Abstract

Purpose

The main objective of this study was to investigate abuse of residents with either dementia or Alzheimer’s disease in long-term care settings, to identify facilitators and barriers surrounding implementation of systems to prevent such occurrences, and to draw conclusions on combating the issue of abuse.

Patients and methods

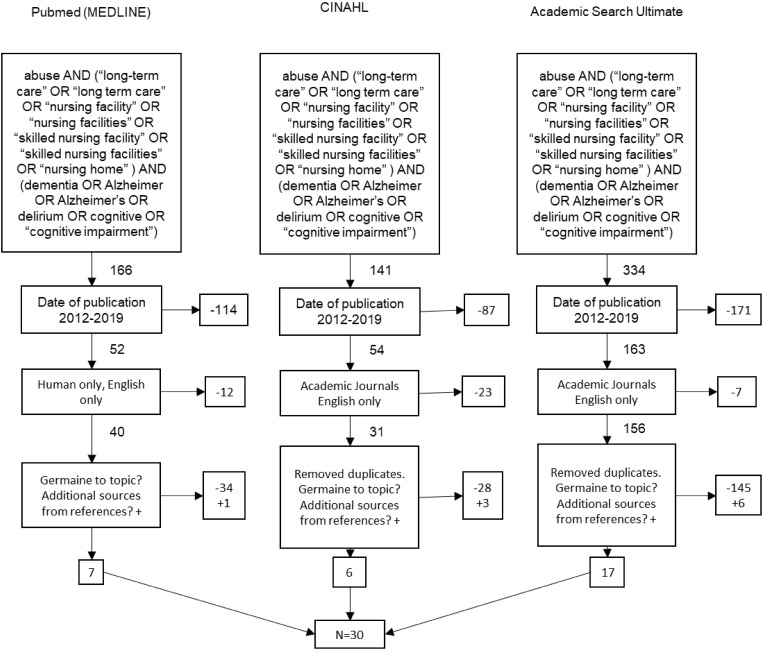

A systematic review was conducted using the Medline, CINAHL, and Academic Search Ultimate databases. With the use of key terms via Boolean search, 30 articles were obtained which were determined to be germane to research objectives. The review was conducted and structured based on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Results

Residents with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease are at greater risk of abuse. The growing population could increase this problem exponentially. The most common facilitators were the introduction of policies/programs in the facility, education, and working conditions. The most cited barriers were poor training, lack of research, and working conditions in the long-term care setting.

Conclusion

The examples given would be useful in minimizing the potential for abuse in the long-term care setting. Leadership can take an active role in the prevention of abuse of the elderly through their actions, education of employees, and changes in the work environment.

Keywords: exploitation, nursing facility, skilled nursing, nursing home

Introduction

The presence of abuse in the long-term care (LTC) environment is a reality that needs to be addressed and prevented. It is believed that between one and two million US citizens over the age of 65 have either been mistreated, exploited, or even injured by a caregiver.1 The statistics show that most abuse, including physical and financial, is poorly reported.1 It is estimated that for every one case of elder abuse which is reported to authorities, five go unreported.2 Those individuals with some form of dementia or Alzheimer’s are at an even higher risk of abuse and neglect, and with the number of Alzheimer’s cases expected to increase exponentially due to the aging of our population, these numbers are more than likely to continue to increase unless a solution is not implemented.1 Forty-four percent of the elderly population residing in a long-term care setting have been abused in some form or fashion, and it is estimated that only around 7% of the cases are reported to authorities.1

Background

LTC facilities have very specific laws which apply to their residents and their “right to be free” from abuse, neglect, or exploitation.3,4 The LTC setting offers a broad range of services which include health care, personal care, and supportive services that are suited to meet the needs of residents with cognitive deficits, physical/chronic illnesses, and some mental disabilities. Abuse is defined as the willful infliction of injury, unreasonable confinement, intimidation, or punishment of an LTC resident.3,4 This abuse can result in physical harm, pain, mental anguish, or deprivation of an individual.3,4 It can also consist of verbal, psychological, physical, sexual, or financial abuse.3–5 Abuse can come from many different sources, including family members, informal and formal caregivers, acquaintances, or other residents.5 Neglect is the failure of a caregiver, facility, employees, or service providers to provide goods and services which are necessary to avoid physical harm, pain, mental anguish, or emotional stress.3 Neglect does not have to be a willful act. Conversely, abuse is considered a willful act by the perpetrator. Exploitation refers to the right of the resident to not have their property, assets, or resources used without their express permission.2 This generally refers to the use of the elder’s assets for the benefit of someone else without their knowledge.

It is known that uncooperative and aggressive residents increase the risk of abuse, which is often the case with those suffering from Alzheimer’s or other dementias.6 Training that increases staff skills when dealing with residents that have cognitive deficits can give staff more expertise in recognizing and dealing with challenging ethical issues, including the reporting process.7 Increased competence in dementia and Alzheimer’s disease processes could help promote staff awareness and better understanding of risk factors associated with physical abuse of long-term care residents.8–11 While there are many opportunities to decrease abuse, items of concern such as understaffing, underappreciating staff, and a complete lack of training can lead to abuse in the long-term care setting.9,11

Significance

It is understood that most nursing facility staff members have an awareness that there is an issue surrounding abuse. It is postulated that more than 50% of long-term care staff members polled admitted to treating elders poorly, either by means of physical violence, mental abuse, or neglect.7 This literature review focuses on the topic of abuse of those with Alzheimer’s or dementia in the long-term care setting and seeks to educate the reader on methods discovered to detect and prevent elder abuse. We delve into the successes of some programs and what has been developed to resolve this increasingly difficult problem, in addition to identifying some of the barriers to success in ensuring the quality of care throughout the LTC environment. High-risk factors will also be identified which could lead to abuse by caregivers as well as interventions. This review reaffirms the importance of ensuring residents receive the quality of care in the long-term care setting by means of proper assessments and training of staff.

Materials And Methods

Design

This study used a systematic review of peer-reviewed articles found in indexed databases. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) guidelines were used to ensure consistent and precise reporting of results. The initial search was conducted on September 10, 2018, while the final search was completed on May 20, 2019, using three databases: Academic Search Ultimate, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and PubMed (MEDLINE). A complex accumulation of search terms were initially chosen to locate an appropriate amount of resources, but this led to an overabundance of results, requiring a more narrowed search approach to be conducted. The authors examined the search results from the databases using only the most commonly revealed keywords. This led to the three-string Boolean search which is included in Figure 1. A review of articles found in the citations led to additional resources which met the inclusion criteria also being included.

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic review flow diagram.

Inclusion Criteria

All authors individually reviewed the articles from the search, determined germane literature, and summarized themes. Inclusion criteria included English-language and peer-reviewed articles published by academic journals or universities between January 1, 2012, and April 30, 2019. For inclusion, articles must have explored the issue of abuse in the long-term care setting, whether physically, mentally, or financially. Articles could reference specific incidents or prior research alike.

Exclusion Criteria

Articles were only incorporated if deemed germane by all authors. Trade industry reports and poster presentations without a clear, scientific format, and a peer review process were excluded. Articles related to employee abuse were not included. Articles that only mentioned the symptoms of dementia or Alzheimer’s or described how to combat the onset of these diseases were also not included. Articles that did not mention some form of abuse of those with either Alzheimer’s or a form of dementia in the long-term care setting were excluded from qualitative analysis. Bias was not considered when reviewing the research involved. The final yield of articles after using exclusion criteria was then analyzed for consensus among all authors for final inclusion. When analyzed, this sample yielded a kappa statistic (k=1), showing strong interrater reliability.

Data Analysis

Narrative summaries related to factors affecting abuse within the long-term care setting were extracted from each article. The authors focused on the abuse of residents with some form of dementia or Alzheimer’s. Summaries were grouped into larger recurring themes that can be classified as facilitators or barriers to success in preventing abuse. The themes chosen were by consensus of the authors. Themes chosen were agreed upon due to their overall summary of the facilitators and barriers extracted. These themes were then divided into two affinity matrix tables, one for facilitators and one for barriers. Each table documents the themes, their citation occurrence, their frequency sum, and frequency percentage.

Results

Study Selection

The article selection process is defined in the PRISMA flow diagram. The initial search protocol of 3 databases yielded 641 articles, including duplicates. Subsequently, 414 articles were then excluded for not meeting the predetermined inclusion requirements. Furthermore, another 207 articles were eliminated as either duplicates or not providing relevance to the topic, leaving 20 articles for review. After further distinctions were made within the search, and an in-depth analysis of citations among these 20 articles, an additional 10 articles met the inclusion requirements. A total of 30 articles were used for qualitative analysis. A summary of the articles chosen for inclusion is included in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary Of Article Findings

| Author Last Name | Aim | Sample/Settings | Method | Assessment Tool | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young/August 2018 [12] | Determining risk factors that can contribute to elder abuse by caregivers and how to prevent and provide treatment to reduce elder abuse. | Existing research/previous studies. | Existing research/previous studies. | Asking patients questions. | Vital for case managers to assess patients for signs of abuse. Do not rely on just asking the patient but investigating too. |

| Rose/June 2018 [13] | Preventing the mistreatment or neglect of long-term care (LTC) residents and noticing the signs of abuse is a concern for any risk manager or organizational leader. | 1.4 million people are living in 17,000 US nursing homes and an additional 7 million receive assistance with activities of daily living (CDC). | Documenting the abuse and inform the appropriate personnel at the LTC facility. | Interviews with patients and staff members. | The best way to prevent abuse is to look for the signs of abuse and listening to the patients. |

| Caspi/May 2018 [14] | Makes first steps towards bridging the major gap in research and practice. | Deaths of 105 elders pertaining to resident-to-resident incidents in long-term care homes. | Use of publicly available information to determine practical patterns. | Mostly newspaper articles and death review reports. | More deaths occurred from resident-to-resident altercations (RRA) inside bedrooms. Findings identified a series of patterns and vulnerability areas for prevention of death. Newly admitted residents (less than 3 months at facility) are more prone to involvement in RRA. Policies and procedures related to roommate assignment needs to be regularly examined by administration and nursing staff. |

| Jacobsen/September 2017 [15] | To investigate which factors hindered or facilitated staff awareness related to confidence building initiatives based on person-centered care, as an alternative to restraint in residents with dementia in nursing homes. | Two-day seminar and monthly coaching sessions for six months, targeted nursing staff in 24 nursing homes in Western Norway. | A mixed-method design combining quantitative and qualitative methods. The qualitative data were collected through ethnographic fieldwork, qualitative interviews, and analysis of 84 reflection notes. | P-CAT (Person-centered Care Assessment Tool) and QPS-Nordic (The General Nordic questionnaire for psychological and social factors at work). | Leadership is the most important factor promoting staff awareness and person-centered care. Staff must be educated, but leadership involvement is key in implementation of any program. |

| Wangmo/January 2017 [16] | To find solutions to help prevent elder abuse. | 3 nursing homes, 1 inpatient geriatric center, and 1 regional home care provider. 23 participants were male between 23 and 61 years of age with an average age of 43.6 years. 6 were nursing assistants, 6 were nursing care professionals, and 11 were qualified nurses. The work experience average was 19.4 years. 12 from the 3 nursing homes, 7 from inpatient center, and 4 from the home health care provider. | Face-to-face interviews with 23 nursing care providers between April 2014 and Dec 2014. Interviews were conducted by post-doctorate scholars with a background in philosophy. | T-test for independent observations. | Facilities need to hire more qualified staff, so abuse can be recognized and have appropriate staff to patient ratios. |

| Rosen/January 2017 [17] | Identifying common staff responses regarding resident-to-resident elder mistreatment or abuse. | 282 certified nursing assistants (CNAs) in 5 urban area nursing homes. | Study was performed in 5 large, not-for-profit, urban nursing homes in New York, based off interviews, a convenience sample of 282 certified nurse assistants (CNAs) who worked the day shift (28.1% of the total CNA workforce at these nursing homes). |

Interviews were conducted using a structured questionnaire first inquiring whether the CAN had witnessed any form of physical or verbal abuse by any of the residents. | Nursing home staff report many varied responses to RRA, a common and dangerous occurrence. CNAs seldom documented behaviors or reported them to nurses. |

| Baker/August 2016 [18] | Reduce or prevent elderly abuse not just in institutional settings, but in their homes. | More studies should be conducted and reflect on educational training. | Find measures the caregivers of elderly dementia people. | Educational training for caregivers | The purpose of the review was to assess the primary, secondary and tertiary intervention programs to reduce or prevent elderly abuse. |

| Gimm/July 2016 [19] | Estimates the prevalence and identifies risk factors of resident aggression and abuse in assisted living facilities | 6,848 older Americans in residential care facilities. | Multivariate analyses of resident-level data. | Resident-level data. | Resident aggression and abuse are a growing problem that warrants more attention from policy makers given the rising prevalence of dementia and the aging population in the United States. |

| Green/May 2016 [20] | To show that care providers have a duty to safeguard the health and wellbeing of all their residents, staff members, and care providers. | Home, nursing community, assisted living. | Defining 3 areas labeled as “boxes” in the article that explain what promoting well-being is, defining what a vulnerable adult is, and principles associated with safeguarding adults. | Implementing a quiz that checks the safeguards in place for residents. | Working together, with other agencies, groups and regulatory bodies, to ensure that policies and procedures are adequate and that those caring for the individual are fully engaged in supporting them to live free from harm, abuse, and neglect can only result in an increased level of protection and support for the individual. |

| Fang/May 2016 [21] | Highlighting the implications of using different informants, sampling strategies, and abuse subtypes in studying abuse of persons with dementia and discussing the relevant cultural consideration. | Studies and data from articles related to abuse of older persons with dementia. | A search was conducted of various databases. | Key terms were reviewed independently by each researcher. | Understanding abuse of persons with dementia, which is important for risk assessment, timely detection, prevention, and intervention of abuse. Methodological issues and their impact on study outcomes are also discussed and critiqued. Findings provide valuable information to direct future social work practice, research, and policy-making. Interdisciplinary and synergistic work from relevant fields is needed to reduce abuse and improve health and safety in persons with dementia. |

| Shilling/April 2016 [22] | Informing that elderly can also be victims of financial abuse and medical identity abuse and what consumers can do to combat this problem. | Victims are the elderly from identity theft. | Fidelity Investments and Consumer Financial Protection Bureau data. | Reported cases. | Elders can also be victims of financial abuse. Nursing facilities should be aware of medical identity theft. |

| Simone/January 2016 [23] | To identify types of elder abuse and to investigate its associated risk factors. | People 60 years or older who had contacted the Independent Complaints Authority for Old Age in the Canton of Zurich, Switzerland. | Retrospective analysis of 903 dossiers created by means of data collection by phone and email. | Dossiers created by the Independent Authority for Old Age. | Importance should be placed upon the need of a multi-faceted strategy involving the facility and caregivers, but also physicians and the community and policymakers to identify and prevent elder abuse. |

| Van der Lee/November 2015 [24] | Gain insight into what determines caregiver burden and what characteristics of patient and caregiver can cause caregiver burden. | Participants from urban region in Netherlands and selected from outpatient nursing home care. Have cognitive disorder, 65 or older, and informed consent signed by caregiver. | Longitudinal study. Data collected 3 times; at baseline, at end of treatment, and at 9 months. Study conducted in a psychiatric skilled nursing home. | Sense of Competence Scale that reflects perceived ability to cope with caring for patient. Scale contains 23 items rated on a 4-point scale. Self-perception of interpersonal behavior measured by Interpersonal Checklist of 160 items rated as yes or no. Caregiver health-related quality of life measured on EuroQol. Caregiver general burden scale measured on scale from 0 (not at all) to 100 (extremely). Caregiver emotional distress measured on scale from 0 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). | Caregivers need training to help reduce caregiving burden which can contribute to elder abuse. |

| Hirst/October 2015 [25] | Defining what is known about resident-to-resident abuse and what gerontological nurses can do about the widespread problem. | Residents in long-term care facilities. | Collecting a body of research literature regarding aggression and violence between long-term care residents. | Previous research and literature. | Resident-to-resident abuse is more prevalent than staff-to-resident abuse, but it is researched much less. RRA tends to target those residents with cognitive impairment. Staff needs to be educated on RRA to facilitate recognition. Guidelines should be provided to staff when RRA occurs. Ensure accurate and complete documentation to facilitate reporting. Aggression and violence between long-term care residents has been largely overlooked by researchers. |

| Hirst/August 2015 [26] | To identify effective approaches to preventing and addressing abuse and neglect of older adults within health care settings. | 62 studies focusing on identifying, assessing, and responding to abuse and neglect of older adults. | Systematic review of literature and submittal of article citations from expert panel members. Additionally, screening of literature for inclusion and reliability. | Expert panel and guided questions to determine appropriate study selection and data sources. | “Abuse and neglect of older adults remains under-explored.” Abuse and neglect of older adults is more likely more prevalent than reported. There exists a knowledge and training deficit around the abuse and neglect of older adults. The continued culture of de-valuing older adults will continue to allow these older adults to remain highly susceptible to all forms of abuse. |

| Dempsey/March 2015 [27] | There should be improvements to enhance a person’s quality of life with dignity in an appropriate setting of palliative care. | Dementia patients in a clinical setting. | Advanced planning to the specific care of the diseases. | Training to clinical staff. | People with dementia often do not receive the palliative care as do other terminally ill patients. |

| Ferrah/January 2015 [28] | To examine the published research on the frequency, nature, contributing factors, and outcomes of RRA in nursing homes. | Studies and data from articles related to older adults. | This review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. | Key terms were reviewed independently by each researcher. | RRA is ubiquitous with serious consequences for residents. Although physical injuries were rarely reported, each study described the negative social and psychological effects of RRA. |

| Halphen/August 2014 [29] | To show that neglect can be self-inflected in addition to others who are non-strangers. | Domestic/out-patient clinic. | Interview by APS. | Mental exam and physical exam. | In the rushed clinical environment, it is easy to miss the patient who desperately needs help. It often takes help from reliable third parties, such as APS, to gather the information needed to fully appreciate the challenges faced by elderly patients. |

| Burnett/August 2014 [30] | Healthcare professionals should report elderly abuse. | Elderly people with dementia in a clinical, residential, or home setting. | Reporting standards and clinical screenings. | Investigate. More training. | Abuse, sexual abuse, financial exploitation, caregiver neglect, psychological emotional abuse, abandonment and self-neglect. According to the article, about 80% of real elder abuse cases go unreported. |

| Tronetti/August 2014 [31] | Becoming aware of different types of elder abuse and recognizing the different stages of dementia that also affects types and level of abuse. | Previous studies; interviews of caregivers and the abuse victims. | Clinicians speak with patients in a safe, comfortable, and private setting. Patient is fed and rested but not over-sedated. | Functional Assessment Staging Tool (FAST) and the Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE). | Patients with history of partner abuse and minorities are at higher risk for abuse. Healthcare providers need training on how to recognize signs of abuse as well as risk factors. |

| Manthorpe/June 2014 [32] | To present findings from an updated investigation of secondary sources of data about the abuse of older people with dementia. Additionally, this study aimed to identify the different ways in which data on abuse of older people in hospital and care home settings are collected and collated, highlight areas where there can be confidence in the reliability of information, identify gaps in the information sources, and make recommendations to policy makers. | Various sources, including data from local authorities, government statistics, regulators, pressure groups, and reports of inquiries and reviews. | Primarily “desk research” involving an exploration of what data are collected about elder abuse, why, by whom and about what. Following “desk research”, interviews with key informants were undertaken. | Desk research and interviews. | Consistent work with local agencies should persist in order to collect appropriate data pertaining to financial abuse and other mistreatment so that policies can continue to evolve to protect the elderly. Dementia care professionals need to be educated and on high alert to the risks associated with dementia ridden residents and their exposure to abuse and neglect. |

| Epstein/April 2014 [33] | How to increase the awareness and reality that caretakers of elderly suffer from the people they are taking care of. | Home, nursing community, assisted living. | In January 2011, the National Alzheimer’s Project Act was signed into law, which led to the publication of the first National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease in May 2012. This plan proposes to develop effective treatments for Alzheimer’s by 2025, enhance care quality and efficiency, and expand supports for people affected and their caregivers. | Being a part of the family made the experience firsthand. | Attention and awareness to caregivers and care takers need to be given as well as the patients who are victim of dementia, because the caretakers suffer as well. |

| Dong/April 2014 [34] | To have all parties involved at the community, state, and federal levels. | Review the relationship between elder abuse and dementia. | Research conducted to gather information. | Lack of funds for implementing such research and training exists through federal and state programs relating to elder abuse and dementia. | There is a shortage of evidence-based intervention studies which could help victims of elderly abuse and their family members. They also identified the gaps in understanding minorities of elderly dementia people. |

| Downes/January 2013 [35] | To find risk factors for abuse and neglect, and characteristics of perpetrators. | Analyze literature on abuse of older people with dementia who are in a community dwelling. | Find strategies to prevent and manage cases of those living with dementia. | Research to provide evidence. | Find preventive measures to use that assist in elderly abuse of people with dementia. |

| Miller/October 2012 [36] | To study the effective role of the Ombudsman and ensure proper application of the Long-Term Care Ombudsman Program to improve nursing home quality of life and quality of care. | Residents, resident families, administration, staff, and advocates in a nursing home environment. | Ombudsman programs investigating complaints of abuse and neglect, and thus referring such allegations to local Adult Protective Services offices and designated state agencies. | Administration on Aging National Long-Term Care Ombudsman Program Report. | Elder abuse is a community concern, and action must be taken at local, state, and federal levels. Detection and prevention are keys to combat elder abuse. Staff must be better trained to properly recognize, and report abuse and neglect. Ombudsman and administrators should focus attention on developing and supporting resident and family councils. |

| Manthorpe/September 2012 [37] | To explore current responses of local adult safeguarding systems and consider barriers and facilitators to minimizing risks of financial abuse for people with dementia. | A purposively sampled group of 15 Adult Safeguarding Coordinators in England in 2011. | Undertaking of qualitative interviews and a framework analysis delineating themes in the transcripts. | Interviews and review of transcripts. | Healthcare professionals need to be more aware of the potential of financial abuse in patients with dementia, including the new risks associated with electronic crime. Monitoring of people with dementia needs to be sustained. |

| Sharpp/April 2012 [38] | To understand how to prevent abuse and what type of training would benefit the caregivers in preventing of the abuse. | The setting was one large unit (>30 beds) that provided care to residents with dementia in a for-profit ALF in the Western United States. | Ethnographic study used participant observation and interviews to obtain data. Data was collected and analyzed over a period of 6 months. |

The residents’ functional and mental status was assessed using Katz Basic Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Scale and the Mental Status Questionnaire (MSQ). | Four major themes emerged from the data: (a) Caregivers Level of Knowledge of Dementia, (b) Caregivers’ Lack of Knowledge in Preventing or Assessing Acute Illnesses, (c) Limitations in Monitoring and Reporting Resident Changes, and (d) Inappropriate Medication Administration. |

| Morgan/January 2012 [39] | Preventing combative behaviors in aggressive residents. | Eleven rural nursing homes located in a mid-Western Canadian province. | A prospective event-reporting log that details incidents of combative behaviors and focus groups to further explore CNAs’ perceptions of events following analysis of the diary data. | Prospective structured event-reporting diary to collect data on nurse aide attributions for resident behavior, as well as other constructs derived from attribution models (eg, caregiver emotions and behaviors) and circumstances of the incident. | Certified nursing aide’s opinions on certain incidents of combative behavior from residents with dementia, and the causes of this abusive behavior towards staff and patients residing in the nursing home. Staff cannot completely eliminate these types of behaviors but can only limit them. The staff must do their part and not just accept these behaviors as part of the job. The current study findings underscore the need to focus attention on the contextual and organizational level factors that increase the risk to front-line caregivers within long-term care settings. Many of these behaviors place the other residents at risk due to phenomenon of affecting the quality of care for these non-aggressive residents. |

| Schiamberg/January 2012 [40] | To investigate the prevalence and risk factors of staff physical abuse among elderly individuals receiving nursing home care. | A random sample of 452 adults with elderly relatives, older than 65 years, and in nursing home care in Michigan. | An empirical study investigating a random sample and creation of a logistic regression model. | Telephone survey. | Limitations in ADLs, older adult behavioral difficulties, and previous victimization are leading factors to a greater likelihood of physical abuse. Emotional closeness points to the importance of family members overseeing nursing care of older adults. |

| Peri/January 2012 [41] | Exploration of the relationship between individuals and violence as being the product of multiple levels that influence the abuse of elders. | Elder Abuse and Neglect Prevention (EANP) participants who were now in safe situations. | Qualitative methods were used to capture data about elder abuse and neglect from a range of stakeholders. Face-to-face interviews focus group interviews and telephone interviews. | Ecological framework and the ecological model. | Research has highlighted a need for more concerted efforts to help individuals and families to prepare for positive ageing. |

Assessment Tools

The 30 articles included in the qualitative analysis are summarized in Table 3, listed in order of publication, with the most recent articles located at the top. The authors re-examined the 30 articles and documented each quality improvement initiative or factor related to abuse of persons with dementia or Alzheimer’s in the long-term care setting and were sorted into 5 positive facilitators and 6 negative barriers. Similar themes were combined into one theme for consistency. The 30 articles yielded 59 instances of facilitation and 34 instances of barriers, as determined by counting the number of articles, respectively.

Facilitators

Five facilitator themes were identified, and their occurrence, frequency sum, and percent frequency are shown in Table 1. The theme most often mentioned was policies/programs; identified in 24/64 of total occurrences (41%).13,14,17,20–23,26,28,29,32,34,36,38,41 Policies/programs refer to the implementation of any new type of company policy or any program initiated within the facility or by local or federal means intended to enable the ability to reduce abuse of residents with either dementia or Alzheimer’s.13,20,26,36 Administrators should have an open-door policy to allow residents and family members to discuss issues freely, including any potential abuse by staff members.13 Leadership can work with the local ombudsman to create effective resident and family councils, as required by regulations.36 Leadership should create a culture of accountability and promote compliance with policies and procedures, including proper training and educational programs.20,26,34 Local and federal agency involvement is also needed to combat the abuse of residents through new regulations and changes to current laws, including increasing awareness of elder abuse.14,23,32 Other federal involvement could include funding of programs like the Elder Justice Act and promoting resident-centered care and culture change.26,36 Staff should be willing and able to intervene between abusive residents by talking to them calmly to diffuse the situation.17 Creating an avenue for health care providers and residents alike to report suspected abuse is another key factor in helping to reduce the incidence of abuse, in addition to the attention of leadership to take the information seriously and investigate alleged incidents immediately.22,26,29 It is of utmost importance to ensure the details of the situation are conveyed quickly and accurately.28

Table 1.

Facilitating Themes Associated With Detection And Reduction Of Abuse Of Alzheimer’s And Dementia-Ridden Residents In The Long-Term Environment

| Facilitators | Occurrences (By Article Number) | Sum | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policies/programs | 13*14,17,20,21,22*23,26,28,29*32,34,36*38,41 | 24 | 40.67% |

| Education | 16*17,21,31*32,36,37,38,40 | 14 | 23.72% |

| Working conditions | 12,13,15,16*20,26,32,39 | 11 | 18.64% |

| Screening/assessment | 12*26*36 | 8 | 13.55% |

| Staff characteristics | 35,41 | 2 | 3.38% |

Notes: *Signifies that multiple occurrences of the facilitator were located in the specific article.

A second facilitator was education, which was mentioned in 14/64 occurrences (24%).16,17,21,31,32,36–38,40 Continuing education and/or targeted training will sensitize the less-experienced and less-qualified personnel to the nuances of health issues that afflict their residents.16 Education on geriatric care and the aging process through specialized seminars or workshops and heightening staff awareness of environmental influences on behavior provides a setting for high quality of care for those with dementia and/or Alzheimer's.16,17 Educational programs focusing on cognitively impaired elders’ vulnerability to abuse should be implemented to bring public attention to the issue and reduce the social stigma of reporting.16,17 Further training should be incorporated on how to detect and respond to elder abuse and the risk factors for elder abuse in the curriculum of medical, health, social, and legal professionals.21,31,36,40 Proper documentation of incidents should be completed expeditiously with the assurance that proper quotes are utilized for accuracy.16,31 Prevention can stem from the education of health professionals around the importance of recognizing abuse and neglect and its risk factors. Facilities should provide staff training so that they are equipped to understand and react appropriately to residents’ problem behaviors.26 Training appropriate for typical nursing care is also needed. Education surrounding medication administration will limit the amount of chemical abuse and polypharmacy, whether intentional or not.16 Healthcare professionals may need to be more alert to the signs and risks of financial abuse in patients with dementia both at early and at later stages.37 Gerontological nurses can serve as role models, demonstrating proper methods of care.38

A third facilitator, working conditions, was mentioned in 11/64 occurrences (19%).12,13,15,16,20,26,32,39 Providing a great work environment leads to happy employees who care for their residents.13,16 When a long-term care facility is staffed appropriately, the employees feel well-equipped to care for the dementia and/or Alzheimer’s residents without an extreme burden of care.12 When staffing levels are appropriate, and leadership promotes and recognizes quality care, employees are more prone and motivated to the following protocol and making proper decisions in order to provide better care provisions.15,16,33 In addition to having the proper staffing levels, leadership needs to ensure that a culture of proper reporting and documentation is encouraged.13,16 In order to prevent additional instances of abuse, staff must report and document immediately.20,26 Creating an appropriate documentation process so that staff members can supply the details and get back to work will also help foster the proper following of policies and procedures.13,16 Lastly, providing an environment for employees to work together and discuss successes will help in the development of the staff and give on-the-job training opportunities.16,20,26 Addressing the organizational-level risk factors will support both resident-centered care and improved work-life.39

Screening/assessment was mentioned in 8/64 occurrences (14%).12,26,36 Initial screening of the resident is dramatically important.12 This sets the tone regarding the care plan of that resident and what is best for them.26 Assessing for diagnosis and symptoms of Alzheimer’s and/or dementia will help align the plan of care, but the facility must also assess for any prior abuse and neglect.36 Creating a high-performing assessment team will help in this area, but the resident must continually be assessed as they may choose to not share any information or may be unable to do so.12,26 As such, direct questioning to obtain the proper answer from the resident needs to be practiced as best as possible, or utilizing family or outside resources input where necessary.12,26

Staff characteristics were mentioned in 2/64 occurrences (3%).35,41 More specifically, it is very important to know the staff who are caring for those residents with Alzheimer’s or dementia.35 Staffing should not be taken lightly as it is important for that staff to have a positive attitude towards the aging population and to be mentally stable themselves before caring for this group of residents because of the prevalence of abuse.35,41

Barriers

Six barrier themes were identified about the prevention of elder abuse in residents with dementia and/or Alzheimer’s disease (Table 2). The theme most often mentioned was poor training; identified in 12/36 total occurrences (35%).13,17,18,24–27,29,30,34,38 There is a seeming lack of staff training, especially in the area of dealing with aggressive residents and those residents with dementia and/or Alzheimer’s and how to monitor and improve their quality of care.13,17,26,30,34 This lack of training regarding abuse has facilitated the inability to recognize when abuse actually occurs, what to do about the abuse, and how to properly care for those residents with end-of-life disorders.25,27 Staff continue to demonstrate little clinical understanding of dementia and how it affects the resident.38 Targeted training appears to be inadequate as there is no direct correlation between the training and the improvement of relevant knowledge of the caregiver.18 Even with proper training, caregivers are still reluctant to report suspicious behavior for fear of being reprimanded.29 A lack of training leads to staff who feel ill-prepared to provide proper care for residents.25,26 This leads to a higher level of burden on the staff, which then allows for a potential inability to provide high-quality care.24,26 When we see low-quality care being provided, we see increased numbers of residents who are more likely to be abused and neglected, especially those with dementia.24

Table 2.

Barrier Themes Associated With Detection And Reduction Of Abuse Of Alzheimer’s And Dementia-Ridden Residents In The Long-Term Environment

| Barriers | Occurrences (By Article Number) | Sum | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor training | 13,17,18,24,25,26,27,29,30,34,38* | 12 | 35.29% |

| Lack of research | 18,19,24,34*35* | 7 | 20.59% |

| Working conditions | 13,28,35,39* | 5 | 14.71% |

| Policies/programs | 25*30,34,39 | 5 | 14.71% |

| Screening/assessment | 25,30,35 | 3 | 8.82% |

| Staff characteristics | 16,26 | 2 | 5.88% |

| 34 |

Notes: *Signifies that multiple occurrences of the barrier were located in the specific article

Lack of research was mentioned in 7/36 occurrences (21%).18,19,24,34,35 Vast gaps remain in the amount of knowledge of the relationship between elder abuse and dementia.34 Research on the relationship between resident abuse and dementia tends to cover psychological and physical abuse, but not neglect or exploitation.24 Research should focus on the progression between abuse and dementia over time.19,35 Additional research is needed to resolve the uncertainties regarding the effectiveness of different interventions that have already been put in place.18

A third barrier, working conditions, was mentioned in 5/36 occurrences (15%).13,28,35,39 When staffing numbers are low, there is a higher risk of either resident-to-resident abuse or caregiver-to-resident abuse.13,28,35,39 Without having the proper number of employees, residents are not monitored effectively and have more latitude to act within their environments unmonitored.13,39 Many elderly with dementia or Alzheimer’s exhibit and increase in behaviors when they are not provided with enough personal space, or there has been an invasion of space.28,35 We see this as especially true in cases of resident-to-resident abuse.28 Undue stress on the caregiver on a day-to-day basis may also contribute to elder abuse.35 The stress and burden of caring for an individual with dementia or Alzheimer’s can be increasingly difficult over time. Mundane daily tasks are often what tend to increase the stress of the caregiver.35

Policies/programs were mentioned in 5/36 occurrences (15%).25,30,34,39 Funding issues (lack of) have caused it to be difficult for local authorities to involve themselves in helping to resolve abuse issues (outside investigating them) and for the facility to be able to implement more appropriate policies.34 Facilities often lack proper protocols or guidelines in how to deal with elder abuse as it happens and how to properly document the incident to find a resolution and prevent the abuse from occurring in the future, despite this being a federal requirement.25,39 LTC settings may have protocols for dealing with abuse, but often will not have uniform standards for their implementation, leaving the staff confused and unwilling to complete the proper paperwork and intervention.30

Furthermore, screening/assessment was mentioned in 3/36 occurrences (9%).25,30,35 A lack of screening, whether because of the lack of tools or simply because the screening was unplanned, can foster negative actions/feelings towards residents and a less than appropriate screening to be ultimately performed.30,35 We also see environmental-type triggers that may push one resident or staff member to actually commit abuse in some instances. It is necessary to determine these negative triggers and remove them from the environment.25

Just the same as the facilitators to success, staff characteristics were mentioned in 2/36 occurrences for barriers as well (6%).16,26 If the staff does not value the resident as a human being either because of their age or their condition, or the staff portrays poor social behaviors, these may lead to a higher risk of abuse to the resident.16,26

Discussion

The purpose of the review was to assess the primary, secondary, and tertiary intervention programs to reduce or prevent abuse in the long-term care setting.18 Abuse can exist in many ways such as sexual abuse, financial exploitation, caregiver neglect, psychological abuse, emotional abuse, and abandonment and self-neglect.30 Because residents can be affected by different kinds of abuse, it is important for healthcare professionals to recognize the signs.22,31 Furthermore, data collected on abuse of persons with dementia show the importance of evaluating risk assessment, timely detection, prevention, and intervention of abuse.21

It should be noted that RRA (resident-to-resident aggression) is more prevalent than staff-to-resident abuse, but it is researched much less.25 Furthermore, abuse and neglect of older adults as a whole remain under-explored.26 Detection and prevention are keys to combat elder abuse.36 As detection and prevention are current issues for continued abuse, another problem is that about 80% of elder abuse cases go unreported.26,30 There is a shortage of evidence-based intervention studies which could help victims of abuse and their family members.34 Consequently, elder abuse is a community concern, and action must be taken at local, state, and federal levels.36 Importance should be placed upon the need for a multi-faceted strategy involving the facility and caregivers, but also physicians and the community and policymakers to identify and prevent elder abuse.23

Limitations in activities of daily living (ADLs), older adult behavioral difficulties, and previous victimization are leading factors to a greater likelihood of physical abuse.40 Also, newly admitted residents (less than three months at facility) and those residents with cognitive impairment are more prone to involvement in abuse, neglect, and RRA.14,25 RRA is ubiquitous with serious consequences for residents.28 Although physical injuries were rarely reported, some of the data described the negative social and psychological effects of RRA.28 Some other high-risk factors for elderly abuse are those who have a history of partner abuse and those residents who are minorities.16

The best way to prevent abuse is to continually look for signs of abuse and attentively listening to the residents, especially those who are most vulnerable living with dementia and/or Alzheimer’s disease.13 Nursing staff and leadership must continue to monitor for abuse in the facility and not just assume they are immune to the occurrence of resident abuse.13 However, in the rushed clinical environment, it is easy to miss the patient who desperately needs help.29 It often takes help from reliable third parties, such as Adult Protective Services, to gather the information needed to fully appreciate the challenges faced by elderly patients.29 By creating a culture in which staff report all suspected adverse events and near misses, including suspicions of resident abuse, organizations can increase their chances of identifying and rectifying abusive behavior quickly.13

When informed, the physician can determine whether a treatable medical problem is causing resident behaviors.17 They can provide adequate support to the facility staff, synthesize information from different multi-disciplinary team members, keep the family informed, and set realistic expectations for treatment. Physician and nursing assessment may also uncover other symptoms that may be contributing to this abusive behavior, such as inadequately treated pain, delirium, constipation, or infection, all of which are common and difficult to assess among cognitively impaired nursing facility residents.17 Nursing facility physicians play an important role in controlling this type of abuse.17

Four major areas emerged from the data: (a) caregivers’ level of knowledge of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, (b) caregivers’ lack of knowledge in preventing or assessing acute illnesses, (c) limitations in monitoring and reporting resident changes, and (d) inappropriate medication administration.38 The most notable fact is the limited education of the staff and inadequate training of the floor nurses and certified nursing assistants (CNAs).38 Overall, we see a knowledge and training deficit surrounding the abuse and neglect of older adults.26 Caregivers are often unable to demonstrate a clinical understanding of dementia and how it affects older adults.38 This finding is consistent with previous studies that found employees in long-term care facilities lacked adequate knowledge of dementia and did not have adequate knowledge or skills to provide quality care.38

Thorough evaluations from staff members, especially physicians, are a necessity to determine a proper plan of care.25 Documenting carefully, noting all changes in the resident, and being especially attentive to inconsistencies between an injury and the causal story, will provide the baseline for necessary modifications in care.25 It will take a group effort by all medical staff at the long-term care facility to notice and prevent abuse of the resident.25

Due to gaps in understanding the care of dementia residents, many residents are not receiving palliative care as do other terminally ill patients.27 Facilities need to offer training and have better screening processes for employees to recognize resident issues, and not rely solely on just asking the resident.12,24 The facility must diligently hire staff who are fit to care for older adults and train staff to recognize and report suspected abuse.13,36 Dementia care professionals need to be educated and on high alert to the risks associated with dementia-ridden residents and their exposure to abuse and neglect.32 Staff must be educated, but leadership involvement is the most important factor in implementing any programs promoting staff awareness and resident-centered care.15 Healthcare professionals cannot expect residents to always be forthcoming with information for fear of possible retaliation from their caregiver.16 Being aware of the different risk factors will help healthcare professionals be more mindful of their residents’ needs, as well as signs of abuse.16 Additionally, healthcare professionals need to be more aware of the potential of financial abuse in patients with dementia, including the new risks associated with electronic crime.37

Ombudsmen and leadership should focus attention on developing and supporting resident and family councils, as emotional closeness points to the importance of family members overseeing nursing care of older adults.36,40 Research has highlighted a need for a more concerted effort to assist individuals and families to prepare for positive aging.41 Consistent work with local agencies should persist in order to collect appropriate data pertaining to financial abuse and other mistreatment so that policies can continue to evolve to protect the resident.32 Furthermore, working together with other agencies, groups, and regulatory bodies to ensure that policies and procedures are adequate and that those caring for the individual are fully engaged in supporting them to live free from harm, abuse, and neglect can only result in an increased level of protection and support for the individual.20

It is also very important to provide attention and awareness to caregivers, in addition to the residents who are victims of dementia and/or Alzheimer’s disease, because the caregivers also suffer due to boredom, lack of interest, physical pain administered by the resident, and apathy of residents or families.33 Nursing facility staff report many varied responses regarding RRA, a common and dangerous occurrence.17 Additionally, CNAs seldom document behaviors or report incidents to nurses for fear of backlash.17 Overall, staff cannot completely eliminate these types of behaviors or abuse, but can limit them. The staff and leadership must do their part and not just accept these behaviors as part of the job. Often, CNAs do not report these incidents to the appropriate staff member.39

Conclusion

As determined, there is an increasing rate of abuse in the long-term care setting, specifically for those individuals with either dementia or Alzheimer’s. Common causes and risk factors leading to this abuse include poor training, negative working conditions, poor screening for prior abuse of dementia or Alzheimer’s symptoms, and the apathy or bad attitudes of staff. Additional research needs to be conducted to determine more appropriate programs to implement in order to prevent abuse and neglect. Some attributes to combating abuse of this population are proper education, positive working conditions, and good screening/assessment practices. Facilities should ensure that the culture of the long-term care environment is to provide great quality care, which involves continuous monitoring by leadership and nursing staff to ensure the residents’ living arrangements are safe but modified when necessary. Safety should involve everyone, including physicians and the community, by creating educational tools regarding the risks associated with dementia and exposure to abuse and neglect. Reporting requirements should be a priority for those with behavioral problems, medication issues, or those who were previously victimized. Lastly, residents with dementia and/or Alzheimer’s should be cared for by those who have special training who can recognize the abuse and assist the person as needed.

Disclosure

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest with respect to research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. No author received financial support for research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.National Center on Elder Abuse. Abuse of residents of long-term care facilities. 2012. Available from: https://ncea.acl.gov/NCEA/media/Publication/ResearchBriefLTCF.pdf Accessed October08, 2019.

- 2.National Center on Elder Abuse. The national elder abuse incidence study: final report 1-1. Available from: https://www.acl.gov/sites/default/files/programs/2016-09/AbuseReport_Full.pdf Accessed September 1998.

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services. Admission, transfer, and discharge rights. Retrieved from https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/CFR-2011-title42-vol5/CFR-2011-title42-vol5-sec483-12 Accessed October08, 2019.

- 4.Pitman A, Metzger KE. Nursing home abuse and neglect and the Nursing Home Reform Act: an overview. NAELA J. 2018;14:137–154. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yon Y, Ramiro-Gonzalez M, Mikton CR, Huber M, Sethi D. The prevalence of elder abuse in institutional settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Public Health. 2018;29(1):58–67. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cky093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braaten KL, Malmedal W. Preventing physical abuse of nursing home residents- as seen from the nursing staff’s perspective. Nurs Open. 2017;4(4):274–281. doi: 10.1002/nop2.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Natan MB, Lowenstein A. Feature. Study of factors that affect abuse of older people in nursing homes … includes discussion. Nurs Manag. 2010;17(8). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jogerst G, Daly J, Hartz A. Ombudsman program characteristics related to nursing home abuse reporting. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2005;46(1):85–98. doi: 10.1300/J083v46n01pass:[_]06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mileski M, Kruse CS, Brooks M, Haynes C, Collingwood Y, Rodriguez R. Factors concerning veterans with dementia, their caregivers, and coordination of care: A systematic literature review. Mil Med. 2017;182(11–12):e1904–e1911. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mileski M, Topinka JB, Brooks M, Lonidier C, Linker K, Vander Veen K. Sensory and memory stimulation as a means to care for individuals with dementia in long-term care facilities. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:967. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S153113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Famakinwa A, Fabiny A. Assessing and managing caregiver stress: development of a teaching tool for medical residents. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2008;29(1):52–65. doi: 10.1080/02701960802074289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young M (2018). Stay alert to signs of elder abuse: think of falls, residence violence. Relias. Retrieved from https://www.reliasmedia.com/articles/143140-stay-alert-to-signs-of-elder-abuse-think-of-falls-resident-violence Accessed October08, 2019.

- 13.Rose VL. Preventing abuse, neglect, and exploitation of residents in nursing homes. Ann Long-Term Care. 2018;26(3):11–13. doi: 10.25270/altc.2018.06.00034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caspi E. The circumstances surrounding the death of 105 elders as a result of resident-to-resident incidents in dementia in long-term care homes. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2018;30(4):284–308. doi: 10.1080/08946566.2018.1474515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobsen FF, Mekki TE, Førland O, et al. A mixed method study of an education intervention to reduce use of restraint and implement person-centered dementia care in nursing homes. BMC Nurs. 2017;16(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s12912-017-0263-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wangmo T, Nordstrom K, Kressig RW. Preventing elder abuse and neglect in geriatric institutions: solutions from nursing care providers. Geriatr Nurs. 2017;38:385–392. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosen T, Lachs MS, Teresi J, Eimicke J, Haitsma KV, Pillemer K. Staff-reported strategies for prevention and management of resident-to-resident elder mistreatment in long-term care facilities. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2015;28(1):1–13. doi: 10.1080/08946566.2015.1029659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baker PR, Francis DP, Hairi NN, Othman S, Choo WY. Interventions for preventing abuse in the elderly. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gimm G, Chowdhury S, Castle N. Resident aggression and abuse in assisted living. J Appl Gerontol. 2018;37(8):947–964. doi: 10.1177/0733464816661947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green D. Safeguarding and protection of vulnerable adults. Nurs Res Care. 2015;17(5):293–296. doi: 10.12968/nrec.2015.17.5.293 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fang B, Yan E. Abuse of older persons with dementia: a review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2018;19(2):127–147. doi: 10.1177/1524838016650185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shilling D. New trends in financial abuse and identity theft. Family & Intimate Partner Violence Q. 2016;8(4). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simone L, Wettstein A, Senn O, Rosemann T, Hasler S. Types of abuse and risk factors associated with elder abuse. Swiss Med Wkly. 2016;146(0304). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Lee J, Bakker TJ, Duivenvoorden HJ, Dröes RM. Do determinants of burden and emotional distress in dementia caregivers change over time? Aging Ment Health. 2017;21(3):232–240. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1102196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirst SP. Resident-to-resident abuse. J Gerontol Nurs. 2015;41(12):3–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirst SP, Penney T, McNeill S, Boscart VM, Podnieks E, Sinha SK. Best-practice guideline on the prevention of abuse and neglect of older adults. Can J Aging. 2016;35(2):242–260. doi: 10.1017/S0714980816000209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dempsey L, Dowling M, Larkin P, Murphy K. The unmet palliative care needs of those dying with dementia. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2015;21(3):126–133. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2015.21.3.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrah N, Murphy BJ, Ibrahim JE, et al. Resident-to-resident physical aggression leading to injury in nursing homes: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2015;44(3):356–364. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halphen JM, Burnett J. Elder abuse and neglect: appearances can be deceptive. Psychiatr Times. 2014;31(8):14–15. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burnett J, Achenbaum WA, Murphy KP. Prevention and early identification of elder abuse. Clin Geriatr Med. 2014;30(4):743–759. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2014.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tronetti P. Evaluating abuse in the patient with dementia. Clin Geriatr Med. 2014;30(4):825–838. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2014.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manthorpe J. The abuse, neglect and mistreatment of older people with dementia in care homes and hospitals in England: the potential for secondary data analysis: innovative practice. Dementia. 2015;14(2):273–279. doi: 10.1177/1471301214541177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Epstein-Lubow G. A family disease: witnessing firsthand the toll that dementia takes on caregivers. Health Aff. 2014;33(4):708–711. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dong X, Chen R, Simon MA. Elder abuse and dementia: a review of the research and health policy. Health Aff. 2014;33(4):642–649. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Downes C, Fealy G, Phelan A, Donnelly N, Lafferty A. Abuse of Older People with Dementia: A Review. National Centre for the Protection of Older People; 2013;1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller M. Ombudsmen on the front line: improving quality of care and preventing abuse in nursing homes. Generations. 2012;36(3):60–63. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manthorpe J, Samsi K, Rapaport J. Responding to the financial abuse of people with dementia: a qualitative study of safeguarding experiences in England. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(9):1454–1464. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212000348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharpp TJ, Kayser-Jones JS, Young HM. Care for residents with dementia in an assisted living facility. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2012;5(3):152–162. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20120410-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morgan DG, Cammer A, Stewart NJ, et al. Nursing aide reports of combative behavior by residents with dementia: results from a detailed prospective incident diary. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(3):220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schiamberg LB, Oehmke J, Zhang Z, et al. Physical abuse of older adults in nursing homes: a random sample survey of adults with an elderly family member in a nursing home. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2012;24(1):65–83. doi: 10.1080/08946566.2011.608056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peri K, Fanslow J, Hand J, Parsons J. Keeping older people safe by preventing elder abuse and neglect. Soc Policy J N Z. 2012;35:159–173. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- National Center on Elder Abuse. Abuse of residents of long-term care facilities. 2012. Available from: https://ncea.acl.gov/NCEA/media/Publication/ResearchBriefLTCF.pdf Accessed October08, 2019.