Abstract

We describe the synthesis and fluorescence spectral characterization of a pH-sensitive metal–ligand complex, [Ru(deabpy)(bpy)2]2+, where deabpy is 4,4′-di-ethylaminomethyl-2,2′-bipyridine. This metal-ligand complex (MLC) was found to display pH-dependent intensities, emission spectra, and decay times, with the changes centered near the physiological useful pH value of 7.5. The apparent pKa values were not found to be dependent on ionic strength. The compound was found to be useful for lifetime-based sensing by phase-modulation fluorometry. Global analysis of the intensity decays over a range of pH values revealed two decay times of 235 and 380 ns, associated with the protonated and unprotonated forms, respectively. Because of its long decay time, optical pH measurements could be accomplished by phase-modulation fluorometry with a conveniently low modulation frequency of 700 kHz. The lifetime data were obtained with either a amplitude-modulated laser or with an amplitude-modulated blue-light-emitting diode. This pH-sensitive complex also displays a modest spectral shift with change in pH, allowing its use as a wavelength-ratiometric MLC probe. One can imagine lifetime sensors for a variety of blood cations and point-of-care assays based on long-lifetime metal-ligand complexes and simple solid-state light sources and detectors.

Optical methods for measurement of blood chemistry are of great interest because they offer the possibility of decreased cost and less handling of possibly contaminated blood. Among the various optical methods, fluorescence detection seems to offer the advantages of high sensitivity and ion-selective fluorescence probes. The current status of fluorescence sensing has described in recent literature (1–6).

During the past several years there has been increasing interest in lifetime-based sensing (7–9). In this method the analyte concentration is determined from the decay time of the fluorophore and its dependence on the analyte of interest. Lifetime-based sensing can be preferred over intensity-based methods because the lifetime is mostly independent of the probe concentration and can be unaffected by photobleaching or wash-out of the probe. The possible mechanisms of lifetime-based sensing have been reviewed (7). Lifetimes have been measured through skin (10) and in turbid media (11), suggesting the possibility of transdermal sensing with long-wavelength light sources. Lifetime sensors have now been identified from a large number of analytes, including pH (12, 13), NH3 (14), CO2 (15), Ca2+ (16), Mg2+ (17), Cu2+ (18), immunoassays (19), and glucose (20). Practical lifetime-based sensing applications have also been described for pO2 and pCO2 in bioprocess (21–23).

At present most lifetime-based fluorophores display lifetimes from 1 to 10 ns (7), which requires relatively fast electronics for time–domain lifetime measurements or modulation frequencies from 10 to 100 MHz for frequency–domain measurements. Additionally, the autofluorescence from most biological specimens displays decay times near 1–10 ns, making it difficult to separate the desired signal from the interfering autofluorescence. The availability of longer-lived probes would allow one to design simple instruments for point-of-care assays and off-gating the short lived autofluorescence in circumstances which require high-sensitivity detection. In fact, a solid-state phase-modulation fluorometer has already been reported (24). One can also imagine the use of long-lifetime metal–ligand probes in fluorescence microscopy for high-sensitivity in situ hybridization (25) as for chemical imaging by lifetime imaging (26–28).

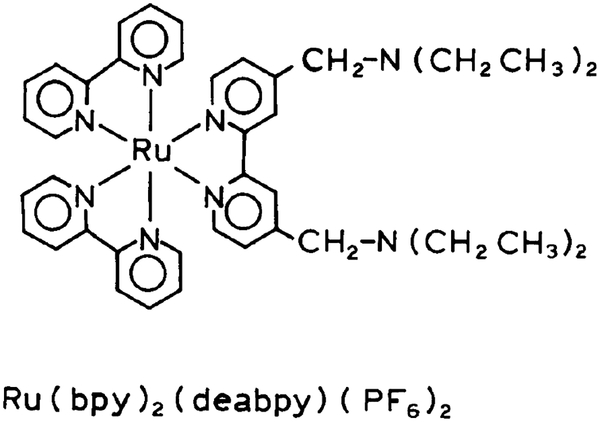

We now describe the synthesis and spectral properties of a long-lived metal–ligand complex (MLC)2 which displays pH-sensitive emission in the physiological range from 6 to 8. This compound [Ru(deabpy)(bpy)2]2+ (Scheme I) was found to display pH-sensitive intensities, phase angles, and modulations with an apparent pKa near 7.5. This pH-dependent MLC can be regarded of the first of a series of cation-sensitive probes which display decay times in excess of 200 ns.

SCHEME I.

Structure of [Ru(deabpy)(bpy)2]2+. MLC pH sensor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis of [Ru(deabpy)(bpy)2](PF6)2

The synthetic procedure for preparation of [Ru(deabpy)(bpy)2](PF6)2 followed published procedures (29–30) with slight modification. The (CH2Br)2bpy was prepared by following reported methods (30, 31), and the resulting compound was purified by column chromatography (30). The ligand 4,4′-diethylaminomethyl-2, 2′-bipyridine (deabpy) was prepared by refluxing (CH3CH2)2NH with (CH2Br)2bpy in CCl4 and purified by using a silica column using a acetone/dichloromethane solvent mixture. Ru(bpy)2Cl2 was stirred in acetone for about 2 hr with silver triflate, the white precipitate of silver chloride was removed, and the resulting red color solution was stirred with deabpy ligand for about 6 hr. The acetone was removed and the residue redis-solved in water, precipitated with ammonium hexaflu-orophosphate, and filtered. The brick-red solid was re-dissolved in acetonitrile and chromatographed with an acetonitrile/toluene mixture over alumina. The [Ru-(deabpy)(bpy)2](PF6)2 was characterized by proton NMR.

Instrumentation and Procedures

Chemicals and solvents were purchased from Aldrich and used without further purification. Absorption spectra were measured using a Perkin–Elmer lambda 6 UV/Vis spectrophotometer. We observed two isobestic points at 414 nm and 475 nm. The absorbance at 450 nm of different samples was measured to obtain the ground state pKa.

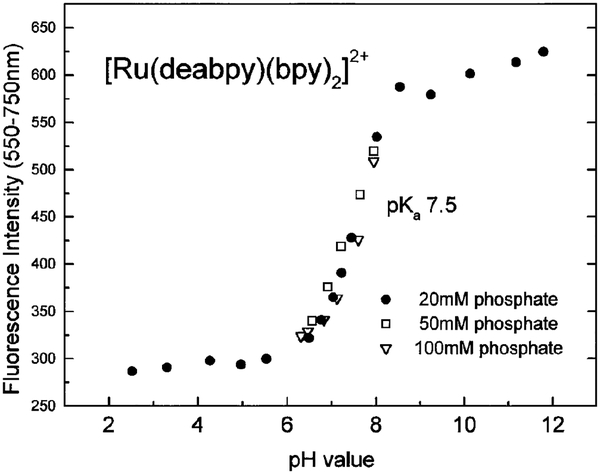

Ru(bpy)2(deabpy)(PF6)2 solutions at different pH values were prepared by dissolving equal amounts of aqueous Ru(bpy)2(deabpy)(PF6)2 in different buffer solutions. From pH 2 to pH 4.7, we used citrate buffer; from pH 4.8 to pH 6.3, we used acetate buffer; from pH 6.4 to pH 7.8, we used phosphate buffer; from pH 7.8 to pH 9.0, we used Tris buffer; from pH 9.2 to pH 11, we used carbonate/bicarbonate buffer; from pH 11 to pH 12, we used dibasic sodium phosphate/sodium hydroxide buffer. Unless stated otherwise the buffer concentrations were 20 mM and contained 0.1 M potassium chloride to maintain ionic strength. In order to determine if the pKa was dependent on the buffer concentration, we also prepared sample solutions in 50 and 100 mm phosphate and buffer with pH values between 6 and 8 and compared their total fluorescence intensity from 550 and 750 nm.

The fluorescence emission spectra were measured using Aminco Bowman Series AB2 Luminescence Spectrometer with an excitation wavelength of 414 nm. The acidic sample (at low pH) had an emission maximum at 650 nm, and the basic sample had an emission maximum at 620 nm. The emission intensity ratios (620/650 nm) of the different sample were also recorded.

For the phase/modulation measurements, an air-cooled argon ion laser (output at 488 nm) was used as the excitation light source, and the modulation frequency was set at 700 kHz. On the emission side, a long-wave-pass filter was used to collect the fluorescence with wavelengths longer than 600 nm. The reference solution used here was an aqueous solution of Texas Red with a reference lifetime of 4 ns. For the lifetime measurements, we used the same instrumentation and reference solution and 23 different modulation frequencies ranging from 11 kHz to 2 MHz.

Although not shown, phase modulation measurements were also performed with a Nichia blue LED (NLPB500; Nichia America Co., Lancaster, PA; maximum output, 450 nm) as the excitation light source. In this case, the measurements were performed on an ISS K2 Multifrequency Phase and Modulation Fluorometer (Champaign, IL). A set of Andover 500FL07, 600FL07, and 700FL07 short-wave-pass filters (Salem, NH) was added in the excitation path to ensure the cutoff of light from the LED with wavelengths longer than 500 nm. On the emission side, an Andover 600FH90 long-wave-pass filter was used to collect the fluorescence with wavelengths longer than 600 nm. An 650FH90 or 700FH90 filter was used to replace the 600FH90, where necessary. The reference solution used for the lifetime measurement was a 0.5% solution of Du Pont Ludox HS-30 colloidal silica in water, with the intensity matched to that of the sample by using neutral-density filter(s) in its emission path. All experiments were performed at an ambient temperature. In this case, single-frequency measurements were performed at 823 kHz.

Single and multiexponential intensity decays were recovered from the multifrequency data as described previously (32, 33). The data were analyzed globally in terms of the multiexponential model.

| [1] |

where Ik(t) is the intensity decay at each pH (k) value, τi is the decay time, and αik is the amplitude. For the global analysis we assumed that the αik values would depend on pH, but that the two lifetimes would be independent of pH. The goodness-of-fit was judged by the usual criterion with assumed uncertainties in phase δp = 0.2° and modulation δm = 0.005.

RESULTS

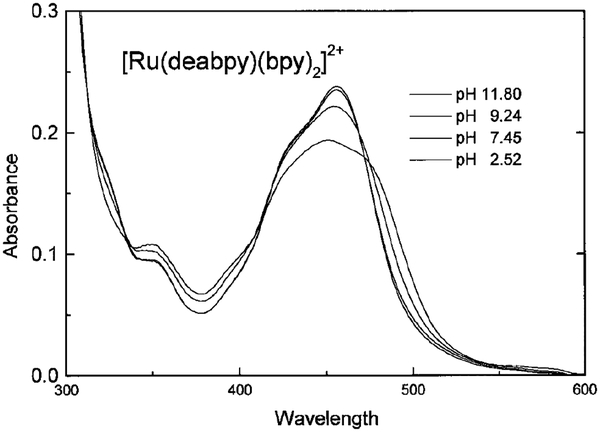

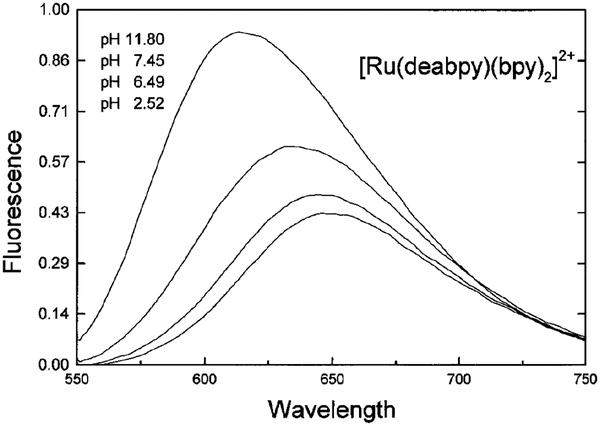

Absorption and emission spectra of [Ru(deabpy) (bpy)2]2+ at pH values from 2 to 12 are shown in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively. Only modest changes are seen in the absorption spectrum, but the emission spectrum increases about threefold as the pH increases from 2.52 to 11.8. The pH-dependent intensity changes are shown in Fig. 3, and reveal a pKa value near 7.5. This pKa value is ideally suited for measurements of blood pH, where the clinically relevant range is from 7.35 to 7.46, with a central value near 7.40. In addition, much cell culture work is performed near pH 7.0–7.2. We attribute the changes in absorption and emission to deprotonation of the amino groups on [Ru(deabpy)(bpy)2]2+ (Scheme I).

FIG. 1.

pH-dependent absorption spectra of [Ru(deabpy)(bpy)2](PF6)2.

FIG. 2.

pH-dependent emission spectra of [Ru(deabpy)(bpy)2](PF6)2. Excitation at 414 nm.

FIG. 3.

pH-dependent fluorescence intensities (557–750 nm) of [Ru(deabpy)(bpy)2](PF6)2 in different buffer concentrations.

We were pleasantly surprised by the pKa value near 7.5, as we expected a higher pKa near 9, based on the structures shown in Scheme I. In fact, we initially attempted to synthesize a different structure which contained hydroxyl groups on the terminal methyl groups. These hydroxyl groups were thought to be needed to obtain a pKa near 7.5, based on their presence in the widely used buffer Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane). However, we had difficulties synthesizing the hydroxyl-containing compound and decided to synthesize [Ru(deabpy)(bpy)2]2+ as an initial step.

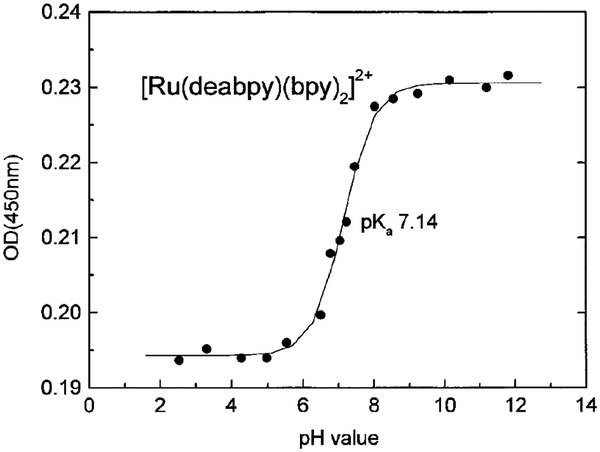

We also considered whether the pKa observed by fluorescence is in fact the ground state pKa. The ground state pKa was determined from the changes in absorption at 450 nm (Fig. 4). In this case the pKa was found to be 7.14, somewhat lower than the value of 7.5 observed by fluorescence. This small difference in pKa values is not surprising, as metal–ligand complexes with ionizable diimine ligands often display different pKas in the ground and excited states. Importantly, the difference is not large, and our probe does not seem to be sensitive to ionic strength. The same apparent pKa values were observed in 20, 50, and 100 mm phosphate buffer (Fig. 3). We will describe fluorescence changes as due to ionization events at pKa values, but we recognize that the ground state and excited state pKa values may be slightly different.

FIG. 4.

pH-dependent absorption of [Ru(deabpy)(bpy)2]2+ at 450 nm.

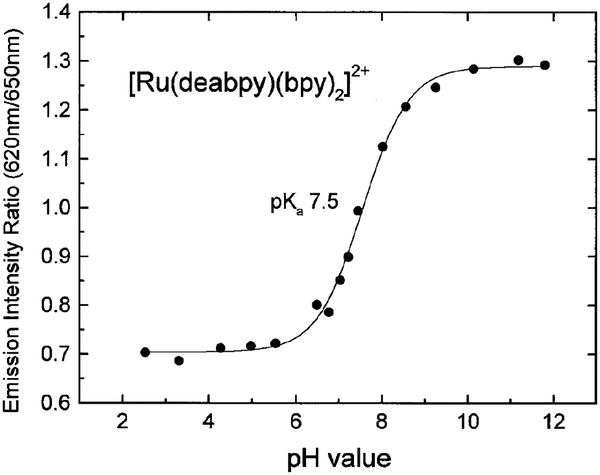

Figure 2 shows that the emission spectrum shifts to longer wavelengths as the amino groups are protonated at low pH. This suggests the use of [Ru(deabpy)(bpy)2]2+ as a wavelength-ratiometric probe. Such ratiometric probes are already in wide-spread use for measurement of Ca2+ (34, 35) and pH (36, 37), but these are not MLC probes and they display ns decay times. We used the emission spectra at various pH values to obtain a wavelength-ratiometric calibration curve (Fig. 5). To the best of our knowledge [Ru(deabpy)(bpy)2]2+ is the first MLC probe which can be used as a ratiometric probe.

FIG. 5.

Wavelength-ratiometric measurements of pH using the emission intensities at 620 and 650 nm.

The emission shift to longer wavelengths at low pH (Fig. 2) seems to be generally understandable in terms of the electronic properties of the excited MLCs. The long wavelength emission is thought to result from a metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) state in which an electron is donated from Ru to the ligand. The protonated form of deabpy is probably a better electron acceptor, lowering the energy of the MLCT state, shifting the emission to longer wavelengths, and there-by decreasing the lifetime. In previous studies we observed that the emission spectrum of [Ru(dcbpy)(bpy)2]2+, where dcbpy is 4,4′-dicarboxy-2,2′-bipyridine, displays a red shift relative to Ru(bpy)3 (38, 39). The dcbpy ligand is probably a better electron acceptor than bpy. These results suggest a general approach to designing wavelength-ratiometric MLC probes based on cation-dependent changes in the electron affinity of the ligand.

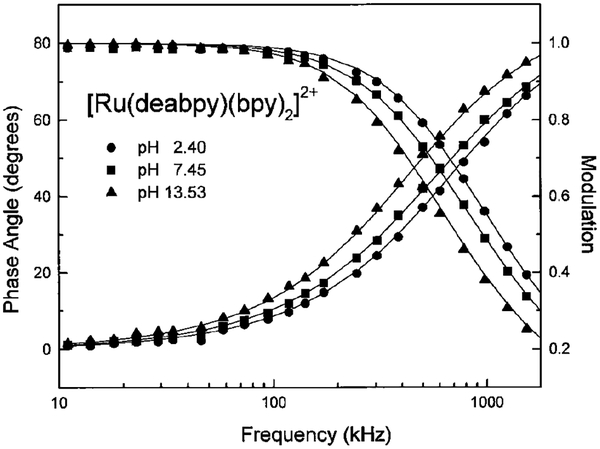

Examination of the emission spectra (Fig. 2) reveals that the probe is fluorescent in both forms, protonated and unprotonated. This suggests that it can be useful as a lifetime probe because each form is fluorescent and may display distinct decay times. Frequency-domain intensity decays of [Ru(deabpy)(bpy)2]2+ are shown in Fig. 6. At low pH with protonated amino groups the mean decay time is near 240 ns, and at high pH the mean decay time increases to near 390 ns. The intensity decay was found to be reasonably fit to a single exponential at each pH value (Table 1). The decay times were similar, and difficult to resolve at a single pH value, so that only a modest decrease in was found for the double exponential fit (Table 1). However, the apparent decay times found from the single exponential fit increases with increasing pH. Similar intensity decays were found whether the entire emission above 600 nm was observed or if one just observed the red side of the emission above 700 nm.

FIG. 6.

pH-dependent frequency-domain intensity decays of [Ru(deabpy)(bpy)2]2+ at pH 2.40 (●), 7.45 (■), and 13.53 (▲).

TABLE 1.

Single Decay Time Analysis of Ru(bpy)2(deabpy)

| pH | τ (ns) | |

|---|---|---|

| 2.40 | 236 | 5.22 (4.74)a |

| 5.89 | 252 | 3.51 (3.19) |

| 6.91 | 262 | 2.91 (1.82) |

| 7.45 | 284 | 6.24 (3.69) |

| 8.02 | 327 | 3.13 (3.18) |

| 13.5 | 392 | 2.77 — |

The values in parentheses are for the double exponential fit.

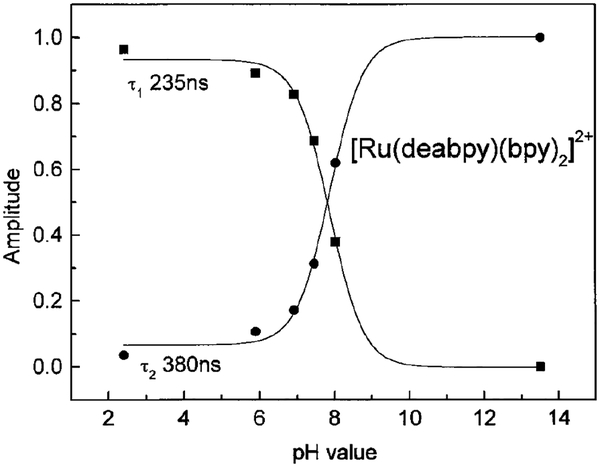

One can expect the intensity decay to be a multiexponential at intermediate pH values, where both species are present. Hence, we examined the intensity decays at several pH values between 2 and 12. Because of the closely spaced decay times it was difficult to recover the two decay times at each pH. Hence, we performed a global analysis in which the preexponential factors (αik values) were assumed to be pH dependent, and the same two decay times would be present at all pH values. For a global analysis the frequency-domain data were only poorly fit by the single lifetime model, as seen from the elevated of value (Table 2). Analysis in terms of the two lifetime models resulted in a reduced value of . The results of this global analysis are shown graphically in Fig. 7. These data show that the amplitude associated with the 235-ns decay time decreases near pH 7.5, and that the amplitude associated with the 380-ns component in-creases at this same pH value. Importantly, the two recovered decay times were comparable to those ob-served at pH 2 and 12 (Table 1), supporting the assignment of the 235-ns decay time to the protonated form and the 380-ns decay time to the unprotonated form of [Ru(deabpy)(bpy)2]2+.

TABLE 2.

Global pH-Dependent Intensity Decay Analysis of Ru(deabpy) (bpy)2

| pH | τi (ns) | τ2 (ns) | α1 | α2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.4 | 235 | 380 | 0.964 | 0.036 | |

| 5.8 | 235 | 380 | 0.893 | 0.107 | |

| 6.91 | 235 | 380 | 0.828 | 0.172 | 4.66a |

| 7.45 | 235 | 380 | 0.687 | 0.313 | |

| 8.02 | 235 | 380 | 0.380 | 0.620 | |

| 13.5 | 235 | 380 | 0 | 1.0 |

For the global single decay time analysis the value was 124, with a mean decay of 294 ns.

FIG. 7.

pH-dependent amplitude of the two decay time global analyses (Table 2).

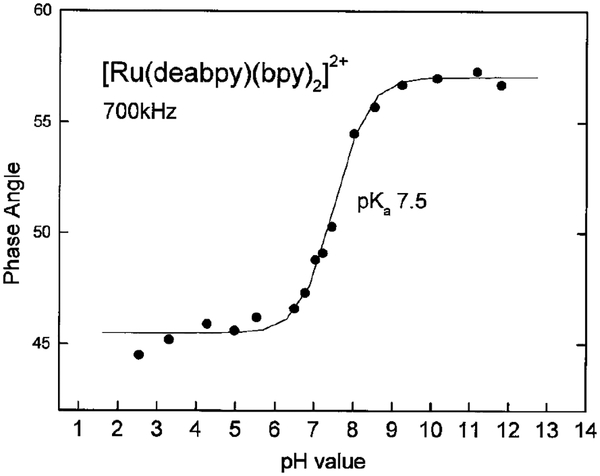

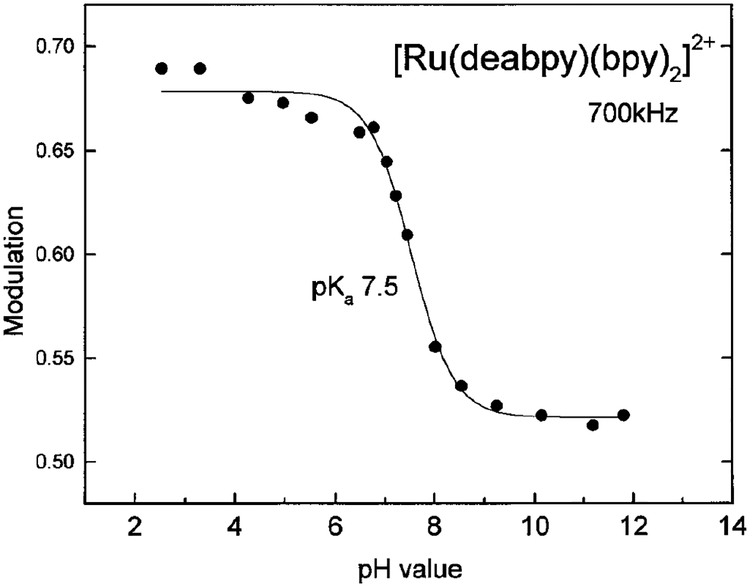

To use [Ru(deabpy)(bpy)2]2+ as a pH sensor we measured its pH-dependent phase and modulation, with a light modulation frequency of 700 kHz (Fig. 8 and 9, respectively). As the pH is increased, the phase angles increased from 45° to 57°, and the modulation decreases from 0.69 to 0.52. Although not shown, similar data were obtained using the blue LED excitation source at 823 kHz. Conveniently, these changes occur over the pH range from 6 to 8. With present instrumentation one can expect the phase angles and modulation to be accurate to 0.1° and 0.005° in modulation. Hence, the pH can be measured to about 1 part in 50, or ±0.04 from pH 6 to 8. Such resolution is acceptable by medical standards (40); however, one can expect improved phase and modulation occurring with dedicated instrumentation and/or the use of multiple light modulation frequencies. This capability should find immediate applications for noninvasive pH sensing in tissue culture vessels, analogous to that recently reported for oxygen sensing (23).

FIG. 8.

pH-dependent phase angles of [Ru(deabpy)(bpy)2]2+ with a modulation frequency of 700 kHz.

FIG. 9.

pH-dependent modulation of [Ru(deabpy)(bpy)2]2+ with a modulated frequency of 700 kHz.

DISCUSSION

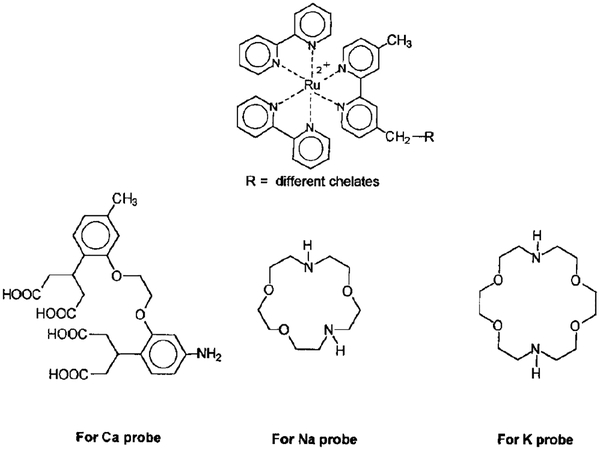

The MLC probe described in this report is sensitive to pH, but a variety of other ions are of medical interest. We believe it will be possible to create metal–ligand probes for a wide variety of analytes. For instance, it is now known that the lifetimes of ns probes with ion-chelating groups display changes in lifetime upon chelation. Such ns probes are known for Ca2+ (41), Mg2+ (17), Na2+ (42), and K+ (43). It seems probably that coupling of the appropriate chelating groups, such as BAPTA or an aza-crown ether, to a metal–ligand complex will result in metal-ligand probes which display ion-sensitive lifetimes. The structures of such potential probes are shown in Scheme II. Metal–ligand complexes have already been used in immunoassays based on polarization (39) or lifetimes modified by resonance energy transfer (44).

SCHEME II.

Possible structures of cation-sensitive metal-ligand probes. Ruthenium metal complexes for Na, K, and Ca probes.

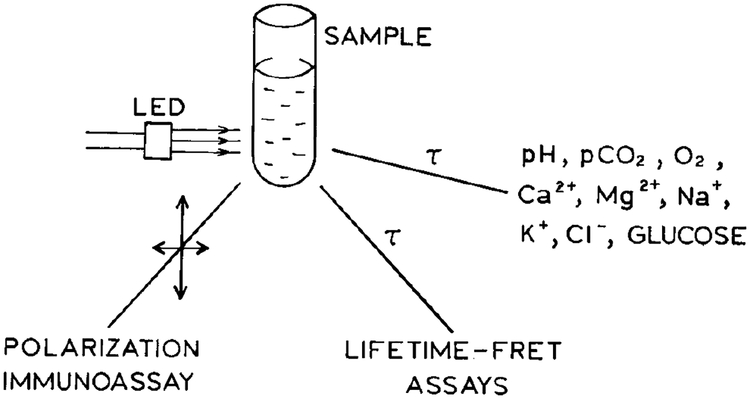

Once such long-lifetime cation probes are available one can imagine many applications with simple instrumentation. Because of the long decay time, the light modulation frequencies can be near 1 MHz or lower. Hence, the light source can be an amplitude-modulated light emitting diode (LED). The optical output of the LED is easily modulated at kHz to low MHz frequencies (45–47). If necessary, signal detection can be performed simultaneously with electronic off-gating of the detector to suppress the ns components due to autofluorescence from the samples. Such probes and simple instrumentation may allow sensing in blood serum or whole blood, as shown in Scheme III. Hence, the development of metal-ligand complexes can enable simple instrumentation for point-of-care clinical chemistry.

SCHEME III.

Point-of-care assays based on metal-ligand probes with a LED light source.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support for this research from the National Science Foundation (Grants BES-9413262 and BCS-9157852) and the National Institute of Health (Grants RR-08119 and RR-10416–01). Matching funds were provided by Genentech, Inc.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: bpy, 2,2′-bipyridine; deabpy, 4,4′-diethyl-aminomethyl-2,2′-bipyridine; LED, light-emitting diode; MLC, metal-ligand complex; MLCT, metal-ligand complex transfer; dcbpy, 4,4′-dicarboxy-2,2′-bipyridine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldini F (Ed.) (1994) Sens. Actuators B, 439. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfbeis OS (Ed.) (1992) Sens. Actuators B, 565. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lakowicz JR (Ed.) (1994) Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Vol. 4, Probe Design and Chemical Sensing, p. 501 Plenum, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slavik J (1994) Fluorescent Probes in Cellular and Molecular Biology, p. 295, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lakowicz JR (Ed.) (1995) SPIE Proc. 2388, 598. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bambot SB, Lakowicz JR, and Rao G (1995) Trends Biotechnol. 13, 106–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szmacinski H, and Lakowicz JR (1994) in Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Vol. 4, Probe Design and Chemical Sensing (Lakowicz JR, Ed.), pp. 295–334, Plenum, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lippitsch ME, and Draxler S (1993) Sens. Actuators B 11, 97–101. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lippitsch ME, and Draxler S (1996) Appl. Optics 35(21), 4117–4123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bambot SB, Rao G, Romauld M, Carter GM, Sipior J, Terpetschnig E, and Lakowicz JR (1995) Biosens. Bioelectron 10(6/7), 643–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szmacinski H, and Lakowicz JR (1995) Sens. Actuators B 30, 207–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szmacinski HS, and Lakowicz JR (1993) Anal. Chem 65, 1668–1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bambot S, Sipior J, Lakowicz JR, and Rao G (1994) Sens. Actuators B 22, 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang Q, Sipior J, Lakowicz JR, and Rao G (1995) Anal. Biochem 232, 92–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sipior J, Bambot S, Romauld M, Carter GM, Lakowicz JR, and Rao G (1995) Anal. Biochem 227, 309–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szmacinski H, and Lakowicz JR (1995) Cell Calcium 18, 64–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szmacinski H, and Lakowicz JR (1996) J. Fluoresc 6, 83–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birch DJS, Rolinski OJ, and Hatrick D (1996) Rev. Sci. Instrum 67(8), 2732–2737. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozinskas AJ, Malak H, Joshi J, Szmacinski H, Britz J, Thompson RB, Koen PA, and Lakowicz JR (1992) Anal. Biochem 213, 264–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lakowicz JR, and Maliwal BP (1993) Anal. Chim. Acta 271, 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bambot S, Holavanahali R, Lakowicz JR, Carter G, and Rao G (1994) Biotechnol. Bioeng 43, 1139–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sipior CJ, Randers-Eichhorn L, Lakowicz JR, Carter G, and Rao G (1996) Biotechnol. Prog 12, 266–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Randers-Eichhorn DL, Bartlett R, Frey D, and Rao G (1996) Biotechnol. Bioeng 51, 466–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gruber WR, O’Leary P, and Wolfbeis OS (1995) SPIE Proc. 2388, 148–158. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saidat-Pajouh M, Periasamy A, Ayscue AH, Moscicki AB, Palefsky JM, Walton L, DeMars LR, Power JD, Herman B, and Lockett SJ (1994) Cytometry 15, 245–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lakowicz JR, Szmacinski H, Nowaczyk K, Lederer WJ, Kirby MS, and Johnson ML (1994) Cell Calcium 15, 7–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lakowicz JR, Szmacinski H, Nowaczyk K, and Johnson ML (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 1271–1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Periasamy A, Wang XF, Wodnick P, Gordon GW, Kown S, Diliberto PA, and Herman B (1995) J.S.M.A 1(1), 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grigg R, and Amilaprasadh Norbert WDJ (1992) J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun, 1300–1302. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gould S, Strouse GF, and Sullivan BP Inorg. Chem 30, 2942–2949. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rawle SC, Moore P, and Alcock NW (1992) J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun, 684. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lakowicz JR, and Maliwal BP (1985) Biophys. Chem 21, 61–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lakowicz JR (Ed.) (1991) in Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Vol. 1, Techniques (Lakowicz JR, Ed.), pp. 293–355, Plenum Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsien RY (1989) Methods Cell Biol. 30, 127–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsien RY, and Poenie M (1986) Trends Biochem. Sci 11, 450–455. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szmacinski H, and Lakowicz JR (1993) Anal. Chem 65, 1668–1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whitaker JE, Haughland RP, and Prendergast FG (1991) Anal. Biochem 194, 330–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Terpetschnig E, Szmacinski H, Malak H, and Lakowicz JR (1995) Biophys. J 68, 342–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terpetschnig E, Szmacinski H, and Lakowicz JR (1995) Anal. Biochem 227, 140–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.(1992) Fed. Reg 57, 7002–70186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lakowicz JR, Szmacinski H, and Johnson ML (1992) J. Fluoresc 2(1), 47–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Szmacinski H, and Lakowicz JR (1996) Submitted for publication.

- 43.Szmacinski H, and Lakowicz JR (1995) Sens. Actuators B 29, 16–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Youn HJ, Terpetschnig E, Szmacinski H, and Lakowicz JR (1995) Anal. Biochem 232, 24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fantini S, Franceschini MA, Fishkin JB, Barbieri B, and Gratton E (1994) Appl. Optics 33(22), 5204–5213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lippitsch ME, and Wolfbeis OS (1988) Anal. Chim. Acta 205, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sipior J, Carter GM, Lakowicz JR, and Rao G (1996) Rev. Sci. Instrum 67(11), 3795–3798. [Google Scholar]