Abstract

It has now been ~30 years since the Alzheimer’s disease (AD) research entered what may be termed the “molecular era” that began with the identification of the amyloid β protein (Aβ) as the primary component of amyloid within senile plaques and cerebrovascular amyloid and the microtubule associated protein tau as the primary component of neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) in the AD brain. These pivotal discoveries and the subsequent genetic, pathological, and modeling studies supporting pivotal roles for tau and Aβ aggregation and accumulation have provided firm rationale for a new generation of AD therapies designed not to just provide symptomatic benefit, but as disease modifying agents that would slow or even reverse the disease course. Indeed, over the last 20 years numerous therapeutic strategies for disease modification have emerged, been preclinically validated, and advanced through various stages of clinical testing. Unfortunately, no therapy has yet to show significant clinical disease modification. In this review, I describe 10 translational barriers to successful disease modification, highlight current efforts addressing some of these barriers, and discuss how the field could focus future efforts to overcome barriers that are not major foci of current research efforts.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s Disease, therapeutics, amyloid, tau, prevention, brain organ failure, biomarkers, combination therapy, animal models, Amyloid precursor protein (APP)

Introduction

There is a pressing need to find more effective therapies for Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The world is facing a growing AD epidemic with almost 50 million individuals thought to be living with the disease today and projections suggest that by 2050 the number affected will exceed 120 million (Wimo et al. 2010, Alzheimer’s 2015). Unlike other major disease for which there has been steady progress with respect to development of novel therapies and, in most cases, reductions in incidence, for AD there are only modestly effective symptomatic therapies available. Indeed, the individual, societal and economic toll of AD is enormous and growing rapidly. For reference, if one put the current cost of care for AD in the context of gross domestic product, it would represent the economy of a country roughly the size of Turkey (Alzheimer’s 2015). Simply put, the unmet need is huge and growing.

Despite funding that has never been proportionate to the impact of the disease (Golde et al. 2011a), major advances in disease understanding have provided a strong foundation for development of novel therapies; however, as noted above, no disease modifying therapy has proven effective in clinical trials. There are many opinions as to why recent trials have failed, which have been extensively reviewed (Cummings et al. 2014, Karran et al. 2011, De Strooper & Chavez Gutierrez 2015, Golde et al. 2011b, Toyn 2015). In this review, I will identify some of the key challenges with respect to developing and testing novel therapies for AD, with a focus i) on refining the road map for therapeutic target discovery and development and ii) ensuring that we learn from our failures so that we might optimize our chances for future success.

Foundational Advances in Disease Understanding Provide Support for AD Prophylactic Therapies

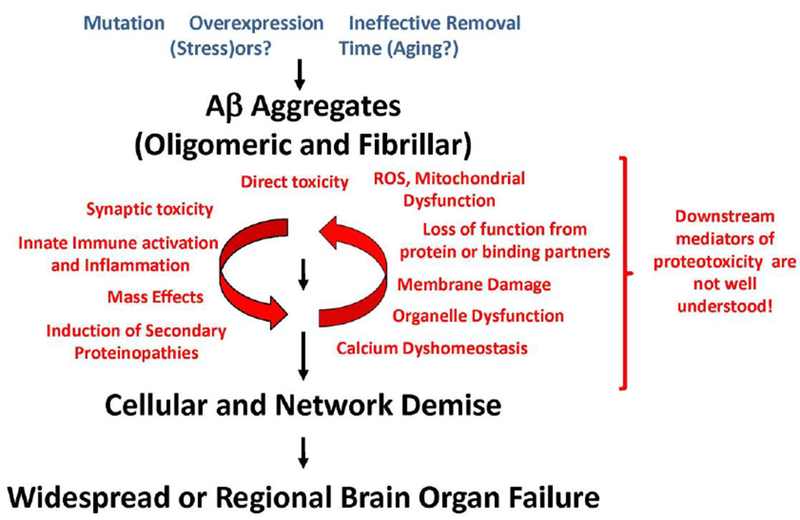

Although many areas of AD pathogenesis remain enigmatic, pathological, genetic, and modeling studies provide strong support for a modified version of the amyloid cascade hypothesis that i) accounts for the notion that many different aggregates contribute to downstream dysfunction and ii) the cascade is not linear (Figure 1) (Hardy & Selkoe 2002). For heritable forms of AD there is overwhelming evidence that accumulation of Aβ in aggregated, oligomeric or fibrillar forms, is the critical triggering event (Hardy & Selkoe 2002, Golde et al. 2011b). The recent demonstration that a rare genetic variant, which alters the coding sequence of Aβ and reduces Aβ production, reduces the risk for developing AD provides a counterexample of a mutation that does not confer risk, but, rather, protection from AD (Jonsson et al. 2012). This finding confirms the central role of Aβ in AD pathogenesis, but also provides compelling genetic data for prophylactic anti-Aβ therapies. Mutations in the MAPT gene encoding tau that cause NFT only dementia and subsequent modeling studies also support the critical role of tau in typical AD pathogenesis (Hutton et al. 1998, Hutton 2000, Lewis et al. 2000, Spillantini et al. 1998). Just as with Aβ, it is clear that different tau aggregates may contribute in distinct ways to disease progression (Takashima 2010, Zahs & Ashe 2013). Further, both cross-sectional postmortem studies and more recent cross-sectional and longitudinal human amyloid and tau imaging studies strongly support the sequential development of cortical amyloid followed by cortical tau pathology with the latter being much more highly correlated with cognitive deficits (Braak et al. 1996, Braak & Braak 1997, Jack et al. 2011, Jack et al. 2013). Thus, Aβ accumulation may be the initial trigger of AD, but cortical tau pathology is a needed for further damage. In other words, Aβ accumulation is the prerequisite “trigger,” but may not be , by itself, sufficient for AD. Additional hits such as induction of tau pathology are likely required to trigger overtly symptomatic disease. Overall, these studies indicate that AD is characterized by a long prodromal or presymptomatic phase in which these and other pathologies spread and damage the brain. On average, this prodromal phase is thought to precede the development of symptoms by 20 years or more (Patterson et al. 2015). Thus, by the time an individual presents with overt symptoms of AD (or even mild-cognitive impairment (MCI) of the AD type), these proteinopathies have been longstanding and wreaked a huge amount of damage upon the brain.

Figure 1. A schematic of a modified and update amyloid cascade hypothesis.

This hypothesis differs from the original cascade hypothesis (Hardy & Selkoe 2002) in that it i) accounts for the contribution different forms of AB aggregates, II) it recognizes that downstream events leading to brain organ failure are not necessarily liner nor are they well understood, iii) that once a certain level of damage has occurred the downstream mediators of neurodegeneration may no longer be dependent on the triggering AB proteinopathy.

Although not a proteinopathy, atherosclerotic heart disease serves as an excellent example of another human disease caused by long-term accumulation of a metabolite. Cholesterol accumulation in coronary arteries occurs decades before symptoms. By targeting cholesterol early in life, statins and other medications have had a huge impact on atherosclerotic hear disease; however, lowering cholesterol in the setting of heart failure has minimal benefit (Zhang et al. 2011). Similarly, the amyloid hypothesis never predicted that altering amyloid deposition would actually have benefit in symptomatic AD; it only predicted that preventing amyloid accumulation would prevent AD. By inference, one would predict that intervention targeting Aβ accumulation will show decreasing efficacy as the underlying pathology progresses.

Notably, the scenario described above for AD is likely analogous for over 30 neurodegenerative proteinopathies including α-synuclein driven Parkinson’s disease, many forms of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and the numerous polyglutamine repeat disorders including Huntington’s disease and certain forms of spinocerebellar ataxia (Golde et al. 2013, Forman et al. 2004). This somewhat unexpected mechanistic convergence in terms of the proteinopathy, as a triggering mechanism for various neurodegenerative diseases, provides a solid foundation in which to collectively view these disorders. They are all fundamentally protein accumulation disorders, i.e., proteinopathies. As in AD, there is evidence that the protein accumulation precedes clinical symptoms in these other neurodegenerative disorders by many years if not decades. Thus, any therapy aimed at the underlying proteinopathy will be predicted to be more effective if the therapy is initiated long before the symptomatic phase of the disease, and most effective if the therapy is initiated before the development of pathology. Indeed, numerous preclinical studies demonstrate that therapies targeting the proteinopathy in transgenic mouse models are typically, but not always, much more effective as prophylactics or in the very earliest stages of the proteinopathy (Wang et al. 2011, Das et al. 2012, Demattos et al. 2012).

The AD field has recently responded to the issue of targeting Aβ accumulation too late in the disease process and moved multiple anti-Aβ therapies into “prevention” trials (Sperling et al. 2014, Reiman et al. 2011, Moulder et al. 2013). Although some of the studies may actually enroll cognitively normal patients without evidence for amyloid deposition, for the most part these trials are designed as secondary prevention studies. They are treating individuals who are not clearly symptomatic but have evidence for amyloid deposition by imaging. These prevention studies are huge efforts involving hundreds of investigators and thousands of study participants. All involved, but especially the study participants, should be praised for undertaking these logistically challenging and resource intensive efforts. Given the potential for major disease modifying effects of primary or secondary prevention strategies, these efforts are vital steps towards the long-term goal of greatly reducing the disease burden of AD.

Given both current preclinical and clinical data surrounding anti-Aβ therapies, it is reasonable to raise the issue of whether the field should continue to test anti-amyloid therapies in symptomatic individuals or even in individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) who are amyloid positive. Although I will address the broader issue of interventions for patients with symptomatic disease later in the review, there are reasons why, even with a low probability of success for major disease modifying effects, I believe current late stage anti-amyloid trials in symptomatic AD are warranted. The main reason is that none of the previous anti-amyloid trials targeting Aβ definitively showed that there was sufficient therapeutic target engagement to elicit an effect (Golde et al. 2011b). Thus, there has been no definitive testing of the hypothesis that targeting Aβ in symptomatic AD will have symptomatic benefit. Aducanumab is clearly the first antibody with the unique property of being highly Aβ aggregate selective and, in the recently reported Phase 1b study, clearly shows evidence for impressive reduction of amyloid load as assessed by PET imaging along with suggestive clinical data that it could have cognitive and functional benefit (Reardon 2015, Underwood 2015). The newly launched aducanumab phase 3 study will be closely watched, especially given the high incidence of amyloid related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) seen at higher does. Nevertheless, this seems to be the first data for any anti-Aβ antibody trial that shows real evidence for significant lowering of amyloid burden in a reasonable time frames. Although one might infer from the AN1792 that active immunization can clear “amyloid” and clearly did not alter clinical outcomes, the AN1792 data is based on much too small of sample set with no longitudinal imaging data and is, therefore, too anecdotal to have any predictive value (Holmes et al. 2008). Further, although bapineuzamb also appears to lower amyloid burden as assed by 11C-PiB imaging, the magnitude of the effect was relatively small (Liu et al. 2015). Of course, one caveat of these studies is that we still do not know how a reduction in amyloid ligand binding reflects changes in actually pathology. Solanezumab, an anti-Aβ antibody that does not bind aggregated forms but only soluble Aβ, also shows target engagement with respect to binding soluble Aβ in the CSF. The completed phase 3 studies supported a very modest clinical benefit that appears to persist in an open label extension study (Siemers et al. 2015, Siemers et al. 2010, Doody et al. 2014). Thus, the additional phase 3 study (EXPEDITION-3), in patients who truly have mild AD based on amyloid scans, appears warranted. As both of these antibodies test two different mechanisms, they provide incredibly important tests of Aβ immunotherapies in symptomatic AD and should be powered sufficiently to provide important information regardless of outcome. A similar rationale supports the ongoing studies of the phase 3 trial with the BACE1 inhibitor, verubecestat (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01953601). The hypothesis that lowering Aβ production in symptomatic AD will have clinical benefit has also not been tested with any degree of certainty. Although preclinical studies would suggest that lowering Aβ production in individuals with overt neurodegeneration and massive amyloid deposition is not likely to impact disease, some preclinical models would suggest that Aβ toxicity is, in part, related to ongoing fibril growth. Thus, one could envision some benefit with sufficient lowering of soluble Aβ levels, such as appears to be achieved with verubecestat. Again, this is a large, well-powered phase 3 study that should provide a definitive answer to this question, as target engagement will not be in question.

Obstacle 1: Safe, Affordable Effective Enough Therapies for Prophylactic Therapy.

Currently, only anti-amyloid therapies are being evaluated in the various prevention studies. Three anti-Aβ antibodies, crenezumab, gantenerumab and solanezumab, are currently being utilized, but it is likely that other antibodies will also be tested (e.g., aducanumab) (Sperling et al. 2014, Reiman et al. 2011, Moulder et al. 2013). Both solanezumab and crenezumab clearly meet the safe enough criteria to be more widely deployed if they show efficacy (Garber 2012, Doody et al. 2014). In contrast, gantenerumab and other antibodies that are associated with ARIA may face some challenges in meeting the safe enough criteria; however, one might also predict that incidence of ARIA may be greatly reduced simply because the amyloid load is much lower in the subjects enrolled in these prevention studies. The real issue that I foresee with a passive immunotherapy approach is that it may not be affordable. If therapy needs to be continuous and requires multiple doses over many years, this therapy will be challenging enough to deploy widely, even in wealthy countries, due to financial considerations. It is possible that a “roto-rooter-like” effect could be observed with an optimized antibody, where only a few doses would be sufficient to reduce Aβ to the degree that disease is slowed for many years, making the therapy more affordable and practical; however, this degree of efficacy with limited dosing is at this point pure speculation.

One active vaccine CAD-106 and one BACE1 inhibitor (JNJ-54861911, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02260674) are also being evaluated in these prevention studies (Panza et al. 2014, Farlow et al. 2015). Clearly, an active vaccination approach can obviate concerns about affordability of therapy. Even if multiple boosts are necessary, cost should not be an issue. A major concern is the efficacy of vaccines such as CAD-106 that are designed to be and appear to be “safe enough”. CAD-106 is composed of the Aβ1-6 peptide derived from the N-terminal B cell epitope of Aβ, coupled to a Qβ virus-like particle. Titers elicited with this vaccine are modest and it is unclear whether such modest titers can result in target engagement in the brain (Winblad et al. 2012). Indeed, with a limited Aβ epitope that is found on numerous amyloid precursor protein (APP) derivatives besides Aβ, one might expect limited ability for modest levels of circulating antibodies with variable affinities to engage Aβ in the brain. Given that no peptide based vaccine approach has proven efficacious enough for approval for any human disease indication, one must wonder whether these approaches to use defined epitopes of Aβ will ever prove successful (Voskens et al. 2009). A small-molecule approach would also likely be cost effective; however, the main concern with BACE1 inhibitors is the lingering issue of both off-target and on-target toxicity. As opposed to antibodies which might be able to reverse preexisting deposition, BACE1 inhibitors would likely need to be continuously dosed. Given the growing recognition of BACE1 in regulation of important biological functions due to its numerous substrates, and unknowns regarding long-term treatment with such inhibitors, only time will tell whether the current BACE1 inhibitors are safe enough (Yan & Vassar 2014, Vassar et al. 2014). If they do prove safe enough, then preclinical studies would support use in primary prevention.

Ultimately, from public health perspectives, vaccines make the most sense in terms of likelihood to have major impact on disease and also be cost-effective; however, immunizing against a self-epitope poses challenges both from a safety perspective in terms of induction of a harmful immune response and in breaking immune tolerance. Given that the most rational targets for anti-Aβ immunotherapy are the aggregated forms of Aβ and not the monomers (Levites et al. 2006), many groups are exploring ways to induce conformer specific immune responses (Wisniewski & Goni 2015). Although theoretically feasible, development of such vaccine has been challenging and worthy of continued investigation.

Obstacle 2. Cost of clinical trials and length of time needed to enroll.

Current cost for phase 3 trials in AD typically exceed $100 million dollars and most cost much more ($350-$500 million+), especially if they involve multiple amyloid scans and other imaging studies. Despite the likely blockbuster status (with predicted sales of multiple billions of dollars per year of any newly approved AD therapeutic with evidence for disease modification) the huge investment necessary to test a new therapeutic and the lack of predicative value for success based on phase II data are daunting obstacles that loom over the field. Although there was some reduced private sector investment following several phase 3 failures reported from 2008-2010, we are witnessing renewed investment with respect to development and testing of disease modifying AD therapies. If current trials are not successful, then we may once again see a major pull back in private sector research and development for AD therapeutics. In contrast, if trials could be run for much reduced costs with better predictive value especially in early stages of testing, it is likely that there will be continued investment.

Although there are no simple solutions to how one reduces the costs of trials, one general thought is that the current paradigm is to look for very subtle effects in very large and somewhat heterogeneous populations. Indeed, most phase 3 studies are powered to observe effects on cognition (e.g. ~ 3 point change in ADAScog over 18 months) that may be statistically significant but of marginal clinical significance (Schneider et al. 2014). Perhaps, using smaller well-defined populations and looking for larger changes, even over longer periods of time, would enable more cost-effective trial paradigms. One puzzling issue with most trials is the length of time that it takes to enroll patients in a large phase III study (18-24 months); given the huge number of at risk individuals and those already affected with AD, one would think that concerted efforts to more efficiently recruit trial participants would have a huge impact. If pardigms could be put in place that reduce the clinical trial life-cycle by 2-3 years from phase 1-3, there could be huge economic benefits for the companies developing AD drugs and also the more altruistic benefit of being able to test more drugs more efficiently. This issue has not gone unnoticed by the field and is finally getting more attention and funding. Hopefully, current efforts to create patient registries (http://www.brainhealthregistry.org/) as well as other novel recruitment models will help to decrease costs, increase efficiency and decrease length of enrollment for future AD trials.

Obstacle 3. Development of screening biomarkers to assess risk and predictive markers of progression.

One of the challenges of AD clinical trials is that current endpoints for approval require evidence for clinical benefit (Schneider et al. 2014). As both cognitive and functional assessments have inherent variance and can be confounded by factors other than treatment being evaluated, there has been a huge effort to find biomarkers for AD that can serve as surrogates for clinical endpoints (Hendrix et al. 2015, Weiner et al. 2015, Blennow 2004). The field has clearly been successful in developing disease state biomarkers (e.g., amyloid imaging or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ42:40 ratios and tau); however, the progress with respect to markers of progression that can serve as surrogates for clinical endpoints has not been as impressive. There is still hope that various imaging biomarkers such as volumetric change by MRI or the more recent tau imaging agents may enable disease progression to be tracked more quantitatively and with less confounds. Protein based biomarkers such as neurofilament proteins in CSF and blood also show some promise as measures of progression (Skillback et al. 2014, Blennow et al. 2012). However, in all cases, we are still caught in somewhat of a circular dilemma. Until one can show that a disease modifying agent works clinically and also moves the biomarker in a given direction, it is not possible to prove that the biomarker has real predictive power. Given the huge amount of biomarker data being collected in the ongoing prevention studies, as well as collection of samples that can be used to evaluate emerging novel biomarkers, I am personally optimistic that such biomarkers of progression will be validated and used to guide future therapeutic development by enabling more rapid decision making in early stage trials. Significantly, biomarkers of progression need not be specific for AD, as long as track with progressive neurodegeneration. In fact, their utility might be greater if they tracked progression in multiple diseases.

Given the best public health solution for AD is primary prevention, it is almost certain that we will need better markers for AD risk. This will likely involve some combination of genetics and other biomarkers. APOE4 status is clearly a major genetic risk factor for AD and could be a very useful screening tool (Roses 1994, Tsai et al. 1994). It is likely that current large scale sequencing efforts will also identify other genetic variants that can be used to more accurately predict one’s inherent risk for future development of AD (Karch & Goate 2015); however, the field still lacks something akin to cholesterol (LDL, HDL) and triglyceride levels in plasma as a simple cost effective primary screen for atherosclerotic risk. Given the poor track record of identifying reproducible blood-based biomarkers for the AD disease state, let alone risk for AD, this will likely be a challenging endeavor (Galasko & Golde 2013). Clearly, one of the biggest challenges in a peripheral biomarker is whether a change in the peripheral marker is an inherent part of the disease process or whether a reliable marker will only arise by focusing on markers in the periphery that originate in the CNS. Recent preliminary studies of putative AD biomarkers in CNS derived exosomes represent one intriguing example of how this challenging problem might be overcome through innovative approaches (Goetzl et al. 2015).

Obstacle #4. Recognition that AD is Brain Organ Failure and may require Combination Therapies to Treat Effectively.

The AD prevention initiatives underway are, for the reasons described above, rational, laudable, and the most likely path that will lead to the biggest public health impact; however, unless we are extremely lucky and an optimal therapeutic agent is currently in a prevention trial or in late stage development, at least another generation or two, representing tens of millions of individuals, will develop and suffer from AD. Indeed, the more likely scenario with respect to AD prevention is that we will make transformative, but, nevertheless, incremental inroads. Initial therapies will slow the development of AD and slow progression, but will not be 100% effective. Thus, individuals will still get AD; they will just be a little older and maybe progress a little more slowly. For these reasons, it is nether ethical or strategically appropriate to move all efforts to prevention. We must collectively continue to try to develop therapies that will be effective to individuals who are symptomatic.

There are numerous challenges, however, to development of more effective therapies for symptomatic AD. I have intentionally used the word brain organ failure to describe AD to reflect the fact that by the time one shows symptoms of AD or even MCI, a huge amount of damage has been done to the brain. The pioneering neurochemical studies showing massive cholinergic and other neurotransmitter deficits in the AD brain are just one example of the massive disruption of brain function that underlies cognitive impairments (reviewed in (Davies & Wolozin 1987)). It is my own belief that until we begin to view AD as brain organ failure and implement therapeutic approaches that are analogous to how we treat peripheral organ failure, AD therapies will have minimal impact on the disease course in symptomatic patients. Indeed, statins do not show efficacy in the setting of heart failure, even though they still lower cholesterol in those individuals. By analogy, in AD it may be too late for trigger targeting therapies.

Further, the idea that a single therapy will have significant clinical impact in AD is not supported by any previous clinical study nor, by inference, from treatment of peripheral organ failure. The underlying therapeutic inference from calling AD “brain organ failure” is that to develop effective therapies for symptomatic AD we may need to develop a combination approach from the start. Notably, this conceptual inference is beginning to gather some momentum. Alternative approaches to combination therapy are to identify therapeutic targets (e.g., histone deacetylases, calpain inhibition, transcription factors) whose modulation results in multiple beneficial effects or develop single therapies with multiple targets. All of these approaches, for reasons elaborated to some extent in sections below, face many challenges. For combination therapies there is also very limited preclinical proof of concept, beyond the demonstration of showing that one can get additive or, perhaps, synergistic effects by utilizing different anti-Aβ therapies (e.g. an antibody plus a BACE1 inhibitor) (Stephenson et al. 2015). Although it can be argued that combination therapies in symptomatic patients might still consist of trigger targeting therapies plus other therapies with distinct mechanism of action, the disease triggers may play little or no role in later disease stages. Thus, when I think about future combination therapies, I envision multiple therapies aimed at restoring proteostasis, providing trophic support, altering innate immunity, providing cognitive enhancement or some combination of these approaches. However, given the unmet medical need, we must develop both preclinical and clinical road maps, which support the development of combination therapies. Of course testing such combinations in elderly individuals, who may already be taken multiple medications for other indications, will be inherently challenging.

Obstacle #5. Gaining Insights into the Mechanisms that Lead to Brain Organ Failure in AD.

Despite reasonable consensus in the field that the key triggering events in AD are the development of the Aβ and tau proteinopathies, there is considerable uncertainty as to how these proteinopathies lead to brain organ failure (Figure 1) (Golde et al. 2013). Perhaps one of the biggest challenges the field faces for developing novel therapies that would work in symptomatic patients is understanding the pathobiological processes that follow the triggering proteinopathies. We simply do not have sufficient biologic insight into what processes we may want to target.

Aβ aggregates can be shown to have a plethora of toxic properties in various model systems, yet large amounts of Aβ accumulate in the forebrain a decade or more before an individual becomes overtly symptomatic. Some have argued that this may be attributable to differential accumulation of various types of Aβ aggregates (Zahs & Ashe 2013, Shankar et al. 2008, Walsh et al. 2002). Despite intensive effort to define the toxic Aβ peptide aggregates, there remains little consensus in the field as to which aggregates are the true pathogens. Perhaps he only consensus statement one can make is Aβ42 is more toxic than Aβ40 due to its propensity to aggregate (Golde et al. 2011b). Although it is possible that some specific soluble oligomeric assembly is the primary toxin, it is more likely that different aggregates of Aβ provide a collective toxic insult through different mechanisms. Indeed, much of the effort in the field has been focused on Aβ aggregates and their effect on neurons, but, again, AD is not just a disease of neuronal degeneration. All cell types in the brain, including but not limited to neurons, astrocytes, microglia, oligodendroglia and endothelial cells are altered during the development of AD. Though oligomers may have more potent effects on synaptic physiology than fibrils (Zahs & Ashe 2013), they are not overtly toxic, and, for example, in contrast to what happens to neurons, fibrils may be more potent activators of microglial cells than oligomers (Ferrera et al. 2014).

Uncertainties regarding cause and effect become even more evident as one begins to explore the mechanisms downstream of the triggers leading to brain organ failure. There are varying levels of evidence implicating synaptic failure, dystrophic neurites, mitochondrial dysfunction, calcium dysregulation, changes in innate immune activation state, lipid metabolism, axonal transport, endosomal dysfunction, endoplasmic reticulum stress and other factors as drivers of neurodegeneration (Golde & Miller 2009, Aguzzi & O’Connor 2010). In reality, dysfunction in many of these pathways likely collectively contribute to brain organ failure. So how does one prioritize targeting these factors in terms of developing a new therapeutic target? Genetics may or may not help. Indeed, genetic insights such as those provided by TREM2 functional variants may provide clues about downstream innate immune activation cascades in AD (Pottier et al. 2013, Jonsson et al. 2013), but they may also simply point us back to role of innate immunity in regulating the triggering proteinopathy (Wang et al. 2015, Tanzi 2015, Jay et al. 2015). Nevertheless, at least when functional variants that alter AD risk are identified, we must pursue these in the hopes that they will provide new insights that are actionable in terms of therapeutic development for AD.

Obstacle 6. Our Models of AD are Imperfect.

One of the reasons that we have less insight into the biological process downstream of the triggering proteinopathies in AD is that our models system used to study AD pathobiology are only imperfect phenocopies of human AD (Price & Sisodia 1998, LaFerla & Green 2012). None of these models should be called models of AD, but models of AD-like pathologies. Amyloid precursor protein (APP) transgenic mice and other genetic manipulations that drive Aβ aggregate accumulation model amyloid deposition well. They also model neuritic dystrophy and reactive gliosis reasonably well. However, it is unclear whether the cognitive impairments in these mice reflect cognitive impairment in AD. Indeed, in the absence of overt neurodegeneration and tau pathology, Aβ deposition in humans is not associated with significant cognitive dysfunction. APP mice do not develop marked degenerative changes, tau pathology, or huge cholinergic neurotransmitter deficits seen in human AD (LaFerla & Green 2012). Further, MAPT (tau) transgenic mice that develop robust pathology are largely based on mutations that cause frontal temporal dementia with parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTD-MAPT) (LaFerla & Green 2012). Are these models of AD or FTD-MAPT? Many mutant tau transgenic mice do show degenerative changes, but these occur rapidly and require massive overexpression of the tau transgenes. Thus, relevance to tau pathology in AD remains uncertain.

Recent efforts to improve Aβ deposition models in the hopes that they might lead to more robust models of downstream AD pathologies, have met with limited success. APP transgenic rats may show slightly more degenerative changes and slightly more tau pathology, but it’s unclear if the advantages of a rat model are sufficient to overcome the increases in resources needed to utilize these models (Cohen et al. 2013). A Knock in model develops Aβ deposition and may be less confounded by APP overexpression than other models, but also fail to more fully phenocopy human AD (Saito et al. 2014). Thus, it is uncertain, after 20 plus years of developing rodent models of AD based on driving Aβ pathology, whether a better model will emerge from additional efforts. Perhaps new genetic engineering tools or viral methods will enable one to develop a more robust AD model based on APP or Aβ transgenes in some other mammal. However, such future attempts should be tempered by studies that showing that even aged non-human primates that develop modest Aβ deposition do not have much evidence for additional pathologies -even if inoculated with extracts from AD brain that can accelerate amyloid deposition (Heuer et al. 2012).

Given the recent emphasis on tau based therapies, it is likely that more investment in tau models might be warranted. The hTau mice that contain a human BAC and express all of the non-mutant human tau isoforms in the context of a mouse Mapt knockout background develop limited tau pathology over long periods of time (Andorfer et al. 2005). Similar, but more robust models might be useful for the field as they might be better models of human AD tau pathology than the FTDP17 based models. Indeed, the vast majority of tau transgenic models that are widely used are based on either the P301L or P301S MAPT mutations; it is not even clear that these mutations are representative of tau dysfunction in all forms of FTD-MAPT let alone tau dysfunction in AD.

Although some are nihilistic about the lack of utility of mouse models, in general these models are highly useful when used with a clear understanding of their limitations and their informativeness with respect to human AD. Some of the nihilism derives from the lack of predicative value in studying the mouse model with respect to effects observed when a therapy which shows efficacy in the mouse model fails to show efficacy in humans. However, the vast majority of such failures in translation can be rationally attributed to the failure to align the clinical and preclinical studies (Golde et al. 2011b). APP mice do not model symptomatic AD; they model amyloid deposition and maybe some aspects of prodromal AD. Most interventions tested in these models that have advanced to the clinic alter Aβ deposition in the preclinical studies, but only if the treatment is initiated before the mice have AD-like amyloid loads. But in humans the therapy has been tested in symptomatic patients with long-standing amyloid accumulation. Further, even those therapies that have been tested in mice with AD-like amyloid loads and shown to alter Aβ, primarily alter diffuse but not compact plaques (Demattos et al. 2012, Wang et al. 2011). Thus, even reports of robust efficacy in such models must be viewed with some objectivity, as the pathological implications of diffuse Aβ and its removal are unclear.

Clearly, mice are not the only model organism that can be used to model proteinopathies relevant to AD. Drosophila, C. Elegans, and even yeast models have been used to gain insights into Aβ and tau toxicity (Link 2005, Bilen & Bonini 2005, Muqit & Feany 2002, Winderickx et al. 2008, Prussing et al. 2013, Li & Le 2013). Screens, either genetic or small molecule, in these model organisms have yielded some novel insights into how these proteins may exert their toxicity, though it is unclear in most cases how relevant this is to human disease. As with the mouse models, nihilism about the use of such models is not beneficial. Many additional steps may be required to validate a biological pathway or putative therapeutic target identified in one of these models into findings that are widely accepted to have relevance to human AD, but given the need for new targets and novel insights such efforts are warranted.

Of course, mice do not always model human physiology and there has been quite a bit of excitement about using human derived iPSC neuronal cultures or other CNS cell types to model AD pathologies (Choi & Tanzi 2012, Livesey 2014, Ross & Akimov 2014). These initial studies suggest that iPSC derived human neuronal cultures might prove a useful complement to existing models and might provide novel insight, for example, into the relationship between Aβ and tau. Indeed, such systems may provide highly useful to model complex genetic interplay that would be hard to model except by deriving such cultures from cells isolated from individuals with defined genetic risk factors associated with AD. However, the use of cultured human derived central nervous system-like cells is still in its early phases and the ultimate impact on the field uncertain. One major challenge will, again, be mimicking the unique brain microenvironment and interconnectedness of numerous different cell types within these culture models.

Obstacle 7: Understanding and Accounting for the Impact of Age and other Comorbidities on AD.

Age is the biggest demographic risk factor for development of AD (Alzheimer’s 2015). Despite intriguing studies that suggest that physiologic changes that occur with age, i.e., aging effects, may account for the association between advanced age and risk for AD, there is no definitive evidence that aging, as opposed to age, contributes to AD pathology. Indeed, genetics can trump any aging effect; genetically driven elevation of Aβ42 can lead to AD in the third decade of life. Despite this caveat that age and not aging is definitively associated with AD risk, it is certainly reasonable to propose that an aging brain is more vulnerable to the triggering AD proteinopathies or downstream insults and one could also envision how aging compromises clearance mechanism, again predisposing to the proteinopathy (Yankner et al. 2008, Bishop et al. 2010, Burke & Barnes 2006). Indeed, there is some, albeit limited, data that this may be the case. For example, injection of Aβ into an aged monkey brain caused much more damage than in a young brain (Geula et al. 1998). Further, there is evidence that opposed to early onset genetic forms of AD, which are for the most part linked to alterations in Aβ production, at least some forms of late onset AD may be linked to changes in Aβ clearance (Patterson et al. 2015). Whether effects of aging, altered Aβ clearance, or other non-genetic factors are captured in current models is uncertain.

More generally, it is important to recognize that AD is not necessarily a perfectly homogenous disorder and because it occurs most commonly in the elderly there are often significant comorbidities that create a much more complex clinical picture (Reitz et al. 2011, Chui et al. 2012). There are now many reports showing both clinical and pathological subtypes of AD (Reitz et al. 2011, Montine et al. 2014, Snyder et al. 2015, Lam et al. 2013). These observations are often mutually reinforcing; the clinical phenotypes are, in fact, often related to differences in the pathology. Further, there are many other factors that contribute to cognitive dysfunction in the elderly. Vascular, metabolic and other comorbidities may or may not have synergistic effects or be drivers of the AD phenotype, but they can certainly create clinical confounds which could influence results in clinical trials if not accounted for sufficiently (Chui et al. 2012). Especially when looking at postmortem AD brains of those who die after age 80, the picture that emerges is that pure “classic” AD with just Aβ and tau pathology may be the exception rather than the rule (Murray et al. 2014, Josephs et al. 2015, Jellinger et al. 2015).

Perhaps, rather than primarily focusing on trying to continuously generate a new and better model based on genetic manipulation, we should try and create models that reflect the potential comorbidities seen in aged humans. Further, we may need to house our models in environments that mimic the real world, not necessarily the environmental isolation chambers that we typically use for housing our rodent models.

Obstacle 8. Little Insight into the Biological Underpinnings of Non-genetic Risk Modulators for AD.

It is hard to envision where the AD field would be without the genetic insights that were essential for guiding research over the last 25 years (Hardy 2009). Clearly, advances would have been much more limited; however, typical late onset AD is not a purely genetic disorder. It is clear that environmental factors can alter risk for AD and probably can also alter rates of progression (Reitz et al. 2011). As non-genetic risk factor may be more easily modifiable than underlying genetic alterations, one might hope that more definitive insights into how risk factors contribute to risk or progression of AD might provide novel insights that could guide future therapeutic interventions.

The challenge with pursuit of such environmental risk factors as leads for biologic understanding and perhaps therapeutic intervention is that they are most often simply epidemiologic associations that may be hard to reproduce and are prone to many confounds. Indeed, these associations should be viewed with the major caveat that the association is with dementia and not necessarily AD. In any epidemiologic study of AD, there will likely be a significant confound of non-AD dementia in the group classified as AD and an equally large confound of controls who have underlying AD pathology (if the study assesses dementia in those over age 65). With the advent and more widespread implementation of amyloid imaging, more precise insights may be possible, but this won’t occur for some time. Another challenge with these studies is that there is often a temporal dissociation between the associated risk factor and the development of AD. For example, past use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) has been reproducibly associated with reduced risk for dementia(Zandi & Breitner 2001, in t’ Veld et al. 2001), but therapeutic trials of NSAIDs in clinical AD have failed(Lyketsos et al. 2007). Based on such data one could still posit that NSAIDs are protective from AD, but like many agents may not have impact on the disease once established.

Despite the numerous challenges, there are reasons to pursue this avenue of research. If one can provide solid biologic underpinnings for the epidemiological association one may be able to develop novel therapies that are based on both the human data and biological insights gained in model systems. Indeed, future preclinical and translational human studies of how factors like infection, psychological stress, head trauma, and diet may provide important clues that could be harnessed into a novel intervention that may or may not be pharmacologic in nature. One interesting example of how relatively challenging epidemiologic data relating stress to risk of AD has gained a foothold in the AD research landscape are studies showing that stress promotes both Aβ and tau pathology in mice and does so through a corticotropin-releasing factor based mechanism(Greenberg et al. 2014, Kang et al. 2007, Carroll et al. 2011, Dong et al. 2012, Zhang et al. 2015, Park et al. 2015). Such data has led to studies examining the repurposing of agents that block CRF signaling as well as strategies supporting direct targeting of CRF (Zhang et al. 2015, Park et al. 2015).

Obstacle 9. The Streetlamp Effect in AD Research.

In research, the streetlamp effect refers to an observational bias where scientists look for whatever they are searching by looking where it is easiest (Freedman 2010). This bias is captured by a longstanding joke about a policeman who sees a drunk man searching for something under a streetlamp and asks what he is looking for. He says he lost his keys and the policeman helps him look under the streetlamp for them, but a few minutes later the policeman asks did you “lose your keys here,” and the drunk says “no, I lost them in the park.” The policeman asks why he is searching here and the drunk replies, “it’s dark there I can’t see anything and this is where the light is.”

If one looks broadly at currently funded AD research, the portfolio is very conservative and has been for many years. Although grant funding agencies often try to solicit more innovative and transformative research, this is often undercut by review panels, who tend to fund science that is largely “under the streetlamp.” It is rare that researchers are funded to look in the shadows for those truly transformative discoveries or are funded to address some of the most challenging questions in the field.

There is obviously a much longer long list of research topics, which are clearly relevant to understanding of AD and could also impact future therapeutic development. I will limit my discussion to those areas of investigation, I find to be intriguing, that have not discussed previously in this review, and are not under the streetlamp as evidenced by the number of manuscripts published in that area and the number of grants funded.

Although it is clear that tau pathology can arise independently of Aβ, most in the field believe that in the AD brain Aβ accumulation somehow accelerates tau pathology. This is certainly supported by postmortem studies and, more recently, emerging tau imaging data (Hendrix et al. 2015, Weiner et al. 2015). Though some experimental evidence from transgenic mice and also human iPSC derived neurons supports this assertion (Choi & Tanzi 2012, Lewis et al. 2001, Gotz et al. 2001), the mechanistic link between the two remains relatively unexplored. Despite the fact that identifying the mechanisms by which Aβ would drive tau pathology would likely identify new therapeutic targets, there are few groups focused on this issue and even fewer funded grants trying to answer the question of “How Aβ talks to tau?”

A second question that is also underfunded and underexplored is “What is a dystrophic neurite?” Though a few groups are engaged in the study of these abnormal apparently axonal structures (Prior et al. 2010, Grace & Busciglio 2003), again, funding in this area is limited. Given that neuritic plaques are the truly defining hallmark of AD pathology, one would think that understanding the relationship between Aβ accumulation and development of these dystrophies would provide mechanistic insight into the neurodegenerative cascade and provide insights into another potential pathway for discovery of new therapies.

A third question is “What underlies selective neuronal vulnerability?” This question is germane not only to AD but the entire field of neurodegenerative disorders. Further, given the emerging interest in the role of non-neuronal cells in neurodegenerative cascades one might also extend the questions to other brain cell types. Again, there is limited funding and limited investigation in this area, but if one could understand why certain cells die and others do not, then one might have a clear path to a new therapeutic target.

Again, the list of underfunded and underexplored questions is much longer than these three examples and others mentioned in the course of this review. It is also important to acknowledge that the streetlamp effect has its merits. There are logical “well-illuminated” next steps in research that must also be funded. It is also a challenge for reviewers to endorse research that may be in the shadows or the dark, but lacks the rigor or thought that is actually necessary to move an area of investigation from the shadows into the light.

Obstacle 10: Limited Funding.

One reason for the conservative, “under the streetlamp,” AD research portfolio has been the relatively restricted funding that supports AD research. When funds are limited the most innovative ideas often go unfunded. As noted in the introductory paragraphs, funding for AD research has never been proportional to the impact of the disease. In the United States, we spend approximately 0.4% of the annual costs of this disease on research and the relative research expenditures are likely similar, or even less, in most industrialized nations. In order to ensure success in bringing advances from the bench to the bedside, we need more funding to insure that not just the most obvious studies are supported, but also the risky research that could be truly transformational. Significantly, advocacy efforts are beginning to make a difference. Ways to reduce the public health burden of AD is now part of the policy discussion at major worldwide economic summits and some countries have begun to increase their investment in AD research. Indeed, the United States just made an unprecedented increase to the National Institute of Health’s Alzheimer’s disease research budget of ~$350M per year.

Although often not part of our training as physicians and scientist, it is important that we participate in these advocacy efforts. The increase in funded and increased awareness about AD and its impact are perhaps the single most encouraging development in the field and we need to ensure that these upticks in funding and societal visibility are long-lasting. AD is not going to be cured overnight and we need a sustained and lasting translational research effort to ensure that we overcome the many obstacles to successful translation of knowledge about the disease to therapies that benefit patients.

Acknowledgments

TEG is supported by grants from the NIH (AG018454, AG046139, AG047266)

Abbreviations used:

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Aβ

amyloid β protein

- NFT

neurofibrillary tangles

- MAPT

microtubule associated protein tau

- BACE1

β-amyloid cleaving enzyme 1

- ADAScog

Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale. – Cognition

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- FTDP17

frontal temporal dementia with parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17

Footnotes

I have no competing interests.

References

- Aguzzi A and O’Connor T (2010) Protein aggregation diseases: pathogenicity and therapeutic perspectives. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 9, 237–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s A (2015) 2015 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement, 11, 332–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andorfer C, Acker CM, Kress Y, Hof PR, Duff K and Davies P (2005) Cell-cycle reentry and cell death in transgenic mice expressing nonmutant human tau isoforms. J Neurosci, 25, 5446–5454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilen J and Bonini NM (2005) Drosophila as a model for human neurodegenerative disease. Annual review of genetics, 39, 153–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop NA, Lu T and Yankner BA (2010) Neural mechanisms of ageing and cognitive decline. Nature, 464, 529–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blennow K (2004) Cerebrospinal fluid protein biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroRx, 1, 213–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blennow K, Zetterberg H and Fagan AM (2012) Fluid biomarkers in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine, 2, a006221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H and Braak E (1997) Frequency of stages of Alzheimer-related lesions in different age categories. Neurobiol Aging, 18, 351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E, Bohl J and Reintjes R (1996) Age, neurofibrillary changes, A beta-amyloid and the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett, 210, 87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke SN and Barnes CA (2006) Neural plasticity in the ageing brain. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 7, 30–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JC, Iba M, Bangasser DA, Valentino RJ, James MJ, Brunden KR, Lee VM and Trojanowski JQ (2011) Chronic stress exacerbates tau pathology, neurodegeneration, and cognitive performance through a corticotropin-releasing factor receptor-dependent mechanism in a transgenic mouse model of tauopathy. J Neurosci, 31, 14436–14449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SH and Tanzi RE (2012) iPSCs to the rescue in Alzheimer’s research. Cell stem cell, 10, 235–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chui HC, Zheng L, Reed BR, Vinters HV and Mack WJ (2012) Vascular risk factors and Alzheimer’s disease: are these risk factors for plaques and tangles or for concomitant vascular pathology that increases the likelihood of dementia? An evidence-based review. Alzheimers Research & Therapy, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RM, Rezai-Zadeh K, Weitz TM et al. (2013) A transgenic Alzheimer rat with plaques, tau pathology, behavioral impairment, oligomeric abeta, and frank neuronal loss. J Neurosci, 33, 6245–6256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JL, Morstorf T and Zhong K (2014) Alzheimer’s disease drug-development pipeline: few candidates, frequent failures. Alzheimers Res Ther, 6, 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das P, Verbeeck C, Minter L et al. (2012) Transient pharmacologic lowering of Abeta production prior to deposition results in sustained reduction of amyloid plaque pathology. Mol Neurodegener, 7, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P and Wolozin BL (1987) Recent advances in the neurochemistry of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Clin. Psychiatry, 48, 23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Strooper B and Chavez Gutierrez L (2015) Learning by failing: ideas and concepts to tackle gamma-secretases in Alzheimer’s disease and beyond. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology, 55, 419–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demattos RB, Lu J, Tang Y et al. (2012) A plaque-specific antibody clears existing beta-amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease mice. Neuron, 76, 908–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H, Murphy KM, Meng L, Montalvo-Ortiz J, Zeng Z, Kolber BJ, Zhang S, Muglia LJ and Csernansky JG (2012) Corticotrophin releasing factor accelerates neuropathology and cognitive decline in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis, 28, 579–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doody RS, Thomas RG, Farlow M et al. (2014) Phase 3 trials of solanezumab for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med, 370, 311–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farlow MR, Andreasen N, Riviere ME, Vostiar I, Vitaliti A, Sovago J, Caputo A, Winblad B and Graf A (2015) Long-term treatment with active Abeta immunotherapy with CAD106 in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther, 7, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera D, Mazzaro N, Canale C and Gasparini L (2014) Resting microglia react to Abeta42 fibrils but do not detect oligomers or oligomer-induced neuronal damage. Neurobiol Aging, 35, 2444–2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman MS, Trojanowski JQ and Lee VM (2004) Neurodegenerative diseases: a decade of discoveries paves the way for therapeutic breakthroughs. Nat Med, 10, 1055–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman DH (2010) The Streetlight Effect. Discover Magazine, July August 2010 issue. [Google Scholar]

- Galasko D and Golde TE (2013) Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease in plasma, serum and blood - conceptual and practical problems. Alzheimers Res Ther, 5, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber K (2012) Genentech’s Alzheimer’s antibody trial to study disease prevention. Nat Biotechnol, 30, 731–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geula C, Wu CK, Saroff D, Lorenzo A, Yuan M and Yankner BA (1998) Aging renders the brain vulnerable to amyloid beta-protein neurotoxicity. Nat Med, 4, 827–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetzl EJ, Boxer A, Schwartz JB, Abner EL, Petersen RC, Miller BL and Kapogiannis D (2015) Altered lysosomal proteins in neural-derived plasma exosomes in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurology, 85, 40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golde TE, Borchelt DR, Giasson BI and Lewis J (2013) Thinking laterally about neurodegenerative proteinopathies. J Clin Invest, 123, 1847–1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golde TE, Lamb BT and Galasko D (2011a) Right sizing funding for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther, 3, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golde TE and Miller VM (2009) Proteinopathy-induced neuronal senescence: a hypothesis for brain failure in Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. Alzheimers Res Ther, 1, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golde TE, Schneider LS and Koo EH (2011b) Anti-abeta therapeutics in Alzheimer’s disease: the need for a paradigm shift. Neuron, 69, 203–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotz J, Chen F, van Dorpe J and Nitsch RM (2001) Formation of neurofibrillary tangles in P301l tau transgenic mice induced by Abeta 42 fibrils. Science, 293, 1491–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace EA and Busciglio J (2003) Aberrant activation of focal adhesion proteins mediates fibrillar amyloid beta-induced neuronal dystrophy. J Neurosci, 23, 493–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MS, Tanev K, Marin MF and Pitman RK (2014) Stress, PTSD, and dementia. Alzheimers Dement, 10, S155–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J (2009) The amyloid hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease: a critical reappraisal. J Neurochem. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J and Selkoe DJ (2002) The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science, 297, 353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix JA, Finger B, Weiner MW et al. (2015) The Worldwide Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: An update. Alzheimers Dement, 11, 850–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuer E, Rosen RF, Cintron A and Walker LC (2012) Nonhuman primate models of Alzheimer-like cerebral proteopathy. Current pharmaceutical design, 18, 1159–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes C, Boche D, Wilkinson D et al. (2008) Long-term effects of Abeta42 immunisation in Alzheimer’s disease: follow-up of a randomised, placebo-controlled phase I trial. Lancet, 372, 216–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton M (2000) Molecular genetics of chromosome 17 tauopathies. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 920, 63–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton M, Lendon CL, Rizzu P et al. (1998) Association of missense and 5’-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature, 393, 702–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- in t’ Veld BA, Ruitenberg A, Hofman A, Launer LJ, van Duijn CM, Stijnen T, Breteler MM and Stricker BH (2001) Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med, 345, 1515–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR Jr., Knopman DS, Jagust WJ et al. (2013) Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol, 12, 207–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR Jr., Vemuri P, Wiste HJ et al. (2011) Evidence for ordering of Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Arch Neurol, 68, 1526–1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay TR, Miller CM, Cheng PJ et al. (2015) TREM2 deficiency eliminates TREM2+ inflammatory macrophages and ameliorates pathology in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. J Exp Med, 212, 287–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellinger KA, Alafuzoff I, Attems J et al. (2015) PART, a distinct tauopathy, different from classical sporadic Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol, 129, 757–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson T, Atwal JK, Steinberg S et al. (2012) A mutation in APP protects against Alzheimer’s disease and age-related cognitive decline. Nature, 488, 96–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson T, Stefansson H, Steinberg S et al. (2013) Variant of TREM2 associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med, 368, 107–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Tosakulwong N et al. (2015) TAR DNA-binding protein 43 and pathological subtype of Alzheimer’s disease impact clinical features. Ann Neurol, 78, 697–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JE, Cirrito JR, Dong H, Csernansky JG and Holtzman DM (2007) Acute stress increases interstitial fluid amyloid-beta via corticotropin-releasing factor and neuronal activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 104, 10673–10678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karch CM and Goate AM (2015) Alzheimer’s disease risk genes and mechanisms of disease pathogenesis. Biol Psychiatry, 77, 43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karran E, Mercken M and De Strooper B (2011) The amyloid cascade hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease: an appraisal for the development of therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 10, 698–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFerla FM and Green KN (2012) Animal models of Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam B, Masellis M, Freedman M, Stuss DT and Black SE (2013) Clinical, imaging, and pathological heterogeneity of the Alzheimer’s disease syndrome. Alzheimers Res Ther, 5, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levites Y, Smithson LA, Price RW et al. (2006) Insights into the mechanisms of action of anti-Abeta antibodies in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Faseb J, 20, 2576–2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J, Dickson DW, Lin WL et al. (2001) Enhanced neurofibrillary degeneration in transgenic mice expressing mutant tau and APP. Science, 293, 1487–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J, McGowan E, Rockwood J et al. (2000) Neurofibrillary tangles, amyotrophy and progressive motor disturbance in mice expressing mutant (P301L) tau protein. Nat Genet, 25, 402–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J and Le W (2013) Modeling neurodegenerative diseases in Caenorhabditis elegans. Exp Neurol, 250, 94–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link CD (2005) Invertebrate models of Alzheimer’s disease. Genes, brain, and behavior, 4, 147–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu E, Schmidt ME, Margolin R et al. (2015) Amyloid-beta 11C-PiB-PET imaging results from 2 randomized bapineuzumab phase 3 AD trials. Neurology, 85, 692–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesey FJ (2014) Human stem cell models of dementia. Hum Mol Genet, 23, R35–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos CG, Breitner JC, Green RC, Martin BK, Meinert C, Piantadosi S and Sabbagh M (2007) Naproxen and celecoxib do not prevent AD in early results from a randomized controlled trial. Neurology, 68, 1800–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montine TJ, Koroshetz WJ, Babcock D et al. (2014) Recommendations of the Alzheimer’s disease-related dementias conference. Neurology, 83, 851–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulder KL, Snider BJ, Mills SL, Buckles VD, Santacruz AM, Bateman RJ and Morris JC (2013) Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network: facilitating research and clinical trials. Alzheimers Res Ther, 5, 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muqit MM and Feany MB (2002) Modelling neurodegenerative diseases in Drosophila: a fruitful approach? Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 3, 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray ME, Cannon A, Graff-Radford NR et al. (2014) Differential clinicopathologic and genetic features of late-onset amnestic dementias. Acta Neuropathol, 128, 411–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panza F, Solfrizzi V, Imbimbo BP, Tortelli R, Santamato A and Logroscino G (2014) Amyloid-based immunotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease in the time of prevention trials: the way forward. Expert review of clinical immunology, 10, 405–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HJ, Ran Y, Jung JI et al. (2015) The stress response neuropeptide CRF increases amyloid-beta production by regulating gamma-secretase activity. EMBO J, 34, 1674–1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson BW, Elbert DL, Mawuenyega KG et al. (2015) Age and amyloid effects on human central nervous system amyloid-beta kinetics. Ann Neurol, 78, 439–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottier C, Wallon D, Rousseau S, Rovelet-Lecrux A, Richard AC, Rollin-Sillaire A, Frebourg T, Campion D and Hannequin D (2013) TREM2 R47H Variant as a Risk Factor for Early-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DL and Sisodia SS (1998) Mutant genes in familial Alzheimer’s disease and transgenic models. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 21, 479–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior M, Shi Q, Hu X, He W, Levey A and Yan R (2010) RTN/Nogo in forming Alzheimer’s neuritic plaques. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 34, 1201–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prussing K, Voigt A and Schulz JB (2013) Drosophila melanogaster as a model organism for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener, 8, 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon S (2015) Antibody drugs for Alzheimer’s show glimmers of promise. Nature, 523, 509–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiman EM, Langbaum JB, Fleisher AS et al. (2011) Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative: a plan to accelerate the evaluation of presymptomatic treatments. J Alzheimers Dis, 26 Suppl 3, 321–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitz C, Brayne C and Mayeux R (2011) Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol, 7, 137–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roses AD (1994) Apolipoprotein E affects the rate of Alzheimer disease expression: beta-amyloid burden is a secondary consequence dependent on APOE genotype and duration of disease [see comments]. [Review]. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology, 53, 429–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CA and Akimov SS (2014) Human-induced pluripotent stem cells: potential for neurodegenerative diseases. Hum Mol Genet, 23, R17–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito T, Matsuba Y, Mihira N, Takano J, Nilsson P, Itohara S, Iwata N and Saido TC (2014) Single App knock-in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci, 17, 661–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider LS, Mangialasche F, Andreasen N et al. (2014) Clinical trials and late-stage drug development for Alzheimer’s disease: an appraisal from 1984 to 2014. J Intern Med, 275, 251–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH et al. (2008) Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer’s brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med, 14, 837–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemers ER, Friedrich S, Dean RA, Gonzales CR, Farlow MR, Paul SM and Demattos RB (2010) Safety and changes in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid amyloid beta after a single administration of an amyloid beta monoclonal antibody in subjects with Alzheimer disease. Clin Neuropharmacol, 33, 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemers ER, Sundell KL, Carlson C et al. (2015) Phase 3 solanezumab trials: Secondary outcomes in mild Alzheimer’s disease patients. Alzheimers Dement. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skillback T, Farahmand B, Bartlett JW et al. (2014) CSF neurofilament light differs in neurodegenerative diseases and predicts severity and survival. Neurology, 83, 1945–1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder HM, Corriveau RA, Craft S et al. (2015) Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia including Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement, 11, 710–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, Karlawish J, Donohue M, Salmon DP and Aisen P (2014) The A4 study: stopping AD before symptoms begin? Sci Transl Med, 6, 228fs213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini MG, Murrell JR, Goedert M, Farlow MR, Klug A and Ghetti B (1998) Mutation in the tau gene in familial multiple system tauopathy with presenile dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 95, 7737–7741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson D, Perry D, Bens C et al. (2015) Charting a path toward combination therapy for Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev Neurother, 15, 107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima A (2010) Tau aggregation is a therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res, 7, 665–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzi RE (2015) TREM2 and Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease--Friend or Foe? N Engl J Med, 372, 2564–2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyn J (2015) What lessons can be learned from failed Alzheimer’s disease trials? Expert review of clinical pharmacology, 8, 267–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai MS, Tangalos EG, Petersen RC, Smith GE, Schaid DJ, Kokmen E, Ivnik RJ and Thibodeau SN (1994) Apolipoprotein E: risk factor for Alzheimer disease. American Journal of Human Genetics, 54, 643–649. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood E (2015) NEUROSCIENCE. Alzheimer’s amyloid theory gets modest boost. Science, 349, 464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassar R, Kuhn PH, Haass C, Kennedy ME, Rajendran L, Wong PC and Lichtenthaler SF (2014) Function, therapeutic potential and cell biology of BACE proteases: current status and future prospects. J Neurochem, 130, 4–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voskens CJ, Strome SE and Sewell DA (2009) Synthetic peptide-based cancer vaccines: lessons learned and hurdles to overcome. Current molecular medicine, 9, 683–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Rowan MJ and Selkoe DJ (2002) Amyloid-beta oligomers: their production, toxicity and therapeutic inhibition. Biochem Soc Trans, 30, 552–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang A, Das P, Switzer RC 3rd, Golde TE and Jankowsky JL (2011) Robust amyloid clearance in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease provides novel insights into the mechanism of amyloid-beta immunotherapy. J Neurosci, 31, 4124–4136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Cella M, Mallinson K et al. (2015) TREM2 lipid sensing sustains the microglial response in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Cell, 160, 1061–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner MW, Veitch DP, Aisen PS et al. (2015) Impact of the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, 2004 to 2014. Alzheimers Dement, 11, 865–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimo A, Winblad B and Jonsson L (2010) The worldwide societal costs of dementia: Estimates for 2009. Alzheimers Dement, 6, 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winblad B, Andreasen N, Minthon L et al. (2012) Safety, tolerability, and antibody response of active Abeta immunotherapy with CAD106 in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, first-in-human study. Lancet Neurol, 11, 597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winderickx J, Delay C, De Vos A, Klinger H, Pellens K, Vanhelmont T, Van Leuven F and Zabrocki P (2008) Protein folding diseases and neurodegeneration: lessons learned from yeast. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1783, 1381–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski T and Goni F (2015) Immunotherapeutic approaches for Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron, 85, 1162–1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan R and Vassar R (2014) Targeting the beta secretase BACE1 for Alzheimer’s disease therapy. Lancet Neurol, 13, 319–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yankner BA, Lu T and Loerch P (2008) The aging brain. Annu Rev Pathol, 3, 41–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahs KR and Ashe KH (2013) beta-Amyloid oligomers in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 5, 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandi PP and Breitner JC (2001) Do NSAIDs prevent Alzheimer’s disease? And, if so, why? The epidemiological evidence. Neurobiol Aging, 22, 811–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Kuo CC, Moghadam SH, Monte L, Campbell SN, Rice KC, Sawchenko PE, Masliah E and Rissman RA (2015) Corticotropin-releasing factor receptor-1 antagonism mitigates beta amyloid pathology and cognitive and synaptic deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Zhang L, Sun A, Jiang H, Qian J and Ge J (2011) Efficacy of statin therapy in chronic systolic cardiac insufficiency: a meta-analysis. European journal of internal medicine, 22, 478–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]