10 year increase, **per 1‐year increase. Abbreviations: COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ICU – intensive care unit.

Figure S4. Multiple logistic regression models for 30‐day and 1‐year readmission: Demographics and comorbidities. Results are shown as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. *per 10 year increase, **per 1‐year increase. Abbreviations: COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ICU – intensive care unit.