Abstract

We measured the pH-dependent fluorescence decay times of the seminaphthofluoresceins (SNA-FL), seminaphthorhodafluors (SNARF), and BCE-CF using phase-modulation fluorometry. The phase and modulation values were found to be strongly pH-dependent in the physiological pH range, over the easily accessible range of light modulation frequencies from 10 to 300 MHz, making these probes useful as lifetime-based pH sensors. The phase and modulation values are dependent on excitation and emission wavelength as well as pH. This dependence allows the range of pH sensitivity to be chosen by selection of the wavelength(s) and enables increased precision of the pH measurements by use of phase and/or modulationmeasurementsat several wavelengths. These probes can be excited using a a green He-Ne laser at 543 nm, which allows their use in low cost instrumentation. Phase and modulation measurements are especially suitable for sensing applications because they are insensitive to the changes in signal intensity that result from photobleaching, probe washout, and/or light losses.

INTRODUCTION

Optical measurement of pH is an important goal with numerous potential applications in analytical and clinical chemistry.1 At present, most pH sensors and/or optrodes rely on fluorescence detection2–5 due to the need for high sensitivity, particularly with optical fibers. For simplicity, most such measurements rely on the steady-state fluorescence intensity. However, quantitative use of fluoresscence intensities has been difficult due to signal instabilities resulting from probe bleaching, washout, or light losses in the optical fibers or samples. Consequently, there has been interest in developing wavelength-ratiometric methods which are less sensitive to these optical attenuations. Such probes display shifts in their absorption or emission spectra in response to pH, as has been found for pyranine6–9 and fluorescein.10–11 However, relatively few wavelength-ratiometric probes are available, and the known probes require UV or blue wavelength excitation, which precludes their practical use with low-cost laser light sources. To avoid this wavelength limitation, Walt and co-workers12,13 devised optrodes using an energy-transfer mechanism. A pH-dependent intensity change was induced in the long-wavelength probe eosin by a high concentration of the pH-sensitive “acceptor” phenol red.12 While this approach is promising, it suffers from the strong dependence of energy transfer on the acceptor concentration.14 Also, the observed intensity of the fluorophore depends not only on energy transfer but also on the absorbance of the phenol red. In fact, changes in acceptor absorbance, and not energy transfer, may have been responsible for the observed changes in fluorescence intensity of eoein.18 Consequently, such energy-transfer sensors are likely to be sensitive to changes in the acceptor concentration and are not likely to provide calibration-free sensing.

In the present article we characterize the pH-dependent lifetime changes displayed by a series of seminaphthofluoresceins (SNAFL), seminaphthorhodafluors (SNARF), and BCECF (Scheme I) to enable their use as pH lifetime-based sensors. Some of these probes (SNAFLs and SNARFs in Scheme I) were developed by Molecular Probes for we as wavelength-ratiometric pH indicators.15 While one report of their decay times has appeared,16 this report did not consider their use as lifetime-based pH indicators and did not provide the data required for their use as pH lifetime sensors.

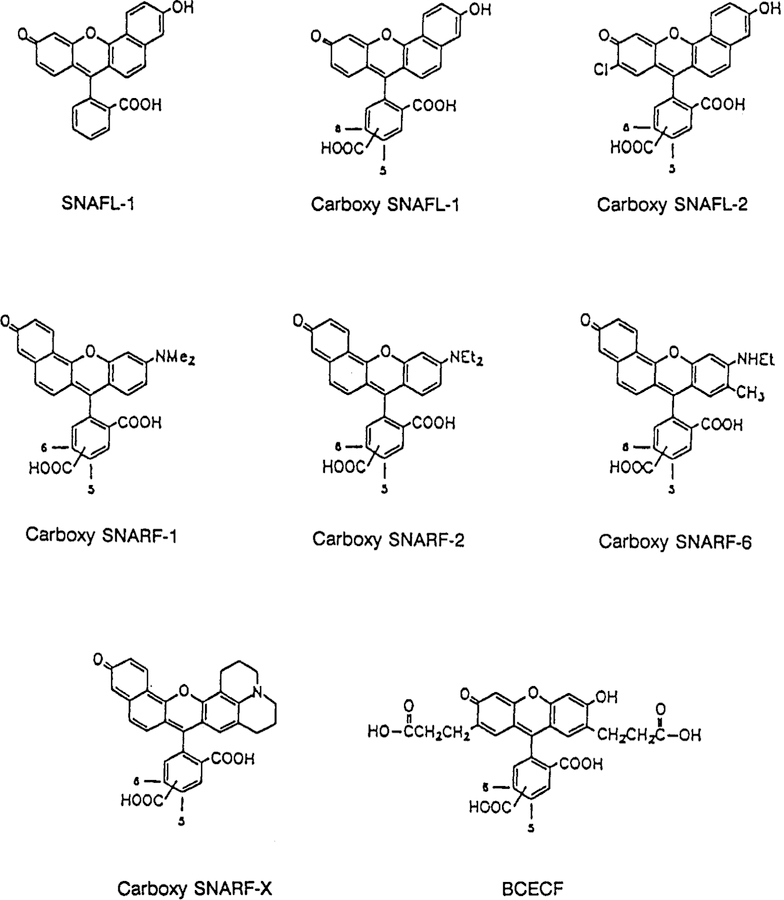

Scheme I. Structures of the SNAFL, SNARF, and BCECF Probesa.

a For a complete listing of the full chemical names, see ref 16.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The SNAFL, SNARF, and BCECF probes were obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR) and used without further purification. The pH-dependent absorption and emission spectra generally agreed with the reported spectra.15,16 Absorption spectra were measured using a Perkin-Elmer Lambda 6 spectrophotometer, and fluorescence measurements were performed using a SLM 8000 spectrofluorometer. Emission spectra were corrected for the spectral characteristics of the apparatus.

Fluorescence lifetime measurements were performed using the frequency-domainmethod, with instrumentation described previously17,18 and a Hamamatau R928 photomultiplier. Magic-angle polarization conditions were used. For measurement of the frequency response of the emission, we used the cavity-dumped output of a ps dye laser, either the fundamental of a R6G dye laser at 563 nm or the frequency-doubled output of a Pyridine 2 dye laser at 360 nm. The dye laser source is convenient because the output is intrinsically modulatad at many frequencies.19,20 The measurements using 643-nm excitation were performed using a 0.4-mW Green He-Ne laser from Melles Griot. The CW output of this laser was modulated with an acoustooptic (AO) modulator from Brimrose, Inc. The modulator was driven at one-half the desired light modulation frequency using the amplified output of a PTS-500 frequency synthesizer. In this mode of operation, we are using the modulator as a standing wave device (Raman-Nath regime). We did not use a carrier frequency as is common in the traveling-wave (Bragg regime) mode of AO modulation.21

The phase angle θ of the emission relative to the excitation is related to the apparent phase lifetime τp by

| (1) |

where ω is the light modulation frequency in radians per second. An apparent lifetime can also be determined from the extent of modulation (m) of the emission relative to that of the excitation

| (2) |

In many cases the fluorescence decay is a multiexponential

| (3) |

where αi are the amplitudes of components with decay times τi. In such cases the values of αi and τi can be determined by nonlinear least-squares fitting, as described previously in detail.22,23 The goodness-of-fit is determined by the value of

| (4) |

where the subscript ω indicates the modulation frequency, the subscript c indicates the calculated value of θ or m for some assumed values of αi and τi, and Δθ and Δm are the uncertainties in the measured values of the phase and modulation, respectively. 22,23 The qualifier “apparent” is used to describe τp and τm, (eqs 1 and 2) because the apparent decay times are equal to the true decay times only for single exponential decays. Otherwise, τp and τm are weighted averages of the components in the decay.24,25

RESULTS

We characterized the pH-dependent lifetimes of most of the available SNAFL and SNARF probes. The usefulness of these probes as pH sensors will be illustrated by a detailed description of one sensor, this being carboxy SNARF-6. More detailed data are available on request and are summarized in Tables I–III.

Table I.

Spectral Properties of pH Indicators in 80 mM Tris, 25°C

| pH indicator | absorptiona |

emissiona |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

λmax (nm) |

λmax (nm) |

||||||

| acid | base | λisob (nm) | acid | base | λisoem (nm) | pKaa | |

| SNAFL-1 | 510 | 539 | 506 | 542 | 616 | 566 | 7.85 |

| C SNAFL-1 | 508 | 540 | 515 | 543 | 623 | 570 | 7.80 |

| C SNAFL-2 | 514 | 547 | 521 | 545 | 623 | 589 | 7.65 |

| C SNARF-1 | 549 | 576 | 534 | 585 | 638 | 598 | 7.50 |

| C SNARF-2 | 552 | 579 | 524 | 583 | 633 | 596 | 7.75 |

| C SNARF-6 | 524 | 557 | 529 | 559 | 635 | 623 | 7.75 |

| C SNARF-X | 570 | 575 | 533 | 600 | 630 | 601 | 7.90 |

| BCECF | 484 | 503 | 473 | 514 | 528 | 521 | 6.92 |

Molecular Probes Catalogue.

Table III.

Phase and Modulation Characteristics of the pH Indicators for Use as Lifetime Sensors

| pH indicator | λexc (nm) | λobs(nm) | fmod (MHz) | Δphase (deg) | Δmod (%) | apparent pKa |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| phase | modul | ||||||

| SNAFL-1 | 543 | >575 | 135 | −10.5 | 22.5 | 7.0 | 6.6 |

| C.SNAFL-1 | 543 | >575 | 135 | −23.0 | 35.0 | 6.1 | 6.5 |

| CSNAFL-2 | 543 | >575 | 135 | −34.5 | 48.0 | 6.3 | 6.7 |

| 560 | −34.0 | 24.0 | 8.5 | 9.0 | |||

| 580 | −36.0 | 44.0 | 7.4 | 8.0 | |||

| 600 | −35.5 | 48.0 | 6.7 | 7.3 | |||

| 620 | −34.0 | 50.0 | 6.3 | 6.7 | |||

| 640 | −34.0 | 49.0 | 6.0 | 6.5 | |||

| 660 | −34.0 | 49.0 | 5.9 | 6.3 | |||

| 563 | 600 | 136.6 | −34.0 | 49.0 | 5.5 | 6.1 | |

| CSNARF-1 | 543 | >575 | 135 | 27.5 | −23.0 | 7.0 | 6.7 |

| C.SNARF-2 | 543 | >575 | 135 | 35.0 | −27.0 | 7.0 | 6.6 |

| CSNARF-6 | 543 | >575 | 135 | −34.0 | 48.5 | 7.2 | 7.5 |

| 560 | −36.0 | 31.5 | 8.4 | 10.5 | |||

| 580 | −34.0 | 44.5 | 8.3 | 9.2 | |||

| 600 | −34.0 | 47.5 | 7.5 | 8.0 | |||

| 620 | −33.0 | 48.0 | 7.1 | 7.5 | |||

| 640 | −33.0 | 48.5 | 6.8 | 7.2 | |||

| 660 | −33.0 | 48.5 | 6.6 | 7.0 | |||

| C.SNARF-X | 543 | >575 | 135 | 12.0 | −16.5 | 7.5 | 7.2 |

| BCECF | 442 | 500 | 65 | 10.0 | −14.0 | 7.6 | 7.7 |

| 540 | 12.0 | −16.0 | 6.6 | 6.9 | |||

The pH-dependent absorption and emission spectra of carboxy SNAFL-6 are shown in Figure 1. As the pH increases, the absorption spectra reveal the progressive appearance of a second species with an absorption maxima near 560 nm and an isobestic point near 530 nm. There are two important features for lifetime-based sensing. First, both species absorb at 543 nm, which is an excitation wavelength that can be obtained from a low-cost laser. Second, the absorption of both species at 543 nm is important for sensing applications because a pH-dependent change in lifetime requires that both forms contribute to the apparent decay time. If one form is nonabsorbing at the excitation wavelength, then the observed emission may be due to just one species and, thus, independent of pH. Also, the relative extent of excitation of each species can be varied by changes in the excitation wavelength.

Figure 1.

pH-dependent absorption and emission spectra of cerboxy SNARF-6. The dashed line (- -) in the lower panel shows the transmission profile of a Corning 2–73 cutoff filter used for some of the measurements.

The pH-dependent emission spectra of carboxy SNARF-6 also reveal two species, with the dominant 559-nm emission at low pH being replaced by a 635-nm emission at high pH (Figure 1, bottom). The presence of emission from two species is essential for lifetime-based sensing. If only one species emits, then the measured lifetime would be that of the emitting species, independent of the pH. The relative contribution of each species to the emission can be altered by selection of the excitation or emission wavelength. As will be seen below, this allows the pH-sensitive range to be altered by changing the wavelengths. Absorption and emission maxima, isobestic and isoemissive wavelengths, and pKa values are summarized in Table I.

The frequency response of the acid and base forms of four SNARF probes are shown in Figure 2. The frequency-responses shift to lower frequencies at high pH (except for carboxy SNARF-6), indicating the lifetime, increases at high pH. This can be seen from multi-exponential analyses (Table III, which shows dominant short- and long-lived species at low and high pH values, respectively.

Figure 2.

Frequency responses of four SNARF probes at low and high pH. The acid and base forms were excited at 563 nm and observed at 600 nm.

The pH-dependent increase in lifetime of the SNARF probes is opposite to that found for the SNAFL probes. The values of lifetime are in good agreement with the results of Whitaker et al.16 The most favorable probes appear to be carboxySNARF-2, carboxySNAFL-2, and carboxySNARF-6 because of the largest change in mean lifetimes.

We note that our assessment of the SNAFL probes as lifetime-based pH sensors is highly dependent on the choice of experimental conditions. This is illustrated in Figure 3 for SNAFL-1 and carboxy SNAFL-1, where the frequency responses were measured with excitation at 563 nm and emission at 600 nm. Under these conditions, the frequency response of SNAFL-1 is nearly independent of pH. The behavior of carboxy SNAFL-1 is more complex, showing either smaller or larger phase angles at high pH depending upon the modulation frequency being below or above 220 MHz, and has no change in phase angle near 220 MHz. This behavior could be a disadvantage if one inadvertently attempts to measure the pH using a frequency where the phase angle changes are close to zero or an advantage if one requires a pH-independent reference. This unusual behavior is the result of selective excitation and/or detection of the high and low pH forms and the heterogeneity of the decays when both forms are excited and detected.

Figure 3.

Frequency response of SNAFL-1 and carboxy SNAFL-1 for 563 excitation and 600 nm emission.

For pH sensing, it is not necessary to measure the entire frequency response of the emission. Measurement of the phase or modulation at a single light modulation frequency is adequate. This point is illustrated in Figure 4, which shows the phase angles at 135 MHz for the four SNARF probes upon excitation with the AO-modulated output of a 543-nm He-Ne laser. This light source was chosen to illustrate the possibility of using an inexpensive light source for the optical pH measurements. Observation of the emission above 575 nm (Corning 2–73 filter), whose transmission profile is shown in Figure 1 (- -), was chosen to observe emission from the short- and long-wavelength forms of carboxy SNARF-6 (Figure 1). However, the long-pass filter provides significantly higher intensity than does the interference filters.

Figure 4.

pH-dependent phase and modulation of four SNARF probes excited with a 543-nm He-Ne laser and 135MHz light modulation.

Phase and modulation data for SNARF probes at 543-nm excitation for a range of pH value are shown in Figure 4. The largest changes are shown by carboxy SNARF-6. As the pH increases from 5 to 9.5, the phase angle of carboxy SNARFS-6 decreases by 34°, and the modulation increases by 48%. These changes are a consequence of the 4.4-fold shorter decay time of the high pH form and its increased contribution to the total signal as the pH increases. The pH-dependent phase and modulation changes of other SNARF probes are in the opposite direction as for carboxy SNARF-6 and smaller in magnitude (Figure 4). These characteristics of the SNAFL, SNARF, and BCFCF probes as lifetime sensors are summarized in Table III. In this table, the sign of the phase angle and modulation changes is in reference to the values at low pH. That is, a negative value of Δθ indicates that phase angles decrease at high pH. A positive Δθ indicates an increase in the phase angle and mean decay time. Similarly, an increase in modulation with increasing pH reflects a decrease in the mean decay time. The differences in phase and modulation shows the range of values which are possible. The apparent phase and modulation pKa values show the useful pH range for various excitation and emission wavelengths. The probe, BCFCF, which is currently the most popular as an intracellular pH indicator (pKa 6.97–6.99), 26 displayed a modest change in phase and modulation. BCFCF cannot be excited with 543-nm He-Ne laser but is convenientlyexcited with 442-nm He-Cd laser.

It should be recognized that fluorescence phase angles are routinely accurate to 0.3°, and often to 0.l°, so that the pH resolution can be 0.02 at the steepst part of the curve using just the phase angle at a single modulation frequency. A phase accuracy of 0.1° would yield pH values which are accurate to 0.006 if using carboxy SNARF-6 as a pH indicator at above experimental conditions. Similarly, the modulation values are typically accurate to 0.006 or 0.5%, so that the pH values calculated from the modulation can also be accurate to 0.02 pH unit.

Examination of Figure 4 reveals that the half-point of the pH-phase angle transition is at a different pH value than that of the modulation. Also, since the phase and modulation signals are processed electronically in a different manner, the reliability and range of the pH measurements can be increased by use of both the phase and modulation values when computing the pH.

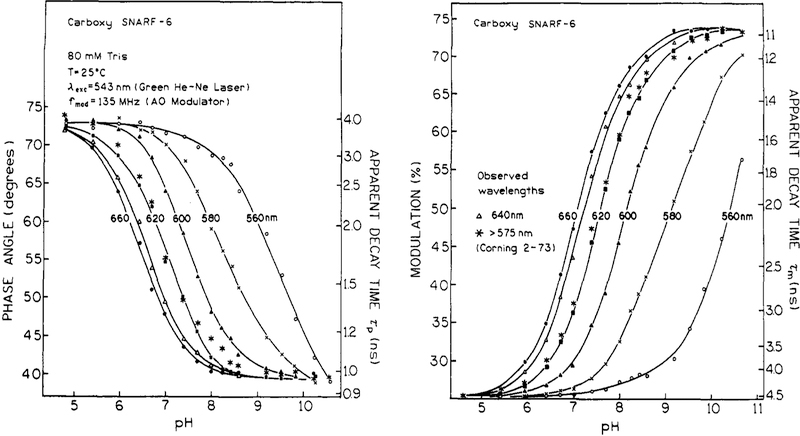

The sensitive pH range of these probes can be dramatically shifted by a technically easy change of the observed emission wavelength. This is shown for both the phase and modulation of carboxy SNARF-6 in Figure 5. The decrease in phase angle occurs at lower pH values for long wavelength (660 nm) observation due to the increased relative contribution of the short-lived (high pH) form at longer wavelengths (Figure 1). Similarly, the phase angles remain large at higher pH values at shorter observation wavelengths near 560 nm due to the predominant emission of the long-lived (low pH) form at this wavelength. Analogous reasoning can be used to understand the wavelength-dependent modulation. The modulation increases faster with pH at long wavelengths because of the increased contribution of the shorter-lived high pH form. The important point is that the pH range and/or accuracy can be expanded or refined as needed by judicious selection of the emission wavelength and/or use of both the phase and modulation data. The pH-sensitive range of carboxy SNARF-6 excited at 543 nm is from 5 to 10.5 (Figure 5). This wide pH range is possible, because of the large wavelength shift between the emission spectra of acid and base forms (). Similar spectral properties for the other SNARF and SNAFL probes are summarized in Table I.

Figure 5.

pH and emission wavelength-dependent phase and modulation of carboxy SNARF-6 with 543-nm excitation.

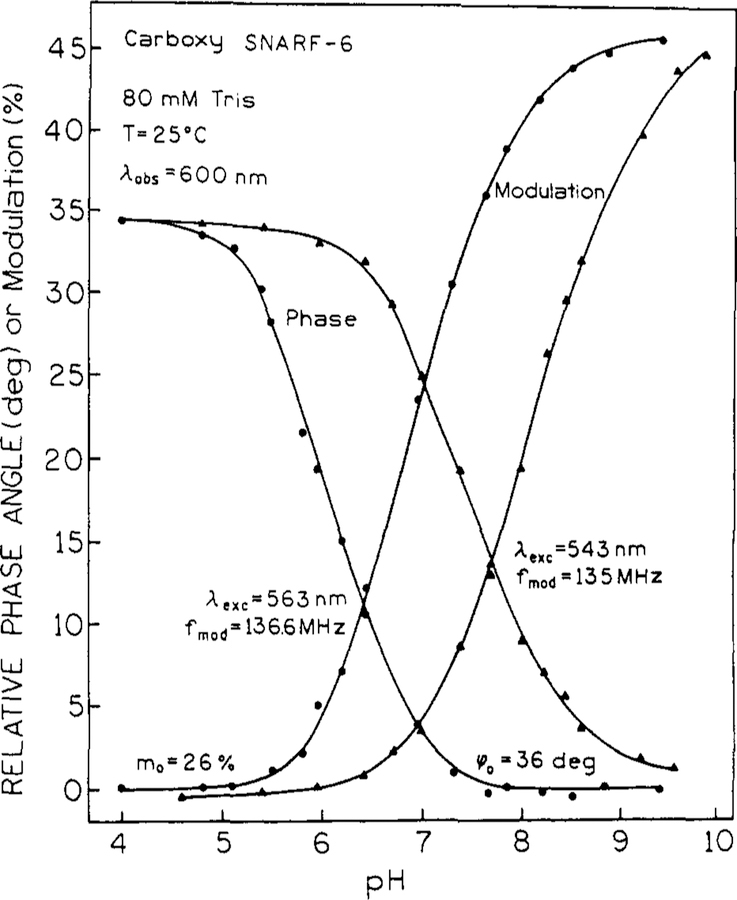

It is important to recognize that the pH calibration curves will depend upon excitation Wavelength. This is illustrated in Figure 6 which compares excitation of carboxy SNARF-6 at 543 and 563 nm. The change is dramatic and reflects the preferential absorption of the high pH (short-lived) form when the wavelength is increased from 543 to 563 nm. Consequently, at a given pH value, the phase angle is smaller and the modulation is higher for excitation at 563 nm aa compared to 543 nm. Fortunately, the wavelength of laser sources is stable, so that this dependence on excitation wavelength will not affect the pH measurements beyond the need to prepare a new calibration curve.

Figure 6.

pH calibration curves of cerboxy SNARF-6 for excitation at 543 and 563 nm.

The other SNARF and SNAFL probes also allow the pH-sensitive range to be adjusted by selection of the excitation and emission wavelengths. The wavelength shifts between the absorption maxima of the acid and base forms of the SNAFL probes are about 30 nm (Table I). Because the absorption spectral shifts are smaller than the emission shifts, and because it is easier to change the detection wavelength than a laser excitation wavelength, it will be easier to adjust the pH-sensitive range by selection of the emission wavelength. In general, for the same excitation and emission wavelengths, the SNARF probes are most sensitive for about 1 unit higher pH values compared to SNAFL probes. The SNARF probes seem somewhat more useful with 543-nm excitation because of the stronger absorption than the SNAFL probes at this wavelength (Table III).

The practicality of using these pH sensors in analytical or especially clinical instrumentation is highly dependent on the stability of the phase and modulation values over time. We tested the stability of this method by measuring the phase and modulation of carboxy SNARF-6 over a period of weeks, using two sets of samples which were stored refrigerated or at room temperature between the measurements. In between these measurements, the phase-modulation instrument was used for a variety of other tasks, with other light sources and detectors. The instrument was reconfigured for periodic measurement of the phase and modulation (Figure 7) at room temperature. The phase and modulation values are obviously stable, and variation between the measurements appears to be due to a lack of constant room temperature. This can be seen by the consistent high or low measurements of all the samples, such as the day-8 phase and modulation values (Figure 7). This stability is a result of the absolute nature and demonstrates the intrinsic reliability of the phase and modulation measurements.

Figure 7.

Time stability of pH sensing by SNARF-6 at room temperature, which varied by several °C. Excitation was at 563 nm, and emission was at 580 nm using an interference filter.

DISCUSSION

An important potential application of optical sensing of pH is the measurement of blood gases, which commonly refers to pH, pCO2, and pO2. The lifetime-based sensors described above allow measurement of these three parameters using a robust and inexpensive 543-nm He-Ne laser light source. The pH measurements can be made as described in this article. Measurement a of pCO2 can be performed using the bicarbonate couple and a CO2-permeable membrane. The availability of these SNAFL and SNARF probes in conjugatable form or bound to dextrans facilitates the construction of the sensor itself.

A blood-gas apparatus also requires an oxygen sensor. Oxygen is a well-known quencher of fluorescence, and oxygen quenching is known to decrease the decay times. However, it is important for the oxygen sensors to have long decay times so that significant quenching occurs at physiological oxygen concentrations. This requirement is satisfied by the tris(phenanthroline)-ruthenium complexes described by Demas and co-workers.27,28 These long-lived oxygen sensors can be excited with a 543-nm He-Ne laser.29 The oxygen sensor is typically embedded in silicon and is not sensitive to pH. If desired, the oxygen sensor could be excited with an inexpensive electroluminescent source.30 Importantly, the short decay times of the SNAFL and SNARF pH probes will not be significantly affected by oxygen, so that there will be little, if any, interference of the pH measurement by oxygen.

The pH-dependent changes in phase and modulation of the SNAFL and SNARF probes also provide opportunities for their use in intracellular chemical imaging. It has recently become possible to measure two-dimensional phase and/or modulation images at frequencies ranging from 1 to 500 MHz.31,32 This apparatus for fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) has been used to image macroscopic objects33 and for microscopic imaging of cells.34 Hence, using FLIM technology, it will be possible to obtain images of intracellular pH distribution in cells and other biological samples. Also, since the SNAFL and SNARF probes also function as wavelength-ratiometric indicators, it will be possible to use FLIM and ratiometric measurements to evaluate the validity of both methods. We note that FLIM provides simultaneous measurements at many sites or pixels, which could be the inputs from a number of fiber-optic sensors, and thereby takes advantage of the fabrication methods proposed by Walt and co-workers.35

Finally, it has recently become possible to measure the phase and modulation of cells on a cell-by-cell basis flow cytometry.36 In flow cytometry it is difficult to use the intensity measurements due to the variability between cells in their size, shape, volume, and extent of probe uptake. The pH-dependent probes described in this report are well-suited for use in flow cytometry because they can be excited with the visible wavelength lines of argon ion lasers which are often used in flow cytometers. Of course, it will be necessary to determine calibration curves for the argon ion laser wavelengths because of the dependence of the calibration curves on excitation wavelength.

In summary, lifetime-based sensing offers many opportunities in analytical chemistry, clinical chemistry, imaging, and flow cytometry.

Table II.

Intensity Decays of the pH Indicators in 80 mM Tris, 25°C, at Low and High DH

| pH indicator | pH | τ1 (ns) | τ2 (ns) | α1 | f1 | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNAFL-1a | 4.9 | 3.71 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 3.71 | 1.5 | |

| 3.75 | 0.71 | 0.975 | 0.995 | 3.74 | 1.2 | ||

| 9.3 | 1.15 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.15 | 19.2 | ||

| 1.21 | 0.18 | 0.839 | 0.972 | 1.19 | 0.8 | ||

| C SNAFL-1a | 4.9 | 3.67 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 3.67 | 2.4 | |

| 9.3 | 1.05 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.05 | 19.4 | ||

| 1.19 | 0.34 | 0.762 | 0.918 | 1.11 | 2.5 | ||

| C SNAFL-2a | 4.9 | 4.59 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 4.59 | 1.5 | |

| 9.3 | 0.93 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.93 | 4.4 | ||

| 0.96 | 0.05 | 0.776 | 0.986 | 0.94 | 2.2 | ||

| C SNARF-lb | 4.9 | 0.48 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.47 | 13.1 | |

| 0.40 | 0.84 | 0.848 | 0.723 | 0.52 | 1.8 | ||

| 9.4 | 1.45 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.45 | 17.5 | ||

| 1.58 | 0.43 | 0.825 | 0.945 | 1.51 | 1.9 | ||

| C SNARF-2b | 4.9 | 0.28 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.28 | 13.5 | |

| 0.35 | 0.01 | 0.101 | 0.820 | 0.31 | 2.0 | ||

| 9.3 | 1.44 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.44 | 59.8 | ||

| 1.63 | 0.01 | 0.101 | 0.952 | 1.55 | 1.6 | ||

| C SNARF-6b | 4.9 | 4.51 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 4.51 | 2.2 | |

| 9.4 | 0.95 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.95 | 54.2 | ||

| 1.16 | 0.34 | 0.617 | 0.846 | 1.03 | 2.1 | ||

| C SNARF-Xb | 4.9 | 1.65 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.65 | 12.9 | |

| 1.39 | 2.69 | 0.810 | 0.688 | 1.79 | 3.3 | ||

| 9.0 | 2.31 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.31 | 29.0 | ||

| 2.64 | 0.80 | 0.773 | 0.918 | 2.59 | 1.1 | ||

| BCECFc | 5.7 | 3.17 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 3.17 | 2.3 | |

| 9.7 | 4.49 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 4.49 | 3.9 |

λexc = 360 nm, λobs = 540 nm (low pH); λexc = 563 nm, λobs = 600 nm (high pH).

λexc = 563 nm, λobs = 600 nm.

λexc = 442 nm, λobs = 540 nm.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by Grant DIR-8710401 from the National Science Foundation and Grants RR07510 and RRO8119 from the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations:

References

- (1).Wolfbeis OS, Ed. Fiber-Optic Chemical Sensors and Biosensors; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 1991; Vols. I and II. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Saari LA; Seitz WR Anal. Chem 1982, 54,823–824. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Offenbacher H; Wolfbeis OS; Furlinger E (1986) Sens. Actuators 1986, 9, 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Wolfbeis OS;Baustert JH J.Heterocycl. Chem 1985, 22, 1215–1218. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Fuh M-RS; Burgess LW; Hirschfeld T; Christian GD Analyst 1987, 112, 1159–1163. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Clement NR; Could JM Biochemistry 1981, 20, 1534–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Zhujun Z; Seitz WR Anal. Chim. Acta 1984, 160, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Wolfbeis OS; Schaffar BPH; Kaschnitz E Analyst 1986,3, 1331–1334. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Wolfbeis OS; Furlinger E; Kroneis H; Marsoner H Fresenius’ Z. Anal. Chem 1983, 314, 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Ohkuma S; Poole B Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 1978, 75, 3327–3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Jordan DM; Walt DR Anal. Chem 1987, 59, 437–439. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Gabor G; Walt DR Anal. Chem 1991, 63,793–796. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Yuan P; Walt DR Macromolecules 1990, 23, 4611–4616. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Bojarski C; Sienicki K Photochemistry and Photophysics; Rabek JF, Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 1990; pp 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Molecular Probes catalogue (1989–1991), pp 86–89.

- (16).Whitaker JE; Haugland RP; Prendergast FG Anal. Biochem 1991, 194, 330–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Gratton E; Limkeman M Biophys. J 1983, 44, 665–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Lakowicz JR; Maliwal BP Biophys. Chem 1985, 21, 61–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Lakowicz JR; Laczko G; Gryczymki I Rev. Sci Instrum 1986, 57,2499–2606. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Laczko G; Lakowicz JR; Gryczynski I; Gryczymki Z; Malak H Rev. Sei. Instrum 1990, 61, 2331–2337. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Wilson J, Hawkes JFB Optoelectronics: An Introduction; Prentice Hall International: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1983; pp 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Lakowicz JR; Laczko G; Cherek H; Gratton E; Limkeman M Biophya. J 1984, 46, 463–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Gratton E; Limkeman M; Lakowicz JR; Maliwel BP; Cherek H; Laako G Biophys. J 1984, 46,479–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Lakowicz JR Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy; Plenum Press: New York, 1983; pp 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Lakowicz JR; Balter A Biophys. Chem 1982, 16, 99–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Tsien RY Annu. Rev. Neurosci 1989, 12, 227–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Bacon JR; Demas JN Anal. Chem 1987, 59, 2780–2785. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Carraway ER; Demas JN; DeGraff BA; Bacon JR Anal. Chem 1991, 63, 337–342. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Lakowicz JR; Szmacinski H, unpublished observation.

- (30).Berndt KW; Lakowicz JR Anal. Biochem 1992, 201, 319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Lakowicz JR; Szmacinski H; Nowaczyk K; Berndt KW; Johnson ML Anal. Biochem 1992, 202, 316–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Lakowicz JR; Szmacinski H; Nowaczyk K; Johnson ML Cell Calcium 1992, 13, 131–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Lakowicz JR; Szmacinski H;Nowaczyk K; Johnson ML Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 1992, 89, 1271–1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Lakowicz JR; Szmacinski H; Nowaczyk K; Lederer WJ; Johnson ML Cell Calcium, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- (35).Walt D; Barnard SM Nature 1991, 353, 338–340. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Pinsky BG; Ladasky JJ; Lakowicz JR; Berndt KW; Hoffman RA Cytornetry 1993, 14, 123–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]